Times of the Islands Summer 2019

Presents the "soul of the Turks & Caicos Islands" with in-depth features about local people, culture, history, environment, businesses, resorts, restaurants and activities.

Presents the "soul of the Turks & Caicos Islands" with in-depth features about local people, culture, history, environment, businesses, resorts, restaurants and activities.

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

That <strong>the</strong>se magnificent creatures, <strong>the</strong> largest our<br />

planet has ever seen, were hunted almost to extinction<br />

less than 60 years ago hardly seems possible. The consuming<br />

quest for quick riches from slaughtered whales<br />

to fuel <strong>the</strong> demand for lamp oil, buggy whips, and cheap<br />

meat for an industrializing world might well have denied<br />

us that shared moment <strong>of</strong> intense common humanity on<br />

<strong>the</strong> sea—as well as all future generations.<br />

And that should give us pause for what our progeny<br />

may say about us 60 years from now. For even today, notwithstanding<br />

protections, whales face a future as uncertain<br />

and perilous as <strong>the</strong>y did when whalers relentlessly pursued<br />

<strong>the</strong>m across every ocean. In a hopeful twist <strong>of</strong> fate, however,<br />

<strong>the</strong> pristine waters surrounding <strong>the</strong> Turks & Caicos<br />

<strong>Islands</strong>, that once saw its share <strong>of</strong> whale hunting, could be<br />

a respite from modern perils, a sanctuary where whales<br />

thrive and perhaps befriend us.<br />

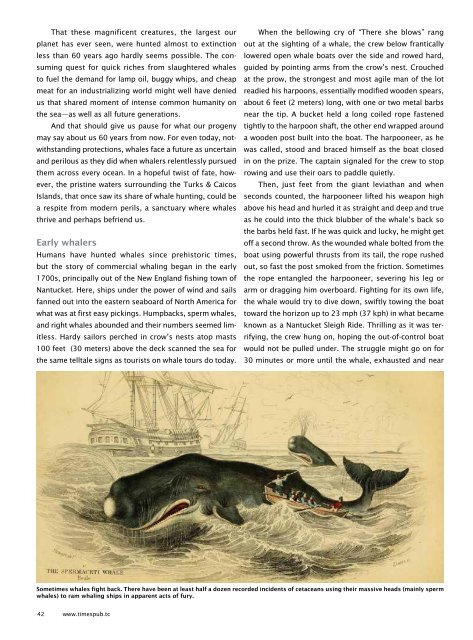

Early whalers<br />

Humans have hunted whales since prehistoric times,<br />

but <strong>the</strong> story <strong>of</strong> commercial whaling began in <strong>the</strong> early<br />

1700s, principally out <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> New England fishing town <strong>of</strong><br />

Nantucket. Here, ships under <strong>the</strong> power <strong>of</strong> wind and sails<br />

fanned out into <strong>the</strong> eastern seaboard <strong>of</strong> North America for<br />

what was at first easy pickings. Humpbacks, sperm whales,<br />

and right whales abounded and <strong>the</strong>ir numbers seemed limitless.<br />

Hardy sailors perched in crow’s nests atop masts<br />

100 feet (30 meters) above <strong>the</strong> deck scanned <strong>the</strong> sea for<br />

<strong>the</strong> same telltale signs as tourists on whale tours do today.<br />

When <strong>the</strong> bellowing cry <strong>of</strong> “There she blows” rang<br />

out at <strong>the</strong> sighting <strong>of</strong> a whale, <strong>the</strong> crew below frantically<br />

lowered open whale boats over <strong>the</strong> side and rowed hard,<br />

guided by pointing arms from <strong>the</strong> crow’s nest. Crouched<br />

at <strong>the</strong> prow, <strong>the</strong> strongest and most agile man <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> lot<br />

readied his harpoons, essentially modified wooden spears,<br />

about 6 feet (2 meters) long, with one or two metal barbs<br />

near <strong>the</strong> tip. A bucket held a long coiled rope fastened<br />

tightly to <strong>the</strong> harpoon shaft, <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r end wrapped around<br />

a wooden post built into <strong>the</strong> boat. The harpooneer, as he<br />

was called, stood and braced himself as <strong>the</strong> boat closed<br />

in on <strong>the</strong> prize. The captain signaled for <strong>the</strong> crew to stop<br />

rowing and use <strong>the</strong>ir oars to paddle quietly.<br />

Then, just feet from <strong>the</strong> giant leviathan and when<br />

seconds counted, <strong>the</strong> harpooneer lifted his weapon high<br />

above his head and hurled it as straight and deep and true<br />

as he could into <strong>the</strong> thick blubber <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> whale’s back so<br />

<strong>the</strong> barbs held fast. If he was quick and lucky, he might get<br />

<strong>of</strong>f a second throw. As <strong>the</strong> wounded whale bolted from <strong>the</strong><br />

boat using powerful thrusts from its tail, <strong>the</strong> rope rushed<br />

out, so fast <strong>the</strong> post smoked from <strong>the</strong> friction. Sometimes<br />

<strong>the</strong> rope entangled <strong>the</strong> harpooneer, severing his leg or<br />

arm or dragging him overboard. Fighting for its own life,<br />

<strong>the</strong> whale would try to dive down, swiftly towing <strong>the</strong> boat<br />

toward <strong>the</strong> horizon up to 23 mph (37 kph) in what became<br />

known as a Nantucket Sleigh Ride. Thrilling as it was terrifying,<br />

<strong>the</strong> crew hung on, hoping <strong>the</strong> out-<strong>of</strong>-control boat<br />

would not be pulled under. The struggle might go on for<br />

30 minutes or more until <strong>the</strong> whale, exhausted and near<br />

Sometimes whales fight back. There have been at least half a dozen recorded incidents <strong>of</strong> cetaceans using <strong>the</strong>ir massive heads (mainly sperm<br />

whales) to ram whaling ships in apparent acts <strong>of</strong> fury.<br />

42 www.timespub.tc