publication for website

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

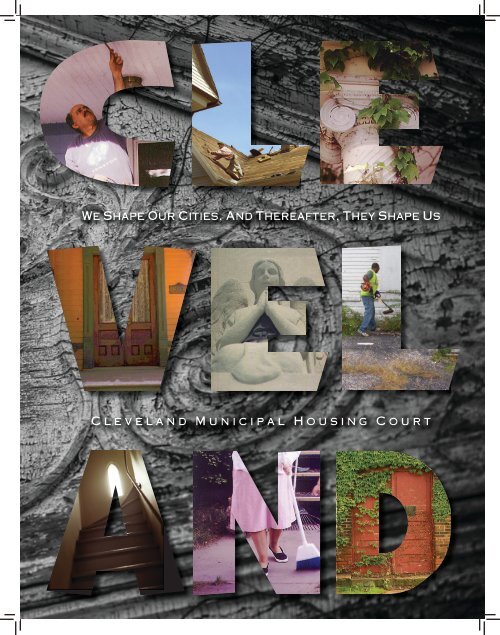

We Shape Our Cities, And Thereafter, They Shape Us<br />

C l e v e l a n d M u n i c i p a l H o u s i n g C o u r t

Acknowlegements<br />

The Housing Court wishes to<br />

acknowledge the community<br />

policymakers, legislators,<br />

attorneys, judges, and residents<br />

of the City of Cleveland whose<br />

tireless advocacy made the<br />

Housing Court a reality.<br />

The Housing Court would like to<br />

recognize, as well, its staff, past<br />

and present, whose knowledge,<br />

expertise and passion have helped<br />

Finally, thanks to the following<br />

individuals, <strong>for</strong> their assistance<br />

in telling this story of the<br />

Housing Court and its work:<br />

Benjamin Faller<br />

Gaylord Consulting<br />

Holly Hagen<br />

Ben Kotowski Design<br />

Aaron Kotowski Photography<br />

Jerome Krakowski<br />

Mary Mihaly<br />

Barbara Reitzloff<br />

Diana Twymon<br />

Heather Veljković

he Housing Court has jurisdiction over criminal cases involving violations<br />

of the City’s housing, building, fire, zoning, health, waste collection, sidewalk, agricultural<br />

and air pollution codes. The Court also hears civil cases involving landlord/tenant disputes,<br />

<strong>for</strong>eclosures, actions <strong>for</strong> nusiance abatement and receiverships.<br />

At the Cleveland Municipal Housing Court, we are committed to improving the quality of life<br />

in our neighborhoods. Through fair, tough, and compassionate adjudication and<br />

mediation the court strives to protect the health, safety and aesthetics of the properties and<br />

physical environments of our communities.

Dear Reader,<br />

The Housing Court celebrated its 35th anniversary in 2015.<br />

Court – from its inception, through its growth, to the present. In doing so, we considered, as well,<br />

at the City of Cleveland, and the social and political <strong>for</strong>ces at work during those times.<br />

Cleveland has seen its share of struggle during the past three and a half decades. We have worked<br />

to keep our communities intact, though some streets have given way to crime and disorder. As<br />

property owners have lost their jobs and homes, or simply relocated, our strong housing stock has<br />

deteriorated. Despite improvement in some neighborhoods over the past 35 years, others have<br />

unraveled be<strong>for</strong>e our very eyes.<br />

At the same time, p eople and organizations with new or renewed energy have given us hope.<br />

In the 1970s, <strong>for</strong> example, neighborhood organizers and the community development network<br />

en<strong>for</strong>cement in cases involving property owners and code violations. The Cleveland Housing<br />

Court was one of the products of this community activism.<br />

We are now in the midst of another surge of renewal in Cleveland’s neighborhoods. A building<br />

is b eginning<br />

to<br />

turn<br />

the<br />

City<br />

around.<br />

Organizations<br />

are<br />

creating<br />

partnerships,<br />

collaborating<br />

their creativity on neighborhoods and neighborhood issues, including abandoned and distressed housing.<br />

number of bank-owned properties in the City, has presented the Court with caseloads which are larger, more complicated and more challenging. The<br />

increase in property owners who live out of state, or even out of the country, has made the process of securing the attendance of criminal defendants<br />

orders. At the same time, the number of resources available to distressed owner-occupants has decreased sharply, requiring the Court’s staff to work<br />

even more creatively with homeowners to achieve compliance with City codes.<br />

The Housing Court remains committed to bringing new solutions to the City’s increasingly-complicated housing problems.<br />

Fortunately, it is not acting alone. The City is demolishing abandoned structures at an unprecedented rate.<br />

Neighborhoods host new construction, from townhomes to apartment buildings and business centers.<br />

Banks and other lenders are beginning to see the value in releasing liens to clear title, helping move<br />

new uses <strong>for</strong> old spaces. Slowly, but surely, hope is returning to<br />

Cleveland’s neighborhoods.

It has been my privilege to be the Housing Court Judge <strong>for</strong> more than half of the Court’s life. During that time, the expertise of the Court’s staff has<br />

of housing-related problems in the City of Cleveland.<br />

The Housing Court’s accomplishments have earned it a reputation <strong>for</strong> implementing the “best practices” among similar problem-solving courts. At the<br />

same time, it is clear that a great deal of work remains. While the Court has increased its educational programs, many property owners and tenants are<br />

still unin<strong>for</strong>med about their basic rights and responsibilities. The Court, through community control sanctions, has encouraged owners with multiple<br />

properties to develop comprehensive management plans <strong>for</strong> their units. But many more owners reject the Court’s advice and assistance, leading the<br />

Court to explore more avenues through which to bring these property owners into compliance with City codes and regulations. And, while an increasing<br />

Housing Court staff bring passion, dedication, knowledge and expertise to their positions. When new tools are needed <strong>for</strong> new problems,<br />

Work on the Housing Court’s second 35 years has already begun. However, as Shakespeare said, “what’s past is prologue.” So, please,<br />

where we are going. If you have thoughts or ideas about the direction of your Housing Court, I would welcome your comments.<br />

Please email me at clevelandhousingcourt@gmail.com, or call me at (216) 664-4988.<br />

Thank you <strong>for</strong> your continued support<br />

of the Cleveland Housing Court<br />

and its mission.<br />

Judge Raymond L. Pianka

“The Cleveland Housing Court is part courtroom, part emergency<br />

room that per<strong>for</strong>ms legal triage on a mix of criminal and civil<br />

cases <strong>for</strong> people who fall behind on their rent and mortgage<br />

payments — financial problems that lead to other charges,<br />

such as housing, zoning and fire code violations.”<br />

Ohio Supreme Court Chief Justice Thomas J. Moyer (1939-2010)<br />

he Years: The Emergence of an Idea<br />

The creation of the Cleveland Housing Court was not an accident. It was a lengthy, sometimes rocky<br />

saga stretching across four decades. As the <strong>for</strong>ty years preceding the creation of the Housing Court<br />

demonstrated, the need <strong>for</strong> a specialized, housing-focused court was clear. But making the Court a<br />

reality was no easy task.<br />

Housing issues began to come to the <strong>for</strong>efront in Cleveland in the 1940s. During World War II,<br />

Cleveland’s population swelled with wartime factory workers. Cleveland factories offered industrial<br />

jobs, and thousands of families migrated from Appalachia and the Deep South to take advantage of the<br />

wartime industrial production boom. But the sudden influx of families in search of wartime jobs led to<br />

scarce quality, af<strong>for</strong>dable housing. To meet the housing demand, the City’s single-family homes were<br />

parceled into apartments. This effectively was the first step in Cleveland’s path to overcrowding and,<br />

eventually, neighborhood blight.<br />

Com<strong>for</strong>table, economical housing was even scarcer after the War as servicemen returned home. “By<br />

the early 1950s, Cleveland stood at a crossroads,” wrote Dennis Keating and Norman Krumholz. 1 “Its<br />

central business district and its neighborhoods were deteriorating, crime was worsening, and thousands<br />

of city residents were leaving <strong>for</strong> new homes in the suburbs.” 2<br />

Even the U.S. Supreme Court supported ef<strong>for</strong>ts to eliminate urban blight in the nation’s cities. In<br />

Berman v. Parker, the Court upheld legislation intended to beautify and redevelop the District of<br />

5

Columbia, holding Congress could consider aesthetic as well as health<br />

concerns when enacting the legislation. 3 The Court noted:<br />

“Miserable and disreputable housing conditions<br />

may do more than spread disease and crime and<br />

immorality. They may also suffocate the spirit by<br />

reducing the people who live there to the status of<br />

cattle. They may indeed make living an insufferable<br />

burden. They may also be an ugly sore, a blight<br />

on the community which robs it of charm, which<br />

makes it a place from which men turn. The misery<br />

of housing may spoil a community as an open<br />

sewer may ruin a river.” 4<br />

Cleveland was first awakened to the housing court concept when several<br />

city councilmen attended the National Conference of Councilmen<br />

& Aldermen in Baltimore, Maryland in March 1950. 5 Baltimore’s<br />

housing court, the first in the nation, had been established in 1947. The<br />

Plain Dealer reported that the Baltimore Housing Court combined<br />

features of Cleveland’s board of appeals and municipal court, and<br />

dealt with violations of the housing, zoning and sanitary codes. 6<br />

In late April 1950, the Plain Dealer published a statement by the editor<br />

of American Builder magazine, E.G. Gavin, that cities should “clean<br />

up slums, don’t tear them down . . . and in the case of rental units—<br />

which most slum dwellings are—to make owners con<strong>for</strong>m to the<br />

law.” 7 Gavin advocated the creation of a housing court to prosecute<br />

property owners who otherwise did not comply with code violation<br />

notices. His attitude was a prelude to the spirit and process of the<br />

Cleveland Housing Court today.<br />

Clevelanders again put the spotlight on Baltimore’s housing court in<br />

1952, inviting that city’s redevelopment director, Richard Steiner, to<br />

speak to the Cleveland chapter of the American Institute of Architects<br />

(AIA). His message: if voters fully understand the benefits of<br />

redevelopment, which depends on en<strong>for</strong>cement of building codes, they<br />

will allocate money <strong>for</strong> it as they did in Baltimore. 8<br />

By 1953, Cleveland’s activist community started to advocate a housing<br />

court as a way of preserving the City’s neighborhoods. “Speak out,” Rev.<br />

Hubert N. Robinson, pastor of St. James AME Church, told the annual<br />

meeting of the Central Areas Community Council. “It is our right to have<br />

decent housing, but it is also our responsibility to get all those plans off<br />

the drawing board.” To residents of the Central neighborhood, he issued<br />

his strongest challenge: “. . . be vocal and be loud. . . .If you don’t speak<br />

out as an individual, as a citizen, as a victim of bad housing, how can you<br />

expect hopefully that someone else will?” 9<br />

Locally and nationally, momentum <strong>for</strong> redevelopment and eliminating<br />

slums was building. Housing courts often were part of the proposals.<br />

The National Association of Home Builders (NAHB) released a threepart<br />

plan in July 1953 to eliminate blight. It called <strong>for</strong> creation of a<br />

housing code to “put a floor of decency under every home,” housing<br />

inspectors to check violations, and the establishment of a housing court<br />

to ensure compliance. The plan further contemplated an aggressive<br />

public relations campaign to in<strong>for</strong>m the public. 10 The movement was<br />

bolstered in 1954, when Cleveland Municipal Judge John V. Corrigan<br />

called <strong>for</strong> a Cleveland Housing Court. The current system, he noted,<br />

was ineffective and slow, and he cited Baltimore’s success in en<strong>for</strong>cing<br />

housing, sanitary and fire codes. 11<br />

No one took action on the idea <strong>for</strong> five years. In January 1959, Cleveland<br />

Mayor Anthony J. Celebrezze, along with several suburban mayors,<br />

met with Cuyahoga County’s state legislators. They recommended<br />

establishment of a housing court as a branch of Cleveland’s alreadyexisting<br />

judicial structure. In October of that year, the City hired fifteen<br />

new housing inspectors, doubling their ranks. In an editorial, The Plain<br />

Dealer conceded there “may be a need” <strong>for</strong> a housing court: “Frankly,”

Witt and Wisdom in a Problem-Solving Court<br />

Housing Court works hard to give parties opportunities to resolve cases without trial. The Court reserves the most<br />

complicated and delicate of these cases <strong>for</strong> Alternative Dispute Resolution Specialist, C. David Witt. In the summer of 2010, Mr. Witt<br />

helped parties resolve a contentious dispute involving a Warehouse District nightclub. Residential tenants and nearby businesses<br />

complained about the large, unruly crowds attracted by the hip-hop club. The owner of the building took legal action against<br />

the owner of the club, who, backed by the NAACP, claimed that racism was behind the ef<strong>for</strong>ts to shut down his business.<br />

Three lawsuits were filed, including one in Housing Court. The landlord claimed that the club’s noise levels violated the lease.<br />

Judge Pianka directed the case to Mr. Witt <strong>for</strong> alternative dispute resolution (ADR). After multiple settlement conferences, the<br />

parties resolved the case with an agreement that encompassed noise levels, the role of bouncers and the eventual expiration<br />

of the club’s lease. Though hardly typical of the cases he handles, Mr. Witt points to it as an example of how ADR works. “We<br />

don’t settle everything, but we settle almost everything,” he says. In fact, 92 percent of 235 civil cases that went to Mr. Witt<br />

<strong>for</strong> ADR in 2014 resulted in non-trial settlements. “Ruling on a case is usually about winning and losing. At least half your parties<br />

leave disappointed. Mediation, on the other hand, is not about winning and losing. It’s about problem solving. In that sense, a<br />

successful mediation is a better resolution of a dispute, both emotionally and practically.”<br />

ADR isn’t just <strong>for</strong> the large and complex cases, however. Many<br />

eviction cases also are resolved through mediation. Gary Katz,<br />

a Housing Court Mediator, estimated that he handles 1,400 of<br />

the more than 10,000 civil cases that come be<strong>for</strong>e the court<br />

each year. In a typical resolution to an eviction case, the tenant<br />

agrees to leave, and the landlord gives the tenant more time<br />

to find other accommodations. The Judge and Magistrates<br />

can refer cases to mediation or other ADR opportunities,<br />

or the parties involved can request it at any stage. “It’s a<br />

practical thing to bring a case to an agreed resolution and<br />

know what that resolution is, rather than leave it up to a third<br />

party like a magistrate,” Witt says. “Sometimes mediation<br />

can be a cathartic experience. Finally they get to tell their<br />

story, and having told the story, they might be more amenable to<br />

reaching a settlement.”<br />

editors wrote, “we think the Municipal Court judges who now try<br />

these cases have not given enough thought to the cancer which slums<br />

and rank overcrowding have created in this city. . . The wrist-slapping<br />

business must be stopped.” 12<br />

The clarion call <strong>for</strong> a housing court continued into the 1960s. The<br />

Urban League <strong>for</strong>med a community action group in April 1961 to keep<br />

up the pressure <strong>for</strong> immediate action on unsafe housing. They asked<br />

that landlords’ and tenants’ responsibilities be posted in multi-family<br />

dwellings throughout the city, and were charged with exploring the<br />

usefulness of a housing court in Cleveland. 13<br />

In 1964, freshman councilman (and <strong>for</strong>mer housing inspector) George<br />

L. Forbes, moved City Council to request the General Assembly to<br />

establish a housing division within Cleveland Municipal Court. 14<br />

Several months later, on February 1, 1965, three councilmen<br />

consented to make the request of state legislators as part of their<br />

proposal <strong>for</strong> a new neighborhood rehabilitation program. 15 Forbes<br />

responded in April by proposing a “housing clinic” to augment the<br />

work of Cleveland Municipal Court in fighting neighborhood blight. 16<br />

The rhetoric intensified that September, when mayoral candidate Carl<br />

B. Stokes declared war on slum landlords as part of his campaign<br />

plat<strong>for</strong>m: “I would make absentee slum ownership an unprofitable<br />

business,” he declared. He added that as mayor, he would set up a<br />

housing court independent of Cleveland Municipal Court. 17 The<br />

rallying cry persisted through the remainder of the decade, with<br />

local and state candidates and officers of both political parties calling<br />

<strong>for</strong> housing re<strong>for</strong>m. Actual progress toward creation of Cleveland<br />

Housing Court did not come about, however, until well into the<br />

tumultuous 1970s.<br />

7

ocial and Political Change Bolsters<br />

the Call <strong>for</strong> a Housing Court<br />

The 1970s were a difficult decade <strong>for</strong> Cleveland. Still smarting from the legendary 1969 Cuyahoga River<br />

fire, the city lost almost one in four residents between 1970 and 1980 as homeowners, jobs, and wealth<br />

fled the city <strong>for</strong> the suburbs. As the population fell, the city’s aging housing stock suffered from decay and<br />

abandonment. Cleveland became the first major American city to enter default since the Depression.<br />

In the midst of these struggles, Cleveland experienced a heyday of community organizing. Community<br />

development corporations and grassroots community groups led the charge in creating a new generation<br />

of organizers set on combating poverty and its effects. The new federal block grant program, which gave<br />

neighborhood groups a voice in how to spend blight-fighting funds on a local level, empowered these<br />

groups in their ef<strong>for</strong>ts. The Ohio General Assembly also overhauled Ohio’s landlord and tenant laws. The<br />

Ohio Landlord-Tenant Act clarified the obligations of both landlords and tenants, expanded tenant rights,<br />

and created clearer consequences <strong>for</strong> owners of substandard rental housing. 18<br />

Community and legal advocates stepped up calls <strong>for</strong> a new approach to property-related code en<strong>for</strong>cement.<br />

For many years, ineffective processes and procedures plagued the city’s housing code en<strong>for</strong>cement program.<br />

This effectively allowed owners of blighted and unsafe properties to avoid significant penalties and fines <strong>for</strong><br />

code violations. Few code violation cases made it to court; even when charges resulted in fines, many went<br />

unpaid. In 1971, city inspectors identified over 37,000 violations, but referred only 309 <strong>for</strong> prosecution. 19<br />

Advocates were concerned that housing cases passed like hot potatoes from judge to judge, resulting in<br />

delayed resolution and inconsistent or weak penalties.<br />

9

Their concerns were valid — Cleveland’s municipal court system<br />

lacked an efficient way to adjudicate code violations cases. Violations<br />

sometimes languished <strong>for</strong> years be<strong>for</strong>e offenders were brought to<br />

court. As no separate division existed <strong>for</strong> housing cases, judges<br />

rotated through the housing docket, each spending two weeks hearing<br />

cases. Frequently, the judges, with few resources to which to refer<br />

parties, continued the cases, which then became the problem of the next<br />

session’s judge.<br />

Meager fines failed to deter offenders, and only rein<strong>for</strong>ced<br />

the inferior status of housing cases. A 1966 study found that housing fines<br />

were on average less than $15.00. 20 Not only did this process often result<br />

in delay, but it permitted serial offenders to hide in plain sight without<br />

ever facing elevated penalties. And as cases languished, the problems<br />

and the decay in Cleveland’s neighborhoods only got worse. A 1967<br />

study published by the Plan of Action <strong>for</strong> Tomorrow’s Housing (PATH)<br />

described Cleveland as in a “housing crisis,” with an “ever-widening,<br />

rotting and impoverished core, surrounded by an affluent and unconcerned<br />

. . . ring of suburbs.” 21<br />

These problems further precipitated calls <strong>for</strong> a housing court in Cleveland.<br />

By the 1970s, Baltimore’s housing court was not the only one in the<br />

nation. Specialized courts <strong>for</strong> housing had also taken root in other cities<br />

such as Pittsburgh, Boston, and New York. The campaign <strong>for</strong> a Cleveland<br />

Housing Court took on new political viability when Oberlin College<br />

student and City Councilman James Rokakis wrote a paper on the idea.<br />

Rokakis advocated <strong>for</strong> a housing court in Cleveland, and<br />

enlisted the support of State Senator Charles L. Butts, who<br />

sponsored the bill in the General Assembly to create such a<br />

court 22, and Terence Copeland to help him lead the ef<strong>for</strong>t.<br />

“Cleveland at that time was a divided city,” Copeland recalls, “and it<br />

was rare <strong>for</strong> councilmen on the east and west sides of town to partner on<br />

anything. But both sides of town had dilapidated housing,” he says. “We<br />

thought it would be good <strong>for</strong> Cleveland to have this Court to address the<br />

problem. We worked as a team, speaking at various meetings across the<br />

city talking about Housing Court. We made it our goal to let everyone<br />

know it was needed on both sides of town, and enlisted the support of<br />

about 20 neighborhood leaders and housing advocates to help us.”<br />

Despite Rokakis’s advocacy and Butts’s support, the housing court<br />

proposal was met with vocal opposition, particularly from the judiciary.<br />

The Chief Administrative Judge of the Cleveland Municipal Court, Edward<br />

F. Katalinas, opposed the bill, telling the Cleveland Plain Dealer that<br />

“[if] you put one judge on housing full time, he wouldn’t know what to do<br />

with himself…we have less than one case per day filed <strong>for</strong> the entire city<br />

of Cleveland on the housing code.” 23 Then-Governor James Rhodes also<br />

disapproved of the idea.<br />

But the chorus in favor of a housing court was louder. Almost as one voice,<br />

community groups, neighborhood activists and many lawyers, politicians<br />

and judges urged the creation of a specialized court in Cleveland to address<br />

the City’s many housing-related challenges and the growing number of<br />

housing-related disputes. 24 They recognized, even be<strong>for</strong>e its creation, that<br />

the Court would need to take a unique approach: seeking compliance,<br />

rather than simply imposing fines.<br />

On November 30, 1979, the Ohio General Assembly passed a bill authored<br />

by Harry J. Lehman of Beachwood, paving the way <strong>for</strong> the bill to become<br />

law on January 1, 1980. 25 Though advocates feared a veto, Rokakis was<br />

able to convince then-Mayor George Voinovich to persuade Rhodes to<br />

allow the bill to become law without his signature, and the housing court<br />

became a reality. 26 The Court’s creation “was viewed as both an important<br />

urban re<strong>for</strong>m and a grassroots advocacy victory,” said Robert Jaquay,<br />

associate director of the George Gund Foundation and a Housing Court<br />

prosecutor in the early 1980s. 27<br />

10

Housing Court – Justice Beyond the Four Walls of the Courtroom<br />

“The Housing Division of the Cleveland Municipal Court is now in session.” These are words you normally would hear inside<br />

Courtroom 13B at the Justice Center – the heart and home of the Housing Court. But today, these words are being spoken in the<br />

living room of a dilapidated single family home in the City’s Slavic Village area. The Housing Court Judge, his bailiff, City prosecutor<br />

and the public defenderr stand shoulder-to-shoulder with the defendants, a middle-aged couple who own and live in the house; the<br />

court reporter operates her stenographic machine seated on a kitchen chair.<br />

The hearing in this Housing Court case was held at the request of City Councilman Tony Brancatelli, whose ward includes the<br />

Slavic Village neighborhood—an area often referred to as the epicenter <strong>for</strong> the <strong>for</strong>eclosure crisis.<br />

invited us back.”<br />

violations. They also added new siding, new trim and landscaping, restoring some of the home’s previous grandeur. The Court’s<br />

ultimate goal of code compliance was reached.<br />

in hand.<br />

Beyond Evictions<br />

The Court’s problem-solving mission is priority in the civil<br />

cases that it hears. Eviction cases comprise the bulk of the<br />

Court’s civil docket. Ohio law requires that eviction cases—<br />

<strong>for</strong>mally known as <strong>for</strong>cible entry and detainer actions—move<br />

quickly through the court system. To meet this requirement<br />

and still provide a complete hearing <strong>for</strong> related claims, the<br />

Court splits these cases into two causes of action—the<br />

dealing with money damages and counterclaims. First cause<br />

hearings provide magistrates with the opportunity to refer tenants<br />

to available social service programs. The Court has established<br />

processes to connect seniors and those with disabilities to the<br />

a tenant is elderly or disabled, he or she is able to refer the<br />

and <strong>for</strong> connection to other available resources. The Court also<br />

mediation services just beyond the doors of courtroom.<br />

11

fter a Slow Start, Housing Advocates<br />

Win the Day<br />

As the official launch of Cleveland Municipal Court’s special housing division approached, controversy<br />

persisted reguarding its role, and officials squabbled over budgets, staffing and everyday matters such<br />

as office space.<br />

Still, housing advocates had won the day: Cleveland would have its Housing Court, the first in Ohio devoted<br />

to housing cases, both civil and criminal. The community started to believe that neglectful owners might be<br />

held responsible <strong>for</strong> allowing their properties to deteriorate. The Cleveland Housing Court was a busy court<br />

from the beginning: despite Judge Katalinas’s prediction, in its first year, Cleveland Housing Court saw<br />

6,452 eviction cases and 599 criminal code compliance cases. 28<br />

It was a rocky start, however. The first Housing Court judge was Joseph F. McManamon, already a Municipal<br />

Court judge. His first appearance on the Housing Court bench was delayed <strong>for</strong> two days because the new<br />

Court’s budget and offices had not been approved. Finally, on April 4, 1980, McManamon heard his first<br />

case: a complaint against a City worker who parked his garbage hauling equipment on a Tremont street at<br />

night. It was also the Housing Court’s first example of the Court’s enduring philosophy of solutions-based<br />

decisions: McManamon sentenced the worker to 10 days in jail and a $500 fine, but suspended the jail<br />

sentence and half of the fine on condition that he not park his equipment on neighborhood streets again.<br />

Housing Court’s growing pains continued, partly because the Court was underfunded. Cleveland City<br />

Council had slashed McManamon’s requested $93,000 budget to just $50,000, preventing him from<br />

13

hiring more than one Housing Specialist. The entire staff, including the<br />

in McManamon’s initial request. Those constraints alone kept Housing<br />

Court from reaching optimal effectiveness.<br />

The new Court’s future was challenged again that November when Judge<br />

McManamon was elected to the Court of Common Pleas, creating a fastrevolving<br />

door of judges on the Housing Court bench. McManamon<br />

was replaced by Judge Robert Malaga, who had just lost his own bid <strong>for</strong><br />

re-election to Probate Court.<br />

Many did not see Judge Malaga as a Housing Court supporter; however,<br />

he did honor the Court’s problem-solving approach to justice. “Those<br />

be mitigated if the work is done,” wrote a Cleveland Press reporter in<br />

April 1981. The newspaper quoted Judge Malaga as frequently telling<br />

defendants, “I’d rather have you put the money into the house than give<br />

it to the court.” 29<br />

Judge Malaga served only one year, replaced by Judge Eddie Corrigan,<br />

Local Rules, giving it a set of procedures and guidelines that set it apart<br />

from Municipal Court as a whole. It was an important step because of the<br />

specialized nature of cases heard in Housing Court.<br />

Judge Gaines also took the Court’s problem-solving philosophy to a<br />

higher level, assigning Housing Specialists to connect property ownerdefendants,<br />

often elderly and poor, with available programs to help them<br />

repair and maintain their homes. Resources, however, were few. One<br />

of the most popular programs, Cleveland Action to Support Housing<br />

(CASH), was available only to homeowners who were eligible <strong>for</strong><br />

conventional bank loans. Interest rates at that time hovered above eleven<br />

Housing Court’s early supporters remained frustrated over what they saw<br />

They set out to recruit a judge who would continue the Court’s established<br />

mission. They found their candidate in William Corrigan—a lawyer,<br />

neighborhood activist and <strong>for</strong>mer teacher and guidance counselor at<br />

Glenville High School. Corrigan had never served as a judge, but in<br />

1989, at age sixty-two, he ran <strong>for</strong> the Housing Court and defeated Carl<br />

Corrigan ushered in a decade of expansion <strong>for</strong> Cleveland Housing Court,<br />

including the creation of the Court’s Mediation Program, which still<br />

offers landlords and tenants the opportunity to settle their disputes without<br />

a hearing, free of charge.<br />

Judge Corrigan’s tenure also was brief. Clarence Gaines defeated<br />

Corrigan in the next election and began his term in January 1984—<br />

Housing Court’s fourth judge in four years. Judge Gaines was<br />

a competent jurist who continued to raise the professional standards of<br />

the Court, requesting a study to evaluate Court operations. The report<br />

found that despite the rapid turnover on the bench, the Court had met a<br />

primary mission—to resolve more housing cases than ever be<strong>for</strong>e, and at<br />

a faster rate. 30<br />

The Court’s community service program (below and at right),<br />

engages in projects in local neighborhoods that focus on quality<br />

of life issues.<br />

Court Community Services Assists Housing Court in Fighting Blight<br />

Toxic titles, absentee and unresponsive owners, as well<br />

as other complicated problems may delay resolution of some<br />

cases in Housing Court. Grass and weeds grow high, scrappers<br />

strip gutters and aluminum siding, vandals break windows,<br />

and litterers use the yard to dump trash. What was merely<br />

a vacant house—again— quickly becomes an eyesore,<br />

a burden on property values nearby and a danger<br />

to the neighborhood and its residents. As Housing<br />

cases are pending, decay through its use of Court

Corporation Docket<br />

One of the Housing Court’s ongoing challenges is compelling corporate defendants to appear in Court. Because the Court cannot<br />

issue an arrest warrant or impose jail time on a business entites, it had to act creatively, to cause those defendants to appear.<br />

the orders of reviewing courts. The Court considers this an evolving docket, since the existing laws <strong>for</strong> criminal procedure were<br />

not established with corporate defendants in mind. The end goal of this specialized docket, however, always remains the same:<br />

to require corporate defendants to appear in Court when criminal charges have been brought.<br />

After an initial failure to appear, a business entity is ordered to appear and service is sent out again the entity’s address of record,<br />

cause why it should not be held in contempt. If the entity yet again fails to appear at the show-cause hearing, the Court<br />

imposes sanctions until the entity appears and enters a plea. This practice has been successful in encouraging corporate defendants<br />

to appear in Court.<br />

One corporate defendant, a multi-national bank, routinely failed to appear on Judge Pianka’s docket, but ultimately made an<br />

address in Europe! This company, and many others like it, now appear consistently when summoned to the Corporation Docket.<br />

Community Services (CCS). Judge Pianka utilizes CCS to remove<br />

nuisances at problem properties.<br />

In addition to ordering a property maintained, if a property<br />

can assign defendants to per<strong>for</strong>m community service in lieu of<br />

trees. “We’re a real low-cost <strong>for</strong>m of labor to go out and remedy<br />

those kinds of problems,” said Paul Klodor, Executive Director<br />

of Court Community Services. Housing Court referred 60<br />

defendants in 2014, and they completed a total of 4,505 hours<br />

of community service.<br />

Not all the properties CCS services are vacant. The<br />

Housing Court has directed crews to the homes of the elderly and<br />

disabled who are unable do the repairs, and cannot<br />

af<strong>for</strong>d to hire someone. The work often draws the<br />

attention of neighbors pleased to see that the blight next door is<br />

being cleaned up. “It is a way <strong>for</strong> Housing Court to demonstrate<br />

to different communities that the Housing Court is tuned<br />

in,” says Klodor.<br />

15

oactive Court<br />

The 1990s ushered in a new era <strong>for</strong> Cleveland Housing Court with the beginning of JudgeWilliam Corrigan’s<br />

tenure as Housing Court Judge. Judge Corrigan understood the important role the Cleveland Housing Court<br />

could play in improving the quality of life in the City of Cleveland. 31 His proactive stance helped shed the<br />

malaise that marked the pre-1990 ef<strong>for</strong>ts at en<strong>for</strong>cement of the City’s Housing Code, and began to shape the<br />

Court’s reputation and policy going <strong>for</strong>ward.<br />

During Judge Corrigan’s tenure, Cleveland City Council increased the Court’s budget, as well as the number<br />

of Court personnel, perhaps in recognition of the increased role the Court was beginning to play with respect<br />

to issues of quality of life in the City of Cleveland. The significant amount of money that the Court generated<br />

on a steady basis likely also influenced Council’s willingness to increase funding <strong>for</strong> the Housing Court:<br />

during Judge Corrigan’s first two years on the bench, the Court collected a total of $310,000. The increased<br />

staffing included additional Housing Specialists, bringing their number to seven.<br />

The Housing Court possessed a deep understanding of the need to provide assistance to those under its<br />

jurisdiction. As such, the Court shouldered a responsibility to prevent and punish unsafe business practices.<br />

Such practices made life more dangerous <strong>for</strong> those who resided within the City limits. For example, during<br />

the early 1990s, the Housing Court found itself hearing cases involving heightened lead emissions that<br />

threatened surrounding neighborhoods, as well as opportunistic companies that dumped trash on City streets<br />

and vacant lots. The Court exercised its jurisdiction in cases in which it protected surrounding neighborhoods<br />

from the increased illegal dumping, 32 as well as an insufferable stench from a meat-processing operation. 33<br />

Residents of the City began to see that the Housing Court was willing to flex its muscle to provide protection<br />

<strong>for</strong> the residents whose simple goal was to enjoy their homes.<br />

17

Receivership Halts Deterioration, Restores Stability<br />

The row house on West 112th Street was quickly turning into a<br />

nightmare: The owner had moved to Cali<strong>for</strong>nia, leaving behind<br />

a roof that leaked badly. Eventually, rain and snow damaged a<br />

wall shared with neighbors. One of eight connected row houses,<br />

the property, if allowed to continue to deteriorate, could destroy<br />

other units. It would have a devastating effect on a block that<br />

had been spared the worst of the housing crisis.<br />

Neighbors turned <strong>for</strong> help to Cudell Improvement Inc., the local<br />

community development corporation. Cudell’s Executive Director,<br />

Anita R. Brindza, saw that the neighbors’ nightmare could be a<br />

dream receivership. “There are lots of reasons why community<br />

development corporations shy away from receiverships,” Brindza<br />

says. “A property might be too far gone <strong>for</strong> repairs; it might<br />

carry a too-large mortgage; it might have little resale value; the<br />

title could be tangled with liens; the housing market could be<br />

down enough to make a quick resale unlikely. But none of that<br />

would be a problem here. The brick row house could be repaired<br />

<strong>for</strong> less than its value. It didn’t carry a mortgage. Its location on<br />

a good street meant it could be resold quickly. And Cudell had<br />

enough money to pay <strong>for</strong> the renovation.”<br />

With Cudell’s help, the owners of the adjoining unit filed a<br />

receivership action in the Housing Court. The Court appointed<br />

Cudell receiver of the property, and gave them the authority to<br />

contract <strong>for</strong> and supervise the necessary repair work.<br />

Contractors fixed the roof and the common wall and cut down a<br />

large pine tree in the front yard. After repairs were completed, the<br />

three-bedroom row house was sold to a neighbor <strong>for</strong> $113,000.<br />

Cudell was reimbursed <strong>for</strong> the cost of repairs and legal services,<br />

and received a small fee, as well, <strong>for</strong> serving as receiver. The<br />

original owner eventually contacted the Court, and received the<br />

nearly $22,000 profit from the sale.<br />

“It was nice to be able to help the people who complained,<br />

because otherwise they would have had to abandon the<br />

property,” Brindza says.<br />

In recognition of his commitment<br />

and ef<strong>for</strong>ts, Housing Advocates,<br />

Inc., a Cleveland-based nonprofit<br />

public interest law firm<br />

and fair housing agency, awarded<br />

Judge Corrigan the “Housing<br />

Advocate of the Year” award, just<br />

prior to the expiration of his term<br />

as Housing Court Judge.<br />

The early 1990s also saw one of<br />

the first uses of receivership as<br />

a nuisance abatement tool. The<br />

Cleveland Restoration Society<br />

filed one of the first actions of its<br />

kind against the owner of a property<br />

on South Boulevard, ultimately<br />

saving a showcase home.<br />

One of Judge Pianka’s early initiatives was the creation of the Selective<br />

Intervention Program, or “SIP,” in 1998. SIP is a criminal diversion<br />

program designed to guide owner-occupants who are first-time offenders<br />

through the process of making repairs and bringing their properties up<br />

to City code. Each defendant in SIP is assigned a Housing Specialist,<br />

who assists the defendant in drawing up a contract with the Court,<br />

promising to complete the necessary repairs within a specific period<br />

of time. The Specialist explores resources available to the owners, and<br />

reports to the Court on the owner’s progress. At the end of the contract<br />

period, if the defendant has completed the program, the criminal case is<br />

dismissed. In 2000, just two years after the program was created, more<br />

than 300 defendants were referred into the program, with the vast majority<br />

successfully completing the necessary repairs, and avoiding the stigma<br />

of a criminal record. To date, the Court has referred more than 3,000<br />

defendants to the SIP program.<br />

The Housing Court recognized that education plays a significant role<br />

in achieving compliance with the law. In 1998, the Housing Court,<br />

In January 1996 Raymond L.<br />

Pianka took office as the sixth<br />

Cleveland Housing Court Judge.<br />

A <strong>for</strong>mer City Councilman, Judge Pianka became the longest-serving<br />

Housing Court Judge, on the bench <strong>for</strong> nineteen of the Court’s first<br />

thirty-five years. His experience as a passionate advocate <strong>for</strong> the City of<br />

Cleveland and its residents enabled him to hit the ground running. From<br />

the outset, Judge Pianka focused the Housing Court’s ef<strong>for</strong>ts on achieving<br />

compliance with the City’s codes, assisting those defendants who needed<br />

extra help, while pursuing and punishing those who attempted to elude the<br />

Court’s authority.<br />

18

collaborating with the Northeast Ohio Apartment Association, began<br />

offering quarterly presentations of “What Every Landlord Should Know.”<br />

Essentially a school <strong>for</strong> landlords, particularly those new to the business,<br />

this program provided in<strong>for</strong>mation on landlords’ rights and responsibilities.<br />

“What Every Landlord Should Know” continues to this day, now with a<br />

counterpart program — “What Every Tenant Should Know” — presented<br />

to individuals about to enter the rental market as tenants. The Court has<br />

added an additional program, as well, “Get the Lead Out,” addressing the<br />

law and practical issues raised by lead present in residential properties.<br />

From the onset of Judge Pianka’s term, it was clear that while the Court<br />

would work to empower landlords, tenants, and property owners to<br />

comply with the law, the Court would not coddle defendants who failed<br />

to appear and answer charges against them. The Court created a Warrant<br />

Capias Unit to locate recalcitrant defendants, and compel them to appear<br />

in Court. The Court hired retired police officers as part time, temporary<br />

employees, relying on their skills to locate and persuade defendants to<br />

present themselves in court, as ordered.<br />

At right, after and be<strong>for</strong>e, a condemned historic Franklin<br />

Boulevard home, renovated <strong>for</strong> owner occupancy, and<br />

becoming a neighborhood asset after years of neglect.<br />

Opposite page: Saving a magnificent century old Georgian<br />

Revival home (far left) on South Boulevard through creative<br />

use of receivership enabled financing to be obtained in<br />

the absence of an owner who could deliver clear title.<br />

The exterior of the landmark house today, middle, and<br />

the restored stair hall, bottom.<br />

Specializing in Getting the Job Done<br />

The Housing Specialist stands on the front porch and braces<br />

herself <strong>for</strong> what lies behind the front door. Judge Pianka has<br />

assigned her to assist a woman in her mid-sixties who lives in<br />

a modest house on the City’s northeast side. The City has filed<br />

both a civil suit and criminal charges against the woman, telling<br />

the Court that the home presents health and safety hazards.<br />

The woman greets the Housing Specialist at the door and<br />

reluctantly invites her in. Almost immediately, the woman begins<br />

to explain the stacks of newspapers, books, clothing, and other<br />

household items. “I’m going to go through all this ... I need these<br />

things …this stuff over here belonged to my husband…”<br />

The woman leads the Specialist further into the small, single<br />

family home she lives in alone. The walk is precarious, at times<br />

requiring the women to hold onto doorways while climbing on<br />

piles of items. The kitchen appliances are unusable, covered<br />

with boxes, papers, and other items stretching toward the<br />

ceiling. The basement is inaccessible, due to the clutter.<br />

The house smells of animal urine. It’s another day on the job<br />

<strong>for</strong> this vital group of Housing Court employees—the Housing<br />

Specialists.<br />

The Specialists do some of their work in the court itself—<br />

testifying be<strong>for</strong>e the Judge, working with criminal defendants<br />

to locate resources to make repairs, explaining court procedure<br />

to landlords and tenants. Much of their work, however, is done<br />

“in the field,” at many of the thousands of properties be<strong>for</strong>e<br />

the Court each year. Specialists may even don ventilators,<br />

safety suits and gloves and pitch in to help work crews clean<br />

up property as part of court-ordered community service.<br />

Judge Pianka has chosen this Specialist specifically to work with<br />

this homeowner. The social work background and experience<br />

of this veteran court worker will be helpful in dealing with the<br />

woman’s hoarding issue. She will visit the property another halfdozen<br />

times, supervising, coaching, cajoling to get the property<br />

cleaned out. In this case, the hard work yields a good result—<br />

the homeowner gets rid of much of the clutter, cleans the<br />

basement, and sanitizes the property. On this first visit, though,<br />

there is still much to be done. “Okay,” announces the Housing<br />

Court Specialist, “here’s what we’re going to do first…”<br />

19

ew Challenges Test the Court<br />

Two decades after its creation, the Court already had become an essential component of the City. But a new<br />

decade <strong>for</strong> the Housing Court brought new challenges. The Housing Court continued to adapt itself to meet<br />

these challenges with creative and effective solutions.<br />

At the beginning of the twenty-first century, vacant properties marred many of Cleveland’s once-vibrant<br />

neighborhoods. Estimates placed between 10,000 to as many as 25,000 vacant and abandoned properties<br />

in Cleveland. Following years of predatory lenders and often unscrupulous companies with no legitimate<br />

paperwork on properties, Cuyahoga County was also at the crossroads of another major obstacle: the<br />

<strong>for</strong>eclosure crisis, which hit Cleveland early and hard. By 2007, when the rest of the nation was just<br />

beginning to feel the effects of the housing bubble, <strong>for</strong>eclosures in Cuyahoga County surged past 14,000<br />

a year. Vandals destroyed vacant properties and stripped empty homes of plumbing, heating equipment,<br />

and recyclable materials. Homeowners whose properties were in <strong>for</strong>eclosure often were dismayed to learn<br />

that though they could not af<strong>for</strong>d their homes, they were still the legal owners of the properties, and thus<br />

responsible <strong>for</strong> their upkeep.<br />

Responding to this challenge, the National Vacant Properties Campaign and Neighborhood Progress,<br />

Inc. published Cleveland at the Crossroads. This comprehensive report urged greater cooperation among<br />

city leaders, CDCs, and the private sector to identify vacant properties and develop an en<strong>for</strong>cement and<br />

development strategy. 35 Judge Pianka recognized the need to en<strong>for</strong>ce the City Building and Housing Code,<br />

while simultaneously encouraging the partnership and creative solutions offered by the Crossroads report,<br />

in an essay he wrote <strong>for</strong> the Northeast Ohio Apartment Association. 35<br />

21

The often unscrupulous practice of property “flipping” exacerbated the<br />

<strong>for</strong>eclosure crisis in Cleveland. 37 In search of fast money, land speculators<br />

descended upon Cleveland, purchased condemned properties, and resold<br />

them at substantial markups—often without ever seeing the property, or<br />

making any improvements. These investors wanted to resell the houses<br />

quickly at a profit; compliance was not part of their plan. Mortgage<br />

companies—many out of state, and many willing to provide loans with<br />

little or no documentation—helped facilitate the scheme of property<br />

flippers. 38<br />

Notorious among these investors was Raymond Delacruz. According to an<br />

August 28, 2000 article in the Plain Dealer, “records show[ed] that Delacruz<br />

and his associates . . . bought and resold at least 50 properties, enjoying a<br />

return on their purchase investment of roughly 85 percent, while holding<br />

onto the properties an average of just four months each.” 39 In one example,<br />

Delacruz, through his associate, purchased a property on Kolar Avenue <strong>for</strong><br />

just over $20,000. However, the deed Delacruz recorded, along with an<br />

accompanying affidavit, falsely stated the associate paid $75,000 <strong>for</strong> the<br />

property. 40 Seven months later, Delacruz sold the Kolar Avenue property<br />

<strong>for</strong> $87,000. 41 Delacruz was later cited <strong>for</strong> myriad housing violations at<br />

the property. When Delacruz failed to bring the property up to code, Judge<br />

Pianka sentenced him to thirty days of house arrest in the property, so that<br />

Delacruz could properly “focus [his] energies” on the property. 42 Delacruz<br />

subsequently was convicted of federal mortgage and real estate fraud <strong>for</strong><br />

his operations throughout Cleveland and Columbus. 43<br />

The City had a difficult time en<strong>for</strong>cing local codes with respect<br />

to “property flipping” <strong>for</strong> various reasons. First, Cleveland has no law<br />

requiring home inspections at the point of sale. Second,although the<br />

City passed an “anti-flipping” ordinance in 2003, 44 the Ohio Supreme<br />

Court later held the ordinance was preempted under the Ohio Constitution<br />

by powers reserved to the State. 45 Third, though the City had previously<br />

passed a Certificate of Disclosure ordinance, prosecutors had rarely used it. 46<br />

That particular ordinance requires a seller of any one, two, three, or four-<br />

58<br />

The “Clean Hands” Docket<br />

“Good morning, ladies and gentlemen. You are here today<br />

because one or more parties to your case have outstanding<br />

criminal warrants and/or fines with the Cleveland Housing<br />

Court. Judge Pianka requires you to clear up these outstanding<br />

issues be<strong>for</strong>e allowing you to proceed in your eviction case.”<br />

This is the opening announcement to attendees of the Housing<br />

Court’s Eviction-Warrant Docket. In 2008, Judge Pianka noticed<br />

he was signing entries granting writs of restitution <strong>for</strong> evictions,<br />

while signing judgment entries to issue warrants <strong>for</strong> the same<br />

parties on his criminal docket. There is a longstanding legal<br />

principle that “he who seeks equity must do equity, and that<br />

he must come into Court with clean hands.” Christman v.<br />

Christman (1960), 171 Ohio St. 152. The Eviction-Warrant<br />

Docket was created to further prevent this practice, as well<br />

as to clear up outstanding cases pending in the Court.<br />

22<br />

In one case, a corporate Landlord cleared up outstanding<br />

warrants and fines that were preventing it from moving<br />

<strong>for</strong>ward on its eviction case, be<strong>for</strong>e the Eviction-Warrant Docket<br />

hearing; the Court there<strong>for</strong>e allowed it to proceed. However, the<br />

Tenant also appeared that day, and agreed to vacate the premises.<br />

The parties were able to reach an agreement through the<br />

Court’s Mediation Program. The Court considers this a win-winwin<br />

scenario: the Landlord received the remedy it sought; the<br />

Tenant’s goal of a “soft landing” was met; and the Court resolved<br />

its outstanding warrants and fines.<br />

Over 830 cases have been referred to the Court’s “Clean Hands”<br />

Docket since it began in 2008. As a result, hundreds of warrants<br />

and capiases have been cleared up and thousands of dollars in<br />

unpaid fines have been collected as a result of referral to this<br />

specialized docket.

unit dwelling to furnish a Certificate of Disclosure to the purchaser,<br />

outlining the condition of the property. A violation of the ordinance is<br />

a first degree misdemeanor, punishable by up to six months in jail and a<br />

$1,000 fine <strong>for</strong> an individual, and $5,000 <strong>for</strong> a corporation. 47<br />

Frustrated with the number of vacant properties ravaged by the <strong>for</strong>eclosure<br />

crisis, Judge Pianka instituted tough measures against the properties’ new<br />

owners: the lenders and investors themselves. In response to business<br />

entities, including banks and other lenders, ignoring Court summons <strong>for</strong><br />

code violations, Judge Pianka began holding hearings in the corporation’s<br />

absence, and converted these fines to cival judgment, upon which the<br />

clerk’s collection attorneys recorded liens in Cuyahoga County. By 2008,<br />

he had tried twelve companies in absentia, “leaving each unable to sell any<br />

properties in the area until it [paid] up.” 49 Judge Pianka also created the<br />

Eviction Warrant Docket, commonly known as the Clean Hands docket,<br />

preventing landlords with outstanding warrants and unpaid criminal fines<br />

from prosecuting eviction actions until the landlords appeared at and<br />

participated in their own criminal cases. The Judge’s tactics got attention:<br />

fewer property owners ignored the Court’s summonses.<br />

Toepfer provided the painted boards often are located near tidy, occupied<br />

homes, or near retail stores or other businesses, whose owners cannot<br />

escape the adjacent blight. As Judge Pianka remarked, “I think it’s making<br />

the most of a bad situation... It’s not a solution to the vacant, abandoned<br />

property crisis, but it’s one thing that can be done.” 51<br />

Throughout the 2000s, the Court also saw an increase in the number of<br />

nuisance abatement cases seeking the appointment of a receiver. These<br />

highly specialized, somewhat cumbersome cases, brought under Ohio<br />

Revised Code 3767.41, are limited to instances where a property owner<br />

has failed to remedy a nuisance property. The City, a neighbor within 500<br />

feet, a tenant, or local non-profit organization can bring the case, and have<br />

the Court appoint a receiver to make the necessary repairs to the premises<br />

to eliminate the nuisance.<br />

Judge Pianka also employed creative measures to address the City’s vacant<br />

properties. In partnership with community groups, Judge Pianka arranged<br />

with Chicago-based Chris Toepfer to paint the plywood boards, used to<br />

secure vacant houses, with scenes of people, window boxes and curtains.<br />

Toepfer’s technique, known as “artistic boarding,” attempts to make<br />

vacant properties more aesthetically attractive, and, more importantly, less<br />

likely to be targets of vandalism and other crimes. 50 The homes <strong>for</strong> which<br />

Staff confer in Court’s 13th floor Justice Center reception area,<br />

left, and in a courtroom as court is about to begin, right.

evitalization and Resilience<br />

As the first decade of the new millennium drew to a close, Cleveland residents looked at their community<br />

with optimism, blended with some harsh realities.<br />

Cleveland has continued to struggle with the results of the mortgage lending and <strong>for</strong>eclosure crises. As<br />

Judge Pianka told a reporter from Suites magazine in late 2009, “[i]f the [mortgage] crisis ended tomorrow,<br />

we’d be dealing with the fallout <strong>for</strong> another five to ten years.” 52 At that time, it was estimated that Cleveland<br />

had more than 10,000 vacant homes; since then, that number has risen to more than 15,000. 53 In 2009,<br />

economists and Washington, D.C. officially declared the recession 2007 “over”. But homeowners in<br />

Cleveland continued to feel the effects of stagnant wages and job losses, combined with increased prices <strong>for</strong><br />

labor and materials to per<strong>for</strong>m routine maintenance on their homes. As a result, many homeowners could<br />

not af<strong>for</strong>d to maintain their homes in good condition, and structures deteriorated throughout the City.<br />

The increased number of criminal case since 2009 reflects both the decline in the condition of the housing<br />

stock and the City’s stepped-up en<strong>for</strong>cement ef<strong>for</strong>ts. Between 2009 and 2012, the City filed 26,852 criminal<br />

cases. 54 The Clerk of Court, in 2012 alone, collected more than $500,000 in fines and court costs levied by<br />

the Housing Court.<br />

The Court also has seen an increased number of civil filings in recent years. On average, over 11,000<br />

civil cases are filed in the Housing Division. Most of these cases were eviction actions, the overwhelming<br />

majority <strong>for</strong> non-payment of rent. 55<br />

Still, there are signs of hope and increasing energy.<br />

25

A small portion of the civil cases filed were nuisance abatement actions,<br />

brought by neighborhood Community Development Corporations<br />

(CDCs). In these actions, CDCs sought an order from the Housing Court<br />

to declare a property a public nuisance and appoint a receiver, when<br />

necessary, after interested parties failed to make the necessary repairs.<br />

The neighborhood groups’ ef<strong>for</strong>ts moved toward abating the nuisance<br />

posed by vacant, abandoned, and poorly maintained properties one at a<br />

time. Receivership can be a costly remedy, and not every neighborhood<br />

CDC has the available cash or credit to rehabilitate property <strong>for</strong> later<br />

sale. Still, <strong>for</strong> neighbors of the handful of properties about which these<br />

actions are filed each year, the effect is dramatic—sometimes demolition,<br />

but other times complete rehabilitation, with a subsequent sale to owneroccupants.<br />

Not only is the nuisance abated, but the City often acquires<br />

new residents as well. While the City itself has the legal authority to bring<br />

these actions, it has not yet embraced this legal strategy, and has not filed<br />

any receivership actions.<br />

The City of Cleveland has taken initiative on another front. In June 2009,<br />

the City published a report on its newly-<strong>for</strong>med Code En<strong>for</strong>cement<br />

Partnership. 56 Beginning as a pilot project between the City and the<br />

Midwest Housing Partnership, the Code En<strong>for</strong>cement Partnership<br />

<strong>for</strong>malized the relationship between the City and the CDCs.<br />

The Sylvia Apartments are a perfect example of collaborative<br />

neighborhood revitalization. The Sylvia was built on Franklin Boulevard<br />

in the 1920s – part of a stretch of once-grand homes on the City’s West<br />

Side. By the late 2000s, however, the Sylvia was owned by a company<br />

that permitted it to fall into serious disrepair. In November 2008, the<br />

owner of the company died. On the brink of the oncoming winter, the<br />

tenants faced utility terminations. When no one from the owner’s family<br />

or the company came <strong>for</strong>ward to take responsibility <strong>for</strong> the building, the<br />

Detroit Shoreway Community Development Organization stepped in, and<br />

filed a receivership action in the Housing Court. 57<br />

Through the action they filed, Detroit Shoreway negotiated and secured<br />

cooperation from the City, neighborhood groups and financiers to<br />

save the three-story, 18-unit brick structure from demolition. After a<br />

$3 million renovation, in May 2012, the Sylvia was re-opened in a ribboncutting<br />

ceremony. Among those present was Mayor Frank Jackson, who<br />

remarked that the Sylvia was now the “jewel” of Franklin Boulevard. 58<br />

Also in attendance was 82 year old Eleanor French, who had called the<br />

Sylvia her home <strong>for</strong> nearly 65 years. Forced to vacate in 2008, when the<br />

building was at its worst, Ms. French happily returned to the Sylvia to see<br />

the trans<strong>for</strong>mation. 59<br />

A local television station at the Sylvia ribbon-cutting interviewed<br />

Cuyahoga County Land Bank Chief Operating Officer Bill Whitney.<br />

Whitney commented on the difficulty of structuring complex development<br />

projects: “These projects aren’t easy.” He went on to note, “[t]he structuring<br />

of these kinds of development models is really what has propelled Cleveland<br />

and its neighborhood groups to the <strong>for</strong>efront of city redevelopment…<br />

26<br />

The goal of the partnership from the outset was to make use of the<br />

in<strong>for</strong>mation the CDCs acquired about local neighborhoods in a<br />

streamlined and efficient manner. The CDCs maintain an inventory<br />

of abandoned properties, prioritize properties needing attention, and<br />

convey that in<strong>for</strong>mation to a centralized complaint system in the City’s<br />

Department of Building and Housing. The complaint department then<br />

prioritizes the incoming complaints from all sources, to make the most<br />

efficient use of staff time.<br />

The Partnership is still developing, and the City likely has not yet felt its<br />

full effect. It does illustrate, however, the undeniable need <strong>for</strong> community<br />

involvement to address the issue of declining neighborhoods. In areas<br />

where the residents and CDCs are active, neighborhoods have steadily<br />

improved. But no one individual, group, or government entity can bear<br />

the burden on its own—it takes a combined, concerted ef<strong>for</strong>t to push back<br />

the <strong>for</strong>ces of decay.<br />

It’s not just brick and mortar… It’s the heart of the neighborhood and<br />

all the people who live there.” 60<br />

And the heart of many of Cleveland neighborhoods continues to beat<br />

strongly:<br />

In the Larchmere neighborhood, the annual Larchmere PorchFest is a free,<br />

one day music festival that attracts thousands of people to hear musicians<br />

per<strong>for</strong>m on the porches of beautiful, well-maintained homes. Since its

first year, 2008, this family-friendly event has grown to feature thirty<br />

musical groups per<strong>for</strong>ming at thirty different homes throughout the day. 61<br />

The Kinsman area has welcomed CornUcopia Place, a<br />

community facility featuring a harvest preparation station <strong>for</strong> local<br />

market gardeners, and a community kitchen, where cooking and nutrition<br />

demonstrations are held. The affiliated Bridgeport Café serves handcrafted<br />

soups and sandwiches, and sells fresh, locally-grown produce. 62<br />

In Hough, neighborhood resident and activist Mansfield Frazier proposed<br />

the creation of a vineyard on a lot once occupied by a dilapidated apartment<br />

building. The vineyard, Chateau Hough, released its first bottle of wine in<br />

2014, and received 2nd place at the Great Geauga County Fair. Since its<br />

inception, the project has expanded to include the creation of a bio-cellar,<br />

a passive solar greenhouse derived from the foundation remnant of an<br />

abandoned building. 63<br />

Stockyard-Clark-Fulton has witnessed the introduction of “mow goats”<br />

to the area, an innovative approach to clearing brush from vacant lots. A<br />

team of four goats came from a farm in Madison, Ohio, to Cleveland’s<br />

near West Side, to test the use of goats to clear lots to mow-able height. 64<br />

The Cleveland Flea—a pop-up neighborhood flea market – is “part<br />

urban treasure hunt, part culinary adventure, part maker center.” This<br />

monthly flea market offers locally made jewelry, art, crafts, clothing,<br />

and food, along with artist demonstrations in the St. Clair-Superior<br />

neighborhood. 65<br />

The Detroit Shoreway neighborhood celebrated the renovation of the<br />

historic Capitol Theater. Situated in the heart of the Gordon Square<br />

Arts District, the Capitol Theater is now locally owned and operated<br />

by Cleveland Cinemas. During its 2012-2013 season, the Cleveland<br />

Orchestra launched its “At Home” neighborhood residency program in<br />

Gordon Square, with per<strong>for</strong>mances at the Capitol Theater. 66<br />

In the Lee-Harvard, Miles, and Mt. Pleasant neighborhoods, concerned<br />

residents have worked alongside Empowering and Strengthening Ohio’s<br />

People (ESOP), and the Concerned Citizens of Mt. Pleasant to re-claim<br />

their community from the ravages of crime and <strong>for</strong>eclosures. Their ef<strong>for</strong>ts<br />

have included tips that led to the raid of a suspected drug house. 67 In 2011,<br />

the Concerned Citizens, along with ESOP, confronted two property owners<br />

who owned run-down properties in the Mt. Pleasant neighborhood: first at<br />

a community meeting, then at an<br />

unannounced visit to the owners’<br />

Cleveland Heights residence. 68<br />

Concerned Citizens and ESOP’s<br />

pressure led to the property<br />

owners paying their outstanding<br />

Housing Court fines. 69<br />

Old Brooklyn is proud of its<br />

green spaces, including the Ben<br />

Franklin Community Gardens,<br />

and the Treadway Creek Trail<br />

and Greenway, a 21-acre park<br />

that links the neighborhood to the Ohio and Erie National Heritage<br />

Canalway Towpath Trail. 70 It annually participates in River Sweep,<br />

touted as “Ohio’s largest done-in-a-day cleanup ef<strong>for</strong>t.” 71 and hosts many<br />

community street festivals and events, such as Pedal <strong>for</strong> Prizes, Old<br />

Brooklyn Wings & Things Cookoff, and Pop Up Pearl. 72<br />

In the West Park area, the Hooley on Kamm’s Corners is the neighborhood’s<br />

annual street festival. The festival features live entertainment, food, and<br />

Celtic music. 73 Neighborhood residents are also working to purchase<br />

the <strong>for</strong>mer St. Mark’s Episcopal Church from the Episcopal Diocese of<br />

Cleveland. 74<br />

Along Waterloo Road in North Collinwood, anchor businesses such as the<br />

Beachland Ballroom and Tavern have helped trans<strong>for</strong>m that neighborhood<br />

into a haven <strong>for</strong> music, art, and entertainment. Every summer <strong>for</strong> over<br />

ten years, the neighborhood has also celebrated the Waterloo Arts<br />

Fest, a street-wide festival along the aptly-named Waterloo Arts and<br />

Entertainment District. 75<br />

A Housing Specialist confers with an attorney and client in court,<br />

far left. A Magistrate examines evidence during a hearing, middle<br />

left. Court Watch members attend a session of Housing Court to<br />

track a defendant’s sentence and to remind Prosecutors and the<br />

Court of the importance of the case to the community. Top, this<br />

page: A porch pillar in a historic district; one of many wellmaintained<br />

homes in Cleveland neighborhoods, too often<br />

overlooked by pundits; and a home owner paints his front porch.<br />

27

Cleveland Public Theater, left, has been<br />

a pivitol part of the public-private<br />

partnership that created the Gordon<br />

Square Arts District. A stome angel<br />

adorning the landmark St. Coleman<br />

Church. Cleveland’s places of worship<br />

help to stabilize neighborhoods.<br />

And Slavic Village, the neighborhood<br />

often referred to as the “epicenter of the<br />

<strong>for</strong>eclosure crisis,” takes pride in promoting<br />

healthy, active living. A participant in the<br />

Active Living by Design program of the<br />

Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, Slavic Village focuses on family<br />

health, from the Morgana Run Trail, a two-mile bicycling and walking<br />

path, that serves as the site of an annual Pierogi Dash 5K Run and<br />

Fun Walk, to the Velodrome, a 166-meter steel and wood Olympicstyle<br />

cycling track, installed on a patch of vacant land where a hospital<br />

once stood. 76<br />

The longevity of each of these ideas, of course, is unknown. But<br />

more important than their duration, these innovations represent the<br />

commitment of residents of Cleveland’s neighborhoods to the reinvention<br />

of Cleveland itself.<br />

Cleveland’s neighborhoods are getting a hand from some larger partners, as<br />

well. For example, the Cuyahoga County Land Reutilization Corporation,<br />

known as the County Land Bank, is a non-profit organization that<br />

strategically assesses abandoned or otherwise distressed properties, and<br />

renovates or demolishes them. The Land Bank, which has accepted dozens<br />

of property donations from Housing Court defendants, puts properties<br />

into the hands of beneficial owners, returning them to productive use, and<br />

keeps them out of the hands of real estate speculators. The Land Bank’s<br />

work clears the way <strong>for</strong> new, positive ownership of the properties. Since its<br />

inception in 2009, the Land Bank has made a difference on dozens of streets<br />

throughout Cuyahoga County, helping neighbors in those communities take<br />

pride in their homes, businesses and surroundings again. The actions of the<br />

Land Bank and other large organizations within the City can supplement<br />

and complement the work of the smaller, grass roots organizations, to<br />

revitalize our City.<br />

Evolution of the Housing Court<br />

1970’s<br />

1980’s 1990’s<br />

Late 1970s City officials, state legislators and<br />

community activists lobby <strong>for</strong> the creation of a<br />

court to handle housing issues on the Cleveland<br />

Municipal Court docket.<br />

1980 Governor James A. Rhodes allows bill to become<br />

law without his signature. The Court has five staff,<br />

including Judge Joseph F. McManamon, who was<br />

appointed by the legislature, and a Housing Specialist<br />

and a bailiff. Judge McManamon wins election to<br />

Cuyahoga County Common Pleas Court after serving<br />

10 months as Housing Court Judge.<br />

1987 Cleveland State<br />

University Professor<br />

W. Dennis Keating<br />

prepares study: “An<br />

1996 Judge Raymond L. Pianka takes office as the sixth<br />

Housing Court judge.<br />

1996 The Court creates the Warrant/Capias Unit, which<br />

Evaluation of the tracks down criminal defendants who fail to appear in<br />

1981 Governor Rhodes appoints Judge Robert<br />

Malaga <strong>for</strong> a 1-year term. More than 920 code<br />

Cleveland<br />

Court.”<br />

Housing Court. The Court establishes the Amicus Curiae volunteer<br />

program.<br />

. . . .<br />

en<strong>for</strong>cement<br />

. .<br />

cases<br />

.<br />

are filed<br />

.<br />

in the Court’s<br />

.<br />

first<br />

.<br />

full<br />

. . . . . . . . . .<br />

year of operation.<br />

1990 Judge William F. Corrigan takes office<br />

as the fifth Housing Court judge.<br />

28<br />

1979 The Ohio General<br />

Assembly passes legislation<br />

creating the Housing Division<br />

of Cleveland<br />

Municipal Court.<br />

1984 Judge Clarence Gaines<br />

takes office, becoming the<br />

fourth Housing Court judge<br />

in four years.<br />

1982 Judge Eddie Corrigan<br />

takes office as Housing Court<br />

judge. The Court creates its<br />

first set of Local Rules.<br />

1986 The Union Miles<br />

Development Corp. spearheads<br />

<strong>for</strong>mation of the Cleveland<br />

Housing Receivership Project,<br />

comprised of neighborhood<br />

groups that want to use<br />

receivership as a tool to fight<br />

abandoned houses.<br />

1992 Housing Court<br />

establishes its Civil<br />

Mediation Program.<br />

1993 The City of Cleveland<br />

Department of Community<br />

Development publishes its<br />

Building & Housing Task<br />

Force Report, recommending<br />

an expansion of code<br />

en<strong>for</strong>cement ef<strong>for</strong>ts.<br />

1993 A historic South Boulevard home is condemned<br />

and slated <strong>for</strong> demolition. The Cleveland Restoration<br />

Society files a nuisance abatement case with Housing<br />

Court, is appointed receiver, eventually restoring the<br />

grand old home.

2000’s<br />

2010’s<br />