Tichitt-Walata and the Middle Niger - PanAfrican Association of ...

Tichitt-Walata and the Middle Niger - PanAfrican Association of ...

Tichitt-Walata and the Middle Niger - PanAfrican Association of ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Aspects <strong>of</strong> Af rican Archaeology<br />

<strong>Tichitt</strong>-<strong>Walata</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Middle</strong> <strong>Niger</strong>: evidence for<br />

cultural contact in <strong>the</strong> second millennium Be<br />

KEVIN C. MACDoNALD<br />

Introduction: palaeohydrology <strong>and</strong> previous research<br />

A cultural connection between <strong>the</strong> <strong>Tichitt</strong>-<strong>Walata</strong> complex <strong>of</strong> sou<strong>the</strong>astern Mauritania <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> later<br />

civilisations <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Middle</strong> <strong>Niger</strong> has long been hypo<strong>the</strong>sised (McIntosh 1995; Holl 1985a; Munson<br />

1980). Soninke oral traditions concerning <strong>the</strong> origins <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Empire <strong>of</strong> Ghana (particularly <strong>the</strong> myth<br />

<strong>of</strong> Dinga; Dieterlen <strong>and</strong> Sylla 1992), affinities in ceramic traditions (McIntosh 1995), <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> existence<br />

<strong>of</strong> vestigial Soninke-speaking populations in <strong>the</strong> vicinity <strong>of</strong> <strong>Tichitt</strong> (Munson 1980) have all<br />

been used to assert population movement from Mauritania to <strong>the</strong> <strong>Middle</strong> <strong>Niger</strong> sometime before <strong>the</strong><br />

first millennium AD. It now appears that a fossil drainage <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Middle</strong> <strong>Niger</strong> supplies <strong>the</strong> concrete<br />

evidence for this interaction which has long been sought.<br />

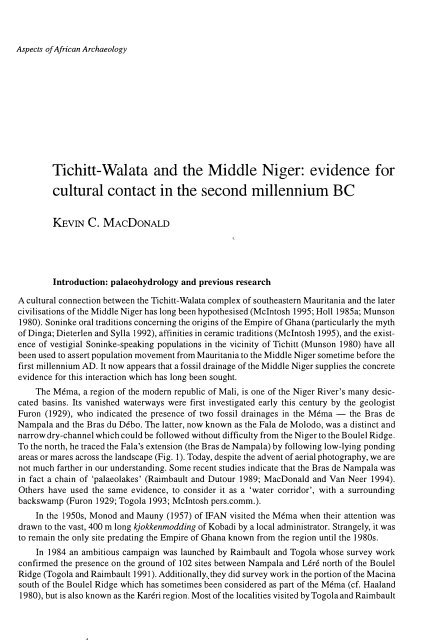

The Merna, a region <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> modern republic <strong>of</strong> Mali, is one <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Niger</strong> River's many desiccated<br />

basins. Its vanished waterways were first investigated early this century by <strong>the</strong> geologist<br />

Furon (1929), who indicated <strong>the</strong> presence <strong>of</strong> two fossil drainages in <strong>the</strong> Merna - <strong>the</strong> Bras de<br />

Nampala <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> Bras du Debo. The latter, now known as <strong>the</strong> Fala de Molodo, was a distinct <strong>and</strong><br />

narrow dry-channel which could be followed without difficulty from <strong>the</strong> <strong>Niger</strong> to <strong>the</strong> Boulel Ridge.<br />

To <strong>the</strong> north, he traced <strong>the</strong> Fala's extension (<strong>the</strong> Bras de Nampala) by following low-lying ponding<br />

areas or mares across <strong>the</strong> l<strong>and</strong>scape (Fig. 1). Today, despite <strong>the</strong> advent <strong>of</strong> aerial photography, we are<br />

not much far<strong>the</strong>r in our underst<strong>and</strong>ing. Some recent studies indicate that <strong>the</strong> Bras de Nampala was<br />

in fact a chain <strong>of</strong> 'palaeolakes' (Raimbault <strong>and</strong> Dutour 1989; MacDonald <strong>and</strong> Van Neer 1994).<br />

O<strong>the</strong>rs have used <strong>the</strong> same evidence, to consider it as a 'water corridor', with a surrounding<br />

backswamp (Furon 1929; Togola 1993; McIntosh pers.comm.).<br />

In <strong>the</strong> 1950s, Monod <strong>and</strong> Mauny (1957) <strong>of</strong> IFAN visited <strong>the</strong> Merna when <strong>the</strong>ir attention was<br />

drawn to <strong>the</strong> vast, 400 m long kjokkenmodding <strong>of</strong> Kobadi by a local administrator. Strangely, it was<br />

to remain <strong>the</strong> only site predating <strong>the</strong> Empire <strong>of</strong> Ghana known from <strong>the</strong> region until <strong>the</strong> 1980s.<br />

In 1984 an ambitious campaign was launched by Raimbault <strong>and</strong> Togola whose survey work<br />

confirmed <strong>the</strong> presence on <strong>the</strong> ground <strong>of</strong> 102 sites between Nampala <strong>and</strong> Lere north <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Boulel<br />

Ridge (Togola <strong>and</strong> Raimbault 1991). Additionally, <strong>the</strong>y did survey work in <strong>the</strong> portion <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Macina<br />

south <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Boulel Ridge which has sometimes been considered as part <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Merna (cf. Haal<strong>and</strong><br />

1980), but is also known as <strong>the</strong> Kareri region. Most <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> localities visited by Togola <strong>and</strong> Raimbault

430 Kevin C. MacDonald<br />

Figure 1<br />

<strong>of</strong> sites.<br />

\<br />

\<br />

I<br />

I, b.<br />

,.<br />

I<br />

"<br />

,<br />

I<br />

,<br />

,<br />

,<br />

,<br />

I<br />

I<br />

... ... ...<br />

,<br />

KEY<br />

Mauritania<br />

Ndondl To •• ok.1 }b.<br />

b.<br />

Map <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Merna region showing principal geomorphological features <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> distribution<br />

- - --<br />

I<br />

I<br />

I<br />

I<br />

I<br />

I<br />

I b. I<br />

I<br />

Ill.<br />

o J<br />

* Nampala<br />

b.<br />

Kobadl<br />

•<br />

, __ ,I Limits <strong>of</strong> Holocene Floodplain<br />

Palaeochannels<br />

Escarpment<br />

Modern Ponding Areas<br />

o Kollma<br />

&<br />

Central Basin<br />

* Toladl'<br />

, .<br />

, ,<br />

F<br />

ossil Dunes<br />

Pr incipal Facies by Site<br />

•<br />

o<br />

*<br />

Kobadi<br />

Faita<br />

10 km<br />

Beretouma<br />

Goudlodle<br />

Ndond i Tossoke I<br />

No Predominant Assemblage<br />

Modern Villages<br />

.. .", - --

<strong>Tichitt</strong>-<strong>Walata</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Middle</strong> <strong>Niger</strong>: evidence for cultural contact in <strong>the</strong> second millennium Be 431<br />

were large tell sites, with only one fur<strong>the</strong>r 'Neolithic' site, that <strong>of</strong> Tiabel Goudiodie, being discovered.<br />

Raimbault has since returned to <strong>the</strong> Merna to excavate at Kobadi (Raimbault et al. 1987;<br />

Raimbault <strong>and</strong> Dutour 1989).<br />

The 1989 <strong>and</strong> 1990 Merna Survey<br />

In <strong>the</strong> winter <strong>of</strong> 1989/1990 a systematic survey <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Merna region was carried out by T. Togola <strong>and</strong><br />

myself. The purpose <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> mission was to establish a cultural chronology for <strong>the</strong> region, particularly<br />

with a view to studying changes in site distribution <strong>and</strong> environmental change over time. After<br />

<strong>the</strong> survey, several sites were selected for test excavations to allow <strong>the</strong> chronological placement <strong>of</strong><br />

surface materials. In total 137 archaeological sites were visited, surface collected, <strong>and</strong> plotted on<br />

aerial photos during our survey. The work <strong>of</strong> Togola was presented as his doctoral <strong>the</strong>sis (Togola<br />

1993), while my work on <strong>the</strong> project formed a portion <strong>of</strong> my own (MacDonald 1994).<br />

Until <strong>the</strong> present decade, occupation sites pre-dating <strong>the</strong> advent <strong>of</strong> metallurgy were a rarity in<br />

<strong>the</strong> vicinity <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> modern delta . Indeed, no vestiges <strong>of</strong>\human occupation from before 200 cal BC<br />

are yet known from <strong>the</strong> interior <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> modern Inl<strong>and</strong> <strong>Niger</strong> Delta itself, a phenomenon attributed<br />

tentatively to alluviation <strong>and</strong>/or to highly seasonal settlements before this time (R.J. McIntosh 1983).<br />

Remarkably, <strong>the</strong> Merna survey succeeded in locating 28 sites belonging to what has conventionally<br />

been termed <strong>the</strong> 'LSA' or 'Neolithic' .<br />

Four distinCt ceramic facies were identified at <strong>the</strong>se 28 sites, representing two broad cultural<br />

traditions. Each facies was named after a type assemblage most clearly representing all <strong>of</strong> its facets<br />

(Kobadi, Beretouma, Ndondi Tossokel <strong>and</strong> Faita). It should be stressed, however, that although<br />

assemblages were invariably dominated by a single set <strong>of</strong> wares, materials attributable to o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

facies were usually also represented in <strong>the</strong>m. Test excavation <strong>and</strong> surface associations indicate that<br />

three <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se facies were at least partially contemporaneous, whilst <strong>the</strong> fourth (Faita facies) represents<br />

a later phase in <strong>the</strong> region's occupation (ca. 800BC - AD 200). The three contemporary facies<br />

would appear to date to between 2000 <strong>and</strong> 800 Be on <strong>the</strong> basis <strong>of</strong> an admittedly small suite <strong>of</strong> eight<br />

radiocarbon dates from three sites (MacDonald 1994, MacDonald <strong>and</strong> Van Neet 1994). For <strong>the</strong><br />

purposes <strong>of</strong> this paper we will limit discussion to this period.<br />

Kobadi facies, Kobadi tradition (Fig. 2)<br />

First characterised by Mauny (1972), Kobadi ceramics are characterised by thick-walled, open <strong>and</strong><br />

restricted simple-rimmed vessels <strong>of</strong> a usually globular shape. The internal rim diameters <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se<br />

vessels usually range from 28 to 40 cm.<br />

They are decorated principally with pivoting stylus <strong>and</strong> pivoted, dragged or rocked comb (24-<br />

60% <strong>of</strong> motif occurrences). O<strong>the</strong>r important means <strong>of</strong> decor include: twine impression (usually<br />

along <strong>the</strong> rim), braided twine roulettes (cf. Hurley 1979; types 210-212), twisted twine roulettes (cf.<br />

Soper 1985: 36), fabric impression (cf. Bedaux <strong>and</strong> Lange 1983) <strong>and</strong> incised or complex punctate<br />

decors <strong>of</strong>ten rendered in 'wavy' patterns (cf. Fig. 2.c-d).<br />

Temper is one <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> most distinctive elements <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Kobadi Tradition. Sponge spicules <strong>and</strong><br />

coarse s<strong>and</strong> were virtually <strong>the</strong> only tempers utilised in Kobadi wares. There is an increasing literature<br />

concerning sponge spiCUle temper in African pottery (cf. Brissaud <strong>and</strong> Houdayer 1986; Adamson<br />

et al. 1987; McIntosh <strong>and</strong> MacDonald 1989). In <strong>the</strong> Merna, we are dealing with high content samples<br />

which contain spicules only (no gemmules or gemulscleres), almost certainly indicative <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

genus Potamolipis (a freshwater sponge, indigenous throughout <strong>the</strong> <strong>Niger</strong> River system) (McIntosh<br />

<strong>and</strong> MacDonald 1989). Spicule content, measured by thin-section point counts, in samples from<br />

Kobadi <strong>and</strong> Tiabel Goudiodie, may be placed at 18 to 25% <strong>of</strong> content (200 point samples). This<br />

measure far exceeds that for known <strong>Middle</strong> <strong>Niger</strong> pottery <strong>of</strong> later periods. Such quantities would

432 Kevin C. MacDonald<br />

2<br />

I<br />

}<br />

I<br />

I--- -- -- --<<br />

20cm<br />

Figure 2 Typical Wares <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Kobadi Facies: a= pivoted stylus <strong>and</strong> impressed fabric decor [1251-1],<br />

b= twine impressed, pivoted comb <strong>and</strong> impressed fabric decor [1251-1], c=simple incised <strong>and</strong> impressed<br />

cord-wrapped stick decor [Beretouma 1121-2], d= complex punctate <strong>and</strong> stabbed comb decor [Tiabel<br />

Goudiodie].<br />

Figure 3 Typical Beretouma Ware: a=stabbed comb <strong>and</strong> twisted cord roulette [Kolima-Sud], b=rocker<br />

comb, simple incision <strong>and</strong> twisted cord roulette [Beretouma 1121-5], c= rocker comb <strong>and</strong> twisted cord<br />

roulette [Kolima-Sud).<br />

Figure 4 Typical Wares <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Ndondi Tossokel Facies: a= cord-wrapped stick roulette [Kolima-Sud],<br />

b=simple incised <strong>and</strong> impressed cord-wrapped stick [1251-2], c=cord-wrapped stick roulette [Ndondi<br />

Tossokel 1119-1].<br />

Figure 5. Dhar <strong>Tichitt</strong> Tradition Ceramics from <strong>the</strong> Chebka <strong>and</strong> Arriane Phases: a= cord-wrapped<br />

stick roulette [Munson site 16], b= cord-wrapped stick roulette [Munson site 22], c= impressed cord<br />

wrapped stick [Munson site 22], d= simple incision <strong>and</strong> cord-wrapped cord roulette [Munson site 46].

<strong>Tichitt</strong>- <strong>Walata</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Middle</strong> <strong>Niger</strong>: evidence for cultural contact in <strong>the</strong> second millennium Be 433<br />

argue for some sort <strong>of</strong> intentional concentration <strong>of</strong> spicules in <strong>the</strong> clay: ei<strong>the</strong>r through <strong>the</strong> intentional<br />

ga<strong>the</strong>ring <strong>of</strong> clay from dry season floodplains'where dead sponges are clustered, or through<br />

<strong>the</strong> physical grinding, burning or macerating <strong>of</strong> whole specimens. The latter practices have been<br />

demonstrted along <strong>the</strong> White Nile between 3500 <strong>and</strong> 1500 BP by Adamson et at. (1987). Sponge<br />

spicule tempering would appear to be a distinctive technology, associated with peoples exploiting<br />

riverine resources.<br />

Aside from pottery, Kobadi facies localities possess a plethora <strong>of</strong> bone points, hooks <strong>and</strong> (more<br />

rarely) harpoons. Additionally, polished stone points are known from excavated contexts (Raimbault<br />

<strong>and</strong> Dutour 1987; MacDonald 1994). Stope grinders <strong>and</strong> objets de parure are rare. Geometric<br />

microliths though present at earlier localities (i.e. Tiabel Goudiodie), seem to disappear in favour <strong>of</strong><br />

a crude assortment <strong>of</strong> retouched flakes at later sites (e.g. Kobadi <strong>and</strong> Kolima-Sud).<br />

All Kobadi facies sites occur within <strong>the</strong> bounds <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> ancient floodplain (Fig. 1). All <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

sites are kjokkenmoddings, <strong>and</strong> were probably initially chosen for occupation because <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir elevation<br />

above <strong>the</strong> surrounding plain. At Kobadi, excavations by Raimbault have shown that <strong>the</strong><br />

original site surface was 1-2 m above <strong>the</strong> floodplain (Raimbault <strong>and</strong> Dutour 1989), <strong>and</strong> similar<br />

results have been achieved by our team at Kolima Sud ' (MacDonald 1994, MacDonald <strong>and</strong> Van<br />

Neer 1994). Additionally, at Kobadi it appears that <strong>the</strong> habitation area stretched along <strong>the</strong> top <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

bone midden <strong>and</strong> burial area, although no post holes or daub fragments have yet been reported.<br />

1251-1 follows <strong>the</strong> same pattern as Kobadi in terms <strong>of</strong> shape, except that it would have been situated<br />

on an islet within a lake. Tiabel Goudiodie is an enormous shell midden <strong>of</strong> over 3m in height<br />

situated directly beside <strong>the</strong> ancient Fala de Molodo channel.<br />

In size, <strong>the</strong> sites <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Kobadi facies far exceed <strong>the</strong>ir peers, ranging between 1.9 <strong>and</strong> 7.6 ha in<br />

expanse. This may be due to greater population aggregations at Kobadi localities, a permanent as<br />

opposed to a seasonal occupation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> sites, <strong>the</strong>ir depositional nature (kjokkenmoddings), or to a<br />

longer period <strong>of</strong> occupation for <strong>the</strong>se sites (with horizontal displacements).<br />

Economically, <strong>the</strong> Kobadi facies would appear to be 'hunter-fisher', with catfish, Tilapia, Nile<br />

perch <strong>and</strong> aquatic mammals dominating faunal assemblages (Raimbault et at. 1987, MacDonald<br />

<strong>and</strong> Van Neer 1994).<br />

Beretouma facies, Kobadi tradition (Fig. 3)<br />

The Beretouma facies is perhaps best regarded as a phase <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Kobadi tradition ra<strong>the</strong>r than as a<br />

discrete entity. It is characterised by distinctive simple rimmed, open bowls with internal diameters<br />

varying between 34 <strong>and</strong> 48 cm, although a few smaller vessels (c.24 cm) are known.<br />

Their decor is highly distinctive, consisting <strong>of</strong> twisted <strong>and</strong> braided twine roulettes on <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

exterior, burnishing <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir lip <strong>and</strong> interior, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> decoration <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> interior with one rank <strong>of</strong><br />

rocker comb decor. The vessels are also unique in being consistently black in colour (fired in a<br />

reducing atmosphere). In terms <strong>of</strong> temper, only 12% <strong>of</strong> such vessels recovered in <strong>the</strong> survey were<br />

grog tempered, <strong>the</strong> remainder were tempered with sponge.<br />

There are three localities located in <strong>the</strong> survey which bear quantities <strong>of</strong> Beretouma ware associated<br />

with Kobadi <strong>and</strong> Ndondi Tossokel ceramics. They are all <strong>of</strong> substantial size, <strong>the</strong> largest being<br />

<strong>the</strong> 12.5 ha site <strong>of</strong> Kolima Sud. The remaining two, 1121-4 <strong>and</strong> 1121-5 are both situated on <strong>the</strong><br />

raised beaches which form a ring around <strong>the</strong> sou<strong>the</strong>rn portion <strong>of</strong> "Palaeolake Beretouma". Both<br />

sites are semi-circular high density artifact scatters abutting <strong>the</strong> lake bed.<br />

We have little economic evidence associated with Beretouma pottery o<strong>the</strong>r than numerous fish<br />

remains (MacDonald 1994).

434 Kevin C. MacDonald<br />

Ndondi Tossokelfacies, Dhar <strong>Tichitt</strong> tradition (Fig. 4)<br />

Elements <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Ndondi Tossokel tradition first appeared like uninvited guests in elements <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

Kobadi assemblage illustrated by Mauny (1972: Plate n.8-10). In retrospect, parallels between <strong>the</strong>se<br />

vessels <strong>and</strong> those from <strong>Tichitt</strong>-<strong>Walata</strong> should have been obvious at <strong>the</strong> time (Mauny 1972: Plates V<br />

VII; Holl 1986: Fig.23). However it was not until I had a chance to study <strong>the</strong> Dhar <strong>Tichitt</strong> assemblage<br />

curated by Pat Munson at Indiana University in 1993, that I realised <strong>the</strong> Ndondi Tossokel<br />

tradition <strong>and</strong> that <strong>of</strong> <strong>Tichitt</strong>-<strong>Walata</strong> to be one <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> same (compare Figs 4 <strong>and</strong> 5).<br />

The Ndondi Tossokel tradition comprises both open simple-rimmed vessels <strong>and</strong> closed evertedrimmed<br />

vessels, with <strong>the</strong> latter being <strong>the</strong> more numerous. The everted rim vessels have internal rim<br />

diameters <strong>of</strong> between 12 <strong>and</strong> 22 cm. The diameters <strong>of</strong> open simple rimmed vessels range between<br />

14 <strong>and</strong> 38 cm.<br />

In addition to <strong>the</strong> distinctive shape <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir everted rims (cf. Fig. 4 for <strong>the</strong> three principal variations),<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir decor <strong>and</strong> its manner <strong>of</strong> application are most characteristic. Tightly spaced cord-wrapped<br />

cord roulettes descending vertically from <strong>the</strong> lip or collar <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> vessel are a hallmark <strong>of</strong> Ndondi<br />

Tossokel wares, comprising between 39 <strong>and</strong> 59% <strong>of</strong> total motif occurrences. Additionally, impressions<br />

using <strong>the</strong> same tool are common. O<strong>the</strong>r decor attributes include applied plastic nubbins <strong>and</strong><br />

fillets (cf. Rye 1981: 94) which are usually in <strong>the</strong> shape <strong>of</strong> teats <strong>and</strong> are applied below or within <strong>the</strong><br />

b<strong>and</strong> <strong>of</strong> cord-wrapped stick decor, <strong>and</strong> simple incised lines or arcs (Fig. 4b). Red slip is also very<br />

common, with traces visible on <strong>the</strong> lip <strong>of</strong> most vessels. The fabric <strong>of</strong> Ndondi Tossokel pottery is<br />

distinctive, usually consisting <strong>of</strong> grog <strong>and</strong> coarse s<strong>and</strong>, sometimes augmented by chaff (ca. 5-30%<br />

<strong>of</strong> sherds depending on <strong>the</strong> assemblage). In texture, <strong>the</strong>y are harder than Beretouma or Kobadi<br />

wares, <strong>and</strong> tend to have thinner walls.<br />

Although lithics are scarce in <strong>the</strong> Merna, probably due to <strong>the</strong> lack <strong>of</strong> local rock sources aside<br />

from schist <strong>and</strong> s<strong>and</strong>stone, Ndondi Tossokel sites usually provide an assortment <strong>of</strong> projectile points<br />

comparable to those known from Dhars <strong>Tichitt</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Walata</strong> (cf. Amblard 1984, types 68, 78 <strong>and</strong> 79).<br />

Also, polished stone hachettes, stone rings <strong>and</strong> beads which correlate well with <strong>the</strong> findings <strong>of</strong><br />

Amblard (1984) are associated with <strong>the</strong> Ndondi Tossokel facies.<br />

In most instances <strong>the</strong> Ndondi Tossokel sites are characterised by <strong>the</strong> presence <strong>of</strong> what may be<br />

called "mini-middens". These are relatively small, one to five metre diameter, rounded mounds no<br />

more than 50 cm in height containing broken pottery, stone chips <strong>and</strong> bone. In between <strong>the</strong>se <strong>the</strong>re<br />

is only a thin scatter <strong>of</strong> cultural materials. Munson (pers. comm.) has suggested that similar "bumps"<br />

observed in <strong>the</strong> Dhar <strong>Tichitt</strong> region, were wind-eroded rubbish pits or sherd-lined earth ovens.<br />

Alternatively, <strong>the</strong>se could be <strong>the</strong> remains <strong>of</strong> refuse accumulations from beside living areas, or even<br />

hydrological phenomena. Still, it is interesting that "mini-middens;' do not occur at sites <strong>of</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

traditions situated within <strong>the</strong> inundatable plain.<br />

Except when <strong>the</strong>y are mixed with Beretouma ceramics, Ndondi Tossokel facies sites do not<br />

occur within <strong>the</strong> ancient floodplain, but on its margins (Fig. 1). They feature little debris accumulation,<br />

with <strong>the</strong>ir deposits never rising more than a metre above <strong>the</strong> surrounding area. In size <strong>the</strong>y are<br />

much smaller than Kobadi sites, usually not exceeding 1.5 ha. A notable exception to this is <strong>the</strong> 6 ha<br />

escarpment-top occupation <strong>of</strong> Saberi Faita, but it is only superficially stratified. These sites give <strong>the</strong><br />

impression <strong>of</strong> ephemeral occupations by highly mobile groups.<br />

Cattle <strong>and</strong> ovicaprine remains, as well as terracotta cattle statuettes, have been positively associated<br />

with Ndondi Tossokel facies ceramics at Kolima-Sud <strong>and</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r sites (MacDonald 1994).<br />

This brings into question claims <strong>of</strong> Raimbault (et al. 1987) concerning <strong>the</strong> association <strong>of</strong> cattle<br />

remains with <strong>the</strong> Kobadi tradition. As has been argued elsewhere, we believe it more probable that<br />

cattle remains at Kobadi stem from intrusive Ndondi Tossokel facies deposits at <strong>the</strong> site (MacDonald<br />

<strong>and</strong> Van Neer 1994).

<strong>Tichitt</strong>- <strong>Walata</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Middle</strong> <strong>Niger</strong>: evidence for cultural contact in <strong>the</strong> second millennium Be 435<br />

Figure 6 Outlying sites <strong>and</strong> regions discussed in <strong>the</strong> text with radiating lines showing likely sources<br />

<strong>of</strong> stone imports found in <strong>the</strong> Merna from ca. 2000-800 Be.<br />

/ 1'1<br />

\<br />

\<br />

I<br />

I<br />

\ r--_ .... .<br />

MAURITANIA<br />

\ ,.. -...J --- ____ _<br />

/ ----------b__J<br />

• Nar8<br />

MALI<br />

Dhar <strong>Tichitt</strong> Tradition Ceramics (Figure 6)<br />

250km<br />

• Hassi el Ablod<br />

Some mention should be made here concerning <strong>the</strong> main aspects <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Tichitt</strong> ceramic tradition to<br />

which parallels have been drawn. Although presented extensively in Munson's (1971) <strong>the</strong>sis, a<br />

detailed characterisation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se assemblages has never been published. It should be evident from<br />

what follows that I still subscribe to Munson's (1971, 1976) chronological hypo<strong>the</strong>sis, albeit with<br />

some modifications, <strong>and</strong> not to Holl's (1986) seasonality hypo<strong>the</strong>sis. Most <strong>of</strong> my reasons can be<br />

found in Munson's own rebuttal to Holl (Munson 1989), but I would also stress <strong>the</strong> integrity <strong>and</strong><br />

clarity <strong>of</strong> Munson's original ceramic sequence.<br />

The earliest <strong>Tichitt</strong> ceramics, those assigned to <strong>the</strong> Akreijit through Goungou phases (I-III), are<br />

strictly simple rimmed vessels. All are chaff tempered, <strong>and</strong> decor consists initially <strong>of</strong> comb decor<br />

gradually replaced in turn by impressed cord wrapped stick <strong>and</strong> twisted twine roulettes. Chaff in

436 Kevin C. MacDonald<br />

fact remains <strong>the</strong> almost exclusive temper <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Tichitt</strong> tradition .throughout its long span <strong>of</strong> years,<br />

with s<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> grog occasionally added or substituted. Everted rims, as well as red slip, only begin to<br />

appear in <strong>the</strong> Nkahl <strong>and</strong> Naghez phases (IV-V), with twisted twine remaining <strong>the</strong> dominant decor.<br />

By <strong>the</strong> Chebka <strong>and</strong> Arriane phases (VI-VII) everted rims have become common accounting for<br />

c.40-50% <strong>of</strong> all rims. Cord-wrapped stick motifs become common again, <strong>and</strong> start to be used as<br />

roulettes instead <strong>of</strong> only for impression (cf. Fig. 5 for ceramics from phases VI-VII). Finally, in <strong>the</strong><br />

AkJinjeir phase (VIII) applied plastic motifs become common, <strong>and</strong> vessels grow much larger <strong>and</strong><br />

have less decor.<br />

The <strong>Tichitt</strong> assemblages only become analogous with those· <strong>of</strong> Ndondi Tossokel'during <strong>the</strong><br />

Chebka <strong>and</strong> Arriane phases (e.g. higher proportions <strong>of</strong> everted rims, rouletted cord-wrapped decor,<br />

etc.). Their resemblance is not absolute, however, as some <strong>Tichitt</strong> vessels <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se phases feature<br />

knotted twine decor (cf. Hurley 1979: Type 165), a manipulation entirely absent in <strong>the</strong> Merna.<br />

Discussion: regional chronology<br />

Dating <strong>the</strong> Kobadi facies<br />

The earliest known date for <strong>the</strong> human occupation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Middle</strong> <strong>Niger</strong> comes from <strong>the</strong> site <strong>of</strong> Tiabel<br />

Goudiodie. This site has been dated on freshwater oyster shells (E<strong>the</strong>ria elliptica) to between 2570<br />

<strong>and</strong> 2410 cal BC (Togola <strong>and</strong> Raimbault 1991). As usual with dates on freshwater materials, however,<br />

a carbonate reservoir effect <strong>of</strong> several hundred years should be allowed for, thus an initial<br />

occupation date <strong>of</strong> around 2000 BC is more likely for <strong>the</strong> site.<br />

It is difficult to know what <strong>the</strong> sequence <strong>of</strong> dates from <strong>the</strong> site <strong>of</strong> Kobadi actually date culturally,<br />

since all but one <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>m are conventional collagen dates run on surface-collected bone, <strong>and</strong><br />

Ndondi Tossokel materials are known to also occur on <strong>the</strong> site (Raimbault <strong>and</strong> Dutour 1989,<br />

MacDonald 1994). The earliest date, 1740-1510 BC, was run on burned hippopotamus bone, <strong>and</strong> is<br />

thus most likely associated with <strong>the</strong> aquatically based Kobadi tradition. More recently, an as yet<br />

incompletely published date (Georgeon et al. 1992: 86) was run on an unspecified material from <strong>the</strong><br />

1989 excavations. Its result, 1740-1440 BC (3305±80 BP), is very close to that <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> early 'hippo<br />

bone'. The middle dates are less certain, coming from indeterminate burned bone (1260-900 BC)<br />

<strong>and</strong> mammalian vertebrae (930-610 BC) respecti vely, <strong>the</strong> latter date coming from samples collected<br />

by Mauny in 1954 (Georgeon et at. 1992). The most recent date (770 to 380 BC) was run on <strong>the</strong><br />

cranium <strong>of</strong> a late inhumation recovered eroding from <strong>the</strong> midden surface. It is evident that we are<br />

dealing with a lengthy <strong>and</strong> probably multi-faceted occupation at Kobadi (c. 1750-400 BC). How<br />

punctuated this may have been by gaps in occupation, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> extent to which typical Kobadi wares<br />

continued throughout it, will only be clarified with <strong>the</strong> publication <strong>of</strong> a complete excavation report<br />

by Raimbault.<br />

A single radiocarbon date has recently been run on hippo ivory from <strong>the</strong> lowest Kobadi facies<br />

occupation layer <strong>of</strong> Kolima-Sud (layer V, KLS- l lv.25). The result <strong>of</strong> this apatite determination was<br />

as follows: 3365±70 BP11740-1530 cal BC (GX-21192-AMS). This date is comparable to <strong>the</strong> two<br />

earliest dates from Kobadi itself, <strong>and</strong> when bracketed by a date associated with Ndondi-Tossokel<br />

ceramics in <strong>the</strong> upper Kolima-Sud sequence (see below), suggests a minimum temporal range <strong>of</strong><br />

1750 to 1300 BC for <strong>the</strong> Kobadi facies.<br />

Dating <strong>the</strong> Ndondi Tossokel <strong>and</strong> Beretouma facies<br />

Test excavations carried out at <strong>the</strong> site <strong>of</strong> Kolima-Sud in 1990 provide our only definitive date for<br />

Ndondi Tossokel <strong>and</strong> Beretouma ceramics in context. There, two sondages revealed occupational<br />

deposits <strong>of</strong> 2.5 m in depth containing four principal occupational layers (MacDonald 1994). In

<strong>Tichitt</strong>- <strong>Walata</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Middle</strong> <strong>Niger</strong>: evidence for cultural contact in <strong>the</strong> second millennium Be 437<br />

layers I to III cattle remains <strong>and</strong> cattle figurines appear with Ndondi Tossokel ceramics. Kobadi<br />

ceramics, which were present from <strong>the</strong> sites first occupation (layers IV <strong>and</strong> V), disappear before<br />

layer III <strong>and</strong> are replaced fully by Beretouma ceramics which continue beside those <strong>of</strong> Ndondi<br />

Tossokel. In <strong>the</strong> absence <strong>of</strong> substantive charcoal deposits, a cattle molar (Bos cf taurus, M2) from<br />

<strong>the</strong> Layer IIIIII interface (KLS-l, Iv. 1 0) was submitted to Geochron Laboratories for apatite dating.<br />

The result was: 3084±73 BP11420-1230 cal BC (GX-19814-AMS) (MacDonald <strong>and</strong> Van Neer 1994).<br />

Also, at least for <strong>the</strong> dating <strong>of</strong> N dondi Tossokel tradition, we may turn to <strong>the</strong> Dhar <strong>Tichitt</strong> Phase<br />

VI-VII Chebkal Arriane wares with which it is closely stylistically associated. The calibration <strong>of</strong><br />

dates assigned by Munson (1989) to <strong>the</strong>se phases, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> poorly chronologically defined Naghez<br />

phase, would place <strong>the</strong>ir one sigma range between 1400 <strong>and</strong> 800 Be. This would appear to be in line<br />

with our single date from <strong>the</strong> Merna. But here, unfortunately, we venture onto <strong>the</strong> much debated<br />

ground <strong>of</strong> Dhar <strong>Tichitt</strong> chronology (Holl 1986; Munson 1989; Muzzolini 1989). Suffice to say that<br />

ano<strong>the</strong>r re-evaluation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Dhar <strong>Tichitt</strong> sequence is in progress, which will hopefully clarify this<br />

matter for <strong>the</strong> time being (MacDonald <strong>and</strong> Munson in prep.).<br />

Conclusion: <strong>the</strong> Merna before <strong>the</strong> Empire <strong>of</strong> Ghana<br />

In <strong>the</strong> Merna we have a particularly early West African example <strong>of</strong> multi-cultural contemporaneity<br />

within a single region. There are at least two groups involved. The Kobadi Tradition, with physical<br />

<strong>and</strong> material cultural roots to <strong>the</strong> nor<strong>the</strong>ast at Hassi el Abiod (Raimbault <strong>and</strong> Dutour 1989, Georgeon<br />

et al. 1992), <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> Ndondi Tossokel tradition with material <strong>and</strong> economic roots to <strong>the</strong> northwest at<br />

Dhars <strong>Tichitt</strong>-<strong>Walata</strong>.<br />

The earlier occupants <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> region are manifestly <strong>the</strong> Kobadi folk, robust "Mechtoid" fisherhunter-ga<strong>the</strong>rers<br />

who first colonised <strong>the</strong> shrinking lacustrine region around 2000 Be. Human osteology<br />

has been used to link <strong>the</strong>m with similar early Holocene fisher-hunter-ga<strong>the</strong>rer populations<br />

from <strong>the</strong> Saharan site <strong>of</strong> Hassi el Abiod (Georgeon et al. 1992). Their movement to <strong>the</strong> Merna has<br />

been portrayed as a response to environmental change - a retreat with <strong>the</strong> lacustrine regions which<br />

maintained <strong>the</strong>ir aquatic subsistence lifestyle. Upon <strong>the</strong>ir arrival in <strong>the</strong> Merna, <strong>the</strong>y were still producing<br />

a geometric microlith industry, but this seems to have given way to an opportunistic utilised<br />

flake industry (MacDonald 1994). Their hunting <strong>and</strong> fishing prowess in this virgin l<strong>and</strong>scape appears<br />

to have been epic, with kills <strong>of</strong> elephants, hippos, crocodiles, <strong>and</strong> massive Nile perch <strong>and</strong><br />

catfish <strong>of</strong> up to 2.5 m in length. Only at Kobadi <strong>and</strong> Kolima Sud, where ceramics <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Ndondi<br />

Tossokel facies are associated, do we have any evidence for food production associated with <strong>the</strong><br />

Kobadi tradition.<br />

Around 1300 BC we have evidence that a new group had entered <strong>the</strong> zone with close affinities<br />

to Dhar <strong>Tichitt</strong>'s ChebkalArriane phase (c.1400-800 BC). It would seem that <strong>the</strong> Dhar <strong>Tichitt</strong> tradition,<br />

with only small quantities <strong>of</strong> arable l<strong>and</strong>, had long been under pressure to exp<strong>and</strong>. Indeed,<br />

settlement hierarchies first visible at Dhars <strong>Tichitt</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Walata</strong> around this time may represent traces<br />

<strong>of</strong> simple chiefdoms organised to defend <strong>the</strong> decreasing supply <strong>of</strong> l<strong>and</strong> (Munson 1980; Holl 1985a).<br />

It is even possible that population pressures <strong>and</strong> territorial restrictions were responsible for a shift to<br />

<strong>the</strong> actual domestication <strong>of</strong> millet at <strong>the</strong> site (Munson 1976; Amblard <strong>and</strong> Pemes 1989). From this<br />

time, <strong>of</strong>f-shoots <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Dhar <strong>Tichitt</strong> tradition begin to appear in small mobile settlements along <strong>the</strong><br />

margins <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Merna's inundatable plain. Their economy would seem to have been based on pastoralism,<br />

but we have no data to show us whe<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong>y were also cultivators. Could <strong>the</strong>y represent a<br />

pastoral sub-group <strong>of</strong> a Dhar <strong>Tichitt</strong> cultural complex? Or, were <strong>the</strong>y true agro-pastoralists for whom<br />

<strong>the</strong> Merna was only a grazing <strong>and</strong> shallow-water fishing stop on an elaborate seasonal round? We do<br />

not yet know.

438 Kevin C. MacDonald<br />

That <strong>the</strong>re was movement between <strong>the</strong> Merna <strong>and</strong> <strong>Tichitt</strong>-<strong>Walata</strong> is evidenced by imported<br />

stone materials <strong>of</strong> Phthanite, Amazonite <strong>and</strong> Jasper from Mauritania. Indeed, it is possible that<br />

Ndondi Tossokel <strong>and</strong> Kobadi trade contact long predates <strong>the</strong> first arrival <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> former's settlements<br />

in <strong>the</strong> region. Above all, trade could have been in <strong>the</strong> form <strong>of</strong> commodities: rare stones <strong>and</strong> cattle for<br />

fish <strong>and</strong> possibly grain.<br />

Around 1300 BC it would also appear that <strong>the</strong> Kobadi tradition underwent a shift, with <strong>the</strong><br />

appearance <strong>of</strong> Ben5touma ware. This may simply represent a later phase <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Kobadi tradition, but<br />

it is notable that Beretouma ceramics occur frequently on sites where Kobadi <strong>and</strong> Ndondi-Tossokel<br />

ceramics co-exist. Is it possible that <strong>the</strong> Beretouma tradition might instead be a product <strong>of</strong> contact<br />

between <strong>the</strong>se two groups? In some cases <strong>the</strong> two populations appear to have lived side by side, or<br />

at <strong>the</strong> very least <strong>the</strong>re was a seasonal trade between <strong>the</strong>m.<br />

Evidence to support this assertion comes from <strong>the</strong> pastoral element <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Ndondi Tossokel<br />

economy. If <strong>the</strong> cattle had not yet developed tsetse resistance, a substantial seasonal displacement to<br />

<strong>the</strong> north would have been essential for <strong>the</strong>ir herds survival, <strong>and</strong> would have constituted a barrier to<br />

any southward penetration <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> zone (Smith 1979). Even if <strong>the</strong>ir livestock were tsetse resistant, it<br />

would have been difficult for <strong>the</strong>m to have survived in a floodplain environment during <strong>the</strong> wet<br />

season if only for reasons <strong>of</strong> space <strong>and</strong> ho<strong>of</strong>-rot. In any event, <strong>the</strong>ir displacements need not have<br />

been <strong>the</strong> vast migrations practised by modern pastoral groups. Wet season settlements could even<br />

have been located less than 50 km away, at <strong>the</strong> Mauritanian s<strong>and</strong>stone inselbergs <strong>of</strong> which Saberi<br />

Faita is <strong>the</strong> sou<strong>the</strong>rnmost. Questions <strong>of</strong> this nature will remain unanswerable until work is continued<br />

in <strong>the</strong> Merna, <strong>and</strong> survey is conducted in <strong>the</strong> adj9ining Dhar Nema region.<br />

Acknowledgements<br />

I would like to thank Tereba Togola for our long-st<strong>and</strong>ing friendship <strong>and</strong> continuing collaboration.<br />

I am also grateful to Patrick Munson for access to collections <strong>and</strong> some enlightening discussions.<br />

Funding for my participation in <strong>the</strong> Merna Project was supplied by a Thomas J. Watson Fellowship<br />

(1989/90).<br />

References<br />

Adamson, D., Clark, J.D. <strong>and</strong> Williams, M.AJ. 1987. Pottery tempered with sponge from <strong>the</strong><br />

White Nile, Sudan. African Archaeological Review 5: 115-27.<br />

Amblard, S. 1984. <strong>Tichitt</strong>-<strong>Walata</strong> (R.I. Mauritanie): civilisation et industrie lithique. Paris:<br />

Editions Recherches sur les Civilisations, Memoire no. 35.<br />

Amblard, S. <strong>and</strong> Pernes, J. 1989. The identification <strong>of</strong> cultivated pearl millet (Pennisetum)<br />

amongst plant impressions on pottery from Oued Chebbi (Dhar Oualata, Mauritania). African<br />

Archaeological Review 7: 117-26.<br />

Bedaux, R.M.A. <strong>and</strong> Lange, A.G. 1983. Tellem reconnaissance archeologique d' une culture de<br />

l'Ouest Africain au Moyen Age: la poterie. Journal des Africanistes 53: 5-59.<br />

Brissaud, 1. <strong>and</strong> Houdayer, A. 1986. Sponge spicules as characteristic <strong>of</strong> ancient African pottery<br />

from Mali. Journal <strong>of</strong> Field Archaeology 13: 357-8.<br />

Dieterlen, G. <strong>and</strong> Sylla, D. 1992. L'Empire de Ghana: Ie Wagadou et les traditions de yerere.<br />

Paris: Editions Karthala.<br />

Furon, R. 1929. L'ancien delta du <strong>Niger</strong> (Contribution a l'etude de l'hydrographie ancienne du<br />

Sahel Soudanais). Revue de Geographie Physique et Geologie Dynamique 2: 265-74.<br />

Georgeon, E., Dutour, O. <strong>and</strong> Raimbault, M. 1992. Paleoanthropologie du gisement lacustre<br />

neolithique de Kobadi (Mali). Prehistoire et Anthropologie Mediterraneennes 1: 85-97.

<strong>Tichitt</strong>-WaLata <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> MiddLe <strong>Niger</strong>: evidence jar cultural contact in <strong>the</strong> second millennium Be 439<br />

Haal<strong>and</strong>, R. 1980. Man's role in <strong>the</strong> changing habitat <strong>of</strong> Merna during <strong>the</strong> Old Kingdom <strong>of</strong><br />

Ghana. Norwegian Archaeological Review 13: 31-46.<br />

Holl, A. 1985a. Background to <strong>the</strong> Ghana Empire: archaeological investigations on <strong>the</strong> transition<br />

to statehood in <strong>the</strong> Dhar <strong>Tichitt</strong> region (Mauritania). lournal <strong>of</strong> Anthropological Archaeology<br />

4: 73-115.<br />

Holl, A. 1985b. Subsistence patterns <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Dhar <strong>Tichitt</strong> Neolithic, Mauritania. African<br />

Archaeological Review 3: 151-62.<br />

Holl, A. 1986. Economie et Societe Neolithique du Dhar <strong>Tichitt</strong> (Mauritanie). Paris: Editions<br />

Recherche sur les Civilisations, Memoire no. 69.<br />

Holl, A. 1989. Habitat et societes prehistoriques du Dhar <strong>Tichitt</strong> (Mauritanie). Sahara 2: 49-60.<br />

Hurley, W. 1979. Prehistoric Cordage: identifications <strong>of</strong> impressions on pottery. Washington:<br />

Taraxacum.<br />

MacDonald, K.C. 1994. Socio-economic diversity <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> origins <strong>of</strong> cultural complexity along<br />

<strong>the</strong> <strong>Middle</strong> <strong>Niger</strong> (2000 BC to AD 300). PhD <strong>the</strong>sis, eambridge University.<br />

MacDonald, K.C. <strong>and</strong> Munson, P. in prep. Ceramics, ecology, <strong>and</strong> cultural chronology:. new light<br />

on <strong>the</strong> Dhar <strong>Tichitt</strong> debate from <strong>the</strong> <strong>Middle</strong> <strong>Niger</strong>. African Archaeological Review.<br />

MacDonald, K.C. <strong>and</strong> Van Neer, W. 1994. Specialised fishing peoples along <strong>the</strong> <strong>Middle</strong> <strong>Niger</strong>:<br />

evidence from <strong>the</strong> later Holocene <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Merna Region (Mali). In Fish Exploitation in <strong>the</strong> Past<br />

(ed. W. Van Neer): pp.243-51. Tervuren: Musee Royal de l' Afrique Centrale.<br />

McIntosh, R. J. 1983. Floodplain geomorphology <strong>and</strong> human occupation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Upper Inl<strong>and</strong><br />

Delta <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Niger</strong>. The Geographical lournal149: 182-201.<br />

McIntosh, S.K. (ed.) 1995. Excavations at lenne-leno, Hamarketolo, <strong>and</strong> Kaniana (Inl<strong>and</strong> <strong>Niger</strong><br />

Delta, Mali), <strong>the</strong> 1981 Season. Berkeley: University <strong>of</strong> California Press.<br />

McIntosh, S.K. <strong>and</strong> MacDonald, K.C. 1989. Sponge spicules in pottery: new data from Mali.<br />

Journal <strong>of</strong> Field Archaeology 16: 489-94.<br />

Mauny, R. 1972. Contribution a l' inventaire de la cerami que neolithique d' Afrique Occidentale.<br />

Actes de 6e Congres Panafricain de Prehistoire, Dakar 1967 (ed. HJ. Hugot): pp.72-9.<br />

Chambery: Les Imprimeries Reunies.<br />

Monod, T. <strong>and</strong> Mauny, R. 1957. Decouverte de nouveaux instruments en os dans l'Ouest Africain.<br />

Proceedings <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> 3rd Panafrican Congress on Prehistory, Livingstone 1955 (ed. J.D. Clark):<br />

pp.242-47. London: Chatto <strong>and</strong> Windus.<br />

Munson, PJ. 1971. The <strong>Tichitt</strong> Tradition: a late prehistoric occupation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> southwestern<br />

Sahara. Ph.D. <strong>the</strong>sis, University <strong>of</strong> Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.<br />

Munson, P.J. 1976. Archaeological data on <strong>the</strong> origins <strong>of</strong> cultivation in <strong>the</strong> southwestern Sahara<br />

<strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir implications for West Africa. In Origins <strong>of</strong> African Plant Domestication (eds. 1. de<br />

Wet <strong>and</strong> A. Stemmler): pp.l87-209. The Hague: Mouton.<br />

Munson, PJ. 1980. Archaeology <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> prehistoric origins <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Ghana Empire. Journal <strong>of</strong><br />

African History 21: 457-66.<br />

Munson, PJ. 1989. About economie et societe neolithique du Dhar <strong>Tichitt</strong> (Augustin Holl).<br />

Sahara 2: 107-9.<br />

Muzzolini, A. 1989. Essay review: a reappraisal <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> 'Neolithic' <strong>of</strong> <strong>Tichitt</strong> (Mauritania).<br />

lournal <strong>of</strong> Arid Environments 16: 101-5.<br />

Raimbault, M. 1990. Pour une approche du Neolithique du Sahara Malien. Travaux du LAPMO,<br />

1990 pp.67-81.

440 Kevin C. MacDonald<br />

Raimbault, M. <strong>and</strong> Dutour, O. 1989. Les nouvelles donnees du·site neolithique de Kobadi dans Ie<br />

Sahel malien: la mission 1989. Travaux de LAPMO, 1989 pp.175-83.<br />

Raimbault, M., Guerin, C. <strong>and</strong> Faure, M. 1987. Les vertebres du gisement neolithique de Kobadi.<br />

Archaeozoologia 1: 219-38.<br />

Rye, O. 1981. Pottery Technology: principles <strong>and</strong> reconstruction. Washington: Taraxacum.<br />

Smith, A.B. 1979. Biogeographical considerations <strong>of</strong> colonization <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> lower Tilemsi Valley in<br />

<strong>the</strong> second millennium B.C. Journal <strong>of</strong> Arid Environments 2: 355-61.<br />

Soper, R. 1985. Roulette decoration on African pottery: technical considerations, dating <strong>and</strong><br />

distributions. African Archaeological Review 3: 29-51.<br />

Togola, T. 1993. Archaeological investigations <strong>of</strong> Iron Age sites in <strong>the</strong> Mema region (Mali). Ph.D.<br />

<strong>the</strong>sis, Rice University.<br />

Togola, T. <strong>and</strong> Rairnbault, M. 1991. Les missions d'inventaire dans Ie Merna, Kareri et Farimake.<br />

In Recherches Archeologiques au Mali: Les sites protohistorique de la zone lacustre (eds. M.<br />

Raimbault <strong>and</strong> K. Sanogo ): pp.81-98. Paris: ACCT-Karthala.