facultad de medicina societas internationalis historiae medicinae

facultad de medicina societas internationalis historiae medicinae

facultad de medicina societas internationalis historiae medicinae

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

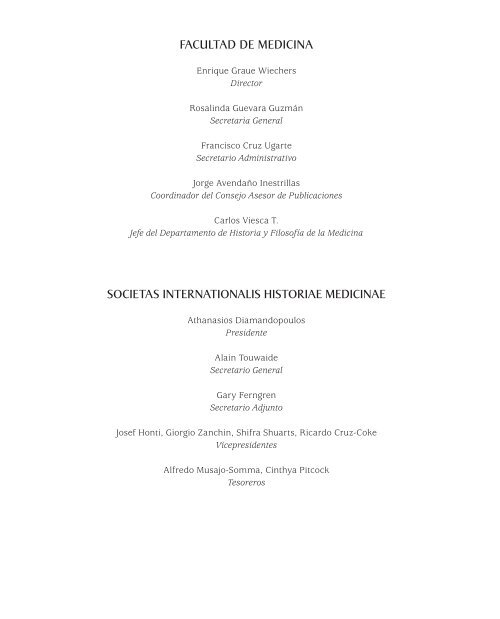

FACULTAD DE MEDICINA<br />

Enrique Graue Wiechers<br />

Director<br />

Rosalinda Guevara Guzmán<br />

Secretaria General<br />

Francisco Cruz Ugarte<br />

Secretario Administrativo<br />

Jorge Avendaño Inestrillas<br />

Coordinador <strong>de</strong>l Consejo Asesor <strong>de</strong> Publicaciones<br />

Carlos Viesca T.<br />

Jefe <strong>de</strong>l Departamento <strong>de</strong> Historia y Filosofía <strong>de</strong> la Medicina<br />

SOCIETAS INTERNATIONALIS HISTORIAE MEDICINAE<br />

Athanasios Diamandopoulos<br />

Presi<strong>de</strong>nte<br />

Alain Touwai<strong>de</strong><br />

Secretario General<br />

Gary Ferngren<br />

Secretario Adjunto<br />

Josef Honti, Giorgio Zanchin, Shifra Shuarts, Ricardo Cruz-Coke<br />

Vicepresi<strong>de</strong>ntes<br />

Alfredo Musajo-Somma, Cinthya Pitcock<br />

Tesoreros

ANALECTA HISTORICO MEDICA<br />

VI<br />

Guest Editors<br />

Massimo Pandolfi y Paolo Vanni<br />

Año VI, No. 1 2008<br />

SOCIETAS<br />

INTERNATIONALIS<br />

HISTORIAE MEDICINAE

ANALECTA HISTORICO MEDICA<br />

Revista <strong>de</strong>l Departamento <strong>de</strong> Historia<br />

y Filosofía <strong>de</strong> la Medicina <strong>de</strong> la Facultad<br />

<strong>de</strong> Medicina <strong>de</strong> la UNAM y la Sociedad<br />

Internacional <strong>de</strong> Historia <strong>de</strong> la Medicina<br />

Comité Editorial<br />

EDI T OR E S<br />

Carlos Viesca T. y Jean-Pierre Tricot<br />

COE DI T OR E S<br />

Andrés Aranda y Diana Gasparon<br />

CUI DA D O DE LA EDI CIÓN<br />

Carlos Viesca T.<br />

DISEÑO, FOR M ACIÓN EDI T OR I AL<br />

E I M PR E S IÓN<br />

Gráfica, Creatividad y Diseño S.A. <strong>de</strong> C.V.<br />

grafcrea@prodigy.net.mx<br />

© Derechos reservados conforme a la ley<br />

DEPARTAMENTO DE HISTORIA Y FILOSOFÍA<br />

SOCIETAS<br />

DE LA MEDICINA DE LA FACULTAD DE<br />

MEDICINA DE LA UNIVERSIDAD NACIONAL<br />

AUTÓNOMA DE MÉXICO.<br />

Brasil 33, Col. Centro, 06020<br />

México, D.F., Tel. 5529.7542<br />

Publicación anual. Número <strong>de</strong> Certificado<br />

<strong>de</strong> Reserva otorgado por el Instituto<br />

Nacional <strong>de</strong>l Derecho <strong>de</strong> Autor: 04-2005-<br />

112310281700-102. Número <strong>de</strong><br />

Certificado <strong>de</strong> Licitud <strong>de</strong> Título: en<br />

trámite. Número <strong>de</strong> Certificado <strong>de</strong> Licitud<br />

<strong>de</strong> Contenido: en trámite.<br />

ISSN: 1870-3488<br />

Precio: $300, USD30<br />

Patricia Aceves<br />

Xóchitl Martínez Barbosa<br />

Rolando Neri Vela<br />

Mariblanca Ramos <strong>de</strong> Viesca<br />

Ana Cecilia Rodríguez <strong>de</strong> Romo<br />

Martha Eugenia Rodríguez Pérez<br />

Gabino Sánchez Rosales<br />

José Sanfilippo<br />

INTERNATIONALIS<br />

Comité Editorial Internacional<br />

Philippe Albou (Francia)<br />

Klaus Bergdolt (Alemania)<br />

German Berrios (UK)<br />

J. S. G. Blair (UK)<br />

Antonio Carreras Panchón (España)<br />

Pedro Chiancone (Uruguay)<br />

Ricardo Cruz-Cocke M. (Chile)<br />

Gregorio Delgado (Cuba)<br />

José Luis Doria (Portugal)<br />

Gary Ferngren (Estados Unidos <strong>de</strong> Norteamérica)<br />

Miguel González Guerra (Venezuela)<br />

Alfredo Kohn Loncarica (Argentina) †<br />

Alain Léllouch (Francia)<br />

César Lorenzano (Argentina)<br />

José Luis Peset (España)<br />

Robin Price (UK)<br />

Francisco Javier Puerto Sarmiento (España)<br />

Merce<strong>de</strong>s S. Granjel (España)<br />

Tatiana Sorokhina (Rusia)<br />

Alain Touwai<strong>de</strong> (Estados Unidos <strong>de</strong> Norteamérica)<br />

Paolo Aldo Rossi (Italia)<br />

David Wright (UK)<br />

Giorgio Zanchin (Italia)<br />

HISTORIAE MEDICINAE<br />

Queda estrictamente prohibida la<br />

reproducción total o parcial <strong>de</strong> esta<br />

publicación, en cualquier forma o medio,<br />

sea <strong>de</strong> la naturaleza que sea, sin el<br />

permiso previo, expreso y por escrito<br />

<strong>de</strong>l titular <strong>de</strong> los <strong>de</strong>rechos. Los artículos<br />

son responsabilidad <strong>de</strong> los autores.<br />

Impreso y hecho en México<br />

Printed and ma<strong>de</strong> in Mexico<br />

Primera edición: 2008

ÍNDICE<br />

xii<br />

Presentación<br />

I. AIRE Y MEDICINA<br />

1 Where the air was impure<br />

Athanasios Diamandopoulos<br />

7 Flying doctors: The medicine reach the space<br />

Donatella Lippi<br />

11 L’air du corps dans l’air du temps: Le traite “<strong>de</strong> flatibus” <strong>de</strong> Joannes Fienus (1582)<br />

Jean-Pierre Tricot<br />

15 Air in Ancient Medicine. From Physiology and Pathology to Therapy and Physics<br />

Alain Touwai<strong>de</strong><br />

19 Creatures of the air<br />

David Wright<br />

27 Ehécatl as a wind god, illness producer in the Prehispanic Mexico<br />

María Blanca Ramos <strong>de</strong> Viesca, Carlos Viesca<br />

33 Air as a cause of illness in Mexican Traditional Medicine (XVIth to XXth centuries)<br />

Carlos Viesca, María Blanca Ramos <strong>de</strong> Viesca, Carmen Macuil García<br />

39 Jean-Baptiste Van Helmont et les gaz<br />

Diana Gasparon<br />

43 Isolation as effective control of air-transmissible disease: Historical highlights<br />

Andrea A. Conti, Gian Franco Gensini<br />

47 Air and Water. German Alternative Medicine in the 19th century<br />

Klaus Bergdolt<br />

51 The contribution of the Cluj Faculty of Medicine in the field of Respiratory Diseases<br />

in the XX century<br />

Cristian Barsu, Marina Barsu<br />

v

vi<br />

Índice<br />

57 The presence of air bubbles in bodily excrements as a bad prognostic sigh according<br />

to Ancient Greek and Byzantine writings<br />

Konstantina Goula, Maria Gavana, Pavlos Goulas, Athanasios Diamandopoulos<br />

61 Pneumonia and fever in New Spain during the XVIII century<br />

Rolando Neri Vela<br />

63 L’aria nel Liber <strong>de</strong> Arte Me<strong>de</strong>ndi (1564) di Cristóbal <strong>de</strong> Vega (1510-1573)<br />

Justo Hernán<strong>de</strong>z<br />

67 Pneumatic Machines in Antiquity (Air as source of energy in the Treatise on Pneumatics<br />

of Heron of Alexandria)<br />

André-Julien Fabre<br />

71 Airs, vents et souffle vital dans la mé<strong>de</strong>cine ancienne<br />

Ana María Rosso<br />

79 Air pollution and Fumifugium<br />

Laura Musajo Somma, Alfredo Musajo Somma<br />

85 Adventure in Sardinian Public Health Propaganda: A Case Study in Anti-Malaria<br />

Motion Picture Filmmaking<br />

Marianne P. Fedunkiw<br />

91 Un air salubre ou toxique, vecteur <strong>de</strong> la guérison dans les sanctuaires guérisseurs<br />

du mon<strong>de</strong> gréco-romain<br />

Cécile Nissen<br />

101 L’attenzione <strong>de</strong>ll’igiene pubblica per le polveri sottili nell’ambiente di vita e di lavoro<br />

Ilaria Gorini, Renato Soma<br />

105 L’ossigeno e il neonato prematuro<br />

Luigi Cataldi<br />

113 Il “soffio vitale”: l’anima nella storia <strong>de</strong>ll’uomo, <strong>de</strong>lla <strong>medicina</strong>, <strong>de</strong>ll’arte<br />

Luigi Cataldi, Maria Giuseppina Gregorio<br />

121 Il gas impiegati in terapia: ossigeno, protossido d’azoto e anidri<strong>de</strong> carbonica - (Aspetti storici)<br />

Giuliano Battistini<br />

127 Carlo Forlanini e il pneumotorace artificiale: Un sottile velo tra patologia e terapia<br />

Francesco De Tommasi, Massimo Pandolfi<br />

131 History of an Airborne Disease, Tuberculosis in Turkey (19 th -20 th cc)<br />

Yesim Isil Ulman, Can Ulman<br />

135 Conduzione nervosa e <strong>de</strong>cremento. Il ruolo <strong>de</strong>lla camera a gas<br />

Germana Pareti

Índice<br />

vii<br />

141 La chimica pneumatica e la funzione respiratoria<br />

Marinella Zacchino, Maria Antonietta Salemme Haas, Alfredo Musajo Somma<br />

145 Su di una conferenza avente per tema “L’aria” tenuta a Rovigo dal dr. Francesco Ciotto<br />

negli anni sessanta <strong>de</strong>ll’ottocento<br />

Massimo Aliverti<br />

151 L’inquinamento atmosferico agli albori <strong>de</strong>lla Rivoluzione Industriale. I casi trattati a Firenze<br />

durante il Risorgimento Italiano dal prof. Carlo Morelli<br />

Roberto Diddi<br />

157 “La forza <strong>de</strong>l vapore concita il commercio e la quarantena il trattiene”. Contagionisti<br />

e anticontagionisti tra <strong>medicina</strong> e traffici navali nella prima metá <strong>de</strong>l XIX secolo in Europa<br />

Fabio Bertini<br />

171 L’aria carrotta: il concetto <strong>de</strong>l contagio e la difesa sanitaria nell’Impero asburgico tra XVIII<br />

e XIX secolo. I Regolamenti Sanitari e le Patenti Imperiali: le zone di contumacia marittime e<br />

terrestri, i lazzaretti di Trieste e i cordoni sanitari <strong>de</strong>l confine orientale<br />

Euro Ponte, Luigia Bacarini<br />

179 La Hipoxia: From the first historical documents to prevention and treatment<br />

Tatiana S. Sorokina<br />

II. NEUROLOGICAL SCIENCES AND ANATOMY<br />

193 Freud a Firenze<br />

Adolfo Pazzagli, Stefano Pallanti, Duccio Vanni<br />

197 Spinoza: dall’anatomo-fisiologia secentesca alle attuali neuroscienze<br />

Matteo Bertaiola<br />

211 Un profilo grafologico di Domenico Barduzzi<br />

Piero Ascanelli, Francesco Aulizio<br />

215 L’‘odore’ <strong>de</strong>ll’ospedale: l’apporto <strong>de</strong>lla ricerca anatomica alla trasformazione <strong>de</strong>ll’ospedale<br />

mo<strong>de</strong>rno. Il caso <strong>de</strong>l Santa Maria Nuova di Firenze<br />

Esther Diana<br />

225 Historical outline of the Museum of Pathological Anatomy in Florence<br />

Gabriella Nesi, Raffaella Santi, Gian Luigi Tad<strong>de</strong>i

PRESENTACIÓN<br />

Analecta Historico Medica representa un esfuerzo editorial emanado <strong>de</strong> la Societas<br />

Internationalis Historiae Medicinae y el Departamento <strong>de</strong> Historia y Filosofía <strong>de</strong> la<br />

Medicina <strong>de</strong> la Facultad <strong>de</strong> Medicina <strong>de</strong> la Universidad Nacional Autónoma <strong>de</strong> México<br />

(UNAM). Su fin es proveer <strong>de</strong> un medio <strong>de</strong> difusión <strong>de</strong> alto nivel académico a los<br />

trabajos sobre Historia <strong>de</strong> la Medicina presentados en las reuniones internacionales<br />

que son organizadas cada dos años bajo los auspicios <strong>de</strong> la Sociedad, en los años<br />

en los que no se lleva a cabo el Congreso Internacional <strong>de</strong> Historia <strong>de</strong> la Medicina.<br />

Por tal razón, este es el sexto número <strong>de</strong> Analecta, ya que se <strong>de</strong>cidió tomar como<br />

el primero al volumen <strong>de</strong> las Actas <strong>de</strong> la Reunión Internacional llevada a cabo en<br />

Lisboa en 2001. La edición <strong>de</strong> Analecta será bianual, lo que contempla el que haya<br />

un volumen que se publique durante el año en el que se realicen los Congresos<br />

Internacionales, el cual contenga estudios monográficos <strong>de</strong> mayor extensión que<br />

los <strong>de</strong>stinados a ser publicados en Vesalio, órgano oficial <strong>de</strong> la Sociedad, o cahiers<br />

producto <strong>de</strong> reuniones planeadas ex profeso o reuniendo trabajos refe rentes a un<br />

tema <strong>de</strong>terminado y solicitados por invitación a los autores.<br />

ix

PRESENTATION<br />

In principle this would be the Analecta Historico Medica fourth issue, but, curiously,<br />

is the sixth one because the Editorial Commitee <strong>de</strong>ci<strong>de</strong>d to take as the first one the<br />

volume containing the papers presented at the First International Meeting on the<br />

History of Medicine, held in Lisbon in 2001. Analecta Historico Medica represents a<br />

common effort by the Internationalis Societas Historiae Medicinae and the Faculty<br />

of Medicine of Universidad Nacional Autónoma <strong>de</strong> México (UNAM)’ Department of<br />

History and Philosophy of Medicine. The aim is to provi<strong>de</strong> the historico-medical<br />

community a means to publish, at a high aca<strong>de</strong>mic level, the selected papers presented<br />

in the International Meetings organized every two years, precisely in the<br />

years when the corresponding International Congress wouldn’t take place. Analecta<br />

will appear twice a year and it will publish, one year, the materials provenient from<br />

the International Meeting, and in the following year, monographic studies which<br />

extension ma<strong>de</strong> it incovenient to be inclu<strong>de</strong>d in Vesalius, the official organ of the<br />

ISHM, and some cahiers <strong>de</strong>rived from specially organized meetings or symposia, or<br />

monothematic little collections requested by invitation to the authors.

PRESENTATION<br />

Ce livre aurait dû constituer le sixième volume <strong>de</strong>s ‘Analecta Historico-Medica’,<br />

mais, curieusement, il s’agit en fait du cinquiéme volume, le comité éditorial ayant<br />

décidé <strong>de</strong> considérer comme premier celui contenant les communications faites<br />

lors <strong>de</strong> la Première Réunion Internationale d’Histoire <strong>de</strong> la Mé<strong>de</strong>cine organisée à<br />

Lisbonne en 2001.Les Analecta Historico-Medica sont le reflet d’un effort commun<br />

entre La Société Internationale d’Histoire <strong>de</strong> la Mé<strong>de</strong>cine et la Faculté <strong>de</strong> Mé<strong>de</strong>cine<br />

<strong>de</strong> l’Universidad Nacional Autónoma <strong>de</strong> México (UNAM), Département d’Histoire<br />

et <strong>de</strong> Philosophie <strong>de</strong> la Mé<strong>de</strong>cine. Le but est <strong>de</strong> saisir l’occasion <strong>de</strong> publier, à un<br />

niveau académique élévé, les travaux présentés lors <strong>de</strong>s Réunions Internationales<br />

qui ont lieu tous les <strong>de</strong>ux ans, et ceci précisément durant les années où n’ont pas<br />

lieu les Congrès Internationaux d’Histoire <strong>de</strong> la Mé<strong>de</strong>cine. Les ‘Analecta’ paraîtront<br />

<strong>de</strong>ux fois chaque an et publieront l’une année les communications <strong>de</strong> ces Réunions<br />

Internationales et l’autre année <strong>de</strong>s étu<strong>de</strong>s monographiques fouillées, dont la longueur<br />

ne permet pas la publication dans ‘Vesalius’, organe officiel <strong>de</strong> la Société,<br />

ainsi que certains cahiers provenant <strong>de</strong> réunions ou <strong>de</strong> symposiums organisés lors<br />

d’événements spéciaux ou ayant pour sujet un thème spécifique dont l’étu<strong>de</strong> sera<br />

sollicitée à certains auteurs spécialisés.<br />

xi

I. AIRE Y MEDICINA

WHERE THE AIR WAS IMPURE<br />

Athanasios Diamandopoulos<br />

Presi<strong>de</strong>nt ISHM, Patra, Greece<br />

I would like to thank the organizers for asking<br />

me to present my lecture on Medicine and<br />

Air, the main subject of this Meeting. However,<br />

as this is a vast theme, I will. concentrate on<br />

some forms of air pollution and their effects<br />

on humans. Thus, the meaning I am trying to<br />

pass is better <strong>de</strong>fined as:<br />

WHERE THE AIR WAS IMPURE<br />

I choose my subject because air is the main element<br />

which on the function of life is based and<br />

also because its importance occupied the medical<br />

thought since antiquity. From the Greek<br />

medical thought I recall the belief of the pre<br />

Socratic philosophers/physicists that the universe<br />

was consisting from four elements,<br />

namely water, fire, air and earth, that correspon<strong>de</strong>d<br />

to the four human dispositions, i.e.<br />

warm, cold, dry and humid and to the four elements<br />

of the human body namely, the blood,<br />

the yellow bile, the black bile and the phlegm.<br />

Different combinations of the above produced<br />

different body type and psychological profiles,<br />

as well caused different diseases. I will. not elaborate<br />

on the above as they constitute the base<br />

of any medico-historical text book and they are<br />

not exactly related to the current topic. However,<br />

we should notice that the above believes,<br />

although rather cru<strong>de</strong>, they still emphasize the<br />

vital role of air in establishing and supporting<br />

life and health. Hippocrates, the legendary<br />

Father of Medicine had <strong>de</strong>voted a particular<br />

chapter to it in his book “On airs, waters and<br />

locations”. In it he emphasizes the need of a<br />

very <strong>de</strong>tailed observation of the blowing winds<br />

in any town, as he supports the notion that their<br />

temperature, direction, humidity and strength<br />

produce different afflictions to the adults and<br />

even <strong>de</strong>fects to the embryo. The same notion<br />

was held later by Galen and through him it survived<br />

both in the Orthodox East, the Latin West<br />

and the Arabs.<br />

The role of the air as an agent of health or<br />

disease was elevated during the great epi<strong>de</strong>mics<br />

of the Middle Ages. As people realized that<br />

the disease was spreading around infected<br />

persons without even touching them, the i<strong>de</strong>a<br />

of a necessary medium to contaminate others<br />

was born. The role of infectious microorganisms<br />

was not realized, and the same was<br />

true for intermidiaries, like mise or mosquitos.<br />

Hence, the impure air was the culprit via which<br />

an unknown and unindtified poisonous agent,<br />

the miasma was transferred from person to<br />

1

2 Athanasios Diamandopoulos<br />

person. It followed that the medical personel<br />

that atten<strong>de</strong>d the diseases should protect itself<br />

form this agent, by purifying the dirty air.<br />

Toward these means special garments were<br />

invented with masks capable to hold away the<br />

miasma, while permitting the doctor to breath.<br />

Although this may look ridiculous now, we<br />

should not forget that some bacilli (the tuberculosis<br />

mycoplasma e.g.) do travel via the air, and<br />

as long as masks are concerned for keeping<br />

the impure air away. they persist till. our days,<br />

albeit for different kind of pollution.<br />

I will not elaborate further on the historical<br />

documentation of the awareness of the medical<br />

profession to the toxic gases in the atmosphere,<br />

as I want to proceed quickly into the main body<br />

of this lecture. I will. only mention that during<br />

the Enlightenment, society and then the governments<br />

became anxious with the air pollution<br />

and tried to control it. It was part of the<br />

more general panic of the educated classes<br />

with anything not absolutely clear. The higher<br />

bureucray of the Ministry of Health, mainly in<br />

France, became the avant gar<strong>de</strong> of the guardians<br />

of clear air. There is a treasure of <strong>de</strong>tails<br />

on that in an excellent book titled “The Foul<br />

and the Fragnant: Odour and the Social Imagination”<br />

by Alain Corbin. Changing country and<br />

century, the most well known event on the<br />

improvent of the urban air, was the “Clean Air<br />

Act” that was enacted in London in 1956. After<br />

consultation with the medical profession there,<br />

in or<strong>de</strong>r to prevent respiratory damages due<br />

to the burning of open coal fires. On the week<br />

beginning the 5 th December 1952 thousands of<br />

Londoners died in the worst air pollution disaster<br />

on record.<br />

Nobody realised what was happening until<br />

it was noticed that the un<strong>de</strong>rtakers were running<br />

out of coffins and the florists out of flowers.<br />

Only later it was realised that the number<br />

of <strong>de</strong>aths during the days of the smog was three<br />

or four times normal.<br />

The <strong>de</strong>aths which resulted from the smog<br />

can be attributed primarily to<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

children<br />

The accepted figure is that the London<br />

smog killed around 12000 people.<br />

We are coming now closer to the current<br />

topic, that is the relationship between lung cancer<br />

and impurities in the air. The subject is vast,<br />

and I will. present only a short fragment of a<br />

paper published five years ago from the Mayo<br />

Clinic which conclu<strong>de</strong>s that “A small proportion<br />

of lung cancers (15% in men and 5% in women)<br />

are related to occupational agents, often overlapping<br />

with smoking: asbestos, radiation, arsenic,<br />

chromates, nickel, chloromethyl ethers, mustard<br />

(poison war) gas, and coke oven emissions. The<br />

exact role of air pollution is uncertain”.<br />

I call for your attention to the participation<br />

of mustard gas, a war poison, and I will. conclu<strong>de</strong><br />

my speech elaborating with more <strong>de</strong>tails<br />

on the role of impurities in the air caused by<br />

chemical wars and seriously damaging the<br />

human/animal/plant health.<br />

Chemical wars employing gases stared long –<br />

long ago, contrary to the current belief that it<br />

was an exclusive 20 th and sadly 21 sth century<br />

phenomenon. While the study of chemicals and<br />

their military uses was wi<strong>de</strong>spread in China,<br />

the use of toxic materials has historically been<br />

viewed with mixed emotions and some disdain

Where the air was impure 3<br />

in the West. One of the earliest reactions to the<br />

use of chemical agents was from Rome. Struggling<br />

to <strong>de</strong>fend themselves from the Roman<br />

legions, Germanic tribes poisoned the wells of<br />

their enemies, with Roman jurists having been<br />

recor<strong>de</strong>d as <strong>de</strong>claring: “armis bella non venenis<br />

geri”, meaning “war is fought with weapons,<br />

not with poisons.”<br />

Before 1915 the use of poisonous chemicals<br />

in battle was typically the result of local initiative,<br />

and not the result of an active government<br />

chemical weapons program. There are many<br />

reports of the isolated use of chemical agents<br />

in individual battles or sieges, but there was no<br />

true tradition of their use outsi<strong>de</strong> of incendiaries<br />

and smoke. Despite this ten<strong>de</strong>ncy, there have<br />

been several attempts to initiate large-scale<br />

implementation of poison gas in several wars,<br />

but with the notable exception of World War<br />

I, the responsible authorities generally rejected<br />

the proposals for ethical reasons. For example,<br />

in 1854 Lyon Playfair, a British chemist,<br />

proposed using a cyani<strong>de</strong>-filled artillery shell<br />

against enemy ships during the Crimean War.<br />

The British Ordnance Department rejected the<br />

proposal as “as bad a mo<strong>de</strong> of warfare as poisoning<br />

the wells of the enemy”. Efforts were ma<strong>de</strong><br />

to eliminate the future use of poisonous gases,<br />

hence: In August 27, 1874: The Brussels Declaration<br />

Concerning the Laws and Customs<br />

of War is signed, specifically forbidding the<br />

“employment of poison or poisoned weapons.”<br />

And later, on September 4, 1900: The Hague<br />

Conference, inclu<strong>de</strong>d a <strong>de</strong>claration banning<br />

the “use of projectiles the object of which is the<br />

diffusion of asphyxiating or <strong>de</strong>leterious gases”.<br />

In spite of that, the most startling example of<br />

chemical war was The Great World War 1. Hundreds<br />

of thousands of soldiers were killed then<br />

by gases. Instead of <strong>de</strong>scribing my self the horror<br />

of the scenes, I am presenting only a few<br />

fragments, as told by the eye witnesses: The<br />

British Comman<strong>de</strong>r-in-Chief and a great warwizard<br />

like Lord Armstrong, who called the<br />

gas-cloud “the most <strong>de</strong>vilish <strong>de</strong>vice ever invented<br />

by human ingenuity.” “I much regret,” wrote Sir<br />

John French, “that during the period un<strong>de</strong>r report<br />

(the second Battle of Ypres) the enemy has shown<br />

a cynical and barbarous disregard of- the wellknown<br />

usages of civilised war, and a flagrant <strong>de</strong>fiance<br />

of the Hague Convention.” The yellow <strong>de</strong>ath<br />

rose like a marsh-mist, and rolled in seven-foot<br />

banks upon our lines. “From above,” says a German<br />

airman, “ it looked as if the very soil itself<br />

were walking, after months of immobility. On<br />

and on swept the soft mysterious terror. Rising<br />

ó quickening ó pausing, as it were to peep<br />

into enemy trenches, then sinking like a living<br />

thing. Shrieks of terror came up to me; then I<br />

saw a panic flight. We pursued them even to<br />

the second and third positions.” Franco-British<br />

science soon came to the rescue. What was<br />

the stuff? “Liquid chlorine,” replied Sir James<br />

Dewar (Ill. 4); “Bromine,” said Dr. F. A. Mason<br />

of South Kensington; “Carbon-monoxi<strong>de</strong>,” was<br />

Dr. Crocker’s guess; and “Phosgene,” that of Dr.<br />

W. J. Pope, Professor of Chemistry at Cambridge.<br />

Anti gas masks were dispensed to all<br />

soldiers who used them in the battles, without<br />

avoiding always the burns from chlorine<br />

or mustard air (Ill. 8), another wi<strong>de</strong>ly<br />

used then chemical weapon. And war-wizard<br />

Turpin set to work with liquid ammonia<br />

as an antidote to those fearsome fumes. Antigas<br />

bombs were soon thrown into the rolling<br />

banks of <strong>de</strong>ath. Grena<strong>de</strong>s full of liquid oxygen<br />

too. Bisulphi<strong>de</strong> of sodium was also sprayed<br />

on the advancing cloud, according to the formula<br />

of M. Edmund Perrier, Director of the<br />

French Museum of Natural History. Then down<br />

at Châlons-sur-Marne “weeping”-shells ma<strong>de</strong><br />

their appearance. When they burst they set the

4 Athanasios Diamandopoulos<br />

eyes streaming with tears and ma<strong>de</strong> shooting<br />

an utterly hopeless task. “But the fumol fumes of<br />

these have no <strong>de</strong>adly effect. They merely put the<br />

marksman out of action for the time. He’s soon<br />

a prisoner in his own trench with the foe “wiping<br />

his eye” in triumph. Here at home Sir Hiram<br />

Maxim produced a petrol-bomb to explo<strong>de</strong> in the<br />

gas-cloud and lift it harmlessly over our men’s<br />

heads.” Hence the Allies were careful to use<br />

“humanitarian” gases against the Germans. It<br />

doesn’t look that they had the same sensitivities<br />

in the theoretical case to use them against<br />

non Europeans: “I am strongly in favour of using<br />

poisoned gas against uncivilized tribes. The moral<br />

effect should be good... and it would spread a<br />

live ly terror...” (Winston Churchill, commenting<br />

on the British use of poison gas against the Iraqis<br />

after the First World War). However, gases<br />

were not eventually used against the Iraqis.<br />

In the horrible aftermath of the World<br />

War 1, more efforts were ma<strong>de</strong> to prohibid war<br />

gases. Thus, on February 6, 1922: After World<br />

War I, the Washington Arms Conference Treaty<br />

prohibited the use of asphyxiating, poisonous or<br />

other gases. It was signed by the United States,<br />

Britain, Japan, France, and Italy, but France<br />

objected to other provisions in the treaty and it<br />

never went into effect. On September 7, 1929:<br />

The Geneva Protocol enters into force, prohibiting<br />

the use of poison gas and bacteriological<br />

methods of warfare. As of 2004, there are 132<br />

signatory nations. In spite of the above more<br />

sophisticated war gases were invented and also<br />

used during world war 2. We see in the next ILL.<br />

British protective masks for nurses, animals and<br />

house-wives!<br />

The efforts for eliminating war gases continued<br />

after the WW2. In May 1991: Presi<strong>de</strong>nt<br />

George H.W. Bush (senior) unilaterally commits<br />

the United States to <strong>de</strong>stroying all chemical<br />

weapons and to <strong>de</strong>nounce the right to chemical<br />

weapon retaliation. In April 29, 1997: The<br />

Chemical Weapons Convention enters into<br />

force, augmenting the Geneva Protocol of<br />

1925 by outlawing the production, stockpiling<br />

and use of chemical weapons. The U.S. Congress<br />

has since passed legislation requiring the<br />

<strong>de</strong>struction of the entire stockpile by December<br />

31, 2004. Official U.S. policy is to support the<br />

Chemical Weapons Convention as a means to<br />

achieve a global ban on this class of weapons<br />

and to halt their proliferation.<br />

But theory is set apart from practice.<br />

About 70 different chemicals have been used or<br />

stockpiled as Chemical Weapons (CW) agents<br />

during the 20th century, by various countries.<br />

We can see just two examples of their containers.<br />

Again special uniforms were created to<br />

protect the military personel.<br />

This indifference towards the world’s<br />

ethical co<strong>de</strong> unavoidably led to more horrors.<br />

A new culprit was invented and extensively<br />

used, causing harmful effects and<br />

possibly lung cancer. I was the <strong>de</strong>pleted uranium,<br />

which was called “The Trojan Horse of<br />

Nuclear War”. Since 1991, the United States<br />

has staged four wars using <strong>de</strong>pleted uranium<br />

weaponry, illegal un<strong>de</strong>r all international treaties,<br />

conventions and agreements, as well as<br />

un<strong>de</strong>r the US military law ... Described as the<br />

Trojan Horse of nuclear war, <strong>de</strong>pleted uranium<br />

is the weapon that keeps killing. The half-life<br />

of Uranium-238 is 4.5 billion years, the age of<br />

the earth. And, as Uranium-238 <strong>de</strong>cays into<br />

daughter radioactive products, in four steps<br />

before turning into lead, it continues to release<br />

more radiation at each step. There is no way to<br />

turn it off, and there is no way to clean it up.<br />

It meets the US Government’s own <strong>de</strong>finition<br />

of Weapons of Mass Destruction. Dr. Rosalie

Where the air was impure 5<br />

Bertell, one of the 46 international radiation<br />

expert authors of the European Committee<br />

on Radiation Risk report, <strong>de</strong>scribes it as:<br />

“The concept of species annihilation means<br />

a relatively swift, <strong>de</strong>liberately induced end to<br />

history, culture, science, biological reproduction<br />

and memory. It is the ultimate human<br />

rejection of the gift of life, an act which<br />

requires a new word to <strong>de</strong>scribe it: omnici<strong>de</strong>.”<br />

Depleted uranium weapons were first<br />

given by the US to Israel for use un<strong>de</strong>r US supervision<br />

in the 1973 Sinai war against the Arabs.<br />

Since then the US has tested, manufactured,<br />

and sold <strong>de</strong>pleted uranium weapons systems<br />

to 29 countries. An international taboo prevented<br />

their use until 1991, when the US broke<br />

the taboo and used them for the first time,<br />

on the battlefields of Iraq Iran and Kuwait,<br />

causing severe casualties amongst the civilians,<br />

and a lot of pri<strong>de</strong> by the Iraqis.<br />

Consi<strong>de</strong>ring that the US has admitted using<br />

34 tons of <strong>de</strong>pleted uranium from bullets and<br />

cannon shells in Yugoslavia, and the fact that<br />

35,000 NATO bombing missions occurred there<br />

in 1999, potentially the amount of <strong>de</strong>pleted<br />

uranium contaminating Yugoslavia and transboundary<br />

drift into surrounding countries is<br />

staggering. Although restricted to battlefields<br />

in Iraq and Kuwait, the 1991 Gulf War was one<br />

of the most toxic and environmentally <strong>de</strong>vastating<br />

wars in world history. In 1990, the United<br />

Kingdom Atomic Energy Authority (UKAEA)<br />

wrote a report warning about the potential<br />

health and environmental catastrophe from<br />

the use of <strong>de</strong>pleted uranium weapons. The<br />

health effects had been known for a long time.<br />

The report sent to the UK government warned<br />

“In their estimation, if 50 tonnes of residual DU<br />

dust remained in the region there could be half a<br />

million extra cancers by the end of the century<br />

[2000]”. Estimations like this didn’t prevent<br />

Presi<strong>de</strong>nt George W. Bush (senior) to claim on<br />

the official White House website: “During the<br />

Gulf War, coalition forces used armor-piercing<br />

ammunition ma<strong>de</strong> from <strong>de</strong>pleted uranium, which<br />

is i<strong>de</strong>al for the purpose because of its great<br />

<strong>de</strong>nsity ...But scientists working for the World<br />

Health Organization, the UN Environmental<br />

Programme, and the European Union could find<br />

no health effects linked to exposure to <strong>de</strong>pleted<br />

uranium...”<br />

However, we shouldn’t rush to accuse the<br />

USA as the only criminal providing <strong>de</strong>pleted<br />

Uranium to the Iraqis during Sadam Housein’s<br />

regime. Iraq’s army was primarily armed<br />

with weaponry it had purchased from several<br />

countries.<br />

the Soviet Union and its satellites in the<br />

preceding <strong>de</strong>ca<strong>de</strong>. During the war, it purchased<br />

billions of dollars worth of advanced<br />

equipment from the Soviets and the French,<br />

as well as from the People’s Republic of China,<br />

Egypt, Germany, and other sources (including<br />

Europe and facilities for making and/or enhancing<br />

chemical weapons). Germany along with<br />

other Western countries (among them United<br />

Kingdom, France, Spain Italy and the United<br />

States) provi<strong>de</strong>d Iraq with biological and chemical<br />

weapons technology and the precursors to<br />

nuclear capabilities. Much of Iraq’s financial<br />

backing came from other Arab states, notably<br />

oil-rich Kuwait and Saudi Arabia. Iran’s<br />

foreign supporters inclu<strong>de</strong>d Syria and Libya,<br />

through which it obtained Scuds. It purchased<br />

weaponry from North Korea and the People’s<br />

Republic of China, notably the Silkworm antiship<br />

missile. Iran acquired weapons and parts<br />

for its Shah-era U.S. systems through covert<br />

arms transactions from officials in the Reagan

6 Athanasios Diamandopoulos<br />

Administration, first indirectly (possibly through<br />

Israel) and then directly. It was hoped Iran would,<br />

in exchange, persua<strong>de</strong> several radical groups to<br />

release Western hostages, though this did not<br />

result; proceeds from the sale were diverted to<br />

the Nicaraguan Contras in what became known<br />

as the Iran-Contra Affair.<br />

According to an October 2004 Dispatch<br />

from the Italian Military Health Observatory,<br />

a total of 109 Italian soldiers have died thus<br />

far due to exposure to <strong>de</strong>pleted uranium. A<br />

spokesman at the Military Health Observatory,<br />

Domenico Leggiero, states “The total<br />

of 109 casualties exceeds the total number of<br />

persons dying as a consequence of road acci<strong>de</strong>nts.<br />

Anyone <strong>de</strong>nying the significance of such<br />

data is purely acting out of ill. faith, and the<br />

truth is that our soldiers are dying out there<br />

due to a lack of a<strong>de</strong>quate protection against<br />

<strong>de</strong>pleted uranium”. There were only 3,000 Italian<br />

soldiers sent to Iraq, and they were there<br />

for a short time. The number of 109 represents<br />

about 3.6% of the total. If the same per centage<br />

of Iraqis get a similar exposure, that would<br />

amount to 936,000. As Iraqis are permanently<br />

living in the same contaminated environment,<br />

their percentage will. be higher.<br />

I am afraid I didn’t manage to present a<br />

light topic for our Opening session, something<br />

like classical music or a folk dance. Still. the<br />

Editorials of The Lancet and The New York Journal<br />

of Medicine are much more austere on this<br />

issue. If a moral conclussion could be drown of<br />

this presentation, it may be that we have to be<br />

restrained in our use of weaponry. Who knows<br />

who will. be harmed by them. As William<br />

Shakespeare has written: “Heat not a furnace<br />

for your foe so hot that it do singe yourself”. And<br />

let us not forget that there are medical doctors<br />

working on every stage of their creation.

FLYING DOCTORS: THE MEDICINE REACH THE SPACE<br />

Donatella Lippi<br />

University of Florence, Italy<br />

After the theme of Water in 2005, the main<br />

topic of the present meeting is another fundamental<br />

element of the environment, Air, which<br />

has been fascinating philosophers, scientists<br />

and theologists for centuries.<br />

Air is a musical concept, too and it has<br />

been paradoxically painted as wind or in various<br />

personifications in many masterpieces<br />

throughout the world in every age.<br />

I have chosen a particular point of view: in<br />

the Hippocratic theory of medicine, air was consi<strong>de</strong>red<br />

a fundamental element of the environment<br />

to ensure a good quality of life: at the same<br />

time, however, Hippocrates tells us that the Athenians,<br />

believing that the plague was caused by<br />

impure air, fought it by lighting huge bonfires.<br />

In the light of present knowledge, we may<br />

be tempted to laugh at the old beliefs concerning<br />

the dangers lurking in air, but on the other<br />

hand we know that many diseases are spread<br />

through air and mo<strong>de</strong>rn means of transport<br />

can make the diffusion of dangerous pathologies<br />

easier.<br />

It is the case of AIDS, which travelled on a<br />

jumbo jet and reached other continents terribly<br />

quickly.<br />

The conquest of space and air, through the<br />

invention of the airplane has permitted the use<br />

of air medical services. They have become an<br />

essential component of the health care system<br />

in those countries, where very long distances,<br />

compromise the performance of a medical<br />

intervention or its outcome.<br />

Air medical critical care transport saves<br />

lives and reduces the cost of health care, minimizing<br />

the time the critically injured and ill<br />

spend outsi<strong>de</strong> the hospital, bringing more medical<br />

capabilities to the patient and getting the<br />

patient to the right specialty care as soon as<br />

possible.<br />

This has become feasible since medicine,<br />

aviation and radio have been combined to<br />

bring health care to the people who live, work<br />

and travel in isolated areas: it is not by chance<br />

that we begin this historical review starting<br />

from our antipo<strong>de</strong>s, Australia.<br />

As a matter of fact, the organization of Flying<br />

Doctors was first established here in 1928<br />

and <strong>de</strong>veloped on a national basis in the 1930s.<br />

The story of the Flying Doctor Service is<br />

strictly linked with its foun<strong>de</strong>r, the Very Reverend<br />

John Flynn.<br />

The Reverend John Flynn was born at<br />

Moliagul, Victoria, on 25 November 1880. He<br />

completed his training for the Presbyterian<br />

ministry, and in 1911 was appointed to the<br />

7

8 Donatella Lippi<br />

Smith of Dunesk Mission in the North Flin<strong>de</strong>rs<br />

Ranges of South Australia.<br />

When Flynn examined a map of Australia,<br />

he saw that not only the Northern Territory, but<br />

a great <strong>de</strong>al of Queensland, Western Australia,<br />

New South Wales and South Australia —almost<br />

two-thirds of the continent— were virtually<br />

without a minister, a doctor, or even a nurse.<br />

Flynn was undaunted by the enormity of the<br />

task ahead.<br />

In 1912 Flynn was commissioned to un<strong>de</strong>rtake<br />

a survey of the needs of both the Aboriginal<br />

people and white settlers in the Northern<br />

Territory. His <strong>de</strong>tailed reports resulted in the<br />

creation by the Presbyterian Church of its Australian<br />

Inland Mission (AIM), of which Flynn<br />

was appointed Superinten<strong>de</strong>nt. The Mission,<br />

which commenced its operation with one nursing<br />

hostel, a nursing sister and a padre, had by<br />

1926, un<strong>de</strong>r Flynn’s lea<strong>de</strong>rship, become a network<br />

of ten strategically placed nursing hostels<br />

operating closely with patrol padres.<br />

When Flynn began his missionary work,<br />

only two doctors served an incredibly wi<strong>de</strong> area:<br />

he started establishing bush hospitals and hostels<br />

in isolated areas, but even if they provi<strong>de</strong>d<br />

an important service, their efforts were only<br />

scratching the surface of a very <strong>de</strong>ep problem.<br />

The lack of medical treatment due to the<br />

problems of distance and communication<br />

caused people to die.<br />

Keenly aware of the isolation of the people<br />

of inland Australia, between 1913 and 1927<br />

Flynn used his magazine The Inlan<strong>de</strong>r as a vehicle<br />

to elicit financial support, to publicize the<br />

Mission’s achievements and to make known his<br />

plans for the future. He believed that a ‘mantle<br />

of safety’ could be created for the isolated communities<br />

of Northern Australia only with the<br />

establishment of an aerial medical service and<br />

the introduction of radio communications.<br />

When the aeroplane proved itself as a reliable<br />

mean of transport and radio was beginning<br />

to put in touch people living thousands of<br />

miles far away from each other, Flynn instinctively<br />

knew the potential of science and techniques<br />

and, relying on the help of Clifford Peel,<br />

a young medical stu<strong>de</strong>nt, published the project<br />

in his Inlan<strong>de</strong>r magazine.<br />

Flynn realised, however, that to operate<br />

successfully the fledgling aerial medical service<br />

had to become part of a national operation<br />

with access to greater resources. To this end,<br />

he maintained constant contact with Members<br />

of Parliament and argued persuasively to gain<br />

the approval of the Presbyterian Church for a<br />

wi<strong>de</strong>r co-operative venture.<br />

In 1928, the Australian Inland Mission had<br />

sufficient money to establish a flying doctor<br />

scheme and on May 1928, the Aerial Medical<br />

Service was established at Cloncurry.<br />

It was an experiment but its success<br />

increased and surbibed the Great Depression<br />

of 1929.<br />

By 1932 the AIM had a network of ten hospitals<br />

and continued to grow over the next few<br />

years.<br />

In 1934, the Australian Aerial Medical Service,<br />

as it was then known, was established.<br />

(The name was changed in 1942 to the Flying<br />

Doctor Service of Australia, and the <strong>de</strong>signation<br />

‘Royal’ was ad<strong>de</strong>d in 1955.)<br />

In 1934 the organization was so big that<br />

the Presbyterian Church han<strong>de</strong>d the service<br />

over to the Australian Aerial Medical Service<br />

and in 1942 the service receive the present<br />

name , which was enabled by the Royal prefix<br />

in 1955.<br />

Public appeals for donations were repeatedly<br />

launched because the Government aid was<br />

not enough and even today the service continues<br />

to rely on private initiatives.

Flying doctors: The medicine reach the space 9<br />

The number of bases and the area covered<br />

by the service has gradually increased and the<br />

service has changed.<br />

First the responsabilities of the FD were to<br />

fly to urgent cases, ren<strong>de</strong>r first aid and transport<br />

the patient to hospital, giving advice by<br />

radio and providing also medical treatment to<br />

areas without doctors, too.<br />

Today, the objectives are the same, but<br />

they have been empowered thanks to telephones<br />

and vi<strong>de</strong>o-conferencing technology.<br />

Its services inclu<strong>de</strong>:<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

satellite-phones and portable vi<strong>de</strong>o conferencing<br />

units.<br />

<br />

regular clinical visits to remote areas (usually<br />

a circuit visiting several communities<br />

and/or stations)<br />

<br />

for rural and remote doctors across Australia<br />

<br />

The service also utilizes not just aircraft<br />

but also four-wheel drives and other utility land<br />

vehicles to aid in transportation and communications.<br />

Another very important task <strong>de</strong>veloped by<br />

Flyng Doctors is the School of the Air, a correspon<strong>de</strong>nce<br />

school catering for the primary<br />

and early secondary education of children in<br />

remote Australia.<br />

Stu<strong>de</strong>nts, living in isolated areas, before<br />

Internet services, received their course materials<br />

and returned them using the Royal Flying<br />

Doctors Service.<br />

The example of FD was followed in other<br />

parts of the world; in the 1980s the Association<br />

of Air Medical Services was foun<strong>de</strong>d and in<br />

1993 the Air Medical Journal gathered the legacy<br />

of Hospital Aviation and Journal of Aeromedical<br />

Healthcare.<br />

To conclu<strong>de</strong>, I would like to stress that telemedicine<br />

and telehealth are not an invention<br />

of the latest days, but an old practice However<br />

new trends in long distance care still represent<br />

a challenge in medicine.<br />

The distance between health centers and<br />

sick people has always been a great problem, but<br />

long physicial distances can be reduced by technology.<br />

Physician and patient, however, can be<br />

far apart, even if physically close to each other.<br />

Measuring patient-physician cultural distance<br />

might someday have clinical applicability.<br />

Currently, cultural competence education<br />

is generally tailored to improve health professionals’<br />

ability to care for all patients, but<br />

particularly for those from racial and ethnic<br />

minority groups.<br />

It’s our duty to address our care in this<br />

direction.

L’AIR DU CORPS DANS L’AIR DU TEMPS: LE TRAITE<br />

“DE FLATIBUS” DE JOANNES FIENUS (1582)<br />

Prof. Dr Jean-Pierre Tricot<br />

Societas Belgica Historiae Medicinae<br />

Jan Palfijn Foundation, Gent<br />

LA RENAISSANCE DE LA MÉDECINE<br />

La renaissance médicale qui se développe en<br />

Europe Occi<strong>de</strong>ntale durant le 16 e siècle est<br />

caractérisée par d’importants efforts individuels<br />

fournis par <strong>de</strong>s mé<strong>de</strong>cins qui mettent<br />

les principes <strong>de</strong> raison et <strong>de</strong> libre examen au<strong>de</strong>ssus<br />

<strong>de</strong> ceux dictés par d’anciennes lois et<br />

par <strong>de</strong>s dogmes réputés immuables. Les universités<br />

ne suivent pas ce nouveau courant et,<br />

durant la secon<strong>de</strong> moitié du 16 e siècle, celle<br />

<strong>de</strong> Louvain connait un déclin très sensible. En<br />

effet les idées établies et l’autorité <strong>de</strong>s anciens<br />

maîtres ne peuvent y être contestées: <strong>de</strong>s faits<br />

et observations à l’encontre <strong>de</strong> ces principes<br />

sacrés sont jugés inacceptables par le corps<br />

professoral <strong>de</strong> l’époque.<br />

Le développement <strong>de</strong> l’imprimerie permet<br />

heureusement la propagation <strong>de</strong>s idées nouvelles.<br />

L’Officine Plantinienne d’Anvers publie ainsi<br />

<strong>de</strong> nombreux ouvrages médicaux tels que <strong>de</strong>s<br />

copies <strong>de</strong> la ‘Fabrica’ d’André Vésale par Grévin<br />

ou Valver<strong>de</strong> ou encore le magistral ‘Cruy<strong>de</strong>-<br />

Boeck’ (Livre <strong>de</strong>s Plantes) du malinois Rembert<br />

Dodoens. Mais d’autres ouvrages médicaux<br />

sont également édités dans une <strong>de</strong>s nombreuses<br />

imprimeries anversoises et certains d’entre<br />

eux connaissent un succès immense. Parmi<br />

ceux-ci le traité ‘De flatibus’ rédigé par Fienus,<br />

mé<strong>de</strong>cin méconnu, à tort, encore aujourd’hui.<br />

BIOGRAPHIE DE JAN FEYENS<br />

Jan Fyens, surnommé en latin Joannes Fienus<br />

nait probablement vers 1537 à Turnhout, au<br />

nord d’Anvers. Il est élevé parmi les enfants <strong>de</strong><br />

choir <strong>de</strong> la cathédrale <strong>de</strong> Bois-le-Duc, autre ville<br />

brabançonne. Il y acquiert <strong>de</strong> bonnes no-tions<br />

musicales mais ne se sent pas la vocation d’un<br />

musicien. Il entreprend alors <strong>de</strong>s étu<strong>de</strong>s <strong>de</strong><br />

mé<strong>de</strong>cine à l’Université <strong>de</strong> Louvain où il s’inscrit<br />

à la pédagogie, ‘Le Cochon’ parmi les ‘divites’<br />

(= <strong>de</strong> parents aisés). Il s’installe ensuite à<br />

Anvers où il est nommé mé<strong>de</strong>cin pensionnaire<br />

<strong>de</strong> la ville et exerce sa profession avec succès.<br />

Après le début du siège <strong>de</strong> la ville par les espagnols<br />

sous le comman<strong>de</strong>ment <strong>de</strong> Farnèse, duc<br />

<strong>de</strong> Parme, Fienus se retire en 1584 à Dordrecht,<br />

dans les Pays-Bas septentrionaux, où il meurtun<br />

an plus tard, le 2 août, quelques jours avant<br />

la capitulation d’Anvers <strong>de</strong>vant l’envahisseur<br />

espagnol le 9 août 1585.<br />

Son fils, Thomas Fienus (1567-1631) reprend<br />

le flambeau et <strong>de</strong>vient professeur primarius <strong>de</strong><br />

mé<strong>de</strong>cine à l’Alma Mater louvaniste. Thomas<br />

11

12 Jean-Pierre Tricot<br />

est surtout connu pour son ouvrage ‘De cauteriis’<br />

publié en 1598. Grace à lui l’université<br />

<strong>de</strong> Louvain conna”trait un nouvel épanouissement<br />

après avoir été proche <strong>de</strong> sa ruine quelques<br />

années auparavant. A trois reprises il y fut<br />

honoré du rectorat.<br />

LE ‘TRAITÉ DES VENTS’ DE FIENUS ET<br />

SES SOURCES<br />

En 1582, Joannes Fienus avait publié à Anvers<br />

chez Jan Van Ghelen et Henricus, un livre fort<br />

original sur les flatuosités: ‘Ionnis Fienj Andoverpianj<br />

DE FLATIBUS HUMANUM corpus molestantibus,<br />

commentarius novus ac singularis.<br />

In quo Flatuum Natura, Causae et Symptomata<br />

<strong>de</strong>scribuntur, eorumque remedia Facili et expedita<br />

methodo indicantur’. Il s’agit par ailleurs du<br />

seul écrit qui nous reste <strong>de</strong> lui et dont le titre<br />

complet est un parfait reflet <strong>de</strong> son contenu.<br />

Bien que Fienus affirme qu’Hippocrate<br />

ait écrit plus savamment qu’utilement sur la<br />

matière, il est regrettable qu’il ait lui-même<br />

adhéré fortement aux idées scolastiques en<br />

vogue dans son temps, faisant ainsi fréquemment<br />

référence aux auteurs anciens et en particulier<br />

à Hippocrate et à Galien.<br />

Dans son ‘Traité <strong>de</strong>s Vents’ Hippocrate<br />

explique que selon lui le corps a besoin <strong>de</strong><br />

nourriture, <strong>de</strong> boisson ainsi que <strong>de</strong> souffle,<br />

‘vent’ à l’intérieur du corps, ‘air’ à l’extérieur.<br />

Il explique commet l’air, mélangé avec la nourriture<br />

avalée peut être à l’origine <strong>de</strong> plusieurs<br />

maladies telles que pestilences, fievres, congestion,<br />

hémophtisie, apoplexie et épilepsie. Il en<br />

conclut que les vents sont la cause principale<br />

<strong>de</strong> toutes les maladies, toutes les autres causes<br />

leur étant subordonnées.<br />

D’autre part Fienus adopte encore toujours<br />

la physiologie <strong>de</strong> Galien, qui attribue toutes les<br />

activités <strong>de</strong> la vie à trois espèces d’esprit classée<br />

selon leur <strong>de</strong>nsité. Les premiers, fabriqués<br />

dans le foie, sont véhiculés dans les veines.<br />

Les seconds, nés dans le ventricule gauche<br />

du cúur, sont distribués par les artères. Les<br />

troisièmes, encore plus subtils, élaborés dans<br />

le cerveau, circulent dans les nerfs. Et enfin la<br />

quatriemè espèce d’esprit gras et vaporeux,<br />

esprit venteux ou vent, en tout point semblable<br />

au vent du mon<strong>de</strong> extérieur.<br />

Se référant à Platon et à Aristote Fienus<br />

distingue en outre trois esprits supérieurs: celui<br />

du Dieu vivant, celui <strong>de</strong> route la nature et un<br />

esprit propre à l’ âme<br />

Fienus déclare que dans son écrit il va droit<br />

à la pratique sans s’arrêter à <strong>de</strong> vaines spéculations<br />

et qu’il se fon<strong>de</strong> sur une longue expérience<br />

personnelle ainsi que sur l’enseignement<br />

<strong>de</strong> Jean Fernel (1494-1550). Il mentionne que<br />

ses idées sont partagées par <strong>de</strong>ux <strong>de</strong> ses amis:<br />

Jean Lange (1485-1565), mé<strong>de</strong>cin <strong>de</strong> quatre<br />

électeurs du Palatinat, et Reignier Solenan<strong>de</strong>r<br />

(1521-1596), praticien à Düsseldorf. Deux professeurs<br />

belges avaient déjà aussi écrit sur les<br />

vents : en 1542 Hieronymus Thriverius à Louvain<br />

et en 1578 Petrus Memmius à Rostock.<br />

Le succès du livre est considérable. On<br />

dénombre plusieurs éditions en latin entre 1582<br />

et 1664 à Anvers, aux Pays-Bas et en Allemagne<br />

ainsi que <strong>de</strong>s traductions en néerlandais,<br />

en anglais et en allemand <strong>de</strong> 1668 à 1759.<br />

Curieusement aucune traduction française ne<br />

nous est connue.<br />

Un tel engouement est du à la gran<strong>de</strong> originalité<br />

<strong>de</strong> l’ouvrage dans lequel l’auteur s’attache<br />

à étudier une matière qui jusqu’alors avait<br />

été complètement négligée quoique les plaintes<br />

provoquées par le gonflement <strong>de</strong> l’estomac et<br />

<strong>de</strong>s intestins étaient fort courantes à l’époque.<br />

Le livre <strong>de</strong> Fienus est divisé en 28 chapitres.<br />

Les premiers sont consacrés à l’esprit <strong>de</strong>s

L’air du corps dans l’air du temps 13<br />

flatulences, à leur analogie avec les vents, à<br />

leur définition, où et pourquoi elles sont générées<br />

et à leurs différentes formes. La secon<strong>de</strong><br />

partie traite <strong>de</strong>s maladies à l’origine <strong>de</strong>s flatulences,<br />

<strong>de</strong> leurs causes, signes et symptômes<br />

et <strong>de</strong> leur pronostic. Dans les <strong>de</strong>rniers chapitres,<br />

différents traitements sont proposés,<br />

d’une part <strong>de</strong>s traitements généraux et d’autre<br />

part <strong>de</strong>s traitements spécifiques à certaines<br />

maladies.<br />

D’après Fienus les flatuosités n’appartiennent<br />

ni aux esprits animaux, ni aux esprits naturels,<br />

elles sont provoquées par les maladies, tout<br />

comme les vents <strong>de</strong> l’atmosphère le sont par les<br />

nuages et les vapeurs. Ces flatuosités, dont il<br />

existe plusieurs sortes, consistent donc en une<br />

multitu<strong>de</strong> d’esprits tumultueux engendrés par<br />

les aliments et les boissons, par une humeur<br />

pituiteuse ou mélancolique ou par une diminution<br />

<strong>de</strong> la chaleur naturelle. Ainsi, <strong>de</strong>s aliments<br />

froids ou crus ou pris en trop gran<strong>de</strong> quantité,<br />

certains fruits, certains légumes et <strong>de</strong>s substances<br />

indigestes produisent <strong>de</strong>s vents en diminuant<br />

la chaleur innée et causant obstruction<br />

et putréfaction. Les flatuosités peuvent aussi<br />

trouver leur origine dans la matière visqueuse<br />

ou aci<strong>de</strong> qui se trouve dans les boyaux. Fienus<br />

fait également état d’une influence climatique<br />

en soutenant que les flatulences seraient moins<br />

fréquentes dans les régions chau<strong>de</strong>s. Ce sont<br />

surtout les personnes flegmatiques, les personnes<br />

délicates et les femmes, dont les viscères<br />

sont affaiblies et susceptibles d’expansion, qui<br />

sont sujettes à ce mal.<br />

Bien qu’il tente d’étudier en quels endroits<br />

du corps les gaz se forment (le mot ‘gaz’ n’existait<br />

pas encore et ne sera introduit qu’au début<br />

du 17 e siècle par Jean-Baptiste Van Helmont),<br />

Fienus ne mentionne nulle part la véritable<br />

cause <strong>de</strong> ces maux, c’est-à-dire l’état morbi<strong>de</strong><br />

<strong>de</strong>s intestins mêmes.<br />

Il décrit également les douleurs et les<br />

bruits différents que ces flatulences provoquent<br />

d’après leur lieu d’origine. Les signes<br />

précurseurs sont <strong>de</strong>s bruits intestinaux, <strong>de</strong>s<br />

gargouillements, accompagnés d’une sensation<br />

<strong>de</strong> tension abdominale, <strong>de</strong> hoquet et <strong>de</strong> nausées.<br />

Ces symptômes diminuent ou disparaissent<br />

par l’éruption <strong>de</strong>s flatulences.<br />

Ces flatulences peuvent distendre et pénétrer<br />

plusieurs organes. Ainsi par exemple<br />

s’insinuent-elles par <strong>de</strong>s voies occultes entre les<br />

méninges, dans le scrotum, la plèvre, le périoste<br />

et jusque dans les racines <strong>de</strong>s <strong>de</strong>nts provoquant,<br />

en distendant nerfs et tissus, <strong>de</strong>s symptômes<br />

fort variés tels que <strong>de</strong>s maux <strong>de</strong> tête, <strong>de</strong>s palpitations<br />

cardiaques, <strong>de</strong>s douleurs dorsales, <strong>de</strong>s<br />

odontalgies, <strong>de</strong>s angoisses, <strong>de</strong> la mélancolie, <strong>de</strong><br />

l’impotence, <strong>de</strong>s troubles rénaux, <strong>de</strong> la matrice<br />

etc. Une distinction est faite entre les flatuosités<br />

lentes qui ne causent que peu <strong>de</strong> douleur aux<br />

mala<strong>de</strong>s tandis que celles qui sont impétueuses<br />

peuvent produire <strong>de</strong>s désordres cruels.<br />

La métho<strong>de</strong> curative <strong>de</strong> Fienus consiste en<br />

un régime régulier et en l’usage <strong>de</strong> carminatifs<br />

tels que l’anis, le fenouil et la coriandre. Ces<br />

médicaments variés, dont la composition est<br />

toujours fort compliquée, parfois associés à la<br />

thériaque, peuvent être administrés sous plusieurs<br />

formes: décoctions, clystères, pastilles,<br />

électuaires, sirops etc. Fienus s’étend longuement<br />

sur le traitement spécifique <strong>de</strong> chaque<br />

maladie provoquée par les flatulences.<br />

L’ouvrage <strong>de</strong> Fienus reflète bien une certaine<br />

mé<strong>de</strong>cine <strong>de</strong> la Renaissance qui conteste<br />

la tradition hippocratico-galénique et passe<br />

<strong>de</strong> la critique <strong>de</strong> texte à celle <strong>de</strong>s opinions.<br />

D’autre part il est certain que Fienus reste un<br />

homme <strong>de</strong> son époque, ayant du mal à se dégager<br />

<strong>de</strong>s croyances, <strong>de</strong>s superstitions en vigueur<br />

en ce temps-là et <strong>de</strong> la fascination que suscitent<br />

encore les mé<strong>de</strong>cins <strong>de</strong> l’Antiquité.

14 Jean-Pierre Tricot<br />

Après sa mort, et dans la lignée <strong>de</strong> Paracelse<br />

et <strong>de</strong> Van Helmont, l’iatrochimisme, un<br />

nouveau courant médical, voit le jour à Lei<strong>de</strong>n<br />

au 17 e siècle. Selon cette théorie tous les processus<br />

<strong>de</strong> vie et <strong>de</strong> maladie sont conditionnés par<br />

<strong>de</strong>s réactions chimiques: la digestion est une<br />

fermentation et l’absorption <strong>de</strong>s aliments est<br />

une sorte <strong>de</strong> phénomène d’évaporation. L’esprit<br />

vital est un produit <strong>de</strong> distillation du sang dans<br />

le cerveau. La thérapie consiste donc à corriger<br />

ce qui a été perturbé par la maladie dans ce<br />

laboratoire <strong>de</strong> chimie qu’est le corps humain.<br />

Une certaine analogie peut être faite avec les<br />

thèses défendues par Fienus, mais il faudra<br />

encore attendre <strong>de</strong> nombreuses décennies<br />

avant <strong>de</strong> voir appara”tre une véritable physiologie<br />

digestive permettant <strong>de</strong> mieux comprendre<br />

la pathologie.<br />

BIBLIOGRAPHIE:<br />

Broeckx C.: Essai sur l’histoire <strong>de</strong> la mé<strong>de</strong>cine belge. Leroux, Gand, Bruxelles et Mons, 1837<br />

De Nave F., De Schepper M, Tricot J.-P. eds. : De geneeskun<strong>de</strong> in <strong>de</strong> renaissance. Museum Plantin-Moretus,<br />

Antwerpen, 1990<br />

Elaut L.: Over win<strong>de</strong>n en windigheid, over florsen, flatus en flatulentie bij een Antwerps dokter uit <strong>de</strong> 16°<br />

eeuw. Periodiek (Vlaams Geneesheren Verbond) 23 : 27-36 (1968)<br />

Fienus J.: De flatibus humanum corpus molestantibus. Henricus ac Ghelius, Antverpiae, 1582. (Bruxelles,<br />

Bibl. Royale, VI 33.260 A LP)<br />

Gysel C.: L’odontalgie flatulente, concept médical à la Renaissance. Le Point n°105 : 35-37 (1995)<br />

Son<strong>de</strong>rvorst F.A.: Vie et ouvrages <strong>de</strong>s Feyens d’Anvers au XVI° siècle. Le Scalpel 110 : 1142-1148 (1957)<br />

Van Hee R.: Thomas Fijens (1567-1630 Chirurg te Antwerpen, hoogleraar te Leuven. Scientiarum Historia<br />

26 : 15-21 (2000)

AIR IN ANCIENT MEDICINE<br />

FROM PHYSIOLOGY AND PATHOLOGY<br />

TO THERAPY AND PHYSICS<br />

Alain Touwai<strong>de</strong><br />

Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC (USA)<br />

Air in ancient medicine was credited with an<br />

important role in both human constitution and<br />

diseases. Among the earliest records of medical<br />

practice, an entire treatise is <strong>de</strong>voted to it,<br />

together with water and sites. To confirm the<br />

importance it was credited with, this work is<br />

attributed to no less than Hippocrates (465-<br />

between 375 and 350 B.C.), although it was not<br />

written by him. Already the title of such work<br />

inclu<strong>de</strong>s the word air and even opens with it,<br />

immediately suggesting the function of air in<br />

ancient medicine: Airs, Waters, Places.<br />

After it was consi<strong>de</strong>red one of the first primary<br />

constituents of the world matter (with<br />

water, earth, and fire) by the first Greek philosophers<br />

(the so-called Pre-Socratics), air was<br />

credited with a fundamental role in the <strong>de</strong>velopment<br />

of human health and diseases. The<br />

Hippocratic treatise above, which has generally<br />

been (and still is) consi<strong>de</strong>red as the prototype<br />

of geo-medicine, analyzes the effect of winds<br />

on a set of elements that <strong>de</strong>termine human<br />

health: the waters, the parts of the body, the<br />

humors (that is, the physiological fluids of<br />

humans, supposed or actually existing), the<br />

constitution of humans, the epi<strong>de</strong>miology, and<br />

what the late Mirko Grmek suggested to call the<br />

pathocenosis. In a typical fashion, the treatise<br />

proceeds according to the four cardinal points,<br />

although it does not mention North and South<br />

explicitly, but refers to their main quality: cold<br />

for the wind coming from North and heat for<br />

the one coming from South.<br />

A clear structure comes out from this analysis,<br />

which can be summarized by the following<br />

figure:<br />

15

16 Alain Touwai<strong>de</strong><br />

North<br />

cold wind<br />

hard and cold water<br />

good digestive system<br />

major humor: bile<br />

strong and dry constitutions<br />

excess of dryness provokes ruptures<br />

West<br />

worst wind<br />

trouble waters<br />

generally weak constitution<br />

humoral system not purified<br />

unhealthy complexion<br />

all diseases<br />

East<br />

neither hot nor cold wind<br />

clear, pleasant, pure waters<br />

healthy complexion<br />

equilibrated physiology<br />

strong men, fertile women<br />

diseases of warm places (lesser and lighter)<br />

South<br />

warm wind<br />

salty and superficial waters<br />

humid and phlegmatic constitution<br />

phlegm from the head to the intestines<br />

complexion neither tonic nor strong<br />

women weak, men with dysentery, malaria, fever<br />

Typically, this quadripartite structure was<br />

linked with the seasons:<br />

Wind<br />

East<br />

South<br />

West<br />

North<br />

Season<br />

Spring<br />

Summer<br />

Autumn<br />

Winter<br />

No less typically, the best wind is that<br />

linked with the East, which presents the equilibrated<br />

qualities of Winter and Summer, that<br />

is, a balanced quantity of heat and cold, an<br />

equilibrated physiology, with solid men and fertile<br />

women who easily give birth, and with no<br />

disease especially fatal, even though they are<br />

those of warm places, but not so numerous and<br />

not so severe. In this view, winds and places on<br />

the West, for example, are unhealthy because<br />

waters are always foggy like Autumn; no organ<br />

is specifically strong or weak, but the general<br />

complexion is weak; people do not suffer from<br />

any specific disease, but from all in general.<br />

This way of conceiving the role of air in<br />

medicine changed radically later on. In the<br />

De materia medica by the Greek Dioscori<strong>de</strong>s<br />

(1 st cent. A.D.) —which analyzes all the natural<br />

substances of vegetal, animal, and mineral<br />

origin used for the preparation of medicines—,<br />

the different species of the several vegetal<br />

materia medica are i<strong>de</strong>ntified by means of

Air in Ancient Medicine. From Physiology and Pathology to Therapy and Physics 17<br />

many parameters, from the supposed gen<strong>de</strong>r<br />

of the plants to their environment. Within a<br />

genus (2.122), the species growing close to the<br />

sea is the cultivated one. It has larger leaves<br />

than the other species, which is a sign of <strong>de</strong>generation.<br />

Contrary to what might be expected,<br />

in<strong>de</strong>ed, cultivated species in Dioscori<strong>de</strong>s are<br />

consi<strong>de</strong>red as <strong>de</strong>generated when compared to<br />

the wild ones. Furthermore, proximity to water<br />

usually provokes weakness, as Dioscori<strong>de</strong>s explicitly<br />

mentions in the preface of this treatise<br />

where he discusses in a general way the<br />

therapeutic properties of the different species<br />

of plants (§ 6). Vegetal species in an alpine<br />

environment, instead, have thinner leaves in<br />

one case (4.9) or larger in another, but with<br />

a lower and <strong>de</strong>nser structure (3.110), and in a<br />

third case a stronger and bitter taste (3.99).<br />

There thus is an opposition of the species in<br />

which the alpine ones have a lower and <strong>de</strong>nser<br />

structure, with a stronger taste; by opposition,<br />

species close to water (be it the sea or any other<br />

form of water) are cultivated and weaker. As<br />

a consequence, there is a bi-polar system that<br />

opposes high-low, mountain-sea, strong-weak,<br />

wild-cultivated, tasty-tasteless, and highly therapeutic-less<br />

active.<br />

This opposition reminds the concepts of<br />

the Hippocratic treatise above, among others<br />

the notion of stagnant waters and the consecutive<br />

weakness of human conditions, or the<br />

strength and dryness of people exposed to cold<br />

winds. In Dioscori<strong>de</strong>s, these notions are transferred<br />

from humans to plants, the constitution<br />

of which —and hence also their <strong>medicina</strong>l<br />

properties— is <strong>de</strong>termined in the same way as<br />

the human conditions in Hippocratic medicine.<br />

In this view, the role of winds in the Hippocratic<br />

treatise (in fact, air) no longer affects humans<br />

in Dioscori<strong>de</strong>s, but the plants and the <strong>de</strong>gree of<br />

their therapeutic action.<br />

Later on, air was consi<strong>de</strong>red to generate<br />

the therapeutic properties themselves. This<br />

is the case in Galen (129-after 216 [?] A.D.), particularly<br />

in his monumental treatise on materia<br />

medica entitled On the mixtures and properties<br />

of simple medicines. As an example, one could<br />

quote the case of nettle: the aphrodisiac property<br />

it is credited with is explained by the presence<br />

of air in the structure of its matter (6.1.13).<br />

While this is the most advanced phase of an<br />

evolution that transferred first to the plants<br />

(Dioscori<strong>de</strong>s), and then to their properties (Galen)<br />

the Hippocratic system (which probably<br />

reproduced an archaic system of thinking), it is<br />

in fact a return to the system of the Pre-Socratic<br />

philosophers who speculated on the ultimate<br />

matter of which the world is ma<strong>de</strong>. According<br />

to them, it was ma<strong>de</strong> of four elements, air,<br />

earth, water, and fire.<br />

Air in ancient medicine went thus a long<br />

way, from health and pathology (through the<br />

environment and its impact on humans in<br />

Hippocratic medicine) to therapy (through the<br />

differentiation of vegetal species in Dioscori<strong>de</strong>s)<br />

and ultimately physics in the ancient<br />

meaning of the word (through the elements<br />

of which plants and other natural substances<br />

were supposedly ma<strong>de</strong> in Galen).<br />

BIBLIOGRAPHY<br />

On Hippocrates, see Jacques JOUANNA, Hip pocrate, Paris, 1992 (English translation: Hippocrates, Baltimore<br />

and London, 1999). For the Greek text (with an English translation) of Airs, Waters, Places, see W.H.S.

18 Alain Touwai<strong>de</strong><br />

Jones, Hippocrates, Airs, Waters, Places. Greek Translated by - (Loeb Classical Library 147). Cambridge<br />

(Mass.), and London, 1923, pp. 65-137.<br />

On Discori<strong>de</strong>s’ biography and pharmacological system, see: John M. RIDDLE, Dioscori<strong>de</strong>s on Pharmacy and<br />