The Queen's College Newsletter - Trinity Term 2020

This issue of our annual Newsletter looks at some of the COVID-19-related research carried out by members and the impact of lockdown on the College community. There is an interview with translator and Old Member, Nicolas Pasternak Slater, and articles on consent (by our Junior Research Fellow in Philosophy); hydrogen as an energy source; and the designs for rebuilding Queen's that were drawn up by Nicholas Hawksmoor in the eighteenth century.

This issue of our annual Newsletter looks at some of the COVID-19-related research carried out by members and the impact of lockdown on the College community. There is an interview with translator and Old Member, Nicolas Pasternak Slater, and articles on consent (by our Junior Research Fellow in Philosophy); hydrogen as an energy source; and the designs for rebuilding Queen's that were drawn up by Nicholas Hawksmoor in the eighteenth century.

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

<strong>Newsletter</strong><br />

Issue thirty-TWO trinity <strong>Term</strong> <strong>2020</strong> 07/20<br />

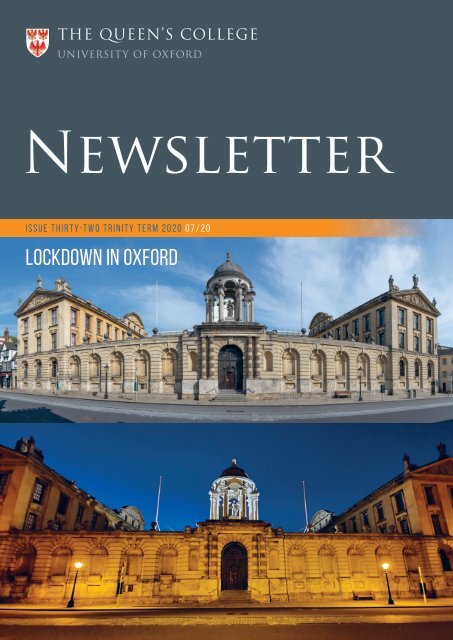

LOCKDOWN IN OXFORD

THE QUEEN’S COLLEGE<br />

Contents<br />

pages 2-3<br />

Letter from the provost<br />

Pages 4-5<br />

QUEEN’S RESPONSE TO CORONAVIRUS<br />

Pages 6-7 ADAPTING: TRINITY <strong>2020</strong><br />

pages 8-10<br />

NEWS IN BRIEF<br />

Page 11<br />

Consent or Why Saying is (not) Doing<br />

pages 12–13 AN INTERVIEW WITH NICOLAS PASTERNAK SLATER<br />

pages 14<br />

Hydrogen as an Energy Source<br />

Page 15<br />

HAWKSMOOR DRAWINGS<br />

back cover<br />

calendar<br />

PAGE 7<br />

Cover photographs: an unusually deserted High Street, in April <strong>2020</strong> © David Olds (IT Manager)<br />

and by night, in May <strong>2020</strong> © Suzanne Engelen (DPhil in Biomedical and Clinical Sciences, 2019).<br />

Letter from the Provost<br />

Dr Claire Craig<br />

To say the year has been surprising would be, of course, an<br />

understatement of the most British kind.<br />

As a newcomer to Queen’s, back at the start of Michaelmas<br />

term, I was going through a series of “firsts” like any other<br />

Fresher. First meal in Hall, first time in Chapel in the Provost’s<br />

stall with its red velvet cushions. First Governing Body meeting<br />

and first set of Provost’s Handshakes, to meet the real Freshers.<br />

First Provost’s Academic Collections, to discuss progress with<br />

students and their tutors. First full suite of committee meetings<br />

(the main committees are every Wednesday during term, for<br />

those who are interested!). First Conference of <strong>College</strong>s to<br />

meet the other Heads of House and realise<br />

the full variety of college models and<br />

characters. First handwritten letters from<br />

Old Members around the world, and first<br />

personal accounts of the <strong>College</strong> from the<br />

1940s onwards. First <strong>College</strong> guest in the<br />

Lodgings (the Visitor, the then Archbishop of<br />

York, Dr John Sentamu and his wonderful<br />

wife Margaret). First Boar’s Head Gaudy,<br />

Loving Cup, and first Baked Alaska pudding.<br />

First realisation that I needed to exercise<br />

strong self-discipline around the cellar and<br />

the desserts.<br />

<strong>The</strong>n just as things were becoming familiar,<br />

some of them changed completely. As many<br />

of you will recall or experienced firsthand,<br />

the <strong>College</strong> was initially affected by<br />

the pandemic during Hilary term. Over a<br />

period of days in March, staff, students and Fellows faced the<br />

challenges and fears of the onset of COVID-19. As I reported<br />

then, Queen’s had a confirmed case. Like the rest of the<br />

world we were scrambling to respond and to adapt to each<br />

Dr John Sentamu in the <strong>College</strong> Chapel<br />

new development and to the evolving government advice.<br />

Our approach, then as now, was to focus on what Queen’s is<br />

here for: teaching, learning and researching – and to be safe.<br />

We have tried to do that in ways that have been characteristic<br />

of the best of Queen’s throughout time: resilient, brave and<br />

kind, and I would like to pay particular tribute to the current<br />

generations at the <strong>College</strong> for the ways in which they have<br />

responded throughout.<br />

<strong>The</strong> undergraduates completed Hilary term and, from the<br />

Easter vacation onwards, the main site has been closed.<br />

Many of the scouts, kitchen and other staff are on furlough,<br />

and the High Street and Queen’s Lane are<br />

eerily deserted. In homes across the UK<br />

and abroad, however, tutors and lecturers<br />

worked incredibly hard to move teaching<br />

and assessment online for <strong>Trinity</strong> term.<br />

<strong>The</strong>y achieved this feat and the first ever<br />

cohort of students will graduate virtually<br />

this summer. It has been very difficult for<br />

many, in practical and personal ways. <strong>The</strong><br />

uncertainty and new challenges will continue<br />

during the Long Vacation as Queen’s and<br />

the rest of Oxford plan for a wide range of<br />

scenarios for Michaelmas <strong>2020</strong> and beyond.<br />

We continue determined to provide the<br />

best possible teaching and learning, with<br />

tutorials – and the contact between students<br />

and world-leading academics – as the core<br />

of what makes Oxford special.<br />

Queen’s is a strongly independent place, which is part of what<br />

helps it provide space to think and time to learn. Its willingness<br />

to stick to the course it believes is right both for current and<br />

future generations is also reflected in its financial prudence.<br />

2

www.queens.ox.ac.uk<br />

Photo © David Fisher<br />

That prudence has in turn built solid foundations that should<br />

help the <strong>College</strong> weather the next few months and years but,<br />

like everyone else, we cannot avoid the difficult economic<br />

consequences of the pandemic and we do not know what<br />

will be asked of us.<br />

During my time in the Civil Service, I worked both on<br />

emergencies – supporting SAGE 1 , which was much less well<br />

known in the UK then than it is now – and on informing policies<br />

for the very long term in areas such as climate change, energy<br />

and Artificial Intelligence. Time and again studies of the histories<br />

of major change reinforce the notion that disruption often<br />

provides opportunity. We need to build that knowledge into our<br />

anticipations of the future. A small immediate illustration of the<br />

opportunities is a virtual lunch I held recently with a group of<br />

women who have played a large part in establishing the Queen’s<br />

Women’s Network, founded as part of the celebration of the<br />

40th anniversary of women undergraduates first matriculating<br />

at Queen’s. <strong>The</strong> lunch included one person in Stirling and one<br />

in Luxembourg. Neither would have attended if it had been,<br />

as originally planned, in the Lodgings (lovely as they are with<br />

the scent of roses coming in from the gardens in the summer).<br />

<strong>The</strong> companionship and the conversation were the richer for<br />

their presence.<br />

That lunch highlighted how we are only just beginning fully to<br />

let ourselves explore the new opportunities. Many changes are<br />

being forced on us, but these changes sometimes open up new<br />

spaces, creating new choices to build for the future. One of my<br />

ambitions for the <strong>College</strong> is to make it slightly more “porous”:<br />

1<br />

SAGE is the UK Government’s Scientific Advisory Group in Emergencies,<br />

which has been playing a significant role in informing policy on COVID-19<br />

to do more to support its exceptional people, and to increase<br />

the flow of ideas and the range of opportunities for people to<br />

meet, across disciplines and across generations. Moving some<br />

of what we do online – drawing more people in, changing<br />

formats and creating new futures, histories and records will,<br />

over time, be one of the ways of doing that. And when we<br />

are able to gather again for gaudies and garden parties, for<br />

tutorials and symposia, they will be richer because they will be<br />

embedded in these wider practices and networks.<br />

Finally, I do not think this account of the year would be complete<br />

without a mention of the late Dr Bill Frankland MBE, DM, FRCP,<br />

Queen’s Old Member (Physiological Sciences, 1930) and<br />

Honorary Fellow who died, aged 108, in April. Bill was attending<br />

Queen’s Old Members events in 2019, and publishing academic<br />

articles right up to the end of his life. His legacy includes the<br />

introduction of the pollen count, which helps asthma sufferers<br />

and others stay healthier.<br />

Many of today’s academics are working on COVID-19-<br />

related matters, from ventilator and vaccine technologies,<br />

to using economic history to inform debate about the longterm<br />

economic impacts. For them, and for all of the Queen’s<br />

communities, it has been a surprising year. Next year will<br />

undoubtedly be a surprising one for us all too and throughout it<br />

the <strong>College</strong> will remain a place – physical and virtual – to think,<br />

learn and to meet friends.<br />

3

THE QUEEN’S COLLEGE<br />

Queen’s Response to Coronavirus<br />

Read more on our website: www.queens.ox.ac.uk/news<br />

Disabling the Protein involved in<br />

Coronavirus<br />

Tristan Johnston-Wood (MSc in <strong>The</strong>oretical and Computational<br />

Chemistry, 2018; current DPhil in Chemistry) models proteins<br />

using computational methods and has, since March, been<br />

focusing on the main protein involved in SARS-CoV-2, named<br />

Main Protease.<br />

Mathematical Modelling to Control<br />

the COVID-19 Spread<br />

Dr Jasmina Panovska-Griffiths (Maths, 1996 & DPhil in Maths),<br />

Lecturer in Applied Mathematics, applies mathematical models<br />

to COVID-19 transmission. Her focus is on better understanding<br />

the role of asymptomatic carriers in spreading the infection and<br />

modelling different lockdown relaxation scenarios. Jasmina is<br />

collaborating with the Wolfson Centre for Mathematical Biology at<br />

Oxford and also contributes her expertise to working groups that<br />

advise policy decision makers on how to guide us safely out of<br />

this pandemic.<br />

‘This protein has the ability to cut up other proteins which<br />

it then uses in its mechanism for hijacking a host’s cells,’<br />

explained Tristan. ‘<strong>The</strong>re has therefore been great interest in<br />

developing an anti-viral drug to target this protein and inhibit<br />

its function. My research group’s role has mainly been to<br />

understand how it binds to other proteins. This understanding<br />

will hopefully help other researchers in choosing or developing<br />

anti-viral drugs that will bind to the protein and stop it from<br />

performing its job.’<br />

Since the emergence of coronavirus, Jasmina has written a<br />

number of scientific papers, has been regularly featured in<br />

the media and been commissioned to write several articles<br />

for <strong>The</strong> Conversation and the BMJ on this subject.<br />

COVID-19 Drug Trial<br />

Prof. Peter Robbins (Fellow in Medicine)<br />

is Lead Researcher on a clinical drug<br />

trial running as a collaboration between<br />

academics from several different<br />

Oxford departments and NHS hospital<br />

consultants, funded by LifeArc. <strong>The</strong> trial<br />

will test an old drug first developed in<br />

France called almitrine bismesylate, which<br />

could raise oxygen levels in the blood in<br />

COVID-19 patients in order to improve<br />

their chances of recovery.<br />

‘We know that almitrine can increase<br />

oxygen levels in patients with acute<br />

respiratory distress syndrome by<br />

constricting the blood vessels in regions<br />

4<br />

of the lung where the oxygen is low,’<br />

said Peter. ‘If almitrine can add to the<br />

overall effectiveness of respiratory<br />

support, then the hope is that clinicians<br />

will need to mechanically ventilate fewer<br />

COVID-19 patients.<br />

‘People can recover from COVID-19<br />

by fighting off the virus with the body’s<br />

normal defence mechanisms. But if the<br />

lung becomes so damaged that blood<br />

just doesn’t pick up enough oxygen, then<br />

the body never gets the chance to finish<br />

the job and the patient dies from the low<br />

level of oxygen. So, what we are really<br />

trying to do with supportive therapy is help<br />

the patient to continue to function whilst<br />

their body fights off the infection in the<br />

normal way.’<br />

Cartoon © Keith Dorrington

www.queens.ox.ac.uk<br />

<strong>The</strong>re is a palpable absence of sub fusc and<br />

celebration on the streets of Oxford this <strong>Trinity</strong> term.<br />

<strong>College</strong>s are empty, exams are online, and graduations<br />

are cancelled.<br />

For us, the final-year medical students from Queen’s,<br />

being part of the ‘Class of COVID’ has meant<br />

abandoned placements, early graduation and starting<br />

on the wards a few months earlier than planned. While<br />

it has been an invaluable learning opportunity and<br />

a great privilege to help during this unprecedented<br />

scenario, becoming a doctor has brought its<br />

challenges. We each wanted to give a little insight into<br />

an on-the-ward view of the coronavirus pandemic.<br />

“<br />

Final-year medical students usually<br />

complete their exams in January, followed<br />

by a period of clinical assistantship in<br />

Oxford and elective medical placements<br />

overseas. My plan was to join a hospital<br />

surgical team in Blantyre, Malawi – but<br />

from mid-February, I was having to<br />

reconsider. Fast-forward one month, I was<br />

one of 20 final-year medical students<br />

volunteering in the A&E department of<br />

the John Radcliffe Hospital as it was<br />

gearing up for the peak of the pandemic.<br />

I felt privileged to be able to help with<br />

triaging patients into respiratory and nonrespiratory<br />

areas, working as a healthcare<br />

assistant and a receptionist.<br />

At the beginning of April, I completed<br />

my medical degree. I must be one<br />

of the very few people to have ever<br />

graduated in their sleep – a cheerful email<br />

with congratulations from our Director<br />

of Clinical Studies landed in my inbox<br />

not long after I completed a night shift in<br />

the hospital.<br />

In May, I became an Interim Foundation<br />

Doctor (or FiY1) in the Geriatrics<br />

Department of Stoke Mandeville Hospital.<br />

While Malawi would’ve been an incredible<br />

experience, so was (and is) being part of<br />

the NHS in this unique situation.<br />

Mark Zorman<br />

“<br />

Initially, I spent time in the Community<br />

COVID Hub, essentially a drive-through<br />

GP practice for suspected COVID<br />

patients, which gave me an insight into<br />

the rapid restructuring of primary care to<br />

cope with the pandemic. I then began<br />

work in the Complex Medicine Unit in the<br />

John Radcliffe. I was initially surprised<br />

by how quiet the hospital seemed but<br />

work soon stepped up and with it came<br />

a steep learning curve. It is incredibly<br />

rewarding to work alongside a great<br />

team to overcome the barriers created<br />

by COVID. Communicating via telephone<br />

or video calls can make a world of<br />

difference for our patients, and reducing<br />

the distress for them and their relatives is<br />

hugely meaningful.<br />

Molly Nichols<br />

“<br />

I volunteered for six weeks in<br />

Cardiology at the John Radcliffe,<br />

helping with ward jobs, and connecting<br />

COVID-19 patients to their families via<br />

video calls. <strong>The</strong> team in Oxford were<br />

incredibly supportive as we received our<br />

email graduation congratulations and<br />

transitioned from medical students to<br />

doctors. I’m now working in Cardiology at<br />

Wycombe Hospital. I’m lucky that I was<br />

given a job in the same specialty to carry<br />

skills and knowledge to my new hospital,<br />

and look forward to continuing my<br />

development as a (very!) junior doctor.<br />

Emma Roberts<br />

“<br />

Since graduating early, I’ve become<br />

an FiY1 in Geriatrics at the John Radcliffe,<br />

working with older non-COVID patients.<br />

I quickly realised how different the job of<br />

doctor is to being a student. Though I feel<br />

like I’ve been somewhat “thrown in”, it has<br />

been such a valuable experience and I feel<br />

my confidence growing with every task<br />

I complete.<br />

Celebrations after second-year exams. Photo © Molly Nichols<br />

It’s strange to think that right now I should<br />

be in Malaysia after a month in New<br />

Zealand – part of my medical elective that<br />

never happened. Even as late as March,<br />

I assumed that was my plan, and had<br />

started packing. However, being able to<br />

work as a doctor and lend an extra hand in<br />

this crisis has been very rewarding and I’m<br />

glad to have had this experience.<br />

Sarah Ahmed<br />

“<br />

In February, I was in Malawi, listening<br />

to a hospital Public Health Director giving<br />

a lecture on coronavirus preparedness.<br />

I was much more interested in exploring<br />

Malawi, and learning about exciting<br />

tropical diseases, than concentrating on<br />

the spread of COVID. I naively assumed it<br />

wouldn’t affect my medical training.<br />

I now work in General Medicine at Stoke<br />

Mandeville Hospital, seeing adults with<br />

COVID and with other medical problems.<br />

Having the title of ‘Dr’ has been daunting<br />

but exciting. I am really grateful to all of<br />

our tutors at Queen’s for their bedside<br />

teaching, which I didn’t expect to be<br />

putting to use so quickly, and particularly<br />

to Dr Sarah Millette, Assistant Clinical Tutor<br />

at Queen’s, for her ongoing support to all<br />

of us as we navigate the trials of being the<br />

most junior of doctors. Although it wasn’t<br />

what we were expecting when celebrating<br />

the end of our Finals in January, I think<br />

we’re all grateful to be able to support<br />

the national effort to combat this<br />

devastating disease.<br />

Zachary Tait<br />

5

THE QUEEN’S COLLEGE<br />

Adapting: <strong>Trinity</strong> <strong>2020</strong><br />

Small group, close, interactive teaching is the Oxford tutorial<br />

model. “Remoteness” and “social distancing” are pretty much its<br />

opposite. So remote learning – moving the whole of our teaching<br />

online – has been one of the largest challenges Queen’s has faced<br />

this term. It’s good to be able to relate how swiftly and flexibly the<br />

changes have been made. Hundreds of tutorials and classes have<br />

been using video-conferencing each week. <strong>The</strong> <strong>College</strong> Office<br />

arranged Collections to resemble the new “open book” system<br />

that applied in Finals this year. It has also been doing what it can<br />

to help students whose home environment isn’t suitable for study.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Library has been providing access to hard-to-obtain books<br />

online. Tutors like me have even been taking the opportunity to<br />

update their reading lists.<br />

It was very encouraging to see how everyone did their best to<br />

adapt. Things that are essential to tutorial teaching – ways to<br />

explain things, or to lead discussions – turn out to be do-able in<br />

new ways. Things that seemed incidental – the quick, unplanned<br />

exchanges when you bump into those you teach in Front Quad –<br />

turn out to be things you miss.<br />

In certain ways we are less close. It’s easy to imagine that<br />

everyone else is still there on site, and it is only we who are<br />

located remotely. Somehow, imagining the deserted buildings is<br />

a mental step too far. We have had to learn patience: not easy for<br />

some of us. Normally, it’s the sign of a good tutorial if everyone<br />

tries to speak at once. But the technology isn’t quite good enough<br />

yet to cope with the energy of so many people who all want to<br />

share their opinions at the same time. We have had to get used<br />

to webcams revealing more of our colleagues’ domestic lives,<br />

whether it is cats and children wandering plaintively into shot, or<br />

some startling home décor choices.<br />

So, it isn’t really Queen’s. How could it be, given who we are,<br />

and what we like to do? But, in other ways – especially in the<br />

inventiveness, the good humour, and the resourcefulness people<br />

have shown in coping with this dreadful change to our lives – it<br />

does feel familiar, and, in that sense, not remote at all.<br />

Dr Nicholas Owen, Fellow in Politics and Senior Tutor<br />

Here’s what some other people think...<br />

Lewis Wales, 1st year, DPhil in Inorganic Chemistry<br />

‘I’m in the Oxford Inorganic Chemistry for Future<br />

Manufacturing Centre, which means we started with<br />

six months of taught courses. Practical work will,<br />

hopefully, form the majority of my DPhil research, but<br />

the lab being shut has allowed me to learn some basic<br />

computational chemistry techniques which should aid<br />

my research in the long run. Thankfully, even though<br />

I’m back home, I can still connect to the University<br />

servers so have access to all the resources I need to<br />

keep (somewhat) productive.’<br />

Henry Gray, 3rd year, Chemistry<br />

‘Online tutorials have been surprisingly<br />

similar to normal tutorials, albeit with some<br />

Wi-Fi connection issues. I have found<br />

however, that these can often be used<br />

to one’s advantage to avoid answering a<br />

difficult question. A tactic quickly mastered<br />

by students and tutors alike. <strong>The</strong> thing I’m<br />

most missing about Oxford is definitely my<br />

own space, and not having to be around<br />

my family all the time.’<br />

Klara Zhao, 1st year, French and Linguistics<br />

‘Deprived of the golden afternoons of a classic <strong>Trinity</strong> term<br />

in Oxford, the pandemic has thrown us into an surreal world<br />

of misplaced pixels and buffering dialogues. Exams were<br />

cancelled, but at least this meant that we could learn for the<br />

sake of learning. <strong>The</strong> JCR are keeping everyone up to date<br />

with virtual meet-ups diluted to digital media. It seems that<br />

now, we can only rely to some extent on sharing photos and<br />

videos of the places<br />

where we find ourselves<br />

indefinitely in lockdown,<br />

in order to retain some<br />

sense of community.’<br />

Triya Chakravorty,<br />

1st year, Clinical Medicine<br />

(Second BM)<br />

‘First-year clinical students like<br />

myself are faced with a dilemma:<br />

our relatively limited clinical<br />

exposure restricts our ability to<br />

make a meaningful contribution on the wards, but we still feel<br />

a responsibility to contribute where we can. Currently, all clinical<br />

teaching is suspended. This is unfortunate, but unavoidable,<br />

given the unnecessary risk our presence would be on the wards.<br />

<strong>The</strong> whole world will be playing catch-up in the aftermath of the<br />

pandemic and, as a medical student, I will have to do the same.’<br />

6

www.queens.ox.ac.uk<br />

Tessa Shaw, Acting Librarian<br />

‘We were quick to adapt to lockdown and IT were fantastic in preparing us to be able to work<br />

from home. One of the team goes in to physically check on the collections once a week and<br />

carry out other duties. We gave ourselves the brief of identifying the stout lily pads, and then<br />

landing on them! Plans were drawn up to ensure that the service offer was manageable,<br />

sustainable and met expectations. We have facilitated access to e-resources, checked<br />

numerous reading lists and then edited them to include electronic links, and have also<br />

provided an on-demand scanning service. <strong>The</strong> opportunity to work more collaboratively with<br />

other college libraries and the Bodleian has been welcomed and it would be my hope that<br />

this is a model which is sustained and developed beyond the immediate times.<br />

‘It’s a team effort, there’s more work going on in the background. At the time of writing<br />

we meet once a day for a catch-up/are-you-doing-okay on MS Teams. Staff wellbeing is<br />

important at all times but even more so now. Topics range from frozen courgette flowers,<br />

Eurovision and the wonders of oatmeal, through to the details of copyright law – the latter is<br />

a bit like discussing your pension: really important but so dull, and often more confusing the<br />

more you think about it. Thanks to Sarah and Dom for being such agile lily pad jumpers!’<br />

Photo © David Fisher<br />

Prof. Owen Rees, Fellow in Music<br />

and Director of the Chapel Choir<br />

‘<strong>The</strong> Choir has felt the impact of the COVID crisis on the<br />

performing arts: very sadly, our planned concert and recording<br />

with the Academy of Ancient Music and this summer’s tour<br />

to Belgium – during which we were due to give the opening<br />

concert of a major music festival – have been postponed.<br />

Likewise, as churches closed their doors our Chapel has fallen<br />

musically silent for the first time in decades. But music-making<br />

and the social side of the Choir have moved online, with weekly<br />

“pub” Zoom meetings – we even managed our annual black-tie<br />

Choir dinner (pictured) – and “virtual choir” recordings.’<br />

Dr Lindsay Turnbull, Fellow in Plant Sciences<br />

‘I decided to make a series of videos about<br />

biology from my back garden when the<br />

lockdown started and I realised that the<br />

students wouldn’t be returning to Oxford.<br />

I thought the videos might replace the parts<br />

of the tutorial where I bring things in to show<br />

them, which they often enjoy. I’d never made<br />

videos before, but thought it would be a good time to learn<br />

something new. It’s also proved a useful way of providing material to<br />

replace our residential field course for first-years.’ Watch Lindsay’s<br />

Back Garden Biology series at bit.ly/backgardenbiology.<br />

Katharine Wiggell, Schools Liaison,<br />

Outreach and Recruitment Officer<br />

‘Being in lockdown has meant I’ve had<br />

the chance to try new things as part of<br />

our Outreach provision, from delivering<br />

admissions support sessions over<br />

Zoom, to researching educational<br />

podcasts and documentaries that<br />

might help prospective applicants<br />

widen their subject knowledge.<br />

Delivering sessions online does come<br />

with challenges – it’s especially hard<br />

to read a room and see how well your presentation is being<br />

received on a Zoom call when most students don’t choose to<br />

share their video! I miss being able to visit our link schools and<br />

chat to students in person. I’m even missing those six-hour train<br />

journeys to the North West and trying to navigate my way round<br />

the Cumbrian countryside to different schools… the trips might<br />

have been tiring but the views (as pictured) were well worth it!’<br />

<strong>The</strong> Revd Katherine Price, Chaplain<br />

‘In my introduction on the<br />

Queen’s website, I used<br />

to say that members of<br />

<strong>College</strong> would see me<br />

around, and were always<br />

welcome to drop in for<br />

a cup of tea. Being a<br />

Chaplain is about being there, often in an informal and serendipitous<br />

way. So working from home has been a bit of an existential<br />

challenge. Tea just doesn’t taste the same over Wi-Fi! But I have<br />

enjoyed learning to produce YouTube videos – not a skill taught<br />

in ministry training! – for our Virtual Chapel Sunday e-vensong.<br />

Services feature music from the Choir’s impressive back catalogue,<br />

glorious photos of the Chapel interior, and even bells recorded by<br />

our bell ringers. So now members of <strong>College</strong> can “go to Chapel”<br />

without getting out of bed. As our first guest preacher of the term<br />

put it, “God is working from home” – your home!’<br />

7

THE QUEEN’S COLLEGE<br />

News in Brief<br />

Read more on our website: www.queens.ox.ac.uk/news<br />

Queen’s in Minecraft<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>College</strong> was rebuilt earlier this year, in virtual form, as part of<br />

the Oxford Minecraft Project.<br />

‘During the lockdown, a few of us thought it would be a great idea<br />

to start a community of Minecraft builders to work on a project<br />

hoping to recreate a large part of central Oxford,’ said graduate<br />

student Tristan Johnston-Wood. ‘Initially, building took quite some<br />

time but with the help of a group of us and more experience, we<br />

are now able to build a college in about three days. We use a<br />

combination of Google Maps 3D view and street view, as well as<br />

people’s own knowledge of Oxford.’<br />

Oriel, Brasenose, Lady Margaret Hall and All Souls have also<br />

all been completed, as well as buildings such as the University<br />

Church, Radcliffe Camera and the Sheldonian <strong>The</strong>atre.<br />

True Planet<br />

<strong>The</strong> University ran a campaign in the autumn to showcase<br />

Oxford’s global research on climate, energy, food, water,<br />

waste and biodiversity. Several Queen’s academics and<br />

graduate students were featured, including April Burt<br />

(DPhil in Environmental Research, 2017), Prof. Jane Langdale<br />

(Professorial Fellow and Professor of Plant Development),<br />

Joseph Poore (DPhil in Environmental Research, 2016) and<br />

Dr Lindsay Turnbull (Fellow in Plant Sciences).<br />

Find out more at www.ox.ac.uk/trueplanet.<br />

Junior Research<br />

Fellow Awarded<br />

Prize for Outstanding<br />

Doctoral Dissertation<br />

Dr Anna Seigal, Extraordinary Junior<br />

Research Fellow in Mathematics,<br />

was awarded the <strong>2020</strong> Society for<br />

Industrial and Applied Mathematics (SIAM) Richard C. DiPrima<br />

Prize. <strong>The</strong> prize recognises an early career researcher in applied<br />

mathematics and is based on their doctoral dissertation. Anna<br />

obtained her PhD from the University of California, Berkeley, and<br />

joined Queen’s in 2019.<br />

Fellows’ Publications<br />

Professor Seth Whidden (Fellow in French) won a Choice Reviews<br />

Outstanding Academic Title Award in December for his<br />

book Arthur Rimbaud (Reaktion Books, 2018).<br />

In recent months several of our other academics have also published on<br />

a wide range of topics:<br />

Choir Receives<br />

Accolade for<br />

Taverner CD<br />

<strong>The</strong> Choir has been awarded a<br />

prestigious Diapason d’or by the<br />

French classical music magazine<br />

Diapason, for its most recent recording<br />

of music by John Taverner.<br />

Russomania: Russian Culture<br />

and the Creation of British<br />

Modernism (Oxford University<br />

Press, <strong>2020</strong>) by Dr Rebecca<br />

Beasley (Fellow in English)<br />

8<br />

Meeting under the Integral<br />

Sign?: <strong>The</strong> Oslo Congress<br />

of Mathematicians on the<br />

Eve of the Second World<br />

War (American Mathematical<br />

Society, <strong>2020</strong>), co-authored by<br />

Dr Christopher Hollings (Clifford<br />

Norton Senior Research Fellow<br />

in the History of Mathematics)<br />

<strong>The</strong> Trials of Thomas Morton:<br />

An Anglican Lawyer, His Puritan<br />

Foes, and the Battle for a New<br />

England (Yale University Press,<br />

2019) by Prof. Peter Mancall<br />

(Harmsworth Visiting Professor<br />

of American History)

Markheim Prize in<br />

French<br />

www.queens.ox.ac.uk<br />

Undergraduate Wins<br />

Biology Award<br />

First-year Biochemistry student<br />

Seren Ford received an award<br />

from the Salters’ Institute for her<br />

performance in A Level Biology.<br />

She was one of five students<br />

recognised for gaining the highest<br />

marks in the Salters-Nuffield<br />

Advanced Biology exam in 2019.<br />

Humanities Light Night –<br />

‘Oxford Research Unwrapped’<br />

<strong>The</strong> Markheim Prize is awarded annually,<br />

based on the results of a French<br />

translation paper taken by our finalists.<br />

Both this year’s winner, Kanak Shah (right),<br />

and runner-up, Georgina Ramsay, are in<br />

their fourth year studying Joint Honours<br />

English and French. In addition to cash<br />

prizes, Kanak and Georgina were each<br />

sent a bottle of champagne, so they could<br />

celebrate by raising a glass over a Zoom<br />

call with the Provost and French tutors.<br />

‘Usually we invite the winner(s) to a drink<br />

on the gallery and dinner on High Table,’<br />

explained Prof. Seth Whidden (Fellow in<br />

French). ‘<strong>The</strong> coronavirus version was a<br />

really nice hour-long Zoom celebration.’<br />

As part of the national Being Human Festival, and Oxford’s Christmas Light Festival,<br />

a huge video projection was mapped onto the Radcliffe Humanities building on<br />

15 November. <strong>The</strong> video projection by Production Studio, entitled ‘SOURCE: CODE’,<br />

was based partly on the research of Professor Richard Bruce Parkinson (Professorial<br />

Fellow in Egyptology). Watch the video at bit.ly/source-code2019.<br />

‘I research Ancient Egyptian poetry and I’m currently writing a commentary on<br />

the classic “Tale of Sinuhe” from 1850 BC. As part of this I’ve worked with actors,<br />

and in particular the actress/author Barbara Ewing, who’s been a regular visitor to<br />

Queen’s for rehearsals and recordings’, explained Richard. ‘Working with texts as<br />

performances can be an inspirational way of breaking down the traditional restraints<br />

of academic practices, and of exploring a poem’s aesthetic and emotional aspects.<br />

We try to get beyond the philology and let people experience the poem as an<br />

intensely felt work of art and not just as a set text.’ A podcast of the reading can be<br />

found at podcasts.ox.ac.uk/life-sinuhe.<br />

Poster Presentation<br />

Prize for Fourth-Year<br />

Biochemist<br />

Alexander Cui (Biochemistry, 2016) won<br />

the Best Poster Presentation award<br />

in February’s Nuffield Department of<br />

Surgical Sciences Research Away Day.<br />

His achievement is all the more impressive<br />

considering he was the only non-PhD/<br />

post-doc entrant.<br />

Photo © Ian Wallman<br />

9

THE QUEEN’S COLLEGE<br />

Dr Bill Frankland’s Final Paper:<br />

‘Fungal Threats: Good and Bad’<br />

We are honoured to be able to remember and pay<br />

tribute to Dr Bill Frankland (Physiological Sciences, 1930<br />

and Honorary Fellow) by publishing his final article, a<br />

fascinating and wide-ranging account of fungi, on our<br />

website. Bill was a truly remarkable man who never really<br />

retired, and completed his final paper with assistance<br />

from Dr Paul Watkins in March <strong>2020</strong>, shortly before his<br />

death at the age of 108. He was Oxford’s oldest alumnus<br />

and an internationally renowned allergist, who had worked<br />

with Nobel Laureate Alexander Fleming. <strong>The</strong> paper can be<br />

read here: bit.ly/bill-frankland<br />

Bill at an event in 2019, in conversation with Peter Richardson (PPE, 1973), whose<br />

father, E.W.M. Richardson (History, 1928) was a contemporary of Bill. ‘It turned out<br />

while we were chatting that Bill remembered him, which was remarkable!’ said Peter.<br />

Photo © Big T Images.<br />

<strong>College</strong> Medical Society holds<br />

Conference on Medical Innovation<br />

On 16 February the Queen’s <strong>College</strong> Medical Society hosted a<br />

gathering of medical students and members of the wider University<br />

to hear from a diverse set of speakers at the forefront of healthcare<br />

innovation in several sectors across the globe. Topics included<br />

advances in molecular drug technology; innovation in the NHS;<br />

healthcare technology, including the use of virtual reality and<br />

potential role of artificial intelligence; and “frugal innovation” where<br />

economic and technological resources are sparse.<br />

<strong>The</strong> day was hugely enjoyable, and each of the speakers brought<br />

much to consider regarding the future of healthcare systems in an<br />

ever advancing but increasingly disparate global arena.<br />

Queen’s <strong>College</strong> Translation Exchange: an Update<br />

from the Director, Dr Charlotte Ryland<br />

Our second year was full of firsts,<br />

beginning with our inaugural residency for<br />

poetry and translation. This was a perfect<br />

Queen’s collaboration, with the John<br />

Rutherford Centre for Galician Studies<br />

and Modern Poetry in Translation. For the<br />

residency that followed we enjoyed our<br />

first external partnership, with London’s<br />

Pushkin House, and our first exhibition<br />

in the <strong>College</strong> Library. British-born<br />

translator Helena Kernan flew over from<br />

California and was joined by Russian poet<br />

Galina Rymbu. Helena’s account for our<br />

blog beautifully captures the “visceral”<br />

experience of working with Galina in<br />

person for the first time.<br />

Almost immediately after the residency,<br />

the idea of doing any kind of meeting<br />

“in person” became a distant memory, and<br />

we faced the challenge of shifting into the<br />

virtual realm a programme that is all about<br />

encounter, exchange and collaboration.<br />

Our International Book Club lived up to<br />

its name, with the books’ translators<br />

joining our virtual meetings from New York<br />

and Iceland, and participants tuning in<br />

from numerous time zones. Meanwhile,<br />

our committed and creative student<br />

ambassadors transformed their in-school<br />

sessions into “virtual workshops”, which<br />

therefore enjoyed a much wider reach.<br />

We look forward to launching our national<br />

translation prize for young languagelearners<br />

in the coming year, ensuring that<br />

young people across the country remain<br />

connected to cultures and literatures<br />

beyond these borders.<br />

www.queens.ox.ac.uk/translationexchange<br />

Chus Pato, Alba Cid and Erín Moure at the final<br />

event of our Galician residency.<br />

10

www.queens.ox.ac.uk<br />

Consent or Why Saying is (not) Doing<br />

Dr Maximilian Kiener, Extraordinary Junior Research Fellow in Philosophy<br />

their entitlement to decide how others may permissibly interact<br />

with their body or property. <strong>The</strong> other face looks at the person<br />

receiving consent: from there, consent shapes responsibility for<br />

wrongdoing and liability to blame. Whether or not a person had<br />

someone else’s consent when performing a certain act, e.g. a<br />

medical procedure or a sexual act, is key to whether that person<br />

acts wrongly and ought to be criticised. I argue that understanding<br />

how the two faces relate to each other not only advances our<br />

understanding of consent but also of autonomy and responsibility<br />

more generally.<br />

Suppose you could complete your weekly to-do list simply by<br />

*saying* that you have done so. Wouldn’t this be marvellous?<br />

Yes, you may say, but it is also impossible. *Saying* is not *doing*.<br />

But wait. <strong>The</strong>re are important moments in our lives when *saying*<br />

is, in fact, *doing.* One example of such a moment concerns<br />

something that you have already done multiple times, maybe even<br />

just before reading this article.<br />

I am talking about consent and how we grant other people the<br />

permission to do what they could not otherwise permissibly do.<br />

Just by *saying* ‘I consent and give you permission to take my<br />

car’ I actually *do* consent and give you permission, thereby<br />

rendering what would otherwise be theft into a permissible act<br />

of borrowing my car. Just by *saying* ‘I permit you to perform<br />

this medical procedure’ I actually *do* permit my physician to<br />

proceed and render what would otherwise be bodily assault into<br />

appropriate medical care. And just by *saying* or communicating<br />

consent I *do* turn what would otherwise be rape into acceptable<br />

sexual intercourse. Heidi Hurd once described this effect of<br />

consent, i.e. transforming an impermissible act into a permissible<br />

one, as ‘moral magic’. *Saying* sometimes really is *doing*.<br />

But why do we have such a power to consent? What are the<br />

conditions of real and valid consent? What mental capacities do<br />

people need to possess in order to consent? What do they need<br />

to know? What does it take to consent voluntarily as opposed<br />

to consenting under coercion or manipulation? How should we<br />

understand consent in the digital age?<br />

In my research, I am focusing on these questions. I argue that<br />

consent is like the Roman god Janus: it has two faces looking in<br />

two different directions. <strong>The</strong> first face looks at the person giving<br />

consent: from here, consent protects a person’s autonomy and<br />

My research is part of the ERC-sponsored project Roots of<br />

Responsibility, which is based at UCL and Oxford, and led by<br />

John Hyman. One of the core aspects of this project, which is also<br />

particularly relevant to my own research, is the legal distinction<br />

between responsibility, understood as an obligation to explain<br />

one’s conduct to others, and liability, understood as being a<br />

legitimate subject of moral criticism or legal redress. Roots of<br />

Responsibility aims to apply this legal distinction to traditional,<br />

often deadlocked, philosophical debates and thereby reframes<br />

various long-standing disputes. Regarding my own research,<br />

I argue that this distinction is also critical for the Janus-faced<br />

nature of consent.<br />

I am privileged to be collaborating with the other members of<br />

the Roots of Responsibility team. In addition, my role as an<br />

Extraordinary Junior Research Fellow at Queen’s and the affiliation<br />

to the Faculty of Philosophy at Oxford have provided a versatile<br />

and fruitful network for exchanging ideas and fostering my<br />

philosophical research.<br />

So, I have now said something about my research, but it is time<br />

for me to return to it and actually do it. Unfortunately, saying is not<br />

always doing.<br />

11

THE QUEEN’S COLLEGE<br />

An Interview with Nicolas Pasternak Slater<br />

Nicolas Pasternak Slater (Russian and<br />

German, 1958), nephew of Boris Pasternak,<br />

is the author of a new translation of Doctor<br />

Zhivago, his uncle’s masterpiece, published by<br />

the Folio Society last year and illustrated with<br />

works by Boris’s father, Leonid Pasternak. He<br />

spoke to us about this very special project, his<br />

time at Queen’s, and the art of translation.<br />

When did you first read Doctor Zhivago,<br />

and what did you make of it then?<br />

I first started reading the novel in 1956, when I<br />

was eighteen. That was a typed carbon copy<br />

that had just been smuggled from Moscow<br />

to Oxford by Isaiah Berlin, a friend of Boris<br />

Pasternak’s and of ours. I had trouble reading<br />

the very faint pages, and didn’t get far because I could only read<br />

it on my limited weekend leaves from National Service. Before<br />

long the two fat volumes disappeared – they were needed by the<br />

translators.<br />

Photo © Philippe Vermes<br />

So I really came to the book three years later, in 1959, when I<br />

was an undergraduate at Queen’s reading Russian and German.<br />

My tutor for modern Russian literature was Max Hayward, then<br />

a fellow at St Anthony’s, whose translation of Doctor Zhivago<br />

(with Manya Harari) had appeared the previous year. Max gave<br />

me several tutorials on the novel, which immensely improved my<br />

understanding of it. But I think I only appreciated it properly the<br />

next time I read it, almost sixty years later, when I translated it for<br />

the Folio Society.<br />

I find it a masterpiece on several levels. It has a sweeping theme<br />

– Russia through the first quarter of the 20th century, when the<br />

country experienced two revolutions, a world war, a civil war and<br />

a famine, and changed its character for ever; but all these events<br />

are seen from a human level, through the lives of brilliantly drawn<br />

individuals, one of whom, Zhivago himself, is very close to the<br />

author. It’s a piece of beautiful writing, with particularly striking and<br />

moving descriptive passages.<br />

You sadly never had the opportunity to meet your uncle.<br />

Can you explain why that was?<br />

included. I was apprehensive enough already<br />

about the treatment I would receive there, as the<br />

nephew of a public pariah; and although I turned<br />

up on the quayside fully expecting to sail with the<br />

rest of the group, it was not a total surprise to be<br />

banned at the last minute.<br />

What did you enjoy most about your time<br />

as an undergraduate and what were your<br />

next steps?<br />

My three years at Queen’s were very happy<br />

ones. Singling out what I enjoyed most is<br />

impossible. I found the work fascinating,<br />

I made many friends and enjoyed the social life,<br />

Queen’s was a beautiful college to live in (I was<br />

particularly fond of my second-year room in<br />

Little Drawda), and I remember the weather as always sunny…<br />

it’s not difficult to be happy in one’s early twenties!<br />

After graduating I spent two years at university in Milan helping<br />

to research automatic translation by computer. I was the<br />

Russian/English specialist in our unit. That was an intellectual<br />

challenge that I felt was just up my street. However, two things<br />

happened in my second year there: the unit ran into problems<br />

with its sponsors, which threatened its survival, and I myself<br />

fell seriously ill with hepatitis. Forcibly confined to hospital in<br />

Milan for six weeks, I became intrigued by my disease and had<br />

many fascinating conversations with my consultant. <strong>The</strong> upshot<br />

was that I decided to return to England and study medicine.<br />

I became a haematologist, looking after patients with conditions<br />

ranging from leukaemia to sickle cell disease, and ended up as a<br />

consultant at St Thomas’ Hospital in London. I retired from that<br />

position in 1998.<br />

With the gradual easing of the Cold War in 1959, the British Council<br />

organised the first Anglo-Soviet student exchange programme. I<br />

got a place on it, to spend a year at Leningrad University studying<br />

Russian literature. However, by that time Doctor Zhivago had already<br />

been published in the West, flouting the Soviet ban on it; and<br />

Pasternak had been awarded the 1958 Nobel Prize for Literature,<br />

which the Soviet government saw as a slap in the face. Not<br />

surprisingly for those years, Boris was in deep disgrace, subjected<br />

to vicious public attack and humiliation; and his entire family was<br />

Lydia and Josephine Pasternak reading. Leonid Pasternak, oil, 1920<br />

12

www.queens.ox.ac.uk<br />

And how did your return to translation work come about?<br />

Languages have always fascinated me, and throughout my life I<br />

have enjoyed acquiring more of them. I made it a principle always<br />

to have a decent working knowledge of the language of any<br />

country I visited, and that amounted to a good many languages<br />

by the end. <strong>The</strong>re could be special challenges about that. When I<br />

married, my wife and I were due to take a cruise from Marseille<br />

to Odessa for our honeymoon. However, once again there<br />

was trouble with our Soviet visas so we had to disembark from<br />

the steamer one stop earlier – in Istanbul. That meant a lot of<br />

intensive study of Turkish on board ship. My new wife was very<br />

understanding.<br />

But my interest in languages has also made me very aware<br />

of prose style in English, and it was a small step from there to<br />

becoming a translator into English when I retired from medicine.<br />

I had done a number of medical translations before that, and<br />

knew that I liked the work. <strong>The</strong> first major literary work that came<br />

my way was a collection of Boris Pasternak’s letters to his family<br />

in England (his parents and both sisters). Our family held those<br />

letters, and they clearly deserved to be translated. That collection<br />

was published by the Hoover Press at Stanford University, and<br />

after that one thing led to another.<br />

How difficult is it to convey the author’s tone<br />

when translating?<br />

I think that capturing the tone of a work is an integral part of doing<br />

the translation; it should come naturally, so far as it can be done<br />

at all. You have to “listen” to the author’s voice in the original, let it<br />

pervade you, and try to stay faithful to it. That sometimes means<br />

sticking close to the way the author has phrased something,<br />

but sometimes it means the opposite – finding a new way of<br />

saying the same thing, while trying to reproduce the cadences,<br />

the linguistic associations, the music of the original – something<br />

that a literal translation often can’t do. Of course it can be very<br />

frustrating, when the target language just won’t do the things that<br />

the source language has done.<br />

and indeed much of the beauty of the language, tended to get lost<br />

in the process. <strong>The</strong> translators were well aware of this at the time.<br />

<strong>The</strong> second translation, published in the USA by Pevear and<br />

Volokhonsky in 2010, takes a different approach. It appears to aim<br />

for maximum fidelity to the vocabulary and sentence structure of<br />

the original – almost a “literal translation”, in fact. <strong>The</strong> drawback<br />

of this approach is that sentences often become strained<br />

and unnatural in English, with peculiar syntax and recondite<br />

vocabulary.<br />

Is there a particular work or author that you’ve most<br />

enjoyed translating?<br />

<strong>The</strong> author I have most enjoyed translating is Pasternak,<br />

including not only Doctor Zhivago but also his letters to his family.<br />

Here he writes in a very different vein, mostly free and easy and<br />

conversational, but sometimes agonisingly emotional, or angry,<br />

or bitterly satirical, or heart-rendingly despondent. Apart from<br />

Pasternak, I have greatly enjoyed translating Tolstoy (<strong>The</strong> Death<br />

of Ivan Ilyich and a number of enchanting short stories). He is a<br />

consummate stylist: every word he chooses is meant to be just<br />

what it is and where it is, and I found myself translating him with<br />

awe and respect.<br />

What skills do you think a good translator needs?<br />

Close familiarity with the source language, the same plus a sense<br />

of style and register in one’s own (target) language, and a lot of<br />

human empathy.<br />

What was the most difficult element of working on<br />

Doctor Zhivago?<br />

<strong>The</strong> most challenging aspect, perhaps, was the knowledge that I<br />

was translating a poet, and that the language of the English had<br />

to be particularly harmonious, rounded, natural, and free from<br />

stumbling-blocks. I don’t claim to have succeeded, but I certainly<br />

tried my best. And I was very conscious that this was a family<br />

work. Not that I felt under extra pressure, rather the opposite<br />

– I felt very close to the author through his two Oxford sisters,<br />

whom I had known and loved for fifty years. I could hear their<br />

voices in his; there were even family expressions I knew. I was<br />

translating a family member and a friend, and it felt different.<br />

<strong>The</strong> translation took me about a year and a half, working fairly<br />

flat out. I was very aware of the other two existing translations,<br />

and kept quite a file of notes on how my solutions differed from<br />

theirs. <strong>The</strong> first English translation, by Hayward and Harari (1958)<br />

was done under enormous time pressure, and the overriding<br />

consideration, as it feels to me, was to produce an English<br />

narrative that ran smoothly. Many nuances of style and meaning,<br />

Pine trees on the Baltic coast. Leonid Pasternak, watercolour<br />

13

THE QUEEN’S COLLEGE<br />

Hydrogen as an Energy Source<br />

Professor Peter Dobson OBE, Emeritus Fellow<br />

<strong>The</strong> awareness of the need to reduce the burning of hydrocarbons<br />

that emit carbon dioxide has now been apparent for over a<br />

decade and the gradual appearance of battery electric vehicles<br />

on our roads is one indication of public acceptance of this need.<br />

Recently there have been demands to reduce the use of natural<br />

gas for domestic heating and cooking, and there are advocates<br />

who want us to use electrical power for replacing this. Heavy<br />

industry such as steel-making and cement consumes large<br />

quantities of coal and gas resulting in carbon dioxide emissions.<br />

All of which begs the question: what, if any, are the alternatives?<br />

Hydrogen is one of the most obvious replacements because when<br />

it burns it only releases water vapour and if it is used in a fuel cell<br />

it creates “clean” electricity and releases water. Hydrogen can be<br />

distributed via pipelines, using existing gas networks with some<br />

modifications, and it can be used in cookers and boilers with<br />

relatively minor modifications. It is a reducing agent, hence it can<br />

be used in steel making and it can provide heat for most heavy<br />

industry applications. Hydrogen can also be compressed and<br />

carried in pressurised tanks in vehicles. So what are the barriers<br />

to its widespread adoption? As in most things, it is mainly in the<br />

“cost”, but there are also some side issues.<br />

Currently 95% of the world’s hydrogen is made by steam<br />

reforming of natural gas and this releases large quantities of<br />

carbon dioxide! <strong>The</strong> problem of capturing, and using or storing,<br />

the emitted carbon dioxide has not yet been solved at the sort<br />

of scale that will be needed. <strong>The</strong> steam reforming produces<br />

hydrogen at a cost of around £1.64 per kg if the CO 2 is released<br />

into the air and estimated to be £1.90 per kg if the CO 2 is<br />

captured and stored. Electrolysis of water using renewable energy<br />

from wind and solar could result in hydrogen at around £4.70 per<br />

kg and there is a lot of effort to drive down this cost by the use of<br />

more efficient and cheaper electrolyser catalysts. Electrolysis to<br />

form hydrogen would be a good way of storing the excess energy<br />

generated by wind and solar generators. <strong>The</strong>re are methods<br />

of generating hydrogen from waste plastics or fossil fuel, being<br />

investigated at Oxford, that could make pure hydrogen and solid<br />

carbon, which could have a high intrinsic value and be stored<br />

easily and safely, but the projected costs are not yet known.<br />

How do these costs compete with fossil fuel? It is difficult to give<br />

direct comparisons because of the differing tax and fuel duty, but<br />

we can take a medium-sized car powered by diesel and compare<br />

it to a similar electric vehicle powered by a fuel cell (FCEV) and<br />

hydrogen. <strong>The</strong> cost per mile of the diesel vehicle is £0.17 per mile<br />

as against £0.25 per mile for the hydrogen FCEV, but currently<br />

there is no high fuel tax on the hydrogen. <strong>The</strong> cost of the fuel cell<br />

electric vehicles themselves is also very high compared to diesel<br />

(currently three times and not likely to reduce by much).<br />

FCEVs offer a much longer range than battery EVs and they can<br />

be refilled in minutes rather than the hours needed for recharging<br />

a battery. <strong>The</strong>re may be widespread public concern about filling<br />

stations that use hydrogen, and coupled with the high cost<br />

of FCEVs this might be a significant barrier to their adoption.<br />

However, there are some obvious candidates for FCEVs in the<br />

form of buses, delivery vans, trucks, farm vehicles and possibly<br />

light railways. All of these could have safe self-contained hydrogen<br />

fuelling depots that pose less risk.<br />

Hydrogen is definitely worth serious consideration as the energy<br />

vector in our attempt to achieve zero carbon emissions. If the<br />

Oxford research by Professor Peter Edwards in the Department<br />

of Chemistry can be economically scaled up, it also solves part of<br />

the plastic waste issue.<br />

Peter Dobson is Emeritus Professor of Engineering Science in<br />

Oxford and he collaborates with Professor Peter Edwards on a<br />

range of energy issues. He is also a visiting professor at UCL<br />

and King’s <strong>College</strong> London where he is engaged in research on<br />

nanotechnology and biosensing.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Coradia iLint hydrogen fuel cell electric train operates in Lower Saxony, Germany. This could<br />

be an efficient clean alternative to many current diesel trains and it does not require the large<br />

infrastructure of overhead cables, and only emits water.<br />

14

www.queens.ox.ac.uk<br />

Hawksmoor Dr awings<br />

Michael Riordan, <strong>College</strong> Archivist<br />

Design for the west side of the front quadrangle <strong>The</strong> west side today – photo © Brian <strong>The</strong>ng (Literae Humaniores, 2015)<br />

In the early eighteenth century the Provost, William Lancaster,<br />

had a great interest in architecture and played a crucial role in the<br />

<strong>College</strong>’s decision to demolish its existing buildings and replace<br />

them with something more fashionably classical. Lancaster<br />

turned to Nicholas Hawksmoor, best known today for his London<br />

churches, but then just beginning to emerge from the shadows of<br />

Wren and Vanbrugh, both of whom he had assisted.<br />

Hawksmoor had to include the recently built Library and the<br />

Williamson Building (in the north-east corner of what is now Back<br />

Quad), but otherwise could let his imagination fly in designing<br />

a whole new college. He produced seven different schemes or<br />

‘propositions’ which he laid out in twenty drawings. <strong>The</strong>se are<br />

kept in the <strong>College</strong> Library and have recently been scanned and<br />

uploaded to the Digital Bodleian site (digital.bodleian.ox.ac.uk)<br />

where they can be viewed for free.<br />

<strong>The</strong> great architectural historian, Sir Howard Colvin, wrote in<br />

his book on Unbuilt Oxford that they were the ‘fiasco’ of an<br />

‘expensive architect with a penchant for adding extravagant and<br />

functionally unnecessary gestures’. This is somewhat harsh:<br />

although none of the drawings were adopted as what was<br />

actually built, features from all of Hawksmoor’s ‘propositions’ were<br />

incorporated into the Queen’s we know today. <strong>The</strong> final plans<br />

were probably agreed by Lancaster and the Master Mason William<br />

Towneshend, drawing on Hawksmoor’s ideas and discussions<br />

with other members of the University interested in architecture<br />

like George Clarke of All Souls and the Dean of Christ Church,<br />

Henry Aldrich.<br />

As well as giving a fascinating idea of what Queen’s might have<br />

looked like, the plans provide important evidence of the process<br />

involved in the rebuilding of the <strong>College</strong>, and an insight into<br />

Hawksmoor himself who a few years later would design the<br />

Clarendon Building and redevelop All Souls.<br />

For more on Hawksmoor and the drawings, see an article by<br />

Dr Eleonora Pistis in the <strong>College</strong>’s Insight magazine: bit.ly/<br />

insight-2012. <strong>The</strong>re is also a short film on the rebuilding of the<br />

<strong>College</strong> at bit.ly/queensarchitecture.<br />

Design for the High Street façade<br />

15

Events Calendar <strong>2020</strong>–21*<br />

Details for all events can be found at www.queens.ox.ac.uk/events<br />

Saturday 12 September <strong>2020</strong> Old Members’ Dinner & AGM Ticketed<br />

Thursday 24 September <strong>2020</strong> Queen’s Women’s Network in London Ticketed<br />

Saturday 26 September <strong>2020</strong> Benefactors’ Dinner (rescheduled from June) Ticketed (by invitation only)<br />

Saturday 17 October <strong>2020</strong> Jubilee Gaudy Lunch (1950, 1960 and 1970) Ticketed (by invitation only)<br />

Saturday 21 November <strong>2020</strong> ‘Ten Years Later’ Lunch (2010) Ticketed (by invitation only)<br />

Saturday 19 December <strong>2020</strong> Boar’s Head Gaudy (1986 and 1987) Ticketed (by invitation only)<br />

Saturday 9 January 2021 Needle & Thread Gaudy (1976 and 1977) Ticketed (by invitation only)<br />

Thursday 15 April 2021 Queen’s <strong>College</strong> Old Members’ Dinner in Washington DC (tentative date) Ticketed<br />

Saturday 17 April 2021 Queen’s <strong>College</strong> Old Members’ Dinner in New York<br />

(part of the 2021 Oxford North America Reunion weekend) Ticketed<br />

Saturday 15 May 2021 Taberdars’ Society Lunch Ticketed (by invitation only)<br />

Saturday 19 June 2021 PPE Centenary Celebrations Ticketed (by invitation only)<br />

Saturday 3 July 2021<br />

Benefactors’ Dinner including an exclusive performance of <strong>The</strong> Changeling,<br />

written by Old Member Thomas Middleton (1598) Ticketed (by invitation only)<br />

Sunday 4 July 2021 Performance of <strong>The</strong> Changeling, written by Old Member Thomas Middleton (1598)<br />

Ticketed<br />

*In the current circumstances, please note that these dates may be subject to change. We will keep you informed and issue ticket<br />

refunds for any event cancelled by Queen’s.<br />

In addition to the above, there are also several other events in the pipeline including a Provost’s Lecture in London, as well as regional<br />

UK and continental Europe events. We will also be looking at how we can make our events more open to online participation and<br />

viewing. For up-to-date information and for booking, please visit www.queens.ox.ac.uk/OMevents.<br />

West Cloister<br />

© Jemma Hayward<br />

Old Members’ Dinner and AGM <strong>2020</strong>: Saturday 12 September, 6:30 for 7:00pm.<br />

Booking now open online at: www.queens.ox.ac.uk/OMD<strong>2020</strong>. RSVP by Friday 28 August.<br />

All Old Members are welcome to attend.<br />

QUEEN’S PHOTOGRAPHY COMPETITION<br />

We are starting a new photo competition this year,<br />

open to all Queen’s students, Old Members, Fellows<br />

and staff. <strong>The</strong>re are two categories – ‘Queen’s Life’<br />

and ‘Oxford’ – with cash prizes for the top three<br />

entries in each. Please enter your photos (old or<br />

new) by 31 August <strong>2020</strong>. See the full rules and how<br />

to enter here:<br />

www.queens.ox.ac.uk/photo-competition COLLEGE RECORD <strong>2020</strong><br />

Your communication preferences<br />

If you wish to update your contact details or communication preferences,<br />

you can do so online at<br />

www.queens.ox.ac.uk/update-my-details;<br />

by email to oldmembers@queens.ox.ac.uk;<br />

or by returning any of the forms enclosed with our hard copy publications.<br />

Call for Venues –<br />

<strong>The</strong> Queen’s Women’s Network<br />

Thanks to all our contributors and to Emily Downing and the Old Members’ Office team<br />

Editor: Claire Hooper<br />

Design & printing: Holywell Press Ltd<br />

Please let us know by emailing oldmembers@queens.<br />

ox.ac.uk if you might be able to provide a large meeting<br />

space (for around 50 to 100 people) as a venue for a<br />

future event, in or around the London area.<br />

You can submit your news for inclusion in the <strong>College</strong><br />

Record by 1 September <strong>2020</strong>, via our website<br />

(www.queens.ox.ac.uk/college-record-<strong>2020</strong>)<br />

or by post to the Old Members’ Office.<br />

Old Members’ Office, <strong>The</strong> Queen’s <strong>College</strong>, High Street, Oxford, OX1 4AW<br />

www.queens.ox.ac.uk<br />

Email: oldmembers@queens.ox.ac.uk | Telephone: 01865 279217 Registered Charity 1142553<br />

@queenscollegeoxford @queenscollegeoxford @Queens<strong>College</strong>Ox www.youtube.com/queenscollegeox