Times of the Islands Summer 2020

Presents the "soul of the Turks & Caicos Islands" with in-depth features about local people, culture, history, environment, businesses, resorts, restaurants and activities.

Presents the "soul of the Turks & Caicos Islands" with in-depth features about local people, culture, history, environment, businesses, resorts, restaurants and activities.

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Key West quail-doves in North Caicos unequivocally<br />

object to people and our preposterous noise—<strong>the</strong>ir tolerance<br />

is so low that I’ve met people who have lived in Kew<br />

Settlement <strong>the</strong>ir entire lives and have never seen one. But<br />

since that day, this bird has made its presence in <strong>the</strong> yard<br />

a habit. Without cars rumbling by and with considerably<br />

less noise, it exposed itself from its clandestine life on<br />

<strong>the</strong> dark forest floor each late afternoon. Then it brought<br />

a friend. The pair struts about <strong>the</strong> now all-but-abandoned<br />

back road throughout <strong>the</strong> day. They’re still difficult to<br />

photograph, but I’ve at least captured one on my camera<br />

that is identifiable.<br />

But I’m not <strong>the</strong> only one with photographic pro<strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>of</strong> this natural takeover. In late May, photos and videos<br />

appeared on social media <strong>of</strong> one <strong>of</strong> my familiar<br />

haunts with a nostalgic twist. Twenty years ago, I lived<br />

in Bambarra Settlement, before <strong>the</strong> causeway linked <strong>the</strong><br />

islands <strong>of</strong> North and Middle Caicos and before <strong>the</strong> roads<br />

were paved. Day trippers were so rare <strong>the</strong>re was only one<br />

occasionally-functional rental car on <strong>the</strong> island.<br />

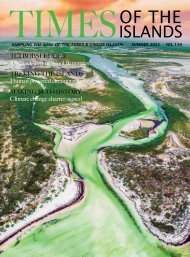

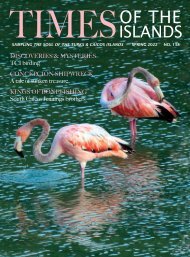

Bambarra Beach, with its expansive sandbar jutting<br />

half a mile towards Pelican Cay, was only ever peopled<br />

by <strong>the</strong> rare fisherman or rarer winter villa visitor. My peanut-butter-coloured<br />

potcake usually accompanied me,<br />

and unfortunately that’s why I never got to see <strong>the</strong> flamingos<br />

up close.<br />

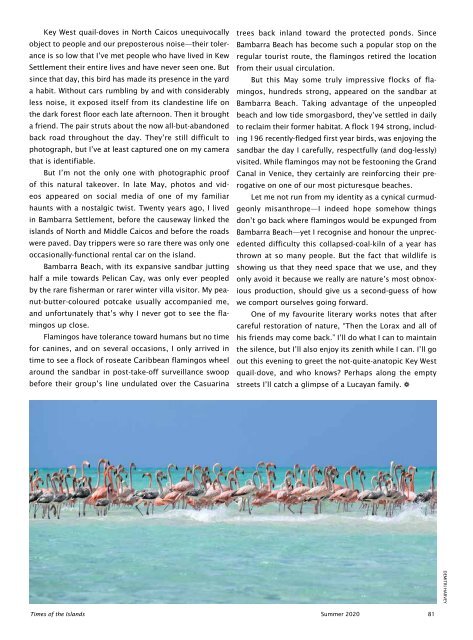

Flamingos have tolerance toward humans but no time<br />

for canines, and on several occasions, I only arrived in<br />

time to see a flock <strong>of</strong> roseate Caribbean flamingos wheel<br />

around <strong>the</strong> sandbar in post-take-<strong>of</strong>f surveillance swoop<br />

before <strong>the</strong>ir group’s line undulated over <strong>the</strong> Casuarina<br />

trees back inland toward <strong>the</strong> protected ponds. Since<br />

Bambarra Beach has become such a popular stop on <strong>the</strong><br />

regular tourist route, <strong>the</strong> flamingos retired <strong>the</strong> location<br />

from <strong>the</strong>ir usual circulation.<br />

But this May some truly impressive flocks <strong>of</strong> flamingos,<br />

hundreds strong, appeared on <strong>the</strong> sandbar at<br />

Bambarra Beach. Taking advantage <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> unpeopled<br />

beach and low tide smorgasbord, <strong>the</strong>y’ve settled in daily<br />

to reclaim <strong>the</strong>ir former habitat. A flock 194 strong, including<br />

196 recently-fledged first year birds, was enjoying <strong>the</strong><br />

sandbar <strong>the</strong> day I carefully, respectfully (and dog-lessly)<br />

visited. While flamingos may not be festooning <strong>the</strong> Grand<br />

Canal in Venice, <strong>the</strong>y certainly are reinforcing <strong>the</strong>ir prerogative<br />

on one <strong>of</strong> our most picturesque beaches.<br />

Let me not run from my identity as a cynical curmudgeonly<br />

misanthrope—I indeed hope somehow things<br />

don’t go back where flamingos would be expunged from<br />

Bambarra Beach—yet I recognise and honour <strong>the</strong> unprecedented<br />

difficulty this collapsed-coal-kiln <strong>of</strong> a year has<br />

thrown at so many people. But <strong>the</strong> fact that wildlife is<br />

showing us that <strong>the</strong>y need space that we use, and <strong>the</strong>y<br />

only avoid it because we really are nature’s most obnoxious<br />

production, should give us a second-guess <strong>of</strong> how<br />

we comport ourselves going forward.<br />

One <strong>of</strong> my favourite literary works notes that after<br />

careful restoration <strong>of</strong> nature, “Then <strong>the</strong> Lorax and all <strong>of</strong><br />

his friends may come back.” I’ll do what I can to maintain<br />

<strong>the</strong> silence, but I’ll also enjoy its zenith while I can. I’ll go<br />

out this evening to greet <strong>the</strong> not-quite-anatopic Key West<br />

quail-dove, and who knows? Perhaps along <strong>the</strong> empty<br />

streets I’ll catch a glimpse <strong>of</strong> a Lucayan family. a<br />

DEMITRI HARVEY<br />

<strong>Times</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Islands</strong> <strong>Summer</strong> <strong>2020</strong> 81