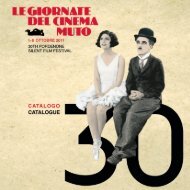

Le Giornate del Cinema Muto 2006 Sommario / Contents

Le Giornate del Cinema Muto 2006 Sommario / Contents

Le Giornate del Cinema Muto 2006 Sommario / Contents

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

prebellico, mentre il malvagio mulatto vice-governatore Silas Lynch<br />

parla con la stessa voce priva d’accento e lo stesso vocabolario<br />

espressivo dei personaggi bianchi di Dixon e di Griffith. Così il<br />

dialetto è, in una certa misura, una funzione ed un significante di<br />

classe e, in misura maggiore, un’eredità <strong>del</strong> melodramma teatrale in<br />

lingua inglese, in cui i personaggi <strong>del</strong>le classi inferiori parlano in<br />

dialetto e quelli al centro <strong>del</strong> dramma parlano un inglese privo di<br />

accenti. – DAVID MAYER<br />

Griffith, evasive about his early encounters with Louisville theatrical<br />

entertainments, claims in his unfinished autobiography that he was<br />

inspired to become a dramatist “…on seeing my first theatrical<br />

performance; it was Pete Baker who sang ‘America’s National Game’”.<br />

The date for this event is not specified, but Baker appeared in Louisville<br />

on three occasions when Griffith may have been in the audience: once at<br />

Harris’Theater in January 1894, when Baker starred in his own musical<br />

revue, Chris and <strong>Le</strong>na, and twice at Macauley’s Theatre, in September<br />

1894 as a member of Al G. Fields’ Minstrel troupe, and in September<br />

1896 when Baker had joined Primrose and West’s Minstrels. Griffith<br />

would then have been 19 or 21 years old.<br />

Pete Baker was a “burnt-cork” minstrel who,“blacked-up”, specialized in<br />

“Dutch” (i.e., German-dialect) comic material. In minstrel shows Baker<br />

was continually in blackface makeup, and he was predominantly in<br />

blackface in Chris and <strong>Le</strong>na singing comic songs and acting in comedy<br />

sketches. Griffith’s memory of Baker raises questions based on Baker’s<br />

appearance. The illustrated sheet-music cover of “America’s National<br />

Game”, written and dedicated to Pete Baker in 1889, depicted the singer<br />

in baseball togs:<br />

I am a representative of America’s National Game;<br />

The pride of all the ladies, I am well known to fame.<br />

They all do shout as I turn out,<br />

And to the plate I stride<br />

Admired by all, both great and small,<br />

I am the people’s pride …<br />

In 1889, the year of the song’s debut, an African-American ballplayer was<br />

unremarkable. By 1894, only five years later,African-Americans had been<br />

31<br />

entirely excluded from the White-only Major <strong>Le</strong>agues. Baker, appearing<br />

as a blacked-up ballplayer who claimed to be “representative” of the<br />

sport and the object of female adulation, might have seemed either an<br />

ironic figure or an anomaly, but he was neither. Griffith, who had frequent<br />

access to minstrel shows arriving for two-night engagements at<br />

Macauley’s, is likely to have ignored Baker’s blackface makeup.<br />

Blackface, originally a novelty of the 1830s, became, after the Civil War,<br />

little more than a familiar stage convention. Stage-Negro dialect was the<br />

usual indicator that minstrels were depicting low-comedy African-<br />

Americans. Burnt-cork minstrels who sang without dialect might<br />

therefore sing of their white sweethearts without transgressing American<br />

racial taboos. Similarly, blacked-up minstrels could sing in German or<br />

Irish dialect, and thus satirize other immigrant groups. The lyrics of<br />

“America’s National Game” are not in dialect, so when Baker sang it he<br />

was not performing the song in black persona. The lack of dialect<br />

bleached him white, and he could sing as the all-American sportsman the<br />

lyrics claimed him to be.<br />

Nevertheless, the fact that Griffith’s first-ever experience of American<br />

professional theatre should be a minstrel show in a Southern theatre in<br />

which many of the participants were blacked-up necessarily invites<br />

further questions about how he perceived theatrical blackness and the<br />

degree to which he found it normal practice. How, in the light of Griffith’s<br />

subsequent 11 films on the subject of the Civil War and the<br />

Reconstruction period, did stage traditions regarding racial stereotypes<br />

guide Griffith’s hand? A partial answer is to be found both in Thomas<br />

Dixon’s dialogue for The Clansman and in Griffith’s intertitles in The<br />

Birth of a Nation. In both dramas, stage-Negro dialect is attached to<br />

characters of low station, both to newly-enfranchised African-Americans<br />

(e.g., Gus) and to old retainers who cling to their antebellum<br />

subservience, whereas the villainous Mulatto Lieutenant-Governor Silas<br />

Lynch speaks with the same unaccented voice and expressive vocabulary<br />

as Dixon’s and Griffith’s White characters. Thus dialect is, to some<br />

degree, a function and signifier of class, and, to a further degree, a legacy<br />

from English-language stage melodrama, in which characters of the lower<br />

orders speak dialect and those at the drama’s centre speak unaccented<br />

English. – DAVID MAYER<br />

EVENTI MUSICALI<br />

MUSICAL EVENTS