FASHION-DETECTIVE

FASHION-DETECTIVE

FASHION-DETECTIVE

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Danielle Whitfield

Contents<br />

Foreword 1<br />

Introduction 2<br />

Examination report: 13<br />

The case of the fake Worth<br />

by Annette Soumilas<br />

Short story: 17<br />

The real McCoy<br />

by Garry Disher<br />

Examination report: 21<br />

The case of the poisonous pigment<br />

by Bronwyn Cosgrove<br />

Short story: 24<br />

The bequest<br />

by Sulari Gentill<br />

Examination report: 27<br />

The secret in the doll’s dress<br />

by Kate Douglas<br />

Short story: 31<br />

Paper piecing<br />

by Lili Wilkinson<br />

Examination report: 35<br />

The case of the fraudulent fur<br />

by Kate Douglas<br />

Short story: 39<br />

Escape from Grantchester Manor<br />

by Kerry Greenwood<br />

List of works 43

Foreword<br />

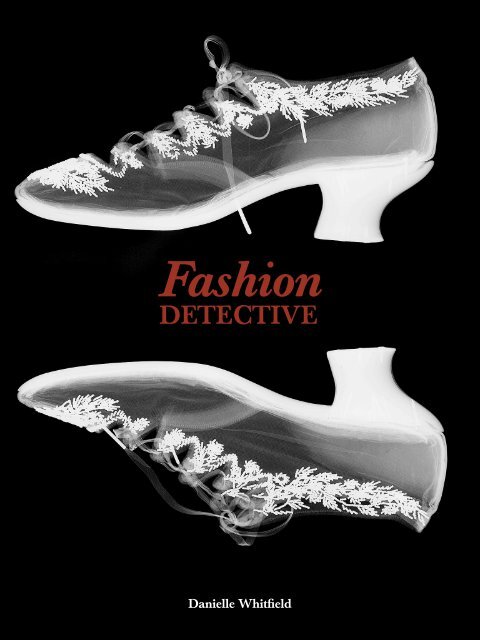

Fashion Detective is an exhibition that heralds an innovative new approach to<br />

the interpretation and display of fashion and textiles at the National Gallery of<br />

Victoria. A departure from the usual conventions of chronology, artistry and<br />

technique, Fashion Detective is instead a set of investigations that challenge us to<br />

reappraise what we see and know.<br />

The exhibition takes a large number of unattributed nineteenth-century<br />

garments and accessories from the NGV’s collection as the basis for a series<br />

of ‘cases’. Encountered as small vignettes, these cases tell different stories of analysis<br />

and deduction, and present alternate ways of reading fashion. Some rely on objectbased<br />

study and forensics to reach conclusions; others are purposefully speculative.<br />

It is always pleasing to see contemporary artists engage with the NGV collection in<br />

creative ways, and Fashion Detective introduces a new model for this. By inviting four<br />

leading Australian crime writers to create short stories based upon the works on<br />

display, the exhibition explores the mysteries of our collection in surprising ways.<br />

Melbourne has always had a strong affinity with crime fiction, and it is great to see<br />

current exponents of the genre bring their rich imaginations to this project.<br />

This publication brings together the many investigative layers which inform<br />

Fashion Detective. Elucidating the curatorial rationale behind the exhibition,<br />

here forensics and fiction are presented as a two-fold encounter with the objects<br />

on display. While succinct case studies by the Gallery’s Textile Conservation team<br />

provide fascinating insight into the scientific nature of conservation work and what<br />

is revealed by close examination, the four specially commissioned crime fictions<br />

introduce narrative possibilities that speak to our interest in the social life<br />

of clothing.<br />

I extend particular thanks to authors Garry Disher, Kerry Greenwood, Sulari<br />

Gentill and Lili Wilkinson for their inspired responses to this project. I also offer<br />

thanks to the exhibition curator, Danielle Whitfield, and the Textile Conservation<br />

team led by Bronwyn Cosgrove, as well as to the entire NGV staff involved in<br />

bringing this exhibition and publication to life. I am delighted to see such creative<br />

collaboration and invite you to enjoy this unique approach and the many mysteries<br />

it explores.<br />

Tony Ellwood<br />

Director, National Gallery of Victoria

Introduction<br />

Never trust to general impressions,<br />

my boy, but concentrate yourself upon details.<br />

Sherlock Holmes, A Case of Identity (1892)<br />

Danielle Whitfield<br />

2

Introduction<br />

Danielle Whitfield<br />

You see, but you do not observe.<br />

The distinction is clear.<br />

Sherlock Holmes, The Scandal in Bohemia (1892)<br />

ny gallery archive contains a large number of works that<br />

remain unattributed – ‘makers unknown’. Anonymous<br />

and often inscrutable, these objects have the capacity<br />

to excite our curiosity at a time when the world is<br />

besieged by brands and logos. Within fashion especially,<br />

the contrast between today’s superstar couturiers and the nameless<br />

dressmakers and tailors of earlier centuries could not be greater.<br />

Fashion Detective takes a selection of miscellaneous nineteenth-century<br />

garments and accessories from the National Gallery of Victoria’s<br />

collection as the starting point for a series of investigations. Using<br />

material evidence, forensics and newly commissioned fictions as<br />

alternate interpretative strategies, the exhibition is an encounter with<br />

the art of detection.<br />

Taking its cue from tropes of Victorian crime fiction, Fashion Detective<br />

is divided into a series of ‘cases’ that present the visitor with<br />

different investigative paths and narrative opportunities. From fakes<br />

and forgeries to poisonous dyes, concealed clues and mysterious<br />

marks to missing persons, the exhibition places objects under close<br />

examination. Each case follows a specific course of analysis that<br />

encourages thinking differently about what we see and what<br />

we know.<br />

Fashion Detective is not intended as a comprehensive study of<br />

nineteenth-century dress. Rather, it is an exhibition about modes of<br />

investigation; about leads, encounters, discoveries, stories, science<br />

and speculation. It is about the detective work that curators and<br />

conservators undertake, and what this can reveal. Ultimately it is<br />

about questions – many of which will never be answered.<br />

Reading fashion<br />

Never trust to general impressions, my boy, but<br />

concentrate yourself upon details.<br />

Sherlock Holmes, A Case of Identity (1892)<br />

Learning how to ‘read’ a dress has been an important concern for<br />

fashion studies scholars in recent years. Drawing on the work of art<br />

historian Jules Prown, Valerie Steele, Director and Chief Curator<br />

of the Museum at the Fashion Institute of Technology, New York,<br />

describes the process as involving three stages: description, deduction<br />

and speculation. 1<br />

The description stage records the physical characteristics and features<br />

of a garment, including its measurements, medium, construction<br />

details, style, colour, texture, use and wear. It establishes whether<br />

or not an object is complete, whether it has been altered or repaired<br />

and flags questions about authenticity. The deduction stage involves<br />

reflection on the sensory interaction between ‘object and the<br />

perceiver’. 2 It considers the garment in terms of how it would have<br />

been worn, what it might feel like to wear, what it reveals about the<br />

wearer’s taste or social status and how it compares to other examples.<br />

The speculation stage involves ‘framing [a] hypothesis and questions’<br />

for testing against external evidence. These questions in turn drive<br />

specific paths of research. 3<br />

Fashion and forgery<br />

I’d be more worried if my product<br />

wasn’t being copied.<br />

Miuccia Prada 4<br />

Unknown (France), Bodice, c.1885 (label detail)<br />

The central question in ‘The case of the fake Worth’ is about<br />

attribution: is the labelled Bodice, c.1885, a fake couture garment?<br />

Is the label a forgery? While the answer is more complex than a<br />

simple yes or no, detailed object-based analysis was essential to the<br />

conclusion. Clues gleaned from the garment’s construction (stitching,<br />

pattern pieces, boning, finishing techniques, alterations, labelling and<br />

fabric choice), stylistic analysis (knowledge of the designer’s oeuvre)<br />

and historical research all formed part of the material evidence.<br />

Mary Richardson, Sampler, 1783<br />

3

complex and linked to different historical modes of circulation and<br />

exchange, not least its acquisition by the NGV in 1963.<br />

Knowing whether or not something is a forgery forever changes<br />

the way we look at it, but learning to tell the difference between an<br />

original and a copy is, as Nelson Goodman famously argued, a matter<br />

of learning how to perceive. 9<br />

Fashion and forensics<br />

C27H25N4(SO)01/2<br />

Chemical composition of Perkin’s mauve<br />

(left) François Pinet, Paris (shoemaker), Jean-Louis François Pinet (designer) Boots 1867<br />

(right) Pair of authentic Pinet shoes exhibited by S.D. & L.A. Tallerman in Sydney, 1878<br />

Counterfeiting was rife in the latter part of the nineteenth century.<br />

In 1896 Georges Vuitton, son of Louis Vuitton, designed and<br />

registered the house monogram – a pattern of interlocking LVs<br />

interspersed with quatrefoils and flowers – in response to the<br />

counterfeiting of their bespoke travel goods. Similarly, in September<br />

1878 celebrated Parisian shoe designer Jean-Louis François Pinet<br />

engaged retailers Samuel D. and Lewis A. Tallerman (of London and<br />

Melbourne) as:<br />

His sole agents for the New Zealand and Australian colonies<br />

[after] having received information that the name and brand of his<br />

house [was] being fraudulently used and placed upon boots and<br />

shoes of low price and inferior description. 5<br />

Today, fashion fakes present an even bigger problem. Luxury brands<br />

are among the most counterfeited products. In 2013 the counterfeit<br />

goods industry accounted for two per cent of the world trade. 6<br />

For Sherlock Holmes, the great nineteenth-century literary detective,<br />

acuity, intelligence and the aura of scientific enquiry were the factors by which<br />

he decoded evidence – be it a watch, hat, stick or the appearance or<br />

clothing of someone. 10 Suitably then, forensics also plays a crucial role<br />

in Fashion Detective. Utilising methods inherent to textile conservation,<br />

including microscopy, x-radiography, scanning electron microscope<br />

(SEM) and ultraviolet (UV) scanning; chemical analysis in the form<br />

of x-ray fluorescence (XRF), Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy<br />

(FTIR), chromatography and specialist digital photographic processes,<br />

the exhibition considers the myriad ways that objects can be decoded.<br />

Unknown, Doll, 19th century<br />

X-ray of Doll, 19th century<br />

Cases such as ‘The secret in the doll’s dress ’ highlight what x-radiography<br />

and forensic photography can add to our understanding of an object.<br />

‘Reading’ the aged paper fragments secreted between layers of<br />

diamond-shaped silk patchwork in this dress produced unexpected<br />

information about its likely place and date of creation. Likewise, SEM<br />

analysis and microscopy enabled a positive medium ID in ‘The case of<br />

the fraudulent fur’, and also revealed new information about industry<br />

practice and social tastes.<br />

Fashion and colour<br />

Unknown, (China), Louis Vuitton, Paris (after), Speedy handbag, c.2014<br />

Handbags and wallets originating from China typically top the list, with<br />

Louis Vuitton products the most popular, particularly the Speedy and Alma<br />

monogram handbags. 7 As Dana Thomas writes:<br />

By putting an emphasis on the logo and spending millions to<br />

advertise it, luxury companies made their brands, rather than<br />

products, the objects of desire. They also created a demand that<br />

they couldn’t meet and a product average consumers couldn’t<br />

afford … Counterfeiters stepped in. 8<br />

Although highly problematic, contemporary fashion fakes are, for the<br />

majority, an acceptable consumer commodity. The House of Worth<br />

and Bobergh Bodice, however, is not – its circumstances are more<br />

Two investigations in Fashion Detective employ chemical analysis to<br />

explore the relationship between colour and fashionable aesthetics in<br />

the nineteenth century. Fashion today is based on a continuous cycle<br />

of new trends in which colour plays a key role: ‘grey is the new black’.<br />

Yet colour in fashion changed most radically in the nineteenth century<br />

following the accidental discovery of aniline purple (later named<br />

mauveine) in 1856 by a young Scottish chemist, William Henry Perkin<br />

(1838–1907), while he searched for a malaria cure. 11 Perkin’s finding<br />

was the catalyst for the emergence of a low-cost, artificial dyestuffs<br />

industry which produced colours that rapidly replaced traditional dyes<br />

made from plants and insects. Within a decade, textiles saturated with<br />

the new, gaudy chemical hues of synthetic colours, such as magenta,<br />

fuchsia, violet, aniline black, Bismark brown, methyl blue and<br />

malachite green, were in widespread use. 12<br />

4

Unknown, England, Dress, c.1865 (detail)<br />

Unknown, Australia, Dress, c.1865 (detail)<br />

By 1859 English newspapers such as Punch were satirising the extent to<br />

which Perkin’s vivid purple shade was dominating fashionable dress. (A<br />

novelty exacerbated by purple’s symbolic associations with aristocracy<br />

and royalty.) But what exactly did this colour look like? While a small<br />

swatch of silk dyed with a batch of the original dye is housed in the<br />

Imperial College chemistry archives, London, and an image of this<br />

can be seen on Wikipedia, records of Perkins purple are scant and<br />

identifying the colour by the naked eye is an impossible task. Employing<br />

chromatography and spectroscopy to analyse our holdings of mid to late<br />

nineteenth-century purple garments and accessories, this case attempted<br />

to locate evidence of this pivotal moment in fashion history.<br />

‘The case of the poisonous pigment ’ concerns the widespread use of<br />

green arsenical pigments as colouring agents in the early part of<br />

the nineteenth century. Discovered by Carl Scheele in 1778, and in<br />

widespread use by 1800, copper arsenate dyes such as Scheele’s Green,<br />

and later Schweinfurt green, were exceedingly popular due to their<br />

vivid hues. Cheap to make and chemically stable, the dyes were not<br />

only adopted by painters, cloth makers, wallpaper designers and dyers,<br />

but were also used to colour countless everyday goods, such as soap,<br />

candles, children’s toys, confectionary and packaging.<br />

By the late 1850s, after a three-year-old boy died after ingesting<br />

pigment flakes, anxiety about the prevalence of arsenic was expressed<br />

in British news articles, pamphlets and books. In 1862 a coroner’s<br />

inquest found that a woman died as a result of sucking an artificial<br />

grape coloured with Scheele’s Green. 13 At around the same time<br />

Australian newspapers reprinted reports from British medical journals<br />

warning of the dangers of arsenical green wallpapers (‘Put it up on<br />

your walls and you are lining your rooms in pure death’ 14 ) and listing<br />

the ghastly symptoms of arsenic poisoning, including ‘irritation,<br />

gastric derangement, ulceration, inflammation, palpitations, joint pain,<br />

irritability and weakness, and in the worst cases, memory loss, spasms<br />

and partial paralysis.’ 15<br />

Poisonings were also linked to the wearing of arsenical garments.<br />

London physician George Rees found green muslins to be especially<br />

hazardous after analysing a sample that contained sixty grains<br />

of Scheele’s green per square yard. The pigment was so loosely<br />

incorporated that ‘it could be dusted out with great facility’. 16<br />

Our fair charmers in green whirl through the giddy<br />

waltz … actually in a cloud of arsenical dust …<br />

Well may the fascinating wearer … be called a<br />

killing creature … she carries in her skirts poison<br />

enough to slay the whole of the admirers she may<br />

meet with in half a dozen ballrooms. 17<br />

John Leech, The Arsenic Waltz. The new Dance of Death. (Dedicated to the green wreath and dress-mongers.), 1862<br />

5

With this in mind, ‘The case of the poisonous pigment ’ asks if there is<br />

anything dyed arsenic green in the NGV collection, putting dresses,<br />

parasols, shoes, millinery and wallpapers through an XRF machine<br />

in order to ascertain traces of the deadly copper arsenate pigment.<br />

The results revealed something of the chemical composition of the<br />

nineteenth-century fashion palette.<br />

Material memories<br />

The garment is a ghost of all the multiple lives<br />

it may have had. Nothing is shiny and new;<br />

everything has a history. 18<br />

A less deadly form of evidence relates to factors of wear and use.<br />

As fashion scholar Amy de la Haye writes:<br />

Perhaps more than any other medium, worn clothing offers<br />

tangible evidence of lives lived, partly because its very materiality<br />

is altered by, and bears imprints of, its original owner. A<br />

garment’s shaping can become distorted in an echo of personal<br />

body contours. It can become imbued with personal scent, and<br />

bear marks of wear, from fabric erosion at the hem, cuffs and<br />

neck, to stains that are absorbed or linger on the surface of the<br />

cloth. 19<br />

Just as a study of the Bodice reveals that significant alterations were<br />

made for different wearers over two decades, other works in Fashion<br />

Detective disclose information about how they have been worn,<br />

used and cared for over their lifetimes. Within the exhibition, a<br />

wall of shoes interrogates the physical and scientific effects of time:<br />

threadbare surfaces, discolouration, corrosion, soiling, scuffing and<br />

creasing. These traces speak to the particularity of fashion collections<br />

and, by default, to the complex decisions that conservators and<br />

curators face in caring for these objects.<br />

Harrods, London, Travelling hatcase, 1901–04<br />

Unknown, Shoes, 1880–93<br />

Patterns of collecting also fall under scrutiny in Fashion Detective.<br />

Within the exhibition, ‘The case of the missing man’ examines<br />

fashion and the archive as means by which histories and memories<br />

are formed. Acknowledging that archives are by their very nature<br />

fragmentary, formed over time through a combination of institutional<br />

acquisition policies, curatorial impulse and voluntary donation, the<br />

case investigates why the NGV collection includes so little nineteenthcentury<br />

menswear. 20 Ostensibly a case about a lack of evidence, this<br />

enquiry considers what is salient about a group of four waistcoats,<br />

and asks: Are collections about what we see, or do not see?<br />

Unknown, England, Waistcoat, c.1845<br />

6

Within the exhibition, four ghostly white dresses recall this phenomenon.<br />

Each has a fragmentary piece of provenance information associated with<br />

it that forms one thread of a greater mystery: a torn wedding photograph,<br />

a newspaper clipping, a family story and a catalogue entry.<br />

Writing about fashion in fiction, Claire Hughes notes: ‘Descriptions<br />

of dress help us to fill out our pictures of the imagined words of fiction<br />

… They lend tangibility and visibility to character and context’. 26<br />

This potential of fashion to serve narrative ends is evident today in<br />

contemporary runway collections, where garments enact storylines,<br />

and in short films and photography where fashion is frequently<br />

cast as the central protagonist. The four short fictions in Fashion<br />

Detective draw on the complicity between clothing, fashion, crime and<br />

mystery in the nineteenth century. Scripting evocative and exciting<br />

new contexts for the works on display, these stories offer parallel<br />

encounters with the facts at hand. Here, fashion forms the very heart<br />

of fiction as the material evidence in a greater mystery.<br />

The game is afoot.<br />

Photograph of Wedding dress, 1939–74<br />

Fashion and fiction<br />

Although empirical modes of investigation underscore Fashion Detective,<br />

the exhibition is also deliberately speculative. It accepts we may never<br />

know the answers to our questions about the garments on display –<br />

who were they made by, who wore them, where are they from? – and<br />

so turns to fiction as a way of creating ‘cultural biographies’ for the<br />

works on display. 21 Exploiting the historical synergy between the<br />

establishment of professional detective agencies 22 and the rise of literary<br />

detectives in the nineteenth century, 23 Fashion Detective invited four of<br />

Australia’s leading crime writers – Garry Disher, Sulari Gentill, Kerry<br />

Greenwood and Lili Wilkinson – to create new short fictions based on<br />

objects from the NGV collection.<br />

Throughout the nineteenth century, clothing, along with other physical<br />

data, was pivotal to both crime solving and crime fiction, and a<br />

number of famous London cases rested on the discovery of clothing<br />

clues. In 1849 the infamous Bermondsey murderess Maria Manning<br />

who, along with her husband, killed her lover, was captured by way<br />

of a bloodstained dress she had stashed in a railway station locker. 24<br />

Similarly, the horrific Road Hill case of 1860, concerning the murder<br />

of three-year-old Saville Kent, centred on a missing nightdress.<br />

Fictional detective tales emulated forensic police work by incorporating<br />

material clues such as clothing and hair, objects that could be singled out<br />

and studied for information, into their storylines. In Charles Martel’s<br />

The Detective’s Notebook (1860), a button left at the crime scene holds the<br />

key to the case, and in Wilkie Collins’s The Diary of Anne Rodway (1856)<br />

a murderer is brought to justice via the discovery of the missing end of a<br />

torn cravat.<br />

The detective genre was so popular that it also started fashion trends.<br />

Collins’s sensation novel The Woman in White (1860), for instance, caused:<br />

Every possible commodity to be labelled ‘Woman in White’.<br />

There were Woman in White cloaks and bonnets, Woman in<br />

White perfumes and all manner of toilet requisites … music shops<br />

displayed Woman in White Waltzes and Quadrilles. 25<br />

Unknown, Bookmarks, c.1890<br />

Notes<br />

1 Valerie Steele, ‘A museum of fashion is more than a clothes-bag’, Fashion Theory: The Journal of Dress, Body and Culture,<br />

vol. 2, no. 4, 1998, p. 327. More recently, scholars have called for interdisciplinary approaches that recognise fashion’s<br />

engagement with contemporary visual and cultural discourses.<br />

2 Jules Prown, ‘Style as evidence’, The Winterthur Portfolio, vol. 15, 1980, p. 71.<br />

3 ibid.<br />

4 Miuccia Prada quoted in Dana Thomas, Duluxe: How Luxury Lost its Lustre, Allen Lane, London, 2007, p. 276.<br />

5 Samuel D. & Lewis A. Tallerman, ‘Notice: Pinet’s French boots’, Sydney Morning Herald, 25 Nov. 1878. I thank<br />

Bronwyn Cosgrove for drawing my attention to this article. Pinet also authorised Tallerman to take legal action<br />

against any persons found distributing counterfeit versions of his boots and shoes.<br />

6 Jack Ellis, ‘International – Counterfeiting statistics need to be backed up by consumer education’, 19 April 2013,<br />

World Trademark Review, , accessed 2 April 2014).<br />

7 Samuel Weigley, ‘The 10 most counterfeited products in America’, 24/7 Wall St, ,<br />

accessed 14 Jan. 2014.<br />

8 Thomas, p. 274.<br />

9 Nelson Goodman quoted in Michael Wreen, ‘Goodman on forgery’, The Philosophical Quarterly, vol. 33, no. 133, 1983,<br />

p. 340.<br />

10 Stephen Knight, Crime Fiction Since 1800: Death, Detection Diversity, 2nd edn, Palgrave Macmillan, New York, 2010,<br />

p. 56.<br />

11 Perkins was quick to realise the commercial application of his discovery. He filed a patent for the dye and within<br />

two years had established a small dye-making factory outside of London which synthesised aniline from coal tar – a<br />

readily available by-product of the coal gas and coke industries.<br />

12 Akiko Fukai, ‘The colours of a period as the embodiment of dream’, in Fashion in Colours: Viktor & Rolf & KCI, Kyoto<br />

Costume Institute, 2004, pp. 274–8.<br />

13 Paul Bartrip, ‘How green was my valance?: environmental arsenic poisoning and the Victorian domestic ideal’, The<br />

English Historical Review, vol. 109, no. 443, Sep. 1994, pp. 891–913.<br />

14 ‘Death on our walls’, Sydney Morning Herald, 26 July 1861, p. 8 (reprinted from London Review, 11 May 1861).<br />

15 ‘Arsenic in wallpapers’, Sydney Morning Herald, 5 Oct. 1871, p. 6 (reprinted from British Medical Journal).<br />

16 James C. Whorton, The Arsenic Century: How Victorian Britain Was Poisoned at Home, Work, and Play, Oxford University<br />

Press, Oxford, 2010, p. 181.<br />

17 ibid.<br />

18 Hussein Chalayan quoted in in Caroline Evans (ed.), Fashion at the Edge: Spectacle, Modernity and Deathliness, Yale<br />

University Press, New Haven, 2003, p. 57.<br />

19 Amy de la Haye, ‘Vogue and the V&A vitrine’, Fashion Theory; The Journal of Dress, Body and Culture, vol. 10, no. 1,<br />

2006, p. 129.<br />

20 The NGV collection has approximately 1200 Western garments and accessories from the period 1800–1900.<br />

Menswear and accessories account for 15 per cent of this collection.<br />

21 See Igor Kopytoff, ‘The cultural biography of things: commoditization as process’, in Arjun Appadurai (ed.), The Social<br />

Life of Things: Commodities in Cultural Perspective, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1988, pp. 64–91.<br />

22 The French Sûreté was established in 1811, and Scotland Yard sent out its first plain-clothes detectives in 1842.<br />

23 Edgar Allan Poe’s The Murders in the Rue Morge (1841) is generally accepted as the first iteration of this new literary<br />

genre.<br />

24 Kate Summerscale, The Suspicions of Mr Whicher; or, The murder at Road Hill House, Bloomsbury, London, 2008,<br />

p. 69.<br />

25 Stewart Marsh Ellis, Wilkie Collins, Le Fanu and Others, Constable, London, 1931. The Woman in White was reprinted six<br />

times in its first six months of publication.<br />

26 Clair Hughes, Dressed in Fiction, Berg, New York, 2006, p. 1.<br />

7

Unknown, England, Carriage dress, c.1830<br />

9

Unknown, Australia, Dress, c.1865<br />

10

Unknown, Australia, Dress, c.1878<br />

11

Unknown, Australia, Wedding dress, c.1885<br />

12

Mme Delbarre, London (dressmaker), Mourning gown, 1885–90<br />

13

14<br />

The case<br />

of the fake<br />

Worth

Examination report<br />

Annette Soumilas<br />

Case<br />

The case of the fake Worth<br />

Item<br />

Bodice, c.1885<br />

Summary<br />

Bodice, presented to the National Gallery of Victoria by Miss<br />

M. Bostock in 1963, and labelled the House of Worth and Bobergh,<br />

poses a number of curatorial questions relating to authenticity: is<br />

the label for this bodice authentic? Does the styling of the bodice<br />

correspond with the date of the label? Was the label attached to<br />

the bodice at the time of its manufacture, or at a later date? Did<br />

the bodice have multiple owners? Historical and technical analysis<br />

of the garment and its label by the NGV’s Textile Conservation<br />

department suggests that the label may indeed be authentic, and<br />

possibly rare, and that the bodice may have passed through the<br />

hands of several owners. The problem, then, is determining the<br />

authenticity of this label and, by default, of the bodice itself.<br />

Background information<br />

English-born dressmaker Charles Frederick Worth (1825–95) was<br />

one of the most celebrated designers of the nineteenth century,<br />

known as the ‘father of haute couture’. His clients included royalty,<br />

the famous and the wealthy. Many examples of his work exist in<br />

museum collections today, mostly identifiable by couture labels. Our<br />

knowledge of his work is communicated by these primary sources.<br />

A nineteenth-century couture house’s public image, the protection<br />

of its designs, and all its industrial power were conveyed through<br />

its label. 1 The practice of attaching fake and counterfeit labels to<br />

garments existed at this time, as it still does today, to ‘authenticate’<br />

garments of dubious origin, and thereby to increase their value. By<br />

signing his creations Worth placed himself on an equal footing with<br />

artists who sign and personify their work. From this gesture, the<br />

‘magic of labelling grew by creating an aura that then spread to the<br />

label’s products’. 2<br />

The system of labelling was used for mass-produced fashionable<br />

accessories, such as shoes and hats, from as early as 1780. 3 Worth<br />

continued this established tradition and, when he opened his own<br />

couture house in 1858 in partnership with the Swede Otto Gustaf<br />

(Gustave) Bobergh (1821–1881), he was the first to extend the<br />

practice of labelling to identify his garments.<br />

The distribution of clothes was a well-established practice in the<br />

nineteenth century. Labelled garments were not necessarily owned<br />

by one individual only. A hierarchy for cast-off garments existed to<br />

facilitate the disposal of clothes, which were frequently altered to<br />

fit a new owner. Worth and Bobergh boasted a wealthy clientele.<br />

Many serving women to royalty and the upper-classes received castoff<br />

garments from their employers. As these items of clothing could<br />

be sold to secondhand traders, they were a great source of profit to<br />

domestic staff. Many of these garments would eventually end up<br />

in the hands of rag-pickers or in the wardrobes of theatres. Along<br />

the way, labels identifying the garment would be transferred to<br />

‘authenticate’ the garment, thus enhancing its saleability. 4 This practice<br />

could easily have extended to the Worth client and her servants.<br />

Beyond construction details, fabric is also an important consideration<br />

in this investigation. Worth always retained a preference for figured<br />

textiles, which were quite popular during the 1850s but fell out<br />

of favour during the 1860s. In 1872 Worth attempted to relaunch<br />

‘figured, cut velvet’, but his clients did not share his enthusiasm,<br />

maintaining that ‘they did not (want) to be dressed like furniture’.<br />

Worth’s taste was vindicated in the 1880s and 1890s when the fashion<br />

for these textiles prevailed. 5<br />

The genre of fabric which enjoyed the greatest degree of favour<br />

during the 1880s was unquestionably velvet and plush. In the October<br />

1881 issue of L’Art de la Mode, Jenny Lensia wrote:<br />

Velvet is the shimmering setting that best sets off the<br />

beauty of the woman; simple in its magnificent elegance,<br />

it marvellously highlights the sculptural forms of those<br />

who are truly beautiful … All women dressed in velvet<br />

appear majestic.<br />

Luis Jimenez y Aranda, Le Carreau du Temple, Paris, 1890, private collection<br />

Unknown (France), Bodice, c.1885 (detail)<br />

15

Evidence<br />

According to Worth’s biographer Diana De Marly, the first original<br />

Worth label appeared in 1860, after Worth became couturier to<br />

the Empress Eugenie (1826–1920). 6 The label was stamped in gold<br />

capital letters: ‘WORTH AND BOBERGH, 7 RUE DE LA PAIX,<br />

PARIS’, and included Eugenie’s coat of arms. Bodice’s label is stamped<br />

in gold on white Petersham ribbon with the words ‘WORTH AND<br />

BOBERGH, 7 RUE DE LA PAIX AU PREMIERE’.<br />

Unknown (France), Bodice, c.1885 (label detail)<br />

Unknown (France), Bodice, c.1885 (detail)<br />

Worth & Bobergh, Paris, Bodice, 1860s, collection of Martin Kramer<br />

The font and use of gold on white Petersham is thus consistent with<br />

an authentic Worth label. The words ‘Worth and Bobergh’ and<br />

the inclusion of the address, specifically au premiere (the first floor),<br />

suggests that this label was used by Worth during the two years<br />

(1858–60) when he first opened his house in rue de la Paix, before the<br />

Empress Eugenie became his client.<br />

The garment itself is made from black figured cut silk velvet<br />

featuring a rose and fern – motif which during the nineteenth century<br />

represented sorrow and mourning. The bodice lining is constructed<br />

from silk, whilst the sleeves are lined with cotton. The jacket is<br />

fastened at its centre-front by dark blue velvet-covered buttons, and<br />

features internal boning of baleen and metal. The rose and fern motif,<br />

coupled with the black colour of the cloth also suggests that the bodice<br />

could have been worn during the late 1850s and 1860s for mourning.<br />

X-ray of Bodice, c.1885 (detail)<br />

16

Unknown (France), Bodice, c.1885 (interior detail)<br />

Unknown, Australia, Dress, c.1865 (detail of bodice pattern showing no back seam)<br />

Unknown, Australia, Dress, c.1885, (detail of bodice pattern showing centre back seam and peplum)<br />

Unknown, France, Bodice, c.1885 (detail of bodice pattern showing no back seam and peplum addition)<br />

Bodice shows evidence of extensive alterations that resulted from<br />

restyling and refitting, probably executed at intervals between<br />

c.1860 and c.1885. Unfortunately, only traces of hallmark couture<br />

dressmaking techniques are evident due to these extensive alterations.<br />

Conclusion<br />

If the label is authentic, it would have been in use during the initial<br />

two years of Worth and Bobergh’s partnership. During these years,<br />

the Worth establishment was, according to De Marly, ‘far from being a<br />

stately salon’. 7 However, Worth’s clever self-promotion soon attracted<br />

a wealthy and fashionable clientele. Although the bodice has been<br />

extensively altered, traces of styling from c.1860 are evident, as are<br />

alterations that correspond to styling of the mid 1880s. The fabric from<br />

which the bodice is constructed is of very high quality and its colour<br />

was fashionable in the later decades of the century. The rose and fern<br />

motif suggests that the bodice could have been worn for mourning<br />

in the 1860s, and later as a fashionable choice during the 1880s. It is<br />

likely that the garment changed hands several times. The label alone,<br />

and the cloth from which it is constructed, has enough value to have<br />

sustained alterations and wear over twenty-five years.<br />

Whether the label was attached to the bodice at the time of its<br />

manufacture remains indeterminable.<br />

The NGV’s Textile Conservation department would like to thank textile and costume<br />

collector Martin Kamer for his generous advice.<br />

NOTES<br />

1 Olivier Saillard & Anne Zazzo (eds), Paris Haute Couture, Flammarion, Paris, 2013, p. 26.<br />

2 ibid., p. 29.<br />

3 ibid., p. 26.<br />

4 E. A. Coleman, The Opulent Era: Fashions of Worth, Doucet and Pingat, Brooklyn Museum<br />

in association with Thames and Hudson, London, 1989, pp. 32–3.<br />

5 Saillard & Zazzo, p. 31.<br />

6 Diana De Marly, Worth: Father of Haute Couture, Elm Tree Books, London, 1980, p. 39.<br />

7 ibid., p. 34.<br />

17

THE<br />

REAL McCOY<br />

He followed her to a poky parlour furnished with sagging<br />

armchairs, a scarred table and dressmaking paraphernalia.<br />

On a bust, half completed, was a long-sleeved, tight-waisted<br />

woman’s jacket. Byrne went straight to it, the young woman<br />

watching bewilderedly.<br />

Garry Disher<br />

18

Garry Disher<br />

arvellous Smelbourne, thought Detective Byrne, kicking<br />

at a rat and stepping over the alleyway’s sewerage drain.<br />

The rat looked better fed than the Collingwood urchins<br />

who tugged at Byrne’s coat-tails.<br />

‘Who are you, Mister?’<br />

A thin hand crept into his pocket. Byrne swiped it away<br />

and knocked on the warped door to No. 23. A young woman<br />

answered, whispering, ‘Yes, sir?’<br />

Black hair in a French knot, a tense hand clutching her<br />

collar, and quite beautiful, Byrne realised. He removed his hat.<br />

‘Detective Byrne, Mrs McCoy.’<br />

‘Is it about Albert?’<br />

‘May I come in?’<br />

He followed her to a poky parlour furnished with sagging<br />

armchairs, a scarred table and dressmaking paraphernalia. On a<br />

bust, half completed, was a long-sleeved, tight-waisted woman’s<br />

jacket. Byrne went straight to it, the young woman watching<br />

bewilderedly.<br />

‘A poor copy, Mrs McCoy.’<br />

Her puzzlement increased. ‘Beg pardon, sir?’<br />

He opened a wing of cloth to reveal the Worth label. ‘By<br />

representing these as real, you are breaking the law.’<br />

All at sea, she collapsed into a chair. ‘But Albert said we<br />

was licensed.’<br />

‘He lied’, said Byrne gently, eyeing photographs on a<br />

mantelpiece: McCoy the gentleman, a hand on the shoulder of<br />

his seated wife; McCoy the sea captain; McCoy standing guard<br />

over captured Kanakas on board a blackbirding ship.<br />

‘I swear to you, sir, I had no idea …’<br />

She rallied, tilting her lovely face to him. ‘I sewed day and<br />

night so we might have food!’<br />

Byrne nodded. All through the colony factories were closing,<br />

leaving the poorhouses and charities overstretched. He knelt beside her.<br />

‘Tell me where he is, Mrs McCoy, and I’ll see what I can do.’<br />

She clutched him. ‘He has been gone this past week, and not<br />

a word.’<br />

In the wind, thought Byrne, leaving this beautiful creature<br />

behind. He felt an unaccountable desire to embrace her, and<br />

sensed that she might welcome it, in her loneliness and misery.<br />

But he had work to do. ‘If Albert returns, Mrs McCoy, urge<br />

him to turn himself in.’<br />

Unknown, France, Bodice, c.1885<br />

Byrne left the noxious laneways and returned to police headquarters,<br />

passing drunks, ratcatchers and constables evicting tenants behind on<br />

their rent. The Force had been shaken up in the years since the Kelly<br />

Outbreak, but still policemen were expected to do the work of the<br />

moneyed classes. If I were Police Commissioner, Byrne thought …<br />

He reported to his inspector, attended to paperwork and, as<br />

evening fell, headed to Carlton and his lonely room in an Elgin<br />

Street boarding house. But first he called reluctantly at a grand<br />

house in Macarthur Square, where he informed Mr Edmund<br />

Longmire, of the Longmire Emporium, that he’d made progress<br />

in his search for the man who, pretending to be a representative<br />

of a famous French haute couture company, had gone about the<br />

city selling fake Worth jackets.<br />

Longmire, a man composed of expensive cloth, whiskers and<br />

apoplectic cheeks, demanded to know what kind of progress.<br />

‘We know who he is, sir, and will soon have him behind bars.’<br />

Longmire looked down his veiny nose at Byrne. ‘What good is<br />

that to me? I am a laughing stock and out of a hundred pounds.’<br />

Lifting his hat to the man, Byrne left, swearing never to let<br />

Longmire know where Mrs McCoy lived. The thought of those<br />

meaty hands around her fine neck … No, a bully like Longmire<br />

would hire ruffians, he thought.<br />

19

Unknown, Australia, Waistcoat, 1890<br />

bluestone wall, a shotgun resting on his torso. His right thumb<br />

was hooked on the trigger and his face was a mess of bone and torn<br />

flesh. He wore black trousers and jacket over a bright waistcoat with<br />

yellow piping.<br />

Stewart & Co., Melbourne, Australia, 1879–96, No title (Young bearded man), carte-de-visite, 1880s<br />

Three days later the body was found by a child as she walked from<br />

her tenement home, near Queen Victoria Market, to the Pym Shoe<br />

Company in Fitzroy. Running down an alley behind Macarthur<br />

Square in the pre-dawn light, she’d tripped over a pair of legs.<br />

‘I were late for work, sir’, she told Byrne.<br />

She hawked and spat into a grimy rag, which she returned to<br />

her sleeve. Wheezing, trembling, she said, ‘Beg pardon, sir’.<br />

Byrne patted her arm. The girl probably stitched shoe leather<br />

twelve hours a day in poisonous, unventilated air.<br />

‘Just lying there with no face’, she continued, glancing back<br />

shakily, even though Byrne had moved her away from the body,<br />

out onto the Square.<br />

‘You saw no one?’<br />

She shuddered. ‘Only me and him, sir.’<br />

Byrne penned a note to her employer, arranged a cab for the girl<br />

and returned to the body. Albert McCoy sprawled where the shadows<br />

were deepest, his legs splayed on the cobblestones, his spine against a<br />

Beside the body was a sample case spilling Worth jackets and an<br />

album of cartes-de-visite depicting McCoy wearing the same waistcoat.<br />

Each had been printed by Stewart and Co. of Bourke Street, with the<br />

name M. Henri DeSalle written on the back.<br />

Byrne snorted. ‘Albert, Albert …’<br />

Spotting a tuft of white in McCoy’s waistcoat pocket, Byrne<br />

pulled out a sheet of folded paper.<br />

‘To my darling wife’, he read:<br />

‘Pray Forgive me, dear Connie, but I am Burdened by Guilt and Regret<br />

for Deceiving you, Mr Longmire and many others. I have brought Shame to<br />

you and must now put it Right. You are yet Young and will find your way.<br />

I have led a full life. Your loving Husband, Albert.’<br />

Connie, Constance, thought Byrne. He glanced over the wall.<br />

For Albert McCoy to shoot himself dead against Longmire’s back<br />

wall was a gesture either of atonement or contempt. He sighed. He<br />

was obliged to tell Longmire, but would take pleasure in reporting<br />

that no, a hundred pounds had not been found on the corpse.<br />

The next day, still tingling from the sensation of Connie McCoy’s<br />

slender, grieving form clutching him in the viewing room of the<br />

morgue that morning, Byrne attended the autopsy.<br />

‘One Albert Aloysius McCoy’, he told the police surgeon.<br />

The surgeon looked doubtfully at the torn face. ‘If you say so.’<br />

20

A. J. White, London (hatter), Top hat, 1901–04 (detail)<br />

A. J. White, London (hatter), England, Top hat, 1901–04<br />

‘His personal effects attest to that,’ said Byrne, ‘and his widow<br />

identified his remains this morning’.<br />

‘A wife knows her husband’, the surgeon said.<br />

He sniffed the naked torso. ‘Carbolic. This fellow’s been in a<br />

hospital.’<br />

The missing days, thought Byrne. And McCoy did look ill, a<br />

shadow of the man portrayed in his studio photographs. Gaunt,<br />

pale, scarred, with battered hands, the left noticeably larger than<br />

the right.<br />

As if reading Byrne’s mind, the surgeon pointed with a scalpel.<br />

‘Left-handed.’<br />

And so the autopsy proceeded. Bored, queasy, Byrne elected<br />

to sift through McCoy’s belongings. A poor collection for the<br />

widow: the cartes-de-visite, a handkerchief, a sixpence and a small<br />

bottle of Mrs S. A. Allen’s World’s Hair Restorer.<br />

He snorted, examining a carte-de-visite for further evidence of<br />

McCoy’s vanity. A full head of hair, a stout chest, a fine suit and a<br />

cocky pose, right fist deep in a waistcoat pocket.<br />

Just then, Byrne’s skin crept. He swallowed. He peered at<br />

the waistcoat. The right pocket, habitually used by McCoy, was<br />

stretched and shapeless. He checked the hair restorer. It claimed to<br />

‘restore Gray, White, or Faded Hair to its youthful Colour, Gloss<br />

and Beauty’.<br />

Re-joining the surgeon, he asked, ‘This fellow is left-handed?’<br />

‘Indeed.’<br />

‘In poor health?’<br />

‘Inadequate nourishment, hard manual labour, alcohol … I<br />

see it often in destitute men who, at death’s door, are removed to a<br />

rest house by hospitals anxious to avoid the expense of a funeral.’<br />

‘Almost bald.’<br />

‘Lost his hair long ago.’<br />

‘Was he dead before he was shot?’<br />

It was the surgeon’s turn to freeze, shears poised to crunch<br />

open McCoy’s ribcage. ‘An interesting question.’<br />

Byrne hurried back to the Detective Branch where he used the<br />

telephone exchange to call the Port of Melbourne. A coastal tramp had<br />

steamed out of Port Phillip that morning, bound for Sydney; a clipper<br />

would sail for London that afternoon; and various smaller craft would<br />

be coming and going.<br />

Byrne raced out and hailed a cab. Feeling tense, powerless and<br />

bounced about by the carriage, he calmed himself by working out<br />

the stages of the deception. McCoy learns the police are closing<br />

in. A man given to deception, he fakes his own death using one of<br />

the city’s forgotten men. And with no face to aid identification, a<br />

harried policeman might rely on a handful of belongings.<br />

Another outrage for poor Constance.<br />

‘We’re here, Guv’nor’, the cabbie said.<br />

Gulls wheeled and screeched, smokestacks eddied, stevedores<br />

shouted, whistles blew. Spotting the London-bound clipper,<br />

passengers milling at the gangway, Byrne ran, casting about for a<br />

tall, vigorous man who no doubt had changed his appearance.<br />

But what stopped the detective was not McCoy. What stopped<br />

him was a lovely tilted chin glimpsed through the throng, a slender<br />

neck, a pretty cheek tucked against a solid arm. Here was the<br />

final stage of the deception. Gathering himself, Byrne straightened<br />

his tie, buttoned his jacket, removed his pistol and cuffs. ‘Albert<br />

McCoy, I presume?’ he said, confronting the husband, trying not<br />

to show his hurt to the wife.<br />

21

23<br />

The case of<br />

the poisonous<br />

pigment

Examination report<br />

Bronwyn Cosgrove<br />

Case<br />

The case of the poisonous pigment<br />

Item<br />

Daisy and Trellis wallpapers, designed 1864<br />

Summary<br />

In 2003 analysis of a sample of Morris & Co.’s Trellis, wallpaper<br />

by Andy Meharg of the School of Biological Sciences, University<br />

of Aberdeen, Scotland, identified the presence of copper arsenic salt<br />

in the green paint. 1 Morris & Co. wallpapers in the NGV collection<br />

were similarly suspected of containing arsenic compounds. This<br />

investigation set out to prove or disprove the theory.<br />

Background information<br />

Illness or death relating to the abundance of arsenic-based pigments<br />

is a key popular narrative of the nineteenth century. Arsenic-based<br />

green pigments were widely used to dye fabrics and foodstuffs, such<br />

as sweets and desserts, and were also used extensively in paints and<br />

wallpapers. In 1858 an article in The Times estimated that British<br />

homes contained 100 million square miles of arsenic-rich wallpaper,<br />

and that a 100 m2 room might contain 2.5 kg of arsenic. 2<br />

Identification of arsenic-based pigments in William Morris wallpaper<br />

has been a point of discussion as it juxtaposes Morris’s background<br />

as a shareholder in Devon Great Consuls (DGC), a mine that became<br />

the world’s largest source of arsenic, against his utopian socialist ideals.<br />

There is evidence to suggest that Morris was not overly alarmed<br />

about the health risks associated with arsenic in wallpapers. Concerns<br />

advocated by articles in The Lancet during the 1860s and the general<br />

press through the 1870s, most notably an 1875 campaign in The Times<br />

that described DGC as containing enough arsenic to poison the entire<br />

world, seem to have had little impact on the designer. 3 In correspondence<br />

to his dye manufacturer Thomas Wardle in October 1885,<br />

Morris wrote:<br />

As to the arsenic scare, a greater folly is hardly possible to<br />

imagine: the doctors were being bitten by witch fever … It is<br />

too much to prove that the Nicholson family were poisoned by<br />

wallpapers: for if they were a great number of people would<br />

be in the same plight, and we would be sure to hear of it. 4<br />

Morris & Co., London (distributor), William Morris (designer), Jeffrey & Co., London (printer),<br />

Daisy, wallpaper, 1864<br />

Morris & Co., London (distributor), william morris (designer), Phillip Webb (designer), jeffrey &<br />

co., London (printer), Trellis, wallpaper, 1864 (designed)<br />

24

x 1E3 Pulses<br />

5<br />

Calcium<br />

19th century emerald green watercolour pigment<br />

Zinc<br />

Morris & Co Daisy – green leaf<br />

Morris & Co Trellis – green foliage<br />

4<br />

Barium<br />

Barium<br />

Arsenic<br />

Lead<br />

2<br />

Chronium<br />

Copper<br />

Lead<br />

Iron<br />

Zinc<br />

Arsenic<br />

Lead<br />

0<br />

2 4 6 8 10 12 14 16<br />

– keV–<br />

XRF spectra of emerald green pigment (copper arsenite) control against green samples from wallpapers<br />

Process<br />

After visual examination, NGV conservators employed x-ray fluorescence<br />

(XRF), a non-destructive form of analysis that is useful in the<br />

identification of metals, mineral and pigments, to identify the presence of<br />

arsenic in each object. XRF utilises a beam of radiation to force changes<br />

in the sample at an atomic level. These changes result in the release of<br />

secondary x-rays, the energies of which are characteristic of individual<br />

elements, and can be used to identify elements present in a sample.<br />

Evidence<br />

In contradiction to the analysis carried out by Professor Meharg, XRF<br />

analysis of the NGV Daisy and Trellis wallpapers did not indicate the<br />

presence of arsenic-based green pigments. Trellis is Morris’s earliest<br />

wallpaper pattern and one of his most popular. Registered in 1864,<br />

printing for both wallpapers was contracted to Jeffrey & Co., London.<br />

Printed with wood blocks and distemper – a mixture of pigment,<br />

animal glue and whiting (calcium carbonate) – the wallpapers’<br />

patterned areas are thick and have a chalky surface. Jeffrey & Co.<br />

continued to print for Morris & Co. until 1927, when work was taken<br />

over by Arthur Sanderson & Sons. 5<br />

The absence of arsenic in the NGV samples could be attributable<br />

to a difference in the pigments used in different colour ways, or it<br />

could be explained by the fact that Morris & Co. discontinued the<br />

use of arsenic-based green pigments in 1883, replacing them with less<br />

toxic green pigments 7 . The presence of chromium in the spectra may<br />

indicate the use of the green pigment chrome oxide. That arsenic is<br />

not present in XRF spectra for the NGV samples could indicate that<br />

both wallpapers were produced after this date.<br />

Conclusion<br />

As arsenic is not present, these wallpapers would not have evolved<br />

volatile poisons in damp circumstances, however it is interesting to<br />

note the presence of lead, possibly in the form of lead oxide: a white<br />

pigment that may have been employed to create a pale shade of green.<br />

Due to its wide use in paints, lead has taken on the mantle of the<br />

domestic interior poison of the twentieth century.<br />

NGV Conservator undertaking XRF analysis<br />

I would like to express my thanks to Deb Lau, CSIRO, and Michael Varcoe-Cocks,<br />

Head of Conservation, NGV, for their assistance with this project.<br />

Notes<br />

1 Andy Meharg, ‘The arsenic green’, Nature, vol. 432, no. 688.<br />

2 Paul Bartrip, ‘How green was my valance?: environmental arsenic poisoning and the Victorian domestic ideal’, The<br />

English Historical Review, vol.109,issue 433, September 1994, p.904<br />

3 Patrick O’Sullivan, ‘William Morris and arsenic – guilty, or not proven? ’, William Morris Society Newsletter, 2012, p. 12.<br />

4 Norman Kelvin, The Collected Letters of William Morris, vol. 2, Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ, pp. 463-4.<br />

5 LesleyHoskins, ‘Wallpaper’, in Linda Parry, William Morris, Philip Wilson Publishers in association with The Victoria<br />

and Albert Museum, London, pp. 198–223.<br />

6 O’Sullivan, p. 12.<br />

25

THE<br />

BEQUEST<br />

If your lodgings are not to your liking, sir, then depart.<br />

But allow me to remind you that the terms of Millicent’s<br />

bequest were unambiguous.<br />

Sulari Gentill

Sulari Gentill<br />

eginald Kane was untroubled as he stepped through<br />

the doorway of the very room in which she’d taken her<br />

life. It was, after all, just a room. He did not quail at the<br />

indelible bloodstains on the wall, but rather studied the<br />

grim splatter with an unseemly scientific curiosity.<br />

‘I shall take the rooms down the hallway.’ Edward Mayfield’s<br />

voice was cold, chilled with an unveiled contempt for the callous<br />

blackguard to whom he was about to hand the keys<br />

to his sister’s house.<br />

‘Very well.’ Kane rocked back on his heels, thumbs hooked<br />

in the pockets of his waistcoat. He considered the room itself. It<br />

was easily the best in the house, generously proportioned with a<br />

rather pleasant outlook over the rose gardens. The plasterwork<br />

on the ceiling was in excellent condition despite evidence of rising<br />

damp, and the walls … well, they could be papered. He shook<br />

his head. Poor Millicent – fragile, desperate girl. How carefully<br />

she had planned her melodramatic revenge, convinced that this<br />

room would conjure some torment on her behalf. He might<br />

have laughed if not for Edward Mayfield. ‘You’ll organise for the<br />

room to be decorated, I presume?’ he asked, tapping the soiled<br />

paintwork with the silver pistol-grip of his walking stick.<br />

‘Yes.’ Edward could barely look at the man. The vain peacock<br />

who called himself learned. Millie’s murderer. Millie’s heir.<br />

‘I shall send you some swatches.’ Kane inspected the French<br />

lace curtains disdainfully. ‘I’m afraid Millicent will not be<br />

remembered for her good taste.’<br />

Edward’s jaw tensed, his dark eyes flashing dangerously as<br />

he looked Kane up and down. Millie’s bloody blue-eyed prince.<br />

‘Quite’, he said, but nothing more. His sister’s wishes had been<br />

clear and Edward was determined to fulfil this last duty. Under<br />

his wardenship Reginald Kane would serve the sentence Millicent<br />

had, in her despair, died to impose.<br />

Kane smiled. He knew well that Edward Mayfield loathed<br />

him, blamed him for a madwoman’s decision to destroy herself.<br />

Kane shook his head: the grieving fool was conspiring with his<br />

dead sister to punish the man who’d disappointed her. The whole<br />

family was insane.<br />

‘I say, Mayfield old chap, can’t we simply come to an<br />

understanding?’ he suggested. ‘Surely you have places you’d<br />

rather be? Surely there are debutantes in Melbourne who’d be<br />

more welcoming of your attentions than I?’<br />

Edward flared, grief and fury suddenly unguarded on his<br />

face. ‘Do not think I will tire of my charge, Kane. Sleep a single<br />

night outside that room and I will be here to know, to deny you<br />

one more penny of Millicent’s fortune!’<br />

Kane rolled his eyes. He was a man of science who no more<br />

believed in spirits than in fairies. He’d happily sleep a year in<br />

this room to inherit the estate and, he expected, he would sleep<br />

quite well.<br />

The wallpaper was imported, a William Morris design in Scheele’s<br />

green. It buried all signs of damp, and Millicent, beneath a pattern of<br />

clumped daisies. The effect was cheerful without being too feminine.<br />

Morris & Co., London (distributor), William Morris (designer), Jeffrey & Co., London (printer),<br />

Daisy, wallpaper, 1864<br />

The colour had not been Kane’s first preference, but he liked it rather<br />

well. Edward Mayfield, it seemed, had the kind of refined taste that<br />

had eluded his dreary sister.<br />

The once-struggling schoolteacher surveyed the bedchamber<br />

as he loosened his cravat. The fire was lit, the warm, merry<br />

movement of the flames casting the room in gentle light. The<br />

furniture was new and of a quality befitting his recent social<br />

elevation. With a deep sigh of contentment, Kane inspected the<br />

tall cedar chest of drawers, charmingly lined with wallpaper<br />

remnants. Every detail of his windfall was exquisite. A servant<br />

had laid out his nightclothes on the bed and placed a balloon of<br />

brandy on the side table by his armchair. Smiling, Kane hung<br />

his jacket on the mahogany dumb valet. If he’d known Millicent<br />

possessed such a fortune he might have agreed to marry her and<br />

given that pompous headmaster his notice months ago.<br />

No matter. It had all worked out rather well anyway.<br />

It was a month before Reginald Kane came to be less self-satisfied<br />

with his good fortune, and another before he began to suspect he was<br />

being poisoned. Initially he’d dismissed the abdominal cramps and<br />

breathlessness as passing maladies that a man was bound to contract<br />

from time to time. Perhaps he’d been indulging too heartily in the rich<br />

food and plentiful whisky to which his new address gave him access?<br />

So, he asked for simple suppers and drank only with his meals.<br />

With no improvement, however, he wondered if Edward<br />

Mayfield’s dour presence was having an effect on his digestion.<br />

Surely the man’s vindictive demeanour was sufficient to curdle<br />

the contents of any gut? And so the erstwhile schoolteacher took<br />

27

to dining alone in his room. Still the pains continued and seemed,<br />

indeed, to become more severe.<br />

It was then that Kane became frightened. Was Mayfield<br />

poisoning him, lacing his meals with some evil toxin? He<br />

considered now whether he’d been too blithe in taking up<br />

residence with mad Millicent’s brother. Was the scoundrel plotting<br />

to avenge his sister with murder?<br />

Kane fed his next meal to Mayfield’s beagle, but the<br />

hound showed no ill effects at all. Neither did the cat, nor the<br />

cook’s young son to whom he gave the pudding. Despite this,<br />

Kane began to dine at his gentlemen’s club, carefully avoiding<br />

any consumption that Edward Mayfield may have had the<br />

opportunity to contaminate. And for a time his constitution<br />

seemed restored, but the rally was short-lived and his health<br />

proceeded, once again, to decline.<br />

Edward Mayfield observed his breakfast companion from behind<br />

The Argus. Kane was, as always, immaculately groomed, but his eyes<br />

were sunken and shadowed in a face that was sickly pale. He touched<br />

neither food nor drink, nervously arranging and rearranging his cutlery<br />

instead. ‘How did you sleep, Mr Kane?’ Edward asked with practised<br />

civility.<br />

Kane regarded him sharply, suspiciously. ‘Is it your intention<br />

to exhaust my reason, Mayfield? Is that what you are doing, sir?’<br />

Edward’s brow rose. ‘I’m sure I don’t know what you mean,<br />

Mr Kane. I do not recall making any demands on your ability to<br />

reason. Indeed, I have kept our conversations as simple as I can<br />

manage in deference to your abilities.’<br />

‘You know exactly what I mean!’ Kane spat. ‘What tricks<br />

have you employed to keep me from sleep? This unrelenting<br />

illness that will not leave me be ...’ He stopped to cough, wincing<br />

when the paroxysms finally abated. ‘Let me tell you now,<br />

Mayfield,’ he spluttered, ‘you will not oust me with schoolboy<br />

pranks!’<br />

Edward went back to his paper. ‘What exactly is your<br />

complaint, Mr Kane?’<br />

‘I am disturbed at night …’ Kane faltered.<br />

‘Perhaps that’s your conscience.’<br />

‘My conscience is untroubled, Mayfield! Your sister’s death<br />

was nothing to do with me.’<br />

‘Is that so?’ Edward slammed down his newspaper. ‘You<br />

wooed her, lied to her, seduced her with your intellectual<br />

gibberish and then, when she could see no future but you, you<br />

ruined and discarded her so callously that she turned a shotgun<br />

upon herself in a manner that denied her and her family even the<br />

solace of a Christian burial!’<br />

Kane coughed again. Edward waited until he’d stopped. ‘If<br />

your lodgings are not to your liking, sir, then depart. But allow<br />

me to remind you that the terms of Millicent’s bequest were<br />

unambiguous. You’ll inherit nothing unless you sleep a year in the<br />

room in which she died!’<br />

Kane blanched. His debts had accrued at an alarming rate<br />

over the past months – meals at the club, not to mention dues,<br />

carriages, acquisitions of fine new clothes to suit his station,<br />

champagne. Without Millicent’s legacy he would be bankrupted.<br />

So he said nothing.<br />

‘If you are ill I will send for a doctor’, Edward Mayfield<br />

offered darkly.<br />

‘I, sir, will retain my own’, Kane wheezed.<br />

‘As you wish, Mr Kane’, Edward replied. ‘Though a priest<br />

might be of more use.’<br />

‘A priest? Do you threaten me, Mayfield?’<br />

‘I simply suggest that your haunted conscience may be more<br />

appropriately treated by a man of the cloth.’<br />

Dr Arthur Carrington was a fellow member of Reginald Kane’s club.<br />

They were friends of a sort. Carrington’s manner befitted the easy<br />

expansiveness of his stature, and his company was of great comfort to<br />

his troubled patient. He laughed at the notion that Kane’s illness was<br />

caused by some spiritual cause. ‘My dear fellow, I do not believe in<br />

curses. You will find that simple treatable disease is the cause of your<br />

current troubles.’<br />

The physician then set about to address Kane’s symptoms with<br />

medical science. He diagnosed diphtheria and instructed that the<br />

windows be closed and the fire stoked. Under his orders a vaporiser<br />

was installed and the stricken schoolteacher confined to bed.<br />

Reginald Kane lay back on the soft pillows, relieved,<br />

comforted by the certainty of modern medicine. The kerosene<br />

flame of the vaporiser burned, releasing steam continuously from<br />

its place in the corner, and the air soon became warm and moist.<br />

The now familiar hacking cough seized him again. Carrington<br />

had given him a draught to help him sleep. For some reason<br />

unknown, Kane thought of Millicent as he drifted finally into the<br />

arms of Morpheus.<br />

When the door was forced, Edward Mayfield allowed the constables<br />

to enter first. The room was uncomfortably close, and what air<br />

remained in it was damp. The walls dripped. It was probably this<br />

which had swelled the timbers of the doorjamb and sealed the<br />

bedchamber like a crypt.<br />

Edward held a handkerchief to his face against the odour – a<br />

peculiar, mousey smell – as he examined the ruins of the room. It<br />

appeared Kane had been trying to refill the vaporiser when he’d<br />

succumbed. The schoolteacher’s gaze was fixed in death upon<br />

a single panel where condensation had completely peeled the<br />

fashionable green wallpaper away. Exposed to the moisture, the<br />

stain of Millicent Mayfield’s blood had brightened and spread.<br />

And Reginald Kane lay twisted on the floor, his lips as blue as the<br />

eyes which had once held Millicent in thrall.<br />

28

29<br />

The secret in<br />

the doll’s dress

Examination report<br />

Kate Douglas<br />

Case<br />

The secret in the doll’s dress<br />

Item<br />

Doll’s dress, c.1865<br />

Summary<br />

During the conservation condition assessment of this Victorian<br />

doll’s dress in 2006, it was noted that damage had caused two<br />

small sections of paper containing text (one handwritten, one<br />

printed) to become visible, indicating the existence of paper<br />

templates beneath the silk. The location of this text was recorded,<br />

the area photographed and the paper templates subsequently hidden<br />

by conservation repairs. In preparation for Fashion Detective analysis<br />

was carried out by textile conservators at the National Gallery of<br />

Victoria to determine if it was possible to ‘read’ what was written<br />

on these hidden paper templates.<br />

Unknown, England, Doll’s dress, c.1865 (detail of handwritten text taken during conservation assessment<br />

in 2006)<br />

Unknown, England, Doll’s dress, c.1865 (detail of printed text taken during conservation assessment in 2006)<br />

Unknown, England, Doll’s dress, c.1865<br />

Background information<br />

The maker of the doll’s dress used the traditional quilting method<br />

of English paper piecing when hand-stitching the dress. This method<br />

involves folding and basting a variety of silk fabrics around tiny<br />

diamond-shaped paper templates. The silk patches were then sewn<br />

together using fine whipstitches. Quilts made using this method often<br />

have the paper templates left in place, leading scholars to believe they<br />

were an intrinsic part of the quilts’ layering used to provide strength<br />

and warmth. 1 In support of this, analysis of historic quilts shows that<br />

when paper piecing wore out, it was sometimes replaced. 2<br />

Unknown, Australia/England, Patchwork cover, c.1890 (detail of the intact paper template, visible at back<br />

of quilt)<br />

The maker of the doll’s dress used the tumbling block quilt pattern,<br />

which was extremely popular in Britain at this time not only for<br />

making quilts, but also for producing small decorative items. 3 Another<br />

example of Victorian quilting in this exhibition is Patchwork Cover,<br />

c.1890, which was also made using tumbling block and paper piecing.<br />

Unlike the doll’s dress, which is fully lined, this quilt no longer<br />

has a lining and almost all of its templates are missing. Some small<br />

paper fragments, however, remain in seams, as well as one complete<br />

template with handwritten script.<br />

30

In the nineteenth century paper was an expensive commodity, and it<br />

was common practice for even the wealthiest households to re-use it.<br />

Because of the paper’s previous use, paper templates remaining within<br />

examples of patchwork can provide information regarding dates and<br />

sometimes a geographical location for the work. Papers found in other<br />

English quilts from this period have been recycled from ephemeral<br />

materials, such as school exercise books, ledgers, advertisements,<br />

newspapers and receipts. 4<br />

Process<br />

With the help of the NGV’s Photographic Services department, it<br />

was suggested that perhaps the best chance of ‘reading’ the paper was<br />

to transmit light through the doll’s dress, in the hope that this would<br />

show any dark areas of ink beneath the silk. The dress was carefully<br />

suspended so that light could shine through one side at a time. A<br />

photographic flash was positioned on one side of the dress, and the<br />

camera on the other to record the light shining through. The flash was<br />

set so that it was powerful enough to penetrate through the multiple<br />

layers of fabric, as well as the paper in between.<br />

This technique was also trialled in infra-red to see if it improved the<br />

readability of the text. An infra-red sensitive camera was used with an<br />

infra-red pass filter over the lens to block visible light. This particularly<br />

enhanced the readability of the typeset words, but not the handwriting.<br />

The transmitted light was strong enough to show a faint glow<br />

through the silk patches, and a few dark smudges became visible on<br />

the monitor. The camera focus was painstakingly adjusted through<br />

the various layers until the camera was focused on the paper layer.<br />

A number of eerie-looking printed and handwritten words became<br />

visible, clearly showing that a large number of the paper templates<br />

had been recycled from printed material.<br />

Transmitted light photograph in infra-red revealing the word ‘presence’ printed in letterpress<br />

Evidence<br />

Transmitted light photograph in infra-red revealing the word ‘GUILD’ printed in letterpress<br />

The printed characters are likely to be letterpress, a relief printing<br />

technique commonly used in the nineteenth century that may leave an<br />

indentation on paper. They are clearly defined, and perhaps a slight<br />

impression can be discerned from the initial photograph. The type<br />

is serif, with pronounced contrast between its thick and thin lines.<br />

Unfortunately the typeface could not be identified from the images.<br />

Some of the printed words are clearly discernible, such as the words<br />

‘GUILD’ and ‘Presence’. Other words are only partially readable.<br />

However, with uncanny convenience the date ‘1859’ can be clearly<br />

read on one of the printed paper templates. The typematter does<br />

Transmitted light photograph in infra-red revealing the date ‘1859’<br />

not seem dense enough to be a newspaper column – but this is a<br />

subjective assumption. The printed characters are more likely to be<br />

from another ephemeral source, such as an advertising flyer which<br />

might include a current date.<br />

31

Transmitted light photograph showing copperplate handwritting<br />

X-ray showing construction details including basting stitches, folds of silk patches and paper patches<br />

Many of the handwritten words could only be partially read: the text<br />

is quite large, is often fragmented and the ink is less dense than that<br />

of the printed words. The style is clearly copperplate, a neat round<br />

handwriting meticulously learnt by children in Victorian times, which<br />

is slanted and looped with thick and thin strokes created by differing<br />

pressures produced by the flexible metal pointed nib of a dip pen.<br />

Although it was not expected that x-radiology would differentiate<br />

between the carbon of the printing ink and the other materials in the<br />

dress, it was hoped that the differences in paper thickness created from<br />

the impression of the letterpress would reveal the text. This was not<br />

the case, but the x-ray does provide valuable information about the<br />

structure of the dress, including its basting stitches, folds of silk patches<br />

and the condition of the paper patches beneath. The x-ray indicates<br />

that the paper shows signs of wear but, after approximately 150 years,<br />

has not broken down as much as would be expected of groundwood<br />

newsprint, indicating that the paper was of good quality, which is<br />

typical of paper from the middle part of the nineteenth century.<br />

Thank you: John Payne, Senior Conservator, Painting, NGV (x-radiography);<br />

Narelle Wilson, Photographer, NGV (infra-red photography); David Harris,<br />

Paper Conservator, State Library of Victoria, Melbourne (advice on paper and typeface).<br />

NOTES<br />

1 Joanne Hackett, ‘X-radiography as a tool to examine the making and remaking of historic quilts’, V&A, ,<br />

accessed 1 March 2014.<br />

2 Sue Pritchford (ed.), Quilts 1700–1945, Queensland Art Gallery, Brisbane, and Victoria and Albert Museum, London,<br />

2013, p. 134.<br />

3 Jenny Manning, Australia’s Quilts: A Directory of Patchwork Treasures, AQD Press, Sydney, p. 198.<br />

4 Pritchford, p. 134.<br />

Conclusion<br />

Transmitted light and infra-red analysis revealed that many of the paper<br />

templates inside the doll’s dress contained printed words produced by<br />

both letterpress and copperplate techniques. We were fortunate to find<br />

the printed date of 1859 among a collection of words, which supports<br />

the catalogue dating of c.1865 and shows that the dress is unlikely to<br />

have been made before 1859. It is unknown, however, how long the<br />

dress took to make or how long the paper was stored before cutting<br />

into templates. This research has added a valuable layer of information<br />

about hidden components of the doll’s dress.<br />

32

PAPER<br />

PIECING<br />

It is exquisite. Pieced all over in thousands of little diamonds, each one perfectly<br />

pointed and embroidered with flowers. The dress shimmers with all the colours<br />

of the rainbow. It glows in the dullness of the cottage. Kitty can barely breathe.<br />

She lifts it gently from the box. The fabric is butter-soft, and whispers like silk.<br />

Lili Wilkinson

Lili Wilkinson<br />

xcuse me? Is anyone home?’<br />

The cottage is small and cramped and smells of mildew.<br />