JAVA Dec '18 issue

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

were retained, which eventually led them to museum<br />

collections.”<br />

Adam Twitchell was drawn to Alaska by the gold rush<br />

in the 1890s. Eventually settling down, he collected<br />

the masks between 1902 and 1912. Married to a<br />

Yup’ik woman named Qeciq, he was able to gather<br />

the masks and observe their use in Napaskiaq, a<br />

village in Alaska.<br />

Twitchell helped collect and preserve the masks,<br />

assisting George Gordon, director of the University<br />

of Pennsylvania Museum of Anthropology, on<br />

a collecting expedition in 1907. Twitchell also<br />

corresponded with scholars, such as anthropologist<br />

Edward Nelson. It was from these connections that<br />

many of the masks on display made their way to<br />

New York and then France. “It was a very exciting<br />

detective story,” Mooney said.<br />

Georges Duthuit, Matisse’s son-in-law, was in<br />

New York City when World War II erupted in 1939.<br />

Stranded with other expatriate European artists and<br />

intellectuals, they explored vast U.S. collections of<br />

Native American art and acquired their own artifacts<br />

when possible, including several pieces featured in<br />

32 <strong>JAVA</strong><br />

MAGAZINE<br />

the Heard show – some of which have returned to<br />

the United States for the first time since 1945.<br />

When Duthuit was able to go home following the<br />

armistice, he had about a dozen Yup’ik masks with<br />

him. Duthuit’s wife, Marguerite, asked her father<br />

to contribute drawings to a book inspired by the<br />

artifacts that her husband was publishing, titled<br />

Une fête en cimmérie. Matisse used photographs<br />

of indigenous people from northern latitudes as his<br />

models for the drawings.<br />

Though Matisse did not sketch or copy the masks<br />

directly, he drew inspiration from their simple yet<br />

elegant lines. He analyzed their visual vocabulary,<br />

recognizing the makers as kindred spirits in the<br />

quest to distill the essence of a person’s spirit<br />

and personality. The influence bled into Matisse’s<br />

subconscious and back out into his art. He began<br />

calling his portraits “masks.”<br />

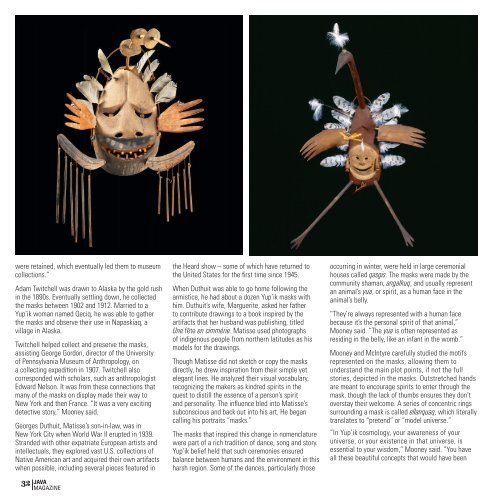

The masks that inspired this change in nomenclature<br />

were part of a rich tradition of dance, song and story.<br />

Yup’ik belief held that such ceremonies ensured<br />

balance between humans and the environment in this<br />

harsh region. Some of the dances, particularly those<br />

occurring in winter, were held in large ceremonial<br />

houses called qasgis. The masks were made by the<br />

community shaman, angalkuq, and usually represent<br />

an animal’s yua, or spirit, as a human face in the<br />

animal’s belly.<br />

“They’re always represented with a human face<br />

because it’s the personal spirit of that animal,”<br />

Mooney said. “The yua is often represented as<br />

residing in the belly, like an infant in the womb.”<br />

Mooney and McIntyre carefully studied the motifs<br />

represented on the masks, allowing them to<br />

understand the main plot points, if not the full<br />

stories, depicted in the masks. Outstretched hands<br />

are meant to encourage spirits to enter through the<br />

mask, though the lack of thumbs ensures they don’t<br />

overstay their welcome. A series of concentric rings<br />

surrounding a mask is called ellanquaq, which literally<br />

translates to “pretend” or “model universe.”<br />

“In Yup’ik cosmology, your awareness of your<br />

universe, or your existence in that universe, is<br />

essential to your wisdom,” Mooney said. “You have<br />

all these beautiful concepts that would have been