Aziz Art Sep 2019

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

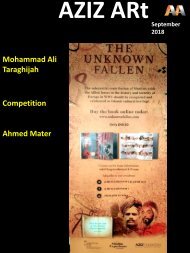

<strong>Aziz</strong> <strong>Art</strong><br />

<strong>Sep</strong> <strong>2019</strong><br />

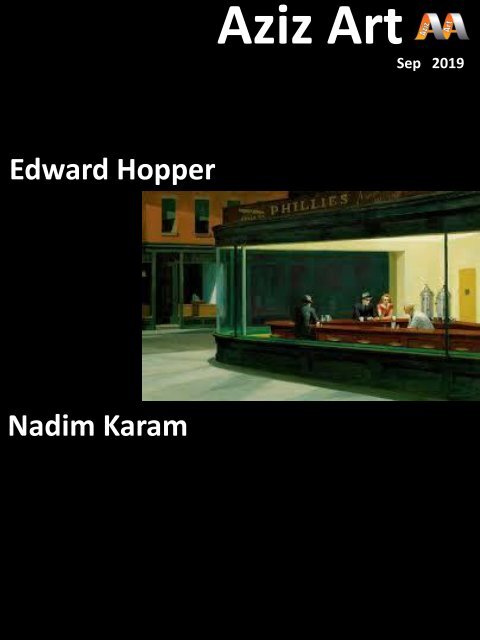

Edward Hopper<br />

Nadim Karam

1-Edward Hopper<br />

20-Nadim Karam<br />

Director: <strong>Aziz</strong> Anzabi<br />

Editor : Nafiseh Yaghoubi<br />

Translator : Asra Yaghoubi<br />

Research: Zohreh Nazari<br />

Iranian art department:<br />

Mohadese Yaghoubi<br />

http://www.aziz-anzabi.com

Edward Hopper<br />

July 22, 1882 – May 15, 1967<br />

was an American realist painter<br />

and printmaker. While he is best<br />

known for his oil paintings, he was<br />

equally proficient as a<br />

watercolorist and printmaker in<br />

etching. Both in his urban and<br />

rural scenes, his spare and finely<br />

calculated renderings reflected his<br />

personal vision of modern<br />

American life.<br />

Early life<br />

Hopper was born in 1882 in<br />

Upper Nyack, New York, a yachtbuilding<br />

center on the Hudson<br />

River north of New York City.He<br />

was one of two children of a<br />

comfortably well-to-do family. His<br />

parents, of mostly Dutch ancestry,<br />

were Elizabeth Griffiths Smith and<br />

Garret Henry Hopper, a dry-goods<br />

merchant.Although not so<br />

successful as his forebears, Garrett<br />

provided well for his two children<br />

with considerable help from his<br />

wife's inheritance. He retired at<br />

age forty-nine.Edward and his<br />

only sister Marion attended both<br />

private and public schools. They<br />

were raised in a strict Baptist<br />

home.His father had a mild nature,<br />

and the household was dominated<br />

by women: Hopper's mother,<br />

grandmother, sister, and maid.<br />

His birthplace and boyhood home<br />

was listed on the National Register<br />

of Historic Places in 2000. It is now<br />

operated as the Edward Hopper<br />

House <strong>Art</strong> Center.It serves as a<br />

nonprofit community cultural<br />

center featuring exhibitions,<br />

workshops, lectures, performances,<br />

and special events.<br />

Hopper was a good student in<br />

grade school and showed talent in<br />

drawing at age five. He readily<br />

absorbed his father's intellectual<br />

tendencies and love of French and<br />

Russian cultures. He also<br />

demonstrated his mother's artistic<br />

heritage. Hopper's parents<br />

encouraged his art and kept him<br />

amply supplied with materials,<br />

instructional magazines, and<br />

illustrated books. By his teens, he<br />

was working in pen-and-ink,<br />

charcoal, watercolor, and oil—<br />

drawing from nature as well as<br />

making political cartoons. In 1895,<br />

he created his first signed oil<br />

painting, Rowboat in Rocky Cove. It<br />

shows his early interest in nautical<br />

subjects<br />

1

In his early self-portraits, Hopper<br />

tended to represent himself as<br />

skinny, ungraceful, and homely.<br />

Though a tall and quiet teenager,<br />

his prankish sense of humor found<br />

outlet in his art, sometimes in<br />

depictions of immigrants or of<br />

women dominating men in comic<br />

situations. Later in life, he mostly<br />

depicted women as the figures in<br />

his paintings.In high school, he<br />

dreamed of being a naval architect,<br />

but after graduation he declared<br />

his intention to follow an art<br />

career. Hopper's parents insisted<br />

that he study commercial art to<br />

have a reliable means of income.<br />

In developing his self-image and<br />

individualistic philosophy of life,<br />

Hopper was influenced by the<br />

writings of Ralph Waldo Emerson.<br />

He later said, "I admire him<br />

greatly...I read him over and over<br />

again."<br />

Hopper began art studies with a<br />

correspondence course in 1899.<br />

Soon he transferred to the New<br />

York School of <strong>Art</strong> and Design, the<br />

forerunner of Parsons The New<br />

School for Design. There he studied<br />

for six years, with teachers<br />

including William Merritt Chase,<br />

who instructed him in oil<br />

painting.Early on, Hopper modeled<br />

his style after Chase and French<br />

Impressionist masters Édouard<br />

Manet and Edgar Degas.Sketching<br />

from live models proved a<br />

challenge and a shock for the<br />

conservatively raised Hopper.<br />

Another of his teachers, artist<br />

Robert Henri, taught life class.<br />

Henri encouraged his students to<br />

use their art to "make a stir in the<br />

world". He also advised his<br />

students, "It isn't the subject that<br />

counts but what you feel about it"<br />

and "Forget about art and paint<br />

pictures of what interests you in<br />

life."In this manner, Henri<br />

influenced Hopper, as well as future<br />

artists George Bellows and<br />

Rockwell Kent. He encouraged<br />

them to imbue a modern spirit in<br />

their work. Some artists in Henri's<br />

circle, including John Sloan, became<br />

members of "The Eight", also<br />

known as the Ashcan School of<br />

American <strong>Art</strong>.Hopper's first existing<br />

oil painting to hint at his use of<br />

interiors as a theme was Solitary<br />

Figure in a Theater (c.1904).During<br />

his student years, he also painted<br />

dozens of nudes, still life studies,<br />

landscapes, and portraits, including<br />

his self-portraits.

In 1905, Hopper landed a parttime<br />

job with an advertising<br />

agency, where he created cover<br />

designs for trademagazines.<br />

Hopper came to detest illustration.<br />

He was bound to it by economic<br />

necessity until the mid-1920s.<br />

He temporarily escaped by making<br />

three trips to Europe, each<br />

centered in Paris, ostensibly to<br />

study the art scene there. In fact,<br />

however, he studied alone and<br />

seemed mostly unaffected by the<br />

new currents in art. Later he said<br />

that he "didn't remember having<br />

heard of Picasso at all."He was<br />

highly impressed by Rembrandt,<br />

particularly his Night Watch, which<br />

he said was "the most wonderful<br />

thing of his I have seen; it's past<br />

belief in its reality."<br />

Hopper began painting urban and<br />

architectural scenes in a dark<br />

palette. Then he shifted to the<br />

lighter palette of the<br />

Impressionists before returning to<br />

the darker palette with which he<br />

was comfortable. Hopper later<br />

said, "I got over that and later<br />

things done in Paris were more the<br />

kind of things I do now."Hopper<br />

spent much of his time drawing<br />

street and café scenes, and going<br />

to the theater and opera. Unlike<br />

many of his contemporaries who<br />

imitated the abstract cubist<br />

experiments, Hopper was attracted<br />

to realist art. Later, he admitted to<br />

no European influences other than<br />

French engraver Charles Méryon,<br />

whose moody Paris scenes Hopper<br />

imitated.<br />

Years of struggle<br />

After returning from his last<br />

European trip, Hopper rented a<br />

studio in New York City, where he<br />

struggled to define his own style.<br />

Reluctantly, he returned to<br />

illustration to support himself.<br />

Being a freelancer, Hopper was<br />

forced to solicit for projects, and<br />

had to knock on the doors of<br />

magazine and agency offices to find<br />

business.His painting languished:<br />

"it's hard for me to decide what I<br />

want to paint. I go for months<br />

without finding it sometimes. It<br />

comes slowly."His fellow illustrator<br />

Walter Tittle described Hopper's<br />

depressed emotional state in<br />

sharper terms, seeing his friend<br />

"suffering...from long periods of<br />

unconquerable inertia, sitting for<br />

days at a time before his easel in<br />

helpless unhappiness, unable to<br />

raise a hand to break the spell."

In 1912, Hopper traveled to<br />

Gloucester, Massachusetts, to<br />

seek some inspiration and made<br />

his first outdoor paintings in<br />

America.He painted Squam Light,<br />

the first of many lighthouse<br />

paintings to come.<br />

In 1913, at the Armory Show,<br />

Hopper earned $250 when he<br />

sold his first painting, Sailing<br />

(1911), which he had painted<br />

over an earlier self-portrait.<br />

Hopper was thirty-one, and<br />

although he hoped his first sale<br />

would lead to others in short<br />

order, his career would not catch<br />

on for many more years.He<br />

continued to participate in group<br />

exhibitions at smaller venues,<br />

such as the MacDowell Club of<br />

New York.Shortly after his father's<br />

death that same year, Hopper<br />

moved to the 3 Washington<br />

Square North apartment in the<br />

Greenwich Village section of<br />

Manhattan, where he would live<br />

for the rest of his life.<br />

The following year he received a<br />

commission to create some movie<br />

posters and handle publicity for a<br />

movie company.Although he did<br />

not like the illustration work,<br />

Hopper was a lifelong devotee of<br />

the cinema and the theatre, both of<br />

which he treated as subjects for his<br />

paintings. Each form influenced his<br />

compositional methods.<br />

At an impasse over his oil paintings,<br />

in 1915 Hopper turned to etching.<br />

By 1923 he had produced most of<br />

his approximately 70 works in this<br />

medium, many of urban scenes of<br />

both Paris and New York.He also<br />

produced some posters for the war<br />

effort, as well as continuing with<br />

occasional commercial<br />

projects.When he could, Hopper<br />

did some outdoor watercolors on<br />

visits to New England, especially at<br />

the art colonies at Ogunquit, and<br />

Monhegan Island.<br />

During the early 1920s his etchings<br />

began to receive public recognition.<br />

They expressed some of his later<br />

themes, as in Night on the El Train<br />

(couples in silence), Evening Wind<br />

(solitary female), and The Catboat<br />

(simple nautical scene).<br />

Two notable oil paintings of this<br />

time were New York Interior (1921)<br />

and New York Restaurant (1922).He<br />

also painted two of his many<br />

"window" paintings to come: Girl at<br />

Sewing Machine and Moonlight<br />

Interior

oth of which show a figure<br />

(clothed or nude) near a window<br />

of an apartment viewed as gazing<br />

out or from the point of view from<br />

the outside looking in.<br />

Although these were frustrating<br />

years, Hopper gained some<br />

recognition. In 1918, Hopper was<br />

awarded the U.S. Shipping Board<br />

Prize for his war poster, "Smash the<br />

Hun." He participated in three<br />

exhibitions: in 1917 with the<br />

Society of Independent <strong>Art</strong>ists, in<br />

January 1920 (a one-man<br />

exhibition at the Whitney Studio<br />

Club, which was the precursor to<br />

the Whitney Museum), and in<br />

1922 (again with the Whitney<br />

Studio Club). In 1923, Hopper<br />

received two awards for his<br />

etchings: the Logan Prize from the<br />

Chicago Society of Etchers, and the<br />

W. A. Bryan Prize.<br />

Marriage and breakthrough<br />

By 1923, Hopper's slow climb<br />

finally produced a breakthrough.<br />

He re-encountered Josephine<br />

Nivison, an artist and former<br />

student of Robert Henri, during a<br />

summer painting trip in<br />

Gloucester, Massachusetts. They<br />

were opposites: she was short,<br />

open, gregarious, sociable, and<br />

liberal, while he was tall, secretive,<br />

shy, quiet, introspective, and<br />

conservative.They married a year<br />

later. She remarked: "Sometimes<br />

talking to Eddie is just like dropping<br />

a stone in a well, except that it<br />

doesn't thump when it hits<br />

bottom."She subordinated her<br />

career to his and shared his<br />

reclusive life style. The rest of their<br />

lives revolved around their spare<br />

walk-up apartment in the city and<br />

their summers in South Truro on<br />

Cape Cod. She managed his career<br />

and his interviews, was his primary<br />

model, and was his life companion.<br />

With Nivison's help, six of Hopper's<br />

Gloucester watercolors were<br />

admitted to an exhibit at the<br />

Brooklyn Museum in 1923. One of<br />

them, The Mansard Roof, was<br />

purchased by the museum for its<br />

permanent collection for the sum<br />

of $100. The critics generally raved<br />

about his work; one stated, "What<br />

vitality, force and directness!<br />

Observe what can be done with the<br />

homeliest subject."Hopper sold all<br />

his watercolors at a one-man show<br />

the following year and finally<br />

decided to put illustration behind<br />

him.

The artist had demonstrated his<br />

ability to transfer his attraction to<br />

Parisian architecture to American<br />

urban and rural architecture.<br />

According to Boston Museum of<br />

Fine <strong>Art</strong>s curator Carol Troyen,<br />

"Hopper really liked the way these<br />

houses, with their turrets and<br />

towers and porches and mansard<br />

roofs and ornament cast<br />

wonderful shadows. He always<br />

said that his favorite thing was<br />

painting sunlight on the side of a<br />

house."<br />

At forty-one, Hopper received<br />

further recognition for his work.<br />

He continued to harbor bitterness<br />

about his career, later turning<br />

down appearances and<br />

awards.With his financial stability<br />

secured by steady sales, Hopper<br />

would live a simple, stable life and<br />

continue creating art in his<br />

personal style for four more<br />

decades.<br />

His Two on the Aisle (1927) sold<br />

for a personal record $1,500,<br />

enabling Hopper to purchase an<br />

automobile, which he used to<br />

make field trips to remote areas of<br />

New England. In 1929, he produced<br />

Chop Suey and Railroad Sunset. The<br />

following year, art patron Stephen<br />

Clark donated House by the<br />

Railroad (1925) to the Museum of<br />

Modern <strong>Art</strong>, the first oil painting<br />

that it acquired for its<br />

collection.Hopper painted his last<br />

self-portrait in oil around 1930.<br />

Although Josephine posed for many<br />

of his paintings, she sat for only one<br />

formal oil portrait by her husband,<br />

Jo Painting (1936).<br />

Hopper fared better than many<br />

other artists during the Great<br />

Depression. His stature took a<br />

sharp rise in 1931 when major<br />

museums, including the Whitney<br />

Museum of American <strong>Art</strong> and the<br />

Metropolitan Museum of <strong>Art</strong>, paid<br />

thousands of dollars for his works.<br />

He sold 30 paintings that year,<br />

including 13 watercolors.The<br />

following year he participated in<br />

the first Whitney Annual, and he<br />

continued to exhibit in every<br />

annual at the museum for the rest<br />

of his life.In 1933, the Museum of<br />

Modern <strong>Art</strong> gave Hopper his first<br />

large-scale retrospective.<br />

In 1930, the Hoppers rented a<br />

cottage in South Truro, on Cape<br />

Cod.

They returned every summer for<br />

the rest of their lives, building a<br />

summer house there in 1934.<br />

From there, they would take<br />

driving<br />

trips into other areas when<br />

Hopper needed to search for<br />

fresh material to paint. In the<br />

summers of 1937 and 1938, the<br />

couple spent extended sojourns<br />

on Wagon Wheels Farm in South<br />

Royalton, Vermont, where Hopper<br />

painted a series of watercolors<br />

along the White River.<br />

however, he suffered a period of<br />

relative inactivity. He admitted: "I<br />

wish I could paint more. I get sick of<br />

reading and going to the<br />

movies."During the next two<br />

decades, his health faltered, and he<br />

had several prostate surgeries and<br />

other medical problems.But, in the<br />

1950s and early 1960s, he created<br />

several more major works,<br />

including First Row Orchestra<br />

(1951); as well as Morning Sun and<br />

Hotel by a Railroad, both in 1952;<br />

and Intermission in 1963.<br />

These scenes are atypical among<br />

Hopper's mature works, as most<br />

are "pure" landscapes, devoid of<br />

architecture or human figures.<br />

First Branch of the White River<br />

(1938), now in the Museum of<br />

Fine <strong>Art</strong>s, Boston, is the most<br />

well-known of Hopper's Vermont<br />

landscapes.<br />

Hopper was very productive<br />

through the 1930s and early<br />

1940s, producing among many<br />

important works New York Movie<br />

(1939), Girlie Show (1941),<br />

Nighthawks (1942), Hotel Lobby<br />

(1943), and Morning in a City<br />

(1944). During the late 1940s,<br />

Death<br />

Hopper died in his studio near<br />

Washington Square in New York<br />

City on May 15, 1967. He was<br />

buried two days later in the family's<br />

grave at Oak Hill Cemetery in<br />

Nyack, New York, his place of birth.<br />

His wife died ten months later.<br />

His wife bequeathed their joint<br />

collection of more than three<br />

thousand works to the Whitney<br />

Museum of American <strong>Art</strong>.Other<br />

significant paintings by Hopper are<br />

held by the Museum of Modern <strong>Art</strong><br />

in New York, The Des Moines <strong>Art</strong><br />

Center, and the <strong>Art</strong> Institute of<br />

Chicago.

Personality and vision<br />

Always reluctant to discuss<br />

himself and his art, Hopper<br />

simply said, "The whole answer is<br />

there<br />

on the canvas."Hopper was stoic<br />

and fatalistic—a quiet introverted<br />

man with a gentle sense of humor<br />

and a frank manner. Hopper was<br />

someone drawn to an emblematic,<br />

anti-narrative symbolism, who<br />

"painted short isolated moments<br />

of configuration, saturated with<br />

suggestion".His silent spaces and<br />

uneasy encounters "touch us<br />

where we are most vulnerable<br />

",and have "a suggestion of<br />

melancholy, that melancholy<br />

being enacted".His sense of color<br />

revealed him as a pure painter as<br />

he "turned the Puritan into the<br />

purist, in his quiet canvasses<br />

where blemishes and blessings<br />

balance".According to critic Lloyd<br />

Goodrich, he was "an eminently<br />

native painter, who more than any<br />

other was getting more of the<br />

quality of America into his<br />

canvases".<br />

Conservative in politics and<br />

social matters (Hopper asserted<br />

for example that "artists' lives<br />

close to them"),he accepted things<br />

as they were and displayed a lack of<br />

idealism. Cultured and<br />

sophisticated, he was well-read,<br />

and many of his paintings show<br />

figures reading.He was generally<br />

good company and unperturbed by<br />

silences, though sometimes<br />

taciturn, grumpy, or detached. He<br />

was always serious about his art<br />

and the art of others, and when<br />

asked would return frank opinions.<br />

Hopper's most systematic<br />

declaration of his philosophy as an<br />

artist was given in a handwritten<br />

note, entitled "Statement",<br />

submitted in 1953 to the journal,<br />

Reality.<br />

Great art is the outward expression<br />

of an inner life in the artist, and this<br />

inner life will result in his personal<br />

vision of the world. No amount of<br />

skillful invention can replace the<br />

essential element of imagination.<br />

One of the weaknesses of much<br />

abstract painting is the attempt to<br />

substitute the inventions of the<br />

human intellect for a private<br />

imaginative conception.

The inner life of a human being is<br />

a vast and varied realm and does<br />

not concern itself alone with<br />

stimulating arrangements of color,<br />

form and design.<br />

The term life used in art is<br />

something not to be held in<br />

contempt, for it implies all of<br />

existence and the province of art<br />

is to react to it and not to shun it.<br />

Painting will have to deal more<br />

fully and less obliquely with life<br />

and nature's phenomena before it<br />

can again become great.<br />

Though Hopper claimed that he<br />

didn't consciously embed<br />

psychological meaning in his<br />

paintings, he was deeply<br />

interested in Freud and the<br />

power of the subconscious mind.<br />

He wrote in 1939, "So much of<br />

every art is an expression of the<br />

subconscious that it seems to me<br />

most of all the important qualities<br />

are put there unconsciously, and<br />

little of importance by the<br />

conscious intellec.<br />

Methods<br />

Although he is best known for his<br />

oil paintings, Hopper initially<br />

achieved recognition for his<br />

watercolors and he also produced<br />

some commercially successful<br />

etchings. Additionally, his<br />

notebooks contain high-quality pen<br />

and pencil sketches, which were<br />

never meant for public viewing.<br />

Hopper paid particular attention to<br />

geometrical design and the careful<br />

placement of human figures in<br />

proper balance with their<br />

environment. He was a slow and<br />

methodical artist; as he wrote, "It<br />

takes a long time for an idea to<br />

strike. Then I have to think about it<br />

for a long time. I don't start<br />

painting until I have it all worked<br />

out in my mind. I'm all right when I<br />

get to the easel".He often made<br />

preparatory sketches to work out<br />

his carefully calculated<br />

compositions. He and his wife kept<br />

a detailed ledger of their works<br />

noting such items as "sad face of<br />

woman unlit", "electric light from<br />

ceiling", and "thighs cooler".<br />

For New York Movie (1939), Hopper<br />

demonstrates his thorough<br />

preparation with more than 53<br />

sketches of the theater interior and<br />

the figure of the pensive usherette.

The effective use of light and<br />

shadow to create mood also is<br />

central to Hopper's methods.<br />

Bright sunlight (as an emblem of<br />

insight or revelation), and the<br />

shadows it casts, also play<br />

symbolically powerful roles in<br />

Hopper paintings such as Early<br />

Sunday Morning (1930),<br />

Summertime (1943), Seven A.M.<br />

(1948), and Sun in an Empty Room<br />

(1963). His use of light and shadow<br />

effects have been compared to the<br />

cinematography of film noir.<br />

Although a realist painter,<br />

Hopper's "soft" realism simplified<br />

shapes and details. He used<br />

saturated color to heighten<br />

contrast and create mood.<br />

Subjects and themes<br />

Hopper derived his subject matter<br />

from two primary sources: one, the<br />

common features of American life<br />

(gas stations, motels, restaurants,<br />

theaters, railroads, and street<br />

scenes) and its inhabitants; and<br />

two, seascapes and rural<br />

landscapes. Regarding his style,<br />

Hopper defined himself as "an<br />

amalgam of many races" and not a<br />

member of any school, particularly<br />

the "Ashcan School".Once Hopper<br />

achieved his mature style, his art<br />

remained consistent and selfcontained,<br />

in spite of the numerous<br />

art trends that came and went<br />

during his long career.<br />

Hopper's seascapes fall into three<br />

main groups: pure landscapes of<br />

rocks, sea, and beach grass;<br />

lighthouses and farmhouses; and<br />

sailboats. Sometimes he combined<br />

these elements. Most of these<br />

paintings depict strong light and<br />

fair weather; he showed little<br />

interest in snow or rain scenes, or<br />

in seasonal color changes. He<br />

painted the majority of the pure<br />

seascapes in the period between<br />

1916 and 1919 on Monhegan<br />

Island.Hopper's The Long Leg<br />

(1935) is a nearly all-blue sailing<br />

picture with the simplest of<br />

elements, while his Ground Swell<br />

(1939) is more complex and depicts<br />

a group of youngsters out for a sail,<br />

a theme reminiscent of Winslow<br />

Homer's iconic Breezing Up (1876).<br />

Urban architecture and cityscapes<br />

also were major subjects for<br />

Hopper. He was fascinated with the<br />

American urban scene,

"our native architecture with its<br />

hideous beauty, its fantastic roofs,<br />

pseudo-gothic, French Mansard,<br />

Colonial, mongrel or what not,<br />

with eye-searing color or delicate<br />

harmonies of faded paint,<br />

shouldering one another along<br />

interminable streets that taper off<br />

into swamps or dump heaps."<br />

In 1925, he produced House by<br />

the Railroad. This classic work<br />

depicts an isolated Victorian wood<br />

mansion, partly obscured by the<br />

raised embankment of a railroad.<br />

It marked Hopper's artistic<br />

maturity. Lloyd Goodrich praised<br />

the work as "one of the most<br />

poignant and desolating pieces of<br />

realism."The work is the first of a<br />

series of stark rural and urban<br />

scenes that uses sharp lines and<br />

large shapes, played upon by<br />

unusual lighting to capture the<br />

lonely mood of his subjects.<br />

Although critics and viewers<br />

interpret meaning and mood in<br />

these cityscapes, Hopper insisted<br />

"I was more interested in the<br />

sunlight on the buildings and on<br />

the figures than any symbolism.<br />

" As if to prove the point, his late<br />

painting Sun in an Empty Room<br />

(1963) is a pure study of sunlight.<br />

Most of Hopper's figure paintings<br />

focus on the subtle interaction of<br />

human beings with their<br />

environment—carried out with solo<br />

figures, couples, or groups. His<br />

primary emotional themes are<br />

solitude, loneliness, regret,<br />

boredom, and resignation. He<br />

expresses the emotions in various<br />

environments, including the office,<br />

in public places, in apartments, on<br />

the road, or on vacation. As if he<br />

were creating stills for a movie or<br />

tableaux in a play, Hopper<br />

positioned his characters as if they<br />

were captured just before or just<br />

after the climax of a scene.<br />

Hopper's solitary figures are mostly<br />

women—dressed, semi-clad, and<br />

nude—often reading or looking out<br />

a window, or in the workplace. In<br />

the early 1920s, Hopper painted his<br />

first such images Girl at Sewing<br />

Machine (1921), New York Interior<br />

(another woman sewing) (1921),<br />

and Moonlight Interior (a nude<br />

getting into bed) (1923). Automat<br />

(1927) and Hotel Room (1931),<br />

however, are more representative<br />

of his mature style, emphasizing<br />

the solitude more overtly.

As Hopper scholar, Gail Levin,<br />

wrote of Hotel Room:<br />

The spare vertical and diagonal<br />

bands of color and sharp electric<br />

shadows create a concise and<br />

intense drama in the<br />

night...Combining poignant<br />

subject matter with such a<br />

powerful formal arrangement,<br />

Hopper's composition is pure<br />

enough to approach an almost<br />

abstract sensibility, yet layered<br />

with a poetic meaning for the<br />

observer.<br />

Hopper's Room in New York (1932)<br />

and Cape Cod Evening (1939) are<br />

prime examples of his "couple"<br />

paintings. In the first, a young<br />

couple appear alienated and<br />

uncommunicative—he reading the<br />

newspaper while she idles by the<br />

piano. The viewer takes on the role<br />

of a voyeur, as if looking with a<br />

telescope through the window of<br />

the apartment to spy on the<br />

couple's lack of intimacy. In the<br />

latter painting, an older couple<br />

with little to say to each other, are<br />

playing with their dog, whose own<br />

attention is drawn away from his<br />

masters.Hopper takes the couple<br />

theme to a more ambitious level<br />

with Excursion into Philosophy<br />

(1959). A<br />

middle-aged man sits dejectedly on<br />

the edge of a bed. Beside him lies<br />

an open book and a partially clad<br />

woman. A shaft of light illuminates<br />

the floor in front of him. Jo Hopper<br />

noted in their log book, "he open<br />

book is Plato, reread too late".<br />

Levin interprets the painting:<br />

Plato's philosopher, in search of the<br />

real and the true, must turn away<br />

from this transitory realm and<br />

contemplate the eternal Forms and<br />

Ideas. The pensive man in Hopper's<br />

painting is positioned between the<br />

lure of the earthly domain, figured<br />

by the woman, and the call of the<br />

higher spiritual domain,<br />

represented by the ethereal<br />

lightfall. The pain of thinking about<br />

this choice and its consequences,<br />

after reading Plato all night, is<br />

evident. He is paralysed by the<br />

fervent inner labour of the<br />

melancholic.<br />

In Office at Night (1940), another<br />

"couple" painting, Hopper creates a<br />

psychological puzzle. The painting<br />

shows a man focusing on his work<br />

papers, while nearby his attractive<br />

female secretary pulls a file.

Several studies for the painting<br />

show how Hopper experimented<br />

with the positioning of the two<br />

figures, perhaps to heighten the<br />

eroticism and the tension. Hopper<br />

presents the viewer with the<br />

possibilities that the man is either<br />

truly uninterested in the woman's<br />

appeal or that he is working hard<br />

to ignore her. Another interesting<br />

aspect of the painting is how<br />

Hopper employs three light<br />

sources,from a desk lamp,<br />

through a window and indirect<br />

light from above. Hopper went on<br />

to make several "office"<br />

pictures, but no others with a<br />

sensual undercurrent.<br />

The best-known of Hopper's<br />

paintings, Nighthawks (1942), is<br />

one of his paintings of groups. It<br />

shows customers sitting at the<br />

counter of an all-night diner.<br />

The shapes and diagonals are<br />

carefully constructed. The<br />

viewpoint is cinematic—from the<br />

sidewalk, as if the viewer were<br />

approaching the restaurant. The<br />

diner's harsh electric light sets it<br />

apart from the dark night outside,<br />

enhancing the mood and subtle<br />

emotion.As in many Hopper<br />

paintings, the interaction is<br />

minimal. The restaurant depicted<br />

was inspired by one in Greenwich<br />

Village. Both Hopper and his wife<br />

posed for the figures, and Jo<br />

Hopper gave the painting its title.<br />

The inspiration for the picture may<br />

have come from Ernest<br />

Hemingway's short story "The<br />

Killers", which Hopper greatly<br />

admired, or from the more<br />

philosophical "A Clean, Well-<br />

Lighted Place".<br />

In keeping with the title of his<br />

painting, Hopper later said,<br />

Nighthawks has more to do with<br />

the possibility of predators in the<br />

night than with loneliness.<br />

His second most recognizable<br />

painting after Nighthawks is<br />

another urban painting, Early<br />

Sunday Morning (originally called<br />

Seventh Avenue Shops), which<br />

shows an empty street scene in<br />

sharp side light, with a fire hydrant<br />

and a barber pole as stand-ins for<br />

human figures. Originally Hopper<br />

intended to put figures in the<br />

upstairs windows but left them<br />

empty to heighten the feeling of<br />

desolation.

Hopper's rural New England<br />

scenes, such as Gas (1940), are no<br />

less meaningful. Gas represents "a<br />

different, equally clean,<br />

well-lighted refuge...open for<br />

those in need as they navigate<br />

the night, traveling their own<br />

miles to go before they sleep.<br />

" The work presents a fusion of<br />

several<br />

Hopper themes: the solitary<br />

figure, the melancholy of dusk,<br />

and the lonely road.<br />

accompaniment of the musicians<br />

in the pit.<br />

Girlie Show was inspired by<br />

Hopper's visit to a burlesque show<br />

a few days earlier. Hopper's wife, as<br />

usual, posed for him for the<br />

painting, and noted in her diary,<br />

"Ed beginning a new canvas—a<br />

burlesque queen doing a strip<br />

tease—and I posing without a stitch<br />

on in front of the stove—nothing<br />

but high heels in a lottery dance<br />

pose."<br />

Hopper approaches Surrealism<br />

with Rooms by the Sea (1951),<br />

where an open door gives a view<br />

of the ocean, without an apparent<br />

ladder or steps and no indication<br />

of a beach.<br />

After his student years, Hopper's<br />

nudes were all women. Unlike<br />

past artists who painted the<br />

female nude to glorify the female<br />

form and to highlight female<br />

eroticism, Hopper's nudes are<br />

solitary women who are<br />

psychologically exposed.One<br />

audacious exception is Girlie Show<br />

(1941), where a red-headed striptease<br />

queen strides confidently<br />

across a stage to the<br />

Hopper's portraits and selfportraits<br />

were relatively few after<br />

his student years.Hopper did<br />

produce a commissioned "portrait"<br />

of a house, The Mac<strong>Art</strong>hurs' Home<br />

(1939), where he faithfully details<br />

the Victorian architecture of the<br />

home of actress Helen Hayes. She<br />

reported later, "I guess I never met<br />

a more misanthropic, grumpy<br />

individual in my life." Hopper<br />

grumbled throughout the project<br />

and never again accepted a<br />

commission.Hopper also painted<br />

Portrait of Orleans (1950), a<br />

"portrait" of the Cape Cod town<br />

from its main street.

Though very interested in the<br />

American Civil War and Mathew<br />

Brady's battlefield photographs,<br />

Hopper made only two historical<br />

paintings. Both depicted soldiers on<br />

their way to Gettysburg.Also rare<br />

among his themes are paintings<br />

showing action. The best example<br />

of an action painting is Bridle Path<br />

(1939), but Hopper's struggle with<br />

the proper anatomy of the horses<br />

may have discouraged him from<br />

similar attempts.<br />

meaning can be added to a painting<br />

by its title, but the titles of<br />

Hopper's paintings were sometimes<br />

chosen by others, or were selected<br />

by Hopper and his wife in a way<br />

that makes it unclear whether they<br />

have any real connection with the<br />

artist's meaning. For example,<br />

Hopper once told an interviewer<br />

that he was "fond of Early Sunday<br />

Morning... but it wasn't necessarily<br />

Sunday. That word was tacked on<br />

later by someone else."<br />

Hopper's final oil painting, Two<br />

Comedians (1966), painted one<br />

year before his death, focuses on<br />

his love of the theater. Two French<br />

pantomime actors, one male and<br />

one female, both dressed in bright<br />

white costumes, take their bow in<br />

front of a darkened stage. Jo<br />

Hopper confirmed that her<br />

husband intended the figures to<br />

suggest their taking their life's last<br />

bows together as husband and<br />

wife.<br />

Hopper's paintings have often<br />

been seen by others as having a<br />

narrative or thematic content that<br />

the artist may not have intended.<br />

Much<br />

The tendency to read thematic or<br />

narrative content into Hopper's<br />

paintings, that Hopper had not<br />

intended, extended even to his<br />

wife. When Jo Hopper commented<br />

on the figure in Cape Cod Morning<br />

"It's a woman looking out to see if<br />

the weather's good enough to hang<br />

out her wash," Hopper retorted,<br />

"Did I say that? You're making it<br />

Norman Rockwell. From my point<br />

of view she's just looking out the<br />

window."Another example of the<br />

same phenomenon is recorded in a<br />

1948 article in Time:<br />

Hopper's Summer Evening, a young<br />

couple talking in the harsh light of a<br />

cottage porch

is inescapably romantic, but Hopper was hurt by one critic's suggestion<br />

that it would do for an illustration in "any woman's magazine." Hopper<br />

had the painting in the back of his head "for 20 years and I never<br />

thought of putting the figures in until I actually started last summer.<br />

Why any art director would tear the picture apart. The figures were not<br />

what interested me; it was the light streaming down, and the night all<br />

around."

Nadim Karam born 1957is a<br />

multidisciplinary Lebanese artist,<br />

painter, sculptor and architect who<br />

fuses his artistic output of<br />

sculpture, painting, drawing with<br />

his background in architecture to<br />

create large-scale urban art<br />

projects in different cities of the<br />

world. He uses his vocabulary of<br />

forms in urban settings to narrate<br />

stories and evoke collective<br />

memory with a very particular<br />

whimsical, often absurdist<br />

approach; seeking to 'create<br />

moments of dreams' in different<br />

cities of the world.<br />

Early life and education<br />

Nadim Karam grew up in Beirut.<br />

He received a Bachelor of<br />

Architecture from the American<br />

University of Beirut in 1982, at the<br />

height of the Lebanese civil<br />

war,and left the same year to<br />

study in Japan on a Monbusho<br />

scholarship. At the University of<br />

Tokyo he developed an interest in<br />

Japanese philosophy of space,<br />

which he studied under Hiroshi<br />

Hara, and was also taught by<br />

Fumihiko Maki and Tadao Ando.<br />

He created several solo art<br />

performances and exhibitions in<br />

Tokyo while completing master and<br />

doctorate degrees in architecture.<br />

Teaching<br />

Nadim Karam taught at the<br />

Shibaura Institute of Technology in<br />

Tokyo in 1992 with Riichi Miyake<br />

and then returned to Beirut to<br />

create his experimental group,<br />

Atelier Hapsitus. The name, derived<br />

from the combination of Hap<br />

(happenings) and Situs (situations),<br />

comes from Karam's enjoyment of<br />

the fact that the encounter of these<br />

two factors often gives rise to the<br />

unexpected. He taught<br />

architectural design at the<br />

American University of Beirut<br />

(1993-5, 2003–4), and was Dean of<br />

the Faculty of Architecture, <strong>Art</strong> and<br />

Design at Notre Dame University in<br />

Lebanon from 2000–2003. He cochaired<br />

in 2002 the UN/New York<br />

University conference in London for<br />

the reconstruction of Kabul and<br />

was selected as the curator for<br />

Lebanon by the first Rotterdam<br />

Biennale.From 2006–7 he served<br />

on the Moutamarat Design Board<br />

for Dubai and regularly gives<br />

lectures at universities and<br />

conferences worldwide.<br />

20

Urban art projects<br />

With Atelier Hapsitus, the pluridisciplinary<br />

company he founded<br />

in Beirut, he created large-scale<br />

urban art projects in different<br />

cities including Beirut, Prague,<br />

London, Tokyo, Nara and<br />

Melbourne. His project for<br />

Prague's Manes Bridge in the<br />

spring of 1997 was both a<br />

commemoration of the city's postcommunist<br />

liberalization and an<br />

echo of its history, with the<br />

placement of his works in parallel<br />

to the baroque sculptures on the<br />

Charles Bridge. The post-civil war<br />

1997–2000 itinerant urban art<br />

project he created for central<br />

Beirut was one of five worldwide<br />

selected by the Van Alen Institute<br />

in New York in 2002 to highlight<br />

the role they played in the<br />

rejuvenation of city life and<br />

morale after a disaster. In Japan,<br />

'The Three flowers of Jitchu'<br />

realized at Tōdai-ji Temple in Nara<br />

in 2004, was a temporary<br />

installation commemorating the<br />

achievements of a Middle Eastern<br />

monk, Jitchu, whose performance<br />

is still enacted yearly since the<br />

year 752 in the temple he<br />

designed for it. Karam's project<br />

took 20 years to gain acceptance<br />

from the Tōdai-ji Temple<br />

authorities. His 2006 Victoria State<br />

commission'The Travellers' a<br />

permanent art installation of ten<br />

sculptures which travel across<br />

Melbourne's Sandridge Bridge<br />

three times daily, tells the story of<br />

Australian immigrants and creates<br />

an urban clock in the city.<br />

Selected public art installations<br />

2017 Trio Elephants- Lovers’ Park,<br />

Yerevan, Armenia<br />

2017 Wheels of Innovation- Nissan<br />

Headquarters, Tokyo, Japan<br />

2016 Stretching Thoughts:<br />

Shepherd and Thinker- UWC<br />

Atlantic College, Wales, UK<br />

2014 Wishing Flower- Zaha Hadid's<br />

D’Leedon residential project,<br />

Leedon Heights, Singapor<br />

Architectural work<br />

Nadim Karam is mainly known for<br />

his conceptual work, like 'Hilarious<br />

Beirut', the 1993 post-war antiestablishment<br />

project for the<br />

reconstruction of Beirut city centre,<br />

and 'The Cloud"a huge public<br />

garden resembling a raincloud that<br />

stands at 250m above ground..

Inspired by the city of Dubai, it<br />

proposes a visual and social<br />

alternative to the exclusivity of<br />

the skyscrapers in Gulf cities.<br />

Karam's signature un-built<br />

projects include the 'Net Bridge' a<br />

pedestrian<br />

bridge conceived as a gateway to<br />

Beirut city centre from the marina<br />

with five lanes that playfully<br />

intersect and interweave.<br />

Similarly, his winning design of a<br />

competition<br />

for the BLC Bank headquartersfor<br />

Beirut features the new<br />

headquarters straddling the old.<br />

Karam collaborates closely with<br />

Arup Engineers in London, who<br />

give structural and technical<br />

reality to his most unusual ideas.<br />

Ongoing projects<br />

The Dialogue of the Hills is an<br />

urban art project conceived to<br />

invigorate the historic core of<br />

Amman through a series of public<br />

gardens and sculpture for each hill<br />

community. The sculptures are<br />

designed to create a dialogue with<br />

the others on the surrounding hills<br />

of the city, physically and visually<br />

linking diverse socio-economic<br />

communities. The Wheels of<br />

Chicago is a project inspired by the<br />

city where the Ferris wheel was<br />

invented. An iconic project for the<br />

city shoreline, through several<br />

wheels, symbolizes the different<br />

city communities and harnesses sea<br />

breezes to provide energy for the<br />

surrounding parklands

http://www.aziz-anzabi.com