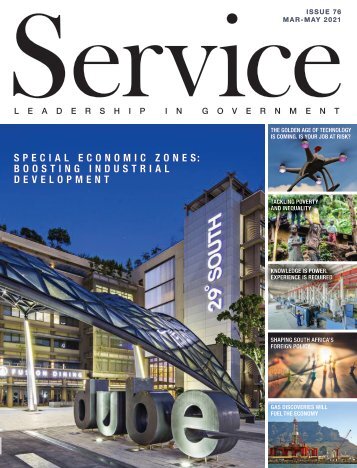

Service Magazine Issue 83

- Text

- Leadership

- Women

- Transformation

- Investment

- Service

- Political

- Government

- Environmental

- Programme

- Sector

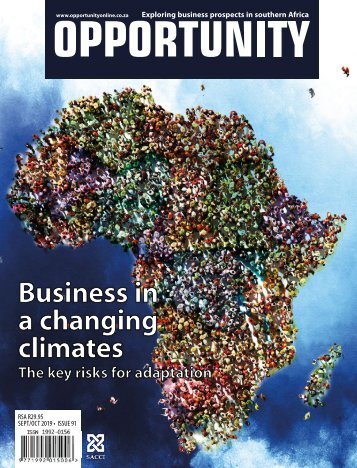

- African

- Indaba

- Infrastructure

- Economic

- Hydrogen

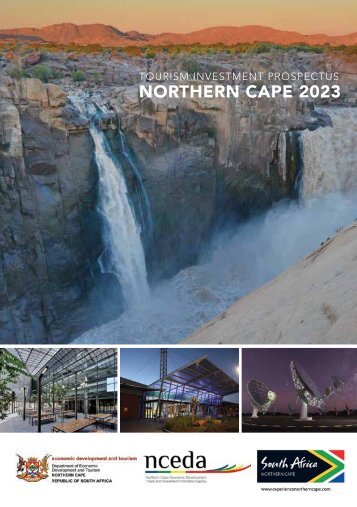

- Tourism

S energy The green

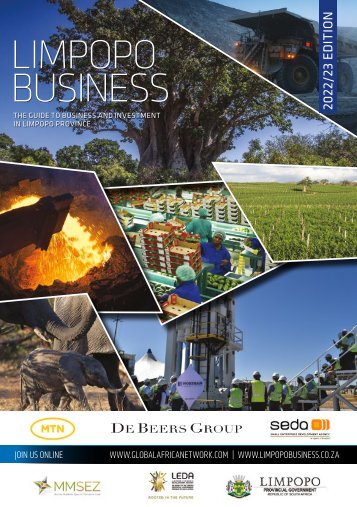

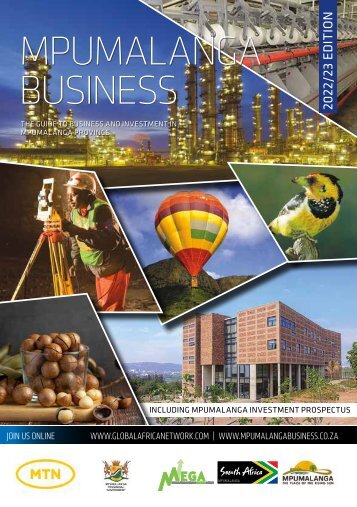

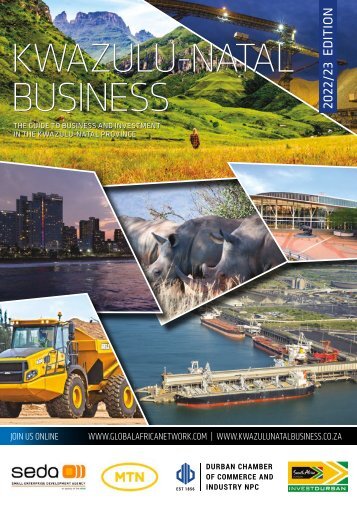

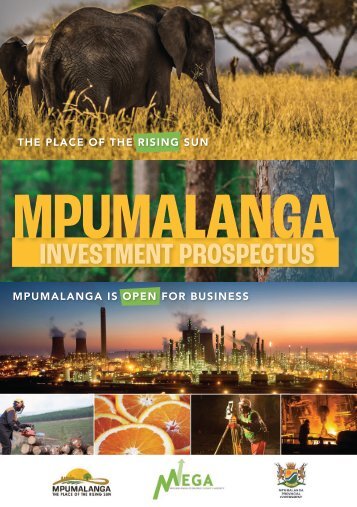

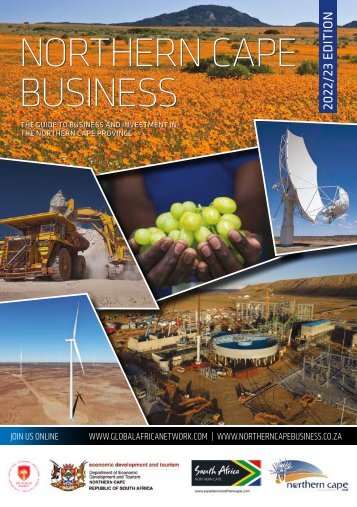

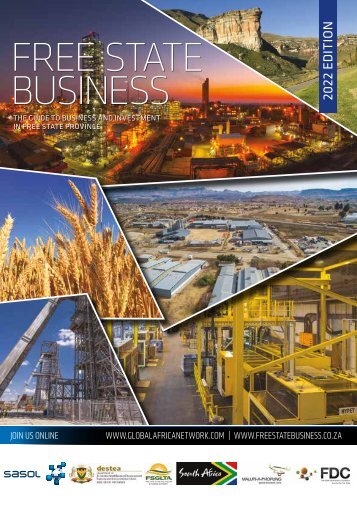

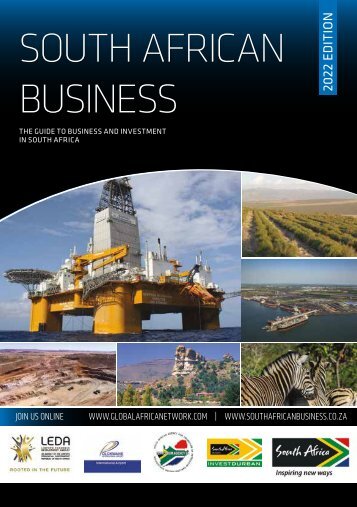

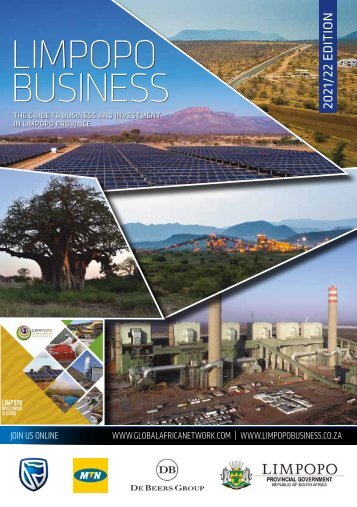

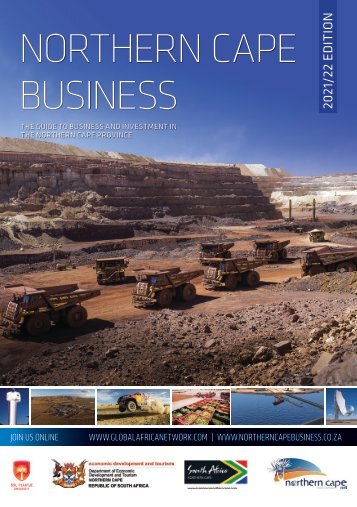

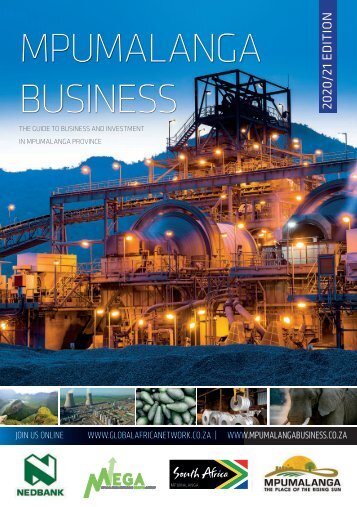

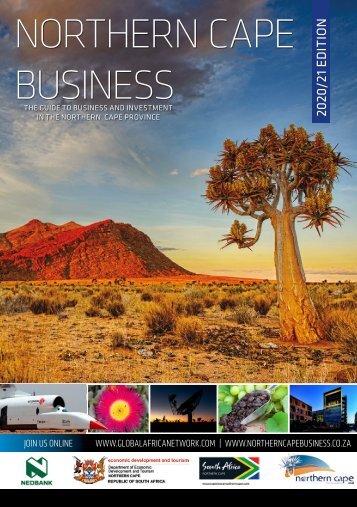

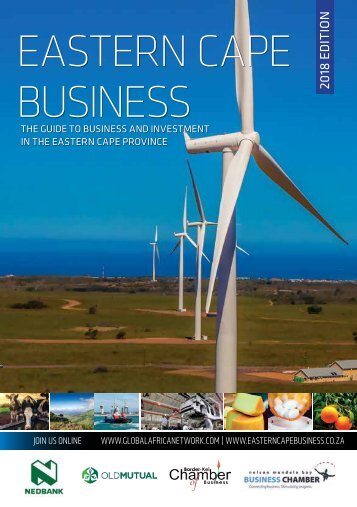

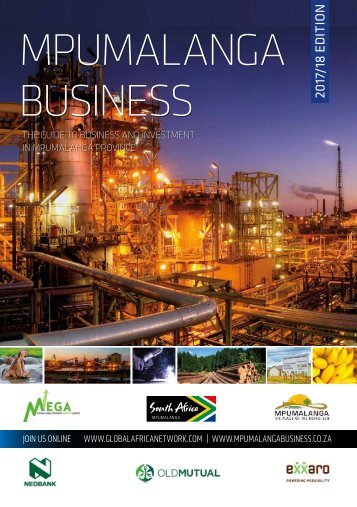

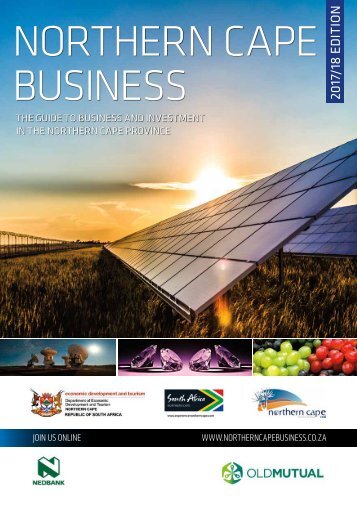

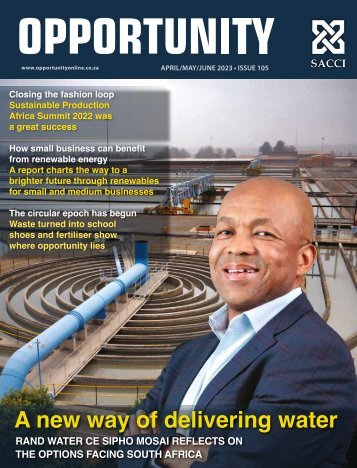

S energy The green hydrogen frontier Neocolonialism, greenwashing or just transition? T By Tobias Kalt and Makoma Lekalakala* There is much excitement around green hydrogen these days. It is often said to have great potential for combating climate change while creating jobs and economic prosperity in South Africa. Yet, there are serious risks that the development of a green hydrogen economy may follow neocolonial patterns and fall short of what is needed for a just transition. Hydrogen is a gas made from water through a process called electrolysis. This requires large amounts of energy that can come from different sources. Most hydrogen in the world is “grey” hydrogen because it is made from fossil fuels. If renewable energy is used as an energy input, this creates “green” hydrogen. It can then be converted into derivatives such as green ammonia which allows it to be shipped around the world. Governments and industrial polluters around the world have become interested in green hydrogen because of its potential to lower carbon emissions in sectors that are difficult to decarbonise through solar and wind power alone. This is the case in the steel and chemical industries. Or think of the difficulty of using electric batteries for long-distance sea or air transport. Because producing green hydrogen needs large amounts of energy, land and water, the Global North wants to meet much of its demand with imports from the Global South. With its first-class solar and wind resources, South Africa is often said to be uniquely positioned as a supplier of green hydrogen to the global market. It almost sounds too good to be true. South Africa can do all at once: export green hydrogen, combat climate change and create new jobs. Where’s the catch? GREEN ENERGY IMPERIALISM? The primary target for South Africa is the export market. Estimates are that South Africa could capture up to 10% of the global export market share. In its soon-to-be-published commercialisation strategy, the South African government prioritises the export of green hydrogen. The focus is on securing partnerships with international governments and businesses to receive foreign investments and tax revenues from exporting green hydrogen. South Africa’s flagship export project is led by Sasol in Boegoebaai in the Northern Cape. The megaproject, which is still in its feasibility 24 | Service magazine

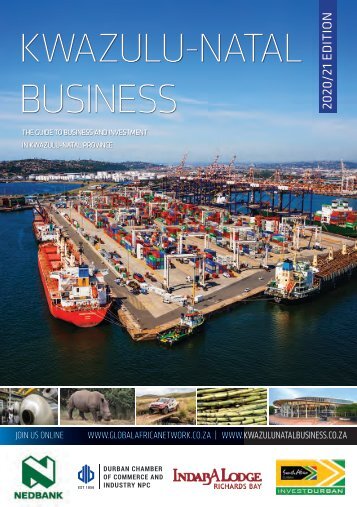

energy S Article courtesy Daily Maverick phase, aims to house 9GW of renewable energy and to expand this to 80GW by 2050 to produce green ammonia for export. This would make Boegoebaai one of the world’s largest green hydrogen projects. The key question is: will South Africa benefit from exporting green hydrogen? In a globally unequal system, benefits from the green hydrogen trade risk being captured by the Global North and the national elite in South Africa, while the majority lose out. South Africa’s international partners, most prominently Germany which is Energy democracy may be the way forward to solve the energy crisis in South Africa. intensively engaging with South Africa on green hydrogen, want to cash in twice. Once from importing green hydrogen at low prices, and a second time by selling the technology needed for producing green hydrogen to South Africa. This would allow Germany to become a green technology leader and to make sure its energyintensive industries can continue to operate as usual. German economy minister Habeck is aware that Germany’s grab for green hydrogen could become the target of criticism. One of the risks associated with the export of green hydrogen is financial. The South African government hopes to benefit financially from a revenue stream from green hydrogen exports. Yet, export projects will be in Special Economic Zones that give tax breaks to project developers, thus lowering the revenue share that the state receives. Furthermore, the government sees its role in building an enabling infrastructure, such as ports needed for shipping hydrogen around the world. Because private investors would not finance such high upfront investments in an uncertain market, the state steps in and takes on debt and market risks. Almost half of the funding requirements for green hydrogen in the government’s Just Energy Transition Investment Plan (JET-IP) is earmarked for port developments. Funding commitments have been made by international governments through the Just Energy Transition Partnership (JETP), announced at COP26. Yes, it makes sense that infrastructure for exporting green hydrogen is financed by those who will benefit from importing green hydrogen. However, 97% of JETP funding comes as loans in hard currency. Though most will be at below-market interest rates, it may nevertheless create new financial dependencies and increase South Africa’s debt burden. There are also risks that the social and environmental costs of green hydrogen megaprojects will be borne by local Service magazine | 25

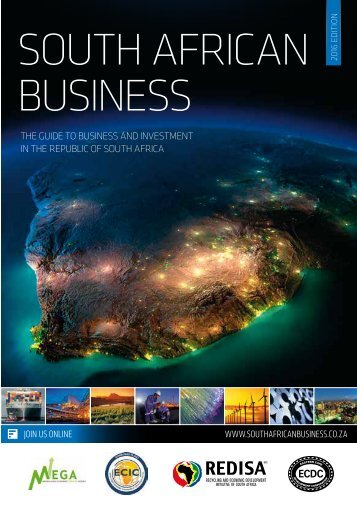

- Page 1: ISSUE 83 JUNE/JULY/AUG 2023 L E A D

- Page 4 and 5: S editor’s note We can do no more

- Page 6 and 7: S snippets SERVE AND DELIVER PUBLIC

- Page 8 and 9: S tourism Africa’s Travel Indaba

- Page 10 and 11: S tourism The tourism minister enga

- Page 12 and 13: S tourism 10 | Service magazine

- Page 14 and 15: S tourism we continue to open air r

- Page 16 and 17: S tourism Africa’s Travel Indaba

- Page 18 and 19: S local government Transforming liv

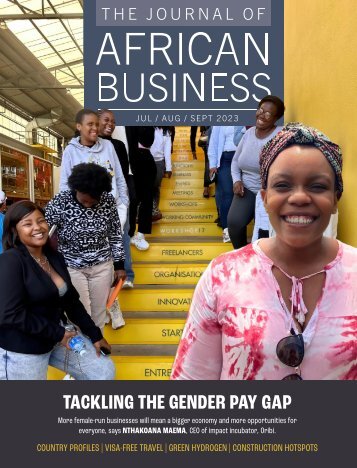

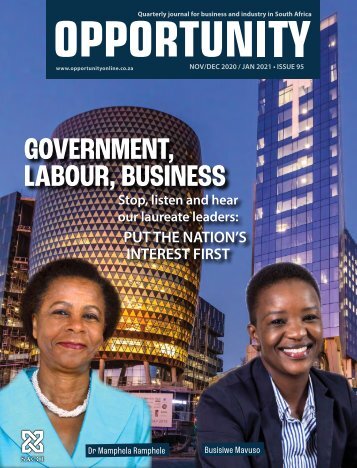

- Page 20 and 21: S women If you rise, bring someone

- Page 22 and 23: S women Women Ministers of Parliame

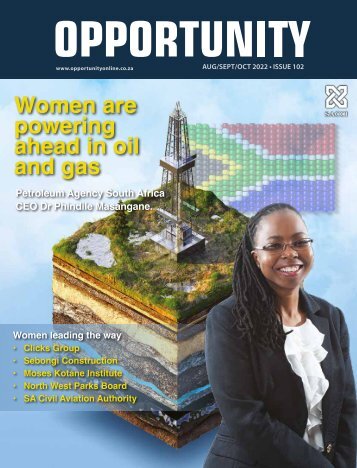

- Page 24 and 25: S oil and gas Confidence grows in o

- Page 28 and 29: S energy communities. In Boegoebaai

- Page 31 and 32: development S Partnering for a bett

- Page 33 and 34: infrastructure S • The constructi

- Page 35 and 36: infrastructure S THE FATE OF FLEETS

- Page 37 and 38: good news S The Wren Design left to

- Page 39 and 40: good news S The IDP in your Pocket

- Page 41 and 42: waste S are manufactured using recy

- Page 43 and 44: Not everything in the sea is as bea

Inappropriate

Loading...

Mail this publication

Loading...

Embed

Loading...