Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

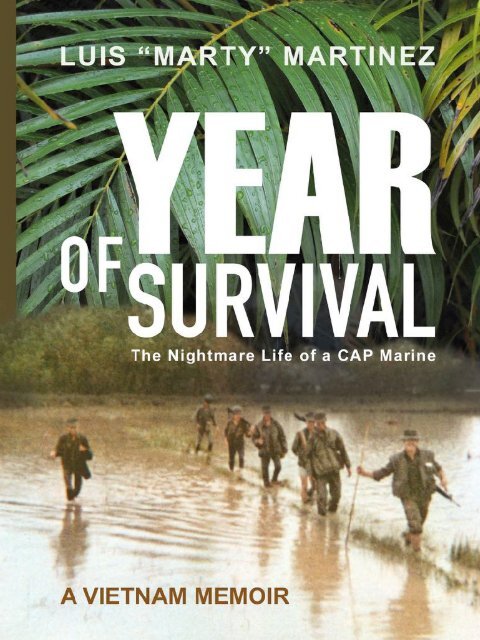

YEAR OF SURVIVAL - INTRODUCTION<br />

I didn’t know what fear and darkness were until I arrived in Vietnam in<br />

1970, and I mean that both literally and figuratively. I was assigned to a<br />

Combined Action Platoon (CAP Unit), which meant living in primitive procommunist<br />

villages and hamlets <strong>of</strong>f the Red Line (Highway #1 was called<br />

the Red Line because that's how it appeared on the map) approximately<br />

20 miles south <strong>of</strong> DaNang, Vietnam. This was a 24/7 survival challenge.<br />

We weren’t sent out into the jungle for missions. We lived in the jungle.<br />

Our mission was to survive. I still remember my first night.<br />

The sheer weight <strong>of</strong> the gear and ammunition I carried was overwhelming;<br />

my legs trembled when I walked. I struggled to keep my balance in the<br />

pitch black <strong>of</strong> night. I worried about being ambushed and not able to<br />

disentangle myself from the straitjacket <strong>of</strong> weapons and gear strapped to<br />

my sweat drenched body. There was a moment when I held my hand up<br />

to flick sweat from my brow, and I could not see it. It was like being<br />

completely blind. There were no lights in the bush. No stars. No<br />

reflection. It was just pitch black darkness, and man let me tell you…” it<br />

was a real bummer.” We knew we were surrounded by the enemy. In<br />

fact, there were VC residing in the villages where we lived. I recall a time<br />

when Doc Coonfield provided the village chief with medical attention for a<br />

laceration on his leg. A couple <strong>of</strong> nights later we ambushed and killed 2<br />

VC. One <strong>of</strong> them was the village chief. He still had the bandages that Doc<br />

wrapped his wound with on his leg. <br />

Within one month in the bush CAP 10 had engaged in several firefights,<br />

had suffered 3 Marines wounded in action (WIA) and 1 killed in action (KIA)<br />

as well as numerous PFs and civilians killed or wounded and we even<br />

exposed an enemy soldier embedded within our ranks. This happened<br />

before my first letter home even got back to Lorain, Ohio. At age 21 I was<br />

struggling with emotions tied to my family’s low-income status, staying in<br />

college and chasing girls. By 22 I was struggling with the emotions tied to<br />

a war I couldn’t run and hide from: losing fellow Marines in my arms,<br />

witnessing charred bodies riddled by shrapnel, killing in order to avoid<br />

being killed myself. <br />

On one occasion, we went on patrol and against tactical basics returned<br />

using the same path because the patrol leader wanted to use a plank the<br />

villagers had laid out as a bridge to cross an irrigation canal. When we

eturned to the canal Gary, BooBoo, and Dakota, who was carrying the<br />

PRIC 25 radio, started across the plank. Little did we know that while we<br />

were out blowing empty bunkers, the VC had hidden a rigged command<br />

detonated 105mm artillery round under the far end <strong>of</strong> the plank. In<br />

addition, they had set a kerosene-soaked command detonated claymore<br />

mine in the bushes on a rice paddy dike in front <strong>of</strong> us. They waited for<br />

Dakota to walk over the 105 round when it was detonated. Frenchy,<br />

carrying the M-79 was about 5 feet behind him so they were able to knock<br />

out our communications and grenade launcher at the same time. I was on<br />

the plank behind Frenchy when the force <strong>of</strong> the detonation catapulted us<br />

skyward and we splashed into the canal. <br />

I panicked when I realized that I had dropped my rifle which I spotted in<br />

the murky bottom <strong>of</strong> the channel. But, each time I tried to reach it I<br />

needed to do an underwater dog paddle in order to stay erect. I had tied<br />

my k-bar knife sheath to my right thigh and as I went into the water<br />

somehow the rope slipped under my knee so that I couldn’t straighten my<br />

leg to stand. Desperate to surface for air I was able to use the knife to cut<br />

the rope and I was able to reach my rifle. I could hear gunfire on the<br />

surface so I stayed underwater as long as I could. Gasping for air, I<br />

surfaced and despite the dinning sound in my ears, I could hear the guys<br />

yelling, “GET FRENCHY! GET FRENCHY!” and pointing behind me. <br />

When I looked back I saw Frenchy floating face down, arms stretched out<br />

as if on a cross and blood saturating the water around his head. The<br />

sensation <strong>of</strong> rushing through the water to save Frenchy was like the inertia<br />

in a slow-moving nightmare as I fought to free each leg from the muck that<br />

sucked at my boots. When I reached his unconscious body I turned him<br />

over and blood squirted from his left upper lip with every heartbeat so I<br />

pinched it tightly. In a half-conscious state, he murmured, “Ah It hurts” so I<br />

let go and was surprised that the bleeding had stopped. I pulled him<br />

toward the edge <strong>of</strong> the canal where Caiado, our dog handler, jumped in.<br />

The react team from our day-haven had arrived by then and they gave us a<br />

hand in lifting him up onto the bank. As I pulled myself out <strong>of</strong> the canal I<br />

saw Dakota leaning against a dike smoking a cigarette as he was being<br />

attended to by Doc Coonfield. Doc Coonfield ran over to give Frenchy first<br />

aid and in the commotion, I could see Gary excitedly talking on the radio<br />

calling for a medevac helicopter. While we waited in a defensive perimeter<br />

Boosinger spotted a kerosene-soaked claymore mine that had been aimed<br />

at us. It had malfunctioned when detonated and broke in half. Had it not

malfunctioned it would have fired 600 steel bearings into our column.<br />

Both men survived and Frenchy was ordered back into the bush a few<br />

weeks later when discharged from the 95th Evacuation Hospital in<br />

DaNang. <br />

I also experienced the heartbreak <strong>of</strong> not being able to save the life <strong>of</strong> a<br />

fellow Marine charred and riddled by the shrapnel <strong>of</strong> a grenade booby trap<br />

in the middle <strong>of</strong> the night. The Russian roulette nature <strong>of</strong> war and the<br />

hatred that motivated revenge instilled a “don’t mean nothin'” devil may<br />

care attitude. Except for Dan Gallagher, the CAP Marines I knew that were<br />

killed in action, Glen Fiester, J.J. Arteaga, Rae Rippetoe, Robert Gaffigan<br />

and Ronnie Ross lost their lives before they could celebrate their 21st<br />

birthday. Rippetoe, Gaffigan and Ross were killed by PFs our “allies.” <br />

Even though some have passed, this book could not have been<br />

undertaken without the support <strong>of</strong> 7th Company members that lived the<br />

nightmare life <strong>of</strong> a CAP Marine and made it back to the world (United<br />

States). They are Paul “Tex” Hernandez, Steve “Booboo” Boosinger,<br />

Michel “Frenchy” Wilson, Bill “Doc” Coonfield, John “Paladin” Shockley,<br />

Greg “Chief” Fragua, Frank Hutson, Juan “Doc” Sanchez, Eddie “Chipper”<br />

Caiado, Jim Wallace, Ed Nunez, Rene Torres, Al Singleton, Mike “Seadog”<br />

Wright, Al “H<strong>of</strong>acker” Ryan, Ernie Soliz, Neil “Bama” Cooper, Mike Burns,<br />

Channing “Blinky” Prothro, Terry Westbrooks, Terry “Stretch”<br />

Straavaldsen, David Stevens, Everett O. Cooper, Prentiss Waltman, William<br />

“Doc” Donoghue, Arthur “Brother Chubby” Yelder, Ken Duncan, Roch<br />

Thornton, Glen Trimble, James “JimRudey” Vollberg, Nathan “Willie” Fulfer,<br />

Mike Harper, Nelson Kilmister, Guy Melton, Dennis “Hucklebuck” Prock,<br />

Scottie Shirley, Al Simmons, and others that are mentioned in this book. <br />

We survived horrors that no human being should ever face, but we made<br />

it. Some <strong>of</strong> us crippled. All <strong>of</strong> us traumatized. So when I say that I came<br />

to know the darkness in Vietnam, I mean complete and utter mental and<br />

physical darkness. I consider this memoir the first ray <strong>of</strong> light to shed light<br />

on those memories. My hope is that it can attest to the insanity <strong>of</strong> war and<br />

honor the heroism <strong>of</strong> the Patriots asked to fight it. All incidents and<br />

accounts are true stories based on my diary and the recollection <strong>of</strong> other<br />

2nd CAG, 7th Company, CAP Marines. The photographs and interactive<br />

media used in this book were either captured personally or by CAP<br />

Marines that have graciously shared them with me.