Revista Veterinaria Zacatecas 2007 - Universidad Autónoma de ...

Revista Veterinaria Zacatecas 2007 - Universidad Autónoma de ...

Revista Veterinaria Zacatecas 2007 - Universidad Autónoma de ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Lic Alfredo Femat Bañuelos<br />

Rector <strong>de</strong> la <strong>Universidad</strong> Autónoma <strong>de</strong> <strong>Zacatecas</strong><br />

M C Francisco Javier Domínguez Garay<br />

Secretario General<br />

Ph D Héctor René Vega Carrillo<br />

Secretario Académico<br />

C P Emilio Morales Vera<br />

Secretario Administrativo<br />

M en C Jesús Octavio Enríquez Rivera<br />

Director <strong>de</strong> la Unidad Académica <strong>de</strong> Medicina <strong>Veterinaria</strong> y Zootecnia<br />

M V Z Juan Manuel Ramos Bugarin<br />

Responsable <strong>de</strong>l Programa <strong>de</strong> Licenciatura<br />

Ph D José Manuel Silva Ramos<br />

Responsable <strong>de</strong>l Programa <strong>de</strong> Doctorado<br />

Dr en C Francisco Javier Escobar Medina<br />

Responsable <strong>de</strong>l Programa <strong>de</strong> Maestría y Editor <strong>de</strong> la <strong>Revista</strong> <strong>Veterinaria</strong> <strong>Zacatecas</strong><br />

Dr en C Rómulo Bañuelos Valenzuela<br />

Coordinador <strong>de</strong> Investigación<br />

M en C J Jesús Gabriel Ortiz López<br />

Secretario Administrativo<br />

M en C Francisco Flores Sandoval<br />

Director <strong>de</strong> la <strong>Revista</strong> <strong>Veterinaria</strong> <strong>Zacatecas</strong>

Comité Editorial<br />

Aréchiga Flores, Carlos Fernando PhD<br />

Bañuelos Valenzuela, Rómulo Dr en C<br />

De la Colina Flores, Fe<strong>de</strong>rico M en C<br />

Echavarria Chairez, Francisco Guadalupe Ph D<br />

Gallegos Sánchez, Jaime Dr<br />

Grajales Lombana, Henry Dr en C<br />

Góngora Orjuela, Agustín Dr en C<br />

Meza Herrera, César PhD<br />

Ocampo Barragán, Ana María M en C<br />

Pescador Salas, Nazario Ph D<br />

Rodríguez Frausto, Heriberto M en C<br />

Rodríguez Tenorio, Daniel M en C<br />

Silva Ramos, José Manuel Ph D<br />

Urrutia Morales, Jorge Dr en C<br />

Viramontes Martínez, Francisco<br />

Unidad Académica <strong>de</strong> Medicina<br />

<strong>Veterinaria</strong> y Zootecnia, <strong>Universidad</strong><br />

Autónoma <strong>de</strong> <strong>Zacatecas</strong> (UAMVZ-<br />

UAZ)<br />

UAMVZ-UAZ<br />

UAMVZ-UAZ<br />

INIFAP - <strong>Zacatecas</strong><br />

Colegio <strong>de</strong> Postgraduados<br />

Facultad <strong>de</strong> Medicina <strong>Veterinaria</strong> y<br />

Zootecnia, <strong>Universidad</strong> Nacional <strong>de</strong><br />

Colombia<br />

Facultad <strong>de</strong> Medicina <strong>Veterinaria</strong> y<br />

Zootecnia, <strong>Universidad</strong> <strong>de</strong> los Llanos,<br />

Colombia<br />

Unidad Regional Universitaria <strong>de</strong> Zonas<br />

Áridas, <strong>Universidad</strong> Autónoma <strong>de</strong><br />

Chapingo<br />

UAMVZ-UAZ<br />

Facultad <strong>de</strong> Medicina <strong>Veterinaria</strong> y<br />

Zootecnia, <strong>Universidad</strong> Autónoma <strong>de</strong>l<br />

Estado <strong>de</strong> México<br />

UAMVZ-UAZ<br />

UAMVZ-UAZ<br />

UAMVZ-UAZ<br />

Campo Experimental San Luis. INIFAP<br />

UAMVZ-UAZ

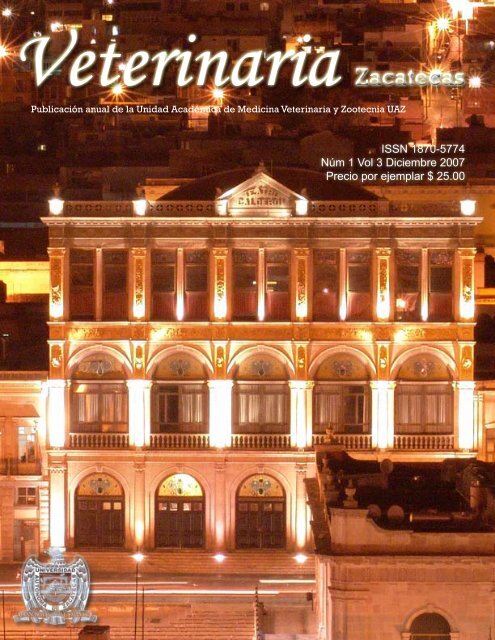

Nuestra Portada<br />

Teatro Fernando Cal<strong>de</strong>rón, Patrimonio <strong>de</strong> la <strong>Universidad</strong> Autónoma <strong>de</strong> <strong>Zacatecas</strong>.<br />

<strong>Zacatecas</strong>, Zac.<br />

Fotografía: Salvador Romo Gallardo, tel 8 99 24 29, e-mail jerg14@hotmail.com<br />

<strong>Veterinaria</strong> <strong>Zacatecas</strong> es una publicación anual <strong>de</strong> la Unidad Académica <strong>de</strong> Medicina<br />

<strong>Veterinaria</strong> y Zootecnia <strong>de</strong> la <strong>Universidad</strong> Autónoma <strong>de</strong> <strong>Zacatecas</strong>. ISSN: 1870-5774. Sólo<br />

se autoriza la reproducción <strong>de</strong> artículos en los casos que se cite la fuente.<br />

Correspon<strong>de</strong>ncia dirigirla a: <strong>Revista</strong> <strong>Veterinaria</strong> <strong>Zacatecas</strong>. <strong>Revista</strong> <strong>de</strong> la Unidad<br />

Académica <strong>de</strong> Medicina <strong>Veterinaria</strong> y Zootecnia <strong>de</strong> la <strong>Universidad</strong> Autónoma <strong>de</strong><br />

<strong>Zacatecas</strong>. Carretera Panamericana, tramo <strong>Zacatecas</strong>-Fresnillo Km 31.5. Apartados Postales<br />

9 y 11, Calera <strong>de</strong> Víctor Rosales, Zac. CP 98 500. Teléfono 01 (478) 9 85 12 55. Fax: 01<br />

(478) 9 85 02 02. E-mail: vetuaz@cantera.reduaz.mx. URL www.reduaz.mx/uaz.mvz<br />

Precio por cada ejemplar $25.00<br />

Distribución: Unidad Académica <strong>de</strong> Medicina <strong>Veterinaria</strong> y Zootecnia <strong>de</strong> la <strong>Universidad</strong><br />

Autónoma <strong>de</strong> <strong>Zacatecas</strong>.

CONTENIDO<br />

Artículos <strong>de</strong> revisión<br />

Review articles<br />

Primer parto en el ganado bovino productor <strong>de</strong> carne<br />

First calving in beef cows<br />

Alejandra Larios-Jiménez, Francisco Flores-Sandoval, Francisco Javier<br />

Escobar-Medina, Fe<strong>de</strong>rico <strong>de</strong> la Colina-Flores………………………………….<br />

1-12<br />

El comportamiento higiénico <strong>de</strong> la abeja Apis mellifera y su aplicación en el<br />

control <strong>de</strong> la varroosis<br />

Hygienic behavior in Apis mellifera bee on varroosis control<br />

Carlos Aurelio Medina-Flores…………………………………………………..<br />

13-20<br />

Artículos científicos<br />

Original research articles<br />

Eficiencia reproductiva en el ganado bovino productor <strong>de</strong> carne<br />

Reproductive efficiency in beef cow<br />

Alejandra Larios-Jiménez, Francisco Javier Escobar-Medina, Francisco Flores-<br />

Sandoval, Fe<strong>de</strong>rico <strong>de</strong> la Colina-Flores…………………………………………<br />

21-31<br />

Comportamiento reproductivo en ovejas <strong>de</strong> pelo a 22º 58’ N<br />

Reproductive behavior of hair ewes at 22º 58’ N<br />

Ángel Hernán<strong>de</strong>z-Santillán, Francisco Javier Escobar-Medina, Carlos<br />

Fernando Aréchiga-Flores, Fe<strong>de</strong>rico <strong>de</strong> la Colina-Flores.………………………<br />

33-38<br />

Efecto <strong>de</strong>l uso <strong>de</strong> almohadillas impregnadas con ácido fórmico sobre la<br />

infestación <strong>de</strong> Varroa <strong>de</strong>structor y la producción <strong>de</strong> miel<br />

José Luís Rodríguez Castillo, Yonatan Sandoval Olmos, Francisco Javier<br />

Escobar Medina, Carlos Fernando Aréchiga Flores, Francisco Javier Gutiérrez<br />

Piña, Jairo Iván Aguilera Soto, Carlos Aurelio Medina Flores............................<br />

39-44

PRIMER PARTO EN EL GANADO BOVINO PRODUCTOR DE CARNE<br />

Alejandra Larios-Jiménez, Francisco Flores-Sandoval, Francisco Javier Escobar-Medina, Fe<strong>de</strong>rico <strong>de</strong> la<br />

Colina-Flores<br />

Unidad Académica <strong>de</strong> Medicina <strong>Veterinaria</strong> y Zootecnia <strong>de</strong> la <strong>Universidad</strong> Autónoma <strong>de</strong> <strong>Zacatecas</strong><br />

E-mail: fescobar@uaz.edu.mx<br />

RESUMEN<br />

Las vaquillas tienen la capacidad <strong>de</strong> parir a los dos años <strong>de</strong> edad; esto <strong>de</strong>pen<strong>de</strong> <strong>de</strong> la edad a la pubertad y la<br />

concepción. La nutrición, raza <strong>de</strong>l animal, época <strong>de</strong>l año y presencia <strong>de</strong>l macho, entre otros factores, pue<strong>de</strong>n<br />

influir sobre la edad a la pubertad. En la presente revisión se discute esta parte <strong>de</strong> la fisiología reproductiva<br />

<strong>de</strong>l animal.<br />

Palabras clave: pubertad, primera concepción, primer parto, ganado bovino productor <strong>de</strong> carne<br />

<strong>Veterinaria</strong> <strong>Zacatecas</strong> <strong>2007</strong>; 3: 1-12<br />

INTRODUCCIÓN<br />

La eficiencia reproductiva óptima <strong>de</strong>l ganado<br />

productor <strong>de</strong> carne se registra cuando las vaquillas<br />

presentan su primer parto a los dos años <strong>de</strong> edad 1<br />

y en la vida adulta mantienen intervalos entre<br />

partos <strong>de</strong> 12 meses <strong>de</strong> duración. 2<br />

Para la edad óptima al primer parto se<br />

requiere la concepción entre 15 y 16 meses <strong>de</strong><br />

edad, y antes <strong>de</strong> ésta la presencia <strong>de</strong> la pubertad. 1<br />

Según los datos <strong>de</strong> la literatura, el avance genético<br />

ha permitido cambios importantes en el período<br />

prepuberal, las vaquillas en la actualidad<br />

presentan la pubertad a menor edad y peso que<br />

anteriormente, 3 también en algunos estudios se ha<br />

encontrado mayor influencia <strong>de</strong> la edad que <strong>de</strong>l<br />

peso en el momento <strong>de</strong> la concepción; 4 lo cual<br />

permite alimentar los animales con raciones <strong>de</strong><br />

menor concentración <strong>de</strong> energía y, por<br />

consiguiente, <strong>de</strong> menor precio; el resultado, se<br />

pue<strong>de</strong> aumentar la rentabilidad <strong>de</strong> las empresas<br />

gana<strong>de</strong>ras. 5<br />

En algunas explotaciones, los animales<br />

durante la mayor parte <strong>de</strong>l tiempo se alimentan<br />

con pastoreo en gramas nativas, únicamente se les<br />

ofrece complemento alimenticio en las<br />

temporadas <strong>de</strong> sequía. 6 Lo anterior invita al<br />

análisis <strong>de</strong> los aspectos más importantes <strong>de</strong>l<br />

período <strong>de</strong>l nacimiento al primer parto. En el<br />

presente estudio se revisó la información<br />

disponible <strong>de</strong> pubertad, primera concepción y<br />

primer parto en las vacas productoras <strong>de</strong> carne.<br />

PUBERTAD<br />

La pubertad en la becerra es el primer<br />

comportamiento <strong>de</strong> celo seguido <strong>de</strong> en un ciclo<br />

<strong>de</strong> 21 días <strong>de</strong> duración. La hembra <strong>de</strong>l<br />

nacimiento a poco antes <strong>de</strong> la pubertad<br />

permanece en un estado anovulatorio no cíclico:<br />

anestro. No se presenta el concierto hormonal<br />

entre hipotálamo, hipófisis y gónada que conduce<br />

a la ovulación. Esto se <strong>de</strong>be a la<br />

retroalimentación negativa <strong>de</strong>l estradiol sobre el<br />

hipotálamo; 7-11 con lo cual se reduce la secreción<br />

pulsátil <strong>de</strong> GnRH, y por consiguiente la<br />

disminución <strong>de</strong> la frecuencia <strong>de</strong> pulsos <strong>de</strong><br />

gonadotropinas <strong>de</strong>l lóbulo anterior <strong>de</strong> la<br />

hipófisis. 7,12 El resultado, los folículos ováricos<br />

no maduran a<strong>de</strong>cuadamente, su secreción <strong>de</strong><br />

estradiol no es suficiente para generar el pulso<br />

cíclico <strong>de</strong> GnRH/LH y la ovulación no se<br />

presenta. 13,14<br />

La concentración sanguínea <strong>de</strong><br />

gonadotropinas se incrementa <strong>de</strong> la semana 4 a<br />

14 <strong>de</strong> edad en las becerras, posteriormente se<br />

reduce y se mantiene a bajo nivel hasta la semana<br />

30, aproximadamente; 10,15-17 este incremento<br />

coinci<strong>de</strong> con el aumento en la población folicular<br />

y <strong>de</strong>l diámetro en el folículo <strong>de</strong> mayor tamaño,<br />

con el subsiguiente incremento en la secreción <strong>de</strong><br />

estradiol; 14,16,18-20 y se <strong>de</strong>be a la insuficiente<br />

sensibilidad <strong>de</strong>l hipotálamo al efecto inhibitorio<br />

<strong>de</strong>l estradiol, durante las primeras semanas <strong>de</strong><br />

vida <strong>de</strong>l animal. 21

FSH (ng/ml)<br />

Población folicular<br />

Diámetro (mm)<br />

16<br />

14<br />

12<br />

10<br />

8<br />

6<br />

4<br />

2<br />

0<br />

2 10 18 26 34 42 50 58<br />

Edad (semanas)<br />

Figura 1. Diámetro <strong>de</strong>l folículo dominante en las oleadas <strong>de</strong> crecimiento folicular<br />

en vaquillas. Primera ovulación a las 56.0 ± 1.2 semanas <strong>de</strong> edad 16,24<br />

1.6<br />

1.4<br />

1.2<br />

1<br />

0.8<br />

0.6<br />

0.4<br />

0.2<br />

0<br />

FSH<br />

Fol<br />

16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31<br />

Edad <strong>de</strong> la becerra (días)<br />

9<br />

8<br />

7<br />

6<br />

5<br />

4<br />

3<br />

2<br />

1<br />

0<br />

Figura 2. Concentración sérica <strong>de</strong> FSH y población <strong>de</strong> folículos ≥4mm <strong>de</strong><br />

diámetro, en becerras <strong>de</strong> 2 semanas <strong>de</strong> edad 16<br />

2

La concentración sérica <strong>de</strong> LH aumenta<br />

paulatinamente <strong>de</strong>spués <strong>de</strong>l la semana 30 <strong>de</strong> edad<br />

<strong>de</strong> las becerras, 14, 21,22 con el subsiguiente<br />

incremento en el diámetro <strong>de</strong>l folículo <strong>de</strong> mayor<br />

tamaño y la producción <strong>de</strong> estrógenos. 23 El<br />

diámetro <strong>de</strong>l folículo dominante (Figura 1) y su<br />

producción <strong>de</strong> estradiol se incrementan <strong>de</strong> oleada<br />

en oleada conforme la vaquilla se aproxima a la<br />

primera ovulación. 16,22-25 Los pulsos <strong>de</strong> secreción<br />

<strong>de</strong> LH aumentan en el período previo a la primera<br />

ovulación; 13,15 la FSH permanece al mismo<br />

nivel. 16,24 El crecimiento folicular en el período<br />

prepuberal se realiza en oleadas, 26,27 <strong>de</strong> la misma<br />

manera como se presenta en las vacas adultas, 28<br />

con aumento en la concentración sérica <strong>de</strong> FSH<br />

16, 27,29<br />

antes <strong>de</strong> cada oleada (Figura 2).<br />

La vaquilla <strong>de</strong>sarrolla su aparato genital<br />

<strong>de</strong> la semana 2 a la 14 y <strong>de</strong> la 34 al período previo<br />

a la pubertad, 20 <strong>de</strong> la misma manera como lleva a<br />

cabo el <strong>de</strong>sarrollo <strong>de</strong> folículos antrales. 19,22<br />

La primera ovulación se presenta <strong>de</strong>bido<br />

a la reducción <strong>de</strong> la retroalimentación negativa <strong>de</strong>l<br />

estradiol; 30-33 se disminuyen los receptores<br />

hipotalámicos para esta hormona, 22 lo cual<br />

permite la reactivación <strong>de</strong>l eje hipotálamohipófisis-gónada<br />

y la ovulación se presenta. El<br />

proceso en forma sucesiva es como sigue: se<br />

incrementa <strong>de</strong> la frecuencia <strong>de</strong> pulsos <strong>de</strong> GnRH en<br />

el hipotálamo, aumenta la secreción <strong>de</strong><br />

gonadotropinas en la hipófisis, 13,16,22,25,34 se<br />

incrementa el crecimiento folicular en el ovario<br />

con la subsiguiente producción <strong>de</strong><br />

estradiol, 16,23,24,25 particularmente algunos días<br />

antes <strong>de</strong> la primera ovulación; 14,23 el aumento <strong>de</strong>l<br />

nivel <strong>de</strong> esta hormona induce la secreción<br />

preovulatoria <strong>de</strong> LH 35,36 y se presenta la ovulación<br />

generalmente sin la manifestación <strong>de</strong> celo. 24,37<br />

Posteriormente se forma un cuerpo lúteo en cada<br />

folículo que ha ovulado, 38,39 don<strong>de</strong> se produce<br />

progesterona. La vida <strong>de</strong>l cuerpo lúteo producto<br />

<strong>de</strong> la primera ovulación generalmente es menor<br />

duración que en los ciclos ováricos normales,<br />

menor a 21 días. 24,37 La presencia <strong>de</strong> progesterona<br />

antes <strong>de</strong> las ovulaciones siguientes establece las<br />

condiciones apropiadas para la manifestación <strong>de</strong>l<br />

celo y se alcanza el equilibrio hormonal necesario<br />

para normalizar la duración <strong>de</strong> los ciclos<br />

estrales. 40 Los factores que influyen sobre la edad a<br />

la pubertad en las vaquillas son: nutrición, 41-45<br />

raza <strong>de</strong>l animal, 46 época <strong>de</strong>l año 47 y presencia <strong>de</strong>l<br />

macho. 48<br />

Nutrición<br />

La nutrición es un factor importante para<br />

<strong>de</strong>senca<strong>de</strong>nar la pubertad en el ganado bovino, las<br />

vaquillas alimentadas con cantida<strong>de</strong>s a<strong>de</strong>cuadas<br />

<strong>de</strong> energía inician su actividad ovárica cíclica más<br />

jóvenes que las mantenidas con restricciones<br />

energéticas en la dieta. 23,49,50 En la actualidad 3,4,41<br />

se pue<strong>de</strong> utilizar menor nivel <strong>de</strong> energía en la<br />

ración que como antiguamente se hacía 45,51 para<br />

obtener porcentajes aceptables <strong>de</strong> vaquillas<br />

púberes antes <strong>de</strong> la temporada <strong>de</strong> montas. Esto se<br />

<strong>de</strong>be al avance genético (ver más a<strong>de</strong>lante),<br />

antiguamente se procuraba <strong>de</strong>l 60 al 65% <strong>de</strong>l peso<br />

adulto en el animal al inicio <strong>de</strong> la temporada <strong>de</strong><br />

montas, 52 con el fin <strong>de</strong> asegurar la pubertad y<br />

porcentajes aceptables <strong>de</strong> gestación; actualmente<br />

las vaquillas presentan la pubertad a menor edad y<br />

peso, 53 lo cual permite disminuir la energía en la<br />

ración y como consecuencia reducir los costos <strong>de</strong><br />

alimentación. El incremento <strong>de</strong>l nivel <strong>de</strong> energía<br />

en la ración pue<strong>de</strong> inducir la pubertad precoz:<br />

inicio <strong>de</strong> la función ovárica cíclica en animales<br />

jóvenes, menores a 300 días <strong>de</strong> edad. 11,54,55<br />

La relación entre nutrición y<br />

reproducción probablemente se realice a través <strong>de</strong><br />

productos <strong>de</strong>l eje somatotrópico. En la vaca, la<br />

hormona <strong>de</strong>l crecimiento (GH) promueve la<br />

secreción hepática <strong>de</strong>l factor <strong>de</strong> crecimiento<br />

parecido a la insulina tipo I (IGF-I); 56-59 el cual<br />

pue<strong>de</strong> influir sobre la secreción <strong>de</strong> GnRH en las<br />

células <strong>de</strong>l hipotálamo 60-62 y LH en la hipófisis; 63-<br />

65 también incrementa la síntesis <strong>de</strong> receptores<br />

para gonadotropinas en las células ováricas y<br />

como consecuencia se aumenta la producción <strong>de</strong><br />

esteroi<strong>de</strong>s, 66-72 entre otras activida<strong>de</strong>s.<br />

Las vaquillas mejor alimentadas<br />

presentan mayor incremento <strong>de</strong> peso corporal y<br />

elevada concentración sanguínea <strong>de</strong>l IGF-I. 73 La<br />

presencia <strong>de</strong> este factor se ha relacionado con el<br />

aumento en la secreción <strong>de</strong> LH y la subsiguiente<br />

presentación <strong>de</strong> la pubertad en animales más<br />

jóvenes que en aquellos alimentados con dietas <strong>de</strong><br />

menor calidad. 74-76 El aumento <strong>de</strong> peso se<br />

relaciona con mayor crecimiento folicular y<br />

aumento en la secreción <strong>de</strong> estradiol en los<br />

folículos estrogénicamente activos. 23,55,77 En<br />

trabajos realizados in vitro, el IGF-I aumenta la<br />

función <strong>de</strong> la GnRH sobre las células <strong>de</strong>l lóbulo<br />

anterior <strong>de</strong> la hipófisis y las activida<strong>de</strong>s <strong>de</strong> las<br />

gonadotropinas sobre los ovarios. 65 La función <strong>de</strong><br />

GH en la vaquilla se ha <strong>de</strong>mostrado por medio <strong>de</strong><br />

la inmunización contra la hormona liberadora <strong>de</strong><br />

la hormona <strong>de</strong>l crecimiento; este tratamiento<br />

3

A Larios-Jiménez et al<br />

retarda la pubertad 78,79 y disminuye el crecimiento<br />

folicular. 80<br />

Los productos utilizados para<br />

incrementar la eficiencia alimenticia y por<br />

consiguiente el estrado nutricional <strong>de</strong>l animal,<br />

como los ionóforos, 81 reducen la edad a la<br />

pubertad en vaquillas. 82,83 Los ionóforos<br />

modifican la función metabólica y la proporción<br />

<strong>de</strong> ciertos microorganismos; 84 actúan sobre<br />

bacterias Gram positivas 85 y algunas Gram<br />

negativas; 86 también pue<strong>de</strong>n disminuir el<br />

porcentaje <strong>de</strong> protozoarios 84 y algunos hongos, 87<br />

bajo condiciones experimentales. El cambio en el<br />

ecosistema ruminal conduce al incremento <strong>de</strong>l<br />

ácido propiónico y la reducción <strong>de</strong> los ácidos<br />

ácetico y butírico, entre otras activida<strong>de</strong>s. 88-91 El<br />

incremento <strong>de</strong>l ácido propiónico en el rumen<br />

mejora la gluconeogénesis 84 e incrementa la<br />

capacidad <strong>de</strong> GnRH para secretar LH, 92,93 así<br />

como la influencia <strong>de</strong>l estradiol sobre la secreción<br />

preovulatoria <strong>de</strong> LH. 94 La infusión <strong>de</strong> propionato<br />

en el abomaso <strong>de</strong> vaquillas reduce la edad a la<br />

pubertad. 92<br />

Raza <strong>de</strong>l animal<br />

La edad y peso a la pubertad también<br />

varían <strong>de</strong> acuerdo a la raza <strong>de</strong>l animal. Las<br />

vaquillas <strong>de</strong> razas europeas generalmente alcanzan<br />

la pubertad más jóvenes y con menor peso que las<br />

Cebú, mestizas <strong>de</strong> Cebú o razas provenientes <strong>de</strong><br />

cruzamientos con Cebú; también se registran<br />

diferencias entre las razas europeas; las vaquillas<br />

Angus, por ejemplo, presentan la pubertad más<br />

jóvenes y con menor peso corporal que las<br />

Hereford. 46 En otros estudios también se han<br />

encontrado variaciones en la edad a la pubertad<br />

con relación a la raza <strong>de</strong>l animal. 3,43,95-98<br />

Las vaquillas pertenecientes a razas con<br />

mayor habilidad para la producción <strong>de</strong> leche<br />

presentan la pubertad con anterioridad a las<br />

hembras <strong>de</strong> otras razas. 99-101 Las vaquillas<br />

<strong>de</strong>scendientes <strong>de</strong> toros con mayor circunferencia<br />

escrotal 99,102 también alcanzan más jóvenes la<br />

pubertad. Por lo tanto, en el ganado bovino<br />

productor <strong>de</strong> carne se <strong>de</strong>bería esperar variaciones<br />

en la edad a la pubertad con relación a la<br />

información genética <strong>de</strong>l animal, más precoces las<br />

<strong>de</strong>scendientes <strong>de</strong> toros con mayor circunferencia<br />

escrotal y las portadoras <strong>de</strong> genes <strong>de</strong> razas con<br />

habilidad en la producción <strong>de</strong> leche; así como la<br />

presión <strong>de</strong> selección realizada para esta<br />

característica. Las vaquillas antiguamente<br />

presentaban la pubertad e iniciaban la temporada<br />

<strong>de</strong> montas con el 60 – 65 % <strong>de</strong> su esperado peso<br />

vivo, 103 en la actualidad algunas hembras lo hacen<br />

con el 50%. 104<br />

Época <strong>de</strong>l año<br />

El ganado bovino se reproduce<br />

continuamente, no presenta estacionalidad<br />

reproductiva. Sin embargo, la época <strong>de</strong>l año pue<strong>de</strong><br />

influir sobre el comportamiento reproductivo <strong>de</strong>l<br />

animal, 2,105-108 en este caso se analizará el período<br />

<strong>de</strong>l nacimiento a la pubertad. 108-110<br />

Se han encontrado variaciones en el<br />

comportamiento reproductivo a través <strong>de</strong>l año en<br />

las vaquillas. El ganado Brahman aumenta la<br />

inci<strong>de</strong>ncia <strong>de</strong> hembras púberes en la primavera,<br />

alcanza su máximo valor en el verano y disminuye<br />

durante el otoño; 47 probablemente en este trabajo<br />

se presentó el efecto <strong>de</strong> varios factores <strong>de</strong>l<br />

ambiente como disponibilidad <strong>de</strong> alimento,<br />

temperatura, humedad y fotoperiodo, y no<br />

exclusivamente el fotoperiodo como suce<strong>de</strong> en las<br />

especies con reproducción estacional. Los<br />

equinos, 111 ovinos 112 y caprinos, 113 entre otras<br />

especies <strong>de</strong> comportamiento reproductivo<br />

estacional, atien<strong>de</strong>n al fotoperiodo para presentar<br />

la pubertad.<br />

En el ganado bovino productor <strong>de</strong> carne,<br />

en el caso <strong>de</strong> mantener huella <strong>de</strong> la estacionalidad<br />

reproductiva <strong>de</strong>be presentar la pubertad bajo las<br />

condiciones <strong>de</strong>l fotoperiodo prevalecientes<br />

alre<strong>de</strong>dor <strong>de</strong>l equinoccio <strong>de</strong> otoño para permitir la<br />

concepción en otoño y se presenten los partos en<br />

la primavera <strong>de</strong>l año siguiente; la duración <strong>de</strong> la<br />

gestación en los bovinos es <strong>de</strong> 9 meses. 114 Las<br />

especies con reproducción estacional presentan<br />

sus partos en primavera, lo cual asegura mayor<br />

supervivencia <strong>de</strong> su <strong>de</strong>scen<strong>de</strong>ncia. 115 La<br />

frecuencia <strong>de</strong> pulsos y la concentración <strong>de</strong> LH son<br />

mayores alre<strong>de</strong>dor <strong>de</strong>l equinoccio <strong>de</strong> otoño en<br />

becerras recién nacidas, in<strong>de</strong>pendientemente <strong>de</strong>l<br />

mes <strong>de</strong> su nacimiento. 116 La edad a la pubertad es<br />

menor en las vaquillas nacidas en otoño en<br />

comparación con las nacidas en primavera <strong>de</strong>l<br />

mismo año, bajo condiciones <strong>de</strong> fotoperiodo<br />

natural; 30,110 las primeras reciben más jóvenes<br />

(alre<strong>de</strong>dor <strong>de</strong> 1 año <strong>de</strong> edad) la influencia <strong>de</strong>l<br />

fotoperiodo correspondiente al equinoccio <strong>de</strong><br />

otoño que las nacidas en primavera (alre<strong>de</strong>dor <strong>de</strong><br />

17 meses <strong>de</strong> edad). La edad a la pubertad también<br />

se reduce en las vaquillas mantenidas en cámaras<br />

<strong>de</strong> fotoperiodo con horas luz adicionales al<br />

fotoperiodo natural <strong>de</strong> otoño e invierno 109,110 y se<br />

retrasa con la reducción <strong>de</strong> la luminosidad. 110 La<br />

4

Eficiencia reproductiva en el ganado bovino productor <strong>de</strong> carne<br />

disminución <strong>de</strong> las horas luz <strong>de</strong>l día <strong>de</strong>mora la<br />

edad a la pubertad 95 y aumenta la inci<strong>de</strong>ncia <strong>de</strong><br />

anestro en vaquillas púberes. 117 El conjunto <strong>de</strong><br />

resultados anteriores indica variaciones en la edad<br />

a la pubertad con relación al fotoperiodo en las<br />

vaquillas productas <strong>de</strong> carne, con ten<strong>de</strong>ncia a<br />

presentar la pubertad alre<strong>de</strong>dor <strong>de</strong>l equinoccio <strong>de</strong><br />

otoño.<br />

Otra evi<strong>de</strong>ncia <strong>de</strong> la influencia <strong>de</strong>l<br />

fotoperiodo sobre la edad a la pubertad en la<br />

vaquilla productora <strong>de</strong> carne se recoge <strong>de</strong> un<br />

estudio realizado con aplicación <strong>de</strong> implantes <strong>de</strong><br />

melatonina, alre<strong>de</strong>dor <strong>de</strong>l solsticio <strong>de</strong> verano,<br />

durante 5 semanas. 118 La melatonina se produce<br />

en la glándula pineal 119 y es la hormona encargada<br />

<strong>de</strong> traducir el fotoperiodo en una señal<br />

hormonal. 120 El tratamiento aumentó el número <strong>de</strong><br />

vaquillas púberes en el año siguiente al<br />

tratamiento. 118<br />

Presencia <strong>de</strong>l macho<br />

La presencia <strong>de</strong>l macho sexualmente<br />

activo también pue<strong>de</strong> influir sobre la edad a la<br />

pubertad en vaquillas con crecimiento elevado y<br />

mo<strong>de</strong>rado, particularmente en las <strong>de</strong> mayor<br />

crecimiento; la influencia <strong>de</strong>l toro se incrementa<br />

conforme aumenta la tasa <strong>de</strong> crecimiento <strong>de</strong> las<br />

hembras; 48 lo mismo suce<strong>de</strong> con la infusión <strong>de</strong><br />

orina <strong>de</strong>l toro en la cavidad nasal <strong>de</strong> las<br />

vaquillas. 121 Resultados similares han encontrado<br />

otros autores en animales <strong>de</strong> diferente grupo<br />

genético. 122 PRIMERA CONCEPCIÓN<br />

La reducción <strong>de</strong> la edad a la pubertad en las<br />

vaquillas productoras <strong>de</strong> carne podría ser<br />

importante para incrementar su eficiencia<br />

reproductiva, la fertilidad se incrementa conforme<br />

transcurren los ciclos estrales, el 78% conciben al<br />

tercer estro y el 57% lo hacen en el celo<br />

puberal. 123 Lo mismo se ha encontrado en estudios<br />

realizados con transferencia embrionaria, la<br />

concepción es más elevada en transferencias<br />

realizadas en el tercer ciclo que en el puberal. 124<br />

Por lo tanto, edad más joven a la pubertad<br />

incrementa la posibilidad <strong>de</strong> concebir al inicio <strong>de</strong><br />

la temporada <strong>de</strong>stinada para las montas, entre más<br />

jóvenes a la pubertad mayor cantidad <strong>de</strong> ciclos<br />

estrales antes <strong>de</strong>l inicio <strong>de</strong> la temporada <strong>de</strong><br />

montas. El 89.8% y el 77.9% <strong>de</strong> las vaquillas<br />

concibieron en un estudio don<strong>de</strong> iniciaron la<br />

temporada <strong>de</strong> montas con el 58% y 51% <strong>de</strong>l peso<br />

adulto, respectivamente; el incremento en la<br />

duración <strong>de</strong> esta temporada <strong>de</strong> 45 a 60 días<br />

aumentó el porcentaje <strong>de</strong> concepción a 87.2 en las<br />

vaquillas con menor peso corporal; la mayoría <strong>de</strong><br />

las vaquillas menos pesadas que no concibieron<br />

(78.9%) permanecían en el período prepuberal al<br />

inicio <strong>de</strong> la temporada <strong>de</strong> montas, no habían<br />

presentado la pubertad. 104<br />

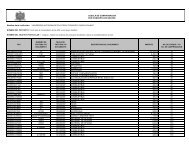

Cuadro 1. Raza predominante y edad promedio al primer parto en vaquillas mantenidas en pastoreo<br />

pertenecientes a 10 explotaciones <strong>de</strong> ganado bovino productor <strong>de</strong> carne 6<br />

Explotación Raza predominante Edad promedio al primer parto<br />

(días)<br />

1<br />

2<br />

3<br />

4<br />

5<br />

6<br />

7<br />

8<br />

9<br />

10<br />

Beefmaster<br />

Angus x Cebú<br />

Simental<br />

Charolais<br />

Gelbvieh<br />

Charolais<br />

Suizo x Charolais<br />

Angus x Suizo<br />

Charolais<br />

Angus<br />

804.26<br />

876.14<br />

802.23<br />

1324.49<br />

1065.06<br />

806.88<br />

716.03<br />

742.48<br />

884.10<br />

5

En otros estudios, sin embargo, no se ha<br />

observado la ten<strong>de</strong>ncia discutida en el párrafo<br />

anterior; las vaquillas <strong>de</strong> mayor aumento <strong>de</strong> peso<br />

durante el período prepuberal han presentado más<br />

jóvenes la pubertad, pero la concepción a la<br />

misma edad que hembras con menor<br />

incremento; 3,4 lo mismo se ha observado en las<br />

vaquillas con elevada y mo<strong>de</strong>rada ganancia <strong>de</strong><br />

peso y la presencia <strong>de</strong>l macho para inducir la<br />

pubertad. 48 Las diferencias entre los estudios<br />

citados probablemente se <strong>de</strong>ba al peso <strong>de</strong> los<br />

animales en el momento <strong>de</strong> iniciar la temporada<br />

<strong>de</strong> montas; en algunos estudios las vaquillas se<br />

han alimentado con raciones para baja ganancia <strong>de</strong><br />

peso durante las dos terceras partes <strong>de</strong>l período<br />

prepuberal y en la última con raciones para mayor<br />

aumento; bajo estas condiciones los animales<br />

pue<strong>de</strong>n presentar crecimiento compensatorio y<br />

llegar en la temporada <strong>de</strong> montas con buen estado<br />

nutricional que facilite la concepción. 4 En otros<br />

estudios, los animales se han alimentado con<br />

raciones <strong>de</strong> mo<strong>de</strong>rada reducción en el contenido<br />

<strong>de</strong> energía, lo cual conduce a ligera disminución<br />

<strong>de</strong>l peso; bajo esta situación las vaquillas pue<strong>de</strong>n<br />

retrasar la pubertad 3 o la presentan a la misma<br />

edad que las compañeras <strong>de</strong> mayor ganancia <strong>de</strong><br />

peso. 41 En todos los casos anteriores, se disminuye<br />

el costo <strong>de</strong> las raciones y se ahorran recursos<br />

<strong>de</strong>stinados para la alimentación.<br />

PRIMER PARTO<br />

Con base en la información <strong>de</strong>splegada, las<br />

vaquillas con el manejo citado <strong>de</strong>ben presentar su<br />

primer parto a los dos años <strong>de</strong> edad. Sin embargo,<br />

los sistemas <strong>de</strong> producción en algunos lugares se<br />

basan en el pastoreo <strong>de</strong> los animales y<br />

complemento alimenticio en la temporada <strong>de</strong><br />

sequía; <strong>de</strong> esta manera se ha mantenido la<br />

rentabilidad <strong>de</strong> las empresas <strong>de</strong>dicadas a la<br />

explotación <strong>de</strong>l ganado bovino productor <strong>de</strong> carne.<br />

En la Unidad Académica <strong>de</strong> Medicina <strong>Veterinaria</strong><br />

y Zootecnia <strong>de</strong> la <strong>Universidad</strong> Autónoma <strong>de</strong><br />

<strong>Zacatecas</strong> se está evaluando el comportamiento<br />

reproductivo <strong>de</strong>l ganado bovino en pastoreo, en<br />

uno <strong>de</strong> estos estudios 6 se encontró el primer parto<br />

a 987.8 días <strong>de</strong> edad, en vaquillas <strong>de</strong>10 hatos y <strong>de</strong><br />

diferente grupo genético; los animales en este<br />

estudio se fecundaron por medio <strong>de</strong> monta natural<br />

y la selección <strong>de</strong> los toros utilizados para este fin<br />

no se realizó con base en su tamaño testicular. Por<br />

lo tanto, el estudio se llevó a cabo en vaquillas sin<br />

aptitu<strong>de</strong>s para edad joven a la pubertad. Los<br />

<strong>de</strong>talles <strong>de</strong> esta información se pue<strong>de</strong>n observar en<br />

el Cuadro 1.<br />

REFERENCIAS<br />

1. Lesmeister JL, Burfening PJ, Blackwell<br />

RL. Date of first calving in beef cows<br />

and subsequent calf production. J Anim<br />

Sci 1973; 36: 1-6.<br />

2. Escobar FJ, Fernán<strong>de</strong>z-Baca S, Galina<br />

CS, Berruecos JM, Saltiel CA. Estudio<br />

<strong>de</strong>l intervalo entre partos en bovinos<br />

productores <strong>de</strong> carne en una explotación<br />

<strong>de</strong>l altiplano y otra en la zona tropical<br />

húmeda. Vet Méx 1982; 13: 53-60.<br />

3. Freetly HC, Cundiff LV. Postweaning<br />

growth and reproduction characteristics<br />

of heifers sired by bulls of seven breeds<br />

and raised on different levels of nutrition.<br />

J Anim Sci 1997; 75: 2841-2851.<br />

4. Lynch JM, Lamb GC, Miller BL, Brandt<br />

RT Jr, Cochran RC, Minton JE. Influence<br />

of timing of gain on growth and<br />

reproductive performance of beef<br />

replacement heifers. J Anim Sci 1997;<br />

75: 1715-1722.<br />

5. Funston RN, Deutscher GH. Comparison<br />

of target breeding weight and breeding<br />

date for replacement beef heifers and<br />

effects on subsequent reproduction and<br />

calf performance. J Anim Sci 2004; 82:<br />

3094-3099.<br />

6. Larios-Jiménez A, Flores-Sandoval F,<br />

Escobar-Medina FJ, <strong>de</strong> la Colina-Flores<br />

F. Eficiencia reproductiva <strong>de</strong>l ganado<br />

bovino productor <strong>de</strong> carne en pastoreo.<br />

Vet Zac <strong>2007</strong>; 3:<br />

7. Mosley WM, Dunn TG, Kaltenbach CC,<br />

Short RE, Staigmiller RB. Negative<br />

feedback control on luteinizing hormone<br />

secretion in prepubertal beef heifers at 60<br />

and 200 days of age. J Anim Sci 1984;<br />

58: 145-150.<br />

8. An<strong>de</strong>rson WJ, Forrest DW, Schulze AL,<br />

Kraemer DC, Bowen MJ, Harms PG.<br />

Ovarian inhibition of pulsatile luteinizing<br />

hormone secretion in prepubertal<br />

Holstein heifers. Domest Anim Endocrol<br />

1985; 2: 85-91.<br />

9. An<strong>de</strong>rson WJ, Forrest DW, Goff BA,<br />

Shaikh AA, Harms PG. Ontogeny of<br />

ovarian inhibition of pulsatile luteinizing<br />

hormone secretion in postnatal Hostein<br />

6

Eficiencia reproductiva en el ganado bovino productor <strong>de</strong> carne<br />

heifers. Domest Anim Endocrinol 1986;<br />

3: 107-116.<br />

10. Dodson SE, McLeord BJ, Haresing W,<br />

Peters AR, Lamming GE, Das D.<br />

Ovarian control of gonadotrophin<br />

secretion in the prepubertal heifer. Anim<br />

Reprod Sci 1989; 21: 1-10.<br />

11. Gasser CL, Bridges GA, Mussard ML,<br />

Grum DE, Kin<strong>de</strong>r JE, Day ML. Induction<br />

of precocious puberty in heifers III.:<br />

hastened reduction of estradiol negative<br />

feedback on secretion of luteinizing<br />

hormone. J Anim Sci 2006; 84: 2050-<br />

2056.<br />

12. Kiser TE, Kraeling RR, Rampacek GB,<br />

Landmeier BJ, Caudle AB, Champman<br />

JD. Luteinizing hormone secretion before<br />

and after ovariectomy in prepubertal and<br />

pubertal beef heifers. J Anim Sci 1981;<br />

53: 1545-1550.<br />

13. Day ML, Imakawa K, Garcia-Win<strong>de</strong>r M,<br />

Zalesky DD, Schanabacher BD, Kittok<br />

RJ, Kin<strong>de</strong>r JE. Endocrine mechanism of<br />

puberty in heifers: estradiol negative<br />

feedback regulation on luteinizing<br />

hormone secretion. Biol Reprod 1984;<br />

31: 332-341.<br />

14. Evans AC, Currie WD, Rawlings NC.<br />

Effects of naloxone on circulating<br />

gonadotropin concentrations in<br />

prepuberal heifers. J Reprod Fertil 1992;<br />

96: 847-855.<br />

15. Dodson SE, McLeod BJ, Haresing W,<br />

Peters AR, Lamming GE. Endocrine<br />

changes from birth to puberty in the<br />

heifer. J Reprod Fertil 1988; 82: 527-538.<br />

16. Evans AC, Adams GP, Rawlings NC.<br />

Follicular and hormonal <strong>de</strong>velopment in<br />

prepubertal heifers from 2 to 36 weeks of<br />

age. J Reprod Fertil 1994; 102: 463-470.<br />

17. Nakada K, Moriyoshi M, Nakao T,<br />

Watanabe G, Taya K. Changes in<br />

concentration of plasma immunoreactive<br />

follicle-stimulating hormone, luteinizing<br />

hormone, estradiol-17 , testosterone,<br />

progesterone, and inhibin in heifers from<br />

birth to puberty. Domest Anim<br />

Endocrinol 2000; 18: 57-69.<br />

18. Erickson BH. Development and<br />

senescence of the postnatal bovine ovary.<br />

J Anim Sci 1966; 25: 800-805.<br />

19. Desjardins C, Hafs HD. Levels of<br />

pituitary FSH and LH in heifers from<br />

birth through puberty. J Anim Sci 1968;<br />

27: 472-477.<br />

20. Honaramooz A, Aravindakshan J,<br />

Chandolia RK, Beard AP, Bartlewski<br />

PM, Pierson RA, Rawlings NC.<br />

Ultrasonographic evaluation of the prepubertal<br />

<strong>de</strong>velopment of the reproductive<br />

tract in beef heifers. Anim Reprod Sci<br />

2004; 80: 15-29.<br />

21. Schams D, Schallenberger E, Gombe S,<br />

Karg H. Endocrine patterns associated<br />

with puberty in male and female cattle. J<br />

Reprod Fertil 1981; 30 (Suppl): 103-110.<br />

22. Day ML, Imakura K, Wolfe PL, Kittok<br />

RJ, Kin<strong>de</strong>r JE. Endocrine mechanisms of<br />

puberty in heifers: role of hypothalamopituitary<br />

estradiol receptors in the<br />

negative feedback of estradiol on<br />

luteinizing hormone secretion. Biol<br />

Reprod 1987; 37: 1054-1065.<br />

23. Bergfeld EGM, Kojima FN, Cupp AS,<br />

Wehrman ME, Peters KE, Garcia-Win<strong>de</strong>r<br />

M, Kin<strong>de</strong>r JE. Ovarian follicular<br />

<strong>de</strong>velopment in prepubertal heifers is<br />

influenced by level of dietary energy<br />

intake. Biol Reprod 1994; 51: 1051-<br />

1057.<br />

24. Evans AC, Adams GP, Rawlings NC.<br />

Endocrine and follicular changes leading<br />

up to the first ovulation in prepubertal<br />

heifers. J Reprod Fertil 1994; 100: 187-<br />

194.<br />

25. Melvin EJ, Lindsey BR, Quintal-Franco<br />

J, Zanella E, Fike KE, Van Tassell CP,<br />

Kin<strong>de</strong>r JE. Estradiol, luteinizing<br />

hormone, and follicular stimulating<br />

hormone during waves of ovarian<br />

follicular <strong>de</strong>velopment in prepubertal<br />

cattle. Biol Reprod 1999; 60: 405-412.<br />

26. Hopper HW, Silcox RW, Byerley DJ,<br />

Kiser TE. Follicular <strong>de</strong>velopment in<br />

prepubertal heifers. Anim Reprod Sci<br />

1993; 31: 7-12.<br />

27. Adams GP, Evans AC, Rawling NC.<br />

Follicular waves and circulating<br />

gonadotropins in 8-old-month<br />

prepubertal heifers. J Reprod Fertil 1994;<br />

100: 27-33.<br />

28. Pierson RA, Ginther OJ. Ultrasonic<br />

imaging of the ovaries and uterus in<br />

cattle. Theriogenology 1988; 29: 21-38.<br />

29. Adams GP, Matteri RL, Kastelic JP, Ko<br />

JCH, Ginther OJ. Association between<br />

surges of follicle-stimulating hormone<br />

7

A Larios-Jiménez et al<br />

and the emergence of follicular waves in<br />

heifers. J Reprod Fertil 1992; 94: 177-<br />

188.<br />

30. Schillo KK, Dierschke DJ, Hauser ER.<br />

Regulation of luteinizing hormone<br />

secretion in prepubertal heifers:<br />

Increased threshold to negative feedback<br />

action of estradiol. J Anim Sci 1982; 54:<br />

325-336.<br />

31. Wolfe MW, Stumpf TT, Roberson MS,<br />

Wolfe PL, Kittok RJ. Estradiol<br />

influences on pattern of gonadotropin<br />

secretion in bovine males during the<br />

period of changes feedback in agematched<br />

females. Biol Reprod 1989; 41:<br />

626-634.<br />

32. Kurz SG, Dyer RM, Hu Y, Wright MD,<br />

Day ML. Regulation of luteinizing<br />

hormone secretion in prepubertal heifers<br />

fed an energy-<strong>de</strong>ficiency diet. Biol<br />

Reprod 1990; 43: 450-456.<br />

33. Day ML, An<strong>de</strong>rson LH. Current concepts<br />

on the control of puberty in cattle. J<br />

Anim Sci 1998; 76 (Suppl 3): 1-15.<br />

34. Day ML, Imakawa K, Zalesky DD,<br />

Kittok RJ, Kin<strong>de</strong>r JE. Effects of<br />

restriction of dietary energy intake during<br />

the prepubertal period on secretion of<br />

luteinizing hormone and responsiveness<br />

of the pituitary to luteinizing hormonereleasing<br />

hormone in heifers. J Anim Sci<br />

1986; 62: 1641-1648.<br />

35. Day ML, Imakawa K, Garcia-Win<strong>de</strong>r M,<br />

Kittok RJ, Schanbacher BD, Kin<strong>de</strong>r JE.<br />

Influence of prepubertal ovariectomy and<br />

estradiol replacement therapy on<br />

secretion of luteinizing hormone before<br />

and after pubertal age in heifers. Dom<br />

Anim Endocr 1986; 3: 17-25.<br />

36. Kin<strong>de</strong>r JE, Garcia-Win<strong>de</strong>r M, Imakawa<br />

K, Day ML, Zalesky DD, D’Occhio ML,<br />

Kittok RJ, Schanbacher BD. Influence of<br />

different estrogen doses on concentration<br />

of serum LH acute and chronic<br />

ovariectomized cow. J Anim Sci 1983;<br />

57 (Suppl 1): 350.<br />

37. Berardinelli JG, Dailey RA, Butcher RL,<br />

Inskeep EK. Source of progesterone prior<br />

to puberty in beef heifers. J Anim Sci<br />

1979; 1276-1280.<br />

38. Kesner JS, Padmanaghan V, Convey EM.<br />

Estradiol induces and progesterone<br />

inhibits the preovulatory surge of<br />

luteinizing hormone and follicle<br />

stimulating hormone in heifers. Biol<br />

Reprod 1982; 26: 571-578.<br />

39. Swason LV, McCarthy SK. Estradiol<br />

treatment and luteinizing hormone (LH)<br />

response of prepubertal Hostein heifers.<br />

Biol Reprod 1978; 18: 475-480.<br />

40. Rasby RJ, Day ML, Johnson SK, Kin<strong>de</strong>r<br />

JE, Lynch JM, Short RE, Wettemann RP,<br />

Hafs HS. Luteal function and estrus in<br />

peripubertal beef heifers treated with an<br />

intravaginal progesterone releasing<br />

<strong>de</strong>vice with or without of subsequent<br />

injection of estradiol. Theriogenology<br />

1998; 50: 55-63.<br />

41. Buskirk DD, Faulkner DB, Ireland FA.<br />

Increased postweaning gain of beef<br />

heifers enhances fertility and milk<br />

production. J Anim Sci 1995; 73: 937-<br />

946.<br />

42. Imakawa K, Day ML, Zalesky DD,<br />

Clutter A, Kittok RJ, Kin<strong>de</strong>r JE. Effects<br />

of 17-estradiol in diets varying in<br />

energy on secretion of luteinizing<br />

hormone in beef heifers. J Anim Sci<br />

1987; 64: 805-815.<br />

43. Ferrell CL. Effects of postweaning rate<br />

of gain on onset of puberty and<br />

productive performance of heifers of<br />

different breeds. J Anim Sci 1982; 55:<br />

1272-1283.<br />

44. Wiltbank JN, Kasson CW, Ingalls JE.<br />

Puberty in crossbred and straightbred<br />

beef heifers on two levels of feed. J<br />

Anim Sci 1969; 29: 602-605.<br />

45. Wiltbank JN, Roberts S, Nix J, Row<strong>de</strong>n<br />

L. Reproductive performance and<br />

profitability of heifers fed to weigh 272<br />

or 318 Kg at the start of the first breeding<br />

season. J Anim Sci 1985; 60: 25-34.<br />

46. Wiltbank JN, Sptizer JC. Investigaciones<br />

recientes sobre la reproducción regulada<br />

en el ganado bovino. Rev Mundial Zoot<br />

1978; 27: 30-35.<br />

47. Please D, Warnick AC, Koger M.<br />

Reproductive behavior of Bos indicus<br />

females in a subtropical environment. I.<br />

Puberty and ovulation frequency of<br />

Brahman and Brahman x British heifers.<br />

J Anim Sci 1968; 27: 94-100.<br />

48. Robertson MS, Wolfe MW, Stumpf TT,<br />

Werth LA, Cupp AS, Kojima N, Wokfe<br />

PL, Kittok RJ, Kin<strong>de</strong>r JE. Influence of<br />

growth rate and expose to bulls on age at<br />

8

Eficiencia reproductiva en el ganado bovino productor <strong>de</strong> carne<br />

puberty in beef heifers. J Anim Sci 1991;<br />

69: 2092-2098.<br />

49. Day ML, Imakawa K, Zalesky DD,<br />

Kittok RJ, Kin<strong>de</strong>r JE. Effects of<br />

restriction of dietary energy intake during<br />

the prepubertal period on secretion of<br />

luteinizing hormone and responsiveness<br />

of the pituitary to luteinizing hormonereleasing<br />

hormone in heifers. J Anim Sci<br />

1986; 62: 1641-1648.<br />

50. Romano MA, Barnabe VH, Kastelic JP,<br />

<strong>de</strong> Oliveira CA, Romano RM. Follicular<br />

dynamics in heifers during prepubertal<br />

and pubertal period kept un<strong>de</strong>r two levels<br />

of dietary energy intake. Reprod Domest<br />

Anim <strong>2007</strong>; 42: 616-622.<br />

51. Short RE, Bellows RA. Relationships<br />

among weight gains, age at puberty and<br />

reproductive performance in heifers. J<br />

Anim Sci 1971; 32: 127-131.<br />

52. Patterson DJ, Corah LR, Berthour JR,<br />

Higgins JJ, Kiracofe GH, Stevenson JS.<br />

Evaluation of reproductive traits in Bos<br />

taurus and Bos indicus crossbred heifers:<br />

Relationship of age at puberty to length<br />

of the postpartum interval to estrus. J<br />

Anim Sci 1992; 70: 1994-1999.<br />

53. Roberts AJ, Grings EE, MacNeil MD,<br />

Waterman RC, Alexan<strong>de</strong>r LJ, Geary TW.<br />

Reproductive performance of heifers<br />

offered ad libitum or restricted access to<br />

feed for a 140-d period after weaning.<br />

Western Section of Animal Science<br />

Proceedings <strong>2007</strong>; 58: 255-258.<br />

54. Gasser CL, Grum DE, Mussard ML,<br />

Fluhart FL, Kin<strong>de</strong>r JE, Day ML.<br />

Induction of precocious puberty in<br />

heifers I: enhanced secretion of<br />

luteinizing hormone. J Anim Sci 2006;<br />

84: 2035-2041.<br />

55. Gasser CL, Burke CR, Mussard ML,<br />

Behlke EJ, Grum DE, Kin<strong>de</strong>r JE, Day<br />

ML. Induction of precocious puberty in<br />

heifers II: advanced ovarian follicular<br />

<strong>de</strong>velopment. J Anim Sci 2006; 84:<br />

2042-2049.<br />

56. McGrath MF, Collier RJ, Clemmons DR,<br />

Busby WH, Sweeny CA, Krivi GG. The<br />

direct in vitro effect of insulin like<br />

growth factors (IGFs) on normal bovine<br />

mammary cell proliferation and<br />

production of IGF binding proteins.<br />

Endocrinology 1991; 129: 671-678.<br />

57. Cohick WS, Turner JD. Regulation of<br />

IGF binding proteins synthesis by bovine<br />

mammary epithelial cell line. J<br />

Endocrinol 1998; 157: 327-336.<br />

58. Liu JL, LeRoith D. Insulin-like growth<br />

factor I is essential for postnatal growth<br />

in response to growth hormone.<br />

Endocrinology 1999; 140: 5178-5184.<br />

59. Weber MS, Purup S, Vestergaard M,<br />

Ellis SE, Scn<strong>de</strong>rgard-An<strong>de</strong>rsen J, Akers<br />

RM, Sejrsen K. Contribution of insulinlike<br />

growth factor (IGF)-I and IGFbinding<br />

protein-3 to mitogenic activity in<br />

bovine mammary extracts and serum. J<br />

Endocrinol 1999; 161: 365-373.<br />

60. Zhen S, Zakaira M, Wolfe A, Radovick<br />

S. Regulation of gonadotropin-releasing<br />

hormone (GnRH) gene expression by<br />

insulin-like growth factor I in a cultured<br />

GnRH-expression neuronal cell line. Mol<br />

Endocrinol 1997; 11: 1145-1155.<br />

61. Longo KM, Sun Y, Gore AC. Insulinlike<br />

growth factor-I effects on<br />

gonadotropin-releasing hormone<br />

biosynthesis in GT1-7 cells.<br />

Endocrinology 1998; 139: 1125-1132.<br />

62. An<strong>de</strong>rson RA, Zwain IH, Arroyo A,<br />

Mellon PL, Yen SCS. The insulin-like<br />

growth factor system in the GT1-7 GnRH<br />

neuronal cell line. Neuroendocrinol<br />

1999; 70: 353-359.<br />

63. Adam CL, Findlay PA, Moore HA.<br />

Effects of insulin-like growth factors-I on<br />

luteinizing hormone secretion in sheep.<br />

Anim Reprod Sci 1997; 50: 45-56.<br />

64. Adam CL, Gadd TS, Findlay PA, Wathes<br />

DC. IGF-I stimulation of luteinizing<br />

hormone secretion, IGF-binding proteins<br />

(IGFBPs) and expression of mRNAs for<br />

IGFs, IGF receptors and IGFBPs in ovine<br />

pituitary gland. Endocrinology 2000;<br />

166: 247-254.<br />

65. Hashizime T, Kumahara A, Fujino M,<br />

Okada K. Insulin-like growth factor I<br />

enhances gonadotropin-releasing<br />

hormone-stimulated luteinizing hormone<br />

release from bovine anterior pituitary<br />

cells. Anim Reprod Sci 2002; 70: 13-21.<br />

66. Spicer LJ, Alpizar E, Echternkamp SE.<br />

Effects of insulin, IGF-I, and<br />

gonadotropins on bovine granulosa cell<br />

proliferation, progesterone production,<br />

estradiol production, and (or) IGF-I<br />

9

A Larios-Jiménez et al<br />

production in vitro. J Anim Sci 1993; 71:<br />

1232-1241.<br />

67. Spicer. LJ, Echternkamp SE. The ovarian<br />

insulin and insulin like growth factor<br />

system with an emphasis on domestic<br />

animals. Domest Anim Endocrinol 1995;<br />

12: 223-245.<br />

68. Adashi EY. Growth factors and ovarian<br />

function: the IGF-I paradigm. Horm Res<br />

1994; 42: 44-48.<br />

69. Adashi EY. The IGF family and<br />

folliculogenesis. J Reprod Immunol<br />

1998; 39: 13-19.<br />

70. Gong JG, McBri<strong>de</strong> D, Bramley TA,<br />

Webb R. Effects of recombinant bovine<br />

somatotrophin, insulin-like growth<br />

factor-I and insulin on the proliferation of<br />

bovine granulose cells in vitro. J<br />

Endocrinol 1993; 139: 67-75.<br />

71. Guidice LC. Insulin-like growth factor<br />

and ovarian follicular <strong>de</strong>velopment.<br />

Endocrine Rev 1992; 13: 641-669.<br />

72. Lucy MC. Regulation of ovarian<br />

follicular growth by somatotropin and<br />

insulin-like growth factors in cattle. J<br />

Dairy Sci 2000; 83: 1635-1647.<br />

73. Radcliff RP, Van<strong>de</strong>Haar MJ, Kobayashi<br />

Y, Sharma BK, Tucker HA, Lucy MC.<br />

Effect of dietary energy and<br />

somatotropin on components of the<br />

somatotropic axis in Holstein herifers. J<br />

Dairy Sci 2004; 87: 1229-1235.<br />

74. Granger AL, Wyatt WE, Craig WM,<br />

Thompson DL Jr, Hembry FG. Effects of<br />

breed and wintering diet on growth,<br />

puberty and plasma concentration of<br />

growth hormone and insulin-like growth<br />

factor 1 in heifers. Domest Anim<br />

Endocrinol 1989; 6: 253-262.<br />

75. Yelich JV, Wetteman RP, Dolezal HG,<br />

Lusby KS, Bishop DK, Spicer LJ. Effects<br />

of growth rate on carcass composition<br />

and lipid partitioning at puberty and<br />

growth hormone, insulin-like growth<br />

factor I, insulin, and metabolites before<br />

puberty in beef heifers. J Anim Sci 1995;<br />

73: 2390-2405.<br />

76. Yelich JV, Wetteman RP, Marston TT,<br />

Spicer LJ. Luteinizing hormone, growth<br />

hormone, insulin like growth factor-I,<br />

insulin and metabolites before puberty in<br />

heifers fed to gain at two rates. Domest<br />

Anim Endocrinol 1996; 13: 325-338.<br />

77. Spicer LJ, Enright WJ, Murphy MG,<br />

Roche JF. Effect of dietary intake on<br />

concentration of insulin-like growth<br />

factor-I in plasma and follicular fluid,<br />

and ovarian function in heifers. Domest<br />

Anim Endocrinol 1991; 8: 431-437.<br />

78. Cohick WS, Armstrong JD, Whitacre<br />

MD, Lucy MC, Harvey RW, Campbell<br />

RM. Ovarian expression of insulin-like<br />

growth factor-I (IGF-I), IGF binding<br />

proteins, and growth hormone (GH)<br />

receptor in heifers actively immunized<br />

against GH-releasing factors. Endocrinol<br />

1996; 137: 1670-1677.<br />

79. Schoppee PD, Armstrong JD, Harvey<br />

MA, Whitacre MD, Felix A, Campbell<br />

RM. Immunization against growth<br />

hormone releasing factor or chronic feed<br />

restriction initiated at 3.5 months of age<br />

reduces ovarian response at 6 months of<br />

age and <strong>de</strong>lays onset of puberty in<br />

heifers. Biol Reprod 1996; 55: 87-98.<br />

80. Simpson RB, Armstrong JD, Harvey<br />

RW, Miller DC, Heimer EP, Campbell<br />

RM. Effect of active immunization<br />

against growth hormone-releasing factor<br />

on growth and onset of puberty in beef<br />

heifers. J Anim Sci 1991; 69: 4914-4924.<br />

81. Goodrich RD, Garrett JE, Gast DR,<br />

Kirick MA, Larson DA, Meiske JC.<br />

Influence of monensin on the<br />

performance of cattle. J Anim Sci 1984;<br />

58: 1484-1498.<br />

82. Mosley WM, McCartor MM, Ran<strong>de</strong>l RD.<br />

Effects of monensin on growth and<br />

reproductive performance of beef heifers.<br />

J Anim Sci 1977; 45: 961-968.<br />

83. Mosley WM, Dunn TG, Kaltenbach CC,<br />

Short RE, Staigmiller RB. Relationship<br />

of growth and puberty of beef heifers fed<br />

monensin. J Anim Sci 1982; 55: 357-362.<br />

84. Schelling GT. Monensin mo<strong>de</strong> of action<br />

in the rumen. J Anim Sci 1984; 58: 1518-<br />

1527.<br />

85. Russell JB, Strobel HJ. Effects of<br />

additives on in vitro ruminal<br />

fermentation: a comparasion of monensin<br />

and bacitracin, another gram-positive<br />

antibiotic. J Anim Sci 1988; 66: 552-558.<br />

86. Morehead MC, Dawson KA. Some<br />

growth and metabolic characteristics of<br />

monensin-resistant strains of Prevotella<br />

(Bacteroi<strong>de</strong>s) ruminicola. Appl Environ<br />

Microbol 1992; 58: 1617-1623.<br />

10

Eficiencia reproductiva en el ganado bovino productor <strong>de</strong> carne<br />

87. Cann IKO, Kobayashi Y, Onada A,<br />

Wakita M, Hoshino S. Effects of some<br />

ionophore antibiotics and polyoxins on<br />

the growth of anaerobic rumen fungi. J<br />

Appl Bacteriol 1993; 74: 127-133.<br />

88. Richardson LF, Raun AP, Potter EL,<br />

Cooley CO, Rathmacher RP. Effect of<br />

monensin in rumen fermentation in vivo<br />

and in vitro. J Anim Sci 1976; 43: 657-<br />

664.<br />

89. Davis GV. Effects of lasalocid sodium on<br />

the performance of finishing steers. J<br />

Anim Sci 1978; 47 (Suppl 1): 414.<br />

90. Bartley EE, Herod EL, Bechtle RM,<br />

Sapienza DA, Brent BE, Davidovich A.<br />

Effect of monensin or lasalocid, with and<br />

without niacin or amicloral, on rumen<br />

fermentation and feed efficiency. J Anim<br />

Sci 1979; 49: 1066-1075.<br />

91. Thonney ML, Hei<strong>de</strong> EK, Duhaime DJ,<br />

Hand RJ, Perosio DJ. Growth, feed<br />

efficiency and metabolite concentration<br />

of cattle fed high forage diets with<br />

lasalocid or monensin supplements. J<br />

Anim Sci 1981; 52: 427-433.<br />

92. Rutter LM, Ran<strong>de</strong>l RD, Schelling GT,<br />

Forrest DW. Effect of abomasal infusion<br />

of propionate on the GnRH-induced<br />

luteinizng hormone release in prepuberal<br />

heifers. J Anim Sci 1983; 56: 1167-1173.<br />

93. Ran<strong>de</strong>l RD. Rho<strong>de</strong>s RC III. The effect of<br />

dietary monensin on the luteinizing<br />

hormone response of prepubertal heifers<br />

given a multiple gonadotropin-releasing<br />

hormone challenge. J Anim Sci 1980; 51:<br />

925-931.<br />

94. Ran<strong>de</strong>l RD, Rutter LM, Rho<strong>de</strong>s RC III.<br />

Effect of monensin on the estrogeninduced<br />

LH surge in prepubetal heifers. J<br />

Anim Sci 1982; 54: 806-810.<br />

95. Grass JA, Hansen PJ, Rutledge JJ,<br />

Hauser ER. Genotype-environmental<br />

interactions on reproductive traits of<br />

bovine felames: I. Age at puberty as<br />

influenced by breed, breed of sire, dietary<br />

regimen and season. J Anim Sci 1982;<br />

55: 1441-1457.<br />

96. Gregory KE, Laster DB, Cundiff LV,<br />

Koch RM, Smith GM. Heterosis and<br />

breed maternal and transmitted effects in<br />

beef cattle. II. Growth and rate puberty in<br />

females. J Anim Sci 1978; 47: 1042-<br />

1053.<br />

97. Gregory KE, Laster DB, Cundiff LV,<br />

Smith GM, Koch RM. Characterization<br />

of biological types of cattle-cycle III: II.<br />

Growth rate and puberty in females. J<br />

Anim Sci 1979; 49: 461-471.<br />

98. Chenoweth PJ. Aspects of reproduction<br />

in female Bos indicus cattle: a review.<br />

Aust Vet J 1994; 71: 422-426.<br />

99. Martin LC, Brinks JS, Bourdin RM,<br />

Cundiff LV. Genetic effects on beef<br />

heifer puberty and subsequent<br />

reproduction. J Anim Sci 1992; 70: 4006-<br />

4017.<br />

100. Laster DB, Smith GM, Gregory KE.<br />

Characterization of biological type of<br />

cattle. IV. Postweaning growth and<br />

puberty of heifers. J Anim Sci 1976; 43:<br />

63-70.<br />

101. Laster DB, Smith GM, Cundiff LV,<br />

Gregory KE. Characterization of<br />

biological type of cattle (cycle II). II.<br />

Postweaning growth and puberty of<br />

heifers. J Anim Sci 1979; 48: 500-508.<br />

102. Morris CA, Baker RL, Cullen NG.<br />

Genetic correlations between pubertal<br />

traits in bulls and heifers. Livest Prod Sci<br />

1992; 31: 221-234.<br />

103. Patterson DJ, Perry RC, Kiracofe GH,<br />

Bellows RA, Staigmiller RB, Corah LR.<br />

Management consi<strong>de</strong>rations in heifer<br />

<strong>de</strong>velopment and puberty. J Anim Sci<br />

1992; 70: 4018-4035.<br />

104. Martin JL, Creighton KW, Musgrave JA,<br />

Klopfenstein TJ, Clark RT, Adams DC,<br />

Funston RN. Effect of prebreeding body<br />

weight or progestin exposure before<br />

breeding on beef heifer performance<br />

through the second breeding season. J<br />

Anim Sci 2008; 86: 451-459.<br />

105. King GJ, Macleod GK. Reproductive<br />

function in beef cows calving in the<br />

spring or fall. Anim Reprod Sci 1984; 6:<br />

255-266.<br />

106. Critser JK, Miller KF, Gunstt FC,<br />

Ginther OJ. Seasonal LH profile in<br />

ovariectomized cattle. Theriogenology<br />

1983; 19: 181-191.<br />

107. Critser JK, Lindstorm MJ, Hineshelwood<br />

MM, Hauser ER. Effect of photoperiod<br />

on LH, FSH and prolactin patterns in<br />

ovariectomized estradiol-treated heifers.<br />

J Reprod Fertil 1987; 79: 599-608.<br />

108. Schillo KK, Hall JB, Hileman SM.<br />

Effects of nutrition and season on the<br />

11

A Larios-Jiménez et al<br />

onset of puberty in the beef heifer. J<br />

Anim Sci 1992; 70: 3994-4005.<br />

109. Hansen PJ, Kamwanja LA, Hauser ER.<br />

Photoperiod infuences age at puberty of<br />

heifers. J Anim Sci 1983; 57: 985-992.<br />

110. Schillo KK, Hansen PJ, Kamwanja LA,<br />

Dierschke DJ, Hauser ER. Influence of<br />

season on sexual <strong>de</strong>velopment in heifers:<br />

age at puberty as related to growth and<br />

serum concentration of gonadotropins,<br />

prolactin, thyroxine and progesterone.<br />

Biol Reprod 1983; 28: 329-341.<br />

111. Brown-Douglas CG, Firth EC, Parkinson<br />

TJ, Fennessy PF. Onset of puberty in<br />

pasture-raised Throughbreeds born in<br />

southern hemisphere spring and autumn.<br />

Equine Vet J 2004; 36: 499-504.<br />

112. Foster DL. Puberty in sheep. In: Knobil<br />

E, Neil JD, editors. The Physiology or<br />

Reproduction. New York: Raven Press,<br />

1994: 411-451.<br />

113. Erario A, Escobar FJ, Rincón RM, <strong>de</strong> la<br />

Colina F, Meza C. Efecto <strong>de</strong>l fotoperiodo<br />

sobre la edad a la pubertad en la cabra.<br />

<strong>Revista</strong> Chapingo Serie Zonas Áridas<br />

2004; 155-158.<br />

114. An<strong>de</strong>rsen H, Plum M. Gestation length<br />

and birth weight in cattle and buffaloes: a<br />

review. J Dairy Sci 1965; 48: 1224-1235.<br />

115. Bronson FH, Hei<strong>de</strong>man PD. Seasonal<br />

regulation of reproduction in mammals.<br />

In: Knobil E, Neil JD, editors. The<br />

Physiology of Reproduction. New York:<br />

Raven Press, 1994: 541-584.<br />

116. Schillo KK, Dierschke DJ, Hauser ER.<br />

Influences of month of birth and age on<br />

patterns of luteinizing hormone secretion<br />

in prepubertal heifers. Theriogenology<br />

1982; 18: 593-598.<br />

117. Stahringer RB, Neuendorff DA, Ran<strong>de</strong>l<br />

RD. Seasonal variations in characteristics<br />

of estrus cycles in pubertal Brahman<br />

heifers. Theriogenology 1990; 34: 407-<br />

415.<br />

118. Tortonese DJ, Inskeep EK. Effects of<br />

melatonin treatment on the attainment of<br />

puberty in heifers. J Anim Sci 1992; 70:<br />

2822-2827.<br />

119. Moore RY. Neural control of the pienal<br />

gland. Behav Brain Res 1996; 73: 125-<br />

130.<br />

120. Arendt J. Melatonin and the pineal gland:<br />

influence on mammalian seasonal and<br />

circadian physiology. Rev Reprod 1998;<br />

3: 13-22.<br />

121. Izard MK, Van<strong>de</strong>nbergh JG. The effects<br />

of bull urine on puberty and calving date<br />

in crossbred beef heifers. J Anim Sci<br />

1982; 55: 1160-1168.<br />

122. Rekwot P, Ogwu D, Oyedipe E, Sekoni<br />

V. Effect of bull exposure and body<br />

growth on onset of puberty in Bunaji and<br />

Friesian x Bunaji heifers. Reprod Nutr<br />

Dev 2000; 40: 359-367.<br />

123. Byerley DJ, Staigmiller RB, Berardinelli<br />

JG, Short RE. Pregnancy rates of beef<br />

heifers bred either on puberal or third<br />

estrus. J Anim Sci 1987; 65: 645-650.<br />

124. Staigmiller RB, Bellows RA, Short RE,<br />

MacNeil MD, Hall JB, Phelps DA,<br />

Bartlett SE. Concepción rates in beef<br />

heifers following embryo transfer at the<br />

pubertal or third estrus. Theriogenology<br />

1993; 39: 315.<br />

ABSTRACT<br />

Larios-Jiménez A, Flores-Sandoval F, Escobar-Medina FJ, <strong>de</strong> la Colina-Flores F. First calving in beef<br />

cows. Heifers may have their first calf at 24 months of age; <strong>de</strong>pending on their age at puberty and first<br />

conception. Nutrition, breed, season and exposure to the bull may as well influence the age at puberty. This<br />

topic of reproductive physiology is focus of the present review. <strong>Veterinaria</strong> <strong>Zacatecas</strong> <strong>2007</strong>; 3: 1-12<br />

Key words: puberty, first conception, first calving, beef cow<br />

12

EL COMPORTAMIENTO HIGIÉNICO DE LA ABEJA APIS MELLIFERA Y SU APLICACIÓN EN<br />

EL CONTROL DE LA VARROOSIS<br />

Carlos Aurelio Medina-Flores<br />

Unidad Académica <strong>de</strong> Medicina <strong>Veterinaria</strong> y Zootecnia <strong>de</strong> la <strong>Universidad</strong> Autónoma <strong>de</strong> <strong>Zacatecas</strong>.<br />

E-mail: carlosmedina@uaz.edu.mx<br />

RESUMEN<br />

El comportamiento higiénico se consi<strong>de</strong>ra como uno <strong>de</strong> los principales mecanismos <strong>de</strong> tolerancia <strong>de</strong> la abeja<br />

Apis mellifera contra el ácaro Varroa <strong>de</strong>structor. En el presente trabajo se discuten los factores que influyen<br />

en la expresión <strong>de</strong> este comportamiento <strong>de</strong> la abeja Apis mellifera y su relación con el control <strong>de</strong> Varroa<br />

<strong>de</strong>structor.<br />

Palabras clave: Apis mellifera, Comportamiento higiénico, Varroa <strong>de</strong>structor<br />

<strong>Veterinaria</strong> <strong>Zacatecas</strong> <strong>2007</strong>; 3: 13-20<br />

INTRODUCCIÓN<br />

Las abejas melíferas (Apis mellifera), reutilizan<br />

las celdas <strong>de</strong> sus panales para alojar varias<br />

generaciones <strong>de</strong> crías, lo cual no suce<strong>de</strong> con otros<br />

insectos sociales como las abejas sin aguijón y<br />

abejorros. 1,2<br />

La limpieza <strong>de</strong> estas celdas <strong>de</strong>spués <strong>de</strong><br />

cada ciclo <strong>de</strong> cría es una actividad importante<br />

realizada por las abejas adultas, sin embargo,<br />

cuando una larva o pupa muere en el interior <strong>de</strong> la<br />

celda durante su <strong>de</strong>sarrollo se presenta un<br />

problema <strong>de</strong> limpieza <strong>de</strong>ntro <strong>de</strong> la colonia. 3<br />

Otra actividad <strong>de</strong> limpieza <strong>de</strong>ntro <strong>de</strong>l<br />

nido <strong>de</strong> Apis mellifera es el comportamiento<br />

higiénico, esta actividad la <strong>de</strong>sarrollan<br />

principalmente abejas <strong>de</strong> 15 y 17 días <strong>de</strong> edad 2 , y<br />

consiste en <strong>de</strong>tectar, <strong>de</strong>sopercular y remover <strong>de</strong><br />

sus celdas a la cría enferma o muerta. 3,4 Este<br />

comportamiento, es un mecanismo utilizado para<br />

la <strong>de</strong>fensa en contra <strong>de</strong> enfermeda<strong>de</strong>s <strong>de</strong> la cría<br />

como loque americana (Paenibacillus larvae<br />

larvae), cría calcárea (Ascosphaera apis) 1,5 y<br />

contra el ácaro Varroa <strong>de</strong>structor. 6<br />

Los métodos más efectivos para el<br />

control <strong>de</strong> Varroa <strong>de</strong>structor consisten en el uso<br />

<strong>de</strong> productos químicos los cuales son costosos,<br />

provocan que el ácaro <strong>de</strong>sarrolle resistencia y<br />

contaminan los productos <strong>de</strong> la colmena,<br />

afectando su aceptación en el mercado. Lo más<br />

a<strong>de</strong>cuado es promover el <strong>de</strong>sarrollo <strong>de</strong>l<br />

comportamiento higiénico, para lo cual se requiere<br />

estudiarlo y establecer las condiciones apropiadas<br />

para su ejecución por las abejas. En el presente<br />

trabajo se discuten los aspectos relacionados con<br />

el estudio <strong>de</strong>l comportamiento higiénico en<br />

colonias <strong>de</strong> abejas melíferas así como su<br />

aplicación en el control <strong>de</strong> la varroosis.<br />

INFLUENCIA GENÉTICA Y AMBIENTAL<br />

DEL COMPORTAMIENTO HIGIÉNICO<br />

Uno <strong>de</strong> los trabajos más importantes sobre<br />

comportamiento higiénico lo realizó<br />

Rothenbuhler, 8 el cual <strong>de</strong>terminó que su <strong>de</strong>sarrollo<br />

<strong>de</strong>pendía <strong>de</strong> la presencia <strong>de</strong> dos loci recesivos en<br />

homocigocis. Posteriormente fue reportado que la<br />

herencia <strong>de</strong> esta conducta pue<strong>de</strong> ser controlada<br />

por más <strong>de</strong> dos loci recesivos. 9,10<br />

Recientemente Lapidge et al. 11 por medio<br />

<strong>de</strong> técnicas moleculares <strong>de</strong>tectaron siete loci, <strong>de</strong><br />

los cuales tres <strong>de</strong> ellos fueron asociados solamente<br />

con la <strong>de</strong>soperculación <strong>de</strong> las celdas, y cuatro con<br />

influencia en el proceso <strong>de</strong> remoción.<br />

Por otro lado, los valores <strong>de</strong><br />

heredabilidad <strong>de</strong>l comportamiento higiénico han<br />

sido variables. 12 basados en la regresión madre–<br />

hija reportan un valor <strong>de</strong> 0.18 <strong>de</strong> heredabilidad <strong>de</strong><br />

la cría infestada con un ácaro Varroa <strong>de</strong>structor,<br />

mientras que para la remoción <strong>de</strong> la cría muerta<br />

usando el método <strong>de</strong> punción <strong>de</strong> la celda es <strong>de</strong><br />

0.36. 12 Contrariamente, Harbo y Harris 13 basados<br />

en la remoción <strong>de</strong> la cría muerta por el método <strong>de</strong><br />

enfriamiento reportan 0.65, mientras que la<br />

heredabilidad calculada bajo condiciones <strong>de</strong><br />

laboratorio para el <strong>de</strong>soperculado <strong>de</strong> las celdas fue

C A Medina-Flores<br />

<strong>de</strong> 0.14, y para la remoción <strong>de</strong> la cría muerta fue<br />

<strong>de</strong> 0.02. 14 La expresión <strong>de</strong>l comportamiento<br />

higiénico <strong>de</strong>pen<strong>de</strong> <strong>de</strong> la edad <strong>de</strong> la cría, <strong>de</strong> la<br />

proporción <strong>de</strong> abejas higiénicas <strong>de</strong>ntro <strong>de</strong> la<br />

colonia, 1,15,16 <strong>de</strong> la cantidad <strong>de</strong> néctar 17-19 y <strong>de</strong>l<br />

polen disponible. 20 Contrario a lo registrado por<br />

Spivak y Gilliam, 1 el comportamiento higiénico,<br />

no está influenciado por la “fortaleza” <strong>de</strong> las<br />

colonias, medida con base a cantidad <strong>de</strong> panales<br />

con abejas adultas y cría. 5,21<br />

La remoción aumenta con el incremento<br />

<strong>de</strong>l número <strong>de</strong> ácaros (Varroa <strong>de</strong>structor) por<br />

celda, por la presencia <strong>de</strong> virus en el parásito 14 y<br />

por el tipo <strong>de</strong> panal; pupas infestadas y alojadas en<br />

panales <strong>de</strong> plástico son removidas más<br />

rápidamente que las pupas infestadas que se<br />

encuentran en panales <strong>de</strong> cera. 6,22,23<br />

DETERMINACIÓN Y FRECUENCIA DEL<br />

NIVEL DE COMPORTAMIENTO<br />

HIGIÉNICO EN POBLACIONES DE<br />

COLONIAS DE A. MELLIFERA<br />

La i<strong>de</strong>ntificación <strong>de</strong> colonias con el<br />

comportamiento higiénico se ha realizado<br />

infectando a la cría con esporas <strong>de</strong> P. larvae, 8<br />

matando a la cría puncionándolas a través <strong>de</strong>l<br />