Whitefly and whitefly-borne viruses in the tropics : Building a ... - cgiar

Whitefly and whitefly-borne viruses in the tropics : Building a ... - cgiar

Whitefly and whitefly-borne viruses in the tropics : Building a ... - cgiar

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

About <strong>the</strong> Partners<br />

CIAT<br />

The International Center for Tropical Agriculture (CIAT) is a not-for-profit organization that conducts<br />

socially <strong>and</strong> environmentally progressive research aimed at reduc<strong>in</strong>g hunger <strong>and</strong> poverty <strong>and</strong><br />

preserv<strong>in</strong>g natural resources <strong>in</strong> develop<strong>in</strong>g countries. CIAT is one of <strong>the</strong> 15 centers funded ma<strong>in</strong>ly<br />

by <strong>the</strong> 58 countries, private foundations, <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>ternational organizations that make up <strong>the</strong><br />

Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR).<br />

IITA<br />

IITA’s mission is to enhance <strong>the</strong> food security, <strong>in</strong>come, <strong>and</strong> well-be<strong>in</strong>g of resource-poor people <strong>in</strong><br />

sub-Saharan Africa by conduct<strong>in</strong>g research <strong>and</strong> related activities to <strong>in</strong>crease agricultural production,<br />

improve food systems, <strong>and</strong> susta<strong>in</strong>ably manage natural resources, <strong>in</strong> partnership with national<br />

<strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>ternational stakeholders.<br />

AVRDC<br />

AVRDC is <strong>the</strong> pr<strong>in</strong>cipal <strong>in</strong>ternational center for vegetable research <strong>and</strong> development <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> world.<br />

Its mission is to reduce poverty <strong>and</strong> malnutrition <strong>in</strong> develop<strong>in</strong>g countries through improved<br />

production <strong>and</strong> consumption of vegetables.<br />

CIP<br />

The International Potato Center (CIP) seeks to reduce poverty <strong>and</strong> achieve food security on a<br />

susta<strong>in</strong>ed basis <strong>in</strong> develop<strong>in</strong>g countries through scientific research <strong>and</strong> related activities on<br />

potato, sweetpotato, <strong>and</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r root <strong>and</strong> tuber crops <strong>and</strong> on <strong>the</strong> improved management of natural<br />

resources <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Andes <strong>and</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r mounta<strong>in</strong> areas.<br />

ICIPE<br />

ICIPE’s mission is to help alleviate poverty, ensure food security <strong>and</strong> improve <strong>the</strong> overall health<br />

status of peoples of <strong>the</strong> <strong>tropics</strong> by develop<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> extend<strong>in</strong>g management tools <strong>and</strong> strategies for<br />

harmful <strong>and</strong> useful arthropods, while preserv<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> natural resource base through research <strong>and</strong><br />

capacity build<strong>in</strong>g.<br />

About <strong>the</strong> Donors<br />

DANIDA<br />

Reduc<strong>in</strong>g poverty <strong>in</strong> develop<strong>in</strong>g countries is central to Danish development cooperation priorities.<br />

A number of crosscutt<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong>mes are built <strong>in</strong>to DANIDA’s development assistance: women’s<br />

participation <strong>in</strong> development, <strong>the</strong> environment, promotion of democracy <strong>and</strong> observation of human<br />

rights. These crosscutt<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong>mes are <strong>in</strong>tegrated <strong>in</strong>to DANIDA’s development activities more generally.<br />

DFID<br />

The United K<strong>in</strong>gdom’s Department for International Development (DFID) supports research <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

susta<strong>in</strong>able management of natural resources that aims at improv<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> livelihoods of poor people<br />

<strong>in</strong> develop<strong>in</strong>g countries. DFID has funded commodity-based research on whiteflies <strong>and</strong> <strong>whitefly</strong>transmitted<br />

<strong>viruses</strong>, primarily <strong>in</strong> Africa, for nearly a decade through its centrally funded Crop<br />

Protection Programme (CPP). It is now aim<strong>in</strong>g to build on this support by help<strong>in</strong>g to create a global<br />

framework that will allow different <strong>whitefly</strong> research projects <strong>and</strong> activities to coord<strong>in</strong>ate <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

efforts more effectively <strong>and</strong> produce research outputs which have positive <strong>and</strong> susta<strong>in</strong>able impacts<br />

on poor peoples’ livelihoods.<br />

NZAID<br />

NZAID is New Zeal<strong>and</strong>’s agency responsible for <strong>in</strong>ternational assistance to develop<strong>in</strong>g countries.<br />

New Zeal<strong>and</strong>’s aid helps to elim<strong>in</strong>ate poverty <strong>and</strong> create a safe <strong>and</strong> just world, particularly <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

Pacific region.<br />

USAID<br />

USAID is an <strong>in</strong>dependent federal government agency that receives overall foreign policy guidance<br />

from <strong>the</strong> Secretary of State. USAID supports long-term <strong>and</strong> equitable economic growth <strong>and</strong> advances<br />

U.S. foreign policy objectives by support<strong>in</strong>g: economic growth, agriculture <strong>and</strong> trade; global<br />

health; <strong>and</strong>, democracy, conflict prevention <strong>and</strong> humanitarian assistance.<br />

USDA<br />

Provides leadership on food, agriculture, natural resources, <strong>and</strong> related issues based on sound<br />

public policy, <strong>the</strong> best available science, <strong>and</strong> efficient management.

ISBN 958-694-074-8<br />

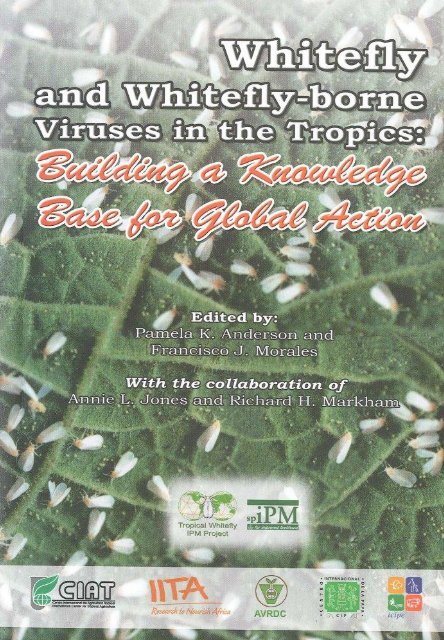

<strong>Whitefly</strong><br />

<strong>and</strong> <strong>Whitefly</strong>-<strong>borne</strong><br />

Viruses <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Tropics:<br />

Build<strong>in</strong>g a Knowledge<br />

Base for Global Action<br />

Edited by:<br />

Pamela K. Anderson <strong>and</strong><br />

Francisco J. Morales<br />

With <strong>the</strong> collaboration of<br />

Annie L. Jones <strong>and</strong> Richard H. Markham

Centro Internacional de Agricultura Tropical<br />

International Center for Tropical Agriculture<br />

Apartado Aéreo 6713<br />

Cali, Colombia<br />

Fax: +57 (2) 4450073<br />

E-mail: f.morales@<strong>cgiar</strong>.org<br />

CIAT Publication No. 341<br />

ISBN 958-694-074-8<br />

Press run: 500<br />

Pr<strong>in</strong>ted <strong>in</strong> Colombia<br />

August 2005<br />

<strong>Whitefly</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>whitefly</strong>-<strong>borne</strong> <strong>viruses</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>tropics</strong>: Build<strong>in</strong>g a knowledge base for global action /<br />

edited by Pamela K. Anderson <strong>and</strong> Francisco J. Morales; with <strong>the</strong> collaboration of Annie L. Jones<br />

<strong>and</strong> Richard H. Markham. Cali, CO : Centro Internacional de Agricultura Tropical (CIAT), 2005.<br />

351 p. -- (CIAT publication no. 341)<br />

ISBN 958-694-074-8<br />

AGROVOC descriptors <strong>in</strong> English:<br />

1. Manihot esculenta. 2. Ipomoea batatas. 3. Sweet potatoes. 4. Vegetables. 5. Legumes.<br />

6. Pest <strong>in</strong>sects. 7. Aleyrodidae. 8. Bemisia tabaci. 9. Trialeurodes vaporariorum.<br />

10. Aleurotrachelus socialis. 11. Trialeurodes variabilis. 12. Bemisia tuberculata. 13. Trialeurodes<br />

abutiloneus. 14. Aleurocanthus woglumi. 15. Cassava mosaic virus. 16. Gem<strong>in</strong>i<strong>viruses</strong>. 17. Vectors.<br />

18. Food security. 19. Poverty. 20. Pest control. 21. Disease control. 22. Biological control.<br />

23. Integrated control. 24. Parasitoids. 25. Natural enemies. 26. Resistance to chemicals.<br />

27. Socioeconomic environment. 28. PCR. 29. RAPD. 30. Mixed cropp<strong>in</strong>g. 31. Highl<strong>and</strong>s.<br />

32. Capacity build<strong>in</strong>g. 33. Africa. 34. Central America. 35. Mexico. 36. Caribbean. 37. Lat<strong>in</strong><br />

America.<br />

Local descriptors <strong>in</strong> English:<br />

1. Cassava. 2. <strong>Whitefly</strong>. 3. Molecular techniques.<br />

AGROVOC descriptors <strong>in</strong> Spanish:<br />

1. Manihot esculenta. 2. Ipomoea batatas. 3. Batatas. 4. Hortalizas. 5. Legum<strong>in</strong>osas.<br />

6. Insectos dañ<strong>in</strong>os. 7. Aleyrodidae. 8. Bemisia tabaci. 9. Trialeurodes vaporariorum.<br />

10. Aleurotrachelus socialis. 11. Trialeurodes variabilis. 12. Bemisia tuberculata. 13. Trialeurodes<br />

abutiloneus. 14. Aleurocanthus woglumi. 15. Virus del mosaico de la cassava. 16. Gem<strong>in</strong>ivirus.<br />

17. Vectores. 18. Seguridad alimentaria. 19. Pobreza. 20. Control de plagas. 21. Control de<br />

enfermedades. 22. Control biológico. 23. Control <strong>in</strong>tegrado. 24. Parasitoides. 25. Enemigos<br />

naturales. 26. Resistencia a productos químicos. 27. Entorno socioeconómico. 28. PCR.<br />

29. RAPD. 30. Cultivo mixto. 31. Zona de montaña. 32. Creación de capacidad. 33. África.<br />

34. América Central. 35. México. 36. Caribe. 37. América Lat<strong>in</strong>a.<br />

Local descriptors <strong>in</strong> Spanish:<br />

1. Yuca. 2. Mosca blanca. 3. Técnicas moleculares.<br />

I. Anderson, Pamela K. II. Morales, Francisco José. III. Centro Internacional de Agricultura<br />

Tropical. IV. Ser.<br />

AGRIS subject categories: H10 Pests of plants / Plagas de plantas<br />

H20 Plant diseases / Enfermedades de las plantas<br />

LC classification: SB 945 .W4 W4<br />

Copyright CIAT 2005. All rights reserved<br />

CIAT encourages wide dissem<strong>in</strong>ation of its pr<strong>in</strong>ted <strong>and</strong> electronic publications for maximum public benefit.<br />

Thus, <strong>in</strong> most cases colleagues work<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> research <strong>and</strong> development should feel free to use CIAT materials<br />

for noncommercial purposes. However, <strong>the</strong> Center prohibits modification of <strong>the</strong>se materials, <strong>and</strong> we<br />

expect to receive due credit. Though CIAT prepares its publications with considerable care, <strong>the</strong> Center<br />

does not guarantee <strong>the</strong>ir accuracy <strong>and</strong> completeness.

Contents<br />

Page<br />

Foreword vii<br />

Introduction<br />

Pamela K. Anderson 1<br />

SECTION ONE<br />

Whiteflies as Vectors of Plant Viruses <strong>in</strong> Cassava <strong>and</strong><br />

Sweetpotato <strong>in</strong> Africa<br />

Chapter<br />

1.1 Introduction<br />

James Legg 15<br />

1.2 Ghana<br />

Anthony Cudjoe, Joseph Gyamenah <strong>and</strong> Braima James 24<br />

1.3 Ben<strong>in</strong><br />

Brice Gbaguidi, Braima James <strong>and</strong> Symphorien Saizonou 30<br />

1.4 Nigeria<br />

Nnamdi C. Echendu, Joseph B. Ojo, Braima James <strong>and</strong><br />

Brice Gbaguidi 35<br />

1.5 Cameroon<br />

Nelson Ntonifor, Braima James, Brice Gbaguidi <strong>and</strong><br />

Ambe Tumanteh 40<br />

1.6 Ug<strong>and</strong>a<br />

Peter Sseruwagi, James Legg <strong>and</strong> William Otim-Nape 46<br />

1.7 Kenya<br />

Joseph Kamau, Peter Sseruwagi <strong>and</strong> Valente Aritua 54<br />

1.8 Tanzania<br />

Joseph Ndunguru, Simon Jeremiah, Reg<strong>in</strong>a Kap<strong>in</strong>ga <strong>and</strong><br />

Peter Sseruwagi 61<br />

iii

Chapter<br />

4<br />

Whiteflies <strong>and</strong> <strong>Whitefly</strong>-<strong>borne</strong> Viruses <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Tropics<br />

Page<br />

1.9 Malawi<br />

Ma<strong>the</strong>ws P. K. J. Theu <strong>and</strong> Peter Sseruwagi 68<br />

1.10 Madagascar<br />

Sahondramalala Ranomenjanahary, Jocelyn Ramelison <strong>and</strong><br />

Peter Sseruwagi 72<br />

1.11 The Diversity of Cassava Mosaic Begomo<strong>viruses</strong> <strong>in</strong> Africa<br />

Peter Markham, Robert Briddon, Clotilde Roussot,<br />

John Farquhar, Geoffrey Okao-Okuja <strong>and</strong> James Legg 77<br />

1.12 Serological Analysis of Sweetpotatoes Affected by Sweetpotato<br />

Virus Disease <strong>in</strong> East Africa<br />

Valente Aritua, Richard Gibson <strong>and</strong> Josef Vetten 83<br />

1.13 Factors Associated with Damage to Sweetpotato Crops by<br />

Sweetpotato Virus Disease<br />

Richard Gibson, Valente Aritua <strong>and</strong> Simon Jeremiah 89<br />

1.14 Conclusions <strong>and</strong> Recommendations<br />

James Legg <strong>and</strong> Braima James 98<br />

SECTION TWO<br />

Whiteflies as Pests <strong>and</strong> Vectors of Viruses <strong>in</strong> Vegetable <strong>and</strong><br />

Legume Mixed Cropp<strong>in</strong>g Systems <strong>in</strong> Eastern <strong>and</strong><br />

Sou<strong>the</strong>rn Africa<br />

2.1 Introduction<br />

Mohamed Ali Bob, Rebecca Ra<strong>in</strong>i <strong>and</strong> Bernhard Löhr 115<br />

2.2 Sudan<br />

Gassim Dafalla <strong>and</strong> Musa Ahmed 118<br />

2.3 Kenya<br />

Mohamed Ali Bob, Benjam<strong>in</strong> Odhiambo, Gilbert Kibata <strong>and</strong><br />

Jason Ong’aro 129<br />

2.4 Tanzania<br />

Ignas Swai <strong>and</strong> Simon Slumpa 141<br />

2.5 Malawi<br />

Harriet Th<strong>in</strong>dwa <strong>and</strong> Patric Khonje 150<br />

2.6 Tomato Yellow Leaf Curl Virus <strong>and</strong> Tomato Leaf Curl-like<br />

Viruses <strong>in</strong> Eastern <strong>and</strong> Sou<strong>the</strong>rn Africa<br />

Remi Nono-Womdim, Ignas Swai, Madan Mohan Lal Chadha <strong>and</strong><br />

Sylvia Green 157<br />

2.7 Conclusions <strong>and</strong> Recommendations<br />

Lisbeth Riis, Thomas Njuguna, Rebecca Ra<strong>in</strong>i, Berhard Löhr<br />

<strong>and</strong> Mohamed Ali Bob 163<br />

iv

Contents<br />

Chapter<br />

SECTION THREE<br />

Whiteflies as Vectors of Viruses <strong>in</strong> Legume <strong>and</strong> Vegetable<br />

Mixed Cropp<strong>in</strong>g Systems <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Tropical Lowl<strong>and</strong>s of<br />

Central America, Mexico <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> Caribbean<br />

Page<br />

3.1 Introduction<br />

Francisco Morales 173<br />

3.2 Mexico<br />

Francisco Morales, Rafael Rivera-Bustamante,<br />

Rafael Sal<strong>in</strong>as Pérez, Ir<strong>in</strong>eo Torres-Pacheco, Raúl Díaz Plaza,<br />

Wilson Avilés Baeza <strong>and</strong> Genovevo Ramírez Jaramillo 177<br />

3.3 Guatemala<br />

Francisco Morales, Abelardo Viana, Margarita Palmieri,<br />

Mónica Orozco <strong>and</strong> René Ruano 188<br />

3.4 El Salvador<br />

Francisco Morales, Carlos Pérez, Priscila Henríquez,<br />

Re<strong>in</strong>a de Serrano, Leopoldo Serrano <strong>and</strong> Claudio Nunes 197<br />

3.5 Honduras<br />

Francisco Morales, María Mercedes Doyle, Rogerio Traban<strong>in</strong>o,<br />

Carol<strong>in</strong>a Nolasco, Elsa Barrientos, Luís Jara <strong>and</strong> Norman Escoto 204<br />

3.6 Nicaragua<br />

Francisco Morales, Alberto Sediles, Aurelio Llano <strong>and</strong><br />

Falguni Guharay 210<br />

3.7 Costa Rica<br />

Francisco Morales, Luko Hilje, Juan Vallejos, Guillermo Sibaja,<br />

Carlos Araya <strong>and</strong> Rodolfo Araya 217<br />

3.8 Panama<br />

Francisco Morales, Orencio Fernández <strong>and</strong> José Guerra 222<br />

3.9 Haiti<br />

Francisco Morales, Jackson Donis <strong>and</strong> Emmanuel Prophete 226<br />

3.10 Cuba<br />

Francisco Morales, Gloria González, Carlos Murguido,<br />

Ana Echemendía, Yol<strong>and</strong>a Martínez, Yenín Hernández,<br />

Benito Faure <strong>and</strong> María Chailloux 230<br />

3.11 Dom<strong>in</strong>ican Republic<br />

Francisco Morales, Emigdio Gómez, Augusto Villar <strong>and</strong><br />

Julio N<strong>in</strong> 237<br />

3.12 Reproductive Crop Hosts of Bemisia tabaci (Gennadius)<br />

<strong>in</strong> Lat<strong>in</strong> America <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> Caribbean<br />

Pamela K. Anderson, Avas Hamon, Pilar Hernández <strong>and</strong><br />

Jon Mart<strong>in</strong> 243<br />

v<br />

5

Chapter<br />

6<br />

Whiteflies <strong>and</strong> <strong>Whitefly</strong>-<strong>borne</strong> Viruses <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Tropics<br />

Page<br />

3.13 Us<strong>in</strong>g Molecular Techniques to Analyse <strong>Whitefly</strong> Species <strong>and</strong><br />

Biotypes <strong>in</strong> Lat<strong>in</strong> America<br />

Lee Calvert, Natalia Villarreal <strong>and</strong> Donald Frohlich 251<br />

3.14 Conclusions <strong>and</strong> Recommendations<br />

Francisco Morales 263<br />

SECTION FOUR<br />

Whiteflies as Pests of Annual Crops <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Tropical<br />

Highl<strong>and</strong>s of Lat<strong>in</strong> America<br />

4.1 Introduction<br />

César Cardona 269<br />

4.2 Colombia <strong>and</strong> Ecuador<br />

César Cardona, Aristóbulo López-Avila <strong>and</strong> Oswaldo Valarezo 274<br />

4.3 Insecticide Resistance <strong>in</strong> Colombia <strong>and</strong> Ecuador<br />

César Cardona, Francisco Rendón, Isaura Rodríguez <strong>and</strong><br />

Aristóbulo López-Avila 285<br />

4.4 Conclusions <strong>and</strong> Recommendations<br />

César Cardona, Aristóbulo López-Avila <strong>and</strong> Oswaldo Valarezo 295<br />

SECTION FIVE<br />

Special Topics on Pest <strong>and</strong> Disease Management<br />

5.1 Susta<strong>in</strong>able Integrated Management of Whiteflies through<br />

Host Plant Resistance<br />

Anthony Bellotti, Joseph Tohme, Michael Dunbier <strong>and</strong><br />

Gail Timmerman 303<br />

5.2 Biological Control of Whiteflies by Indigenous Natural Enemies<br />

for Major Food Crops <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Neo<strong>tropics</strong><br />

Anthony Bellotti, Jorge Peña, Bernardo Arias,<br />

José María Guerrero, Harold Trujillo, Claudia Holguín <strong>and</strong><br />

Adriana Ortega 313<br />

5.3 Progress of Cassava Mosaic Disease <strong>in</strong> Ug<strong>and</strong>an Cassava<br />

Varieties <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong> Varietal Mixtures<br />

William Sserubombwe, Michael Thresh, James Legg <strong>and</strong><br />

William Otim-Nape 324<br />

5.4 Management of <strong>the</strong> Cassava Mosaic Disease P<strong>and</strong>emic <strong>in</strong><br />

East Africa<br />

James Legg, James Whyte, Reg<strong>in</strong>a Kap<strong>in</strong>ga <strong>and</strong> James Teri 332<br />

Conclusions<br />

Francisco Morales 339<br />

Acronyms <strong>and</strong> Abbreviations 345<br />

vi

CIAT Publication No. 341<br />

Integrated Pest <strong>and</strong> Disease Management Project<br />

<strong>and</strong><br />

Communications Unit<br />

Editorial assistance: Gladys Rodríguez<br />

Production: Graphic Arts Unit, CIAT<br />

Oscar Idárraga (layout)<br />

Julio C. Martínez (cover design)<br />

Pr<strong>in</strong>t<strong>in</strong>g: Arte Libro Impresores, Cali, Colombia

Contents<br />

Page<br />

Foreword vii<br />

Introduction<br />

Pamela K. Anderson 1<br />

SECTION ONE<br />

Whiteflies as Vectors of Plant Viruses <strong>in</strong> Cassava <strong>and</strong><br />

Sweetpotato <strong>in</strong> Africa<br />

Chapter<br />

1.1 Introduction<br />

James Legg 15<br />

1.2 Ghana<br />

Anthony Cudjoe, Joseph Gyamenah <strong>and</strong> Braima James 24<br />

1.3 Ben<strong>in</strong><br />

Brice Gbaguidi, Braima James <strong>and</strong> Symphorien Saizonou 30<br />

1.4 Nigeria<br />

Nnamdi C. Echendu, Joseph B. Ojo, Braima James <strong>and</strong><br />

Brice Gbaguidi 35<br />

1.5 Cameroon<br />

Nelson Ntonifor, Braima James, Brice Gbaguidi <strong>and</strong><br />

Ambe Tumanteh 40<br />

1.6 Ug<strong>and</strong>a<br />

Peter Sseruwagi, James Legg <strong>and</strong> William Otim-Nape 46<br />

1.7 Kenya<br />

Joseph Kamau, Peter Sseruwagi <strong>and</strong> Valente Aritua 54<br />

1.8 Tanzania<br />

Joseph Ndunguru, Simon Jeremiah, Reg<strong>in</strong>a Kap<strong>in</strong>ga <strong>and</strong><br />

Peter Sseruwagi 61<br />

iii

Chapter<br />

4<br />

Whiteflies <strong>and</strong> <strong>Whitefly</strong>-<strong>borne</strong> Viruses <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Tropics<br />

Page<br />

1.9 Malawi<br />

Ma<strong>the</strong>ws P. K. J. Theu <strong>and</strong> Peter Sseruwagi 68<br />

1.10 Madagascar<br />

Sahondramalala Ranomenjanahary, Jocelyn Ramelison <strong>and</strong><br />

Peter Sseruwagi 72<br />

1.11 The Diversity of Cassava Mosaic Begomo<strong>viruses</strong> <strong>in</strong> Africa<br />

Peter Markham, Robert Briddon, Clotilde Roussot,<br />

John Farquhar, Geoffrey Okao-Okuja <strong>and</strong> James Legg 77<br />

1.12 Serological Analysis of Sweetpotatoes Affected by Sweetpotato<br />

Virus Disease <strong>in</strong> East Africa<br />

Valente Aritua, Richard Gibson <strong>and</strong> Josef Vetten 83<br />

1.13 Factors Associated with Damage to Sweetpotato Crops by<br />

Sweetpotato Virus Disease<br />

Richard Gibson, Valente Aritua <strong>and</strong> Simon Jeremiah 89<br />

1.14 Conclusions <strong>and</strong> Recommendations<br />

James Legg <strong>and</strong> Braima James 98<br />

SECTION TWO<br />

Whiteflies as Pests <strong>and</strong> Vectors of Viruses <strong>in</strong> Vegetable <strong>and</strong><br />

Legume Mixed Cropp<strong>in</strong>g Systems <strong>in</strong> Eastern <strong>and</strong><br />

Sou<strong>the</strong>rn Africa<br />

2.1 Introduction<br />

Mohamed Ali Bob, Rebecca Ra<strong>in</strong>i <strong>and</strong> Bernhard Löhr 115<br />

2.2 Sudan<br />

Gassim Dafalla <strong>and</strong> Musa Ahmed 118<br />

2.3 Kenya<br />

Mohamed Ali Bob, Benjam<strong>in</strong> Odhiambo, Gilbert Kibata <strong>and</strong><br />

Jason Ong’aro 129<br />

2.4 Tanzania<br />

Ignas Swai <strong>and</strong> Simon Slumpa 141<br />

2.5 Malawi<br />

Harriet Th<strong>in</strong>dwa <strong>and</strong> Patric Khonje 150<br />

2.6 Tomato Yellow Leaf Curl Virus <strong>and</strong> Tomato Leaf Curl-like<br />

Viruses <strong>in</strong> Eastern <strong>and</strong> Sou<strong>the</strong>rn Africa<br />

Remi Nono-Womdim, Ignas Swai, Madan Mohan Lal Chadha <strong>and</strong><br />

Sylvia Green 157<br />

2.7 Conclusions <strong>and</strong> Recommendations<br />

Lisbeth Riis, Thomas Njuguna, Rebecca Ra<strong>in</strong>i, Berhard Löhr<br />

<strong>and</strong> Mohamed Ali Bob 163<br />

iv

Contents<br />

Chapter<br />

SECTION THREE<br />

Whiteflies as Vectors of Viruses <strong>in</strong> Legume <strong>and</strong> Vegetable<br />

Mixed Cropp<strong>in</strong>g Systems <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Tropical Lowl<strong>and</strong>s of<br />

Central America, Mexico <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> Caribbean<br />

Page<br />

3.1 Introduction<br />

Francisco Morales 173<br />

3.2 Mexico<br />

Francisco Morales, Rafael Rivera-Bustamante,<br />

Rafael Sal<strong>in</strong>as Pérez, Ir<strong>in</strong>eo Torres-Pacheco, Raúl Díaz Plaza,<br />

Wilson Avilés Baeza <strong>and</strong> Genovevo Ramírez Jaramillo 177<br />

3.3 Guatemala<br />

Francisco Morales, Abelardo Viana, Margarita Palmieri,<br />

Mónica Orozco <strong>and</strong> René Ruano 188<br />

3.4 El Salvador<br />

Francisco Morales, Carlos Pérez, Priscila Henríquez,<br />

Re<strong>in</strong>a de Serrano, Leopoldo Serrano <strong>and</strong> Claudio Nunes 197<br />

3.5 Honduras<br />

Francisco Morales, María Mercedes Doyle, Rogerio Traban<strong>in</strong>o,<br />

Carol<strong>in</strong>a Nolasco, Elsa Barrientos, Luís Jara <strong>and</strong> Norman Escoto 204<br />

3.6 Nicaragua<br />

Francisco Morales, Alberto Sediles, Aurelio Llano <strong>and</strong><br />

Falguni Guharay 210<br />

3.7 Costa Rica<br />

Francisco Morales, Luko Hilje, Juan Vallejos, Guillermo Sibaja,<br />

Carlos Araya <strong>and</strong> Rodolfo Araya 217<br />

3.8 Panama<br />

Francisco Morales, Orencio Fernández <strong>and</strong> José Guerra 222<br />

3.9 Haiti<br />

Francisco Morales, Jackson Donis <strong>and</strong> Emmanuel Prophete 226<br />

3.10 Cuba<br />

Francisco Morales, Gloria González, Carlos Murguido,<br />

Ana Echemendía, Yol<strong>and</strong>a Martínez, Yenín Hernández,<br />

Benito Faure <strong>and</strong> María Chailloux 230<br />

3.11 Dom<strong>in</strong>ican Republic<br />

Francisco Morales, Emigdio Gómez, Augusto Villar <strong>and</strong><br />

Julio N<strong>in</strong> 237<br />

3.12 Reproductive Crop Hosts of Bemisia tabaci (Gennadius)<br />

<strong>in</strong> Lat<strong>in</strong> America <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> Caribbean<br />

Pamela K. Anderson, Avas Hamon, Pilar Hernández <strong>and</strong><br />

Jon Mart<strong>in</strong> 243<br />

v<br />

5

Chapter<br />

6<br />

Whiteflies <strong>and</strong> <strong>Whitefly</strong>-<strong>borne</strong> Viruses <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Tropics<br />

Page<br />

3.13 Us<strong>in</strong>g Molecular Techniques to Analyse <strong>Whitefly</strong> Species <strong>and</strong><br />

Biotypes <strong>in</strong> Lat<strong>in</strong> America<br />

Lee Calvert, Natalia Villarreal <strong>and</strong> Donald Frohlich 251<br />

3.14 Conclusions <strong>and</strong> Recommendations<br />

Francisco Morales 263<br />

SECTION FOUR<br />

Whiteflies as Pests of Annual Crops <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Tropical<br />

Highl<strong>and</strong>s of Lat<strong>in</strong> America<br />

4.1 Introduction<br />

César Cardona 269<br />

4.2 Colombia <strong>and</strong> Ecuador<br />

César Cardona, Aristóbulo López-Avila <strong>and</strong> Oswaldo Valarezo 274<br />

4.3 Insecticide Resistance <strong>in</strong> Colombia <strong>and</strong> Ecuador<br />

César Cardona, Francisco Rendón, Isaura Rodríguez <strong>and</strong><br />

Aristóbulo López-Avila 285<br />

4.4 Conclusions <strong>and</strong> Recommendations<br />

César Cardona, Aristóbulo López-Avila <strong>and</strong> Oswaldo Valarezo 295<br />

SECTION FIVE<br />

Special Topics on Pest <strong>and</strong> Disease Management<br />

5.1 Susta<strong>in</strong>able Integrated Management of Whiteflies through<br />

Host Plant Resistance<br />

Anthony Bellotti, Joseph Tohme, Michael Dunbier <strong>and</strong><br />

Gail Timmerman 303<br />

5.2 Biological Control of Whiteflies by Indigenous Natural Enemies<br />

for Major Food Crops <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Neo<strong>tropics</strong><br />

Anthony Bellotti, Jorge Peña, Bernardo Arias,<br />

José María Guerrero, Harold Trujillo, Claudia Holguín <strong>and</strong><br />

Adriana Ortega 313<br />

5.3 Progress of Cassava Mosaic Disease <strong>in</strong> Ug<strong>and</strong>an Cassava<br />

Varieties <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong> Varietal Mixtures<br />

William Sserubombwe, Michael Thresh, James Legg <strong>and</strong><br />

William Otim-Nape 324<br />

5.4 Management of <strong>the</strong> Cassava Mosaic Disease P<strong>and</strong>emic <strong>in</strong><br />

East Africa<br />

James Legg, James Whyte, Reg<strong>in</strong>a Kap<strong>in</strong>ga <strong>and</strong> James Teri 332<br />

Conclusions<br />

Francisco Morales 339<br />

Acronyms <strong>and</strong> Abbreviations 345<br />

vi

Foreword<br />

This book is <strong>the</strong> product of <strong>the</strong><br />

collective knowledge accumulated over<br />

3 decades by hundreds of agricultural<br />

professionals <strong>and</strong> scientists <strong>in</strong>volved <strong>in</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> fight aga<strong>in</strong>st two of <strong>the</strong> worst pests<br />

of all times: whiteflies <strong>and</strong> <strong>whitefly</strong>transmitted<br />

<strong>viruses</strong>. Millions of farmers<br />

affected by <strong>the</strong>se pests have also<br />

contributed a great deal of valuable<br />

<strong>in</strong>formation regard<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> nature of <strong>the</strong><br />

problem <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> extent of <strong>the</strong> damage<br />

caused by <strong>the</strong>se pests <strong>in</strong> important<br />

food <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>dustrial crops. Examples of<br />

such are: cassava (Manihot esculenta<br />

Crantz), common bean (Phaseolus<br />

vulgaris L.), sweetpotato (Ipomoea<br />

batatas [L.] Lam.), lima bean<br />

(Phaseolus lunatus L. var. lunatus),<br />

mung bean (Vigna radiata [L.]<br />

R. Wilczek), tomato (Lycopersicon<br />

esculentum Mill.), peppers (Capsicum<br />

spp. L.), squash (Cucurbita moschata<br />

Duchesne), melon (Cucumis melo L.),<br />

o<strong>the</strong>r cucurbits, cotton (Gossypium<br />

hirsutum L.), tobacco (Nicotiana<br />

tabacum L.), soybean (Glyc<strong>in</strong>e max [L.]<br />

Merr.), lettuce (Lactuca sativa L. var.<br />

capitata L.) <strong>and</strong> eggplant (Solanum<br />

melongena L.).<br />

The devastat<strong>in</strong>g capacity of <strong>the</strong>se<br />

pests, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir global distribution <strong>in</strong><br />

* Former coord<strong>in</strong>ator for Phase 1 of <strong>the</strong><br />

Tropical <strong>Whitefly</strong> IPM Project; currently<br />

Research Director at <strong>the</strong> Centro<br />

Internacional de la Papa (CIP), Lima, Peru.<br />

vii<br />

Pamela Anderson*<br />

<strong>the</strong> ma<strong>in</strong> tropical <strong>and</strong> sub-tropical<br />

regions of <strong>the</strong> world, has been a major<br />

challenge to agricultural scientists <strong>in</strong><br />

both develop<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>dustrialized<br />

nations. Obviously, <strong>the</strong>ir impact has<br />

been far greater <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> rural areas of<br />

develop<strong>in</strong>g countries, where resourcepoor<br />

farmers have lost both traditional<br />

food crops (e.g., common bean <strong>and</strong><br />

cassava) <strong>and</strong> cash crops (e.g., tomato<br />

<strong>and</strong> peppers) to <strong>the</strong>se pests. Most of <strong>the</strong><br />

national agricultural research <strong>in</strong>stitutes<br />

<strong>and</strong> m<strong>in</strong>istries of agriculture <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

develop<strong>in</strong>g countries affected by <strong>the</strong>se<br />

pests have implemented different<br />

<strong>whitefly</strong> control measures, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g<br />

legal measures, which constitute a<br />

unique event <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> history of most<br />

develop<strong>in</strong>g countries where agriculture<br />

<strong>in</strong> general is not regulated by <strong>the</strong> state.<br />

The research activities described <strong>in</strong><br />

this book provide a general view of <strong>the</strong><br />

problem for agricultural scientists <strong>and</strong><br />

laypeople alike, <strong>and</strong> contributes a great<br />

deal of pert<strong>in</strong>ent <strong>in</strong>formation on <strong>the</strong><br />

nature <strong>and</strong> management of <strong>the</strong> problem<br />

<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> different crops affected by<br />

whiteflies <strong>and</strong> <strong>whitefly</strong>-transmitted<br />

<strong>viruses</strong>. In do<strong>in</strong>g so, <strong>the</strong> Tropical<br />

<strong>Whitefly</strong> Integrated Pest Management<br />

Project (TWF-IPM) has paid considerable<br />

attention to agricultural susta<strong>in</strong>ability,<br />

ecosystem health <strong>and</strong> human health<br />

issues, related to <strong>the</strong> appall<strong>in</strong>g misuse<br />

of highly toxic pesticides associated with<br />

<strong>whitefly</strong> control practices <strong>in</strong> develop<strong>in</strong>g<br />

countries.

The <strong>in</strong>formation conta<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

follow<strong>in</strong>g chapters will form <strong>the</strong> basis of<br />

a worldwide effort aimed at<br />

dissem<strong>in</strong>at<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> knowledge<br />

accumulated on <strong>the</strong> nature of <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>whitefly</strong>/virus problems <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> most<br />

efficient <strong>in</strong>tegrated pest <strong>and</strong> disease<br />

management measures available to<br />

develop susta<strong>in</strong>able mixed cropp<strong>in</strong>g<br />

8<br />

viii<br />

Whiteflies <strong>and</strong> <strong>Whitefly</strong>-<strong>borne</strong> Viruses <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Tropics<br />

systems. Moreover, this knowledge<br />

should ultimately contribute to improve<br />

<strong>the</strong> livelihoods of resource-poor farmers<br />

affected by <strong>the</strong>se pests throughout <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>tropics</strong>, by safeguard<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong>ir food<br />

staples <strong>and</strong> high-value crops, reduc<strong>in</strong>g<br />

production costs <strong>and</strong> pesticide<br />

contam<strong>in</strong>ation, <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

family <strong>in</strong>come.

Introduction<br />

Introduction<br />

The Problem of Whiteflies<br />

<strong>and</strong> <strong>Whitefly</strong>-Transmitted<br />

Viruses <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Tropics<br />

Although Mound <strong>and</strong> Halsey (1978)<br />

catalogued 1156 species of whiteflies<br />

(Homoptera: Aleyrodidae), only a<br />

limited number of <strong>whitefly</strong> species are<br />

considered pests of economic<br />

importance. Two <strong>whitefly</strong> species are<br />

key pests throughout <strong>the</strong> <strong>tropics</strong>:<br />

Bemisia tabaci (Gennadius) <strong>and</strong><br />

Trialeurodes vaporariorum (Westwood).<br />

Five additional <strong>whitefly</strong> species are<br />

considered as important pests <strong>in</strong><br />

specific regions: Aleurotrachelus socialis<br />

(Bondar), Trialeurodes variabilis<br />

(Qua<strong>in</strong>tance), Bemisia tuberculata<br />

(Bondar), Trialeurodes abutiloneus<br />

(Haldman) <strong>and</strong> Aleurocanthus woglumi<br />

(Ashby).<br />

Whiteflies are phloem (sap) feeders.<br />

They cause direct damage <strong>in</strong> some<br />

hosts by extract<strong>in</strong>g large quantities of<br />

sap. The honeydew that <strong>the</strong>y excrete,<br />

as a result of <strong>the</strong> copious sap <strong>in</strong>take,<br />

serves as substrate for sooty mould<br />

fungi, which can also damage hosts by<br />

block<strong>in</strong>g photosyn<strong>the</strong>sis. Sooty mould<br />

can discolour harvestable fruits <strong>and</strong><br />

fibre, affect<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> quality of produce,<br />

<strong>and</strong> can cause plant death <strong>in</strong> crops<br />

* Former coord<strong>in</strong>ator for Phase 1 of <strong>the</strong><br />

Tropical <strong>Whitefly</strong> IPM Project; currently<br />

Research Director at <strong>the</strong> Centro<br />

Internacional de la Papa (CIP), Lima, Peru.<br />

Pamela K. Anderson*<br />

such as potato (Solanum tuberosum L.),<br />

tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum Mill.)<br />

<strong>and</strong> common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris<br />

L.). In addition, B. tabaci is a vector of<br />

plant begomo<strong>viruses</strong> (Gem<strong>in</strong>iviridae:<br />

Begomovirus). These <strong>whitefly</strong>transmitted<br />

<strong>viruses</strong> (WTVs) are among<br />

<strong>the</strong> most destructive plant <strong>viruses</strong>;<br />

early virus <strong>in</strong>fection often results <strong>in</strong><br />

total crop loss.<br />

Although <strong>the</strong> problems caused by<br />

B. tabaci, both as pest <strong>and</strong> vector, have<br />

been recognized for more than<br />

100 years, serious damage had been<br />

limited to a h<strong>and</strong>ful of crops <strong>in</strong><br />

particular geographic areas. This<br />

scenario has changed over <strong>the</strong> past<br />

2 decades. The known WTVs have<br />

extended <strong>the</strong>ir geographic range <strong>and</strong><br />

o<strong>the</strong>r WTVs are emerg<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> new crops<br />

<strong>and</strong> geographic zones, globally.<br />

<strong>Whitefly</strong> <strong>in</strong>festations now have become<br />

severe <strong>in</strong> both traditional <strong>and</strong> nontraditional<br />

food <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>dustrial crops<br />

throughout <strong>the</strong> <strong>tropics</strong>.<br />

In Africa, cassava mosaic disease<br />

(CMD) was first described <strong>in</strong> 1894 from<br />

Tanzania (Warburg, 1894). In East<br />

Africa, <strong>the</strong> disease was not reported to<br />

cause serious losses until <strong>the</strong> 1920s. In<br />

West Africa, it was first recorded <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

coastal areas of Nigeria, Sierra Leone<br />

<strong>and</strong> Ghana <strong>in</strong> 1929 <strong>and</strong> had spread<br />

northward by 1945. By 1987, CMD had<br />

been reported from all countries <strong>in</strong><br />

Africa produc<strong>in</strong>g cassava (Manihot<br />

1

esculenta Crantz) (Fauquet <strong>and</strong><br />

Fargette, 1990). The disease had been<br />

caused by African cassava mosaic virus<br />

(ACMV) <strong>in</strong> South Africa <strong>and</strong> Africa west<br />

of <strong>the</strong> Rift Valley, <strong>and</strong> by East African<br />

cassava mosaic virus (EACMV) <strong>in</strong><br />

Madagascar <strong>and</strong> Africa east of <strong>the</strong> Rift<br />

Valley (Hong et al., 1993; Swanson <strong>and</strong><br />

Harrison, 1994). ACMV <strong>and</strong> EACMV are<br />

both B. tabaci-transmitted<br />

begomo<strong>viruses</strong>.<br />

In 1988, an extremely severe form<br />

of CMD was reported from nor<strong>the</strong>astern<br />

Ug<strong>and</strong>a. Infected cassava<br />

plants showed severe disease symptoms<br />

<strong>and</strong> produced little or no yield. The<br />

epidemic caused total crop failure <strong>in</strong><br />

north-eastern Ug<strong>and</strong>a (Otim-Nape et<br />

al., 1997). Each year s<strong>in</strong>ce 1988, <strong>the</strong><br />

epidemic moved progressively<br />

southwards along a broad front at a<br />

rate of approximately 20 km per year<br />

(Otim-Nape et al., 2000). By 1995, <strong>the</strong><br />

epidemic had reached Kenya (Otim-<br />

Nape et al., 2000), with losses<br />

estimated at 140,000 tons of cassava<br />

per year, conservatively worth<br />

US$14 million (Legg, 1999). The severe<br />

outbreak <strong>in</strong> Ug<strong>and</strong>a <strong>and</strong> neighbour<strong>in</strong>g<br />

countries has been associated with a<br />

novel recomb<strong>in</strong>ant (EACMV+ACMV)<br />

begomovirus, currently recognized as<br />

EACMV-Ug (Pita et al., 2001).<br />

Soon after, Lat<strong>in</strong> America was<br />

struggl<strong>in</strong>g with Bemisia-transmitted<br />

bean <strong>and</strong> tomato <strong>viruses</strong>. Bean golden<br />

mosaic virus (BGMV) was first described<br />

<strong>in</strong> Brazil <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> early 1960s as a m<strong>in</strong>or<br />

disease (5%-10% <strong>in</strong>cidence) of common<br />

bean <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> state of São Paulo (Costa,<br />

1965). S<strong>in</strong>ce <strong>the</strong>n, BGMV has become a<br />

widespread problem <strong>in</strong> Brazil <strong>and</strong> now<br />

is known to cause epidemics <strong>in</strong> northwestern<br />

Argent<strong>in</strong>a <strong>and</strong> eastern Bolivia.<br />

Simultaneously, ano<strong>the</strong>r begomovirus,<br />

Bean golden yellow mosaic virus<br />

(BGYMV), which causes similar<br />

symptoms, was ravag<strong>in</strong>g common bean<br />

production <strong>in</strong> over 12 countries of<br />

2<br />

Whiteflies <strong>and</strong> <strong>Whitefly</strong>-<strong>borne</strong> Viruses <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Tropics<br />

Central America <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> Caribbean<br />

(Morales, 1994). Yield loss from ei<strong>the</strong>r<br />

BGMV or BGYMV is often 100%<br />

because of <strong>the</strong> high <strong>in</strong>cidence of flower<br />

abortion <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> malformation of pods<br />

<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>fected plants (Morales <strong>and</strong><br />

Niessen, 1988). BGMV <strong>and</strong> BGYMV are<br />

considered to be <strong>the</strong> limit<strong>in</strong>g biotic<br />

constra<strong>in</strong>t to bean production <strong>in</strong> Lat<strong>in</strong><br />

America (Gálvez <strong>and</strong> Morales, 1989).<br />

Then, <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> late 1980s, tomatoproduc<strong>in</strong>g<br />

areas <strong>in</strong> Lat<strong>in</strong> America <strong>and</strong><br />

across <strong>the</strong> <strong>tropics</strong> began to suffer from<br />

high <strong>in</strong>cidences of <strong>whitefly</strong>-<strong>borne</strong><br />

begomo<strong>viruses</strong> with devastat<strong>in</strong>g<br />

economic consequences. While no<br />

formal assessment studies of crop loss<br />

had been undertaken for <strong>the</strong> tomato<br />

diseases caused by begomo<strong>viruses</strong>, <strong>the</strong><br />

empirical data were impressive. One of<br />

<strong>the</strong> more complete data sets came from<br />

<strong>the</strong> Dom<strong>in</strong>ican Republic (Polston <strong>and</strong><br />

Anderson, 1997). In 1988, multiple<br />

begomo<strong>viruses</strong> began to affect tomato<br />

production <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Dom<strong>in</strong>ican Republic.<br />

Crop damage from 1988 to 1995<br />

ranged from 5% to 95%. Economic<br />

losses <strong>in</strong> 1988 were estimated at<br />

US$10 million dollars, with losses from<br />

1989 to 1995 totall<strong>in</strong>g an estimated<br />

US$50 million dollars.<br />

These scenarios were be<strong>in</strong>g<br />

repeated across <strong>the</strong> <strong>tropics</strong>, with<br />

significant consequences to food<br />

security <strong>and</strong> poverty alleviation efforts<br />

as well as human <strong>and</strong> ecosystem<br />

health.<br />

Food security<br />

In Africa, cassava is one of <strong>the</strong> most<br />

widely grown staple crops <strong>and</strong> second<br />

only to maize (Zea mays L.) <strong>in</strong> terms of<br />

calorie <strong>in</strong>take <strong>in</strong> sub-Saharan Africa.<br />

About 200 million people, or 40% of<br />

<strong>the</strong> sub-Saharan Africa population, rely<br />

on cassava for <strong>the</strong>ir well-be<strong>in</strong>g. In some<br />

countries, people derive approximately<br />

1000 calories a day, or 50% of daily<br />

food <strong>in</strong>take, from cassava (IITA, 1988).

Introduction<br />

In addition to <strong>the</strong> yield losses<br />

caused by CMD, an estimated<br />

150,000 ha of cassava-grow<strong>in</strong>g l<strong>and</strong><br />

was ab<strong>and</strong>oned <strong>in</strong> Ug<strong>and</strong>a dur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong><br />

height of <strong>the</strong> epidemic; that is,<br />

equivalent to over 2.2 million metric<br />

tons (US$440 million). This caused<br />

food shortages <strong>and</strong> fam<strong>in</strong>e <strong>in</strong> a number<br />

of districts, particularly <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> eastern<br />

<strong>and</strong> nor<strong>the</strong>rn regions where <strong>the</strong> crop<br />

was <strong>the</strong> pr<strong>in</strong>ciple staple food (Otim-<br />

Nape, 1997).<br />

In Lat<strong>in</strong> America, common bean is<br />

one of <strong>the</strong> ma<strong>in</strong> staple foods,<br />

particularly among <strong>the</strong> rural <strong>and</strong> urban<br />

poor. In Central America, beans are <strong>the</strong><br />

most important source of prote<strong>in</strong>,<br />

usually be<strong>in</strong>g consumed three times a<br />

day. Central America, despite its small<br />

area (498,368 km 2 ), devotes twice as<br />

much of its geographical area to <strong>the</strong><br />

cultivation of beans (735,00 ha), when<br />

compared to major bean producers<br />

such as Brazil (>5,000,000 ha). Beans<br />

also are produced <strong>in</strong> some Caribbean<br />

isl<strong>and</strong>s, such as Cuba (26,000 t), <strong>the</strong><br />

Dom<strong>in</strong>ican Republic (55,000 t) <strong>and</strong><br />

Haiti (56,000 t) where <strong>the</strong>y play an<br />

important nutritional role <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> diet of<br />

<strong>the</strong> lower socio-economic classes.<br />

Smallhold<strong>in</strong>gs cultivated by farmers<br />

with limited resources are<br />

characteristic of bean production <strong>in</strong><br />

Central America <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> Caribbean. In<br />

El Salvador, for <strong>in</strong>stance, 85% of <strong>the</strong><br />

bean producers cultivate less than<br />

14 ha, <strong>and</strong> 50% of <strong>the</strong>se producers<br />

have hold<strong>in</strong>gs of less than 3.5 ha.<br />

Despite <strong>the</strong> large area planted to<br />

beans <strong>in</strong> Central America, average<br />

productivity is low (495 kg/ha)<br />

compared to <strong>the</strong> average yield expected<br />

(over 1500 kg/ha) <strong>in</strong> most beanproduc<strong>in</strong>g<br />

regions of <strong>the</strong> USA <strong>and</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

temperate countries <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> world. The<br />

ma<strong>in</strong> factor identified as responsible for<br />

<strong>the</strong> low bean productivity <strong>in</strong> Lat<strong>in</strong><br />

America has been <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>cidence of<br />

biotic constra<strong>in</strong>ts, particularly<br />

diseases. Morales (1992) estimated that<br />

by <strong>the</strong> early 1990s, approximately<br />

2,500,000 ha were under attack by<br />

BGMV/BGYMV <strong>and</strong> that at least<br />

1 million additional hectares could not<br />

be planted to beans each year because<br />

of <strong>the</strong> possibility of total yield losses,<br />

ma<strong>in</strong>ly dur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> dry seasons, when<br />

<strong>whitefly</strong> populations peak. Throughout<br />

Central America <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> Caribbean<br />

Bas<strong>in</strong>, figures for crop damage<br />

<strong>in</strong>dicated that <strong>the</strong> BGYMV <strong>in</strong>fection was<br />

devastat<strong>in</strong>g. And <strong>the</strong>re was cont<strong>in</strong>u<strong>in</strong>g<br />

consensus that BGYMV was <strong>the</strong> major<br />

biotic factor limit<strong>in</strong>g bean production <strong>in</strong><br />

Lat<strong>in</strong> America (Morales, 1994).<br />

Poverty alleviation<br />

Many resource-poor producers <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>tropics</strong> modified <strong>the</strong>ir traditional<br />

cropp<strong>in</strong>g systems <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> 1980s, to<br />

<strong>in</strong>corporate non-traditional cash <strong>and</strong><br />

export crops. The shift from<br />

subsistence to commercial agriculture<br />

is an opportunity to alleviate poverty <strong>in</strong><br />

rural areas. Smallholder producers<br />

across <strong>the</strong> <strong>tropics</strong> have begun to<br />

cultivate cash crops such as tomato<br />

(Lycopersicon esculentum), pepper<br />

(Capsicum spp. L.), melon (Cucumis<br />

melo L.), watermelon (Citrullus lanatus<br />

[Thunb.] Matsum. & Nakai), squash<br />

(Cucurbita moschata Duchesne), grape<br />

(Vitis v<strong>in</strong>ifera L.), okra (Abelmoschus<br />

esculentus [L.] Moench), cucumber<br />

(Cucumis sativus L. var. sativus),<br />

cabbage (Brassica oleracea L.), eggplant<br />

(Solanum melongena L.), broccoli<br />

(Brassica oleracea L. var. italica Plenck)<br />

<strong>and</strong> ornamentals. However, most of<br />

<strong>the</strong>se horticultural crops are<br />

particularly susceptible to pests<br />

previously unknown to most smallscale<br />

farmers.<br />

In <strong>the</strong> absence of adequate<br />

technical assistance for small-scale<br />

farmers <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>tropics</strong>, <strong>the</strong> new pest<br />

problems were primarily dealt with by a<br />

myriad of pesticides applied<br />

<strong>in</strong>discrim<strong>in</strong>ately. To fur<strong>the</strong>r complicate<br />

3

this situation, a new biotype (B) of<br />

B. tabaci was <strong>in</strong>troduced <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

Americas <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> early 1990s. This<br />

biotype proved to be far more<br />

polyphagous <strong>and</strong> fecund that <strong>the</strong><br />

orig<strong>in</strong>al A biotype <strong>and</strong> has been an<br />

important factor <strong>in</strong> most of <strong>the</strong> major<br />

outbreaks of whiteflies <strong>and</strong> <strong>whitefly</strong><strong>borne</strong><br />

<strong>viruses</strong>. Dur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> past decade,<br />

<strong>the</strong> outbreak of <strong>whitefly</strong> pests <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

epidemics caused by <strong>whitefly</strong>transmitted<br />

begomo<strong>viruses</strong> <strong>in</strong> cash<br />

crops has been often devastat<strong>in</strong>g.<br />

Pesticide abuse is <strong>the</strong> norm <strong>in</strong> all<br />

<strong>whitefly</strong>-stricken regions of <strong>the</strong> <strong>tropics</strong>,<br />

which <strong>in</strong>creases production costs <strong>and</strong><br />

disqualifies contam<strong>in</strong>ated (pesticide<br />

residues) produce for export.<br />

At present, many of <strong>the</strong> small-scale<br />

farmers that attempted to diversify<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir cropp<strong>in</strong>g systems have failed to<br />

do so because of <strong>whitefly</strong>-associated<br />

problems. Prime agricultural l<strong>and</strong><br />

rema<strong>in</strong>s unexploited <strong>in</strong> many<br />

develop<strong>in</strong>g countries dur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> dry<br />

seasons, when <strong>whitefly</strong> populations<br />

peak, despite <strong>the</strong> availability of water<br />

(irrigation districts) <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>se areas. The<br />

welfare of develop<strong>in</strong>g countries <strong>and</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong>ir low-<strong>in</strong>come citizens is tightly<br />

l<strong>in</strong>ked to <strong>the</strong> existence of cash-earn<strong>in</strong>g<br />

commodities, pr<strong>in</strong>cipally agricultural<br />

products.<br />

The ma<strong>in</strong> force driv<strong>in</strong>g <strong>whitefly</strong><br />

outbreaks <strong>and</strong> crop losses due to<br />

<strong>whitefly</strong> attack <strong>and</strong> WTVs is <strong>the</strong> lack of<br />

qualified technical assistance to small<strong>and</strong><br />

medium-scale farmers <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>tropics</strong>. The Tropical <strong>Whitefly</strong><br />

Integrated Pest Management (TWF-IPM)<br />

Project is currently enter<strong>in</strong>g a f<strong>in</strong>al<br />

phase when most of <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>formation<br />

presented <strong>in</strong> this book <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> lessons<br />

learned dur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> validation of IPM<br />

practices <strong>in</strong> Phase II will be translated<br />

<strong>in</strong>to practical recommendations for<br />

resource-poor farmers throughout <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>tropics</strong>.<br />

4<br />

Whiteflies <strong>and</strong> <strong>Whitefly</strong>-<strong>borne</strong> Viruses <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Tropics<br />

Human <strong>and</strong> ecosystem health<br />

The reliance of farmers on<br />

agrochemicals to protect <strong>the</strong>ir cash<br />

crops aga<strong>in</strong>st <strong>whitefly</strong> pests <strong>and</strong><br />

<strong>whitefly</strong>-<strong>borne</strong> <strong>viruses</strong> has resulted <strong>in</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> systematic destruction of natural<br />

enemies that were once effective <strong>in</strong><br />

provid<strong>in</strong>g natural control, <strong>whitefly</strong><br />

populations with high levels of<br />

<strong>in</strong>secticide resistance <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> creation<br />

of new secondary pest problems. The<br />

rejection of contam<strong>in</strong>ated produce <strong>in</strong><br />

<strong>in</strong>ternational markets has led to <strong>the</strong><br />

sale of highly contam<strong>in</strong>ated food<br />

products <strong>in</strong> develop<strong>in</strong>g countries, with<br />

obvious detrimental health<br />

consequences for rural <strong>and</strong> urban<br />

consumers alike. Whiteflies provide a<br />

classic example of <strong>the</strong> pesticide<br />

treadmill. Insecticide abuse has<br />

become a serious threat to <strong>the</strong><br />

environment as well as a health hazard<br />

to producers <strong>and</strong> consumers.<br />

About 10% of <strong>the</strong> world’s<br />

population lives <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> ma<strong>in</strong> highl<strong>and</strong>s<br />

<strong>and</strong> mounta<strong>in</strong>ous areas of <strong>the</strong><br />

develop<strong>in</strong>g world (<strong>the</strong> Andes of South<br />

America, <strong>the</strong> Africa ranges <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

Himalayas). The management of<br />

resources <strong>in</strong> those ecosystems affects<br />

an additional 40% of <strong>the</strong> world’s<br />

population, which <strong>in</strong>habits adjacent<br />

areas such as Inter-Andean valleys <strong>in</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> Andean Zone. Traditionally, people<br />

<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> highl<strong>and</strong>s have been<br />

marg<strong>in</strong>alized from major development<br />

efforts, with significant repercussions<br />

on poverty, migration <strong>and</strong> social unrest<br />

as well as environmental deterioration<br />

<strong>in</strong> situ <strong>and</strong> downstream (IFPRI, 1995).<br />

One major issue regard<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong><br />

welfare of those liv<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> highl<strong>and</strong> areas<br />

of Lat<strong>in</strong> America is environmental<br />

degradation caused by excessive<br />

pesticide use. It is well known that<br />

pesticide consumption <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

develop<strong>in</strong>g world is <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g rapidly.<br />

It was thought <strong>in</strong>itially that <strong>in</strong>creases

Introduction<br />

<strong>in</strong> pesticide use <strong>in</strong> Lat<strong>in</strong> America were<br />

ma<strong>in</strong>ly due to <strong>the</strong> growth of plantation<br />

crops, an important source of export<br />

revenue (Bellotti et al., 1990). However,<br />

as po<strong>in</strong>ted out by Whitaker (1993), <strong>the</strong><br />

develop<strong>in</strong>g country share of <strong>the</strong> world<br />

agrochemical usage, currently valued<br />

at US$10.6 billion, was forecast to rise<br />

from 19% <strong>in</strong> 1988 to an estimated 35%<br />

by <strong>the</strong> year 2000. Much of this<br />

projected growth was attributed to a<br />

wider <strong>and</strong> more <strong>in</strong>tensive use of<br />

chemical protection by smallholder<br />

farmers. Unfortunately, highly toxic<br />

<strong>in</strong>secticides represent up to 45% of<br />

pesticide use <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> develop<strong>in</strong>g world.<br />

In <strong>the</strong> early 1980s, <strong>the</strong> greenhouse<br />

<strong>whitefly</strong>, Trialeurodes vaporariorum<br />

(Westwood), became a very serious pest<br />

of several hillside-grown crops <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

Andes. Major outbreaks occurred <strong>in</strong><br />

1987, 1991 <strong>and</strong> 1994 <strong>in</strong> selected areas<br />

of Colombia, nor<strong>the</strong>rn Ecuador <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

Constanza Valley <strong>in</strong> Dom<strong>in</strong>ican<br />

Republic. For example, <strong>in</strong>secticide use<br />

by small-scale bean farmers, which<br />

was negligible until 1975-77<br />

(Schoonhoven <strong>and</strong> Cardona, 1980), has<br />

<strong>in</strong>creased steadily <strong>and</strong> became<br />

excessive <strong>in</strong> Colombia <strong>and</strong> Ecuador.<br />

Surveys conducted <strong>in</strong> two regions of<br />

Colombia <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> nor<strong>the</strong>rn part of<br />

Ecuador (CIAT, 1994) revealed that<br />

100% of 893 farmers surveyed sprayed<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir crops <strong>in</strong> an attempt to control <strong>the</strong><br />

greenhouse <strong>whitefly</strong>. Highest<br />

<strong>in</strong>secticide use occurred <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

Sumapaz region of Colombia where<br />

farmers make an average of<br />

11.1 applications per season.<br />

Most alarm<strong>in</strong>g was <strong>the</strong> fact that<br />

some growers sprayed <strong>the</strong>ir crops up to<br />

24 times <strong>in</strong> a crop cycle of<br />

90-100 days, that is, every 3 to 4 days.<br />

Insecticide abuse on beans <strong>in</strong> Colombia<br />

(5.6 kg active <strong>in</strong>gredient per ha per<br />

season) could be compared to<br />

<strong>in</strong>secticide consumption for cotton<br />

(Gossypium hirsutum L.) (6.2 kg active<br />

<strong>in</strong>gredient per hectare per season), a<br />

crop that has been known traditionally<br />

as <strong>the</strong> worst offender <strong>in</strong> terms of<br />

<strong>in</strong>secticide use. And, of <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>secticides<br />

utilized for whiteflies, 78% were<br />

classified <strong>in</strong> toxicological category I<br />

(highly toxic) <strong>and</strong> most often applied <strong>in</strong><br />

mixture with o<strong>the</strong>r <strong>in</strong>secticides, broadspectrum<br />

fungicides <strong>and</strong> foliar<br />

fertilizers. Farmers usually did not take<br />

precautions when h<strong>and</strong>l<strong>in</strong>g pesticides;<br />

up to 24% of those surveyed admit that<br />

<strong>the</strong>y have been <strong>in</strong>toxicated at least<br />

once <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> prior 10 years (CIAT, 1994).<br />

In <strong>the</strong> east African highl<strong>and</strong>s, a<br />

contribut<strong>in</strong>g factor to environmental<br />

degradation was <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>discrim<strong>in</strong>ate<br />

<strong>and</strong>/or excessive use of broadspectrum<br />

<strong>in</strong>secticides as part of <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>in</strong>tensive crop protection system <strong>in</strong><br />

<strong>in</strong>dustrial crops, especially cotton, <strong>and</strong><br />

to some extent on plantation crops<br />

such as coffee (Coffea spp. L.) <strong>and</strong> tea<br />

(Camellia s<strong>in</strong>ensis [L.] Kuntze). The<br />

problems of pesticide resistance <strong>and</strong><br />

pest resurgence although <strong>in</strong>itially<br />

created on <strong>the</strong>se target crops had<br />

extended to <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r seasonal crops<br />

grown <strong>in</strong> rotation <strong>and</strong>/or comb<strong>in</strong>ation<br />

with <strong>the</strong> plantation crops, as <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

case of whiteflies.<br />

The <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g importance of<br />

horticultural production also brought<br />

with it <strong>the</strong> attendant strategy of<br />

pesticide-based protection <strong>in</strong> an effort<br />

to harvest damage-free produce.<br />

Intensive use of pesticides <strong>in</strong> vegetable<br />

crops had become quite common <strong>in</strong><br />

large areas of Sudan, Ug<strong>and</strong>a, Kenya,<br />

Tanzania <strong>and</strong> Zimbabwe. In a survey of<br />

vegetable farmers <strong>in</strong> Kenya it was<br />

found that <strong>the</strong> majority perceived that<br />

<strong>the</strong>y would lose up to 90% of <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

harvest if <strong>the</strong>y did not use pesticides.<br />

By <strong>the</strong> early 1990s, <strong>the</strong>se vegetable<br />

farmers were apply<strong>in</strong>g up to 19 sprays<br />

a season, with a significant proportion<br />

of farmers spray<strong>in</strong>g 9-12 times per<br />

season (KARI-GTZ, 1994). It was<br />

5

critical to beg<strong>in</strong> work <strong>in</strong> eastern Africa<br />

<strong>in</strong> hopes of <strong>in</strong>terven<strong>in</strong>g with alternative<br />

<strong>whitefly</strong> crop protection measures,<br />

before <strong>the</strong> <strong>whitefly</strong> pests <strong>and</strong> WTVs<br />

reach <strong>the</strong> severity witnessed <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

Neo<strong>tropics</strong>.<br />

There was an urgent need to<br />

develop IPM systems that would reduce<br />

pesticide use <strong>and</strong> help re-establish <strong>the</strong><br />

ecological equilibrium by means of<br />

non-chemical approaches to <strong>whitefly</strong><br />

management. For <strong>whitefly</strong> pests this<br />

implies identify<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> pr<strong>in</strong>cipal crop<br />

hosts, establish<strong>in</strong>g economic <strong>in</strong>jury<br />

levels (EILs) <strong>and</strong> develop<strong>in</strong>g new<br />

approaches to ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong> whiteflies<br />

below <strong>the</strong> EIL. For <strong>whitefly</strong> vectors,<br />

however, <strong>the</strong> traditional IPM approach<br />

will not suffice. Vectors must be<br />

studied <strong>and</strong> managed with<strong>in</strong> an<br />

epidemiological framework, that is,<br />

study <strong>and</strong> analysis of <strong>the</strong> WTV system<br />

with IPM <strong>in</strong>tervention strategies<br />

result<strong>in</strong>g from <strong>the</strong> epidemiological<br />

analysis.<br />

6<br />

Orig<strong>in</strong> <strong>and</strong> Organization<br />

of <strong>the</strong> CGIAR TWF-IPM<br />

Project<br />

The Systemwide Programme on<br />

Integrated Pest Management<br />

(SP-IPM)<br />

The Consultative Group for<br />

International Agricultural Research<br />

(CGIAR) consists of 15 International<br />

Agricultural Research Centres (IARCs)<br />

located around <strong>the</strong> world. Historically,<br />

each Centre has worked <strong>in</strong> a relatively<br />

<strong>in</strong>dependent <strong>and</strong> autonomous fashion.<br />

Dur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> 1990s, <strong>the</strong> CGIAR<br />

Secretariat recognized that significant<br />

benefits could be derived by pool<strong>in</strong>g<br />

human capital, <strong>in</strong>frastructure <strong>and</strong><br />

economic resources to jo<strong>in</strong>tly tackle<br />

research problems that numerous<br />

centres were work<strong>in</strong>g on<br />

<strong>in</strong>dependently. New <strong>in</strong>ter-centre<br />

Whiteflies <strong>and</strong> <strong>Whitefly</strong>-<strong>borne</strong> Viruses <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Tropics<br />

<strong>in</strong>itiatives <strong>in</strong>cluded <strong>the</strong> creation of <strong>the</strong><br />

SP-IPM. <strong>Whitefly</strong> <strong>and</strong> WTV research had<br />

been ongo<strong>in</strong>g at several of <strong>the</strong> IARCs<br />

s<strong>in</strong>ce <strong>the</strong> 1970s. Due to <strong>the</strong> grow<strong>in</strong>g<br />

importance of <strong>the</strong> <strong>whitefly</strong> <strong>and</strong> WTV<br />

problem, <strong>the</strong> TWF-IPM Project was <strong>the</strong><br />

first <strong>in</strong>ter-centre project approved<br />

with<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> new programme. The<br />

International Center for Tropical<br />

Agriculture (CIAT, <strong>the</strong> Spanish<br />

acronym) was designated as <strong>the</strong><br />

conven<strong>in</strong>g centre to organize <strong>the</strong> Inter-<br />

Centre <strong>Whitefly</strong> IPM Task Force <strong>and</strong> to<br />

formulate <strong>the</strong> Inter-Centre proposal on<br />

Susta<strong>in</strong>able Integrated Management of<br />

Whiteflies as Pests <strong>and</strong> Vectors of Plant<br />

Viruses <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Tropics (<strong>the</strong> CGIAR<br />

TWF-IPM Project).<br />

A Task Force Meet<strong>in</strong>g was held at<br />

CIAT <strong>in</strong> Cali, Colombia, from<br />

13-15 February 1996. The objectives of<br />

<strong>the</strong> meet<strong>in</strong>g were to discuss: (a) <strong>the</strong><br />

goal, purpose, outputs <strong>and</strong> activities<br />

that should be proposed for <strong>the</strong> project;<br />

<strong>and</strong> (b) a structure for <strong>the</strong> global<br />

<strong>Whitefly</strong> IPM project, as well as how to<br />

l<strong>in</strong>k <strong>and</strong> coord<strong>in</strong>ate <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>stitutions that<br />

would be <strong>in</strong>volved <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> project.<br />

The Task Force Meet<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>cluded<br />

24 participants represent<strong>in</strong>g IARCs,<br />

National Agricultural Research Systems<br />

(NARS) <strong>and</strong> Advanced Research<br />

Institutions (ARIs). After considerable<br />

discussion on <strong>the</strong> nature of <strong>the</strong> <strong>whitefly</strong><br />

problem, <strong>the</strong> Task Force agreed that it<br />

was possible to def<strong>in</strong>e three <strong>whitefly</strong><br />

problems that should be prioritized:<br />

(1) Whiteflies as vectors <strong>in</strong> mixed<br />

cropp<strong>in</strong>g systems <strong>in</strong> low to mid<br />

altitudes of <strong>the</strong> <strong>tropics</strong>;<br />

(2) Whiteflies as pests <strong>in</strong> mixed<br />

cropp<strong>in</strong>g systems <strong>in</strong> tropical<br />

highl<strong>and</strong>s; <strong>and</strong><br />

(3) Whiteflies as vectors <strong>and</strong> pests of<br />

<strong>the</strong> semi-perennial cassava.<br />

The first problem focused on<br />

whiteflies as vectors of plant <strong>viruses</strong> <strong>in</strong>

Introduction<br />

annual crops, especially legumes <strong>and</strong><br />

vegetables, <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> tropical lowl<strong>and</strong>s.<br />

The second problem focused on<br />

whiteflies as direct pests <strong>in</strong> annual<br />

crops <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> highl<strong>and</strong>s. And <strong>the</strong> third<br />

problem focused on <strong>whitefly</strong> pests <strong>and</strong><br />

vectors <strong>in</strong> a semi-perennial crop,<br />

cassava.<br />

Based on <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>itial <strong>Whitefly</strong> IPM<br />

Task Force Meet<strong>in</strong>g, <strong>and</strong> with<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> CG<br />

framework for an eco-regional problem<br />

approach (Bouma et al., 1995), <strong>the</strong><br />

project was structured <strong>in</strong>to six subprojects:<br />

(1) Bemisia tabaci as a virus vector <strong>in</strong><br />

cassava <strong>and</strong> sweet potato <strong>in</strong> sub-<br />

Saharan Africa – led by IITA;<br />

(2) Bemisia tabaci as a virus vector <strong>in</strong><br />

mixed cropp<strong>in</strong>g systems of <strong>the</strong><br />

Caribbean, Mexico <strong>and</strong> Central<br />

America – led by CIAT;<br />

(3) Bemisia tabaci as a virus vector <strong>in</strong><br />

mixed cropp<strong>in</strong>g systems of Eastern<br />

<strong>and</strong> Sou<strong>the</strong>rn Africa – led by <strong>the</strong><br />

International Centre of Insect<br />

Physiology <strong>and</strong> Ecology (ICIPE);<br />

(4) Bemisia tabaci as a virus vector <strong>in</strong><br />

mixed cropp<strong>in</strong>g systems of S.E.<br />

Asia – led by <strong>the</strong> Asian Vegetable<br />

Research <strong>and</strong> Development Center<br />

(AVRDC);<br />

(5) Trialeurodes vaporariorum as a<br />

direct pest <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> tropical<br />

highl<strong>and</strong>s of Lat<strong>in</strong> America – led by<br />

CIAT; <strong>and</strong><br />

(6) Whiteflies as direct pests on<br />

cassava <strong>in</strong> South America – led by<br />

CIAT.<br />

There was consensus by <strong>the</strong> Task<br />

Force on <strong>the</strong> project goal, project<br />

purpose <strong>and</strong> project outputs for <strong>the</strong><br />

TWF-IPM project. The project goal is to<br />

improve liv<strong>in</strong>g conditions of rural<br />

families through <strong>the</strong> effective<br />

management of whiteflies, result<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong><br />

<strong>in</strong>creased crop production <strong>and</strong> a safer<br />

environment. The project purpose is to<br />

reduce crop losses due to <strong>whitefly</strong><br />

feed<strong>in</strong>g damage <strong>and</strong> WTVs. The Task<br />

Force agreed to organize <strong>the</strong> project<br />

around six outputs:<br />

(1) Formation of an <strong>in</strong>ternational<br />

network for research on whiteflies<br />

<strong>and</strong> WTVs <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>tropics</strong>;<br />

(2) Characterization of <strong>whitefly</strong><br />

problems <strong>in</strong> order to prioritize<br />

critical target areas;<br />

(3) Improvement of <strong>the</strong> underst<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g<br />

of <strong>whitefly</strong> pest <strong>and</strong> disease<br />

dynamics <strong>in</strong> critical target areas;<br />

(4) Development <strong>and</strong> test<strong>in</strong>g of IPM<br />

strategies <strong>and</strong> tactics;<br />

(5) Streng<strong>the</strong>n<strong>in</strong>g of NARS research<br />

capacity, policy formulation <strong>and</strong><br />

IPM implementation; <strong>and</strong><br />

(6) Assessment of project impact.<br />

Phase 1 of <strong>the</strong> CGIAR TWF-IPM<br />

Project<br />

The project was conceptualized <strong>in</strong> three<br />

phases, to be carried out over 10 years.<br />

Phase 1 of <strong>the</strong> project would focus<br />

primarily on Output 1 (network<br />

formation) <strong>and</strong> Output 2 (problem<br />

characterization) as <strong>the</strong> basis for<br />

Phase 2 work, with limited activities <strong>in</strong><br />

Output 3 (pest <strong>and</strong> disease dynamics)<br />