Guidelines on metals and alloys used as food contact materials ...

Guidelines on metals and alloys used as food contact materials ...

Guidelines on metals and alloys used as food contact materials ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

COUNCIL OF EUROPE’S POLICY STATEMENTS<br />

CONCERNING MATERIALS AND ARTICLES<br />

INTENDED TO COME INTO CONTACT WITH FOODSTUFFS<br />

POLICY STATEMENT<br />

CONCERNING METALS AND ALLOYS<br />

TECHNICAL DOCUMENT<br />

GUIDELINES ON METALS AND ALLOYS<br />

USED AS FOOD CONTACT MATERIALS<br />

(13.02.2002)

TECHNICAL DOCUMENT<br />

GUIDELINES ON METALS AND ALLOYS<br />

USED AS FOOD CONTACT MATERIALS<br />

3

NOTE TO THE READER<br />

The <str<strong>on</strong>g>Guidelines</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> <strong>metals</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>alloys</strong> <strong>used</strong> <strong>as</strong> <strong>food</strong> c<strong>on</strong>tact <strong>materials</strong> are part of the Council of<br />

Europe’s policy statements c<strong>on</strong>cerning <strong>materials</strong> <strong>and</strong> articles intended to come into c<strong>on</strong>tact<br />

with <strong>food</strong>stuffs.<br />

The present document may be c<strong>on</strong>sulted <strong>on</strong> the Internet website of the Partial Agreement<br />

Department in the Social <strong>and</strong> Public Health Field:<br />

www.coe.fr/soc-sp<br />

For further informati<strong>on</strong>, ple<strong>as</strong>e c<strong>on</strong>tact:<br />

Dr Peter Baum<br />

Partial Agreement Department in<br />

the Social <strong>and</strong> Public Health Field<br />

Council of Europe<br />

Avenue de l’Europe<br />

F-67000 Str<strong>as</strong>bourg<br />

Tel. +33 (0)3 88 41 21 76<br />

E-mail: peter.baum@coe.int<br />

Fax +33 (0)3 88 41 27 32<br />

4

TABLE OF CONTENTS<br />

Page<br />

Part I - Council of Europe <strong>and</strong> <strong>food</strong> c<strong>on</strong>tact <strong>materials</strong><br />

1. Council of Europe........................................................................................... 7<br />

2. The Partial Agreement in the social <strong>and</strong> public health field............................. 7<br />

3. Council of Europe Committees in the public health field ................................. 8<br />

4. Terms of reference of the Committee of experts <strong>on</strong> <strong>materials</strong><br />

coming into c<strong>on</strong>tact with <strong>food</strong>......................................................................... 9<br />

5. Main t<strong>as</strong>ks of the Committee of experts <strong>on</strong> <strong>materials</strong> coming<br />

into c<strong>on</strong>tact with <strong>food</strong>..................................................................................... 10<br />

Part II - <str<strong>on</strong>g>Guidelines</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> <strong>metals</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>alloys</strong> <strong>used</strong> <strong>as</strong> <strong>food</strong> c<strong>on</strong>tact <strong>materials</strong><br />

General <str<strong>on</strong>g>Guidelines</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

1. Introducti<strong>on</strong> ..................................................................................................13<br />

2. Legal status of these guidelines <strong>and</strong> their update ......................................... 13<br />

3. Field of applicati<strong>on</strong> ....................................................................................... 14<br />

4. General requirements <strong>and</strong> recommendati<strong>on</strong>s ............................................... 16<br />

Specific <str<strong>on</strong>g>Guidelines</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

Aluminium .........................................................................................................23<br />

Chromium ..........................................................................................................27<br />

Copper ..............................................................................................................31<br />

Ir<strong>on</strong> ................................................................................................................... 35<br />

Lead.................................................................................................................. 37<br />

Manganese ...................................................................................................... 41<br />

Nickel ............................................................................................................... 43<br />

Silver ................................................................................................................ 47<br />

Tin .................................................................................................................... 49<br />

5

Specific <str<strong>on</strong>g>Guidelines</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

Titanium ........................................................................................................... 53<br />

Zinc ................................................................................................................... 55<br />

Alloys other than stainless steel ....................................................................... 57<br />

Stainless steel .................................................................................................. 61<br />

Appendix l – Metallic elements found <strong>as</strong> c<strong>on</strong>taminants <strong>and</strong> impurities ...............67<br />

Cadmium .......................................................................................................... 69<br />

Cobalt ............................................................................................................... 73<br />

Mercury ............................................................................................................ 75<br />

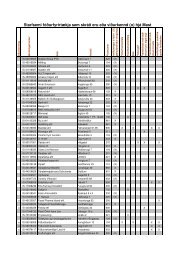

Appendix II – Comparisi<strong>on</strong> of the intakes of selected <strong>metals</strong> with their PTWI ... 77<br />

Appendix III – Natural elements’ c<strong>on</strong>tent of <strong>food</strong>stuffs ...................................... 81<br />

6

PART I<br />

COUNCIL OF EUROPE AND FOOD CONTACT MATERIALS<br />

1. Council of Europe<br />

The Council of Europe is a political organisati<strong>on</strong> which w<strong>as</strong> founded <strong>on</strong> 5 May 1949 by ten<br />

European countries in order to promote greater unity between its members. It now numbers 43<br />

member States 1 .<br />

The main aims of the Organisati<strong>on</strong> are to reinforce democracy, human rights <strong>and</strong> the rule of law<br />

<strong>and</strong> to develop comm<strong>on</strong> resp<strong>on</strong>ses to political, social, cultural <strong>and</strong> legal challenges in its<br />

member States. Since 1989 the Council of Europe h<strong>as</strong> integrated most of the countries of<br />

Central <strong>and</strong> E<strong>as</strong>tern Europe into its structures <strong>and</strong> supported them in their efforts to implement<br />

<strong>and</strong> c<strong>on</strong>solidate their political, legal <strong>and</strong> administrative reforms.<br />

The work of the Council of Europe h<strong>as</strong> led, to date, to the adopti<strong>on</strong> of over 170 European<br />

c<strong>on</strong>venti<strong>on</strong>s <strong>and</strong> agreements, which create the b<strong>as</strong>is for a comm<strong>on</strong> legal space in Europe. They<br />

include the European C<strong>on</strong>venti<strong>on</strong> <strong>on</strong> Human Rights (1950), the European Cultural C<strong>on</strong>venti<strong>on</strong><br />

(1954), the European Social Charter (1961), the European C<strong>on</strong>venti<strong>on</strong> <strong>on</strong> the Preventi<strong>on</strong> of<br />

Torture (1987) <strong>and</strong> the C<strong>on</strong>venti<strong>on</strong> <strong>on</strong> Human Rights <strong>and</strong> Bioethics (1997). Numerous<br />

recommendati<strong>on</strong>s <strong>and</strong> resoluti<strong>on</strong>s of the Committee of Ministers propose policy guidelines for<br />

nati<strong>on</strong>al governments.<br />

The Council of Europe h<strong>as</strong> its permanent headquarters in Str<strong>as</strong>bourg (France). By statute, it<br />

h<strong>as</strong> two c<strong>on</strong>stituent organs: the Committee of Ministers, composed of the Ministers of Foreign<br />

Affairs of the 43 member States, <strong>and</strong> the Parliamentary Assembly, comprising delegati<strong>on</strong>s from<br />

the 43 nati<strong>on</strong>al parliaments. The C<strong>on</strong>gress of Local <strong>and</strong> Regi<strong>on</strong>al Authorities of Europe<br />

represents the entities of local <strong>and</strong> regi<strong>on</strong>al self-government within the member States. A<br />

multinati<strong>on</strong>al European Secretariat serves these bodies <strong>and</strong> the intergovernmental committees.<br />

2. The Partial Agreement in the social <strong>and</strong> public health field<br />

Where a lesser number of member states of the Council of Europe wish to engage in some<br />

acti<strong>on</strong> in which not all their European partners desire to join, they can c<strong>on</strong>clude a ’Partial<br />

Agreement’ which is binding <strong>on</strong> themselves al<strong>on</strong>e.<br />

The Partial Agreement in the social <strong>and</strong> public health field w<strong>as</strong> c<strong>on</strong>cluded <strong>on</strong> this b<strong>as</strong>is in 1959.<br />

The are<strong>as</strong> of activity of the Partial Agreement in the social <strong>and</strong> public health field include two<br />

sectors:<br />

▪<br />

▪<br />

Protecti<strong>on</strong> of public health<br />

Rehabilitati<strong>on</strong> <strong>and</strong> integrati<strong>on</strong> of people with disabilities.<br />

1<br />

Albania, Andorra, Armenia, Austria, Azerbaijan, Belgium, Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, Czech Republic,<br />

Denmark, Est<strong>on</strong>ia, Finl<strong>and</strong>, France, Georgia, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Icel<strong>and</strong>, Irel<strong>and</strong>, Italy,<br />

Latvia, Liechtenstein, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, Moldova, The Netherl<strong>and</strong>s, Norway, Pol<strong>and</strong>,<br />

Portugal, Romania, Russian Federati<strong>on</strong>, San Marino, Slovak Republic, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden,<br />

Switzerl<strong>and</strong>, "the former Yugoslav Republic of Maced<strong>on</strong>ia", Turkey, Ukraine, United Kingdom of<br />

Great Britain <strong>and</strong> Northern Irel<strong>and</strong>.<br />

7

At present, the Partial Agreement in the public health field h<strong>as</strong> 18 member states 1 .<br />

The activities are entrusted to committees of experts, which are resp<strong>on</strong>sible to a steering<br />

committee for each area.<br />

The work of the Partial Agreement committees occ<strong>as</strong>i<strong>on</strong>ally results in the elaborati<strong>on</strong> of<br />

c<strong>on</strong>venti<strong>on</strong>s or agreements. The more usual outcome is the drawing-up of resoluti<strong>on</strong>s of<br />

member states, adopted by the Committee of Ministers. The resoluti<strong>on</strong>s should be c<strong>on</strong>sidered<br />

<strong>as</strong> statements of policy for nati<strong>on</strong>al policy-makers. Governments have actively participated in<br />

their formulati<strong>on</strong>. The delegates to the Partial Agreement committees are both experts in the<br />

field in questi<strong>on</strong> <strong>and</strong> resp<strong>on</strong>sible for the implementati<strong>on</strong> of government policy in their nati<strong>on</strong>al<br />

ministries.<br />

The procedure provides for c<strong>on</strong>siderable flexibility in that any state may reserve its positi<strong>on</strong> <strong>on</strong> a<br />

given point without thereby preventing the others from going ahead with what they c<strong>on</strong>sider<br />

appropriate. Another advantage is that the resoluti<strong>on</strong>s are readily susceptible to amendment<br />

should the need arise. Governments are furthermore called up<strong>on</strong> periodically to report <strong>on</strong> the<br />

implementati<strong>on</strong> of the recommended me<strong>as</strong>ures.<br />

A less formal procedure is the elaborati<strong>on</strong> of technical documents intended to serve <strong>as</strong> models<br />

for member states <strong>and</strong> industry.<br />

Bodies of the Partial Agreement in the social <strong>and</strong> public health field enjoy close co-operati<strong>on</strong><br />

with equivalent bodies in other internati<strong>on</strong>al instituti<strong>on</strong>s, in particular the Commissi<strong>on</strong> of the<br />

European Uni<strong>on</strong>. C<strong>on</strong>tact is also maintained with internati<strong>on</strong>al n<strong>on</strong>-governmental organisati<strong>on</strong>s<br />

(NGOs) <strong>and</strong> industry, working in similar or related fields.<br />

3. Council of Europe committees in the public health field<br />

▪<br />

▪<br />

Public Health Committee (Steering Committee)<br />

Committee of experts <strong>on</strong> <strong>materials</strong> coming into c<strong>on</strong>tact with <strong>food</strong><br />

Ad hoc Groups of the Committee of experts:<br />

- Ad hoc Group <strong>on</strong> safety evaluati<strong>on</strong><br />

- Ad hoc Group <strong>on</strong> recycled fibres (with industry participati<strong>on</strong>)<br />

- Ad hoc Group <strong>on</strong> test c<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong>s for paper <strong>and</strong> board<br />

(with industry participati<strong>on</strong>)<br />

- Ad hoc Group <strong>on</strong> tissue papers (with industry participati<strong>on</strong>)<br />

- Ad hoc Group <strong>on</strong> packaging inks (with industry participati<strong>on</strong>)<br />

- Ad hoc Group <strong>on</strong> coatings (with industry participati<strong>on</strong>)<br />

- Ad hoc Group <strong>on</strong> cork (with industry participati<strong>on</strong>)<br />

- Ad hoc Group <strong>on</strong> rubber (with industry participati<strong>on</strong>)<br />

▪<br />

Committee of experts <strong>on</strong> nutriti<strong>on</strong>, <strong>food</strong> safety <strong>and</strong> c<strong>on</strong>sumer health<br />

Ad hoc Groups of the Committee of experts:<br />

- Ad hoc Group <strong>on</strong> functi<strong>on</strong>al <strong>food</strong> (with industry participati<strong>on</strong>)<br />

- Ad hoc Group <strong>on</strong> nutriti<strong>on</strong> in hospitals<br />

- Ad hoc Group <strong>on</strong> stored product protecti<strong>on</strong><br />

1<br />

Austria, Belgium, Cyprus, Denmark, Finl<strong>and</strong>, France, Germany, Irel<strong>and</strong>, Italy, Luxembourg, The<br />

Netherl<strong>and</strong>s, Norway, Portugal, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerl<strong>and</strong>, United Kingdom of Great<br />

Britain <strong>and</strong> Northern Irel<strong>and</strong>.<br />

8

▪<br />

Committee of experts <strong>on</strong> flavouring substances<br />

Ad hoc Group of the Committee of experts:<br />

- Ad hoc Group <strong>on</strong> active principles<br />

▪<br />

Committee of experts <strong>on</strong> cosmetic products<br />

Ad hoc Group of the Committee of experts:<br />

- Ad hoc Group <strong>on</strong> active ingredients<br />

▪<br />

▪<br />

Committee of experts <strong>on</strong> pharmaceutical questi<strong>on</strong>s<br />

Committee of experts <strong>on</strong> medicines subject to prescripti<strong>on</strong><br />

4. Terms of reference of the Committee of experts <strong>on</strong> <strong>materials</strong> coming into<br />

c<strong>on</strong>tact with <strong>food</strong><br />

The overall aim of the Council of Europe Partial Agreement public health activities is to raise<br />

the level of health protecti<strong>on</strong> of c<strong>on</strong>sumers <strong>and</strong> <strong>food</strong> safety in its widest sense.<br />

The terms of reference of the Committee of experts <strong>on</strong> <strong>materials</strong> coming into c<strong>on</strong>tact with <strong>food</strong><br />

(hereafter called ‘Committee of experts’) are part of the overall aim of these activities <strong>and</strong> are<br />

related to precise problems c<strong>on</strong>cerning <strong>food</strong> c<strong>on</strong>tact <strong>materials</strong> <strong>and</strong> articles.<br />

The representatives of the Partial Agreement member states <strong>and</strong> delegates of the Committee<br />

of experts are both experts in the field of <strong>food</strong> c<strong>on</strong>tact <strong>materials</strong> <strong>and</strong> resp<strong>on</strong>sible for the<br />

implementati<strong>on</strong> of government policies in their nati<strong>on</strong>al ministries.<br />

The Commissi<strong>on</strong> of the European Uni<strong>on</strong> h<strong>as</strong> a particular status of participati<strong>on</strong> within the<br />

Committee of Experts.<br />

European industry branch <strong>as</strong>sociati<strong>on</strong>s are not entitled to send representatives to the meetings<br />

of the Committee of experts. They may be represented at the level of the Ad hoc Groups,<br />

which are advisory bodies to the Committee of experts. Ad hoc Groups are not entitled to take<br />

formal decisi<strong>on</strong>s.<br />

Hearings are regularly organised between the Committee of experts <strong>and</strong> the European industry<br />

branch <strong>as</strong>sociati<strong>on</strong>s <strong>on</strong> specific questi<strong>on</strong>s related to the work programme.<br />

9

5. Main t<strong>as</strong>ks of the Committee of experts <strong>on</strong> <strong>materials</strong> coming into c<strong>on</strong>tact with <strong>food</strong><br />

▪<br />

Elaborati<strong>on</strong> of resoluti<strong>on</strong>s<br />

Resoluti<strong>on</strong>s elaborated by the Committee of experts are approved by the Public Health<br />

Committee <strong>and</strong> adopted by the Committee of Ministers 1 ;<br />

They have to be c<strong>on</strong>sidered <strong>as</strong> statements of policy or statements for nati<strong>on</strong>al policy-makers of<br />

the Partial Agreement member states to be taken into account in the nati<strong>on</strong>al laws <strong>and</strong><br />

regulati<strong>on</strong>s <strong>on</strong> <strong>materials</strong> <strong>and</strong> articles intended to come into c<strong>on</strong>tact with <strong>food</strong>stuffs, with the<br />

view of harm<strong>on</strong>ising regulati<strong>on</strong>s at European level.<br />

They lay down the field of applicati<strong>on</strong>, the specificati<strong>on</strong>s <strong>and</strong> the restricti<strong>on</strong>s c<strong>on</strong>cerning the<br />

manufacture of <strong>materials</strong> <strong>and</strong> articles intended to come into c<strong>on</strong>tact with <strong>food</strong>stuffs.<br />

If necessary, they are amended in order to update their c<strong>on</strong>tent.<br />

▪<br />

Elaborati<strong>on</strong> of technical documents<br />

Technical documents elaborated by the Committee of experts <strong>and</strong>/or Ad hoc Groups, are<br />

approved by the Committee of experts <strong>and</strong> adopted by the Public Health Committee. They are<br />

not submitted to the Committee of Ministers.<br />

They have to be c<strong>on</strong>sidered <strong>as</strong> models <strong>and</strong> requirements to be taken into account in the<br />

c<strong>on</strong>text of resoluti<strong>on</strong>s or <strong>as</strong> models <strong>and</strong> requirements al<strong>on</strong>e for the implementati<strong>on</strong> of nati<strong>on</strong>al<br />

policies.<br />

They provide practical guidance for the applicati<strong>on</strong> of resoluti<strong>on</strong>s <strong>and</strong>/or lay down technical<br />

<strong>and</strong>/or scientific specificati<strong>on</strong>s for the manufacture of <strong>materials</strong> <strong>and</strong> articles intended to come<br />

into c<strong>on</strong>tact with <strong>food</strong>stuffs.<br />

If necessary, they are amended in the light of technical <strong>and</strong>/or scientific developments of<br />

manufacturing processes <strong>and</strong> techniques of <strong>materials</strong> intended to come into c<strong>on</strong>tact with<br />

<strong>food</strong>stuffs.<br />

Typical examples of technical documents are:<br />

List of substances for the manufacture of <strong>materials</strong> <strong>and</strong> articles intended to come into<br />

c<strong>on</strong>tact with <strong>food</strong>stuffs<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Guidelines</str<strong>on</strong>g> c<strong>on</strong>cerning the manufacture of <strong>materials</strong> <strong>and</strong> articles intended to<br />

come into c<strong>on</strong>tact with <strong>food</strong>stuffs<br />

1<br />

The Committee of Ministers is the Council of Europe’s political decisi<strong>on</strong>-making body. It<br />

comprises the Ministers for Foreign Affairs of the forty-three member states, or their permanent<br />

diplomatic representatives in Str<strong>as</strong>bourg. It m<strong>on</strong>itors member states’ compliance with their<br />

undertakings. Resoluti<strong>on</strong>s of the Partial Agreement in the social <strong>and</strong> public health field are<br />

adopted by the Committee of Ministers restricted to Representatives of the member states of the<br />

Partial Agreement.<br />

10

Good manufacturing practices (GMP) c<strong>on</strong>cerning the manufacture of <strong>materials</strong> <strong>and</strong><br />

articles intended to come into c<strong>on</strong>tact with <strong>food</strong>stuffs<br />

Test c<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong>s <strong>and</strong> methods of analysis for the manufacture of <strong>materials</strong> <strong>and</strong><br />

articles intended to come into c<strong>on</strong>tact with <strong>food</strong>stuffs<br />

Practical guides for users of resoluti<strong>on</strong>s <strong>and</strong> technical documents<br />

▪<br />

Elaborati<strong>on</strong> of opini<strong>on</strong>s<br />

On request by the Committee of Ministers <strong>and</strong>/or the Public Health Committee, the Committee<br />

of experts elaborates opini<strong>on</strong>s <strong>on</strong> specific questi<strong>on</strong>s related to <strong>food</strong> c<strong>on</strong>tact <strong>materials</strong> <strong>and</strong><br />

articles which are submitted for adopti<strong>on</strong> to its superior bodies.<br />

11

PART II<br />

GUIDELINES ON METALS AND ALLOYS USED<br />

AS FOOD CONTACT MATERIALS<br />

1. Introducti<strong>on</strong><br />

Metals <strong>and</strong> <strong>alloys</strong> are <strong>used</strong> <strong>as</strong> <strong>food</strong> c<strong>on</strong>tact <strong>materials</strong>, mainly in processing<br />

equipment,c<strong>on</strong>tainers <strong>and</strong> household utensils but also in foils for wrapping <strong>food</strong>stuffs. They play<br />

a role <strong>as</strong> a safety barrier between the <strong>food</strong> <strong>and</strong> the exterior. They are often covered by a surface<br />

coating, which reduces the migrati<strong>on</strong> in <strong>food</strong>stuffs. When they are not covered these <strong>food</strong><br />

c<strong>on</strong>tact <strong>materials</strong> can give rise to migrati<strong>on</strong> of metal i<strong>on</strong>s into the <strong>food</strong>stuffs <strong>and</strong> therefore could<br />

either endanger human health if the total c<strong>on</strong>tent of the <strong>metals</strong> exceeds the sanitary<br />

recommended exposure limits, if any, or bring about an unacceptable change in the<br />

compositi<strong>on</strong> of the <strong>food</strong>stuffs or a deteriorati<strong>on</strong> in their organoleptic characteristics. Therefore it<br />

w<strong>as</strong> deemed necessary to establish these guidelines to regulate this sector.<br />

These <str<strong>on</strong>g>Guidelines</str<strong>on</strong>g> do not deal with the following issues:<br />

Exposure through inhalati<strong>on</strong>, skin c<strong>on</strong>tact etc. The guidelines <strong>on</strong>ly cover the oral intake of<br />

metallic elements. Inhalati<strong>on</strong>, skin c<strong>on</strong>tact etc. is not covered by the guidelines even though<br />

there may be toxicological implicati<strong>on</strong>s c<strong>on</strong>nected to these exposures<br />

Nutriti<strong>on</strong>al <strong>as</strong>pects, <strong>as</strong> the guidelines deal with the elements from the migrati<strong>on</strong> point of view<br />

<strong>and</strong> thus c<strong>on</strong>sider the elements <strong>as</strong> being c<strong>on</strong>taminants, even though some of them are<br />

essential elements.<br />

1.1. Co-operati<strong>on</strong> with industry<br />

These <str<strong>on</strong>g>Guidelines</str<strong>on</strong>g> have been elaborated by the Council of Europe Committee of experts <strong>on</strong><br />

<strong>materials</strong> coming into c<strong>on</strong>tact with <strong>food</strong>, after c<strong>on</strong>sultati<strong>on</strong> of the representatives of the<br />

following professi<strong>on</strong>al <strong>as</strong>sociati<strong>on</strong>s:<br />

APEAL (The Associati<strong>on</strong> of European Producers of Steel for Packaging),<br />

BCCCA (The Biscuit, Cake, Chocolate & C<strong>on</strong>fecti<strong>on</strong>ery Alliance),<br />

EUROFER (European C<strong>on</strong>federati<strong>on</strong> of Ir<strong>on</strong> <strong>and</strong> Steel Industries),<br />

EUROMETAUX (European Associati<strong>on</strong> of the N<strong>on</strong> Ferrous Metals Industry),<br />

EIMAC (European Industry Metals <strong>and</strong> Alloys Cl<strong>as</strong>sificati<strong>on</strong> Group), <strong>and</strong><br />

SEFEL (European Metal Packaging Manufacturers Associati<strong>on</strong> (Société Européenne de<br />

Fabricants d'Emballage Métallique léger).<br />

2. Legal status of the <str<strong>on</strong>g>Guidelines</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>and</strong> their update<br />

These <str<strong>on</strong>g>Guidelines</str<strong>on</strong>g> are not legally binding but are c<strong>on</strong>sidered by the member states<br />

represented in the Council of Europe Committee of experts <strong>on</strong> <strong>food</strong> c<strong>on</strong>tact <strong>materials</strong> <strong>as</strong> a<br />

reference document to <strong>as</strong>sist enforcement authorities, industry <strong>and</strong> users to ensure<br />

13

compliance of <strong>metals</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>alloys</strong> <strong>used</strong> for <strong>food</strong> c<strong>on</strong>tact <strong>materials</strong> with the provisi<strong>on</strong>s of Article<br />

2.2 of Directive 89/109/EEC. <str<strong>on</strong>g>Guidelines</str<strong>on</strong>g> are c<strong>on</strong>sidered <strong>as</strong> a less formal procedure than<br />

resoluti<strong>on</strong>s. They are ‘Technical documents’ which are approved by the Committee of<br />

experts. These <str<strong>on</strong>g>Guidelines</str<strong>on</strong>g> will be updated by the Committee of experts in the light of<br />

technical <strong>and</strong>/or scientific developments.<br />

3. Field of applicati<strong>on</strong><br />

These <str<strong>on</strong>g>Guidelines</str<strong>on</strong>g> apply to any type of <strong>materials</strong> <strong>and</strong> articles, manufactured or imported in<br />

Europe, intended to come into c<strong>on</strong>tact with <strong>food</strong>stuffs made completely or partly of <strong>metals</strong> <strong>and</strong><br />

<strong>alloys</strong> (“metallic <strong>materials</strong>”), i.e. household utensils <strong>and</strong> processing equipment like <strong>food</strong><br />

processors, transportati<strong>on</strong> b<strong>and</strong>s, wrapping, c<strong>on</strong>tainers, pots, stirring pots, knives, forks, spo<strong>on</strong>s<br />

etc.<br />

3.1. Definiti<strong>on</strong> of <strong>metals</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>alloys</strong><br />

Metals are usually characterised <strong>on</strong> the b<strong>as</strong>is of their chemical <strong>and</strong> physical properties in the<br />

solid state. Metals are the cl<strong>as</strong>s of <strong>materials</strong> linked <strong>on</strong> an atomic scale by the metallic b<strong>on</strong>d. The<br />

metallic b<strong>on</strong>d may be described <strong>as</strong> an array of positive metallic i<strong>on</strong>s forming l<strong>on</strong>g-range crystal<br />

lattices in which valency electr<strong>on</strong>s are shared comm<strong>on</strong>ly throughout the structure. Such<br />

structures give rise to the following properties typical of the metallic state (Vouk, 1986):<br />

High reflectivity which is resp<strong>on</strong>sible for the characteristic metallic lustre<br />

High electrical c<strong>on</strong>ductivity which decre<strong>as</strong>es with incre<strong>as</strong>ing temperature<br />

High thermal c<strong>on</strong>ductivity<br />

Mechanical properties such <strong>as</strong> strength <strong>and</strong> ductility<br />

Metallic <strong>alloys</strong> are composed of two or more metallic elements. A more specific definiti<strong>on</strong> of<br />

<strong>alloys</strong> is given in the separate guideline <strong>on</strong> <strong>alloys</strong>.<br />

3.2. Metals <strong>and</strong> <strong>alloys</strong> covered by the <str<strong>on</strong>g>Guidelines</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

The following metallic <strong>materials</strong> are covered by these <str<strong>on</strong>g>Guidelines</str<strong>on</strong>g>:<br />

Aluminium<br />

Chromium<br />

Copper<br />

Ir<strong>on</strong><br />

Lead<br />

Manganese<br />

Nickel<br />

Silver<br />

Tin<br />

Titanium<br />

Zinc<br />

Stainless<br />

Other <strong>alloys</strong><br />

14

The <str<strong>on</strong>g>Guidelines</str<strong>on</strong>g> also cover::<br />

Cadmium<br />

Cobalt<br />

Mercury<br />

because these <strong>metals</strong> are present <strong>as</strong> impurities or c<strong>on</strong>taminant in some metallic <strong>materials</strong> <strong>and</strong>,<br />

therefore, they can migrate in <strong>food</strong>stuffs (see Appendix 1).<br />

Furthermore, antim<strong>on</strong>y, arsenic, barium, molybdenum, thallium, <strong>and</strong> magnesium could be<br />

addressed in Appendix I at a later stage.<br />

A guideline for beryllium h<strong>as</strong> been c<strong>on</strong>sidered. However, <strong>as</strong> beryllium w<strong>as</strong> found <strong>on</strong>ly to be<br />

<strong>used</strong> in copper beryllium <strong>alloys</strong> in metal mould tools for making pl<strong>as</strong>tic c<strong>on</strong>tainers <strong>and</strong> <strong>as</strong> no<br />

transfer of beryllium to the pl<strong>as</strong>tic h<strong>as</strong> been found it w<strong>as</strong> c<strong>on</strong>sidered unnecessary to establish a<br />

guideline for beryllium.<br />

3.3. Metals <strong>and</strong> <strong>alloys</strong> not covered by the <str<strong>on</strong>g>Guidelines</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

These <str<strong>on</strong>g>Guidelines</str<strong>on</strong>g> do not cover the following <strong>materials</strong> which may c<strong>on</strong>tribute to the intake of<br />

<strong>metals</strong>:<br />

Ceramics, crystal gl<strong>as</strong>s, printing inks, lacquers, aids for polymerisati<strong>on</strong> <strong>and</strong> other types of<br />

<strong>materials</strong>, which are either covered by specific legislati<strong>on</strong> in the EU or by Council of Europe<br />

resoluti<strong>on</strong>s. However, if <strong>metals</strong> are migrating from these <strong>materials</strong> into <strong>food</strong>stuffs this<br />

c<strong>on</strong>tributi<strong>on</strong> should also be c<strong>on</strong>sidered in the overall evaluati<strong>on</strong> of the metal c<strong>on</strong>tent of the<br />

final <strong>food</strong>stuffs <strong>and</strong> the total exposure.<br />

Any special requirements for pipelines for drinking water <strong>as</strong> drinking water is of special<br />

c<strong>on</strong>cern <strong>and</strong> is covered by separate internati<strong>on</strong>al legislati<strong>on</strong>. Furthermore, drinking water is<br />

not cl<strong>as</strong>sified <strong>as</strong> a <strong>food</strong>stuff in all member states.<br />

Those metallic <strong>materials</strong> which are covered by a layer of surface coatings able to c<strong>on</strong>stitute a<br />

“functi<strong>on</strong>al barrier” to the migrati<strong>on</strong> of the <strong>metals</strong> into the <strong>food</strong>stuffs thereby reducing the<br />

potential risk of migrati<strong>on</strong> of the metal.<br />

Toys. Even though toys are often found in breakf<strong>as</strong>t cereals etc. in direct <strong>food</strong> c<strong>on</strong>tact, the<br />

guidelines do not cover migrati<strong>on</strong> from toys.<br />

Active packaging or other active <strong>food</strong> c<strong>on</strong>tact articles. Active packaging is here defined <strong>as</strong> a<br />

<strong>food</strong> c<strong>on</strong>tact material or article, which does more than simply provide a barrier to outside<br />

influence. It can c<strong>on</strong>trol, <strong>and</strong> even react to, events taking place inside the package. Some<br />

articles for <strong>food</strong> c<strong>on</strong>tact are <strong>used</strong> with an intended migrati<strong>on</strong> of the <strong>metals</strong> into the <strong>food</strong>stuff.<br />

The migrati<strong>on</strong> is intended due to some effects of the <strong>metals</strong> in the <strong>food</strong>stuffs. This is the c<strong>as</strong>e for<br />

copper in cheese-making <strong>and</strong> for tin in some canned <strong>food</strong>stuffs. The use of <strong>metals</strong> with an<br />

intenti<strong>on</strong>al migrati<strong>on</strong> corresp<strong>on</strong>ds to the use of <strong>food</strong> additives or active packaging.<br />

These <strong>materials</strong> all c<strong>on</strong>tribute to the intake of <strong>metals</strong> <strong>and</strong> their c<strong>on</strong>tributi<strong>on</strong> to the total oral<br />

intake should be taken into account in the health evaluati<strong>on</strong> (see also § 4.4). However, these<br />

guidelines <strong>on</strong>ly cover <strong>materials</strong> <strong>and</strong> articles made exclusively of <strong>metals</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>alloys</strong>.<br />

15

4. General requirements <strong>and</strong> recommendati<strong>on</strong>s<br />

4.1. Health <strong>as</strong>pects<br />

In compliance with Article 2 of Directive 89/109/CEE metallic <strong>materials</strong> under normal <strong>and</strong><br />

foreseeable c<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong>s, should meet the following c<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong>s:<br />

They should be manufactured in accordance with good manufacturing practice <strong>and</strong> they should<br />

not transfer their c<strong>on</strong>stituents to <strong>food</strong>stuffs in quantities, which could:<br />

endanger human health<br />

bring about unacceptable change in the compositi<strong>on</strong> of the <strong>food</strong>stuffs or a deteriorati<strong>on</strong> in the<br />

organoleptic characteristics thereof.<br />

It must be stressed that the rele<strong>as</strong>e of a substance through migrati<strong>on</strong> should be reduced <strong>as</strong> low<br />

<strong>as</strong> re<strong>as</strong><strong>on</strong>ably achievable not <strong>on</strong>ly for health re<strong>as</strong><strong>on</strong>s but also to maintain the integrity of the<br />

<strong>food</strong>stuffs in c<strong>on</strong>tact.<br />

Where specific migrati<strong>on</strong> limits have been, or can be set, these limits should be fulfilled taking<br />

into account also the c<strong>on</strong>tributi<strong>on</strong> of the natural presence of <strong>metals</strong> in <strong>food</strong>stuffs. Where<br />

specific migrati<strong>on</strong> limits have not been set the levels of migrati<strong>on</strong> into <strong>food</strong>stuffs should be<br />

<strong>as</strong>sessed in relati<strong>on</strong> to health evaluati<strong>on</strong>s carried out by recognised scientific bodies where<br />

available, <strong>and</strong> in particular take account of dietary exposure including the natural presence of<br />

<strong>metals</strong> in <strong>food</strong>stuffs (see also § 4.4).<br />

Where necessary manufacturers of <strong>metals</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>alloys</strong> which are <strong>used</strong> in c<strong>on</strong>tact with <strong>food</strong>stuffs<br />

should provide guidance <strong>on</strong> <strong>as</strong>pects of manufacture, e.g. compositi<strong>on</strong>al limits, or <strong>as</strong>pects of use,<br />

which affect chemical migrati<strong>on</strong>. In particular the temperature <strong>and</strong> storage time is known to<br />

influence the migrati<strong>on</strong> of c<strong>on</strong>stituents of packaging <strong>materials</strong> into certain types of <strong>food</strong>stuff.<br />

Producers should label products with guidance to use. The labelling could include for instance<br />

restricted use for storage of str<strong>on</strong>gly acidic or salty <strong>food</strong>stuffs. The labelling could also include<br />

guidance <strong>on</strong> temperature storage of wet <strong>food</strong> in order to minimise migrati<strong>on</strong>. The labelling could<br />

be “Should be kept below 5 o C if the <strong>food</strong> will remain packaged for l<strong>on</strong>ger than 24 hours”. These<br />

labelling requirements would not be relevant for canned <strong>food</strong>.<br />

Remark: It should be recognised that industrial use <strong>and</strong> household use of <strong>materials</strong> for <strong>food</strong><br />

c<strong>on</strong>tact might vary greatly. Industrial envir<strong>on</strong>ment normally implies process c<strong>on</strong>trol, repeated<br />

use of the same equipment according to st<strong>and</strong>ard c<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong>s, selecti<strong>on</strong> <strong>and</strong> qualificati<strong>on</strong> of<br />

the <strong>food</strong> c<strong>on</strong>tact material (equipment or packaging) for a given <strong>food</strong>stuff <strong>and</strong> use, possible<br />

liability of the manufacturer in c<strong>as</strong>e of damage to c<strong>on</strong>sumers. Household use normally<br />

implies a wide range of <strong>food</strong>stuffs <strong>and</strong> c<strong>on</strong>tact c<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong>s, unc<strong>on</strong>trolled use of utensils limited<br />

<strong>on</strong>ly by c<strong>on</strong>cepts such <strong>as</strong> “current practice” or re<strong>as</strong><strong>on</strong>ably foreseeable use c<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong>s.<br />

Therefore, labelling with guidance of use from the producer to the c<strong>on</strong>sumer could limit<br />

inappropriate use of the <strong>food</strong> c<strong>on</strong>tact <strong>materials</strong>.<br />

4.2. Hygienic <strong>as</strong>pects<br />

Materials for <strong>food</strong> c<strong>on</strong>tact should comply with chapter V in the annex of Directive 93/43/EEC<br />

<strong>on</strong> the hygiene of <strong>food</strong>stuffs. Chapter V c<strong>on</strong>cerns equipment requirements <strong>and</strong> states the<br />

following:<br />

16

″All articles, fittings <strong>and</strong> equipment with which <strong>food</strong> comes into c<strong>on</strong>tact shall be kept clean<br />

<strong>and</strong>:<br />

(a) be so c<strong>on</strong>structed, be of such <strong>materials</strong> <strong>and</strong> be kept in such good order, repair <strong>and</strong><br />

c<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong> <strong>as</strong> to minimize any risk of c<strong>on</strong>taminati<strong>on</strong> of the <strong>food</strong>;<br />

(b) With the excepti<strong>on</strong> of n<strong>on</strong>-returnable c<strong>on</strong>tainers <strong>and</strong> packaging, be so c<strong>on</strong>structed, be of<br />

such <strong>materials</strong> <strong>and</strong> be kept in such good order, repair <strong>and</strong> c<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong> <strong>as</strong> to enable them to<br />

be kept thoroughly cleaned <strong>and</strong>, where necessary, disinfected, sufficient for the purposes<br />

intended;<br />

(c) be installed in such a manner <strong>as</strong> to allow adequate cleaning of the surrounding area.″<br />

4.3. Migrati<strong>on</strong> testing <strong>as</strong>pects<br />

In order to enforce the principle of inertness, the level of migrati<strong>on</strong> of the <strong>metals</strong> into the<br />

<strong>food</strong>stuffs should be determined in the worst foreseable c<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong>s, taking into account the<br />

natural c<strong>on</strong>tent in the metal of the <strong>food</strong>stuffs itself. Only this evaluati<strong>on</strong> can be <strong>used</strong> in order to<br />

establish the compliance with these guidelines.<br />

However, in order to evaluate the maximum potential rele<strong>as</strong>e of the <strong>metals</strong>, in principle, the<br />

migrati<strong>on</strong> testing described in the Appendix of the Directive 97/48/EC is recommended with the<br />

excepti<strong>on</strong> of acidic <strong>food</strong>stuffs. In fact, for acidic <strong>food</strong>stuffs, pending the selecti<strong>on</strong> of an<br />

appropriate test medium 1 , the test in <strong>food</strong>stuffs itself should be carried out otherwise the<br />

phenomen<strong>on</strong> of corrosi<strong>on</strong> may be produced .<br />

The use of validated or the generally recognised reference method is recommended for the<br />

determinati<strong>on</strong> of the c<strong>on</strong>tent of the <strong>metals</strong> in <strong>food</strong>stuffs or in <strong>food</strong> simulants. However, the<br />

preparati<strong>on</strong> of these methods is outside the scope of these guidelines.<br />

4.4. Health evaluati<strong>on</strong> <strong>as</strong>pects<br />

The health evaluati<strong>on</strong>s menti<strong>on</strong>ed in these <str<strong>on</strong>g>Guidelines</str<strong>on</strong>g> are related <strong>on</strong>ly to oral exposure <strong>and</strong><br />

therefore they do not take into c<strong>on</strong>siderati<strong>on</strong> other routes of exposure (inhalati<strong>on</strong>, dermal etc.).<br />

It is important to notice that the bioavailability <strong>and</strong> toxicity of a metal may depend <strong>on</strong> the metal<br />

compound or i<strong>on</strong>ic species present (Florence <strong>and</strong> Batley, 1980). Usually, the knowledge <strong>on</strong><br />

speciati<strong>on</strong> in relati<strong>on</strong> to migrati<strong>on</strong> <strong>and</strong> the toxicity of the individual relevant metal compounds is<br />

limited. Chemical speciati<strong>on</strong> may be defined <strong>as</strong> the determinati<strong>on</strong> of the individual<br />

c<strong>on</strong>centrati<strong>on</strong>s of the various chemical forms of an element which together make up the total<br />

c<strong>on</strong>centrati<strong>on</strong> of that element in a sample (Florence <strong>and</strong> Batley, 1980). In the c<strong>as</strong>e of metal<br />

toxicity, it is in most c<strong>as</strong>es accepted that the free (hydrated) metal i<strong>on</strong> is the most toxic form,<br />

where<strong>as</strong> str<strong>on</strong>gly complexed bound metal is much less toxic (Florence <strong>and</strong> Batley, 1980).<br />

However, an excepti<strong>on</strong> to this is mercury.<br />

Any risk <strong>as</strong>sessment of a substance which can endanger human health, e.g. <strong>metals</strong>, should<br />

cover exposure from all sources through oral uptake, including migrati<strong>on</strong> from <strong>food</strong> c<strong>on</strong>tact<br />

<strong>materials</strong> <strong>and</strong>, if available, other sources of <strong>food</strong> c<strong>on</strong>taminati<strong>on</strong>. Also the natural c<strong>on</strong>tent of<br />

<strong>metals</strong> in the <strong>food</strong>stuffs should be c<strong>on</strong>sidered (see Table in Appendix III).<br />

1<br />

A research is <strong>on</strong>going in the Nehring Institute to select a test medium more appropriate than the<br />

acetic acid 3% <strong>used</strong> in the p<strong>as</strong>t. Further research in the field of the selecti<strong>on</strong> of more appropriate<br />

test media are recommended.<br />

17

In principle, the maximum quantity of <strong>metals</strong> which can be absorbed by man from all sources<br />

should not exceed daily or weekly the TDI’s <strong>and</strong> the PTWI’s (multiplied by a body weight of 60<br />

kg) established by JECFA or the Scientific Committee for Food of the EU (SCF) or by other<br />

internati<strong>on</strong>al bodies. In Appendix II the existing JECFA PTWI’s <strong>and</strong> TDI’s have been listed.<br />

However, it should be stressed that the exceeding of these above-menti<strong>on</strong>ed sanitary limit<br />

values should be c<strong>on</strong>sidered <strong>as</strong> n<strong>on</strong>-compliant acti<strong>on</strong> (i.e. acti<strong>on</strong> not in compliance with the<br />

principle of inertness) <strong>and</strong> not necessarily <strong>as</strong> an acti<strong>on</strong> to endanger human health. In fact, to<br />

determine whether the PTWI or TDI is exceeded it is advisable to c<strong>on</strong>sider c<strong>on</strong>tributi<strong>on</strong> of the<br />

metal in <strong>food</strong>stuffs <strong>and</strong> the dietary habits, together with the level of migrati<strong>on</strong>. Moreover, it<br />

should be reminded that JECFA h<strong>as</strong> stated that “short-term exposure to levels exceeding the<br />

PTWI is not a cause for c<strong>on</strong>cern, provided the individual’s intake averaged over l<strong>on</strong>ger periods<br />

of time does not exceed the level set”.<br />

If there is a lack of internati<strong>on</strong>al sanitary limit values, it is recommended to apply the method<br />

currently <strong>used</strong> by internati<strong>on</strong>al bodies in the risk <strong>as</strong>sessment.<br />

4.5. Other related <strong>as</strong>pects<br />

The technical specificati<strong>on</strong>s for metallic <strong>materials</strong> set out in the European St<strong>and</strong>ard EN ISO<br />

8442-1 should be also taken into account.<br />

It would be too overwhelming to menti<strong>on</strong> all related work being carried out c<strong>on</strong>cerning either<br />

migrati<strong>on</strong>, migrati<strong>on</strong> testing or toxicological evaluati<strong>on</strong>s of <strong>metals</strong> or <strong>alloys</strong>. However, the work<br />

<strong>on</strong> evaluati<strong>on</strong> <strong>and</strong> c<strong>on</strong>trol of risks of existing substances should be menti<strong>on</strong>ed. This work is<br />

b<strong>as</strong>ed in the EU Council Regulati<strong>on</strong> 793/93/EEC of March 23, 1993 (L84 p. 1-75) <strong>and</strong> involves<br />

nickel, chrome <strong>and</strong> zinc am<strong>on</strong>g others.<br />

4.5.1. Corrosi<strong>on</strong><br />

Corrosi<strong>on</strong> is a phenomen<strong>on</strong> in which, in the presence of moisture <strong>and</strong> oxygen, the metal<br />

undergoes an electrochemical reacti<strong>on</strong> with comp<strong>on</strong>ents of the surrounding medium. In the<br />

simple c<strong>as</strong>e of uniform corrosi<strong>on</strong>, this reacti<strong>on</strong> results in the formati<strong>on</strong> of compounds of the<br />

metal (e.g. hydroxides) <strong>on</strong> the surface of the metal. The rate at which corrosi<strong>on</strong> proceeds will<br />

depend in part <strong>on</strong> the compositi<strong>on</strong> of the aqueous medium: corrosi<strong>on</strong> of ir<strong>on</strong> in very pure water<br />

will be c<strong>on</strong>siderably slower than in water which c<strong>on</strong>tains, for example, acids or salts. The rate<br />

of corrosi<strong>on</strong> depends also <strong>on</strong> the solubility of the formed compounds in the medium, <strong>and</strong> their<br />

rate of removal. Thus, for example, formed compounds may be removed rapidly in a flowing<br />

aqueous medium, <strong>and</strong> the corrosi<strong>on</strong> rate will be high. In a static medium, the rate of corrosi<strong>on</strong><br />

will be moderated <strong>as</strong> the i<strong>on</strong>ic c<strong>on</strong>centrati<strong>on</strong> of the surrounding medium incre<strong>as</strong>es. Corrosi<strong>on</strong><br />

products formed in the atmosphere are more or less adherent e.g. rust <strong>on</strong> ir<strong>on</strong>, verdigris <strong>on</strong><br />

copper. Rust is essentially hydrated ferric oxide which usually also c<strong>on</strong>tains some ferrous oxide<br />

<strong>and</strong> may c<strong>on</strong>tain ir<strong>on</strong> carb<strong>on</strong>ates <strong>and</strong>/or sulfates. Similarly, verdigris c<strong>on</strong>sists mainly of b<strong>as</strong>ic<br />

copper carb<strong>on</strong>ate, but may also c<strong>on</strong>tain copper sulfates <strong>and</strong> chlorides. However, rust is loose<br />

<strong>and</strong> e<strong>as</strong>ily removed, while verdigris forms a stable patina.<br />

More complex corrosi<strong>on</strong> patterns may occur e.g. "pitting corrosi<strong>on</strong>". This occurs following<br />

attack at discrete are<strong>as</strong> <strong>on</strong> the surface of the metal that are susceptible because of, for<br />

example, surface imperfecti<strong>on</strong>s or impurities in the metal. Pitting corrosi<strong>on</strong> is generally seen<br />

<strong>as</strong> small, local, are<strong>as</strong> of corrosi<strong>on</strong>. However, there may be c<strong>on</strong>siderably larger are<strong>as</strong> of<br />

corrosi<strong>on</strong> beneath the surface that can have significant effects <strong>on</strong> the strength of the affected<br />

metal.<br />

18

4.5.2. Corrosi<strong>on</strong> resistance<br />

Some <strong>metals</strong> (e.g. aluminium, chromium) are rendered "p<strong>as</strong>sive" (very resistant to corrosi<strong>on</strong>)<br />

by the sp<strong>on</strong>taneous formati<strong>on</strong>, in the presence of oxygen, of an invisible <strong>and</strong> impermeable<br />

oxide film a few Å thick. This p<strong>as</strong>sive layer is very str<strong>on</strong>g, very adherent <strong>and</strong> self-repairing if it<br />

is damaged.<br />

One of the main re<strong>as</strong><strong>on</strong>s for the producti<strong>on</strong> <strong>and</strong> use of metallic <strong>alloys</strong> is that <strong>alloys</strong> are<br />

virtually always more resistant to corrosi<strong>on</strong> than are their b<strong>as</strong>ic metal comp<strong>on</strong>ents.<br />

This is due, in part, to the fact that migrati<strong>on</strong> of the c<strong>on</strong>stituent elements is generally<br />

c<strong>on</strong>siderably lower than migrati<strong>on</strong> from n<strong>on</strong>-alloyed <strong>metals</strong> because of the micro-structural<br />

binding of the elements within the <strong>alloys</strong>. The relevant properties of <strong>alloys</strong> are described in more<br />

detail in the specific secti<strong>on</strong> <strong>on</strong> <strong>alloys</strong>, below.<br />

Stainless steels, which are <strong>alloys</strong> of ir<strong>on</strong> with a minimum of 10.5% chromium, are orders of<br />

magnitude more resistant to corrosi<strong>on</strong> than ir<strong>on</strong> itself. This is partly because they possess<br />

the general properties of <strong>alloys</strong>, referred to above, but mainly because they have a surface<br />

"p<strong>as</strong>sive film" which is naturally <strong>and</strong> rapidly formed <strong>on</strong> c<strong>on</strong>tact with the oxygen in air or water.<br />

Stainless steels <strong>used</strong> in <strong>food</strong> c<strong>on</strong>tact applicati<strong>on</strong>s are invariably <strong>used</strong> in the p<strong>as</strong>sive state. The<br />

corrosi<strong>on</strong> resistance of stainless steels is discussed in more detail in the specific secti<strong>on</strong> <strong>on</strong><br />

stainless steels.<br />

4.6. Abbreviati<strong>on</strong>s <strong>used</strong><br />

ADI<br />

FAO<br />

JECFA<br />

NOAEL<br />

PMTDI<br />

PTWI<br />

SCF<br />

TDI<br />

WHO<br />

Acceptable Daily Intake.<br />

Food <strong>and</strong> Agricultural Organizati<strong>on</strong> in UN.<br />

Joint FAO/WHO Expert Committee <strong>on</strong> Food Additives<br />

No Observed Adverse Effect Level.<br />

Provisi<strong>on</strong>ally Maximum Tolerable Daily Intake.<br />

Provisi<strong>on</strong>ally Tolerable Weekly Intake.<br />

Scientific Committee <strong>on</strong> Food of the European Uni<strong>on</strong>.<br />

Tolerable Daily Intake.<br />

World Health Organizati<strong>on</strong> in UN.<br />

4.7. References<br />

Directive 89/109/EEC: European Community. Council directive <strong>on</strong> the approximati<strong>on</strong> of the laws<br />

of the member states relating to <strong>materials</strong> <strong>and</strong> articles intended to come into c<strong>on</strong>tact with<br />

<strong>food</strong>stuffs. L40, p. 38.<br />

Directive 93/43/EEC: Council directive <strong>on</strong> the hygiene of <strong>food</strong>stuffs. L 175 p. 1-11.<br />

Directive 97/48/EEC: European community. Council directive <strong>on</strong> c<strong>on</strong>trol of migrati<strong>on</strong> from pl<strong>as</strong>tic<br />

articles. L 222 p. 10.<br />

EN ISO 8442-1. European St<strong>and</strong>ard. Materials <strong>and</strong> articles in c<strong>on</strong>tact with <strong>food</strong>stuffs - cutlery<br />

<strong>and</strong> table hollow-ware - Part 1: Requirements for cutlery for the preparati<strong>on</strong> of <strong>food</strong> (ISO/DIS<br />

8442-1:1997). Final draft, May 1997.<br />

19

Florence, T.M., Batley, G.E. (1980). Chemical speciati<strong>on</strong> in natural waters. CRC Critical<br />

Reviews in Analytical chemistry. p. 219-296.<br />

Vouk, V. (1986). General chemistry of <strong>metals</strong>. In: Friberg, L., Nordberg, G.F., Vouk, V.B.:<br />

H<strong>and</strong>book <strong>on</strong> the toxicology of <strong>metals</strong>. Sec<strong>on</strong>d editi<strong>on</strong>. Elsevier, Amsterdam, New York, Oxford.<br />

20

SPECIFIC GUIDELINES<br />

21

Guideline for aluminium<br />

Introducti<strong>on</strong><br />

Aluminium is the third most abundant element in the earth crust <strong>and</strong> is found widespread in<br />

minerals (Codex, 1995). Aluminium does not occur in nature in a free element state because of<br />

its reactive nature (Beliles, 1994). Many of its natural-occurring compounds are insoluble at<br />

neutral pH <strong>and</strong> thus c<strong>on</strong>centrati<strong>on</strong>s of the element in water, both fresh <strong>and</strong> sea-water are<br />

usually low, less than 0.1 mg/l. Inorganic compounds of aluminium normally c<strong>on</strong>tain Al(III). Pure<br />

aluminium h<strong>as</strong> good working <strong>and</strong> forming properties <strong>and</strong> high ductility, its mechanical strength<br />

being low. Therefore, aluminium is often <strong>used</strong> in <strong>alloys</strong> (Beliles, 1994).<br />

Main sources of aluminium in the diet<br />

The main source of aluminium is the natural occurring c<strong>on</strong>tent in <strong>food</strong>stuff. Unprocessed<br />

<strong>food</strong>stuff can c<strong>on</strong>tain between about 0.1 to 20 mg/kg of aluminium. The me<strong>as</strong>ured levels of<br />

aluminium in unprocessed <strong>food</strong>stuffs range from less than 0.1 mg/kg in eggs, apples, raw<br />

cabbage, corn, <strong>and</strong> cucumbers (ATSDR, 1997) to 4.5 mg/kg in tea (Penningt<strong>on</strong> <strong>and</strong> J<strong>on</strong>es,<br />

1989; Penningt<strong>on</strong> <strong>and</strong> Schoen, 1995; MAFF, 1993); much higher values are found in some<br />

industrially processed <strong>food</strong> with aluminium salts added <strong>as</strong> <strong>food</strong> additives. However, in the EU<br />

the use of aluminium salts <strong>as</strong> <strong>food</strong> additives is limited to certain products like sc<strong>on</strong>es <strong>and</strong><br />

aluminium itself is accepted for decorati<strong>on</strong> of c<strong>on</strong>fecti<strong>on</strong>ary (Directive 95/2/EC). Aluminium is<br />

also <strong>used</strong> in medical therapy in amounts up to 5 g/pers<strong>on</strong>/day (Codex, 1995; Elinder & Sjögren,<br />

1986; Li<strong>on</strong>e, 1985).<br />

Metallic <strong>food</strong> c<strong>on</strong>tact <strong>materials</strong><br />

Aluminium is widely <strong>used</strong> in <strong>food</strong> c<strong>on</strong>tact <strong>materials</strong> such <strong>as</strong> saucepans, aluminium-lined cooking<br />

utensils, coffee pots, <strong>and</strong> in packaging products such <strong>as</strong> <strong>food</strong>-trays, cans, can ends <strong>and</strong><br />

closures (Elinder <strong>and</strong> Sjögren, 1986; Codex, 1995). Aluminium <strong>food</strong> c<strong>on</strong>tact <strong>materials</strong> are often<br />

coated with a resin b<strong>as</strong>ed coating. Aluminium <strong>alloys</strong> for <strong>food</strong> c<strong>on</strong>tact <strong>materials</strong> may c<strong>on</strong>tain<br />

alloying elements such <strong>as</strong> magnesium, silic<strong>on</strong>e, ir<strong>on</strong>, manganese, copper <strong>and</strong> zinc (European<br />

St<strong>and</strong>ard EN 601; European St<strong>and</strong>ard EN 602).<br />

Other <strong>food</strong> c<strong>on</strong>tact <strong>materials</strong><br />

Certain aluminium compounds are <strong>used</strong> in pigments (Elinder <strong>and</strong> Sjögren, 1986).<br />

Migrati<strong>on</strong> informati<strong>on</strong><br />

Aluminium <strong>and</strong> its various <strong>alloys</strong> are highly resistant to corrosi<strong>on</strong> (Beliles, 1994). When<br />

exposed to air, the metal develops a thin film of AL 2 O 3 almost immediately. The reacti<strong>on</strong> then<br />

slows because the film seals off oxygen, preventing further oxidati<strong>on</strong> or chemical reacti<strong>on</strong>. The<br />

film is colourless, tough <strong>and</strong> n<strong>on</strong>flaking. Few chemicals can dissolve it (Beliles, 1994).<br />

23

Aluminium reacts with acids. Pure aluminium is attacked by most dilute mineral acids. At<br />

neutral pH, aluminium hydroxide h<strong>as</strong> limited solubility. However, the solubility incre<strong>as</strong>es<br />

markedly at pH below 4.5 <strong>and</strong> above 8.5 (Elinder <strong>and</strong> Sjögren, 1986). Alkalis attack both pure<br />

<strong>and</strong> impure aluminium rapidly <strong>and</strong> dissolve the metal (Hughes, 1992). Therefore, aluminium<br />

can migrate from uncoated surfaces in c<strong>on</strong>tact with <strong>food</strong>stuff. Aluminium migrati<strong>on</strong> from coated<br />

aluminium surface is insignificant. Uptake of aluminium from uncoated <strong>food</strong> c<strong>on</strong>tact <strong>materials</strong><br />

depends to a large extent <strong>on</strong> the acidity of the <strong>food</strong>stuffs. High salt c<strong>on</strong>centrati<strong>on</strong>s (over 3.5%<br />

NaCl) can also incre<strong>as</strong>e the migrati<strong>on</strong>. Use of uncoated aluminium saucepans, aluminium-lined<br />

cooking utensils <strong>and</strong> c<strong>on</strong>tainers may incre<strong>as</strong>e the c<strong>on</strong>tent of aluminium in certain types of<br />

<strong>food</strong>stuffs, especially during l<strong>on</strong>g-term storage of str<strong>on</strong>gly acidic or salty, liquid <strong>food</strong>stuff. In<br />

general, cooking in aluminium vessels incre<strong>as</strong>es the c<strong>on</strong>tent in the <strong>food</strong>stuffs less than 1 mg/kg<br />

for about half the <strong>food</strong>stuffs examined, <strong>and</strong> less than 10 mg/kg for 85% of the <strong>food</strong>stuffs<br />

examined (Penningt<strong>on</strong> <strong>and</strong> J<strong>on</strong>es, 1989). Boiling of tap water in an aluminium pan for 10 or 15<br />

minutes can result in aluminium migrati<strong>on</strong> of up to 1,5 mg/l, depending <strong>on</strong> the acidity of the<br />

water <strong>and</strong> the chemical compositi<strong>on</strong> of the aluminium utensils (Gramicci<strong>on</strong>i et al., 1996; Müller<br />

et al., 1993; Mei et al., 1993; Nagy et al, 1994) but values up to 5 mg/l have been reported in<br />

<strong>on</strong>e study (Liukk<strong>on</strong>en-Lilja <strong>and</strong> Piepp<strong>on</strong>en, 1992).The <strong>food</strong>stuffs which most frequently take up<br />

more aluminium from the c<strong>on</strong>tainers are acidic <strong>food</strong>stuffs such <strong>as</strong> tomatoes, cabbage, rhubarb<br />

<strong>and</strong> many soft fruits (Hughes, 1992). Whilst acids give the highest figures, alkaline <strong>food</strong>stuffs<br />

(less comm<strong>on</strong>) <strong>and</strong> <strong>food</strong>stuffs with much added salt, do incre<strong>as</strong>e the aluminium uptake<br />

(Hughes, 1992; Gramicci<strong>on</strong>i et al., 1996). In aluminium cans the producti<strong>on</strong> of hydrogen g<strong>as</strong><br />

from aluminium migrati<strong>on</strong> produces an over pressure in the can.<br />

The temperature <strong>and</strong> storage time is known to influence the migrati<strong>on</strong> of aluminium into<br />

<strong>food</strong>stuff. In a migrati<strong>on</strong> study with 3% acetic acid (Gramicci<strong>on</strong>i et al., 1989), the migrati<strong>on</strong> w<strong>as</strong><br />

approximately 10 fold higher at 40°C compared to 5°C after 24 hours (for general remarks <strong>on</strong><br />

migrati<strong>on</strong> testing – see the introducti<strong>on</strong>). Typical values for migrati<strong>on</strong> of aluminium from foil w<strong>as</strong><br />

C<strong>on</strong>clusi<strong>on</strong>s <strong>and</strong> recommendati<strong>on</strong>s<br />

Storage of str<strong>on</strong>gly acidic (e.g. fruit juices) or str<strong>on</strong>gly salty, liquid <strong>food</strong>stuffs in uncoated<br />

aluminium utensils should be limited in order to minimise migrati<strong>on</strong>.<br />

Labelling for users of uncoated aluminium should be given by the producer. The labelling,<br />

where appropriate could be: “User informati<strong>on</strong>. Do not use this utensil to store acidic or salty<br />

humid <strong>food</strong> before or after cooking” or “To be <strong>used</strong> for storing <strong>food</strong> in refrigerator <strong>on</strong>ly”.<br />

Guidance should be available from producers of uncoated aluminium utensils regarding the<br />

use of their product with str<strong>on</strong>gly acidic or salty <strong>food</strong>stuff.<br />

Manufactures should comply with the GMP for aluminium alloy semi products intended to<br />

come into c<strong>on</strong>tact with <strong>food</strong>stuff.<br />

References<br />

1. ATSDR (1997). Toxicological profile for aluminium. Draft for public comment. U.S.<br />

Department of Health <strong>and</strong> Human Services. Public Health Service. Agency for Toxic<br />

Substances <strong>and</strong> Dise<strong>as</strong>e Registry.<br />

2. Beliles, R.P. (1994). The <strong>metals</strong>. In: Patty’s Industrial Hygiene <strong>and</strong> Toxicology, Fourth<br />

editi<strong>on</strong>, Volume 2, Part C. Edited by Clayt<strong>on</strong>, G.D., <strong>and</strong> Clayt<strong>on</strong>, F.E. John Wiley & S<strong>on</strong>s,<br />

Inc.<br />

3. Codex Alimentarius Commissi<strong>on</strong> (1995). Doc. no. CX/FAC 96/17. Joint FAO/WHO <strong>food</strong><br />

st<strong>and</strong>ards programme. Codex general st<strong>and</strong>ard for c<strong>on</strong>taminants <strong>and</strong> toxins in <strong>food</strong>s.<br />

4. Directive 95/2/EC: European Community. European Parliament <strong>and</strong> Council Directive <strong>on</strong><br />

<strong>food</strong> additives other than colours <strong>and</strong> sweeteners.<br />

5. Directive 98/83/EC: Council Directive 98/83/EC of 3 November 1998 <strong>on</strong> the quality of<br />

water intended for human c<strong>on</strong>sumpti<strong>on</strong>.<br />

6. Elinder <strong>and</strong> Sjögren (1986). Aluminium. In: Friberg, L., Nordberg, G.F., Vouk, V.B.:<br />

H<strong>and</strong>book <strong>on</strong> the toxicology of <strong>metals</strong>. Sec<strong>on</strong>d editi<strong>on</strong>. Elsevier, Amsterdam, New York,<br />

Oxford.<br />

7. European St<strong>and</strong>ard CEN EN 601. Aluminium <strong>and</strong> aluminium <strong>alloys</strong> - C<strong>as</strong>tings - Chemical<br />

compositi<strong>on</strong> of c<strong>as</strong>tings for use in c<strong>on</strong>tact with <strong>food</strong>.<br />

8. European St<strong>and</strong>ard CEN EN 602. Aluminium <strong>and</strong> aluminium <strong>alloys</strong> - Wrought products -<br />

Chemical compositi<strong>on</strong> of semi products <strong>used</strong> for the fabricati<strong>on</strong> of articles for use in c<strong>on</strong>tact<br />

with <strong>food</strong>.<br />

9. Gramicci<strong>on</strong>i, L. et al. (1989). An experimental study about aluminium packaged <strong>food</strong>. In:<br />

“Nutriti<strong>on</strong>al <strong>and</strong> Toxicological <strong>as</strong>pects of <strong>food</strong> processing”. Proceedings of an internati<strong>on</strong>al<br />

symposium, Rome, April 14-16, 1987. Walker, R. <strong>and</strong> Quattrucci Eds. Taylor & Francis<br />

L<strong>on</strong>d<strong>on</strong>, p. 331-336.<br />

10.Gramicci<strong>on</strong>i, L., Ingrao, G., Milana, M.R., Santar<strong>on</strong>i, P., Tom<strong>as</strong>si, G. (1996). Aluminium<br />

levels in Italian diets <strong>and</strong> in selected <strong>food</strong>s from aluminium utensils. Food Additives <strong>and</strong><br />

C<strong>on</strong>taminants. Vol. 13(7) p. 767-774.<br />

11.Hughes, J.T. (1992). Aluminium <strong>and</strong> your health. British Library Cataloguing in Publicati<strong>on</strong><br />

Data, Rimes House.<br />

12.IPCS (1997). IPCS report no. 194: Envir<strong>on</strong>mental Health Criteria - aluminium. World Health<br />

Organizati<strong>on</strong>.<br />

13.JECFA (1989). Evaluati<strong>on</strong> of certain <strong>food</strong> additives <strong>and</strong> c<strong>on</strong>taminants. Thirty-third report of<br />

the Joint FAO/WHO Expert Committee <strong>on</strong> Food Additives. World Health Organizati<strong>on</strong>,<br />

Technical Report Series 776.<br />

25

14.Li<strong>on</strong>e, A. (1985). Aluminium toxicology <strong>and</strong> the aluminium-c<strong>on</strong>taining medicati<strong>on</strong>.<br />

Pharmacol. Ther. Vol. 29 p. 225-285.<br />

15.Liukk<strong>on</strong>en-Lilja, H. <strong>and</strong> Piepp<strong>on</strong>en (1992). Leaching of aluminium from aluminium dishes<br />

<strong>and</strong> packages. Food Additives <strong>and</strong> C<strong>on</strong>taminants, vol 9(3) p. 213-223.<br />

16.MAFF (1998). Lead arsenic <strong>and</strong> other <strong>metals</strong> in <strong>food</strong>. Food surveillance paper no. 52. The<br />

Stati<strong>on</strong>ery Office, L<strong>on</strong>d<strong>on</strong>. ISBN 0 11 243041 4.<br />

17.Mei, L., Yao, T. (1993). Aluminium c<strong>on</strong>taminati<strong>on</strong> of <strong>food</strong> from using aluminium ware. Intern.<br />

J. Envir<strong>on</strong>. Anal. Chem. Vol. 50 p. 1-8.<br />

18.Müller, J.P., Steinegger, A., Schlatter, C. (1993). C<strong>on</strong>tributi<strong>on</strong> of aluminium from packaging<br />

<strong>materials</strong> <strong>and</strong> cooking utensils to the daily aluminium intake. Z. Lebensm. Unters. Forsch.<br />

Vol. 197 p. 332-341.<br />

19.Nagy, E., Jobst, K. (1994). Aluminium dissolved from kitchen utensils. Bull. Envir<strong>on</strong>. C<strong>on</strong>tam.<br />

Toxicol. Vol. 52 9. 396-399.<br />

20.Penningt<strong>on</strong>, J.A.T., J<strong>on</strong>es, J.W. (1989). Dietary intake of aluminium. Aluminium <strong>and</strong> Health –<br />

A critical review. Gitelman, p. 67-70.<br />

21.Penningt<strong>on</strong>, J.A.T., Schoen, S.A. (1995). Estimates of dietary exposure to aluminium. Food<br />

additives <strong>and</strong> c<strong>on</strong>taminants, vol. 12 no. 1, p. 119-128.<br />

22.WHO (1993). <str<strong>on</strong>g>Guidelines</str<strong>on</strong>g> for drinking-water quality. volume 1, Recommendati<strong>on</strong>s.<br />

26

Guideline for chromium<br />

Introducti<strong>on</strong><br />

Chromium is found in the envir<strong>on</strong>ment mainly in the trivalent form. Hexavalent chromium, or<br />

chromate, may also be found in very small amounts, arising usually from anthropogenic<br />

sources (Beliles, 1994). Cr(III) h<strong>as</strong> the ability to form str<strong>on</strong>g, inert complexes with a wide range<br />

of naturally occurring organic <strong>and</strong> inorganic lig<strong>and</strong>s (Florence <strong>and</strong> Batley, 1980). In most soils<br />

<strong>and</strong> bedrocks, chromium is immobilised in the trivalent state (Florence <strong>and</strong> Batley, 1980).<br />

Chromium is an essential element to man. Chromium is found at low levels in most biological<br />

<strong>materials</strong>.<br />

Main sources of chromium in the diet<br />

The main sources of chromium are cereals, meat, vegetables <strong>and</strong> unrefined sugar, while fish,<br />

vegetable oil <strong>and</strong> fruits c<strong>on</strong>tain smaller amounts (Codex, 1995). Most <strong>food</strong>stuffs c<strong>on</strong>tain less<br />

than 0.1 mg chromium per kg (Nordic Council of Ministers, 1995). Chromium is present in the<br />

diet mainly <strong>as</strong> Cr(III) (Codex, 1995). As with all <strong>metals</strong>, <strong>food</strong> c<strong>on</strong>taminati<strong>on</strong> may be ca<strong>used</strong> by<br />

atmospheric fall-out (Codex, 1995).<br />

Metallic <strong>food</strong> c<strong>on</strong>tact <strong>materials</strong><br />

Chromium is found in some types of cans <strong>and</strong> utensils. In cans it serves to p<strong>as</strong>sivate the tinplate<br />

surface. Chromium is <strong>used</strong> in the producti<strong>on</strong> of stainless steel of various kinds <strong>and</strong> in <strong>alloys</strong> with<br />

ir<strong>on</strong>, nickel <strong>and</strong> cobalt. Ferro chromium <strong>and</strong> chromium metal are the most important cl<strong>as</strong>ses of<br />

chromium <strong>used</strong> in the alloy industry (Langaard <strong>and</strong> Norseth, 1986). Chromium c<strong>on</strong>taining<br />

stainless steels (see guideline <strong>on</strong> stainless steel) are important <strong>food</strong> c<strong>on</strong>tact <strong>materials</strong> <strong>used</strong> for<br />

transportati<strong>on</strong>, e.g. in milk trucks, for processing equipment, e.g. in the dairy <strong>and</strong> chocolate<br />

industry, in processing of fruit such <strong>as</strong> apples, grapes, oranges <strong>and</strong> tomatoes, for c<strong>on</strong>tainers<br />

such <strong>as</strong> wine tanks, for brew kettles <strong>and</strong> beer kegs, for processing of dry <strong>food</strong> such <strong>as</strong> cereals,<br />

flour <strong>and</strong> sugar, for utensils such <strong>as</strong> blenders <strong>and</strong> bread dough mixers, in slaughter-houses, in<br />

processing of fish, for nearly all of the equipment in big kitchens, such <strong>as</strong> restaurants, hospitals,<br />

electric kettles, cookware <strong>and</strong> kitchen appliances of any kind such <strong>as</strong> sinks <strong>and</strong> drains, for<br />

bowls, knives, spo<strong>on</strong>s <strong>and</strong> forks. Chromium is also <strong>used</strong> to coat other <strong>metals</strong>, which are then<br />

protected from corrosi<strong>on</strong> because of the p<strong>as</strong>sive film which forms <strong>on</strong> the surface of chromium.<br />

Other <strong>food</strong> c<strong>on</strong>tact <strong>materials</strong><br />

Chromium compounds are found in pottery, glazes, paper <strong>and</strong> dyes (Langaard <strong>and</strong> Norseth,<br />

1986).<br />

Migrati<strong>on</strong> informati<strong>on</strong><br />

Canned <strong>food</strong>stuffs in n<strong>on</strong>-lacquered cans <strong>and</strong> other processed <strong>food</strong>stuffs, particularly acidic<br />

<strong>food</strong>stuffs such <strong>as</strong> fruit juices, may be significantly higher in chromium than fresh <strong>food</strong>stuffs. A<br />

small c<strong>on</strong>tributi<strong>on</strong> to chromium intake can be made by uptake from cans. However, the<br />

significance of this is probably negligible. Chromium from <strong>materials</strong> <strong>and</strong> articles is expected to<br />

migrate <strong>as</strong> Cr(III) <strong>and</strong> not <strong>as</strong> Cr(VI) (Guglhofer <strong>and</strong> Bianchi, 1991). Cr(III) can not migrate at<br />

neutral pH in <strong>food</strong>stuffs. Therefore, the migrati<strong>on</strong> of Cr(III) to <strong>food</strong>s of pH 5 or above is low.<br />