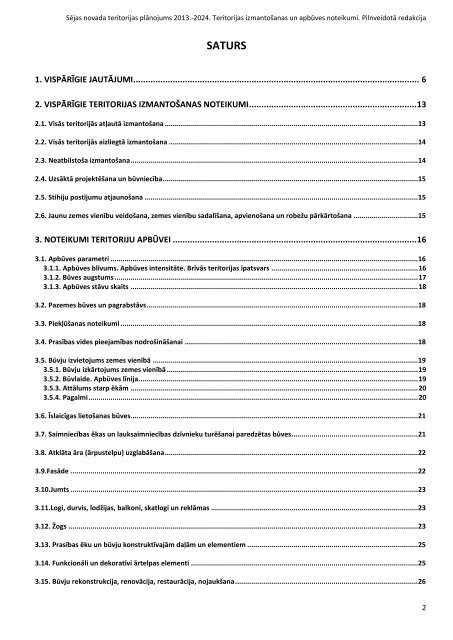

Teritorijas izmantošanas un apbūves noteikumi

Teritorijas izmantošanas un apbūves noteikumi

Teritorijas izmantošanas un apbūves noteikumi

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

menu links to find the car features. Nor does it mean that readerscan't use an aesthetic site to gain information. For example, WarGames—Catch the LandMine!! [40] is an excellent source ofinformation on the human cost of landmines, but presentsinformation in an exploratory, aesthetic way. These purposes arenot black and white but two poles on a mostly grey continuum.We surveyed 67 sites, 40 on the aesthetic side of the spectrum(self-identified as art or listed in the Electronic LiteratureDirectory [84]) and 27 on the efferent side (a site for a business ororganization, or one that sold or told something).4. SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS4.1 Summary of Anchor PropertiesThese are a few of the findings in the hypertext. Please note thatanchor properties are deeply intertwingled, and it is not one butall of the properties of the anchors on a given site that mayinfluence readers' actions and reactions.4.1.1.1 Decoration: What do they look like?The more obvious the decorations, the more prominent the anchoris in relation to the nonanchoral content. The ergodic nature ofhidden anchors point to additional interpretations of the work.Efferent sites tended to use moderate decorations, while aestheticworks used a wide range of styles.4.1.1.2 Format: What form do they take?Texts convey precise wording which allows for connotativeinterpretations and denotatively named anchors. Efferent sitestended to use textual anchors for menus while aesthetic worksmade extensive use of non-textual graphics to convey subtlermeanings.4.1.1.3 Location :Where are they?Anchors in anchor clusters (maps and menus) are viewednavigationally in relation to other anchors, while anchorsembedded in nonanchoral content are viewed contextually inrelation to the entire node. Efferent sites used mainly anchorclusters and few isolated anchors, while aesthetic use ofembedded anchors ranged from a single anchor to works entirelycomposed of anchors.4.1.1.4 F<strong>un</strong>ction: What do they do?Anchors trigger new content, form contextual bridges between theorigin and destination modes, and privilege anchoral content toprovide a semiotic overlay. Efferent sites were primarilydenotative, and aesthetic works used more connotative anchorschemes than denotative4.1.1.5 Density: How many are there?Density can be co<strong>un</strong>ted by anchors per node or by ratios. Densityconsiderations must also consider anchor clustering or isolation.Efferent sites with higher anchor densities tended to haveclustered anchors while aesthetic sites with higher densities weredivided more evenly between clustered and isolated anchors.4.1.1.6 Uniformity: How consistent are they?The more consistent the approach, the more consistent the readerinteraction and expectation. Multiple schemas can be used toperform different f<strong>un</strong>ctions (e.g., a menu for navigation andembedded text for content). Efferent sites tended to use mainlyprimary or multiple approaches while aesthetic works were moreevenly divided. No efferent site used inconsistent approaches, buttwo aesthetic works did.4.2 Overall ConclusionsReaders approach the twin tasks of interpreting and determiningwhether to trigger the anchor differently for various anchorproperty combinations. Moreover, because an anchor exists onlyas a part of a link, the anchor cannot always be discussedseparately from the link.We fo<strong>un</strong>d significant differences between sites whose primarypurpose was to provide information or sell a product and siteswhose purpose was to entertain or to engage readers in conceptualexploration. Generally, efferent sites used standard anchordecoration, had densely clustered navigation anchors rather thanembedded anchors, and used denotative rather than connotativeanchors. Aesthetic sites, on the other hand, used a broader rangeof anchor properties, showing more willingness to experiment andexplore.Merely creating an anchor is a semiotic act. Just as readersconnect a signifier with the signified, an anchor becomes asignifier for its destination. In terms of Pierce's trichotomy, theanchor serves as an index sign. On the origin node, the anchorsignals that a relationship exists and therefore emphasizes andprivileges the anchor content. This encourages readers to interpretboth the anchor and the origin node in the context of thedestination node.Semiotic f<strong>un</strong>ctions are independent of the other properties wehave identified for anchors. For example, two sites can have thesame type of anchor decoration, location, density, and <strong>un</strong>iformity,while one site uses anchors for denotative f<strong>un</strong>ctions (e.g.,Wikipedia [68]) the other site uses anchors for connotativef<strong>un</strong>ctions (e.g., the Unknown [56]).Much of the emphasis in anchor design has been on making thedestination clearer. That is, in Landow's terms, making the sitemore efficient [95]. Information-providing sites are maligned forusing highly ergodic techniques that do not guide the reader touseful information. Yet, Harpold [90] reminds us that efficiencymay not always be the goal. Instead, hypertext offers anopport<strong>un</strong>ity for an exploratory journey and anchors can also serveas a way to delay the goal and entice readers to experience moreof the text.5. ACKNOWLEDGMENTSOur grateful appreciation go to Jim Rosenberg and StuartMoulthrop for guiding us through the process. We also salute allof the Hypertext Conference Committee for grappling with theissues a hypertext paper presents.6. REFERENCESPlease see the hypertext for references.