BPLS Reform Program Guide - National Computer Center

BPLS Reform Program Guide - National Computer Center

BPLS Reform Program Guide - National Computer Center

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

<strong>BPLS</strong> REFORM PROGRAM<br />

GUIDE<br />

Promoting Local Business Permit and Licensing<br />

System <strong>Reform</strong> in the Philippines<br />

December 2011<br />

This publication was produced by Nathan Associates Inc. for review by the United States Agency for<br />

International Development.

<strong>BPLS</strong> REFORM PROGRAM<br />

GUIDE<br />

Promoting Local Business Permit and Licensing<br />

System <strong>Reform</strong> in the Philippines<br />

DISCLAIMER<br />

This document is made possible by the support of the American people through the United States Agency for<br />

International Development (USAID). Its contents are the sole responsibility of the author or authors and do<br />

not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States government.

Contents<br />

Acronyms v<br />

Acknowledgements vii<br />

1. Global Competitiveness and <strong>BPLS</strong> Streamlining 1<br />

1.1 Competitiveness Defined 1<br />

1.2 Global Surveys on Competitiveness 1<br />

1.3 <strong>National</strong> Surveys on Competitiveness 3<br />

1.4 Awards and Incentives 6<br />

2. Understanding <strong>BPLS</strong> <strong>Reform</strong>s 9<br />

2.1 What is <strong>BPLS</strong> streamlining? 9<br />

2.2 Legal Basis for <strong>BPLS</strong> <strong>Reform</strong>s 10<br />

2.3 The Government <strong>BPLS</strong> <strong>Program</strong> 11<br />

2.4 Institutional Structures and Mechanisms 17<br />

3. Past <strong>BPLS</strong> <strong>Reform</strong>s in the Philippines 21<br />

3.1 <strong>BPLS</strong> Initiatives Between 2001–2010 21<br />

3.2 <strong>BPLS</strong> Initiatives Since 2010 26<br />

3.3 Lessons Learned 29<br />

4. Accelerating <strong>BPLS</strong> <strong>Reform</strong>s 33<br />

4.1 Challenges 33<br />

4.2 Next Steps 35<br />

References 39<br />

Appendix A. <strong>BPLS</strong> Unified Form<br />

Appendix B. Assessing Business Processes<br />

Appendix C. Milestones in the <strong>BPLS</strong> <strong>Reform</strong>s <strong>Program</strong>

IV<br />

Illustrations<br />

Figures<br />

Figure 2-1. Macro-View of <strong>BPLS</strong> Processes 9<br />

Figure 2-2. <strong>BPLS</strong> Streamlining <strong>Program</strong> Coverage by LGU Level 16<br />

Figure 2-3. Institutional Support for <strong>BPLS</strong> <strong>Reform</strong>s 18<br />

Tables<br />

Table 1-1. Philippine Ranking in Global Competitiveness Surveys, 2006-2012 2<br />

Table 1-2. Global Competitiveness Rankings of ASEAN Nations, 2011 2<br />

Table 1-3. Ease of Doing Business for Select ASEAN Countries, 2010-2011 3<br />

Table 1-4. Comparison of Philippine Cities in Processing Business Start-Ups 4<br />

Table 1-5. Top Three Ranked Cities in the PCCRP, 2009 6<br />

Table 2-1. Regional Allocation of Cities and Municipalities in the <strong>BPLS</strong> <strong>Program</strong> 16<br />

Table 3-1. <strong>BPLS</strong> Implementation in Central Luzon 22<br />

Table 3-2. <strong>BPLS</strong> Pilot Areas in the Visayas 24<br />

Table 3-3. Status of <strong>BPLS</strong> Streamlining in Targeted LGUs by Region, July 2011 27<br />

Table 3-4. Summary of <strong>BPLS</strong> Accomplishments in Butuan and Cagayan de Oro 28<br />

Table 3-5. Summary of Official Development Assistance to <strong>BPLS</strong> <strong>Reform</strong>s 30

Acronyms<br />

AECID Agencia Española de Cooperación Internacional para el Desarrollo (Spanish<br />

Agency for International Development Cooperation)<br />

APC Asian Institute of Management Policy <strong>Center</strong><br />

ARTA Anti-Red Tape Act<br />

ASEAN Association of Southeast Asian Nations<br />

BFP Bureau of Fire Protection<br />

<strong>BPLS</strong> Business Permitting and Licensing System<br />

BOSS Business One-Stop Shop<br />

BPLO Business Permitting and Licensing Office<br />

CDA Cooperative Development Authority<br />

CESO Career Executive Service Board<br />

CLIPC Central Luzon Investment Promotion <strong>Center</strong><br />

CLICC Central Luzon Investment Coordinating Council<br />

CLGCFI Central Luzon Growth Corridor Foundation Inc.<br />

CICT Commission on Information and Communication Technology<br />

CSC Civil Service Commission<br />

CSOs Civil Society Organizations<br />

DBS Doing Business Survey<br />

DILG Department of the Interior and Local Government<br />

DLG Working Group on Decentralization and Local Government<br />

DP Decentralization Project<br />

DTI Department of Trade and Industry<br />

e<strong>BPLS</strong> Electronic Business Permitting and Licensing System<br />

eGov4MD Electronic Governance for Municipal Development<br />

FSIC Fire Safety Inspection Certificate<br />

GCI Global Competitiveness Index<br />

GCY Global Competitiveness Yearbook<br />

GIC Working Group on Growth and Investment Climate<br />

GIZ Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (German Technical<br />

Cooperation Agency)<br />

IEC Information, Education and Communication<br />

IFC International Finance Corporation<br />

ISO International Organization for Standardization<br />

IMD International Institute if Management Development<br />

JMC 2009 Joint Memorandum Circular No. 01 Series of 2009<br />

JMC 2010 Joint Memorandum Circular No. 01 Series of 2010

VI<br />

JDAO Joint Department Administrative Order<br />

LCE Local Chief Executive<br />

LCP League of Cities of the Philippines<br />

LGA Local Government Academy<br />

LGU Local Government Unit<br />

LINC-EG Local Implementation of <strong>National</strong> Competitiveness for Economic Growth<br />

LIR Local Investment <strong>Reform</strong><br />

LMP League of Municipalities of the Philippines<br />

LRED Local Regional Economic Development<br />

MAP Management Association of the Philippines<br />

MDC Mayor’s Development <strong>Center</strong><br />

MOA Memorandum of Agreement<br />

MOC Memorandum of Commitment<br />

NCR <strong>National</strong> Capital Region<br />

NEDA <strong>National</strong> Economic Development Authority<br />

NERBAC <strong>National</strong> Economic Research and Business <strong>Center</strong><br />

NGA <strong>National</strong> Government Agencies<br />

NCC1 <strong>National</strong> Competitiveness Council<br />

NCC2 <strong>National</strong> <strong>Computer</strong> <strong>Center</strong><br />

MCC Millennium Challenge Corporation<br />

PCCI Philippine Chamber of Commerce and Industry<br />

PCCRP Philippine Competitiveness Ranking Project<br />

PDF Philippine Development Forum<br />

PhilHealth Philippine Health Insurance Corporation.<br />

PBR Philippine Business Registry<br />

PSP Private Sector Promotion<br />

RSP Regulatory Simplification Project<br />

SEC Securities and Exchange Commission<br />

SBRP Simplified Business Registration Process<br />

SNDB Sub-<strong>National</strong> Doing Business<br />

SSS Social Security System<br />

TAG Transparency Accountable Governance<br />

TOT Training of Trainers<br />

TWG Technical Working Groups<br />

USAID United States Agency for International Development<br />

WEF World Economic Forum

Acknowledgements<br />

Managed for USAID/Philippines by Nathan Associates Inc., LINC-EG—Local Implementation<br />

of <strong>National</strong> Competitiveness for Economic Growth—is a three-year project that began in 2008.<br />

LINC-EG assists policymakers in improving the environment for private enterprise to establish,<br />

grow, create jobs, and help reduce poverty.<br />

This guide was developed under the LINC-EG Project to assist the Philippine government in<br />

improving subnational systems for business permitting and licensing (<strong>BPLS</strong>). It is intended as a<br />

reference document for national and local governments and builds on the work of the Philippine<br />

government and other development partners, noting some past achievements. More significantly,<br />

the guide explains recent policy developments that provide for the cross-departmental, legal and<br />

institutional basis for <strong>BPLS</strong> reform and how these can help to support and fast track further<br />

improvements in the interface between government and business.<br />

Consultant Lucy Lazo conducted extensive research and writing, Ofie Templo provided<br />

administrative oversight of the information gathering stage, Alid Camara and Mikela Trigilio of<br />

Nathan Associates provided additional analysis and editing of the report. Executive Director<br />

Marivel Sacendoncillo and the staff of the Local Government Academy, an arm of the<br />

Department of the Interior and Local Government, were particularly supportive with their time<br />

and advice on what to include in this document.

1. Global Competitiveness and<br />

<strong>BPLS</strong> Streamlining<br />

1.1 COMPETITIVENESS DEFINED<br />

Competitiveness encompasses the institutions, policies, and other factors that determine a<br />

country’s level of productivity (World Economic Forum 2010). The level of productivity, in turn,<br />

determines the level of prosperity that a country can sustain. Thus, competitive countries tend to<br />

produce higher incomes for their citizens. Productivity also determines an economy’s rate of<br />

return on investments. Because investments—physical, human, and technological—are<br />

fundamental drivers of economic growth, a competitive economy is one that is likely to grow<br />

faster in the medium to long term.<br />

Institutions have a strong bearing on competitiveness and growth because they influence<br />

investment decisions and the organization of production. 1 Of relevance in this report is the<br />

institutional aspect of operations efficiency as manifested in excessive bureaucracy and red tape<br />

involved in the granting of business permits.<br />

1.2 GLOBAL SURVEYS ON COMPETITIVENESS<br />

Since 2008 the Philippines has been falling in the ranks of annual competitiveness surveys, a fact<br />

that has given impetus to efforts to streamline business permitting and licensing systems in the<br />

country. The three main surveys that measure competitiveness across countries are<br />

• The Global Competitiveness Index (GCI) published by the World Economic Forum<br />

(WEF),<br />

• The Doing Business Survey (DBS) of the World Bank (WB) and the International<br />

Finance Corporation (IFC), and<br />

• The Global Competitiveness Yearbook (GCY) of the International Institute of<br />

Management Development (IMD).<br />

Published annually since 2005, the GCI has about 111 indicators covering 12 categories of the<br />

microeconomic and macroeconomic foundations of national competitiveness. The DBS analyzes<br />

regulations that apply to domestic small and medium-size companies using sets of 11 indicators.<br />

1 Institutions are one of the 12 pillars of competitiveness in the Global Competitiveness Report 2010-2011<br />

(World Economic Forum 2010).

2 <strong>BPLS</strong> R EFORM P ROGRAM G UIDE<br />

In 2011 the DBS covered 183 economies. The GCY has 331 criteria in 5 economic areas and<br />

covered 59 countries in 2011.<br />

The Philippines has always ranked in the bottom third of countries covered in these surveys<br />

(Table 1-1). From 2008 to 2011, the country's rank deteriorated across the board, although the<br />

GCI for 2011-2012 reported a 10 point improvement for the Philippines. According to the GCI<br />

the Philippines is weakest in indicators for corruption, bureaucracy, infrastructure efficiency, and<br />

policy stability. The GCY cites weakness in international investment, infrastructure, and<br />

education; and DBS calls for improvement in starting a business, dealing with construction<br />

permits, and protecting investors.<br />

Table 1-1<br />

Philippine Ranking in Global Competitiveness Surveys, 2006-2012<br />

Survey 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012<br />

GCI 71<br />

(125)<br />

75<br />

(122)<br />

71<br />

(131)<br />

GCY 42 45 40 43 39 41 -<br />

DBS 121<br />

(175)<br />

126<br />

(175)<br />

133<br />

(178)<br />

71<br />

(134)<br />

141<br />

(181)<br />

SOURCES: Compiled from the Global Competitiveness Reports, 2006-2011, IIMD and DB surveys.<br />

In gauging its competitiveness, the Philippines must benchmark itself against developing<br />

economies and its Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) neighbors who are all vying<br />

for foreign investment. Unfortunately, the Philippines is lagging behind its ASEAN neighbors in<br />

competitiveness surveys, even against newcomer Vietnam (Table 1-2). In the 2011 DBS, the<br />

Philippines and Thailand were the only ASEAN countries to decline in the rankings. Malaysia,<br />

Indonesia, and Vietnam all recorded improvements, with Vietnam outperforming all others with a<br />

jump from 93 in 2010 to 78 in 2011. The Philippines dropped four places from the previous year.<br />

Table 1-2<br />

Global Competitiveness Rankings of ASEAN Nations, 2011<br />

Survey Malaysia Thailand Indonesia Vietnam Philippines<br />

GCI, 2011-2012 21 39 46 65 75<br />

GCY, 2011 10 26 35 - 39<br />

DBS, 2011 21 19 121 78 148<br />

SOURCES: Compiled from WEF, IMD and DB survey 2011 Reports.<br />

How the Philippines performs in comparison with its ASEAN neighbors in starting a business,<br />

dealing with construction permits, and registering a property is shown in Table 1-3. The gap in<br />

rank between the Philippines and the other ASEAN countries is widest in dealing with<br />

construction permits and in registering property, where Thailand has so far been trailing only<br />

Singapore, which is the best performer in the region. The number of procedures followed in the<br />

Philippines is generally more than in its neighbors and the cost of securing the permit is higher.<br />

87<br />

(133)<br />

144<br />

(183)<br />

85<br />

(139)<br />

148<br />

(183)<br />

75<br />

(142)<br />

-

G LOBAL C OMPETITIVENESS AND <strong>BPLS</strong> STREAMLINING 3<br />

The country’s cumbersome process for business start up has proven to be a strong disincentive for<br />

entrepreneurs. Reducing the number of procedures will shorten processing time. Hence, to move<br />

closer to the ranking of its ASEAN neighbors, the Philippines must prioritize these two areas for<br />

reform. Using ASEAN as a benchmark is vital as it raises the bar for improving the Philippines’<br />

competitiveness.<br />

Table 1-3<br />

Ease of Doing Business for Select ASEAN Countries, 2010-2011<br />

Criteria Singapore Thailand Malaysia Vietnam Indonesia Philippines<br />

Ease of Doing Business (rank) 1 19 21 78 121 148<br />

1. Starting a business (rank) 4 95 113 100 155 156<br />

a. Procedures (number) 3 7 9 9 9 15<br />

b. Time (days) 3 32 17 44 47 38<br />

c. Cost (% of income per capita) 0.7 5.6 17.5 12.1 22.3 30.3<br />

d. Minimum Capital (% of Income) 0 0 0 0 53.1 6.0<br />

2. Dealing w/ construction permits<br />

(rank)<br />

SOURCE: Doing Business Survey, 2011,<br />

2 12 108 62 60 156<br />

One caveat about these surveys is that they are based on a combination of statistics and<br />

perception surveys that sometimes leads to puzzling results. On some indicators, the Philippines<br />

ends up ranking lower than we would like to believe. This tells us that perception (and<br />

communication to correct any misperception) is an element that does not receive enough attention<br />

(Luz 2011).<br />

1.3 NATIONAL SURVEYS ON COMPETITIVENESS<br />

Global surveys may be a good indicator of a country’s competitiveness, but many reforms critical<br />

to generating investment are needed at the sub-national level. This is especially so in the<br />

Philippines which has been decentralizing since 1991. The microeconomic foundation of<br />

competitiveness pertains not only to sectors but also to geographical development. Hence, the<br />

desire to improve competitiveness spurred the conduct of two city-level competitiveness surveys<br />

in 2011: the IFC’s Sub-<strong>National</strong> Doing Business Survey (SNDB) and the Philippine Cities<br />

Competitiveness Ranking Project (PCCRP). The Asian Institute of Management Policy <strong>Center</strong><br />

(APC) conducted both surveys.<br />

Sub-<strong>National</strong> Doing Business Survey<br />

Conducted in 2011 with support from USAID’s through the Local Implementation of <strong>National</strong><br />

Competitiveness for Economic Growth (LINC-EG) project, the SNDB is based on the DBS but<br />

covers only 3 of the 11 areas of business regulation that pertain to municipal and city<br />

governments, and where local differences exist (i.e., starting a business, dealing with construction<br />

permits, and registering property).

4 <strong>BPLS</strong> R EFORM P ROGRAM G UIDE<br />

According to the 2011 SNDB, a business applicant has to follow 15 to 22 steps to start a business<br />

in major cities, with Cebu City and Manila requiring the least number of steps (Table 1-4). The<br />

average number of steps in East Asia and the Pacific is 7.8, while the average number in member<br />

countries of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) is 5.6. 2 On<br />

average it takes 30 days to process applications in the Philippines but only 13.8 days in OECD<br />

countries. And, on average, the Philippines has only two fewer procedures than Equatorial<br />

Guinea, the country with the most procedures among the 183 countries surveyed (DGB 2011).<br />

Certainly this is not a salutary situation for the Philippines.<br />

Table 1-4<br />

Comparison of Philippine Cities in Processing Business Start-Ups<br />

Too many requirements to start a business<br />

SOURCE: Doing Business 2011: Making a Difference for Entrepreneurs.<br />

Financial & Private Sector Development<br />

2 The OECD has 34 member countries, mostly advanced economies with some emerging countries like<br />

Mexico, Chile and Turkey.

G LOBAL C OMPETITIVENESS AND <strong>BPLS</strong> STREAMLINING 5<br />

Local requirements for some cities add to the time it takes to start a business. Examples of these<br />

requirements include the notarization of the business permit applications and securing of<br />

environmental permits and location clearances. Some cities require the verification of real<br />

property tax payments (e.g., Cagayan de Oro, Lapu-Lapu and Mandaue), while others require a<br />

stamp of approval for the Certificate of Occupancy (i.e., Muntinlupa), or police clearance as in<br />

Zamboanga.<br />

In addition to local requirements, firms have to meet the requirements of <strong>National</strong> Government<br />

Agencies (NGAs). The <strong>National</strong> Internal Revenue Code and Bureau of Internal Revenue (BIR)<br />

require entrepreneurs to buy special accounting books, obtain authorization to print receipts, and<br />

have the printed receipts stamped by the BIR (Doing Business Philippines 2011).<br />

Philippine Cities Competitiveness Ranking Project<br />

Conducted by the APC since 1999, the Philippine Cities Competitiveness Ranking Project<br />

(PCCRP) is based on the IMD’s World Competitiveness Yearbook (WCY) and uses Michael<br />

Porter’s diamond theory as framework. The indicators used in the project are government<br />

efficiency, economic performance, business efficiency, and infrastructure. The 2009 PCCRP<br />

covered six competitiveness drivers, weighted as follows:<br />

1. Dynamism of the local economy (20 percent)<br />

2. Cost of doing business (15 percent)<br />

3. Infrastructure (17.5 percent)<br />

4. Responsiveness of the LGU to business needs (20 percent)<br />

5. Human resources and training (10 percent)<br />

6. Quality of life (17.5 percent).<br />

The 2011 PCCRP was supported by the German Agency for International Cooperation (GIZ) 3 ,<br />

USAID’s LINC-EG (APC 2009, 11-16) and other partners. It covers 29 cities categorized into the<br />

three groups on the basis of level of development: emergent cities, growth centers, and<br />

metropolitan growth centers. 4 Table 1-5 presents the top three cities in these categories. In the<br />

overall standings, Cebu City, Cagayan de Oro, Dagupan City ranked the highest in their<br />

respective categories.<br />

In the PCCRP, the complexity of business registration is reflected in the criterion of<br />

“responsiveness of city government to business needs,” which has a weight of 20 percent. There<br />

are five subcategories under this criterion, one of which pertains to the “degree of ease of doing<br />

business,” which is measured by (1) the length of time to renew business permits and (2) rating of<br />

the process and procedures for renewing business permits. The former is based on hard data while<br />

the latter is based on perception. By this criterion, the cities that ranked the highest were Davao,<br />

Bacolod, and Tacloban.<br />

3 Formerly the German Agency for Technical Cooperation (GTZ).<br />

4 Levels of development were measured on the basis of population and income (excluding internal revenue<br />

allotment).

6 <strong>BPLS</strong> R EFORM P ROGRAM G UIDE<br />

Table 1-5<br />

Top Three Ranked Cities in the PCCRP, 2009<br />

City<br />

Overall<br />

Rank<br />

Dynamism<br />

of Local<br />

Economy<br />

(20%)<br />

Cost of<br />

Doing<br />

Business<br />

(15%)<br />

Ranking according to PPCRP Criteria<br />

Infrastructure<br />

(17.5%)<br />

Human<br />

Resources<br />

Training<br />

(10%)<br />

M ETROPOLITAN G ROWTH C ENTERS<br />

LGU<br />

Responsiveness<br />

(20%)<br />

Cebu 1 1 2 1 1 2 2<br />

Davao 2 2 1 2 2 1 1<br />

G ROWTH C ENTERS<br />

Cagayan de Oro 1 1 3 2 3 3 3<br />

Bacolod 2 5 6 7 3 1 2<br />

Zamboanga 3 7 1 4 3 6 5<br />

E MERGENT C ITIES<br />

Dagupan 1 7 5 1 11 2 5<br />

Tacloban 2 8 13 10 1 1 5<br />

San Fernando 3 9 2 3 6 3 1<br />

SOURCE: AIM. 2010 Cities and enterprises, Competitiveness and Growth: Philippine Cities Competitiveness Ranking 2009.<br />

Quality<br />

of Life<br />

(17.5%)<br />

1.4 AWARDS AND INCENTIVES<br />

Awards are given to motivate local governments to make the reforms necessary to attract<br />

investment. The Philippine Chamber of Commerce and Industry (PCCI) sponsors the annual<br />

Most Business-Friendly Local Government Units (LGUs) Award, which complements the<br />

national government initiative to benchmark outstanding reforms in governance that promote<br />

local trade and investment and ensure accountability, transparency, and efficiency in public<br />

service. There are two levels of award. Level One covers all highly urbanized cities and higher<br />

income LGUs (1 st to 3 rd class), while Level Two includes lower income LGUs (4 th to 6 th class). In<br />

2010 winners were selected on the basis of self-assessment reports and interviews conducted by a<br />

distinguished panel of judges chaired by former Senator Aquilino Pimentel Jr. Winners received a<br />

certificate of donation for one school building from officers of the Federation of Filipino-Chinese<br />

Chamber of Commerce and Industry, Inc.<br />

In the 36th Philippine Business Conference in 2010, five LGUs received awards for being<br />

business-friendly:<br />

1. City of San Fernando, Pampanga (city level 1)<br />

2. Candon City, Ilocos Sur (city level 2)<br />

3. Municipality of Carmona, Cavite (municipal level 1)<br />

4. Municipality of Guimbal, Iloilo ( municipal level 2)<br />

5. Leyte for (province level 1).<br />

Six LGUs received special citations for outstanding efforts in each of the award criteria:<br />

1. La Union Province - trade, tourism and investment promotions

G LOBAL C OMPETITIVENESS AND <strong>BPLS</strong> STREAMLINING 7<br />

2. Talavera, Nueva Ecija - quality customer service<br />

3. San Nicolas, Ilocos Norte - public-private sector partnership<br />

4. Tarlac - micro, small, and medium enterprise development<br />

5. Olongapo - investment promotions<br />

6. Pangasinan - quality management and systems innovation.<br />

Another incentive is the EXCELL Awards, a project of Department of the Interior and Local<br />

Government (DILG) Region 6 to recognize the best managed local governments in the region.<br />

Awardees follow best practices and demonstrate achievements and innovations in governance,<br />

administration, social services, economic development, environmental management, and local<br />

legislation. The project also aims to advocate for transparency and accountability in governance,<br />

reinforce good performance, popularize replicable best practices, and identify interventions to<br />

improve LGU performance. Each major awardee receives P50,000 and special awardees each<br />

receive P10,000.<br />

The 2010 awardees were as follows:<br />

1. Negros Occidental—best performing province and all special awards in the provincial<br />

category<br />

2. San Carlos City—Negros Occidental best performing city and excellence in<br />

environmental management, economic development, social services<br />

3. Oton, Iloilo—best performing 1st to 3rd class municipality and excellence in local<br />

legislation<br />

4. Anilao, Iloilo—best performing 4th to 6th class municipality and excellence in local<br />

legislation, administrative governance, social services.<br />

Special awardees were as follows:<br />

1. Bacolod City and Kabankalan City—excellence in local legislation (city category)<br />

2. San Jose de Buenavista, Antique and Iloilo City—excellence in administrative<br />

governance for 1st to 3rd class municipalities and cities, respectively<br />

3. Miagao, Iloilo—excellence in social services 1st to 3rd class municipalities<br />

4. Miagao, Iloilo and Guimbal, Iloilo —excellence in economic development for 1st to 3rd<br />

class and 4th to 6th class municipalities, respectively<br />

5. Panay, Capiz and Guimbal, Iloilo—excellence in environmental management for 1st to<br />

3rd class and 4th to 6th class municipalities, respectively.

2. Understanding <strong>BPLS</strong><br />

<strong>Reform</strong>s<br />

2.1 WHAT IS <strong>BPLS</strong> STREAMLINING?<br />

Streamlining the business permitting and licensing system (<strong>BPLS</strong>) means implementing<br />

systematic and purposeful interventions to ease business start-up (e.g., simplifying registration<br />

process by reducing the number of steps and procedures and reducing processing times and cost).<br />

Streamlining can accelerate revenue mobilization, improve expenditure management, and<br />

increase access to finance for better service delivery and growth promotion.<br />

As shown in Figure 2-1, complying with the requirements of NGAs directly affects LGU<br />

processes. Such requirements include approval of business name registration by the Department<br />

of Trade and Industry (DTI) for single proprietorships, by the Securities and Exchange<br />

Corporation (SEC) for corporations, and by the Cooperative Development Authority (CDA) for<br />

cooperatives. During the renewal period, applicants must also obtain certifications from social<br />

security agencies. Streamlining must therefore happen at the national as well as the local level.<br />

However, for the purposes of this paper, we will focus on local <strong>BPLS</strong> reforms.<br />

Figure 2-1<br />

Macro-View of <strong>BPLS</strong> Processes<br />

NGA<br />

DTI, SEC, CDA<br />

Business name,<br />

BIR registration<br />

LGU<br />

BPLO<br />

Taxes,<br />

Clearances,<br />

Fees,<br />

Mayor’s Permit<br />

NGA<br />

SSS, PHILHEALTH<br />

Registration for<br />

medical insurance<br />

and social security

10 <strong>BPLS</strong> R EFORM P ROGRAM G UIDE<br />

2.2 LEGAL BASIS FOR <strong>BPLS</strong> REFORMS<br />

The policy platform for <strong>BPLS</strong> streamlining dates back to the 1990s. Republic Act 7470, signed in<br />

1992, created the <strong>National</strong> Economic Research and Business Assistance <strong>Center</strong> (NERBAC),<br />

which was envisioned as a center to “facilitate the processing of all government requirements<br />

necessary for the establishment of a business.” This directive was the basis for organizing<br />

NERBACs as registration centers that help applicants meet requirements for business start-ups.<br />

The momentum for <strong>BPLS</strong> reforms started in earnest during the term of then-President<br />

Macapagal-Arroyo. In her first State of the Nation Address in 2001, she directed national<br />

government agencies to reduce red tape by cutting in half the number of signatures required for<br />

their services. For LGUs, her message was “to streamline their operations, slash red tape. There<br />

must be continuity between the national and local governments in their efforts to be investorfriendly.”<br />

DTI Region 3 took this directive seriously and began streamlining business registration<br />

procedures (see <strong>BPLS</strong> Initiatives Between 2001–2010 ). Two years later, on September 15, 2003,<br />

Memorandum Order No. 117 was issued. It mandated local authorities to simplify and rationalize<br />

their civil application systems and for the Secretaries of DILG and DTI to facilitate the<br />

streamlining of procedures for permits and licenses, particularly business permits, building<br />

permits, certificates of occupancy, and other clearances.<br />

But the legal basis for the current <strong>BPLS</strong> reform program is RA 9485 or the Anti-Red Tape Act<br />

(ARTA) of 2007. In compliance with the Philippine Constitution provision that calls for<br />

simplifying government services, ARTA requires government instrumentalities and LGUs to<br />

deliver public services efficiently by reducing red tape. It identifies five aspects of service to be<br />

simplified: (1) steps in providing the service, (2) forms used, (3) requirements, (4) processing<br />

time, and (5) fees and charges. It also limits the number of signatories to five per request,<br />

application, or transaction and provides legal sanctions for noncompliance with the standards.<br />

Since the passage of ARTA, there have been a number of government policy issuances on <strong>BPLS</strong><br />

reforms. Joint Memorandum Circular No. 01 Series of 2009 (JMC 2009) was signed on February<br />

18, 2010 by the DILG, DTI, the Department of Public Works and Highways, the Social Security<br />

System and the mayors of the <strong>National</strong> Capital Region (NCR). It requires “all LGUs to undertake<br />

a reengineering of their transaction systems, including time and motion studies, and mandates<br />

each LGU to prepare a Citizen’s Charter which will contain their respective service standards.”<br />

The JMC was the first attempt to standardize registration procedures at the NCR for new business<br />

applications. Its recommendations were formulated by a Technical Working Group organized by<br />

the League of Cities of the Philippines (LCP) consisting of the Business Permits and Licensing<br />

Officers (BPLOs) of the NCR. This circular was superseded by two policies signed on August 6,<br />

2010:<br />

• The DTI-DILG Joint Memorandum Circular No. 1, series of 2010 on the “<strong>Guide</strong>lines in<br />

Implementing the Standards in Processing Business Permits and Licenses in All Cities<br />

and Municipalities” (JMC 2010).<br />

• The Joint DTI-DILG Department Administrative Order No. 1, series of 2010 on the<br />

“<strong>Guide</strong>lines in Implementing the Nationwide Upscaling of <strong>Reform</strong>s in Processing<br />

Business Permits and Licenses in all Cities and Municipalities in the Philippines<br />

(JDAO).”

U NDERSTANDING <strong>BPLS</strong> R E FORMS 11<br />

The first circular is a landmark directive that sets standards for processing new applications and<br />

renewals consistent with ARTA. To ensure implementation of these standards, the second circular<br />

defines institutional support for the reforms by specifying the roles of DTI and DILG. It also<br />

organizes national and local committees to oversee the reform process.<br />

On January 31, 2011, the DILG issued a supplementary memorandum to further streamline<br />

<strong>BPLS</strong>. Memorandum Circular No. 2011-15 reiterates the basis for setting business fees and the<br />

issuance of conditional business permits in cases where the only lacking requirements are those of<br />

the social security agencies.<br />

2.3 THE GOVERNMENT <strong>BPLS</strong> PROGRAM<br />

<strong>BPLS</strong> streamlining as a government program began in 2009 when the DILG and DTI convened<br />

two working groups under the Philippine Development Forum (PDF): the working group on<br />

decentralization and local government (DLG) and the working group on growth and investment<br />

climate (GIC). Initially, the program was to streamline <strong>BPLS</strong> in as many LGUs as possible. But<br />

to do this the program had to<br />

• Set service standards for <strong>BPLS</strong> that LGUs can follow,<br />

• Develop and implement capacity building programs for LGUs as they streamline their<br />

business registration systems,<br />

• Organize government departments at the regional level to work with LGUs in<br />

implementing the <strong>BPLS</strong> reforms, and<br />

• Harmonize development partners’ reform initiatives on <strong>BPLS</strong> streamlining.<br />

This project laid the groundwork for scaling up reforms in 2010. When the new administration<br />

took over in 2010, no less than President Benigno Aquino III called on LGUs to “look for more<br />

ways to streamline our processes to make business start-ups easier.” Responding to this call, the<br />

DTI and the DILG scaled up the program and launched the Nationwide Streamlining of Business<br />

Permits and Licensing Systems (<strong>BPLS</strong>) <strong>Program</strong> on August 6, 2010, with the signing of the JMC<br />

2010. Hence, <strong>BPLS</strong> streamlining is associated with compliance with the service standards set in<br />

the JMC for processing business registration applications.<br />

<strong>Program</strong> Components<br />

The government’s <strong>BPLS</strong> program has five components, which are described below.<br />

Component 0: Mobilizing Champions for the <strong>BPLS</strong> <strong>Reform</strong> Process<br />

Implementing reforms requires securing the support of various sectors of society, namely:<br />

• Local chief executives. As reform implementers, it is important that LCEs act as local<br />

champions and provide financial and manpower support for the program.<br />

• LGU leagues. <strong>BPLS</strong> reforms involve cities and municipalities that issue the Mayor’s<br />

permits. Support from the League of Cities of the Philippines (LCP) and the League of<br />

Municipalities of the Philippines (LMP) is needed to encourage their respective members<br />

to participate in the program. These leagues can also provide capacity building support to

12 <strong>BPLS</strong> R EFORM P ROGRAM G UIDE<br />

members as the LMP did through its Electronic Governance for Municipal Development<br />

(eGov4MD) project.<br />

• Private sector. <strong>National</strong> and local businesses, academia, and civil society organizations<br />

are important contributors to reform processes. As major beneficiaries of reforms, private<br />

business groups will be encouraged to monitor the progress of the program and<br />

participate as service providers to assist LGUs in the reform process.<br />

• Concerned NGAs and their regional offices. The <strong>BPLS</strong> process involves securing permits<br />

from NGAs, so it is important that these agencies streamline their own processes, provide<br />

manpower support to LGUs’ business one-stop shops (BOSS), and provide coaching<br />

assistance to LGUs during the reform process.<br />

• Development partners. Support is needed from development partners to scale up the<br />

<strong>BPLS</strong> reforms and conduct studies for the next wave of process streamlining.<br />

Component 1: Simplification and Standardization of the <strong>BPLS</strong> Process<br />

Using the ARTA as a framework, <strong>BPLS</strong> streamlining starts with process re-engineering that will<br />

enable LGUs to meet four service standards in processing registration applications: (1) use one<br />

application form; (2) limit the number of signatories; (3) reduce the number of steps; and (4)<br />

speed up processing time (see Performance Standards for a more detailed discussion of<br />

standards).<br />

Component 2: <strong>Computer</strong>ization of the <strong>BPLS</strong> Process<br />

Efficient re-engineering requires some form of computerization. Government is encouraging<br />

LGUs to use information technology in streamlining <strong>BPLS</strong>. Existing <strong>BPLS</strong> software includes<br />

programs widely promoted by government (e.g., e-<strong>BPLS</strong> by the <strong>National</strong> <strong>Computer</strong> <strong>Center</strong><br />

(NCC2). With the new <strong>BPLS</strong> standards in place, government intends to redevelop e-<strong>BPLS</strong> and<br />

will review <strong>BPLS</strong> software now in the market. The objective is to assist LGUs in choosing<br />

appropriate IT solutions for streamlined <strong>BPLS</strong> processes. The NCC2 is taking the lead in this<br />

component.<br />

Component 3: Institutionalization of <strong>BPLS</strong> <strong>Reform</strong>s<br />

To ensure the sustainability of <strong>BPLS</strong> reforms, legal instruments such as local regulations should<br />

be issued to support the streamlined processes. Otherwise, every change in administration will<br />

lead to a return to old practices. The government will therefore assist in (1) setting up a<br />

monitoring and evaluation system at the LGU and at the regional and the national offices of DTI<br />

and DILG; (2) organizing local business chambers and civil society organizations for process<br />

improvements and monitoring; (3) enjoining LGUs to work for International Organization for<br />

Standardization (ISO) certification of their <strong>BPLS</strong>; and (4) developing incentive systems to<br />

promote best practices.<br />

Component 4: Improvements in Customer Relations<br />

The <strong>BPLS</strong> program also addresses complaints of poor service in the permitting process. Hence,<br />

after the LGUs have completed process re-engineering, they are encouraged to keep improving<br />

how they deal with the public. This entails complying with consumer protection laws, such as the<br />

Anti-Fixing Act; setting up a complaints desk; and implementing the Citizens’ Charter. Other

U NDERSTANDING <strong>BPLS</strong> R E FORMS 13<br />

areas of reform that can lead to a more customer-friendly <strong>BPLS</strong> include establishing Business<br />

One-Stop Shops (BOSS); conducting information, education, and communication campaigns; and<br />

training LGU staff in customer relations.<br />

Performance Standards<br />

The most significant policy pronouncement in this decade on <strong>BPLS</strong> reform may well be JMC<br />

2010 because it established the service standards against which LGU performance in <strong>BPLS</strong><br />

reforms can be measured. JMC 2010 stipulates four performance standards for business<br />

registration: (1) use of a unified registration form, (2) limit on the number of steps that an<br />

applicant must take in applying for a permit, (3) limit on the processing time, and (4) limit on the<br />

number of signatories.<br />

Unified Business Registration Form<br />

An LGU must issue the Unified Business Registration Form (see Appendix A. <strong>BPLS</strong> Unified<br />

Form). That form contains all information and approvals needed for registration and facilitates<br />

exchange of information among LGUs and NGAs. In the past, every department in the LGU<br />

required applicants to fill out separate forms. The unified form was developed by a technical<br />

working group organized by the LCP. It is based on the form used by the Philippine Business<br />

Registry (PBR), a project of the DTI that aims to centralize data from NGAs involved in business<br />

registration (e.g., DTI, BIR, Securities and Exchange Commission, and the social security<br />

agencies).<br />

Standard Steps<br />

JMC 2010 enjoins cities and municipalities to ensure that applicants follow five steps in securing<br />

a mayor’s permit, whether for new applications or for business renewals:<br />

1. Get an application form from the city or municipality.<br />

2. File or submit the filled in form with required documents attached.<br />

3. Undergo one-time assessment of taxes, fees, and charges.<br />

4. Make one-time payment of taxes, fees, and charges.<br />

5. Secure the mayor’s permit.<br />

To be able to comply with these standard steps, JMC 2010 also recommends that LGUs adopt the<br />

following measures:<br />

• Conduct inspections in accordance with zoning and environment ordinances and<br />

building and fire safety, and health and sanitation regulations, which have been<br />

undertaken during the construction stage, within the year since issuance of the business<br />

permit.<br />

• Organize joint inspection teams (JIT) composed of the BPLO, the city/municipal<br />

engineer, the city/municipal health officer or representative, the city/municipal planning<br />

officer or designated zoning officer, the city/municipal environment and natural resources<br />

officer or representative, the city/municipal treasurer, and the city/municipal fire marshal.

14 <strong>BPLS</strong> R EFORM P ROGRAM G UIDE<br />

• Forge a memorandum of agreement between the Bureau of Fire Protection (BFP) and the<br />

city/municipality, as necessary, to implement streamlined procedures for assessing and<br />

paying fire safety inspection fees that will enable the LGUs to implement the steps above.<br />

In addition, DILG Memorandum Circular No. 2011-15 encourages LGUs to issue a conditional<br />

permit to a business in cases where the “only lacking clearances are those of the SSS, Phil Health<br />

and PAG-IBIG, conditional upon the submission of the clearances after one month and the<br />

revocation or non-renewal of a business permit for failure to do so."<br />

Standard Processing Time<br />

Consistent with ARTA, cities and municipalities are enjoined to comply with prescribed times for<br />

processing and releasing business registrations:<br />

• Process and release new business permits in 10 days. LGUs are encouraged to strive for<br />

5 days or less, which is the average processing time in LGUs with streamlined <strong>BPLS</strong>.<br />

This processing is classified as a complex transaction following ARTA.<br />

• Process and release business renewals in 5 days. LGUs are encouraged to strive for one<br />

day or less, which has been achieved in many LGUs that have streamlined their <strong>BPLS</strong>.<br />

This processing is classified as a simple transaction.<br />

Signatories<br />

Cities and municipalities shall follow the prescribed number of signatories required in processing<br />

new business applications and business renewals based on the provisions of the ARTA, which<br />

limits the number of signatures in any document to five. However, LGUs are encouraged to<br />

require only two signatories, the Mayor and the Treasurer or the BPLO. To avoid delay in the<br />

release of permits, the Mayor may deputize alternate signatories (e.g., the Municipal or City<br />

Administrator or the BPLO).<br />

Proposed <strong>BPLS</strong> Procedures<br />

DTI and DILG have produced a manual that details the steps that LGUs may follow in<br />

streamlining <strong>BPLS</strong>. These steps include the following:<br />

1. Pre-streamlining Activities. These activities solicit the support of stakeholders and the<br />

commitment of LCEs for the reforms. They consist of conducting orientation workshops<br />

on the reforms, securing the commitment of LCEs to making the reforms, and organizing<br />

technical working groups to make the reforms.<br />

2. Diagnosis. This step is usually taken in “self-assessment" workshops in which the LGU<br />

(1) creates a current <strong>BPLS</strong> flowchart for new registrations and renewals, (2) assesses the<br />

process vis-a-vis the standards set by government, and (3) identifies gaps and strategies<br />

for bridging the gaps.<br />

3. Process Design. This step involves preparing the <strong>BPLS</strong> action or reform plan, which<br />

assigns responsible persons and defines budget requirements for the reforms.<br />

4. Institutionalization. This step ensures that the legal requisites for the reforms (e.g.,<br />

executive orders and ordinances) are prepared and legislated at the local level.

U NDERSTANDING <strong>BPLS</strong> R E FORMS 15<br />

5. Implementation. Implementation starts with preparation of the work plan and financial<br />

plan, and dry-runs of the streamlined process.<br />

6. Sustaining <strong>Reform</strong>s. Ensuring the sustainability of reforms involves setting up a<br />

monitoring system that includes client satisfaction surveys and engages stakeholders,<br />

such as local business chambers and civil society groups, to monitor LGU compliance<br />

with reforms. The more progressive LGUs have sought ISO certification for their <strong>BPLS</strong>.<br />

Target LGUs<br />

While all cities and municipalities are enjoined to streamline their <strong>BPLS</strong>, not all LGUs can be<br />

assisted with streamlining due to limited resources. Hence, it was agreed that the program will<br />

assist only a critical mass of LGUs. An LGU will be included on the basis of<br />

• The number of business establishments in the LGU.<br />

• The LGU’s investment potential, especially in relation to the government’s four priority<br />

sectors of 2009 (i.e., agribusiness, tourism, business process outsourcing and information<br />

technology (BPO-IT), and mining).<br />

• The LGU's being on the list of 120 “sparkplugs” identified by NCC1.<br />

• The LGU's inclusion in the government’s commitments to the Millennium Challenge<br />

Corporation.<br />

• The LGU’s being a recipient of projects in the development community.<br />

LGUs will not be automatically enrolled in the program unless (1) the LCE has expressed<br />

willingness to undertake the reform considering the investments associated with the program; and<br />

(2) there is private sector commitment in the locality to participate in the reform process.<br />

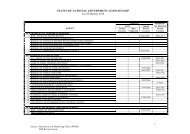

Figure 2-2 lists the coverage of the program according to levels of LGUs. Level 1 refers to the 17<br />

highly urbanized cities/municipalities in the NCR, most of which have streamlined BPLs. Level 2<br />

refers to LGUs with the most business establishments (excluding NCR), those identified by<br />

national government agencies as having good potential for attracting in the four priority sectors,<br />

and those named in the country's commitment to the Millennium Challenge Corporation. Level 3<br />

refers to LGUs not in Levels 1 and 2 but in the 120 "sparkplug” list. Level 4 refers to LGUs with<br />

ODA on <strong>BPLS</strong> streamlining. Level 5 refers to all remaining cities and municipalities.<br />

The government has identified 480 cities and municipalities in the <strong>BPLS</strong> program (Table 2-1).<br />

Originally, government support through capacity building and coaching assistance was limited to<br />

480 LGUs, mostly from Levels 1-3 and some in Level 4, which were expected to be fully<br />

compliant with the BPLs standards by 2014. The program, however, has been fast tracked in<br />

2011, with 2012 targeted as the program completion year.

16 <strong>BPLS</strong> R EFORM P ROGRAM G UIDE<br />

Figure 2-2<br />

<strong>BPLS</strong> Streamlining <strong>Program</strong> Coverage by LGU Level<br />

Level 1<br />

NCR LGUs<br />

(16 Cities, 1<br />

Municipality)<br />

Proposed Coverage of <strong>BPLS</strong> Streamlining<br />

Level 2<br />

High density of<br />

businesses<br />

Sector Priorities in<br />

BPO-IT, Tourism,<br />

Agribusiness &<br />

Mining<br />

LGUs included in<br />

the MCC<br />

commitments<br />

Targeted Assistance<br />

By Government<br />

Level 3<br />

Remaining LGUs<br />

from NCC List of<br />

120 Sparkplug<br />

LGUs not covered<br />

in Levels 1 & 2<br />

Level 4<br />

LGUs with existing<br />

ODA projects<br />

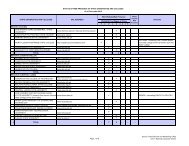

Table 2-1<br />

Regional Allocation of Cities and Municipalities in the <strong>BPLS</strong> <strong>Program</strong><br />

By Enrollment<br />

Level 5<br />

All other LGUs<br />

Region 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 Total<br />

NCR 1 1<br />

CAR 3 3<br />

1 8 6 14<br />

2 3 2 2 2 9<br />

3 23 26 29 29 23 130<br />

4A 16 25 31 35 35 142<br />

4B 5 4 5 14<br />

5 6 2 1 2 11<br />

6 6 3 3 2 4 18<br />

7 9 17 2 1 29<br />

8 4 4 9 6 8 31<br />

9 4 4 8<br />

10 4 4 4 12<br />

11 7 1 5 5 2 20<br />

12 7 4 12 9 32<br />

13 2 3 1 6<br />

Total 108 103 98 90 81 480

U NDERSTANDING <strong>BPLS</strong> R E FORMS 17<br />

Government Assistance to LGUs<br />

The government identified the following assistance packages to LGUs (outside of NCR) that<br />

would like to streamline their <strong>BPLS</strong>:<br />

• Self-Assessment Workshop. DTI and DILG will join forces to assist LGUs in conducting<br />

a workshop to document and assess their current system in relation to standards and to<br />

propose reforms for presentation to the mayor. Participation will be by enrollment and<br />

expenses will be borne by the LGUs. Appendix B. Assessing Business Processes details<br />

steps for assessing the <strong>BPLS</strong> process of LGUs and preparing a reform action program.<br />

• Technical Assistance Services. The DTI and DILG will organize “coaching” teams from<br />

the government, BPLOs, and the private sector to assist LGUs in implementing their<br />

<strong>BPLS</strong> streamlining plans.<br />

• Automation (<strong>Computer</strong>-Aided) <strong>BPLS</strong>. LGUs interested in automating their <strong>BPLS</strong> will be<br />

assisted in acquiring the e-<strong>BPLS</strong> software and related training. The <strong>National</strong> <strong>Computer</strong><br />

<strong>Center</strong> (NCC2) has drafted guidelines on <strong>BPLS</strong> computerization that will soon be<br />

disseminated to interested LGUs. It is planning to redevelop e-<strong>BPLS</strong> and create a system<br />

of accreditation for private software developers who will be producing <strong>BPLS</strong> solutions<br />

for LGUs.<br />

2.4 INSTITUTIONAL STRUCTURES AND MECHANISMS<br />

As streamlining experiences accumulate, structures that ensure proper and prompt<br />

implementation of reforms will be needed. At the same time, support for reforms from different<br />

stakeholders is critical to the success of the project. This is articulated in Component 0 of the<br />

government program on <strong>BPLS</strong>.<br />

<strong>National</strong> Structures and Mechanisms<br />

Two groups promote reforms in business registration. The <strong>BPLS</strong> Oversight Committee (BOC),<br />

which is co-chaired by DTI and DILG, was organized under the Philippine Development Forum.<br />

The Working Group on Transaction Costs and Flows (TCF) is under the <strong>National</strong><br />

Competitiveness Council (NCC1). Figure 2-3 shows the links between these committees.<br />

<strong>BPLS</strong> Oversight Committee<br />

The BOC is directly responsible for managing <strong>BPLS</strong> reforms. It was organized in June 2010 and<br />

officially established on August 6, 2011 through JMC 2010. As stated in the JDAO, the BOC is<br />

to (1) oversee implementation of nationwide scaling up of <strong>BPLS</strong> reform, particularly service<br />

standards; (2) mobilize resources for implementation of various components of <strong>BPLS</strong> reforms;<br />

(3) coordinate various initiatives of government, the private sector and the development<br />

community on <strong>BPLS</strong> reforms; (4) assist national government agencies, DTI, SEC, SSS, Phil<br />

Health, Bureau of Fire Protection in streamlining procedures; (5) assist government in building<br />

the capacity of governments to implement the <strong>BPLS</strong> reforms; and (6) ensure that <strong>BPLS</strong> reforms<br />

are aligned with other reforms that enhance the competitiveness of the country and LGUs.

18 <strong>BPLS</strong> R EFORM P ROGRAM G UIDE<br />

Figure 2-3<br />

Institutional Support for <strong>BPLS</strong> <strong>Reform</strong>s<br />

Philippine Development Forum<br />

Working Group on<br />

Growth & Investment<br />

Climate<br />

Conveners: DTI & IFC<br />

Conveners: DOF & WB<br />

Sub Working Group in Local<br />

Investment <strong>Reform</strong>s<br />

Conveners: DTI, DILG &<br />

USAID<br />

<strong>BPLS</strong> Oversight Committee<br />

Co-Chairs: DTI & DILG<br />

<strong>BPLS</strong> Coordinator Committee<br />

Co-Chairs: DTI & DILG<br />

Regional Directors<br />

Working Group on<br />

Decentralization &<br />

Local Government<br />

Conveners: DILG & WB<br />

<strong>National</strong> Competitiveness Council<br />

Chairs: DTI Secretary & Private Sector<br />

Representative<br />

Education & Human<br />

Resources Anti-Corruption<br />

Performance<br />

Governance System<br />

I.T. Governance<br />

System<br />

Infrastructure for<br />

Competitiveness Judicial System<br />

Transaction Costs &<br />

Flows<br />

Chairs: DTI<br />

Competitive<br />

Agriculture<br />

Transparency in<br />

Budget Delivery Power and Energy<br />

Following the PDF structure, the BOC includes development partners. Composed of the LGU<br />

Leagues (LCP and LMP), NCC1, NCC2, and USAID, GIZ, IFC and the Spanish Agency for<br />

International Development Cooperation (AECID), the BOC plans and implements <strong>BPLS</strong>-related<br />

activities. In 2010, it organized a multidonor project that trained DTI and DILG coaches who<br />

have been rolling-out reforms to the targeted LGUs. The BOC has been proposed to be subsumed<br />

as a committee under the Sub-Working Group on Local Investment <strong>Reform</strong>s, a new group under<br />

the working groups on decentralization and local government and growth and investments.<br />

BOC’s 2011 work plan includes (1) stepping up the LGUs that have streamlined to the<br />

automation level; (2) ensuring the completion of process re-engineering of LGUs now making<br />

<strong>BPLS</strong> reforms; (3) establishing an effective monitoring and evaluation system; (4) building a<br />

<strong>BPLS</strong> advocacy and marketing program; and (5) establishing a <strong>BPLS</strong> certification system.<br />

<strong>National</strong> Competitiveness Council<br />

Chaired by the DTI Secretary and co-chaired by a private sector representative, NCC1 supports<br />

the BOC through its Transaction Costs and Flows (TCF) working group, also co-chaired by a DTI<br />

undersecretary and a private sector representative. NCC1 was reconstituted through Executive<br />

Order 44 issued on June 3, 2011. It is the primary collection point of investor issues that need to<br />

be addressed to improve the country's competitiveness in industry, services, and agriculture;<br />

advises the President on policy matters affecting business competitiveness; and provides input to<br />

the Philippine Development Plan, the Philippine Investments Priority Plan (PIPP), and the<br />

Philippine Exports Priority Plan (PEPP). Its members include the Secretaries of Finance, Energy

U NDERSTANDING <strong>BPLS</strong> R E FORMS 19<br />

and Tourism, and Education, the Director-General of <strong>National</strong> Economic Development Authority<br />

(NEDA), and five private sector representatives.<br />

Even before its recent reorganization, NCC1 was active in <strong>BPLS</strong> reforms, focusing on monitoring<br />

and influencing the NGAs to streamline <strong>BPLS</strong> processes. For instance, the TCF focused on the<br />

use of a common database and application form for the social security agencies. It has also<br />

examined the permitting processes of agencies giving special permits to business enterprises (e.g.,<br />

environment clearance certificate of the Department of Environment and Natural Resources.<br />

In 2011, NCC1 plans to support BOC initiatives by (1) showcasing successful reformers in road<br />

shows in seven regions; (2) designing a <strong>BPLS</strong> customer satisfaction survey to be conducted in<br />

early 2012 to validate LGUs’ reforms; and (3) providing training for LGU front liners on service<br />

excellence and values reorientation.<br />

Local Institutions and Mechanisms<br />

The <strong>BPLS</strong> Coordination Committee (BCC) is the local counterpart of the BOC mandated in the<br />

JDAO of August 6, 2010. The BCC is co-chaired by the regional directors of the DILG and DTI<br />

and consists of local chambers, the LGUs, and academics. Following the JDAO, the BCC’s<br />

functions include<br />

• Providing direction in implementing <strong>BPLS</strong> reforms at the local level.<br />

• Organizing training for priority LGUs that will be streamlining the <strong>BPLS</strong>.<br />

• Organizing a pool of <strong>BPLS</strong> trainers in the region (from the BPLOs of LGUs, the<br />

academic community, and the local chamber) that can be tapped to coach LGUs in<br />

streamlining registration processes.<br />

• Monitoring LGU compliance with <strong>BPLS</strong> standards.<br />

• Soliciting support from the private sector.<br />

• Liaising with the <strong>National</strong> BOC on implementation of <strong>BPLS</strong> reforms.<br />

The BCCs have been responsible for organizing the roll-out of <strong>BPLS</strong> standards to targeted LGUs.<br />

Action plans for the 2011 roll-out were in fact prepared by the regional BCCs and submitted to<br />

DTI and DILG.

3. Past <strong>BPLS</strong> <strong>Reform</strong>s in the<br />

Philippines<br />

In the Philippines, the government has only recently been deeply engaged in business registration<br />

reform, but reform efforts can be traced back over the past 10 years. Those efforts offer valuable<br />

lessons in governance and development for the current <strong>BPLS</strong> program of DTI and DILG. The<br />

program can be considered a model of convergence and coordination among government<br />

agencies, and of the harmonization of official development assistance, following the principles of<br />

aid effectiveness (OECD 2005/2008).<br />

Business registration reform began through the uncoordinated and independent efforts of various<br />

entities. A good deal of <strong>BPLS</strong> reform was pursued through donor-supported projects focused on<br />

transparent and accountable governance, decentralization, local economic development, small<br />

enterprise promotion, and private sector participation. Some LGUs initiated and funded their own<br />

registration reform; others were prodded by the regional offices of government agencies.<br />

<strong>Reform</strong>s were made in Luzon, Visayas, and Mindanao without the benefit of service standards,<br />

which were not put in place until the formal launch of the nationwide <strong>BPLS</strong> streamlining program<br />

in August 2010. A chronological account of <strong>BPLS</strong> reforms is in Appendix C; various <strong>BPLS</strong><br />

projects of the past ten years are summarized below.<br />

3.1 <strong>BPLS</strong> INITIATIVES BETWEEN 2001–2010<br />

There have been a number of significant programs to simplify business registration procedures<br />

since 2001. Most were conducted through development assistance projects and spanned the<br />

different island groupings of the country. These programs paved the way for the formulation of<br />

extensive scaling up of business registration reforms in 2010.<br />

<strong>BPLS</strong> <strong>Reform</strong>s in Central Luzon, 2001<br />

In 2001, the Central Luzon Investment Promotion <strong>Center</strong> Region 3 (CLIPC) and the provincial<br />

offices of DTI Region 3, DILG, and LGUs campaigned to simplify business licensing 5 in<br />

response to the state of the nation address of then-President Macapagal-Arroyo. On November<br />

23, 2001, <strong>BPLS</strong> reform was adopted as a flagship project of the Central Luzon Coordinating<br />

Council (CLICC). The Region 3 initiative was driven by provincial governors on the Central<br />

5 This discussion is based on a presentation by Judith Angeles (2009), Streamlining the Business Processes<br />

in the Issuance of Mayor’s permit in Central Luzon.

22 <strong>BPLS</strong> R EFORM P ROGRAM G UIDE<br />

Luzon Growth Corridor Foundation Inc. (CLGCFI). On March 22, 2002, a memorandum of<br />

commitment on “implementation of the streamlined business processes of critical frontline<br />

services in Central Luzon’s W Growth Corridor” was signed and eight municipalities committed<br />

to streamlining the issuance of their mayor’s permit: Balanga City in Bataan; Sta. Maria &<br />

Meycauyan in Bulacan; San Jose & Cabanatuan cities Nueva Ecija; Angeles City in Pampanga;<br />

Tarlac City in Tarlac; and Olongapo City in Zambales.<br />

Memorandum Circular 117 of 2003 provided impetus for the region to accelerate streamlining. Its<br />

program enjoined LGUs to (1) establish internal monitoring systems and internal audits, (2)<br />

establish a BOSS, and (3) automate their <strong>BPLS</strong> and connect to the Philippine Business Registry<br />

(PBR). 6 By 2007, all 130 LGUs in Region 3 had completed streamlining reforms – three years<br />

before performance standards were officially promulgated in August 2010 (Table 3-1). Two cities<br />

even had their business registration process certified under ISO 9000.<br />

Table 3-1<br />

<strong>BPLS</strong> Implementation in Central Luzon<br />

Province<br />

No. of Cities/<br />

Municipalities<br />

Cities/Municipalities Implementing Streamlined <strong>BPLS</strong><br />

2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007-2009<br />

Aurora 8 1 2 2 8 8<br />

Bataan 12 1 1 4 12 12 12<br />

Bulacan 24 2 2 3 7 23 24<br />

N. Ecija 32 2 2 3 7 32 32<br />

Pampanga 22 1 2 3 14 22 22<br />

Tarlac 18 1 1 2 2 17 18<br />

Zambales 14 1 2 3 14 14 14<br />

TOTAL 130 8 11 20 58 127 130<br />

SOURCE: DTI, Region III. 2009 Presentation.<br />

The Region 3 initiative is a model of political resolve to make reforms and the persistence of a<br />

government agency in following the instructions of the President. Leading the project, DTI<br />

Region 3 had provincial governors champion reform, secured financial support through the<br />

foundation organized by the governors, coordinated technical support provided to LGUs from<br />

NGAs and the development community, and instituted an award system that encouraged LGUs to<br />

compete with each other in improving how mayor’s permits were issued.<br />

6 The PBR is a business registry database managed by DTI under Executive Order 587 issued on December<br />

8, 2006. It has evolved to streamline registration procedures through a web-based registry that links the<br />

databases of various agencies (i.e., the Securities and Exchange Commission, the Cooperative<br />

Development Authority, the Bureau of Internal Revenue, the Social Security System, the Home<br />

Development Mutual Fund, the Philippine Health Insurance Corporation, e-ready LGUs, and e-ready<br />

licensing agencies). While a number of LGUs have been linked to PBR since 2009, the system is being<br />

enhanced and tested.

P AST <strong>BPLS</strong> R EFORMS IN THE P HILIPPINES 23<br />

<strong>BPLS</strong> <strong>Reform</strong>s in Mindanao, 2003<br />

One of USAID’s early initiatives to promote business registration reform in Mindanao was the<br />

Transparent Accountable Governance (TAG) project. TAG was designed as an anticorruption and<br />

good governance project that adopted “increasing transparency and accountability in government<br />

transactions” as a theme (Asia Foundation 2008). The Business Permit and Licensing Study, a<br />

five-year activity under the project, initially covered 7 cities but expanded to 16. 7 Assistance<br />

focused on procedural reforms that covered steps, processing time, forms, clearances, permitting<br />

fees, signatories, personnel, and corruption. The end-of-project report covered results, city case<br />

studies, and recommendations. Sustainability in reform is always an ongoing concern with <strong>BPLS</strong><br />

reform and TAG was not directly an investment climate improvement project. However, TAG<br />

had some success in streamlining the business permitting system in the target cities and some of<br />

the beneficiary cities won awards (e.g., Koronadal).<br />

<strong>BPLS</strong> <strong>Reform</strong>s in the Visayas, 2004<br />

The GIZ spearheaded <strong>BPLS</strong> reforms in the Visayas through two projects: the Private Sector<br />

Participation (PSP) Project and the Decentralization Project (DP). While PSP helped improve the<br />

business and investment climate for micro, small, and medium enterprises, DP helped improve<br />

national and local governance. DP supported the harmonization and streamlining of processes in<br />

and between local governments and thus fostered local planning, financial management, interlocal<br />

cooperation, and capacity developments.<br />

The PSP project, with DTI, piloted <strong>BPLS</strong> reform in Bacolod (Region 6) and in Ormoc and<br />

Palompon (both in Region 8) in 2005. A third pilot region—Region 7—was selected in 2007.<br />

There, DP and PSP joined forces and selected the municipalities of Barili and Consolacion as<br />

pilots. The pilots were later replicated in various municipalities in Regions 6, 7 and 8 (see Table<br />

3-2).<br />

As in Central Luzon, GIZ assistance covered a good number of municipalities. In the absence of<br />

standards, GIZ’s approach enabled municipalities to determine areas for reform, but basically<br />

covered number of steps, amount of processing time, documentation requirements, and<br />

signatures. Manuals, toolkits, and learning modules were produced under the two projects. The<br />

good documentation of project experiences and accomplishments contributed to the design of the<br />

government’s <strong>BPLS</strong> project.<br />

<strong>Reform</strong>s in the Visayas were concentrated in small and medium size municipalities (except for<br />

Iloilo, Cebu City) as compared to those in Mindanao and Luzon. Yet the reforms led LCEs to<br />

understand that they can raise revenue by improving service delivery, particularly business<br />

permitting and licensing. In some LGUs, such as Iloilo, GIZ assistance also covered the<br />

introduction of iTax, software with a module for tracking business fees, in addition to other LGU<br />

operations like real property taxes. 8<br />

7 The 16 cities were Cotabato, Dapitan, Marawi, Iligan, General Santos, IGaCoS, Surigao, Butuan,<br />

Dipolog, Koronadal, Malaybalay, Oroquieta, Ozamiz, Panabo, Tacurong and Zamboanga.<br />

8 GIZ later developed an i<strong>BPLS</strong> to complement its <strong>BPLS</strong> reform assistance in Mindanao.

24 <strong>BPLS</strong> R EFORM P ROGRAM G UIDE<br />

Table 3-2<br />

<strong>BPLS</strong> Pilot Areas in the Visayas<br />

Region 6 Region 7 Region 8<br />

Pilots Bacolod Barili, Consolacion Ormoc, Palompon<br />

Replicators Iloilo<br />

Escalante<br />

Silay<br />

Sagay<br />

Cadiz<br />

Kabankalan<br />

Talisay<br />

San Carlos<br />

Bago<br />

Victorias<br />

Buenavista<br />

Dumangas<br />

Estancia<br />

Oton<br />

Pototan<br />

Kalibo<br />

Malay<br />

Roxas City<br />

San Jose<br />

Passi<br />

Cebu City<br />

Tanja<br />

Liloan<br />

Larena<br />

Danao<br />

Siquijor<br />

Talisay<br />

Minglanilla<br />

Naga<br />

Argao<br />

Dumaguete<br />

Bayawan<br />

Valencia<br />

Burauen<br />

Palo<br />

Isabel<br />

Naval<br />

Catbalogan City<br />

Borongan<br />

Calbayog<br />

<strong>BPLS</strong> <strong>Reform</strong>s in the <strong>National</strong> Capital Region, 2008<br />

Most early initiatives to simplify business permitting focused on municipalities and small cities.<br />

The first to involve highly urbanized cities was the IFC’s Regulatory Simplification Project<br />

(RSP), which focused on procedures for new business permits. Started in 2008, RSP extended<br />

technical assistance for reducing the time, cost, and procedures for starting a business to four<br />

cities in the NCR: Mandaluyong, Marikina, Manila, and Quezon City. Four principles<br />

characterized the project: adoption of one business application form; implementation of a onetime<br />

assessment and one-time payment, and creation of a joint inspectorate system. All four cities<br />

adopted the single registration form and one-time assessment and one-time payment schemes. As<br />

a result, the 14 steps in the standard business registration process were reduced to eight, and the<br />

processing time was reduced to one day.<br />

To complement the RSP, the IFC started the Standard Business Registration Process (SBRP)<br />

project with the League of Cities of the Philippines (LCP). The league was headed by then-Mayor<br />

Benhur Abalos, who was also chair of the Union of Local Authorities of the Philippines. A<br />

technical working group on business regulation (entry) reform was organized to advocate<br />

business regulation reform in the NCR. The project was conceived with the following outputs in<br />

mind: (1) legal and procedural review of local and national regulations, (2) standard business<br />

registration procedures, (3) issuance of department orders and local ordinances to implement<br />

standard procedures, (4) action and advocacy plans, and (5) compliance monitoring. Activities<br />

culminated in the signing of the Joint Memorandum Circular by DILG, DTI, SSS, and NCR<br />

mayors in February 2009 (see Legal Basis for <strong>BPLS</strong> <strong>Reform</strong>s). While the focus was on new

P AST <strong>BPLS</strong> R EFORMS IN THE P HILIPPINES 25<br />

business applications, the recommendations were also considered in setting the <strong>BPLS</strong> standards<br />

in the JMC 2010.<br />

Streamlining of Business Renewal Processes, 2009<br />

In 2009, the <strong>BPLS</strong> Streamlining Project was implemented nationwide as a joint undertaking of<br />

the PDF working groups on growth and investment climate and the working group on<br />

decentralization and local government, with DTI and DILG as conveners, respectively. Both<br />

working groups wanted to put into place practical measures to enhance national and local<br />

competitiveness. The focus was on reforming the business renewal processes of key cities and<br />

municipalities in highly urbanized areas where the bulk of businesses are located. In contrast to<br />

earlier <strong>BPLS</strong> initiatives that had focused on poor municipalities, this program recognized that<br />

reforms would have the greatest impact in areas with a high concentration of firms. The program<br />

also marked the first attempt to develop service standards for business renewals, which account<br />

for the majority of annual business applications. 9 On the basis of process recommendations in<br />

earlier studies of <strong>BPLS</strong>, benchmarks were set for number of steps, processing time, and the use of<br />

a single, unified form.<br />

Twenty-eight LGUs from six regions (3, 4A, 7, 10, 11, 12) were chosen to participate in four<br />

workshops in November-December 2009 to enable them to streamline their business renewal<br />

processes in time for the January 2010 renewal period. This training was the first multidonor<br />

project on <strong>BPLS</strong> (i.e., involving GIZ, IFC, USAID’s LINC-EG). Despite the short notice, a third<br />

of the LGUs reportedly implemented at least one of the four standards for processing business<br />

renewals.<br />

Development of e<strong>BPLS</strong>, 2006<br />

Separate from the projects of development partners, the <strong>National</strong> <strong>Computer</strong> <strong>Center</strong> (NCC2) with<br />

the Development Academy of the Philippines, developed e<strong>BPLS</strong> software as part of an<br />

e-governance project that included the eRPTS. The software is free to municipalities with training<br />

provided by NCC staff. NCC2 targeted municipalities under the program because cities were seen<br />

as having the financial capacity to automate their operations. The eLGU <strong>BPLS</strong> covers the full<br />

business processing cycle (i.e., application, assessment, approval, payment and release). Twentyone<br />

LGUs are fully implementing the system.<br />

In 2006, NCC2 joined with the Mayor’s Development <strong>Center</strong> (MDC)—a training arm of the<br />

League of Municipalities of the Philippines (LMP) –and the eGov project of the Canadian<br />