YSM Issue 91.1

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Science in the Spotlight<br />

The Great Quake<br />

By Vikram Shaw<br />

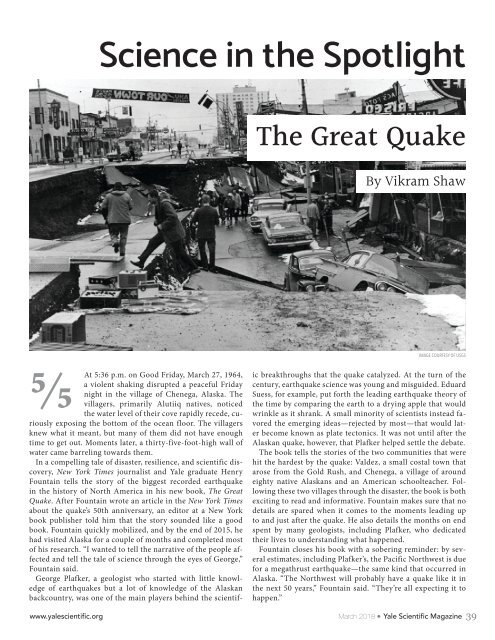

IMAGE COURTESY OF USGS<br />

5/5<br />

At 5:36 p.m. on Good Friday, March 27, 1964,<br />

a violent shaking disrupted a peaceful Friday<br />

night in the village of Chenega, Alaska. The<br />

villagers, primarily Alutiiq natives, noticed<br />

the water level of their cove rapidly recede, curiously<br />

exposing the bottom of the ocean floor. The villagers<br />

knew what it meant, but many of them did not have enough<br />

time to get out. Moments later, a thirty-five-foot-high wall of<br />

water came barreling towards them.<br />

In a compelling tale of disaster, resilience, and scientific discovery,<br />

New York Times journalist and Yale graduate Henry<br />

Fountain tells the story of the biggest recorded earthquake<br />

in the history of North America in his new book, The Great<br />

Quake. After Fountain wrote an article in the New York Times<br />

about the quake’s 50th anniversary, an editor at a New York<br />

book publisher told him that the story sounded like a good<br />

book. Fountain quickly mobilized, and by the end of 2015, he<br />

had visited Alaska for a couple of months and completed most<br />

of his research. “I wanted to tell the narrative of the people affected<br />

and tell the tale of science through the eyes of George,”<br />

Fountain said.<br />

George Plafker, a geologist who started with little knowledge<br />

of earthquakes but a lot of knowledge of the Alaskan<br />

backcountry, was one of the main players behind the scientific<br />

breakthroughs that the quake catalyzed. At the turn of the<br />

century, earthquake science was young and misguided. Eduard<br />

Suess, for example, put forth the leading earthquake theory of<br />

the time by comparing the earth to a drying apple that would<br />

wrinkle as it shrank. A small minority of scientists instead favored<br />

the emerging ideas—rejected by most—that would later<br />

become known as plate tectonics. It was not until after the<br />

Alaskan quake, however, that Plafker helped settle the debate.<br />

The book tells the stories of the two communities that were<br />

hit the hardest by the quake: Valdez, a small costal town that<br />

arose from the Gold Rush, and Chenega, a village of around<br />

eighty native Alaskans and an American schoolteacher. Following<br />

these two villages through the disaster, the book is both<br />

exciting to read and informative. Fountain makes sure that no<br />

details are spared when it comes to the moments leading up<br />

to and just after the quake. He also details the months on end<br />

spent by many geologists, including Plafker, who dedicated<br />

their lives to understanding what happened.<br />

Fountain closes his book with a sobering reminder: by several<br />

estimates, including Plafker’s, the Pacific Northwest is due<br />

for a megathrust earthquake—the same kind that occurred in<br />

Alaska. “The Northwest will probably have a quake like it in<br />

the next 50 years,” Fountain said. “They’re all expecting it to<br />

happen.”<br />

www.yalescientific.org<br />

March 2018<br />

Yale Scientific Magazine<br />

39