DOWNLOAD the Educator's Guide here - Mendel Art Gallery

DOWNLOAD the Educator's Guide here - Mendel Art Gallery

DOWNLOAD the Educator's Guide here - Mendel Art Gallery

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

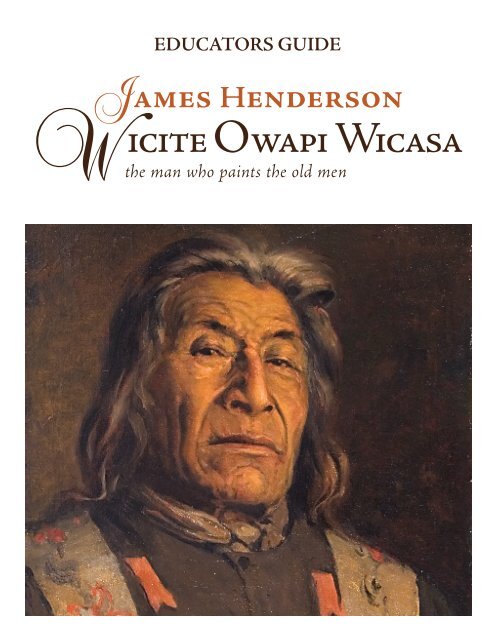

EDUCATORS GUIDE

Copyright ©2009 by <strong>the</strong> <strong>Mendel</strong> <strong>Art</strong> <strong>Gallery</strong>.<br />

The <strong>Mendel</strong> <strong>Art</strong> <strong>Gallery</strong> acknowledges <strong>the</strong> collective knowledge of present and past public programming staff in developing this educator’s guide, including Laura<br />

Kinzel, Carol Wylie, Megan Bocking, Kelly Van Damme, Adrian Stimson, Alexandra Badzak, Noreen Neu, Cheryl Meszaros, Neal McLeod, Ray Keighley, and Elizabeth<br />

Ma<strong>the</strong>son. We also credit <strong>the</strong> co-curators of <strong>the</strong> James Henderson exhibition, Dan Ring and Neal McLeod, along with catalogue essay contributors Linda Many Guns,<br />

James Lanigan, and Brigid Ward. Special thanks to communications staff at <strong>the</strong> <strong>Mendel</strong>, particularly Ed Pas and Lindsey Rewuski, for editing and design.<br />

This educators’ guide, exhibition, and o<strong>the</strong>r related programming was made possible through a contribution from <strong>the</strong> Museums<br />

Assistance Program, Department of Canadian Heritage. PotashCorp is <strong>the</strong> title sponsor of James Henderson: Wicite Owapi Wicasa: <strong>the</strong><br />

man who paints <strong>the</strong> old men. The <strong>Mendel</strong>’s annual School Hands-on Tour Program is also sponsored by PotashCorp.<br />

OPEN DAILY<br />

9AM–9PM<br />

FREE ADMISSION<br />

950 SPADINA CRESCENT E.<br />

BOX 569, SASKATOON, SK<br />

CANADA, S7K 3L6<br />

Public Programs: 306-975-8052<br />

(306) 975-7610<br />

MENDEL@MENDEL.CA<br />

WWW.MENDEL.CA

Introduction<br />

The <strong>Mendel</strong> <strong>Art</strong> <strong>Gallery</strong> is pleased to<br />

provide you with this education package<br />

that is designed to supplement your<br />

tour of James Henderson: Wicite Owapi<br />

Wicasa: <strong>the</strong> man who paints <strong>the</strong> old men.<br />

Please visit www.mendel.ca/<br />

henderson for supplemental<br />

material. Portions of <strong>the</strong> upcoming<br />

exhibition catalogue are on this site,<br />

along with printable reproductions,<br />

historical and contemporary context,<br />

interviews, and more. The site can easily<br />

be projected onto a classroom SMART<br />

Board as a teaching aide.<br />

(Cover Image and Above) Sun Walk - Blackfoot,<br />

c. 1924, oil on canvas. Collection of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Mendel</strong><br />

<strong>Art</strong> <strong>Gallery</strong>. Purchased with <strong>the</strong> assistance<br />

of funds from Price Waterhouse, Chartered<br />

Accountants, 1986.

About your Tour<br />

• We recommend that you preview <strong>the</strong> exhibition to best prepare your students.<br />

• The Program <strong>Guide</strong>, assigned to work with your group, will call you a week prior to your visit<br />

to discuss details. We strive to tailor <strong>the</strong> content to meet <strong>the</strong> needs of individual groups and<br />

welcome your ideas.<br />

• Age appropriately, touring groups will explore:<br />

• <strong>the</strong> significance of Henderson as an historical figure in Saskatchewan<br />

• how artists choose <strong>the</strong>ir subject matter<br />

• how an image can evoke multiple memories and associations that vary with each viewer<br />

• landscape and portraiture as art forms<br />

• <strong>the</strong> importance of land to identity<br />

• <strong>the</strong> role that artists play in reflecting individual and community identities<br />

• <strong>the</strong> interaction of settlers with Indigenous peoples<br />

• <strong>the</strong> importance of oral histories to understanding our world<br />

We look forward to learning about art with your group.<br />

Thank you for supporting us in supporting art!<br />

Laura Kinzel<br />

Public Programs Coordinator

How to Use this <strong>Guide</strong>:<br />

• The activities fit into multiple curricula: social studies, language arts, history, media studies, visual<br />

art, and native studies. Flip to <strong>the</strong> section that fits your curriculum needs.<br />

• Each activity is ready-to-use. Do as many as you like, whatever you have time for.<br />

• Each activity is relevant to tour content and can be adapted for most age groups.<br />

• This guide serves as a general introduction to related <strong>the</strong>mes, from learning <strong>the</strong> basics of making<br />

landscapes and portraits to exploring issues around Henderson’s practice. Subjects will be covered<br />

in greater depth during <strong>the</strong> tour.<br />

<strong>Mendel</strong> programs encourage participants to see <strong>the</strong> world in new ways. Our<br />

exhibitions are rated OM—Open Minds Required. We help participants to think<br />

critically about <strong>the</strong> often-confusing world around <strong>the</strong>m, and deliberately challenge<br />

preconceived ideas about art. As a contemporary art gallery, <strong>the</strong> <strong>Mendel</strong> offers<br />

a context for art production that is difficult to replicate in a school environment,<br />

<strong>the</strong>refore providing learners with a unique experience.

Table of Contents<br />

5 About <strong>the</strong> Exhibition<br />

6 Background Information About<br />

James Henderson<br />

8 Curators and Researchers as<br />

Professional <strong>Art</strong> Detectives<br />

Collecting Discussion Activity<br />

Land<br />

10 Introduction to Landscape <strong>Art</strong><br />

The Proverbial Landscape Activity<br />

Categories of Landscape Activity<br />

Looking at <strong>the</strong> Landscape Activity<br />

11 Plein Air Landscape Painting<br />

The Space Between Objects Activity<br />

13 Panoramas<br />

Collective Panorama Activity<br />

14 Identity and Land<br />

Memories of <strong>the</strong> Land Activity<br />

Land Speaks Activity<br />

16 Boosterism<br />

Selling <strong>the</strong> Idea of Place Activity<br />

Boosterism and Colonialism Activity<br />

People<br />

17 Introduction to Portraiture<br />

Portrait Hunt Activity<br />

Verbal/ Dramatic/ Visual Portrait Activity<br />

Symbols Activity<br />

How to Draw a Face Activity<br />

20 Types and Stereotypes<br />

Exploring “Types” Activity<br />

22 Portraits and Photographs<br />

Enlarging Photographs Activity<br />

“Collage You” Activity<br />

Symbols of You Activity<br />

Identity Box Activity<br />

23 Self-Portraits Versus Those<br />

Made by Someone Else<br />

Making Me Activity<br />

24 Who or What Do We Really<br />

See In An Image?<br />

Mirror Portrait Activity<br />

25 Honouring and Monuments<br />

Illuminated Manuscripts Activity<br />

Oral Traditions Activity<br />

Monuments of Memory Activity<br />

27 Related Topics and Resources<br />

for Fur<strong>the</strong>r Research

By connecting Henderson’s portraits of First Nations people and his landscape paintings of<br />

<strong>the</strong> Qu’Appelle Valley and elsew<strong>here</strong> to <strong>the</strong> enduring memories of those who remain and to <strong>the</strong><br />

landscape of our times, we attempt to retrieve memory and connect past and present.<br />

—Dan Ring, Chief Curator, <strong>Mendel</strong> <strong>Art</strong> <strong>Gallery</strong><br />

About <strong>the</strong> Exhibition<br />

This is a major exhibition of <strong>the</strong> portraits,<br />

landscape paintings, and commercial<br />

work of Scottish-born artist James<br />

Henderson (1871 to 1951).<br />

• Henderson was Saskatchewan’s first<br />

professional artist to make a living solely<br />

through his artwork. He is also one of<br />

<strong>the</strong> first nationally and internationally<br />

famous artists in Saskatchewan.<br />

• The exhibition presents Henderson’s<br />

work from <strong>the</strong> Qu’Appelle Valley w<strong>here</strong><br />

he lived, and from Scotland, British<br />

Columbia, Ontario, and Alberta.<br />

• It introduces oral histories of Cree, Blackfoot,<br />

and Dakota peoples based on Henderson’s<br />

portraits of Indigenous peoples.<br />

• Documents including family photos,<br />

samples of his commissioned illuminated<br />

manuscripts, correspondence, and published<br />

articles about his career round out <strong>the</strong> larger<br />

picture of Henderson’s life and passions.<br />

• Photographic source material for<br />

Henderson’s subjects along with a<br />

large photo reproduction of his original<br />

studio reveal his working methods.<br />

• Current video footage of <strong>the</strong> locations<br />

for his landscapes in <strong>the</strong> Qu’Appelle<br />

Valley is juxtaposed with <strong>the</strong><br />

paintings of <strong>the</strong> same locations.<br />

• The exhibition, which fills three of four<br />

main galleries at <strong>the</strong> <strong>Mendel</strong>, includes<br />

a wide variety of two and threedimensional<br />

objects to explore, and will<br />

surely intrigue viewers of all ages.<br />

• With this exhibition <strong>the</strong> <strong>Mendel</strong> has launched<br />

a number of interactive features including<br />

podcasts, and rich web content to gain indepth<br />

access to interviews with key people and<br />

comments on individual artworks on view in <strong>the</strong><br />

gallery space. An interactive SMART Board<br />

will be used as a teaching aide during tours.<br />

The exhibition is co-curated by <strong>Mendel</strong> Chief<br />

Curator Dan Ring and Dr. Neal McLeod,<br />

Associate Professor of Indigenous Studies<br />

at Trent University. The exhibition catalogue<br />

contains essays by several scholars and curators.<br />

An extensive web site for <strong>the</strong><br />

exhibition can be found at<br />

www.mendel.ca/henderson.<br />

James Henderson, Evening, c. 1930<br />

oil on canvas. Collection of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Mendel</strong> <strong>Art</strong> <strong>Gallery</strong>.

Background Information About James Henderson<br />

Below are selected highlights of Henderson’s<br />

life (see <strong>the</strong> web site for more details):<br />

Biography<br />

• James Henderson was born into a middle<br />

class family in Glasgow, Scotland in 1871.<br />

• The son of a sea captain, he took<br />

an apprenticeship in lithographic<br />

printing at age 16.<br />

• He enrolled in night courses at <strong>the</strong><br />

Glasgow School of <strong>Art</strong>, w<strong>here</strong> he was<br />

influenced by <strong>the</strong> Scottish Impressionist<br />

School. Visiting galleries and sketching<br />

from nature nurtured his creative drive.<br />

• In 1900 he married Jean Lang in Glasgow.<br />

• Following employment in London as an<br />

engraver and lithographer, Henderson and<br />

his wife emigrated to Regina in 1910, w<strong>here</strong><br />

he engaged in commercial art assignments.<br />

• Periodic visits to <strong>the</strong> picturesque Qu’Appelle<br />

Valley appealed to Henderson’s artistic<br />

sensibilities, and he relocated with his wife<br />

to Fort Qu’Appelle in 1915 or 1916. The<br />

environment, rich with lakes, dramatic hills,<br />

and meandering coulees probably reminded<br />

<strong>the</strong>m of <strong>the</strong>ir Scottish homeland. They lived<br />

in a house on <strong>the</strong> Qu’Appelle River, 45 miles<br />

east of Regina, for <strong>the</strong> remainder of <strong>the</strong>ir lives.<br />

• Henderson painted his beloved valley in<br />

every season and mood, and lived a quiet<br />

life. Acquaintances described him as a gentle<br />

man with a keen sense of humour, who loved<br />

dogs, music, golf, and visiting friends.<br />

• Henderson died in Regina in 1951, just short of<br />

his 80th birthday. He was buried alongside his<br />

wife, overlooking <strong>the</strong> valley at Fort Qu’Appelle.<br />

About Henderson’s Life<br />

• In addition to painting landscapes, Henderson<br />

also painted portraits. While <strong>the</strong>se include<br />

portraits of Saskatchewan political and<br />

business figures, he more importantly<br />

established a career as a painter of portraits<br />

of Indigenous peoples. T<strong>here</strong> is evidence<br />

that Henderson had a personal relationship<br />

with <strong>the</strong> Indigenous people he painted;<br />

it is thought that a Chief of <strong>the</strong> Standing<br />

Buffalo Reserve near Fort Qu’Appelle named<br />

Henderson as Honorary Chief Wicite Owapi<br />

Wicasa: <strong>the</strong> man who paints <strong>the</strong> old men.<br />

(Researchers have questions about <strong>the</strong> origin<br />

and translation of Henderson’s honorary<br />

Dakota name. The web site and exhibition<br />

catalogue explore this subject in greater detail.)<br />

• Recognizing Henderson’s significant<br />

achievements, <strong>the</strong> University of Saskatchewan<br />

bestowed on him an honorary Doctor of<br />

Laws degree at its spring convocation in<br />

1951. Gordon Snelgrove, Head of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Art</strong><br />

Department, referred to Henderson as <strong>the</strong><br />

“dean of Saskatchewan artists…esteemed<br />

throughout Canada as a painter of first rank.”

Exhibitions and <strong>Art</strong> Career<br />

Henderson’s exhibition history is<br />

lengthy. Below are some highlights.<br />

• His portraits first came to national and<br />

international attention when his work<br />

was included in <strong>the</strong> 1924 and 1925<br />

Canadian arts sections of <strong>the</strong> British<br />

Empire Exhibition in London, England.<br />

• During <strong>the</strong> late 1920s and early 1930s he<br />

exhibited portraits and landscapes in <strong>the</strong><br />

Annual Exhibition of Canadian <strong>Art</strong> at <strong>the</strong><br />

National <strong>Gallery</strong> of Canada in Ottawa, alongside<br />

members of <strong>the</strong> Group of Seven and Emily Carr.<br />

• The National <strong>Gallery</strong> of Canada purchased<br />

one portrait and two landscapes<br />

by him, during this period.<br />

• In 1925 <strong>the</strong> University of Saskatchewan<br />

commissioned Henderson to paint twelve<br />

portraits of Indigenous peoples.<br />

• In <strong>the</strong> 1920s and 1930s he regularly<br />

exhibited in Montreal, Toronto, Regina,<br />

and London, England.<br />

• Henderson travelled in Western Canada,<br />

painting portraits of Indigenous peoples and<br />

exhibiting his works in <strong>the</strong> principal cities.<br />

• In addition to portraits and Qu’Appelle<br />

Valley landscapes, his oeuvre contains<br />

landscapes of British Columbia, Alberta,<br />

Ontario, and Scotland.<br />

• Henderson sold most of his work directly<br />

from his studio in Fort Qu’Appelle.<br />

James Henderson when he first came to <strong>the</strong> Fort,<br />

c. 1915–16. Photographer unknown. Courtesy of<br />

Diane Morris.

Curators and Researchers as<br />

Professional <strong>Art</strong> Detectives<br />

This is <strong>the</strong> first exploration of this magnitude<br />

into <strong>the</strong> life and work of James Henderson. The<br />

exhibition curators wanted to bring toge<strong>the</strong>r<br />

as much of his vast body of work in one<br />

location as possible. In addition to celebrating<br />

Henderson’s prolific career, curators also sought<br />

to examine <strong>the</strong> attitudes of <strong>the</strong> time and <strong>the</strong><br />

impact of his legacy today. This process required<br />

much research over several years from myriad<br />

sources. The result of all this research is an<br />

expansive, inclusive, and remarkable exhibition.<br />

• Substantial new information was discovered,<br />

both fascinating and at times contradictory.<br />

(Touring groups will explore this more fully.)<br />

• T<strong>here</strong> are some exhibition and<br />

archival records, and many anecdotal<br />

remembrances about <strong>the</strong> man.<br />

• No personal journals, diaries, or letters<br />

were found that could give an impression<br />

of his thoughts and ambitions.<br />

• A few quotes from newspaper articles written<br />

about him during or after his life offer some<br />

glimpse into his opinions on art and society.<br />

• Owners of Henderson’s paintings were<br />

sought out. Some readily contributed<br />

works for <strong>the</strong> project, and o<strong>the</strong>rs had to be<br />

convinced about <strong>the</strong> merits of parting with<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir treasures for loan to <strong>the</strong> exhibition.<br />

• T<strong>here</strong> are many more works known<br />

to be in existence that could not<br />

be included in <strong>the</strong> show.<br />

• Curators travelled to places that<br />

Henderson lived and worked, including<br />

Scotland, to piece toge<strong>the</strong>r his life.<br />

• Family photos were revealed<br />

after much word-of-mouth.<br />

• Longtime residents in <strong>the</strong> Qu’Appelle<br />

Valley helped to situate <strong>the</strong> actual locations<br />

that Henderson painted in <strong>the</strong> valley<br />

and provide a history of <strong>the</strong> area.<br />

• Interviews with surviving family members and<br />

acquaintances of <strong>the</strong> subjects in Henderson’s<br />

portraits of Indigenous peoples clarify <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

names and provide a valuable oral history.<br />

• Connections to significant historical figures<br />

abound, including portraits of Chief Sitting<br />

Bull who battled at <strong>the</strong> Little Big Horn River,<br />

Chief Crowfoot who was <strong>the</strong> head chief<br />

of <strong>the</strong> Blackfoot Confederacy and had a<br />

prominent role in Treaty 7 negotiations,<br />

and Honorable Hugh Richardson who<br />

presided over <strong>the</strong> trial of Louis Riel.

Collecting Discussion Activity<br />

The Henderson exhibition was drawn from<br />

private and public collections of artwork,<br />

including <strong>the</strong> <strong>Mendel</strong>’s own Permanent<br />

Collection. Introduce <strong>the</strong> notion of collecting<br />

by asking students <strong>the</strong> following:<br />

• Why do some people like to collect things?<br />

(For example: we like what we collect,<br />

collecting is challenging, we can show off<br />

our efforts, it’s prestigious, collecting things<br />

no one else has is fun, we earn money by<br />

reselling it, it’s an investment, we can increase<br />

our knowledge about a topic, we enjoy<br />

talking to o<strong>the</strong>rs who share our interests).<br />

• Do you collect? What?<br />

• W<strong>here</strong> do you keep it?<br />

• How do you decide what goes<br />

into your collection?<br />

• Who sees it?<br />

Consider asking students to bring in<br />

elements from <strong>the</strong>ir collections for<br />

“show and tell.”<br />

Collection of animals. Photo by Laura Kinzel.

Land<br />

Introduction to Landscape <strong>Art</strong><br />

The landscape is all around us. It is something<br />

that we take for granted and consequently, rarely<br />

take <strong>the</strong> time to appreciate. In o<strong>the</strong>r words,<br />

familiarity can produce apathy. The activities<br />

below introduce students to landscape art.<br />

The Proverbial Landscape Activity<br />

Begin by asking students what landscape<br />

art is (works of art that show features<br />

of <strong>the</strong> natural environment).<br />

• Why would an artist use <strong>the</strong> landscape as<br />

subject matter? (to capture awe and wonder,<br />

it’s ever-changing, artists can experiment<br />

with materials, it’s a fun environment<br />

to work in, artists can scientifically/<br />

geographically/biologically study a place,<br />

<strong>the</strong>y can express a spiritual connection,<br />

artists can learn perspective, etc.)<br />

• Ask students to begin <strong>the</strong> landscape unit by<br />

painting a landscape, to record <strong>the</strong>ir idea<br />

of a landscape painting. Do not give <strong>the</strong>m<br />

any motivational cues. Keep this painting<br />

as a record to compare to a painting <strong>the</strong>y<br />

will produce in <strong>the</strong> classroom after <strong>the</strong><br />

gallery visit. This first work will likely be a<br />

cliché landscape that can be questioned<br />

throughout <strong>the</strong> learning process.<br />

10<br />

Categories of Landscape Activity<br />

Collect reproductions, pictures, photographs,<br />

poems, stories, etc., about <strong>the</strong> landscape.<br />

• Brainstorm with <strong>the</strong> students about how<br />

many different kinds of landscape <strong>the</strong>y see<br />

(barren, rocky, forests, stormy, morning,<br />

seascape, mountains, moody, etc.).<br />

• Develop some categories of landscape<br />

paintings (prairie, with buildings, with people,<br />

close-up, panorama, with animals, etc.).<br />

• What is <strong>the</strong> difference between real<br />

life landscape and pictures? (no<br />

smells, sounds, one point of view)<br />

Looking at <strong>the</strong> Landscape Activity<br />

Outside in nature or looking at reproductions:<br />

• Ask students to look for directions in<br />

<strong>the</strong> environment by noticing horizontal,<br />

vertical and diagonal lines.<br />

• Challenge students to “stretch” <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

eyes. “Find something outside you<br />

haven’t noticed before and draw it.”<br />

• Ask <strong>the</strong>m to investigate textures in<br />

a landscape by taking rubbings of<br />

leaves, bark, and o<strong>the</strong>r surfaces.

Plein Air Landscape Painting<br />

T<strong>here</strong> is ample evidence that James Henderson<br />

painted many of his landscapes on site outdoors.<br />

Plein air is a French phrase meaning “open<br />

air.” Plein air painting, or painting out of doors,<br />

was not common until <strong>the</strong> mid-19th century,<br />

after transportation improved and lightweight<br />

portable equipment was invented (including<br />

tubes for oil paint). These changes facilitated <strong>the</strong><br />

growing desire by artists to paint directly from<br />

nature. Plein air was popularised by <strong>the</strong> French<br />

Impressionists, especially Monet, whose work<br />

captured <strong>the</strong> ever-changing effects of natural<br />

light through active brushstrokes and vibrant<br />

colour. Because <strong>the</strong>y could spontaneously<br />

respond directly to subtle mood and atmospheric<br />

changes, plein air artists were able to develop<br />

new techniques such as rapid brush-work.<br />

Unpredictable wea<strong>the</strong>r, rapidly changing light,<br />

paint that dries too quickly or slowly, even insects<br />

are some of <strong>the</strong> challenges that plein air artists<br />

face—but even <strong>the</strong>se are just part of <strong>the</strong> fun!<br />

Henderson preferred an “impressionist” style<br />

when painting his landscapes—whe<strong>the</strong>r<br />

<strong>the</strong>y depicted <strong>the</strong> Qu’Appelle Valley w<strong>here</strong><br />

he lived most of his life, reflected Scotland<br />

w<strong>here</strong> he was born, or recorded his travels<br />

through British Columbia, Alberta, or Ontario.<br />

His landscapes give a general impression<br />

of <strong>the</strong> scene and captures a mood, through<br />

active brush strokes, blended colours,<br />

and scant attention to fine details.<br />

11<br />

James Henderson, Road to <strong>the</strong> Lake, 1935, oil on canvas.<br />

Collection of James Lanigan.

The Space Between Objects Activity<br />

In this activity students will go outdoors to work<br />

en plein air using any colourful drawing or painting<br />

material. They can use a viewfinder (explained<br />

below) to isolate a section of <strong>the</strong> landscape. If<br />

<strong>the</strong> wea<strong>the</strong>r is poor, this activity can be done<br />

from photographs that feature large foreground<br />

trees that frame <strong>the</strong> scene (try a Google image<br />

search [trees, landscape] or old calendars).<br />

• Begin by referring to <strong>the</strong> Henderson painting<br />

Road to <strong>the</strong> Lake (see page 11) or o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

reproductions. See how <strong>the</strong> large trees frame<br />

<strong>the</strong> landscape. The close-up, detailed trees<br />

in <strong>the</strong> foreground create contrast with <strong>the</strong><br />

smaller and more distant elements in <strong>the</strong><br />

landscape. The illusion of depth has been<br />

created by having large detailed elements in<br />

<strong>the</strong> foreground, and shapes that gradually<br />

get smaller as <strong>the</strong>y recede into space.<br />

• Introduce <strong>the</strong> idea that one way to incorporate<br />

trees into a scene is to start with <strong>the</strong><br />

background and add <strong>the</strong> trees on top of<br />

it. But a more interesting way is to start by<br />

making <strong>the</strong> big trees in <strong>the</strong> foreground, <strong>the</strong>n<br />

filling in <strong>the</strong> background elements between<br />

<strong>the</strong> trees. That way, <strong>the</strong> space between <strong>the</strong><br />

objects (negative space) is as interesting as<br />

<strong>the</strong> objects <strong>the</strong>mselves. Explain that this is <strong>the</strong><br />

approach you would like <strong>the</strong> students to take.<br />

• To draw <strong>the</strong> scene, students first sketch <strong>the</strong><br />

main parts in pencil, <strong>the</strong>n add colour with<br />

pastels or paint. Pay attention to <strong>the</strong> space<br />

between <strong>the</strong> leaves, branches, and trees<br />

(negative space). Also notice <strong>the</strong> subtle<br />

visual changes in <strong>the</strong> sky. If <strong>the</strong> drawing<br />

includes water, be sure to reflect <strong>the</strong> clouds<br />

12<br />

on its surface. Carefully look at <strong>the</strong> lights<br />

and darks in <strong>the</strong> scene and choose/blend<br />

<strong>the</strong> colours and materials accordingly.<br />

Generally, light colours advance and dark<br />

colours recede. Highlights and shadows<br />

can add depth. Are those shadows really<br />

black, or can you see o<strong>the</strong>r colours, too?<br />

Tip to using viewfinders<br />

Sometimes <strong>the</strong> thought of drawing or painting<br />

an entire landscape can seem overwhelming.<br />

If students hold a viewfinder up and peer<br />

through it, <strong>the</strong>y can isolate <strong>the</strong> more interesting<br />

parts of <strong>the</strong> landscape. Empty slide mounts<br />

or hand-cut windows in stiff paper can both<br />

function as viewfinders. Practice holding<br />

it at different distances from <strong>the</strong> face.<br />

Using a viewfinder to isolate sections of <strong>the</strong> landscape.

Panoramas<br />

A panorama is a two-dimensional work<br />

of art that depicts a viewpoint of 180<br />

degrees or more. In some of his paintings<br />

Henderson depicted vast views of <strong>the</strong><br />

landscape. While we can debate whe<strong>the</strong>r<br />

some of Henderson’s paintings technically<br />

are panoramas, we can certainly agree that<br />

many reflected broad stretches of land.<br />

13<br />

Collaborative Panorama Activity<br />

Have students sit outdoors or in <strong>the</strong> classroom<br />

in a semi circle.<br />

• Using viewfinders (see The Space Between<br />

Objects Activity on page 12) and <strong>the</strong> devices<br />

of perspective to draw <strong>the</strong> landscape, ask<br />

each student to depict <strong>the</strong> small portion of<br />

<strong>the</strong> panoramic space <strong>the</strong>y see through <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

viewfinder. You could mark out <strong>the</strong> range of<br />

space for each student to view.<br />

• Pin all <strong>the</strong> drawings toge<strong>the</strong>r on a long wall to<br />

re-create <strong>the</strong> larger panoramic view. It’s okay<br />

if some images overlap and shift perspective.

Identity and Land<br />

W<strong>here</strong> we are born, w<strong>here</strong> we grow up, and<br />

w<strong>here</strong> we move to—whe<strong>the</strong>r by choice or<br />

circumstance—all influence who we become.<br />

In his essay for <strong>the</strong> exhibition catalogue, Neal<br />

McLeod discusses how a lifestyle of hunting,<br />

trapping, fishing, ga<strong>the</strong>ring plants, and <strong>the</strong><br />

changing rhythms of <strong>the</strong> seasons sustained <strong>the</strong><br />

livelihood of Indigenous peoples; land, humans,<br />

and animals were deeply intertwined. When a<br />

dam built in <strong>the</strong> Qu’Appelle Valley resulted in<br />

flooding, <strong>the</strong> landscape was forever altered,<br />

and by extension so too were <strong>the</strong> peoples of<br />

<strong>the</strong> region. For more information, McLeod’s<br />

interviews with elders and knowledge keepers<br />

from <strong>the</strong> valley can be accessed at www.<br />

mendel.ca/henderson, read in <strong>the</strong> exhibition<br />

catalogue, or previewed in <strong>the</strong> exhibition.<br />

14<br />

James Henderson, The Marsh, 1918, oil on canvas.<br />

Collection of James Lanigan.<br />

The Marsh, by James Henderson, depicts <strong>the</strong><br />

marsh at <strong>the</strong> end of Pasqua Lake before <strong>the</strong><br />

building of <strong>the</strong> dam in Fort Qu’Appelle in 1943<br />

caused extensive flooding. Prior to this flooding<br />

<strong>the</strong> marsh was a traditional Indigenous hunting<br />

area and was also used by settlers for <strong>the</strong> same<br />

purpose. This is a contested issue today and<br />

negotiations are still under way to compensate<br />

members of <strong>the</strong> Pasqua reserve for <strong>the</strong> flooding.

Memories of <strong>the</strong> Land Activity<br />

Ask students to collect stories surrounding<br />

family origins from family members.<br />

• W<strong>here</strong> have <strong>the</strong>ir ancestors lived,<br />

how did <strong>the</strong> land influence <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

lifestyles, and what has changed?<br />

• Share <strong>the</strong>se stories in class and discuss <strong>the</strong><br />

different relationships <strong>the</strong> students’ ancestors<br />

may have expressed about <strong>the</strong> land.<br />

• Ask students to draw one of <strong>the</strong><br />

stories that helped <strong>the</strong>m to understand<br />

<strong>the</strong> world in a new way.<br />

Check out <strong>the</strong> Homelands section<br />

of <strong>the</strong> ARTSask web site for related<br />

responses by o<strong>the</strong>r artists, www.artsask.<br />

ca, or http://artsask.uregina.ca/en/<br />

collections/<strong>the</strong>mes/homelands.<br />

1<br />

Land Speaks Activity<br />

Obtain a copy of <strong>the</strong> short children’s book,<br />

Qu’Appelle (see below) by David Bouchard<br />

(paintings by Michael Lonechild). It recounts a<br />

famous love story about a young brave who must<br />

leave his betro<strong>the</strong>d to lead a war party against<br />

<strong>the</strong> Blackfoot. Broken hearted, his betro<strong>the</strong>d<br />

dies. Cree elders say you can still hear <strong>the</strong> brave<br />

searching for his girlfriend. Mohawk poet Pauline<br />

Johnson tells ano<strong>the</strong>r version of <strong>the</strong> story that<br />

educators could also investigate with students.<br />

• After reading <strong>the</strong> book, ask students to interview<br />

a place. This place could be a personification<br />

of <strong>the</strong>ir school, a favorite hiding place, <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

backyard, bedroom, closet, grandparents’<br />

kitchen, etc. Generate a list of questions with<br />

<strong>the</strong> class for <strong>the</strong>m to use during <strong>the</strong>ir interviews.

Boosterism<br />

James Henderson, Winnipeg, under <strong>the</strong> proposed scheme, will become one of <strong>the</strong> most superb capitols of<br />

Canada, c. 1913, newspaper clipping. Courtesy of Diane Morris, Fort Qu’Appelle, Saskatchewan.<br />

In <strong>the</strong> early twentieth century <strong>the</strong> prairie was<br />

promoted as a great place in which to live and<br />

invest. Images that promoted <strong>the</strong> benefits of<br />

Canadian settlement were widely distributed to<br />

European audiences. These images were often<br />

exaggerated and excessively optimistic. James<br />

Henderson played a role in Boosterism through<br />

his commercial work, as demonstrated by his<br />

imagined plan for <strong>the</strong> city of Winnipeg and o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

commissions. The topic of prairie Boosterism<br />

and Henderson’s role are discussed more<br />

extensively in Dan Ring’s catalogue essay.<br />

1<br />

Selling <strong>the</strong> Idea of Place Activity<br />

Ask students to think about how <strong>the</strong>y can “sell”<br />

<strong>the</strong> idea that <strong>the</strong>ir school is <strong>the</strong> best in <strong>the</strong> city<br />

to attend. They will make a poster to entice<br />

future students. Exaggerate, celebrate, brag,<br />

and ignore <strong>the</strong> negatives.<br />

Boosterism and Colonialism Activity<br />

Older students can investigate <strong>the</strong> larger role<br />

that Boosterism played in colonialism and <strong>the</strong><br />

displacement of Indigenous peoples.

People<br />

Introduction to Portraiture<br />

The portraits painted by James Henderson<br />

were ei<strong>the</strong>r commissioned by o<strong>the</strong>rs, or were<br />

done because he was interested in <strong>the</strong> subject<br />

and could earn a living by selling his work.<br />

Portrait Hunt Activity<br />

Begin by asking students “What is a portrait?”<br />

Traditionally a portrait is defined as a<br />

representation of a person, especially of <strong>the</strong> face,<br />

but <strong>the</strong>re are grey areas in <strong>the</strong> definition. Clearly<br />

when someone represents himself or herself,<br />

developed from life, it is a portrait. Some people<br />

argue that a representation of a person long dead<br />

is not a true portrait as it is done from imagination<br />

and <strong>the</strong> evidence of accuracy is sketchy. What<br />

about when an actor portrays someone else in<br />

a movie? Is a representation of any living thing a<br />

portrait, such as a painting of a dog or a tree?<br />

• Students will collect portraits from many<br />

sources and of diverse people. Display<br />

<strong>the</strong> images and make a list of what<br />

information can be gleaned from portraits<br />

(age of <strong>the</strong> sitter, social status, nationality,<br />

state of mind, occupation, tastes).<br />

1<br />

• What are <strong>the</strong> functions of a portrait?<br />

A portrait can function as:<br />

• a historical document (hairstyles,<br />

clo<strong>the</strong>s fashion, a record of what a<br />

historical person looked like, etc.),<br />

• a symbol (<strong>the</strong> Queen’s photo in<br />

many classrooms, a Christ figure),<br />

• a statement about “<strong>the</strong> state of<br />

things” (Van Gogh’s self portrait),<br />

• a study in composition<br />

(Picasso’s portraits),<br />

• a means of self-exploration<br />

(Rembrandt’s self-portraits),<br />

• a representation of familial<br />

bonds (Mary Cassatt’s paintings<br />

of mo<strong>the</strong>rs with children)<br />

• a record of social status (painting<br />

by James Henderson of a judge,<br />

on view in <strong>the</strong> Saskatchewan<br />

Legislative Building in Regina)<br />

• and more.<br />

• Using <strong>the</strong> collected images, cut and paste<br />

portraits with conflicting information,<br />

such as <strong>the</strong> hands of a model, head of a<br />

businessman, and clo<strong>the</strong>s of a rock star.

Verbal/Dramatic/Visual Portrait Activity<br />

Ask students to select a real person that <strong>the</strong>y are<br />

familiar with, and have <strong>the</strong>m write a description of<br />

that person’s physical features and personality.<br />

• Ask students to act out a portrait of that person.<br />

• Then instruct students to draw or paint a<br />

portrait of that person. They should include<br />

objects in <strong>the</strong>ir picture that tell more about <strong>the</strong><br />

person, and keep in mind colour symbolism and<br />

distinguishing features.<br />

1<br />

Symbols Activity<br />

A symbol is something which is itself and yet<br />

stands for something else or evokes a meaning<br />

beyond itself. A portrait can be a symbol in itself,<br />

and it can use symbols to convey information<br />

about <strong>the</strong> sitter. Referring to portraits of important<br />

people, ask students what kind of character is<br />

implied in each portrait.<br />

• Discuss <strong>the</strong> role that gesture, stance, and<br />

expression plays in informing <strong>the</strong> viewer.<br />

• How might students act out concepts such<br />

as authority, genius, spirituality, stupidity or<br />

wealth?<br />

• What symbols are frequently used in our<br />

culture?<br />

• Have students draw symbolic self-portraits of<br />

what <strong>the</strong>y want to be 20 years from now, using<br />

props and symbols to identify <strong>the</strong> profession.

How to Draw a Face Activity<br />

This basic activity teaches <strong>the</strong> proportions of a<br />

face. Reinforce that <strong>the</strong>se are guidelines, that<br />

every face is a little bit different. Ask students to:<br />

• Draw an egg shape for <strong>the</strong> head.<br />

• Draw a light line half way down across <strong>the</strong> face<br />

to mark <strong>the</strong> eyes; eyes are half way between top<br />

of head and chin (or lower on young children).<br />

• Divide this line into five sections to show w<strong>here</strong><br />

eyes go; eyes are in <strong>the</strong> second and fourth<br />

sections. Eyes are like skinny, lopsided lemons,<br />

tilted up at <strong>the</strong> outside corners. T<strong>here</strong> is an eye<br />

length across <strong>the</strong> nose.<br />

• The bottom of <strong>the</strong> nose is half way between<br />

eyes and chin. The nose is like a flat, curvy “M”<br />

with “C’s” on ei<strong>the</strong>r side.<br />

• A line half way between <strong>the</strong> nose and chin<br />

marks <strong>the</strong> bottom of <strong>the</strong> mouth; <strong>the</strong> mouth<br />

is closer to <strong>the</strong> nose than <strong>the</strong> chin. The line<br />

between <strong>the</strong> lips is a bit like a flattened “M.”<br />

• Now consider shading. Observe w<strong>here</strong> shadows<br />

are around <strong>the</strong> nose, cheeks, eyes, etc.<br />

• Add hair. Look for <strong>the</strong> basic shape and <strong>the</strong>n<br />

work on highlights and shadows, adding a few<br />

strands for emphasis.<br />

• Shoulders are a head’s width on each side.<br />

1

Types and Stereotypes<br />

James Henderson lived and painted during a time<br />

when <strong>the</strong> dominant culture was often blatantly<br />

racist. Like many settlers of his age, Henderson<br />

seemed to believe that “<strong>the</strong> Indian” was a<br />

vanishing race, and <strong>the</strong>refore he romanticized<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir past in his depictions of <strong>the</strong>m.<br />

“<strong>Art</strong>ists who came to North America<br />

from Europe were <strong>the</strong> first to make<br />

visual images of aboriginal people for<br />

Europeans who knew little of <strong>the</strong> new<br />

world and its people. Many of <strong>the</strong> artists<br />

<strong>the</strong>mselves knew little of <strong>the</strong> new world<br />

and its people. The images <strong>the</strong>y created<br />

of aboriginal people did not accurately<br />

reflect how <strong>the</strong>se people saw <strong>the</strong>mselves.<br />

These pictures depicted how Europeans<br />

saw <strong>the</strong>m. Many of <strong>the</strong>se images were<br />

romantic notions of aboriginal people<br />

which really did not exist.” (Claiming<br />

Ourselves: iyiniwak anohc, educators<br />

guide, Neal McLeod and Elizabeth<br />

Ma<strong>the</strong>son, <strong>Mendel</strong> <strong>Art</strong> <strong>Gallery</strong>, 1996)<br />

While James Henderson spent time getting to<br />

know <strong>the</strong> local band members, and apparently<br />

was given an honourary Dakota name, curators<br />

today feel that several of his portraits contain<br />

confusing information about <strong>the</strong> subjects, such<br />

as Dakota headdresses on Blackfoot people,<br />

people in portraits who o<strong>the</strong>rs today say do not<br />

look like <strong>the</strong> person depicted, etc. (Tour groups<br />

will explore this more fully during <strong>the</strong>ir visits.) As<br />

we find errors or inconsistencies around some<br />

of Henderson’s portraits of Indigenous peoples,<br />

what are we, <strong>the</strong>n, to think about every portrait<br />

that he painted?<br />

20<br />

Linda Many Guns has written an essay in <strong>the</strong><br />

catalogue about peoples from <strong>the</strong> Blackfoot<br />

Nation/Blackfoot Confederacy who are depicted<br />

in Henderson’s portraits. Excerpts are on <strong>the</strong><br />

exhibition web site and within <strong>the</strong> exhibition itself.<br />

James Henderson, The Philosopher, A Sioux Indian, no<br />

date, oil on canvas. Collection of <strong>the</strong> MacKenzie <strong>Art</strong><br />

<strong>Gallery</strong>, University of Regina Collection. Gift of Mr. Norman<br />

MacKenzie.

Exploring “Types” Activity<br />

James Henderson painted many portraits.<br />

Sometimes he identified <strong>the</strong> name of <strong>the</strong><br />

sitter in <strong>the</strong> title, and o<strong>the</strong>r times he (or o<strong>the</strong>rs)<br />

titled his paintings “Sioux Indian” or “Female<br />

Indian Head.” This can imply a kind of generic<br />

handling of those sitters. This is especially<br />

troublesome given <strong>the</strong> colonial enterprise that<br />

worked to assimilate Indigenous people into<br />

settler culture, and <strong>the</strong> treatment of Indigenous<br />

people as a vanishing race. Ask students how<br />

<strong>the</strong>y would feel if someone painted a likeness<br />

of <strong>the</strong>m and <strong>the</strong>n titled it “Student Head.”<br />

Would <strong>the</strong> image still be of <strong>the</strong>m, and what<br />

o<strong>the</strong>r messages might it give to viewers?<br />

The above conversation leads to a<br />

discussion of “types” and stereotypes.<br />

• Ask students to ga<strong>the</strong>r pictures of a<br />

wide variety of character types.<br />

• Then ask <strong>the</strong>m to establish categories of<br />

“types”; some may be ambiguous and o<strong>the</strong>rs<br />

may be more subjective. Cartoon characters<br />

and caricatures can be part of this conversation.<br />

• Ask students to choose a “type” of person and<br />

draw it according to accepted conventions<br />

(saint with halo, villain in black, grandma with<br />

glasses, nerd with unfashionable clothing).<br />

• Display <strong>the</strong>se works and ask students<br />

to guess what “type” is represented<br />

and explain <strong>the</strong>ir reasoning.<br />

21<br />

• Now discuss <strong>the</strong> usefulness of this kind<br />

of “typing” and <strong>the</strong> in<strong>here</strong>nt assumptions.<br />

In what ways is “typing” helpful, and<br />

in what ways is it damaging?<br />

• Pictures do not show exactly <strong>the</strong> whole<br />

truth; ask students if <strong>the</strong>y have seen things<br />

on television that aren’t completely true.<br />

What about a game, movie or toy that<br />

isn’t as exciting as <strong>the</strong> commercial?<br />

• Move this discussion forward by allowing<br />

students to talk about <strong>the</strong>ir diverse ethnic<br />

backgrounds. How do <strong>the</strong>y feel stereotyped?<br />

What effect does this have on <strong>the</strong>m?

Portraits and Photographs<br />

To paint his portraits, James Henderson often<br />

enlarged photographs using a grid system.<br />

Enlarging Photographs Activity<br />

Teach students how to enlarge a portrait.<br />

• Draw a grid of 1.27 cm squares<br />

(½ inch) on top of a photo.<br />

• Then draw a grid of 2.54 cm squares<br />

(1-inch) on ano<strong>the</strong>r piece of paper.<br />

• Now copy what you see in each square<br />

of <strong>the</strong> photo onto <strong>the</strong> big paper.<br />

“Collage You” Activity<br />

In this activity students will collage toge<strong>the</strong>r<br />

photographs of various aspects of <strong>the</strong>mselves<br />

to present a unique self-portrait. Images<br />

can include close-ups of body parts, long<br />

shots, and photos of props that tell more<br />

about <strong>the</strong> student. Black and white prints<br />

from digital photos would work fine.<br />

• Students will collage <strong>the</strong>ir fragments<br />

into a long horizontal format to create<br />

a landscape-like narrative.<br />

• Consider how ordering and layout<br />

changes <strong>the</strong> message.<br />

22<br />

Symbols of You Activity<br />

In this activity students will draw symbols<br />

of <strong>the</strong>mselves on an enlarged portrait.<br />

• A school photograph can be enlarged using a<br />

computer or a photocopier. Enlarging provides<br />

more surface to draw upon. Ask students to<br />

enhance <strong>the</strong> enlarged image with symbols<br />

of <strong>the</strong>mselves to explore <strong>the</strong>ir inner selves.<br />

Identity Box Activity<br />

The most meaningful and successful<br />

artworks come when <strong>the</strong> artist has direct<br />

experience with <strong>the</strong> subject or <strong>the</strong>me. This<br />

activity explores <strong>the</strong> use of visual symbols<br />

to tell personal histories and stories.<br />

• Students will first discuss and list various<br />

groups to which <strong>the</strong>y belong (family,<br />

sports, religious, musical, school, age,<br />

ethnicity, jobs, fan clubs, hobbies, etc).<br />

• Students will <strong>the</strong>n expand <strong>the</strong>ir list to include<br />

more abstract ideas that relate to <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

identity (people <strong>the</strong>y admire or dislike, current<br />

events, issues, favourite places to go).<br />

• Next <strong>the</strong>y will collect symbols from any source,<br />

and may alter <strong>the</strong>m to change <strong>the</strong>ir meaning.<br />

These symbols can be put into individual<br />

boxes and when examined will be able to<br />

communicate about <strong>the</strong> maker’s identity.<br />

• What ideas and symbols are common to<br />

<strong>the</strong> class as a whole? Would people outside<br />

<strong>the</strong> class understand <strong>the</strong>se symbols?<br />

How have different symbols been used to<br />

explain <strong>the</strong> same ideas? Did some symbols<br />

stand for multiple ideas even when <strong>the</strong><br />

student only intended one meaning?

Self-Portraits versus Those Made by Someone Else<br />

Some people are concerned that Henderson<br />

was a non-Indigenous person painting portraits<br />

of Indigenous people. They question how much<br />

he truly knew about his subjects and his intent<br />

behind making <strong>the</strong> portraits. While his homeland<br />

of Scotland experienced a colonial past similar<br />

to Indigenous peoples in Canada, this may<br />

or may not have made him sympa<strong>the</strong>tic.<br />

Making Me Activity<br />

Consider <strong>the</strong> differences between an image<br />

you make of yourself and an image that<br />

someone else has made of you. Would both<br />

reflect <strong>the</strong> same thoughts and impressions?<br />

• Ask students to really think about how<br />

<strong>the</strong>y would like to present <strong>the</strong>mselves<br />

in a portrait, and what location and<br />

props <strong>the</strong>y would like to use.<br />

• Then have <strong>the</strong>m draw a self-portrait or take<br />

a photo of <strong>the</strong>mselves using a timer.<br />

• Next, ask students to make<br />

images of each ano<strong>the</strong>r.<br />

• Lastly, compare <strong>the</strong> end results.<br />

23

Who or What Do We Really See in An Image?<br />

In his catalogue essay, Neal McLeod references<br />

an old Cree story about people who “mistakenly<br />

identify o<strong>the</strong>rs as <strong>the</strong>mselves.” He explains<br />

that people in <strong>the</strong> story are unaware that<br />

<strong>the</strong>y are actually looking into a mirror while<br />

<strong>the</strong>y make assumptions. James Henderson’s<br />

paintings act as mirrors through which we<br />

can learn a great deal about Indigenous<br />

peoples, <strong>the</strong> landscape, Henderson himself,<br />

and our own attitudes. T<strong>here</strong> is always a<br />

context for how an image is interpreted.<br />

24<br />

Mirror Portrait Activity<br />

In this activity, students will draw, paint, and<br />

collage an image of <strong>the</strong>mselves as a hand mirror<br />

reflects back <strong>the</strong>ir representation of <strong>the</strong>mselves.<br />

• First, ask students to draw a picture of<br />

<strong>the</strong>mselves from behind, showing <strong>the</strong>mselves<br />

holding up a hand-held mirror.<br />

• Then, in this mirror <strong>the</strong>y will depict a reflection<br />

of <strong>the</strong>mselves. This reflection could be a<br />

photograph that is cut out and glued onto<br />

<strong>the</strong> mirror, or it could be a more abstract<br />

representation filled with symbols, colours, and<br />

portions of <strong>the</strong>ir face.<br />

• Viewers of <strong>the</strong> completed work will see both <strong>the</strong><br />

back of <strong>the</strong>ir head plus <strong>the</strong> image in <strong>the</strong> mirror.

Honouring and Monuments<br />

James Henderson received many commissions<br />

to illustrate and hand-letter certificates, memorial<br />

rolls of honour, and testimonial documents to<br />

acknowledge dignitaries and important events.<br />

Certificate awarded to nurse. Attributed to James Henderson,<br />

vintage gelatin silver print on paper of an original illuminated<br />

address. Photo by Don Hall. Collection of <strong>the</strong> MacKenzie <strong>Art</strong><br />

<strong>Gallery</strong>.<br />

2<br />

Illuminated Manuscripts Activity<br />

Show students examples from <strong>the</strong> Henderson<br />

web site (in <strong>the</strong> “Early Life” section), or show<br />

<strong>the</strong>m examples of illuminated manuscripts from<br />

any source.<br />

• Ask students to select a person or event <strong>the</strong>y<br />

wish to honour and <strong>the</strong>n write a brief passage to<br />

acknowledge that person.<br />

• Using calligraphy or fancy hand lettering <strong>the</strong>y<br />

will design a page, carefully write <strong>the</strong> message,<br />

and draw small vignettes that relate to <strong>the</strong><br />

person being honoured.

Oral Traditions Activity<br />

Much of <strong>the</strong> research for <strong>the</strong> James Henderson<br />

exhibition involved speaking to people<br />

who knew Henderson personally, live in <strong>the</strong><br />

Qu’Appelle Valley, know <strong>the</strong> sitters depicted in<br />

his portraits, or have o<strong>the</strong>r personal knowledge<br />

of content related to Henderson’s practice.<br />

Honouring <strong>the</strong> oral traditions and stories<br />

by knowledge keepers is a very important<br />

component of <strong>the</strong> Henderson project.<br />

• In preparing for tours, classrooms<br />

can bring in Indigenous storytellers to<br />

share <strong>the</strong>ir culture and teachings.<br />

• Students can also interview <strong>the</strong>ir own family<br />

members or visit a seniors’ residence to<br />

engage in <strong>the</strong> stories from o<strong>the</strong>r generations.<br />

• Discuss with students what <strong>the</strong>y<br />

learn through this process.<br />

2<br />

Monuments of Memory Activity<br />

In his catalogue essay, Neal McLeod talks<br />

about how James Henderson’s paintings<br />

serve as monuments. He says <strong>the</strong> images<br />

evoke ano<strong>the</strong>r telling or memory for someone<br />

else. Henderson’s paintings honour, remind,<br />

challenge, teach, and contradict.<br />

• Ask students to select any Henderson<br />

portrait or landscape painting, and write or<br />

talk about what it makes <strong>the</strong>m think about.<br />

Address to <strong>the</strong> Prince of Wales from <strong>the</strong> Government<br />

of Saskatchewan, Oct. 4, 1919. Attributed to James<br />

Henderson, vintage gelatin silver print on paper of an<br />

original illuminated address by James Henderson.<br />

Collection of <strong>the</strong> MacKenzie <strong>Art</strong> <strong>Gallery</strong>.

Related Topics and Resources for Fur<strong>the</strong>r Research<br />

• Web site dedicated to James Henderson: Wicite Owapi<br />

Wicasa: <strong>the</strong> man who paints <strong>the</strong> old men:<br />

www.mendel.ca/henderson<br />

• For diverse information on <strong>the</strong> Qu’Appelle Valley, a 2006<br />

<strong>Mendel</strong> <strong>Art</strong> <strong>Gallery</strong> exhibition project through Virtual<br />

Museums of Canada: Qu’Appelle—Past/Present/Future:<br />

http://www.mendel.ca/quappelle<br />

• For an extensive educator resource for Saskatchewan<br />

and Canadian art with lesson plans, developed by <strong>the</strong><br />

Ministry of Education and University of Regina around <strong>the</strong><br />

collections of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Mendel</strong> <strong>Art</strong> <strong>Gallery</strong> and MacKenzie <strong>Art</strong><br />

<strong>Gallery</strong> in Regina. The <strong>the</strong>mes of Homelands, Isolation and<br />

Landscape, Identity, and Place all contain exciting artists<br />

and activities: www.artsask.ca.<br />

• See <strong>the</strong> Saskatchewan Western Development Museum’s<br />

<strong>Guide</strong> for Teachers: Saskatchewan 1905 to 2005. A<br />

free copy was sent by <strong>the</strong>m in 2008 to every school in<br />

Saskatchewan. It contains numerous lesson plans around<br />

multiple aspects of settlement.<br />

• The exhibition contains portraits and references to<br />

several important people and events. Research any of <strong>the</strong><br />

following:<br />

• Standing Buffalo<br />

• Big Bear<br />

• Chief Crowfoot<br />

• Sitting Bull<br />

• 1885 Resistance<br />

• Trial of Louis Riel (portrait of Justice Hugh Richardson<br />

who presided over <strong>the</strong> trial and sentenced Riel)<br />

• The Blackfoot Confederacy<br />

• Dakota (Sioux) peoples in Saskatchewan<br />

• Cree peoples in Saskatchewan<br />

• Treaty Numbers 4, 6, 7<br />

• 1870 when <strong>the</strong> Hudson’s Bay company sold Rupert’s<br />

Land to <strong>the</strong> Dominion of Canada<br />

• <strong>the</strong> Group of Seven artists in Canada<br />

2<br />

• To explore more about o<strong>the</strong>r non-Indigenous artists and<br />

photographers who recorded early Indigenous peoples, see<br />

<strong>the</strong> work of Edward Curtis, Paul Kane, and Edmund Morris.<br />

• For o<strong>the</strong>r educators guides developed by <strong>the</strong> <strong>Mendel</strong> <strong>Art</strong><br />

<strong>Gallery</strong> that could be used for follow-up after <strong>the</strong> tour:<br />

http://www.mendel.ca/schools/resource/index.html<br />

• DiverCity: Immigrant Youth Stories in Saskatoon<br />

• SlammED: raw poetic explorations into moral<br />

intelligence for grades 5 though 8<br />

• Office of <strong>the</strong> Treaty Commissioner: www.otc.ca<br />

• Indian and Nor<strong>the</strong>rn Affairs Canada: www.ainc-inac.gc.ca<br />

• For more lesson plans around Indigenous peoples:<br />

www.edselect.com/first_nations_people.htm<br />

• Canadian Museum of Civilization for web modules<br />

for Kindergarten to Grade 12 under Civilization Clicks,<br />

http://www.civilisations.ca/cmc/exhibitions/onlineexhibitions/first-peoples<br />

(First Peoples of Canada or<br />

Gateway to Aboriginal Heritage)<br />

• For a children’s book related to First Nations stories about<br />

<strong>the</strong> Qu’Appelle Valley, see Qu’Appelle by David Bouchard,<br />

paintings by Michael Lonechild<br />

• Through <strong>the</strong> Eyes of <strong>the</strong> Cree: The <strong>Art</strong> of Allen Sapp:<br />

http://www.virtualmuseum.ca/Exhibitions/allensapp/

OPEN DAILY<br />

9AM–9PM<br />

FREE ADMISSION<br />

950 SPADINA CRESCENT E.<br />

BOX 569, SASKATOON, SK<br />

CANADA, S7K 3L6<br />

Public Programs: 306-975-8052<br />

(306) 975-7610<br />

MENDEL@MENDEL.CA<br />

WWW.MENDEL.CA