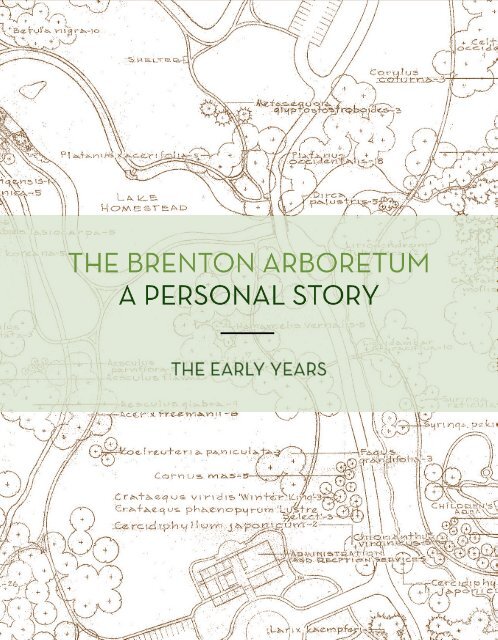

The Brenton Arboretum: A Personal Story

Buz Brenton's memoir of the early years of The Brenton Arboretum in Dallas County, Iowa.

Buz Brenton's memoir of the early years of The Brenton Arboretum in Dallas County, Iowa.

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

1

2<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Brenton</strong> <strong>Arboretum</strong>, view from the northwest towards the Vista<br />

Room.

3

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Brenton</strong> <strong>Arboretum</strong> aerial view captured by drone November 2017.<br />

4

5

6

View to the west from the cottonwood (Populus deltoides) collection.<br />

7

8

I feel a need to briefly describe the evolutionary<br />

process involved in bringing about a public<br />

institution — in this case an arboretum — if ever so<br />

humble. It would never have happened without the<br />

encouragement and guidance of my wife, Sue.<br />

As I think back over my life, I value this experience most highly, for it has<br />

given me an opportunity to learn, grow, be of service and use, and (selfishly) be<br />

able to spend my days doing what I like best: being out of doors with my dog,<br />

walking the land, and helping out with the work. <strong>The</strong>re is no other activity I can<br />

think of which gives me such satisfaction daily, year round.<br />

<strong>The</strong> seasons energize me. Being in the elements both soothes and<br />

sensitizes me. <strong>The</strong> sense of what is going on out there has given me a second,<br />

very real life right along with my more conventional life. I have lived in two<br />

worlds, separate but joined, dependent on each other. Boredom, which has<br />

always been a shadow in the corner for me, has been pretty well kept at bay.<br />

But the real value here is what this arboretum can do for others. It is<br />

nothing without this. That lives on.<br />

From time to time I receive comments from visitors about having more<br />

features or attractions or things to do. This, I remind myself, is not that sort of a<br />

place to any great extent, not up to now anyway. This is a place for being outside<br />

with majestic growing life all around and the opportunity to contemplate the<br />

symbiotic relationship between man and nature, without which man often<br />

stumbles and loses his way. This is probably more true for all of us as we become<br />

increasingly urbanized.<br />

Perhaps we have aided these processes a bit here at the <strong>Brenton</strong><br />

<strong>Arboretum</strong>. I have been very fortunate!<br />

Sue and Buz <strong>Brenton</strong> at the <strong>Arboretum</strong>, June 2016.<br />

9

10

I should make one thing clear before we begin. Growing up, I had little interest in trees or the<br />

outdoors. This was even true into my thirties. At summer camp, I avoided the nature study field<br />

trips, which took us into the woods. My interest was athletics. But later on, the woods did have an<br />

appeal as a place to meet friends, smoke, and even drink beer. What a start!<br />

One day at a Saturday afternoon movie matinee I saw a short documentary about Florida’s<br />

Cypress Gardens 1 . I was drawn to it. I was perhaps twelve. It was marvelous to see the way two<br />

people with a shared vision could create a recreation area out of wetlands. <strong>The</strong> tandem waterskiing<br />

was fascinating. People were drawn there. Somehow, even at a young age, this had appeal to me.<br />

Time went on. I grew and went away to college. In 1960, my wife Sue and I moved back to<br />

Des Moines and then to Dallas Center, Iowa after a three-year stint in the Intelligence Corps of the<br />

United States Army, a good portion of which we spent in Korea. Our son, Kenneth, was not quite<br />

two years old. My older brother, Bob <strong>Brenton</strong>, was running our family farms in Dallas County,<br />

Iowa, which was about 30 minutes from Des Moines. <strong>Brenton</strong> Brothers Farms, as it was known,<br />

had been in our family since 1853. It started with my great grandfather, William H. <strong>Brenton</strong>, and<br />

continued with my grandfather Charles <strong>Brenton</strong>, my father W. Harold <strong>Brenton</strong>, my brother Bob,<br />

and my nephew Bill <strong>Brenton</strong>. Like several of my siblings, my first job was working on the farm for<br />

Bob. One day we were out walking the wetlands and marshes at our Ingersoll farm, which is<br />

northeast of Dallas County 2 . Walking this wetland forest area reminded me of what Cypress<br />

Gardens must have looked like before development. Bob thought I was a bit crazy when I<br />

suggested that some day maybe we could develop this area as a public space, with waterways, grass<br />

areas, and amenities for visitors. Just where all of this interest in wetlands and green spaces had<br />

come from, I don’t know. But I do know it was a beginning.<br />

In 1963, my father, Harold, was president of our family’s other growing business, <strong>Brenton</strong><br />

Banks, Inc. Dad asked me to consider leaving Des Moines to move to Davenport, Iowa, where we<br />

were organizing a new bank, the First National Bank of Davenport. Dean Duben, who had been the<br />

head of our South Des Moines National Bank for several years, was in charge. I liked being with<br />

Dean and learned a lot from him. Our family lived in Davenport for about six years until the latter<br />

part of 1969 when Dad died that September from a heart attack. He was 69 years old. Bob wanted<br />

me to return to the Des Moines area to help him and brother, Bill, manage the banks 3 .<br />

Sue’s parents also lived in Des Moines, so it made sense for us to move back to our<br />

hometown with our three children, Kenneth, Lockie, and Julie. It was Christmas 1969. It was the<br />

right thing to do, but in truth, I was a little disappointed. Our family liked Davenport and its<br />

Sugar maple (Acer saccharum) in autumn.<br />

11

location along the Mississippi River. It was a wonderful place to both work and live. While there, I<br />

had formed a habit of going out along the great Mississippi River to tromp and look around with<br />

my regal Labrador dog, Chaser, and any of the kids who would come along. This was a Sunday<br />

afternoon activity. Sue also came along occasionally. Now I found myself in Des Moines without<br />

much to do on weekends. Often Sue and I did take our children to our Dallas County farm on<br />

Sunday and walk back in the woods and sloughs on the before mentioned Ingersoll Farm, but<br />

somehow I wanted to be out more.<br />

Many of us can look back at our lives and identify a significant moment that points us, often<br />

unwittingly, in a new direction. That was the case when my sister, Jane Eddy, now deceased, gave<br />

me a marvelous tree identification book, <strong>The</strong> Book of Trees, by William Grimm. It included very<br />

skillful and precise drawings of leaves, twigs, fruit, and flowers related to nearly every commonly<br />

known Eastern North American tree. <strong>The</strong> book had a wonderful key that outlined various tree<br />

characteristics, and helped me begin the process of identifying all that was around me both in<br />

summer and winter.<br />

This was exciting. I really started to differentiate between the species and for the first time<br />

began noticing their manifold characteristics and differences that separated one tree from another:<br />

the bark, the twig, the leaf, the structure, the size. It was fascinating. I was learning the common<br />

names of the native trees. I gained confidence. I wanted to know more. I took a semester course at<br />

Drake University focused on woody plant identification. As I proceeded to learn more about each<br />

12

species, they became acquaintances, friends. <strong>The</strong>re they were, and I was often with them. Always<br />

silent but so alive! <strong>The</strong>y were both majestic and modest, but sometimes exuberant, always attached<br />

to place. I admired their character, their permanency.<br />

One day, walking through the countryside with <strong>The</strong> Book of Trees, I began to notice all of<br />

the bottles and cans that littered the land. It bothered me. Soon after, I came across a Boston<br />

Federal Reserve analysis of a recent bottle bill 4 passed by the Massachusetts legislature. Contrary<br />

to what bottlers and grocery store owners were saying, the report indicated that giving people an<br />

incentive to recycle their bottles and cans was actually a boon for the economy and the<br />

environment.<br />

At about this time, the state of Iowa was starting an initiative called Iowa 2000 5 . Governor<br />

Robert D. Ray and University of Iowa President Willard “Sandy” Boyd led the initiative to look at<br />

the future of Iowa's economics, resources, and society. <strong>The</strong> governor asked me to get involved. <strong>The</strong><br />

more I thought about the bottle bill, the more I was convinced this was something that could make a<br />

difference in Iowa. I took the idea to the governor and told him that, in my opinion, if he wanted to<br />

do something significant under Iowa 2000, he should consider getting rid of the litter from bottles<br />

and cans. I handed him the study by the Federal Reserve and told him he might find it interesting. I<br />

was pleasantly surprised when he included the bottle bill as part of his legislative agenda and made<br />

it a priority to get it passed into law.<br />

This was an exciting thing to be part of. And through this process, I was learning there were<br />

others like me who cared deeply about the land. People in the Sierra Club, my first environmental<br />

organization, taught me the ecological importance of trees and forests. I learned from their<br />

publications and also those of the National Arbor Day Foundation and the Audubon Society. This<br />

was a whole new world to me. It all fit so well together: soil, moisture, air, woody plants, all<br />

connected and influencing one another, and needing one another for healthy existence. My appetite<br />

to learn more continued to build. Here I was, a banker by day but taking a course in cellular biology<br />

at Des Moines Area Community College. <strong>The</strong> class helped me understand the processes of<br />

photosynthesis and respiration.<br />

This knowledge and these feelings about trees slowly grew. I was now doing a lot of<br />

reading about the natural world and environmentalism and became concerned for the health of our<br />

planet. Walking, looking, and identifying strengthened all of this early knowledge and these early<br />

feelings. I wanted to do something, but what? It was the early 1990s. I told my brothers, Bill and<br />

Bob, that I wanted to retire from the day-to-day business of banking in order to devote more of my<br />

time to other matters. I was 58 years old and my energy was abundant. Things were starting to<br />

come together in my mind.<br />

I had read earlier about a man in Missouri who bought woodlands, lots of woodlands, just in<br />

order to preserve them. This affected me, but as I thought about it, I realized that his scope was<br />

beyond my resources. However, I began to think that I could buy some land somewhere. I started to<br />

13

look around central Iowa. I wanted land to plant the trees I had come to know in my wonderings:<br />

native trees.<br />

I came close to bidding on an 80-acre piece of scrub farmland south of Indianola, Iowa. I<br />

also talked to the head of the Warren County Conservation Board, which had just established a<br />

nature center on considerable land there. This was less than 30 minutes from my home, and I<br />

thought I could possibly use this land, but in the end I decided against it.<br />

About this time, in 1993, Bob and I decided to divide our farmland into two separate<br />

corporations: one for his family and one for mine. This was all very amicable. Given Bob’s<br />

background, his family was interested in farmland as a business. This was our common family<br />

history. But my family wished to own farmland as an investment and not operate it. And so we<br />

divided: his as <strong>Brenton</strong> Brothers, the historic name, and ours, as <strong>Brenton</strong> Farms.<br />

Part of <strong>Brenton</strong> Farms is a 200-acre parcel located about 1.5 miles southwest of Dallas<br />

Center on what had historically been called our family’s Home Farm. This was ancestral land and<br />

close to where our family first settled in 1853. It was the area where the family wagon, coming<br />

from Indiana, came to rest and where the first rude cabin was built. <strong>The</strong> exact area can be seen from<br />

the present <strong>Brenton</strong> <strong>Arboretum</strong>, located in a grove of black locust a quarter mile south of the<br />

arboretum.<br />

I was only slightly familiar with this land and had never considered it for tree planting. I<br />

thought I would buy land elsewhere. However, my wife, Sue, who guided me in many matters,<br />

suggested that I give it serious consideration as a tree-planting site, particularly the non-crop part<br />

that had been used for grazing. She was eager to see me proceed. Without her enthusiasm, all of<br />

this never would have happened.<br />

It was winter of 1995. <strong>The</strong> snow was deep. I drove onto the land and immediately got stuck<br />

in a low area. Neighbor Dave Burkett, whose family had been farming this land for a long time,<br />

took mercy on me and pulled me out. This land had topography. It formed a natural bowl. Much of<br />

it was not suitable for row crops. It was pasture. It was open. It had two streams running through it,<br />

one old but very sturdy cement bridge and an old, but deep farm pond. My mind was racing. Could<br />

this be the place? I needed to spend time walking and thinking.<br />

1. Cypress Gardens was a botanical garden and theme park near Winter Haven, Florida open from 1936 to 2009,<br />

planted by Dick Pope Sr. and his wife, Julie. It was billed as Florida's first commercial tourist theme park.<br />

2. <strong>The</strong> land that now forms Dallas County, and our family property, was ceded by the Sac and Fox nation to the<br />

United States in a treaty signed on October 11, 1842. <strong>The</strong> <strong>Brenton</strong> family acquired the land in 1853.<br />

3. In 2001, <strong>Brenton</strong> Banks was sold to Wells Fargo. At the time of the sale, it was the largest Iowa-based bank<br />

holding company.<br />

4. Under the bottle bill, beverage retailers assessed a deposit fee on consumers, typically a nickel. That deposit was<br />

then refunded when the beverage container was returned to a retailer.<br />

5. Iowa 2000 was a series of planning conferences proposed by then-U.S. Representative John C. Culver in 1972.<br />

14

Aerial and satellite<br />

photos of <strong>Brenton</strong><br />

farmland September<br />

1996 and October 2017.<br />

15

16

After becoming quite familiar with the more or less 120 acres of non-crop land that my family<br />

owned, I decided it was almost perfect. This was the place: close to Des Moines, in the path of<br />

westward development, and with topography and water, little clearing needed, good soils, and<br />

historic family value.<br />

It did have a couple of negatives. A stream with no bridge almost equally bisected the land.<br />

A nephew, Charlie Brandt, owned 40 of the 120 acres. <strong>The</strong>se issues could be overcome. <strong>The</strong> more<br />

pressing problem was the matter of trying to figure out specifically what I wanted to do. My ideas<br />

were not well formed.<br />

I first thought I would concentrate on several dozen native species and plants each in<br />

differing designed groupings. If well done, this could lead to artistic displays that people could<br />

walk through, enjoy, and learn from. I liked this idea very much and still do. I would call it a “tree<br />

garden.” But I needed to talk to people who knew something about arboreta and planting trees. I<br />

needed guidance.<br />

Bob and Ann Fleming lived about 20 minutes south of Des Moines in Norwalk, Iowa, on an<br />

acreage named Danamere Farm. Ann, a member of the well-known Wallace family 6 of Des<br />

Moines, had started a nursery business specializing in trees she loved. Gardening and agriculture<br />

were in her blood. Ann was a landscape designer who propagated, grew, and sold shade trees and<br />

ornamental shrubs. Her particular interest was to introduce unusual or under-represented plants to<br />

Iowa gardens. Her husband, Bob, was a very capable businessman and a tree man, and I knew him<br />

well. <strong>The</strong>y would give me honest advice.<br />

I called them on September 27, 1996. I told them I wanted to plant trees in some fashion for<br />

public enjoyment on a piece of <strong>Brenton</strong> land. <strong>The</strong>y were enthusiastic. This meant so much. <strong>The</strong>y<br />

encouraged me to seek species of a hardy nature and go for it. I was thrilled.<br />

<strong>The</strong>y had other good advice. <strong>The</strong>y directed me to the Morton <strong>Arboretum</strong> in Lisle, Illinois,<br />

which covers 1,700 acres and is made up of mostly woody plants of various types and extensive<br />

collections of trees. It includes native woodlands and a restored Illinois prairie. <strong>The</strong>y also sent me<br />

to Iowa State University’s Landscape Architecture Department and to Bob Rennebohm, a noted<br />

nurseryman in Des Moines who later became a board member of <strong>The</strong> <strong>Brenton</strong> <strong>Arboretum</strong>. <strong>The</strong>y<br />

also encouraged me to visit other arboreta as much as possible, starting with the Iowa <strong>Arboretum</strong><br />

near Boone, Iowa. <strong>The</strong> 378-acre arboretum was then about 30 years old and displayed many species<br />

of trees, shrubs, and flowers. Somewhere in the past I also remembered reading a Des Moines<br />

Bluebird house in the prairie with black-eyed Susan (Rudbeckia hirta).<br />

17

Register article about the Bickelhaupt <strong>Arboretum</strong> in Clinton, Iowa, which had opened in 1970.<br />

Neither Bob Bickelhaupt, who had been a successful car dealer in Clinton, nor Frances 7 , his wife,<br />

had any formal training in horticulture. As Frances told <strong>The</strong> Iowan magazine in 1982: “How this<br />

man who once decorated his indoor swimming pool with $200 in artificial plants became the<br />

zealous owner of an arboretum is a story that begins with walking.” It turns out the Bickelhaupts<br />

walked more than 90 miles in their hometown of Clinton to muse over and map the city trees,<br />

which were being destroyed by Dutch elm disease. As a result of the walks, they concluded that the<br />

devastation of the Dutch elm disease and the apparent lack of knowledge about landscaping made<br />

an educational arboretum a worthwhile goal.<br />

<strong>The</strong>ir story and their path struck me as a most worthy model for lives well spent. It<br />

energized me, and they became very important mentors. Bob and Fran were in their early 70s when<br />

I made my first visit to their arboretum. It struck me that they were very fit for their age. <strong>The</strong>y had a<br />

swimming pool in their home, and it was clear they used it. <strong>The</strong>ir home sat on the grounds of the 14<br />

-acre arboretum, which was by then well established. It struck me as a beautiful, hilly place filled<br />

with trees, shrubs and herbaceous plants all mixed in a most artistic, restful and satisfying manner.<br />

A lovely small stream ran through it.<br />

Bickelhaupt <strong>Arboretum</strong> in<br />

Clinton, IA surrounds the<br />

home where Bob and Fran<br />

Bickelhaupt lived.<br />

Bob and Fran gave me all the time in the world to ask questions and offered much<br />

encouragement and valuable advice. <strong>The</strong>y explained the practical aspects of establishing and<br />

maintaining a public arboretum under the IRS rule governing private operating foundations. This<br />

meant that, while declared for public use, the majority of their monetary support came from one<br />

source: the Bickelhaupts. <strong>The</strong>se outlays could be deductible for income tax purposes. <strong>The</strong>ir<br />

foundation was governed by a board of trustees and managed, with good horticulture help, by Fran<br />

and Bob. <strong>The</strong>y were kind enough to open all of their arboretum financial records to me.<br />

18

I told them about my idea of taking a piece of land, now identified as 120 acres of the Home<br />

Farm, and planting various groupings of single species of native trees in an artistic design. I also<br />

told them my thoughts about creating a place where people could learn about the natural world<br />

through a better understanding of trees. I felt that if each tree group, containing only one species,<br />

were set off separate and distinct from other groups, it would increase the awareness and<br />

understanding of that species. <strong>The</strong> visitor would therefore—so my theory went—be more likely to<br />

come away remembering the salient qualities of that species of tree. He/she would have new,<br />

specific knowledge of a type of tree and might identify with it and know something about it. <strong>The</strong><br />

visitor most likely would appreciate its distinctiveness and importance when they knew it<br />

personally.<br />

A grouping of several pin oaks (Quercus palustris) at <strong>The</strong> <strong>Brenton</strong> <strong>Arboretum</strong> helps impress upon guests their distinct<br />

habit and characteristics.<br />

It seemed to me that if one couldn’t identify an object, it was not known and therefore it was<br />

not so important. But it is human nature to assign an object—tree or anything—a higher value if<br />

one is familiar with it and enjoying it. And, if the known object is threatened, a person will feel an<br />

anxiety about its possible loss or injury and be more likely to speak out or act, or at the very least,<br />

feel a significant loss. This fueled my vision to create a tree garden where visitors could get to<br />

know and understand each group, each species. My great hope was that the experience would<br />

prompt visitors to advocate for the natural world of trees and learn more about the importance of<br />

trees to our global health and wellbeing.<br />

19

This was my rudimentary theory.<br />

This was my goal: to establish these<br />

groupings in some sort of a tree garden. I<br />

explained much of this to the<br />

Bickelhaupts. <strong>The</strong>y enthusiastically<br />

endorsed my stance. Although their<br />

underlying philosophy for creating their<br />

arboretum may have been different than<br />

mine, they understood and told me to do<br />

it: create my vision.<br />

But they also offered me some<br />

strong advice, which I heeded. Internal<br />

Revenue Service clearance was needed to<br />

move forward. This had been a lengthy<br />

and expensive process for Bob and Fran,<br />

who paid accountants and lawyers. <strong>The</strong>y<br />

gave me their two-inch-thick file to use as<br />

a model. Fortunately, by now, the 1990s,<br />

the process of getting a 501(c)(3)<br />

clearance had been simplified. Dave<br />

Midtlyng, my accountant, saw no<br />

problems as long as the proposed arboretum<br />

was open to the public on a regular basis. This was really the main test for clearance and resultant<br />

tax deductibility when it came to contributions to the new organization.<br />

This image is a close-up of the grid system established to<br />

position and record tree locations throughout the arboretum.<br />

Fran and Bob also strongly encouraged me to hire a landscape architect to create a master<br />

plan before I turned the first shovel of dirt. I had made contact with others, but they suggested<br />

Anthony “Tony” Tyznik of the Morton <strong>Arboretum</strong>. This became a profoundly important referral.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Bickelhaupts were also emphatic that I understand the watering needs of young plants.<br />

Bob’s rule was to water all trees that had been in the ground for two years or less with one gallon of<br />

water per foot of height on any given week in which rainfall was less than one inch. This was<br />

maintained until the soil froze. Although we learned to modify this fine rule, depending on the<br />

species and other conditions, it also has become our regime.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Bickelhaupts next encouraged me to create a land grid system that would make it easier<br />

for staff and visitors to find plantings in the field. <strong>The</strong>n they told me to visit other arboreta to gather<br />

ideas. Through all of this, I was learning what an arboretum was. My initial idea of a tree garden<br />

featuring a series of native species, separately arranged in individual, distinct groupings, was<br />

evolving into a broader concept. I now was envisioning an arboretum with an expanded palate of<br />

trees and shrubs, including some non-natives. I wanted to plant what would grow, but retain the<br />

20

idea of individual clusters of similar types.<br />

Throughout this period, I talked to and learned from a number of people, including Peter<br />

van der Linden, the original director of the Iowa <strong>Arboretum</strong> who became a <strong>Brenton</strong> <strong>Arboretum</strong><br />

board member. <strong>The</strong> Iowa State Horticultural Society organized the 378-acre Iowa <strong>Arboretum</strong> in<br />

Madrid, Iowa, in 1966. Thirty years later, when Peter and I first spoke, he was plant curator of the<br />

Morton <strong>Arboretum</strong>. He and Dr. Don Farrar of Iowa State University had co-authored the book<br />

Forest and Shade Trees of Iowa. I read it, was influenced by it, and was excited to talk with him.<br />

Peter introduced me to Tony Tyznik, who had been so important to the Morton <strong>Arboretum</strong>.<br />

After more than three decades there, Tony had recently retired as the resident landscape architect.<br />

At that time, what you saw at the Morton <strong>Arboretum</strong> was largely his design. I had been warned that<br />

he was cautious and discreet and disliked modern communication, including the phone! When I met<br />

Tony in early November 1996, his wife had just passed away and he was working part-time for his<br />

son, David, who owned a nursery business 30 miles west of Chicago. I told Tony, who held a<br />

landscape architecture degree from the University of Wisconsin, about my property and vision. In a<br />

very soft, cautious voice he said he would consider coming over and would call back. Luckily, he<br />

did call back and said he would visit the property that same month.<br />

During this time, Peter was also sensitizing me to the need to keep records certifying the<br />

origin and condition of what we planted. If I wanted <strong>The</strong> <strong>Brenton</strong> <strong>Arboretum</strong> to have a scientific<br />

basis, we had to know the provenance of our trees. Kathie Bonislawski of the American Public<br />

Gardens Association (formerly the American Association of Botanical Gardens and Arboreta) later<br />

repeated this thought. She helped me understand the differences between a botanical garden (more<br />

herbaceous plantings) and arboreta (more woody material). She also reinforced the absolute<br />

View of the <strong>Arboretum</strong><br />

before the planting began.<br />

21

necessity of keeping thorough research records of all plantings, including origin, condition, and a<br />

continuous update of status after planting. Only with this background information would the<br />

arboretum be able to enter the world of scientific study.<br />

I liked the idea of scientific study for our plants. Such study, I somehow felt, would be<br />

useful to the scientific community, help set us apart, and lead to the public benefit of understanding<br />

the characteristics of tree types grown in central Iowa.<br />

Many people offered other insights. David Dahlquist, a Des Moines landscape designer,<br />

explained to me that a certain tree—no matter what species—would only thrive if it were properly<br />

sited with the correct soil, protection, sun, wind, etc. Remarkably, this was a new idea to me. He<br />

also suggested that if I bought very small trees, they might best be started in a protective nursery<br />

before being planted in the open. This thought began a debate in my mind over the numerous pros<br />

and cons of planting small trees, those an inch or two in diameter, as opposed to larger stock.<br />

Pam Nagel, an acquaintance of many years at Miller Nursery in Johnston, Iowa, prompted<br />

me to look beyond Des Moines for tree sources. She believed that my arboretum site was high,<br />

unprotected, and mostly exposed, thus narrowing the range of species that would do well there.<br />

Later we discussed how to plant trees, hole sizes, watering needs, staking, and mulching. It became<br />

apparent that in order to water, I was going to need a large water tank, a wagon to set the tank on,<br />

and a truck or tractor to pull the water wagon. I hired Pam to advise and help me with all of these<br />

matters.<br />

During the last three months of 1996, I<br />

spoke with an assortment of people, all of whom<br />

furthered my knowledge, gave me ideas, and<br />

offered services: Tom Dunbar, a Des Moines area<br />

landscape architect, provided thoughts on master<br />

planning. Dale Inglett, a tree nursery specialist<br />

from Ames, Iowa, visited my site and was the first<br />

person to suggest staking each of our small trees<br />

during planting. Dwight Hughes had a successful<br />

tree nursery in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, and was<br />

founder and board member of the Iowa <strong>Arboretum</strong>.<br />

We discussed having him provide native and nonnative<br />

trees and supervise their planting but<br />

ultimately agreed distance made it too impractical.<br />

Mark Ackelson, head of the Iowa Natural<br />

Heritage Foundation, referred me to Dr. Herbert<br />

Kersten of Fort Dodge, Iowa. Kersten had planted<br />

thousands of walnut trees from collected seeds and<br />

cuttings for more than 20 years on his 200-acre tree<br />

To this day, newly planted trees are typically<br />

staked. <strong>The</strong>y are also caged to prevent damage<br />

from deer and rabbits.<br />

22

farm west of the city. While not directly able to help me, his vast knowledge of selection and<br />

variability within a species was eye opening. He gave me the idea to conduct observational<br />

research, a concept we later initiated that has become so important to us.<br />

I also talked with Jeff Rousch, a nationally known landscape architect. He quoted me a price<br />

for visiting the arboretum to provide his initial thoughts. I didn’t think I had the budget to do it, but<br />

looking back, his proposal was very reasonable. He had a lot of experience with master planning<br />

that could have been valuable.<br />

Mown trail through the elm (Ulmus sp.) collection.<br />

6. Ann was the great-granddaughter of Henry ("Uncle Henry") Wallace and Nancy Cantwell Wallace, founders and<br />

editors of the agricultural journal, Wallace's Farmer. Her family, along with other Iowans, founded Pioneer Hi-<br />

Bred Seed Corn Company.<br />

7. In 1999, well into the third decade of the creation of their public garden, Frances Bickelhaupt wrote a book, A<br />

Private Couple Creates a Public Garden, to document the challenges and successes of this environmental project<br />

she and her husband undertook in their retirement. She died July 27, 2013.<br />

23

24

Thanks to the Bickelhaupts and many others, I finally had a model for creating an arboretum.<br />

Now I needed to act. I still had a lot to do if I wanted to plant in 1997. It was fall 1996, and I<br />

needed a master plan from a landscape architect and a source, or sources, to buy trees. Time was<br />

short. It was also dawning on me that I was 63 years old and I was starting an endeavor that by its<br />

nature is long range and slow to fruition. Putting that aside, I focused on the fact that this could be<br />

of benefit to others.<br />

While waiting for Tony’s visit, I got busy. Brad Harrison, a federal area representative for the Soil<br />

Conservation Service of the USDA Farm Service Agency in Adel, Iowa (now the Natural Resources Conservation<br />

Service), helped get my original 80 acres of land into the Conservation Reserve Program. Forty more acres would<br />

eventually be added but I would have to wait on that until I could purchase it from my nephew, Charlie Brandt. 8<br />

Getting into the CRP program insured our arboretum could receive some federal grant payments in<br />

exchange for keeping acres of farmland out of production and in natural habitat. As part of this<br />

effort, the Farm Service Agency also provided aerial photos of our land.<br />

Again, I resumed talking to people in and around Des Moines looking for just the right<br />

source for trees. Bob Rennebohm, owner of Heard Gardens, 9 said he could supply me with trees<br />

from known sources. Joe Oppe, formerly a manager of a small arboretum in Florida and now an<br />

employee at Des Moines Parks and Recreation, offered to help with initial planting and oversight in<br />

his spare time. He also advised me to stake, water, and mulch my plantings. He felt that with such a windy, exposed<br />

site a windbreak to the west might be needed to give the smallest trees three to five feet of protection or we should<br />

start some of the more tender species in a nursery.<br />

Scott Stouffer, a Des Moines architect with Charles Herbert and Associates who designed<br />

the Civic Center of Greater Des Moines, offered advice and later provided architectural work for<br />

the arboretum. Finally, Jeff Logsdon, director of the Dallas County Conservation Board, felt<br />

strongly that I needed to write down in some detail my thoughts about the land and why I wanted to<br />

do this project. He thought that such a treatise would give the project a philosophy to guide it as it<br />

evolved. He was a visionary. I took his advice. He also introduced me to satellite imaging of the<br />

land, which proved to be very useful as the master plan was developed.<br />

On November 22, 1996, Tony Tyznik arrived in Dallas Center to take a look at the<br />

arboretum site. This was an exciting development that occurred just a few days before<br />

Thanksgiving. We spent the day talking and walking the land. It was a very muddy day for<br />

walking; thankfully he bought rubber boots for the occasion. Tony is completely to my liking: a<br />

modest outdoorsmen, sure of himself, very careful, pensive, and extremely knowledgeable about<br />

tree characteristics, master planning, and proper siting. After all, landscape planning and design had<br />

Kentucky coffeetree (Gymnocladus dioicus) at dawn.<br />

25

Tony Tyznik’s original landscape design<br />

would be modified and updated<br />

continuously throughout his partnership<br />

with the <strong>Arboretum</strong>.<br />

26

een his world at the Morton <strong>Arboretum</strong> for years. Tony was in his early 70s and vigorous. I would<br />

come to learn he was also an artist. He paints master plans in his mind and then assigns them to<br />

paper. It is his art form. He later gave Sue and me six large, wonderful prints of his pen-and-ink<br />

line drawings of trees that we gave to the arboretum. Tony saw great potential in this land, its<br />

significant relief, its bowl effect, its water, and its openness.<br />

He concurred that I needed to acquire my nephew’s 40 acres. He also thought I should<br />

create a lake or pond in the center of the property. He wanted an aerial map with two-foot scale that<br />

would give him the detail he needed to paint his design for the master<br />

plan. His ideas, Tony knew from experience, would spring to<br />

life from studying this map.<br />

He also wanted soil samples with pH readings and a<br />

soil map with soil porosity characteristics. 10 Tony was ready to<br />

go, and I could have found no better person. He dined with our<br />

family, and then we made an agreement. He would charge a<br />

very reasonable fee and go to work<br />

immediately after receiving the aerial<br />

map with close contour lines. We<br />

were moving! This project was his<br />

from 1997 until 2011 when he<br />

retired. It was a near perfect match.<br />

We shared a deep reverence for the<br />

natural world, and Sue and I became<br />

his good friends.<br />

Tony Tyznik was a<br />

gifted landscape<br />

architect and artist.<br />

His series of Tree<br />

Portraits illustrates<br />

his profound talent.<br />

8. Charlie Brandt is the son of my deceased sister, Mary Elizabeth <strong>Brenton</strong> Brandt.<br />

9. Heard Gardens was a garden center and nursery established in 1928 in Johnston, Iowa, later acquired by Wright Tree<br />

Service.<br />

10. Soil porosity refers to the amount of pore or open space between soil particles. Pores are created by the contacts<br />

made between irregular shaped soil particles. Fine-textured soil has more pore space than coarse textured because<br />

you can pack more small particles into a unit volume than larger ones. Fine textured clay soils hold more water<br />

than coarse textured sandy soils.<br />

27

28

I had one piece of the puzzle in place. But I kept coming back to the same questions. What would<br />

I plant, and from whom would I buy? Developing a tree list was convoluted. I had my own<br />

simplistic ideas about what I wanted. This was shaped by my first-hand walking knowledge and by<br />

a number of books that proved to be valuable resources. <strong>The</strong> books included Michael Dirr’s<br />

Manual of Woody Landscape Plants; Preston’s North American Trees; Ellins’ Trees of North<br />

America; Grimm’s <strong>The</strong> Book of Trees, (the book from Jane Eddy that was my inspiration); and<br />

Native Trees of Iowa. Of these, Dirr’s book is and was the most useful to me, particularly for nonnative<br />

species. Its breadth and depth included extensive commentary on growth habits, disease,<br />

geographic range, and, very importantly, Dirr’s own comments as to his impression of appearances.<br />

I combined insights from all of these books with information I had received from experts and<br />

supporters already mentioned as well as from anyone else I could catch!<br />

<strong>The</strong> initial tree list featuring Peter van der Linden’s comments evolved and became the list<br />

you can find on pages 36 and 37.<br />

Tony now had his list, but where could I find the trees? In early 1997, (already pretty late to<br />

order trees for 1997 spring planting as I later found out) I decided to go with Heard Gardens. Bob<br />

Rennebohm quoted me a price based on his cost plus a reasonable markup. He seemed fully<br />

capable and able to acquire most of the trees I wanted for my first year’s planting.<br />

All of this was a relief, but what had started out as a “tree garden” was now developing into<br />

a full-fledged and extensive arboretum. I was still trying to get my arms around what that meant. I<br />

needed to put my thoughts in writing. This plan needed to be carefully communicated to Tony<br />

before he proceeded with the master plan.<br />

In January and February 1997, I summarized my thoughts, quoted here from my notes:<br />

<strong>The</strong> arboretum concept grew out of a love of trees. <strong>The</strong>refore, my thought is to have<br />

trees be the main event of the arboretum. If, over time, I have the planting space and<br />

knowledge or both, hired or acquired, for planting non-woodies, shrubs and an<br />

understanding of small trees, I will move in those directions also.<br />

<strong>The</strong> central idea is to create an arboretum using loose clusters, mainly in specimen<br />

array, for 24 to 36 species of larger canopy trees hardy in central Iowa. Each cluster<br />

would have its own design and be able to be viewed separately or independently. It is<br />

my thought that knowledge and awareness and love of trees may best come from the<br />

Alder Bridge crosses the stream in the alder (Alnus glutinosa) collection.<br />

29

impact of the viewing of one species all at once in a major grouping. <strong>The</strong>refore, I<br />

would propose to use 10 to 20 similar trees in each loose grouping.<br />

It may be that a closely related species or two within the same genus might be in<br />

close proximity to this main species cluster, but the integrity of the one species per<br />

cluster would be maintained as much as possible.<br />

In addition to providing much pleasure to me, the arboretum needs to be for public<br />

entry, study, learning, and enjoyment. Space then needs to be set aside for a building<br />

or two for class, lectures, convening of groups, as well administration, and a<br />

separate adjoining area for storage and machines.<br />

Although I plan to fund the arboretum, I think that it might be owned as an adjunct to<br />

our family <strong>Brenton</strong> Farm Company, or as a private operating foundation, or attached<br />

to a public institution or foundation.<br />

I project that the operating budget for the next 10 years or so, exclusive of the cost of<br />

materials and capital expenses, should be in the $25,000 per year area. But with the<br />

ability to use existing farm machinery and labor to some extent, this should be the<br />

equivalent of $40,000 or so per year of operating costs. (Note: This proved to be too<br />

low once we got going.)<br />

<strong>The</strong> arboretum should be laid out with numerous roads and walkways and parking<br />

areas. It would seem that its location in central Dallas County is ideal because of its<br />

proximity to the Des Moines area, more so all the time as Des Moines expands to the<br />

west.<br />

View to oak (Quercus) collection in summer; the difference and variety within the genus is apparent.<br />

30

<strong>The</strong> chief purpose of the arboretum is education and awareness. It is hoped that the<br />

public, as they visit the arboretum, will leave the experience with a clear idea of the<br />

differences and distinctions in shape, texture, feel, and use of different tree species. It<br />

will be our goal to help shape and implant in the visitor the clear and distinctive<br />

differences and individual identity of each species.<br />

To accomplish this, in addition to a brochure, the design of the arboretum will group<br />

trees of one species in sufficient quantity and individual display arrangements so that<br />

there is a visual impact brought about by the commonality of the entire similar<br />

group. Each group of single or closely related and appearing species should be in its<br />

own design and be able to be viewed in its entirety from one or several physical<br />

places so as to strengthen the impression of their identity and characteristics. Most of<br />

the trees, then, within the arranged design will need to be sufficiently set apart from<br />

one another to allow for full and uninhibited growth and development.<br />

This, then, is the hope: that like a fine arts retrospective by one artist, an<br />

understanding of each species will come about as the visitor experiences the feeling<br />

of seeing the multi-tree design of a distinctive species of a dozen or so trees in display<br />

form.<br />

By early February I was facing a number of situations that needed quick attention. Tony<br />

could not complete his work, and thus we could not plant trees, until he received firm boundary<br />

markers for the small-scale topographical arboretum map provided by Aerial Photographics of<br />

Cedar Falls. Unfortunately, we were going to have to wait until the snow cover was gone to make<br />

that happen. It was not until March 3 that Tony received this information. Now, he could work.<br />

Reality was setting in. We were actually doing this. And now I had to deal with a few<br />

practical matters, some of which I knew very little about. Deer are plentiful in Iowa and they enjoy<br />

grazing or browsing on young trees. Browsing and buck rubbing can severely injure, deform, or<br />

even kill young trees.<br />

We had to explore the best way to protect the trees, and we had to do it quickly because<br />

planting was just around the corner. We also needed to resolve the issues of how we were going to<br />

get water to the trees and where the large quantities of mulch would come from. And then there was<br />

the aforementioned grid system. We couldn’t plant the trees until we determined known locations,<br />

and without a grid we wouldn’t be able to find them on a map after we planted them!<br />

This was a busy time. I have always enjoyed keeping a log of my activities regarding the<br />

arboretum and I’ve done so from Day One to the present. Looking back, it’s interesting to see the<br />

many notes I logged in the early part of 1997 leading up to the first tree planting on May 11.<br />

Starting in January, I met with Vic Scott, an area nurseryman, about using his company for tree<br />

purchasing and planting. <strong>The</strong> next day, I received a master planning proposal from Tom Dunbar of<br />

31

Des Moines and shortly thereafter, I spoke with Arnold Webster in Cedar Falls about getting a<br />

valuation of our existing trees. <strong>The</strong>y turned out to have very little value, but it was a step.<br />

I also needed to know how much the land was worth. I spoke with Bob Davis of Hertz Farm<br />

Management who appraised it from $2,000 to $2,500 an acre. It was very helpful to have this<br />

informative estimate. A few months later, John Walkowiak of the Iowa Department of Natural<br />

Resources came out to inventory our existing native tree stock. <strong>The</strong> land had Siberian elm, box<br />

elder, willow, green ash, red cedar, and walnut trees, most of which are still there as of today.<br />

I spoke again with Pam Nagel, and she offered a helpful reminder that finding a source of<br />

water for the trees should be at the top of my to-do list. On January 18 I drilled a hole through the<br />

ice in what we now call Overlook Pond to determine its depth and resultant capacity to supply<br />

water. It was 10 feet at the deepest point. Just a few days later, I met with William Harold “Bill”<br />

<strong>Brenton</strong>, who manages <strong>Brenton</strong> Brothers and is my brother Bob’s son. Some of <strong>Brenton</strong> Brothers’<br />

land is adjacent to the arboretum. Bill’s office is in Dallas Center, making it convenient for me to<br />

stop over and talk to him as questions arose. This time, we discussed ways to get water to my site.<br />

He offered to help me find field help for planting, watering, etc. He also found a four-wheel drive<br />

used Ford pickup truck for me to purchase for the arboretum as well as a 475-gallon water tank and<br />

<strong>The</strong> original water wagon is still in use today.<br />

32

a small water pump. <strong>The</strong> tank and pump would fit on the water wagon <strong>Brenton</strong> Brothers was<br />

fashioning for me from a hayrack chassis. Early on, Bill also helped us pull the abandoned barbed<br />

wire and other debris out of my nephew Charlie’s ditch on the east side of the entry road.<br />

Throughout this process, it became clear that it didn’t hurt to have <strong>Brenton</strong> Brothers next door<br />

running a farm operation.<br />

In February, I met with Rae Boysen, manager of the Iowa <strong>Arboretum</strong>. She felt that we<br />

should start our plants in a nursery and encouraged me to create a windbreak for the property by<br />

planting trees on the north and northwest perimeter to reduce the impact of strong winds. She<br />

offered to help purchase trees for us at reduced cost and explained how to buy our trees at<br />

wholesale prices once the arboretum received not-for-profit status from the I.R.S. This was most<br />

helpful.<br />

My next meeting, which happened just<br />

a few days before Valentine’s Day, was course<br />

setting. I had the pleasure of speaking for the<br />

first time with Dr. George Ware of the Morton<br />

<strong>Arboretum</strong>. George, now deceased, was a<br />

world-renowned plantsman who specialized in<br />

the elm genus. He collected elm seeds from all<br />

over the world, particularly China, then grew,<br />

crossed, and bred them at Morton. He wanted<br />

to give me some of these little trees for our<br />

arboretum. He set aside 40 elm saplings and a<br />

few other small tree species in pots. I drove<br />

over and put all of these in my station wagon<br />

and headed home. <strong>The</strong> larger trees were planted<br />

at the arboretum that spring and the seedlings I<br />

over-wintered at my home in Des Moines. This<br />

started a new, cordial, and valuable<br />

relationship. Over the years, we have planted<br />

many of George’s elms, which helped us<br />

establish a substantial elm tree collection.<br />

Dr. George Ware discusses elms (Ulmus spp.) with<br />

visitors at <strong>The</strong> <strong>Brenton</strong> <strong>Arboretum</strong>.<br />

Later that month, much to my relief, I<br />

was able to order mostly from Heard Gardens all of the trees that would be planted that spring.<br />

Owner Bob Rennebohm then led me to Wright Tree Service of Des Moines for wood chip mulch.<br />

<strong>The</strong>y stocked their chips just west of Waukee, close to Highway 6, which meant I could borrow a<br />

truck from <strong>Brenton</strong> Brothers and pick them up free of charge. I also bought a number of field<br />

supplies, such as shovels, hoses, and wheelbarrows.<br />

I enjoyed getting my hands dirty, but soon I was back in the office. This time I was calling<br />

33

Jim Hocksteller, a local surveyor, to get the exact land boundaries Tony still needed. We finally got<br />

the aerial shots and land surveys Tony needed to do his work. This was very good news! Now I was<br />

ready to intensify talks with my nephew about his land. It was becoming clear I fervently needed to<br />

purchase Charlie’s 40 acres or trade some of my land for his in order to complete the arboretum. He<br />

was willing, but still needed time to consider it all. Despite not having reached an agreement, I told<br />

Tony to include those 40 acres in the master plan. I would try not to plant on them until a purchase<br />

took place.<br />

Highlighted in red on the county assessor’s map, it’s easy to see how crucial the purchase<br />

of land from Charlie Brandt was to the overall <strong>Arboretum</strong>.<br />

34

Spring was in bloom, but there was an issue with some of the trees we had ordered for our<br />

first planting. I was a bit discouraged. I met with Bob Rennebohm to try to determine which of the<br />

trees we had already ordered would actually be coming and which would not. Over the years, I’ve<br />

now learned that wholesale nurseries change their availability of stock depending on many factors,<br />

including winter weather conditions and the resultant condition of plant stock in the spring. In this<br />

case, we had to pare our spring planting list down to about 300 trees with the hope of planting more<br />

in the fall. Others had already spoken to me about the dangers of fall planting for certain species,<br />

which was another reason I was disappointed we couldn’t get all of the trees for spring. We did end<br />

up planting some trees in the fall of 1997, which set a future pattern of planting both in the spring<br />

and fall. And, in the years to come, we learned to get an earlier start on tree ordering, which helped<br />

us with the issue of availability.<br />

Looking ahead, I had another, quite daunting, issue to consider. Turning my attention from<br />

trees to bridges, I met with Charlie Rhinehart of Dallas Center. Charlie’s family had been life-long<br />

friends of my extended family going back three generations. His aunt, Helen Rhinehart, had worked<br />

with Dad as a senior <strong>Brenton</strong> Bank holding company officer for many years. Charlie and I<br />

discussed building a bridge over Hickory Creek, which at that time separated the east and west<br />

sections of the arboretum. It had become clear this was an absolute necessity because, as we started<br />

planting, the only vehicle access to the west side of the proposed arboretum was through <strong>Brenton</strong><br />

Brothers farm. That was a time-consuming and inefficient way to get work done at the arboretum.<br />

We had identified the problem, but it would take months to build the bridge.<br />

<strong>The</strong> North Bridge, near the willows, was built low to the ground ensure that it would<br />

blend into the landscape. In this picture the structure practically disappears.<br />

35

Buz’s original plant list with comments and additions from Peter van der Linden.<br />

36

37

38

Planting day was near. Now I needed to place the trees as detailed in the master plan at the correct<br />

locations in the ground. But our 200-foot x100-foot grid system would not be developed until next<br />

year. I was going to have to do this the old-fashioned way: I went into the field and measured with<br />

a long tape. Using a compass for direction from known locations on the master plan (i.e. bridge,<br />

road, tree, pond, stream), I found the approximate spot for each planting. This method worked<br />

pretty well, but I wouldn’t recommend it to others. Some errors inevitably occurred, and we found<br />

them later, but I needed to get going! And it did get us going.<br />

On May 11, we planted our first tree, a white spruce, labeled as number 97-001. That spring<br />

we also planted American beech; Chinese chestnut; burr, swamp, pin, shingle, and red oaks;<br />

tuliptree; sycamore; green and white ash (‘Patmore’ and ‘Autumn Purple’ cultivars); gingko;<br />

Colorado blue, white, Serbian, and Black Hills spruce; Canadian hemlock; white (concolor) fir;<br />

Kentucky coffeetree; and Ohio buckeye.<br />

We had a wonderful group of people who helped with our first plantings. Bob German, a<br />

former <strong>Brenton</strong> Bank president; Bill Scott; my son Ken <strong>Brenton</strong>; Emily Hicklin; John Mortimer of<br />

Dallas Center; Mike Thomas; and Pam Nagel all helped in this effort. 11 It was a very exciting day.<br />

Bob German used a small tractor-mounted tree spade to pre-dig all of the tree holes I had staked<br />

earlier. We also had our newly acquired water wagon on hand and plenty of wood chips for mulch.<br />

<strong>The</strong> procedure for planting the trees worked well: German dug the hole, and once the tree was<br />

planted (not too deep!), we refilled the hole with dirt, then watered, mulched, and staked.<br />

Two hundred trees were planted this way. By early June we had finished planting trees for<br />

the spring. Plantings included seven elms from the Morton <strong>Arboretum</strong>; 10 chinkapin oaks, six<br />

tuliptrees, six red maples, and 12 sugar maples. By fall, we added a total of about 50 trees,<br />

including white ash, hop hornbeam, silver maple, hackberry, lindens and white cedar. <strong>The</strong> rains<br />

came just right for us. Within the next year, we added honey locust, hackberry, ginkgo, hemlock,<br />

more Black Hills spruce, white pine, sugar maple, catalpa, and white oak.<br />

After our initial planting in June 1997, I left for the entire month of July on a sailing trip<br />

from Alaska to Seattle. Bill Scott agreed to look after the trees while I was away, watering and<br />

restaking as needed. Bill did it for his love of trees and respect for the project. I am so appreciative.<br />

He had much more productive things to do. I also hired Clem Evans, an area resident and jack-ofall-trades,<br />

to help, and both continued on after I returned. <strong>The</strong> rains did come during summer 1997,<br />

but Bill and Clem watered also and gave the trees very careful attention. <strong>The</strong> help was invaluable.<br />

Clem worked six years after that.<br />

Black walnut (Jugans nigra) near Walnut Bridge.<br />

39

<strong>The</strong> first day of planting, May 11, 1997, included Kenneth <strong>Brenton</strong>, John Mortimer, Bob German, and Pam Nagel.<br />

<strong>The</strong>re were many matters to work on upon my return. It soon became apparent that the deer<br />

had found our trees. A decision on fencing was immediately needed. I decided to place 5-foot-high<br />

9-gauge woven wire around each tree for deer protection. This method of tree protection was used<br />

for a number of years on many tiny trees, and in fact is still in limited use today. That summer and<br />

fall of 1997 we ringed all of 200 of our trees.<br />

At the same time, talks continued with Charlie Brandt. By 1998, he had fully agreed to sell<br />

his 40 acres for $2,000 per acre and some participation in development profits of adjoining <strong>Brenton</strong><br />

land should this occur. Looking back it’s clear nothing could have been more important than<br />

acquiring this land. Charlie’s willingness to sell was never questioned, but issues about the way to<br />

do it, the careful negotiations, and the thoroughness with which he approached the sale made for<br />

much communication over many months. It was so important for the arboretum to have this land.<br />

To finally have it behind me made a huge difference in my energy to move on with so much more.<br />

<strong>The</strong> sale took place in August 1998.<br />

A series of things happened at the end of 1997 and into 1998, all of which had a great<br />

impact on the arboretum’s future:<br />

<br />

Tony Tyznik designed and we built a cement bridge to connect the east and west arboretum<br />

land. It has worked well.<br />

40

We built a road through the arboretum. Per Tony’s direction, I staked it out in October of 1998.<br />

His plan also called for us to create a small lake by damming the stream from the north (the<br />

west branch of Hickory Creek). I started to talk to engineers about accomplishing this.<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

We established a small tree nursery along the protected east side of “Charlie’s Ditch.” <strong>The</strong><br />

nursery would temporarily hold small trees we would later plant and also hold excess trees we<br />

purchased. This was all completed in 1997.<br />

We started talking with professional turf people. I knew I wanted to get rid of quite a bit of the<br />

brome and alfalfa ground cover (most of the arboretum land had been a pasture) in order to<br />

plant native prairie grasses. <strong>The</strong>se ideas were just forming.<br />

<strong>The</strong> 200-foot x 100-foot grid system was completed in the fall and the red marker caps went on<br />

stakes soon thereafter. Next, a tree numbering system, much like the one used by the<br />

Bickelhaupts, was started. <strong>The</strong> first tree, 97-001, was a white spruce.<br />

Here Buz is planting a conifer on the western side of the property.<br />

In December of 1997, we got the wonderful news that <strong>The</strong> <strong>Brenton</strong> <strong>Arboretum</strong> was now a<br />

public arboretum. It was incorporated under I.R.S. rules as a private operating foundation. <strong>The</strong><br />

original board consisted of myself as chair, plus Sue <strong>Brenton</strong> and our three children, Kenneth,<br />

Lockie, and Julie Ann, as the first officers. Soon after, we received I.R.S. tax-exempt status so any<br />

donations would be deductible for tax purposes.<br />

41

Tony returned to the arboretum to discuss his master plan. He agreed to give me a grading<br />

plan for the proposed lake (first called Ziba’s Lake, named for my deceased sister, Mary “Ziba”<br />

Elizabeth, but later changed to Lake Homestead). He also provided designs for footbridges that<br />

would take visitors over streams and along walking paths, and he created tree-planting plans for<br />

1998. He also helped me think through issues of groundcover. Tony’s opinion was that he favored<br />

shorter prairie grasses over taller.<br />

Andy Schmitz and Jon Judson of Diversity Farms prepare to seed the tallgrass prairie.<br />

Within the year, we consulted with Dr. Dorothy Berringer, a noted Iowa grasses expert. We<br />

discussed planting short prairie grasses on the west side and taller prairie grasses on the east side.<br />

This discussion led to the planting of buffalo and blue grama grasses on the west side and little blue<br />

stem and sideoats grama on the east along with small numbers of prairie forbs. <strong>The</strong>se ground turf<br />

plantings were completed in 1998.<br />

While Tony was at the arboretum, we started a serious discussion about building a lake. <strong>The</strong><br />

two of us met with Tim Daugherty, a local earthmover and grader, but Tim felt the job was<br />

probably too big for him. Within the year, we set up another meeting with Rick Baumhover of the<br />

engineering firm Kirkham Michael. In looking at our land, he said it was apparent that the west<br />

branch of Hickory Creek, which flowed from the north through the arboretum, would at flood stage<br />

discharge too much water into Lake Homestead for it to contain. <strong>The</strong> water surge would not only<br />

inundate the small lake from time to time, it would also cause silt to build up over a few years. <strong>The</strong><br />

42

three of us decided to use the smaller flow of water from the east creek and divert the west branch<br />

of Hickory Creek around and to the west of our lake. This would create a better balance between<br />

the size of the lake and the water flowing into it. As it has turned out, we continue to have siltation<br />

problems emanating from the east creek.<br />

But in 1998, these water flow changes seemed the only way out of our dilemma. Diverting<br />

the west branch of Hickory Creek around the lake was a big and costly undertaking, calling for an<br />

additional $100,000. This was our plan, however, and we followed through in creating the lake<br />

using the smaller stream as a water source. <strong>The</strong> U.S. Corps of Engineers required the three large<br />

discharge culverts through the dam on the west side of the lake so that the dam could withstand the<br />

standard 100-year flood.<br />

As our first year came to a<br />

close, I met Jeff Iles, director of<br />

horticulture at Iowa State University,<br />

later head of the Department of<br />

Horticulture. This meeting would<br />

prove to be one of the most useful and<br />

satisfying relationships I have had at<br />

the arboretum. He encouraged me. He<br />

taught me. He gave me time and<br />

attention and later joined our board of<br />

directors. As of 2015, he is still a board<br />

member. His knowledge of trees is<br />

second to none. This was just one more<br />

reason why the first year of the<br />

arboretum’s existence would turn out<br />

to be as exciting a year and as<br />

important a year as any in my life.<br />

Dr. Jeff Iles discusses one of his favorite ornamental trees, the<br />

crabapple (Malus sp.). <strong>The</strong> <strong>Arboretum</strong> has an impressive collection of<br />

crabapples, each selected with his expert advice.<br />

43

44

<strong>The</strong> year began with a bang. We were close to opening <strong>The</strong> <strong>Brenton</strong> <strong>Arboretum</strong> to the public. We<br />

planted 350 more trees in the spring, mostly from Heard Gardens. Bob German dug the holes. Bill<br />

Scott and Clem Evans continued working part-time helping me get the arboretum ready. Bill and<br />

Clem relieved me of many daily chores. I continued to plant and water trees, but Clem and Bill<br />

made the difference.<br />

In April that year we turned our attention back to building a road through the arboretum.<br />

Charlie Rhinehart laid out woven, synthetic fabric for the base of the road along a path I had staked.<br />

He altered the position a bit from the master plan at several places, but essentially it was put in as<br />

designed by Tony. <strong>The</strong> bridge was by now usable so the full length of the road was operable.<br />

Crushed limestone rock was spread 12 feet wide over the cloth for the entire length of the road.<br />

This finished the job and very little grading was needed.<br />

It had become clear we also needed permanent tree tags. I used the Bickelhaupt tag as a<br />

model, and after some thinking and talking with others, I designed a heavy plastic 6-inch tag. <strong>The</strong><br />

tag incorporated the common and scientific tree name as well as the individual tree number.<br />

American Awards in Des Moines made the tags, which were quite similar to those at the<br />

Bickelhaupt <strong>Arboretum</strong>. Several hundred trees received tags that year. Those tags lasted ten years<br />

but now have been replaced with metal tags.<br />

Next, we had to figure out how to get rid of some of the existing grasses in the area. In early<br />

June, Charlie Rhinehart’s crew applied SELECT herbicide over a large area on the west side. This<br />

was done twice and, it turned out, did a pretty good job of killing the existing grasses, which we<br />

thought were primarily brome. We learned later that further treatments were needed. This herbicide<br />

allows the non-grass plants called forbs to live. <strong>The</strong>n, per instruction from Dorothy Berringer, we<br />

planted about 10 acres of buffalo and blue grama grasses on the west side.<br />

In developing a vision for the arboretum, I had all along wanted to avoid the park or golf<br />

course feel of bluegrass, which is mostly non-native yet widely planted. I wanted a more native and<br />

informal feel, and I wanted to escape a lot of mowing and fertilizing. Buffalo grass, although<br />

slightly out of native range in central Iowa, seemed to be the answer. Dorothy picked a mix for us<br />

she felt would work in our area. And so we planted. Looking back it probably was a mistake, for<br />

we have had to interseed with a fescue or entirely replace it because of weedy conditions. Although<br />

we escaped the bluegrass look, we did not escape fairly high maintenance costs, weedy conditions,<br />

and the need for replacing or augmenting.<br />

‘Sunburst’ honey locust (Gleditsia triacanthos) in spring.<br />

45

That wasn’t the only issue. Our recently completed bridge, although plenty sturdy, would<br />

not accept the heavy rush of water flowing under it during times of flooding. Water would flow<br />

over the bridge, and although it might only happen for short periods of time, would wash out gravel<br />

on top of the bridge and along the sides. We corrected this in 2011 by cementing the bridge’s<br />

approaches and surface. We were learning that the west branch of Hickory Creek, which comes<br />

from the north, bisects the arboretum from east to west, and drains about 1,400 acres, could be<br />

extremely powerful at flood stage.<br />

I was beginning to realize the scope (and cost) of what I had gotten myself into. I needed<br />

someone to help manage the arboretum. I hired Andy Schmitz, who had just graduated with a<br />

bachelor’s degree in horticulture from Iowa State University. He was from a large Waterloo family<br />

and wanted, if possible, to stay in Iowa. This association proved exceedingly beneficial and<br />

satisfying for Andy, the arboretum, and me. He continues to grow and prosper.<br />

Now I had the time, the energy, a plan for the funding, and Andy with whom to work. I was<br />

learning that Andy’s technical ability, work ethic, and commitment to the arboretum was a very<br />

significant factor in our early successful evolution. I was very fortunate to have him. Everything<br />

was now in place for the official grand opening of the arboretum.<br />

Andy Schmitz, Tony Tyznik, and Buz <strong>Brenton</strong> pose by the newly installed sign.<br />

46

On July 28, 1998, <strong>The</strong> <strong>Brenton</strong> <strong>Arboretum</strong> opened without fanfare. It was, however, a real<br />

milestone for us. Not long after we opened, we erected an entrance sign designed by Tony Tyznik<br />

that is still in use. By October, we hosted our first formal event. <strong>The</strong> Dallas Center High School<br />

cross-country team started to use the arboretum for training, which it—and others—still does.<br />

It was now apparent Andy needed an office, but there were no buildings on the grounds.<br />

Bob German gave us office and meeting space at no cost at the <strong>Brenton</strong> State Bank in Dallas<br />

Center. How nice!<br />

Andy and I met with several grade school teachers brought together by the superintendent<br />

of the Dallas Center-Grimes school district, Gary Sinclair. Our goal was to jointly devise a<br />

curriculum around the beginning study of trees, soil, and water. This would evolve into field study<br />

at the arboretum and be directed at children in grades one to three. We named it “Knee-High<br />

Naturalists.” This was our first effort in the educational area, now one of our cornerstones. I chose<br />

to concentrate on the younger children, thinking that their minds would be very open to new ideas,<br />

perhaps more so than older children. Some progress was made, but it would take a year or so to get<br />

our educational efforts off the ground.<br />

In 1999, for the first time, Andy and I were wondering about the need for tree pruning. Over<br />

the years, Andy has become very skilled at pruning the trees in our collection both for health and<br />

aesthetic appearance, but back then we were novices. Jerry Swim, a pruning consultant from<br />

Ankeny, toured the collection with us. His advice, which we have followed and built on ever since,<br />

was not to prune small trees for two or three years after planting, unless there were broken or<br />

seriously crossing branches. Later on we would learn how to prune a tree based on its desired<br />

scaffolding, starting with the lowest desired limbs and the separation of limbs as they grow up the<br />

trunk.<br />

That year we planted about 400 trees, including groups of pear trees, Osage orange,<br />

shellbark, Ohio buckeye, scotch pine, and swamp white oak. <strong>The</strong>se plantings were all done in<br />

accordance with the master plan. But now we had another small, nasty problem. Musk thistle was<br />

emerging all over the arboretum. This was a real problem for five years or more. We had to cut or<br />

pull it each year. Also, pocket gophers were burrowing around some of our oak trees and eating<br />

roots. Several trees died from this. <strong>The</strong> pocket gopher problem persisted for many years.<br />

Problems aside, we started to focus on our collection philosophy. Although we didn’t adopt<br />

it as a formal policy until later, our philosophy was emerging in terms of the type of woody plants<br />

we wanted to grow. Our goal was to plant all of the trees and shrubs outlined in the master plan.<br />

This immediately put us in the business of planting many non-native as well as native trees. We had<br />

become, by default, a place for a very diverse woody plant collection, well beyond a concentration<br />

of native species. Some of the non-native trees (such as American chestnut, dawn redwood,<br />

sweetgum) would have trouble thriving. After all, redwoods, sweetgums, and a number of others<br />

would be well out of their natural growing range. In the case of the redwood, we lost them all for<br />

four or five years before finally succeeding.<br />

47

Castanea dentata, American chestnut at <strong>The</strong> <strong>Brenton</strong> <strong>Arboretum</strong>.<br />

<strong>The</strong> American chestnut had been eliminated from the eastern hardwood forest in the early<br />

years of the twentieth century because of a lethal blight, but as of 2015 ours are still growing.<br />

We also wanted to have a physical concentration of Iowa native trees so we designated an<br />

area to the north as our Iowa Collection. Here we planned to plant all the Iowa trees and shrubs that<br />

would grow on the site. Forest and Shade Trees of Iowa by van der Linden and Farrar was most<br />

helpful in guiding our species selection in that area. <strong>The</strong> Iowa Collection still remains, and now a<br />

looped walking path meanders through it.<br />

I also was eager to try as many non-native trees as possible so we kept planting them. Most<br />

are making it and thriving. Some, as mentioned, just exist and are likely to be taken out. <strong>The</strong><br />

bottom line is that the collection grew from what we wanted and was later codified.<br />

By 2000, the board of directors, established three years earlier, had expanded and was fully<br />

engaged. We held two meetings that year, with special meetings interspersed. In the year 2000,<br />

board members included Buz <strong>Brenton</strong>, chairman; Sue <strong>Brenton</strong>, vice chair, Julie <strong>Brenton</strong> Galbraith<br />

and Ken <strong>Brenton</strong>, secretary and treasurer; Lockie <strong>Brenton</strong> Markusen; Bob German; Dr. Jeff Iles;<br />

Peter van der Linden; and Jim Van Werden. 12 This board was active. Copies of the minutes of the<br />

two board meetings in 2000 follow.<br />

48

49

50

51

52

In August, we printed our first<br />

general arboretum brochure. Ray Hansen of<br />

Hansen Printing printed these and many<br />

subsequent items for us. Between the<br />

brochure and a new front entrance sign, I<br />