Download as PDF - Daylight & Architecture - Magazine by | VELUX

Download as PDF - Daylight & Architecture - Magazine by | VELUX

Download as PDF - Daylight & Architecture - Magazine by | VELUX

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

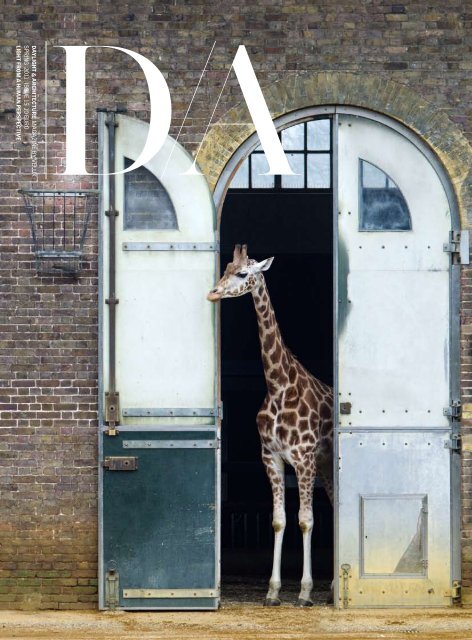

DAYLIGHT & ARCHITECTURE MAGAZINE BY <strong>VELUX</strong>SPRING 2011 Issue 15 10 EuroLIGHT FROM A HUMAN PERSPECTIVE

<strong>VELUX</strong>EDITORIAL<strong>Daylight</strong> ina humanperspectiveFor more than a century, architects andlighting consultants have optimised the useof daylight in buildings to support humanvision. The positive effects of natural lighton human health and well-being have alsobeen acknowledged but rarely incorporatedinto building codes and everyday designpractice.During the l<strong>as</strong>t decade, however,researchers have gained insight into previouslyundiscovered benefits of daylight thatcall for a new approach to building design:natural light is essential to human circadianregulation. A lack of daylight can severelydisturb our time rhythms, causing healthproblems such <strong>as</strong> sleep disturbance, stressand obesity.In modern society, we spend up to 90%of our time indoors, and much research suggeststhat our daily light dose is too smallto keep us healthy. So sufficient provisionof daylight is crucial in every building – notonly for re<strong>as</strong>ons of energy efficiency but forthe sake of our own well-being. This insightis, however, not yet widely shared with consultantsand the building industry. There areno proper guidelines for daylight and health,even though considerable research anddocumentation seems to exist on how theintensity, time, duration, spectrum and distributionof exposure to light affects humanbehaviour and physiology.This issue of D/A explores which conditions,or combination of conditions, will promotehuman health and well-being indoors.It also raises the question of how the necessarybridges between daylight research andarchitectural design can be built, thus makinga real difference to future buildings.We present perspectives from four leadingresearchers and thinkers: circadian neuroscientistRussell Foster, environmentalpsychologist Judith Heerwagen and thearchitects Dean Hawkes and Brent Richardsapproach daylight from a human perspective.This edition also portrays four architectoffices from different parts of the world:SANAA from Japan, Will Bruder from theUSA, Jarmund/Vigsnaes from Norway, andLacaton & V<strong>as</strong>sal from France. Their buildingsare <strong>as</strong> diverse <strong>as</strong> the cultures and climatesfor which they were designed, butat the same time, they cater for universalhuman needs; to be protected from a harshclimate at the same time <strong>as</strong> being in closecontact with nature. A selected projectfrom each office is documented for the daylithours of one day.The winners of the International <strong>VELUX</strong>Award for Students of <strong>Architecture</strong> 2010took up the challenge to portray “The lightin my room” over the daylit hours of one day.In their photo project, they considered thedifferent qualities of light <strong>as</strong> well <strong>as</strong> manyquestions about the nature of light: How dowe perceive light through our senses? Andhow does the camera capture light?The <strong>VELUX</strong> Group strongly believes inthe beneficial effects of daylight. We believethat we need more stringent requirementsin building codes – and that operationalmethods and performance indicators needto be developed alongside useful guidelinesand tools for the professionals. The fourth<strong>VELUX</strong> <strong>Daylight</strong> Symposium in the RolexLearning Centre in May 2011 will focus specificallyon the effects of daylight on buildingoccupants, how we are affected <strong>by</strong> daylightand what the requirements are to achievegood daylit environments. We believe thatbuilding design should consider all dimensionsof people’s needs – and that they shouldbe b<strong>as</strong>ed on insight that is shared betweenresearchers and practising architects andengineers.Enjoy the read!1

SPRING 20116 14 244254 56ISSUE 15ContentsBody Clocks, Light,Sleep and HealthThe experienceof daylightImagining light: theme<strong>as</strong>ureable andthe unme<strong>as</strong>urableof daylight designIn search of ananthropologyof daylight4×ARCHITECTURE &DAYLIGHTWILL BRUDER:“Light definesthe journey ofour lives”<strong>VELUX</strong> Editorial 2Contents 4Body Clocks, Light, Sleep and Health 6The experience of daylight 14Imagining Light: The me<strong>as</strong>ureable and the 24unme<strong>as</strong>urable of daylight designIn search of an anthropology of daylight 424×<strong>Architecture</strong> & <strong>Daylight</strong> 54Will Bruder: “Light defines the journey of my life” 56Sanaa: A spatial invitation to presence 70Jarmund Wigsnaes: “We need to rediscover the economy of daylight” 82Lacaton/V<strong>as</strong>sal: ”Light is freedom” 94IVA, International Velux Award 104The everyday poetics of life 106“We live our lives in dim caves,” saysthe neurophysiologist Russell Foster.Electric light and the emergenceof the ‘round-the-clock’ society haveincre<strong>as</strong>ingly isolated us from therhythms of nature. In his article for<strong>Daylight</strong> & <strong>Architecture</strong>, Foster describesthe consequences this is havingfor human beings.Why do people prefer daylight toartificial light, even though bothprovide enough light to see <strong>by</strong>? Environmentalpsychologist JudithHeerwagen investigated this matterclosely and, referring to current research,came to the conclusion thatthis preference is due to human evolution.“A room is not a room without naturallight,” says the American architectLouis Kahn. In his article,Dean Hawkes examines how Kahnand other pioneering architectshave worked with daylight in theirbuildings. Great architecture, accordingto Hawkes, is b<strong>as</strong>ed on theoptimal relationship of quantitativeand qualitative <strong>as</strong>pects in the use ofdaylight.Many architects value the functionaland aesthetic advantagesof daylight but only know very littleabout its psychological effect. Inhis article, Brent Richards looks athow these are<strong>as</strong> of knowledge canbe more closely interlinked. His conclusion:two things are necessary –the holistically thinking architect,and interdisciplinary planning teamsin which specialists in different subjectsinspire each other.Every building h<strong>as</strong> to mediate anewbetween a specific site with its climateand daylight, and universalhuman needs. How this can be donesuccessfully is shown in <strong>Daylight</strong> &<strong>Architecture</strong> <strong>by</strong> four architects’ officesfrom all over the world: WillBruder from Phoenix, SANAA fromTokyo, Jarmund/Vigsnæs from Osloand Lacaton & V<strong>as</strong>sal from Paris.The American architect Will Bruderh<strong>as</strong> been living in Phoenix, Arizona,for more than 40 years. The city,the surrounding desert landscapeand its light have exerted a l<strong>as</strong>tinginfluence on his work. In an interviewwith <strong>Daylight</strong> & <strong>Architecture</strong>,Bruder describes how he makes useof light to ennoble even the mostsimple structures and materials inhis buildings.6 14 24 502 D&A SPRING 2011 Issue 15 3

70 82 94 10894SANAA:A spatialinvitation topresenceJARMUND/VIGSNæS:“We need torediscover theeconomy ofdaylight”LACATON&VASSAL:“Light is freedom”The everydaypoetics of lightThe buildings of SANAA are a productof Japanese culture and its ownvery special relationship to daylight,nature and technology. Per Olaf Fjeldh<strong>as</strong> examined the architecture of thePritzker prize winners for <strong>Daylight</strong> &<strong>Architecture</strong>. SANAA, he writes, notonly uses daylight to create visual effectsbut also uses it <strong>as</strong> a means ofshaping spaces.The work of the Norwegian architectsJarmund/Vigsnæs is firmlyrooted in the Norwegian culture andlandscape. In an environment that isdetermined <strong>by</strong> stark contr<strong>as</strong>ts, theirbuildings seek to establish a balancebetween sheltering and opening up,between opaqueness and transparency,and between different qualitiesof daylight and views.Freedom, openness and economy ofmeans are key concepts in the workof Lacaton & V<strong>as</strong>sal. In an interview,the Parisian architects, who wonthe <strong>Daylight</strong> & Building ComponentAward of the <strong>VELUX</strong> Foundation in2011, explain why they hardly evererect walls in their buildings – andwhat contemporary architects canlearn from Africa.We decide for ourselves how we live–but daylight also plays an importantrole in the decision. In order toget to the bottom of this phenomenon,the winners and runners-upof the International <strong>VELUX</strong> Award2010 made a photographic recordof the daylight in their homes over aperiod of a day.70824 D&A SPRING 2011 Issue 15 5

Body Clocks,Light, Sleepand HealthThe eye establishes a connectionto the outer world not onlyfor our sense of sight but also forour sense of time and for manytemporal processes in our body.Over the l<strong>as</strong>t one and a half centuries, artificial light and the restructuringof working times have seemingly ‘liberated’ us from the diurnal cyclesof light and dark that nature imparts on us. Yet recent research h<strong>as</strong>shown that this separation from nature comes at a considerable cost,causing health and social problems. A reconnection to the rhythms ofnature is therefore needed – and this will also have a profound influenceon architecture.By Russell G. FosterIllustrations <strong>by</strong> Ulrika Nilsson CarlssonOur lives are ruled <strong>by</strong> time and we usetime to tell us what to do. But the digitalalarm clock that wakes us in the morningor the wrist-watch that tells us we are latefor supper are unnatural clocks. Our biologyanswers to a profoundly more ancientbeat that probably started to tick early inthe evolution of all life. Embedded withinour genes, and almost all life on earth, arethe instructions for a biological clock thatmarks the p<strong>as</strong>sage of approximately 24hours. Biological clocks or ‘circadianclocks’ (circa about, diem a day) helptime our sleep patterns, alertness, mood,physical strength, blood pressure andmuch more. Under normal conditions weexperience a 24-hour pattern of light anddark, and our circadian clock uses this signalto align biological time to the day andnight. The clock is then used to anticipatethe differing demands of the 24-hour dayand fine-tune physiology and behaviourin advance of the changing conditions.Body temperature drops, blood pressuredecre<strong>as</strong>es, cognitive performance dropsand tiredness incre<strong>as</strong>es in anticipationof going to bed. Whilst before dawn, metabolismis geared-up in anticipation ofincre<strong>as</strong>ed activity when we wake.Few of us appreciate this internal world,seduced <strong>by</strong> an apparent freedom to sleep,work, eat, drink, or travel when we want.But this freedom is an illusion; in realitywe are not free to act independently of thebiological order that the circadian clockimparts. We are unable to perform withthe same efficiency throughout the 24hday. Life h<strong>as</strong> evolved on a planet that experiencesprofound changes in light overthe 24h day and our biology anticipatesthese changes and needs to be exposedto the natural pattern of light and darkto function properly. Yet we detach ourselvesfrom the environment <strong>by</strong> forcingour nights into days using electric light,and isolate ourselves in buildings thatshield us from natural light. This shortreview considers some of the importantconsequences of our incre<strong>as</strong>ing detachmentfrom the sun.The day withinAt the b<strong>as</strong>e of the brain, in a structureknown <strong>as</strong> the anterior hypothalamus, isa cluster of about 50,000 neurones known<strong>as</strong> the suprachi<strong>as</strong>matic nuclei or SCN. Ifthis region is destroyed <strong>as</strong> a result of <strong>as</strong>troke or tumour, then 24h rhythmicityis lost and physiology becomes randomlydistributed across the day. The findingthat individual SCN neurones, isolatedfrom all other cells, show near 24-hourrhythms in electrical activity demonstratedthat the b<strong>as</strong>ic mechanisms thatgenerate this internal day must be partof a sub-cellular molecular mechanism.To date, approximately 14-20 genes andtheir protein products have been linkedto the generation of circadian rhythms.At the heart of the molecular clock is anegative feedback loop that consists of thefollowing sequence of events: the clockgenes are transcribed and the messengerRNAs (mRNAs) move to the cytopl<strong>as</strong>m ofthe cell and are translated into proteins;The proteins interact to form complexesand then move from the cytopl<strong>as</strong>m intothe nucleus and inhibit the transcriptionof their own genes; the inhibitory clockprotein complexes are then degradedand the core clock genes are once morefree to make their mRNA and hence freshprotein. This negative feedback loop generatesa near 24-hour rhythm of proteinproduction and degradation that encodesthe biological day.The original <strong>as</strong>sumption w<strong>as</strong> that SCNneurones collectively drive or impose a24h rhythm on physiology and behaviour.However, the discovery that isolated cellsfrom almost any organ of the body produceclock genes/proteins in a circadianpattern led to a major shift in our understanding.We now appreciate that the SCNacts <strong>as</strong> a m<strong>as</strong>ter pacemaker, coordinatingthe activity of all cellular clocks in a mannerthat h<strong>as</strong> been likened to the conductorof an orchestra, regulating the timing ofthe multiple and varied components ofthe ensemble. In the absence of the SCN,the individual cellular clocks of the organsystems drift apart and coordinated circadianrhythms collapse – a state known <strong>as</strong>internal desynchronisation. Internal desynchronisationis the main re<strong>as</strong>on whywe feel so awful <strong>as</strong> a result of jet lag. All thedifferent organ systems, the brain, liver,gut, muscles etc., are working at a slightlydifferent time. Only when internal timeh<strong>as</strong> been re-aligned can we function normallyonce more.7

Inner timepiece: special photoreceptorsin the ganglion cellsof the optic nerve synchroniseour inner clock with the cyclesof light and dark in our environment– and thus with local time.Our body clocks are different –genes and hormones?Our body clocks are not all the same. Ifyou are alert in the mornings and go tobed early you are a ‘lark’, but if you hatemornings and want to keep going throughthe night, then you are an ’owl’.These terms have been used to describethe real phenomenon of diurnalpreference – the times when you preferto sleep and when you do your best work.Diurnal preference is determined partly<strong>by</strong> our clock genes. Exciting researchin recent years h<strong>as</strong> shown that smallchanges in these genes have been linkedto the f<strong>as</strong>t clocks (shorter than 24h) oflarks or slower clocks (longer than 24h)of owls. But it is not just our genes thatregulate our diurnal preference. Sleeptiming changes markedly <strong>as</strong> we age. Bythe time of puberty, bed times and waketimes drift to later and later hours. Thistendency to get up later continues untilabout the age of 19.5 years in womenand 21 years in men. At this point thereis a reversal and a drift towards earliersleep and wake times. By the age of55–60 we are getting up <strong>as</strong> early <strong>as</strong> wedid when we were 10. These and alliedresults demonstrate that young adultsreally do have a problem getting upin the morning. Teenagers show bothdelayed sleep and high levels of sleepdeprivation, because they are going tobed late but still having to get up earlyin the morning to go to school. Thesereal biological effects have been largelyignored in terms of the time structureimposed upon teenagers at school. Ofthe few studies undertaken, later startingtimes for schools have been shown toimprove alertness and the mental abilitiesof students during their morning lessons.Ironically, whilst young adults tendto improve their performance across theday, their older teachers show a decline inperformance over the same period! Themechanisms for this change in diurnalpreference remain poorly understood,but are thought to relate to the markedchanges in our steroid hormones (e.g.testosterone, oestrogen, progesterone)and their rapid rise during puberty andsubsequent slower decline.Light clocks and alertnessA clock is not a clock unless it can be setto local time – and the molecular clockswithin the SCN are normally adjusted(entrained) <strong>by</strong> daily exposure to lightaround dawn and dusk detected <strong>by</strong> theeyes. Failure to expose the clock to a stablelight/dark cycle results in drifting or‘free-running’ circadian rhythms or disruptedcycles. Detachment from solarday is common in industrialised societiesand the special c<strong>as</strong>e of shift workerswill be discussed below; however isolationfrom robust dawn and dusk signalsoccurs in many different instances. Forexample, paediatric and adult intensivecare units frequently utilise low andconstant light. In such an environmentcircadian rhythms would be expected todrift and become desynchronised. The result,<strong>as</strong> discussed below in the sub-section’Disrupting the clock’, will be a weakenedhealth status of the patient. Light doesmore than regulate the timing of circadianrhythms – it also h<strong>as</strong> a direct effecton alertness and performance. Brainimaging following light exposure showsincre<strong>as</strong>ed activity in many of the brainare<strong>as</strong> involved in alertness, cognitionand memory (thalamus, hippocampus,brainstem) and mood (amygdala). Furthermore,incre<strong>as</strong>ed light h<strong>as</strong> been shownto improve concentration, the ability toperform cognitive t<strong>as</strong>ks and to reducesleepiness. As a result, inappropriate lightexposure in a building will not only disruptsleep and circadian timing but alsolevels of alertness and performance. Wewill return to this topic below.Our understanding of how light regulatescircadian rhythms and alertnessh<strong>as</strong> been advanced dramatically overthe p<strong>as</strong>t few years with the discovery ofan entirely new photoreceptor system inthe eye. This novel photoreceptor is notlocated in the part of the eye containingthe rods (night vision) and cones (day vision)that are used to generate an imageof the world, but in the ganglion cells thatform the optic nerve. Most ganglion cellsform a functional connection betweenthe eye and the brain, but a small numberof specialised ganglion cells (1–3%) are directlylight-sensitive and project to those“Of the few studies undertaken,later starting times for schoolshave been shown to improvealertness and the mental abilitiesof students during their morninglessons. Ironically, whilst youngadults tend to improve theirperformance across the day, theirolder teachers show a decline inperformance over the sameperiod!”parts of the brain involved in the regulationof circadian rhythms, sleep, alertness,memory and mood. These photosensitiveretinal ganglion cells (pRGCs) containa light-sensitive pigment called Opn4,which is most sensitive in the blue partof the spectrum with a peak sensitivityat 480 nm – very similar to the ‘blue’ of aclear blue sky. This light-detection systemh<strong>as</strong> evolved to be anatomically and functionallyindependent of the visual system,and probably evolved before vision <strong>as</strong> themain way to detect light for entrainingdaily rhythms. Remarkably, the pRGCscan still detect light to shift the circadianclock or affect alertness even in animalsor people where the rods and cones usedfor vision are completely destroyed andwho are otherwise totally visually blind.This raises important implications forophthalmologists who are largely unawareof this new photoreceptor systemand its impact on human physiology.In view of the colour sensitivity ofOpn4, we would predict that blue lightshould be the most effective wavelength(colour) for shifting circadian rhythmsand alerting the arousal systems. In allstudies undertaken to-date, this h<strong>as</strong> beenshown to be the c<strong>as</strong>e. Blue light exposureat night is most effective at shifting thetiming of the circadian clock, reducingsleepiness, improving reaction timesand activating are<strong>as</strong> of the brain mediatingalertness and sleep. In addition to itsspectrum, light timing, duration, patternand history all interact to influence circadianrhythms and alertness. Light timingis particularly important. Light can either8 D&A SPRING 2011 Issue 159

Even the colour of the sky h<strong>as</strong>lefts its traces in our genes:the photoreceptors of our‘biological clock’ react moresensitively to blue light thanto any other colour.advance (go to bed earlier) or delay (go tobed later) the circadian system dependingon the timing of exposure. Under conditionsof solar light exposure, light arounddusk causes a delay of the clock, where<strong>as</strong>light exposure around dawn will advancethe clock. This delaying and advancingeffect of light keeps the SCN locked ontoto the solar day. Such differential effectsof light become vitally important whentrying to understand the impact of jet lag,shift work (see below), or building designon sleep/wake timing.The pRGCs are not <strong>as</strong> sensitive to light<strong>as</strong> the rods and cones, so that short lightexposure that is e<strong>as</strong>ily detected <strong>by</strong> thevisual system is not recognised <strong>by</strong> thepRGCs. However, dim light can have aneffect if it is delivered over long periodsof time. Thus relatively dim indoor roomlight from bedside lamps and computerscreens (less than 100 lux) can have me<strong>as</strong>ureableeffects on the clock and arousalsystems over several hours, and may exacerbatesleep disorders. Collectively, theseeffects of light – spectral composition,time of exposure and brightness – havewidespread clinical and occupational applicationsin not only treating sleep disordersand fatigue but in the architecture ofhospitals, schools, offices, retail space anddomestic buildings.Disrupting the clock –shift work and 24/7The introduction of electricity and artificiallight in the 19th century and the restructuringof work times have progressivelydetached us from the solar 24-hourcycles of light and dark. The consequenceh<strong>as</strong> been disruption of the circadian andsleep systems. Much h<strong>as</strong> been writtenabout the effects of this disruption, andin general terms the effects are clear(Table 1). Sleep and circadian rhythmdisruption results in performance deficitsthat include incre<strong>as</strong>ed errors, poorvigilance, poor memory, reduced mentaland physical reaction times and reducedmotivation. Sleep deprivation and disruptionare also <strong>as</strong>sociated with a rangeof metabolic abnormalities, includingthe glucose/insulin axis. For example,sleep disrupted individuals take longerto regulate blood-glucose levels and insulincan fall to levels seen in the earlystages of diabetes — abnormalities thatcan be reversed <strong>by</strong> normal sleep. Such resultshave suggested that long-term sleepand circadian rhythm disruption mightcontribute to chronic conditions such <strong>as</strong>diabetes, obesity and hypertension. Furthermore,obesity is strongly correlatedwith sleep apnoea and hence additionalsleep disturbance. Under these circumstancesa dangerous positive feedbackloop of obesity and sleep disturbance canoften result.Sleep loss and circadian rhythm disruptionare most obvious in night-shiftworkers. More than 20% of the populationof employment age work at le<strong>as</strong>tsome of the time outside the 07.00–19.00day.Josephine Arendt at the University ofSurrey makes the point: “Because of theirrapidly changing and conflicting lightdarkexposure and activity-rest behaviour,shift workers can have symptoms similarto those of jet lag. Although travellers normallyadapt to the new time zone, shiftworkersusually live out of ph<strong>as</strong>e with localtime cues”. Even after 20 years of nightshiftwork, individuals will not normallyshift their circadian rhythms in responseto the demands of working at night. Despitethe great variety and complexity of‘shift systems’, none have been able to alleviatefully the circadian problems <strong>as</strong>sociatedwith shift work. Metabolism, alongwith alertness and performance, are stillhigh during the day when the night-shiftworker is trying to sleep and low at nightwhen the individual is trying to work. Amisaligned physiology, along with poorsleep, in night-shift workers h<strong>as</strong> been <strong>as</strong>sociatedwith incre<strong>as</strong>ed cardiov<strong>as</strong>cularmortality, an eight-fold higher incidenceof peptic ulcers, and a higher risk of someforms of cancer. Other problems includea greater risk of accidents, chronic fatigue,excessive sleepiness, difficulty sleepingand higher rates of substance abuse anddepression. Night-shift workers are alsomuch more likely to view their jobs <strong>as</strong>extremely stressful.So why don’t shift-workers shift theirclocks? After all, if we travel across multipletime zones we do recover from jetlag and entrain to local time. The answerseems to be that the pRGCs that entrainthe circadian system are fairly insensitiveto light. The clock always respondsto bright natural sunlight in preferenceto the dim artificial light commonly foundin the workplace. It is not obvious butshortly after dawn, natural light is some50 times brighter than normal office lighting(300–500 lux), and at noon naturallight can be 500 to 1,000 times brighter– even in Northern Europe. Thus exposureto strong natural light on the journey toand from work, combined with low levelsof light in the workplace, entrains thenight-shift worker onto local time. In thisway biological and social time are persistentlymisaligned in night-shift workers.In the absence of any natural light, however,the clock will eventually respond toman-made light. Theoretically this informationcould be used to develop practicalcounterme<strong>as</strong>ures to the problems ofworking at night. However, most nightshiftworkers prefer not to be adapted toa reversed sleep-wake cycle <strong>as</strong> they liketo spend their work-free time with familyand friends at maximum alertness. Onesuggestion h<strong>as</strong> been to select individualsTable 1Consequences of Circadian RhythmDisruption and Shortened SleepDrowsiness/microsleeps/unintended sleepAbrupt mood shiftsIncre<strong>as</strong>ed irritabilityAnxiety and depressionWeight gainDecre<strong>as</strong>ed socialisation skillsand sense of humourDecre<strong>as</strong>ed motor performanceDecre<strong>as</strong>ed cognitive performanceReduced ability to concentrate and rememberReduced communication and decision skillsIncre<strong>as</strong>ed risk-takingReduced quality, creativity and productivityReduced immunity to dise<strong>as</strong>e and viral infectionFeelings of being chilledReduced ability to handle complext<strong>as</strong>ks or multi-t<strong>as</strong>kIncre<strong>as</strong>ed risk of substance abuse11

Long ph<strong>as</strong>es of human evolutiontook place in bright sunlight.However, this h<strong>as</strong> been changingsince the beginning of the industrialage – with consequences forour health and psyche that areonly gradually becoming knowntoday.for shift work on the b<strong>as</strong>is of their diurnalpreference – ‘owls’ have naturally betteralertness at later hours and make betternight-shift workers, while ‘larks’ are usuallybetter at adapting to early morningshifts.There is incre<strong>as</strong>ing evidence of a complexand important interaction betweencircadian rhythm/sleep disruption andthe immune system. Rats deprived ofsleep readily die of septicaemia, and inhumans the activity of natural killer cellscan be lowered <strong>by</strong> <strong>as</strong> much <strong>as</strong> 28% afteronly one night without sleep. Sleep disruptionalso alters many other <strong>as</strong>pects ofthe immune system including circulatingimmune complexes, secondary antibodyresponses, and antigen uptake. Cortisolprovides an important link between theimmune system, sleep and psychologicalstress. Sleep disruption and sustainedpsychological stress incre<strong>as</strong>e cortisollevels in the blood. Indeed, one lost nightof sleep can raise cortisol <strong>by</strong> nearly 50%on the following evening. High levelsof cortisol act to suppress the immunesystem, so excessively tired people aremore likely to acquire an infection. Inthis context, night-shift workers are at ahigher risk of certain types of cancer andthere h<strong>as</strong> been considerable speculation<strong>as</strong> to the cause. In view of the considerablephysiological stress and sleep loss <strong>as</strong>sociatedwith night-shift work, immuneimpairment could provide a mechanisticlink with the incre<strong>as</strong>ed risk of cancers innight-shift workers.Conclusions and perspectivesThe discussion in this article h<strong>as</strong> consideredboth the biology of internal time andsome of the general problems we face ifwe ignore the role of sleep and circadiantiming in our lives. It is now clear that poorsleep, mood changes, decre<strong>as</strong>ed cognitiveperformance, reduced communicationskills and a higher risk of dise<strong>as</strong>e can arisefrom the demands of a 24/7 society. Oneof the consequences of this impairment ofbrain function is the reliance <strong>by</strong> large sectionsof society on day-time stimulantsand night-time sedatives to replace theorder normally imposed <strong>by</strong> the circadiansystem. Shift-work is perhaps the mostextreme example, but we should not ignorethe fact that many of our childrenin schools, healthcare professionals inhospitals, and manufacturing and businessworkforces are isolated from naturallight. This will not only incre<strong>as</strong>e theirlikelihood of circadian rhythm and sleepdisturbance but also have a significantimpact upon their cognition, mood andsense of well-being. We are a species thath<strong>as</strong> evolved under bright light conditions– even on an overc<strong>as</strong>t day in Europe, naturallight is around 10,000 lux, and may be<strong>as</strong> high <strong>as</strong> 100,000 lux on bright sunnydays. Yet we live in homes and work inoffices, factories, schools and hospitalsthat are often isolated from natural lightand where artificial light is often around200 lux and seldom exceeds 400–500 lux.We live our lives in dim caves. Modern architecturaldesign h<strong>as</strong> the opportunity, <strong>by</strong>letting light into our lives, to liberate humanityfrom the gloom and allowing ourbodies to use the natural pattern of lightand dark to optimise our biology.Russell Foster is Professor of Circadian Neuroscienceand the Head of Department of Ophthalmologyat Oxford University. Russell Foster’sresearch spans b<strong>as</strong>ic and applied circadian andphotoreceptor biology. For his discovery of nonrod,non-cone ocular photoreceptors, he h<strong>as</strong>been awarded numerous prizes, including theHonma prize (Japan), Cogan Award (USA) andZoological Society Scientific & Edride-GreenMedals (UK). He is co-author of Rhythms of Lifeand Se<strong>as</strong>ons of Life, popular science books onbiological rhythms. In 2008, he w<strong>as</strong> elected <strong>as</strong> aFellow of the Royal Society.Further readingFoster, R.G. & Kreitzman, L. (2004) Rhythms of Life:The biological clocks that control the daily lives ofevery living thing. Profile Books, London.Foster, R.G. & Wulff, K. (2005) The rhythm of restand excess. Nat Rev Neurosci, 6, 407–414.Foster, R.G. & Hankins, M.W. (2007) Circadian vision.Curr Biol, 17, R746–751.Rajaratnam, S.M. & Arendt, J. (2001) Health in a24-h society. Lancet, 358, 999–1005.Zaidi, F.H., Hull, J.T., Peirson, S.N., Wulff, K., Aeschbach,D., Gooley, J.J., Brainard, G.C., Gregory-Evans,K., Rizzo III, J.F., Czeisler, C.A., Foster, R.G., Moseley,M.J. & Lockley, S.W. (2007) Short-wavelengthlight sensitivity of circadian, pupillary and visualawareness in humans lacking an outer retina. CurrBiol, 17, 2122–2128.12 D&A SPRING 2011 Issue 15

The Experienceof <strong>Daylight</strong>Views towards the outside are <strong>as</strong>ignificant quality criterion forarchitectural spaces – and notonly in office buildings.A considerable body of research shows that people prefer daylit spacesto those lacking natural light. Why should this be? If there is sufficientlight to see, why would people prefer one source to another? To answerthis question, we need to understand the evolved relationship betweenhumans and natural light.By Judith HeerwagenPhotography <strong>by</strong> Gerry JohanssonImagine you are on a camping trip thatl<strong>as</strong>ts a lifetime. You and your small bandof hunter-gatherers wake up with the firstlight of day. You huddle around the fadingembers of the camp fire, eat leftovers fromthe night before and discuss the day’sforaging activities. By the time the sun isfully up, you head into the bush using thebright light of day to identify edible fruitsand berries and to track animals. By noon,the sun is hot and you seek the shade ofa tree canopy for refuge and rest. As yousnack on nuts and berries, conversationis drawn to the horizon where large stormclouds have begun to gather. You’re a longway from camp and are concerned aboutgetting back. Dark clouds gather, cuttingout the sun overhead but providing dramaticshafts of light in the distance. Itrains hard, but briefly, <strong>as</strong> you huddle undera rock outcropping for protection. Asyou head back, the clouds begin to breakand a rainbow lights up the sky signallingthe end of the storm. You get back to campjust in time for dinner. You discuss theday’s events around the campfire <strong>as</strong> thesun begins to set, lighting the sky orangeand pink. Dusk brings with it a greynessthat hides the details of the landscape,making it more difficult to discern whatis happening beyond the campsite. Soonit is dark and everyone gathers around thefire for warmth, light and companionshipbefore going to sleep under the soft lightof the moon.<strong>Daylight</strong> from anevolutionary perspectivePrior to the advent of buildings, humanslived immersed in nature. Daily activitieswere aided or constrained <strong>by</strong> the presenceor absence of daylight and <strong>by</strong> qualities oflight that signalled time and weather. Ourphysiological systems – especially oursleep-wake cycles – were in synch with thediurnal rhythms of daylight, <strong>as</strong> were ouremotional responses to light and darkness.The strong, consistent preference for daylightin our built-up environments todaysuggests that evolutionary pressures arelikely to be influencing our responses.Although all our sensory systems actingtogether were important to survival,the visual system is our primary mode ofgathering information. Thus, light musthave played a powerful role in informationprocessing and survival. In ancestralhabitats, light w<strong>as</strong> likely to have had severalkey functions that are relevant to thedesign and operation of built-up environments.These include:• Indicator of time. Natural light changessignificantly over the course of the day,providing a signal of time that h<strong>as</strong> beencrucial to survival throughout humanhistory. Being in a safe place when thesun w<strong>as</strong> setting w<strong>as</strong> not a trivial matterfor our ancestors, and it is still importantto human well-being.• Indicator of weather. Light also changeswith weather, from the dark, ominouscolour of storms to rainbows andbeams of light <strong>as</strong> clouds break up andrecede. Attending to the variability inlight and its relationship to changes inweather would have been highly adaptive(Orians and Heerwagen, 1992).• Signal of prospect and refuge. Thesense of prospect is signalled <strong>by</strong> distantbrightness and refuge is signalled <strong>by</strong>shadow (Appleton, 1975, Hildebrand,1999). Brightness in the distance aids<strong>as</strong>sessment and planning because it allowsfor information to be perceived insufficient time for action to be taken.High prospect environments includeopen views to the horizon and a luminoussky (‘big sky’). A sense of refugeis provided <strong>by</strong> shadows from tree canopies,cliff overhangs, or other naturalforms. Mottram (2002) suggests thatallowing the eyes to rest on infinity(which the horizon represents visually)may be beneficial, even if the viewis perceptually manipulated throughvisual images rather than actual distantviews. Thus, our natural attractionto the horizon could be satisfied inmany ways through the manipulationof light and imagery applied to verticalsurfaces.• Signal of safety, warmth, and comfort.Although we usually think of the sun<strong>as</strong> the primary source of light in thenatural environment, fire also served<strong>as</strong> a source of light and comfort, bothphysical and psychological. Anthropologistand physician Melvin Kon-15

There is an innate need inhuman beings to be in touchwith nature. The acceptanceof buildings is therefore cruciallydependent on the extent towhich they enable contact withexternal surroundings.ner (1982) suggests that the campfireserved important cognitive and socialfunctions in developing human societies.The campfire extended the day, allowingpeople to focus their attentionnot only on the daily grind of findingfood and avoiding predators but alsoon thinking about the future, planningahead and cementing social relationshipsthrough story-telling and sharingthe day’s experiences.• Peripheral processing aid. Light alsoprovides information about what ishappening beyond the immediatespace one occupies. It illuminatesthe surrounding environment that impingescontinually on our peripheralprocessing system. The importance ofperipheral light is evident from the discomfortmany people feel when theyare in a lighted space with low lightingat the edges, leading to a perception ofgloom. Lighting researchers suggestthat negative responses to gloom maybe <strong>as</strong>sociated with its natural function<strong>as</strong> an early warning signal that visualconditions are deteriorating (Shepherdet al, 1989).• Synchronisation of bio- and socialrhythms. As a diurnal species, lightplays a critical role in our sleep-wakecycles and also synchronises social activities.Although we can now alter ouractivity cycle with the use of electriclight, research evidence nonethelessshows that night work is still difficultand often results in drowsiness, difficultysleeping, mood disturbancesand incre<strong>as</strong>ed cognitive difficulties atwork (Golden et al, 2005). Some nightwork facilities are using bright interiorlight to shift biological rhythmsand incre<strong>as</strong>e alertness. There is alsoevidence that people who experiencese<strong>as</strong>onally-related depression preferto be in brightly lit spaces (Heerwagen,1990).To summarise, light provides informationfor orientation, safety and surveillance,interpretation of social signals, identificationof resources and awareness of hazards.Whether it is the changing colour oflight <strong>as</strong>sociated with sunset or storms, themovement of fire or lightning, the brightnessin the distance that aids planning andmovement, or the sparkle of light off water– all these <strong>as</strong>pects of light have played a rolein helping our ancestors make decisionsabout where to go, how to move throughthe environment, what to eat, and how toavoid dangers.Human experience of daylight inthe built-up environmentGiven Homo sapiens immersion in anaturally-lit environment during ourevolutionary history, it is not surprisingthat building occupants enjoy the veryfeatures that characterise daylight innatural landscapes.Research on office buildings shows ahigh preference for daylit spaces and forspecific features of daylight. A study ofseven office buildings in the Pacific Northwest(Heerwagen et al, 1992) shows thatmore than 83% of the occupants said they“very much” liked daylight and sunlight intheir workspace, and valued the se<strong>as</strong>onalchanges in daylight. Interestingly, daylightdesign generally aims to eliminatedirect beam sunlight from entering workare<strong>as</strong> due to glare and heat gain.When the data were looked at with respectto the occupant’s location, 100% ofthose in corner offices said the amount ofdaylight w<strong>as</strong> “just right,” <strong>as</strong> did more than90% of those along the window wall inspaces other than the corner offices. Eventhose located in more interior positionswere satisfied with the daylight, <strong>as</strong> long<strong>as</strong> they could look into a daylit space.<strong>Daylight</strong> and workWe know that people like to be in daylitspaces and that they like indoor sunlight.However, when occupants in the abovestudy were <strong>as</strong>ked about light for workpurposes, only 20% said daylight w<strong>as</strong>sufficient for work. The v<strong>as</strong>t majority saidthey used electric ceiling light “usually” or“always” to supplement daylight.Even those who rated daylight <strong>as</strong> “justright” also used electric lights regularly.Although the re<strong>as</strong>ons for this situationare not clear, anecdotal evidence suggests19

Views towards the outside areamong the most important criteriafor the acceptance of buildings.While providing varietywithin the everyday routine oflife, they also help to preventfeelings of claustrophobia.that occupants also supplement daylightwith t<strong>as</strong>k lamps. It is possible that electriclight, whether ceiling or t<strong>as</strong>k, reduceslighting contr<strong>as</strong>ts on work surfaces thatmake some visual work difficult.A post-occupancy evaluation of thefirst LEED Platinum building in the US,the Philip Merrill Environmental Center,shows very high satisfaction with daylight,despite concerns with visual discomfort(Heerwagen and Zagreus, 2005). Thissuggests that people may value the psychologicalbenefits of daylight even whendaylight creates difficulties for work dueto glare and uneven light distribution.Certainly, the kinds of visual t<strong>as</strong>ks weperform in today’s work environmentsare very different from our ancestors’daily t<strong>as</strong>ks. Cooking, tool making, conversing,foraging, and hunting could beeffectively carried out over a wide rangeof luminous conditions. In contr<strong>as</strong>t, readingand computer work require a muchgreater degree of visual acuity that maybe more difficult in some daylit environments.Yet a uniformly lit environmentthat may be appropriate for office worklacks the psychological, and perhaps biological,value of daylight.Attitudes toward <strong>Daylight</strong> andElectric LightA study of office workers in a Seattlehigh-rise building <strong>as</strong>ked respondents tocompare the relative merits of daylightand electric light for psychological comfort,general health, visual health, workperformance, jobs requiring fine observation,and office aesthetics (Heerwagenand Heerwagen, 1986).The results show that the respondentsrated daylight <strong>as</strong> better than electric lightfor all variables, especially for psychologicalcomfort, health and aesthetics. Theyrated daylight and electric light <strong>as</strong> equallygood for visual t<strong>as</strong>ks.At the time of this study in 1986, therew<strong>as</strong> little evidence connecting daylight tohealth. Since that time, however, thereh<strong>as</strong> been a surge of research on the link betweenlight and health, much of it focusingon the circadian system and se<strong>as</strong>onalaffective disorder. Much of this work h<strong>as</strong>been conducted in clinical settings withphototherapy. Since a review of this topicis provided elsewhere in this issue, it willnot be addressed here.However, it is worth noting a laboratorystudy that investigated lighting preferencesof subjects with Se<strong>as</strong>onal AffectiveDisorder (SAD) compared to subjects thatdid not experience se<strong>as</strong>onal changes inmood or other behaviours (Heerwagen,1990). Those who experienced se<strong>as</strong>onalchanges chose significantly higher levelsof brightness for all lighting sources comparedto those who did not. This suggeststhat people experiencing SAD may indeedbe ‘light hungry’ and could benefit fromindoor environments with high daylightlevels, such <strong>as</strong> atria, sunrooms and locationsadjacent to windows.But what do we know about otherhealth impacts of daylight in the builtupenvironment? Research in hospitalsettings, looking at the relationship betweenroom daylight levels and patientoutcomes, found that bi-polar patientsin bright, e<strong>as</strong>t-facing rooms stayed in thehospital 3.7 fewer days on average thanthose in west-facing rooms (Benedettiand others, 2001). Similar results werefound <strong>by</strong> Beauchamin and Hays (1996)for psychiatric in-patients; those in thebrightest rooms stayed in the hospital 2.6fewer days on average. However, neitherof these studies provides data on the actuallight levels in the patient rooms or lightentering the retina, so it is difficult to drawconclusions about exposure levels.More recent research in a Pittsburghhospital actually me<strong>as</strong>ured room brightnesslevels. Walch and others (2005) studied89 patients who had elective cervicaland spinal surgery. Half the patientswere located on the bright side of thehospital, while the other half were in ahospital wing with an adjacent buildingthat blocked sun entering the rooms. Thestudy team me<strong>as</strong>ured medication typesand cost <strong>as</strong> well <strong>as</strong> psychological functioningthe day after surgery and at discharge.The researchers also conducted extensivephotometric me<strong>as</strong>urements of light ineach room, including light levels at thewindow, on the wall opposite the patient’sbed, and at the head of the bed (which presumablywould have been at or near the20 D&A SPRING 2011 Issue 15

Natural light at the place of workis not only a question of seeing.Surveys have shown that peopleplace great value on daylighteven when it is actually detrimentalto vision.patient’s eye level). The results showedthat those in the brighter rooms had 46%higher intensity of sunlight. Patients inthe brightest rooms also took 22% lessanalgesic medicine/hr and experiencedless stress and marginally less pain. Thisresulted in a 21% decre<strong>as</strong>e in the costs ofmedicine for those in the brightest rooms.The mechanisms linking bright light topain are currently unknown, however.Other potential benefits of indoor daylightinclude improved sense of vitality, decre<strong>as</strong>eddaytime sleepiness and reducedanxiety. For example, a large-scale surveyof office worker exposure to light duringthe winter in Sweden shows that moodand vitality were enhanced in healthypeople with higher levels of exposure tobright daylight (Partonen and Lönngvist,2000). Another study shows that a halfhourexposure to bright daylight <strong>by</strong> sittingadjacent to windows reduced afternoonsleepiness in healthy adult subjects (Kaidaet al., 2006). In that study, daylight levelsranged from about 1,000 lux to over 4,000lux, depending upon sky conditions. Kaidaet al. found that daylight w<strong>as</strong> almost <strong>as</strong>effective <strong>as</strong> a short nap in reducing normalpost-lunchtime drowsiness and incre<strong>as</strong>ingalertness.Is daylight biophilic?E.O. Wilson popularised the term “biophilia”in 1984 with the publication ofhis book, Biophilia. In it he describes biophilia<strong>as</strong> the human tendency to affiliatewith life and life- like processes. Wilsonnever fully explained what he meant <strong>by</strong>“life-like processes.” However, if we considerthe characteristics of life, we canlook at daylight <strong>as</strong> sharing some of thesefeatures. <strong>Daylight</strong> grows over the courseof the day <strong>as</strong> the sun moves across thesky, it changes in colour and intensity, itprovides sustenance for life, its absenceat night provokes behavioural change,and the lengthening day after the longwinter months evokes joy and a sense ofwell being.Wilson and others describe biophilia<strong>as</strong> an evolved adaptation linked to survival.The evidence cited in this articlesuggests that daylight, in addition to being“life-like,” h<strong>as</strong> deeply-seated healthand psychological benefits that may bedifficult to support in electrically-litenvironments. Clearly, we can designinteriors with electric light that changesintensity and colour over time and thatmimics other features of daylight. But willit feel the same? Can electrically-lit environmentsprovide the same biologicalbenefits <strong>as</strong> daylight? We don’t yet knowthe answers to these questions, but wedo know that such efforts would be moreenergy intensive and more costly.The life-like and life-supportingqualities of daylight strongly suggestthat daylight is a b<strong>as</strong>ic human need, nota resource to be used or eliminated at thewhim of the building owner or designer.The presence of daylight and sunlight inbuildings clearly affects our psychologicaland physiological experience of place. Itsabsence creates lifeless, bland, indifferentspaces that disconnect us from ourbiological heritage.Judith Heerwagen, Ph.D., is an environmental psychologistin Seattle, W<strong>as</strong>hington. She is an affiliatefaculty member in the Department of <strong>Architecture</strong>at the University of W<strong>as</strong>hington where she h<strong>as</strong> cotaughtseminars on bio-inspired design and sustainability.She h<strong>as</strong> written and lectured widely onthe human factors of sustainable design, includinghealth, psychological impacts and productivity.She is co-editor of Biophilic Design: The Theory,Science and Practice of Bringing Buildings to Life(Wiley, 2008).ReferencesAppleton, J. 1975. The Experience ofLandscape. London: Wiley.Beauchemin, K.M. and Hayes, P.1996. Sunny hospital rooms expediterecovery from severe and refractorydepressions. Journal of Affective Disorders,40(1): 49–51.Benedetti, F., Colombo, C., Barbini, B.,Campori, E., and Smeraldi, E., 2001.Morning sunlight reduces length ofhospitalization in biopolar depression.Journal of Affective Disorders,62(3): 221–223.Golden, R.N., Gaynes B.N., Ekstrom,R.D., Hamer, R.M., Jacobsen, R.M.,Suppes, T., Wisner, K.L. and Nemeroff,C.B. 2005. The efficacy of light therapyin the treatment of mood disorders:a review and meta-analysis ofthe evidence. American Journal ofPsychiatry, 162: 656–662.Heerwagen, J.H. 1990. Affective Functioning,“Light Hunger,” and RoomBrightness Preferences. Environmentand Behavior. 22(5): 608–635.Heerwagen, J. H. and Heerwagen,D.R. 1986. Lighting and PsychologicalComfort. Lighting Design and Application,16(4): 47–51.Heerwagen, J.H. and Zagreus, L.2005. The Human Factors of Sustainability:A Post Occupancy Evaluationof the Philip Merrill EnvironmentalCenter, Annapolis MD. University ofCalifornia, Berkeley, Center for theBuilt Environment.Heerwagen, J.H. and Orians, G.H1993. Humans, Habitats and Aesthetics.In Kellert, S.R. and Wilson,E.O. (Eds.) The Biophilia Hypothesis.W<strong>as</strong>hington DC: Island Press.Hildebrand, G. 1999. Origins of ArchitecturalPle<strong>as</strong>ure. Berkeley: Universityof California Press.Kaida, K., Takahshi, M., Haratani, T.,Otsuka, Y., Fuk<strong>as</strong>awa, K. and Nakata,A. 2006. Indoor exposure to naturalbright light prevents afternoon sleepiness.Sleep, 29(4): 462–469.Konner, M. 1982. The Tangled Wing:Biological Constraints on the HumanSpirit. NewYork: Holt, Rhinehart &WinstonMottram, J. 2002. Textile Fields andWorkplace Emotions. Paper presentedat the 3rd International Conferenceon Design and Emotion, 1–3July, Loughborough, England.Orians, G.H. and Heerwagen, J.H.1992. Evolved Responses to Landscapes.In Barkow, J., Cosmides, L.and Too<strong>by</strong>, J. (Eds). The AdaptedMind: Evolutionary Psychology andthe Generation of Culture. New York:Oxford University Press.Partonen, T. and Lönngvist, J. 2000.Bright light improves vitality andalleviates distress in healthy people.Journal of Affective Disorders,57(1): 55–61.Shepherd, A.J., Jullien, W.G. and Purcell,A.T. 1989. Gloom <strong>as</strong> a psychophysiologicalphenomenon. LightingResearch and Technology, 21(3): 89–97.Walch, J. M., Rabin, B. S., Day, R., Williams,J. N., Choi, K. and Kang, J. D.2005. The effect of sunlight on postoperativeanalgesic medication use: aprospective study of patients undergoingspinal surgery. PsychosomaticMedicine, 67: 156–163.Wilson, E.O. 1984. Biophilia. Cambridge,MA: Harvard UniversityPress.22 D&A SPRING 2011 Issue 15

Imagining Light:the me<strong>as</strong>ureableand the unme<strong>as</strong>urableof daylight designThe art of daylighting involves much more than merely allowing the rightamounts of natural light into a building. Acts of great architecturalimagination may transform the utilitarian functions of daylighting – theme<strong>as</strong>urable – into places of great beauty – the unme<strong>as</strong>urable. To get abetter understanding of these strategies, it is helpful to look at m<strong>as</strong>terpiecesof daylight and architecture in greater detail.By Dean HawkesPhotography <strong>by</strong> Gerry Johansson“<strong>Architecture</strong> comes from the making ofa room. A room is not a room withoutnatural light.”Louis KahnIn this deceptively simple statement,Louis Kahn lays down a profound challenge.The implication is that light inarchitecture is needed not only to servepractical purposes, but is the key to thedefinition of architecture itself.One of the most important achievementsof nineteenth- and twentieth-centuryapplied science h<strong>as</strong> been to quantify andcodify human requirements in buildings.This h<strong>as</strong> been particularly successful inthe field of lighting design, where standardsof illumination, design proceduresand rules-of-thumb are to be found inmany design manuals and guidebooksFamiliar rules-of-thumb include geometricalformulae, such <strong>as</strong> the ‘no-skyline’, where the depth of penetration ofthe visible sky is taken to indicate thelimitation of the daylit area of a room.Others are expressed in simple equationsin which the daylight factor in a room isrelated to the ratio of window area to floorarea. These tools are of immense utilityand place practical design on solid foundations.In recent years, they have beencomplemented <strong>by</strong> the development ofcomputer-b<strong>as</strong>ed calculation methodsand simulation tools.But there is much more to daylightingdesign than this and, once again, it is LouisKahn who gets to the nub of the matter.“I only wish that the first really worthwhilediscovery of science would be that it recognisedthat the unme<strong>as</strong>urable is whatthey’re really fighting to understand, andthat the me<strong>as</strong>ureable is only the servantof the unme<strong>as</strong>urable; that everything thatman makes must be fundamentally unme<strong>as</strong>urable.”Here Kahn presents a conundrum. Whatis the value of quantification and codification,the me<strong>as</strong>ureable, if we are reallyseeking to understand the essence of architecture,the unme<strong>as</strong>urable? How maywe solve the puzzle?It is a truism that architecture is acombination of art and science. This isclearly reflected in the conventional categoriesof architectural literature and inthe curricula of schools of architecture,where the two realms all too often remainfirmly separate. But this does not help usto solve Kahn’s conundrum, so where dowe look?Christopher Wren:geometry and lightMy solution is that, whilst <strong>as</strong>pects of artand science certainly pertain to questionsof architecture, it is not possible to constructa proper understanding of its truenature <strong>by</strong> applying a simplistic equationof the form – art + science = architecture.In the search for an answer, we shouldturn to the evidence of buildings themselves,of works of architecture, and ofthe statements of architects of substance,which, if correctly interpreted, providedeep insights into the matter. I propose amode of architectural analysis that allowsus to look directly into Kahn’s architecturalunme<strong>as</strong>urable.In my book The Environmental Imagination,I made studies of works <strong>by</strong> significantarchitects whose work spannedthe nineteenth and twentieth centuries,precisely paralleling the period whenthe quantification of environmentaldesign occurred. In recent work, I havepushed back the historical time frameto explore works from the sixteenth tothe eighteenth centuries. In all of this Ihave argued that the crucial instrumentof understanding, of looking into the unme<strong>as</strong>urable,is that of the imagination,defined <strong>by</strong> my dictionary <strong>as</strong>, ‘the facultyof forming new ide<strong>as</strong>’. To illustrate mymeaning, let’s consider some buildingsthat demonstrate the application of imaginationin the conception of daylight.The first c<strong>as</strong>e is from the works of SirChristopher Wren. He w<strong>as</strong> both scientistand architect and, before his first works<strong>as</strong> an architect, he held professorships of<strong>as</strong>tronomy, first in London and then inOxford. In a forthcoming book I explorethe relationship between Wren’s scienceand his architecture and propose that heachieved a profound reconciliation ofthese two fields, of the me<strong>as</strong>urable andthe unme<strong>as</strong>urable. One of Wren’s greatestarchitectural achievements w<strong>as</strong> thereconstruction of over fifty Londonchurches, following the dev<strong>as</strong>tation of the27

cd/m 28000580041003000210015001100800

The false-colour images in this articleshow the luminance distributionin the depicted spaces. Luminance(me<strong>as</strong>ured in candela per squaremetre) is an indicator for the ‘brightness’of a surface and therefore animportant quantitative me<strong>as</strong>ure ofthe distribution of light in a room.The human eye can adapt to widevariations in luminance: while theclear sky, on average, h<strong>as</strong> a brightnessof 8000 cd/m2, a computermonitor only emits light with a luminanceof some 50-300 cd/m2.P.26–30 In the central exhibitionroom of the Museo Canoviano inPossagno, Carlo Scarpa designedthe windows <strong>as</strong> independent, pl<strong>as</strong>tic‘light bodies’. The cubic gl<strong>as</strong>s elementsnot only light up the interiorbut also produce directed glancinglight on the walls, thus emph<strong>as</strong>isingthe surface structure of pl<strong>as</strong>ter andnatural stone even more clearly.A luminance map showing the distributionof luminous intensities inthe room.Great Fire of 1666. Perhaps the greatestof these is the church of St. Stephen Walbrook(1672–1680). Here a simple rectangularplan is enclosed <strong>by</strong> a cross sectionthat plays upon the juxtaposition of anaisled and a centralised plan. This leadsto great complexity of space and light.The illumination from large windowsis supplemented <strong>by</strong> arched clerestoriesoriented to north, south, e<strong>as</strong>t and westand <strong>by</strong> the lantern that surmounts thedome. Wren w<strong>as</strong> f<strong>as</strong>tidious in providingthe practical illumination needed for actsof worship, but his intentions extendedbeyond the practical. As the historianKerry Downes writes of St. Stephen;“Wren considered geometry to be the b<strong>as</strong>isof the whole world and the manifestation ofits Creator, while light not only made thatgeometry visible, but also represented thegift of Re<strong>as</strong>on, of which geometry w<strong>as</strong> forhim the highest expression.”In the building, the alternating patternsof light and shade, the sudden and briefillumination of the shaft of a column, thatreshape the space from hour to hour andfrom se<strong>as</strong>on to se<strong>as</strong>on reveal that Wren’sscientific understanding of light w<strong>as</strong> fusedwith a remarkable imagination.Soane and Scarpa:poets of daylightAnother English architect whose workexhibits an imagination equal to that ofWren is Sir John Soane. He worked at thetime when the industrial revolution w<strong>as</strong>transforming the technologies of buildingand w<strong>as</strong> greatly interested in these, but he,like Wren, w<strong>as</strong> simultaneously engagedwith the qualitative <strong>as</strong>pects of light inarchitecture.“The ‘lumière mystérieuse’ so successfullypractised <strong>by</strong> the French artists, is a mostpowerful agent in the hands of a man ofgenius, and its power cannot be too fullyunderstood, nor too highly appreciated. Itis, however, little attended to in our architecture,and for this obvious re<strong>as</strong>on, thatwe do not sufficiently feel the importanceof character in our buildings, to which themode of admitting light contributes in nosmall degree.”In the design of his house at 12–14 Lincoln’sInn Fields in the centre of London,which he occupied and transformed inthe years from 1792 until his death in 1837,Soane seized the opportunity to explorethe character of natural light to sustainboth the practical and poetic needs ofthe act of dwelling. These were met <strong>by</strong>the richest and most diverse architecturalmeans, combining side lighting withrooflights simultaneously to achieve bothpractical and poetic ends. The library anddrawing room are interconnected spacesat the ground floor of the main body of thehouse. The library lies behind the principal,south-facing façade and the diningroom is lit from an open courtyard to thenorth. The walls of both rooms are a deepPompeian red. This absorbs much of thelight that enters, but ample compensationcomes from the arrays of large and smallmirrors that supplement and transformboth the quality and quantity of the light.Some of the most significant of these arethose that face the piers of the glazed loggiato the south and the sliding shutters atthe windows. By these means, the roomsare simultaneously sombre and sparkling,lumière mystérieuse brought to the serviceof domestic life and of architecture.Moving to examples from the twentiethcentury, Boris Podrecca h<strong>as</strong> writtenthat,“In (Carlo) Scarpa’s work it is not just thephysical presence of things that transfigurestradition, but also the light, which is alumen not of tomorrow but of the p<strong>as</strong>t – thelight of the golden background, of the glimmeringliquid, of the ivory-coloured inlay,of luminous and shimmering fabrics recreatedin marble. It is the light of a reflectionof the world.”These qualities are fully demonstratedin the tiny addition that Scarpa built tothe Museo Canoviano at Possagno in the1950s. The composition pivots around atall cubic space lit <strong>by</strong> four trihedral cornerwindows placed at the intersection of walland roof. Two of these face west and aretall and the glazing is concave, the othersare to the e<strong>as</strong>t and the gl<strong>as</strong>s enclosure isconvex. This configuration captures lightfrom all orientations and, unlike a con-30 D&A SPRING 2011 Issue 15

cd/m 22009444219,74,52,11

cd/m 2200120704124148,55The ‘Heelis’ office building,which Feilden Clegg Bradleydesigned for the British NationalTrust not far from Swindon railwaystation, takes its inspirationfrom the locomotive sheds in thevicinity. The deep office are<strong>as</strong>are illuminated almost exclusivelythrough the roof ratherthan through the facades, providingviews to the sky.Luminance map showing the distributionof luminous intensitiesin the room.Previous spread Quadratic rooflights and large façade windowsilluminate the Yale Center forBritish Art <strong>by</strong> Louis Kahn.They immerse the interior in adimmed light that is typical ofEngland – the country wheremost of the paintings on showhere originated. A luminancemap showing the distribution ofluminous intensities in the room.ventional window set in a wall, c<strong>as</strong>ts lightacross the walls themselves. As the sunmoves around the building, the interiorand Canova’s precious and wonderfulpl<strong>as</strong>ter figures that it contains become animatedin the ever-changing illumination,presenting them to the observer almost<strong>as</strong> living beings. The corner window w<strong>as</strong>an invention of the modern movement;one thinks of Wright’s Prairie houses andRietveld’s Schroeder House, but Scarpa’simagination invested it with new meaningand value. Speaking about the projectin 1978, Scarpa declared, “I really lovedaylight: I wish I could frame the blue ofthe sky.” In this bejewelled building, heachieved that wish in full me<strong>as</strong>ure.Buildings for all purposesAs one would expect, Louis Kahn madesome of the most important contributionsin reconciling the practicalitiesand poetics of light in architecture. Anyof his mature buildings would serve todemonstrate this and I have chosen theYale Center for British Art (1969–1974).The building is an austere composition ofexposed concrete frame, clad in stainlesssteel and lined with panels of Americanoak and white pl<strong>as</strong>ter. It w<strong>as</strong> conceived tobe daylit – “a room is not a room withoutnatural light” – and the entire roof planeis covered <strong>by</strong> a system of square rooflights.The perimeter galleries also bring in sidelightfrom carefully positioned windows.Many of the paintings in the collectionwere first hung in English country housesand they often depict English scenes underthe light of English skies. Kahn performsa remarkable trick of architecturalmagic <strong>by</strong> creating the illusion of just sucha setting under the very different skies ofConnecticut. The layered design of therooflights, which have external louvresand internal diffusing filters, subduesthe bright light to render it appropriatelysubfusc <strong>as</strong> it plays on the restrained architectureof the interior. Kahn’s extensivestudy drawings show that these effectswere the product of meticulous analysis.A living m<strong>as</strong>ter of imaginative light isPeter Zumthor. In the sequence of buildingsthat he h<strong>as</strong> built in the l<strong>as</strong>t quarter of acentury, he exhibits a special awareness ofhow the material of building may be f<strong>as</strong>hionedto capture and project daylight inthe service of the uses of his buildings. Heh<strong>as</strong> written,“[One] of my favourite ide<strong>as</strong> is this: to planthe building <strong>as</strong> a pure m<strong>as</strong>s of shadow then,afterwards to put in the light <strong>as</strong> if you werehollowing out the darkness, <strong>as</strong> if the lightwere a new m<strong>as</strong>s seeping in.The second idea I like is this: to go aboutlighting materials and surfaces systematicallyand to look at the way they reflect thelight. In other words, to chose the materialsin the knowledge that they reflect andfit everything together on the b<strong>as</strong>is of thatknowledge.”The translation of these ide<strong>as</strong> is wonderfullydemonstrated in the Shelter for RomanRemains at Chur, completed in 1986.This deceptively simple building consistsof three rooflit volumes that trace the outlinesof the fragmentary remains of theRoman structure. The timber-framedstructure is clad with timber lamella andthe zinc-covered roof is punctured <strong>by</strong>three large rooflights. But this tectonicsimplicity conceals a deep understandingof the nature and behaviour of light. Thewalls are opaque to vision, but nonethelesstransmit light <strong>by</strong> the process of interreflectionthrough the lamella. The effectis to bring a diffuse glow to the interior,the light warmed <strong>by</strong> the tone of the timber.This is then dramatised and transformed<strong>by</strong> the powerful zenithal lightthat c<strong>as</strong>cades from the rooflights. Thetall <strong>as</strong>ymmetrical linings of the rooflightopenings are, unusually, painted blackand this starkly intensifies their light <strong>as</strong>it falls upon the pale grey gravel of thefloor. All this is a clear consequence of thearchitect’s systematic, objective considerationof the interaction between lightand material. The effect is spellbindingand original.The codification of the environmentin buildings evolved hand-in-glove withthe development of the highly engineeredbuilding types of the twentieth century.The office building is, perhaps, the mostfamiliar and, to some extent the most successfulc<strong>as</strong>e in which mechanical plant35

Peter Zumthor’s shelter forRoman remains in Chur consistof three cubic structures cladwith wooden slats. Diffuse daylighttrickles into the interiorthrough the diaphanous buildingskin. The main light accents,however, are created <strong>by</strong> large‘light cannons’ in the roof,located in the centre of eachspace, diagonally to the patternof the construction.Following pages In the church ofSt. Stephen Walbrook in London,Christopher Wren combined thesymmetry and rigid geometry ofRenaissance architecture withthe metaphysics of light. Largewindows in all four facades provideb<strong>as</strong>ic lighting, while theclerestory windows and the lanternin the cupola c<strong>as</strong>t individualrays of light that wanderthrough the interior during thecourse of the day. A luminancemap showing the distribution ofluminous intensities in the room.h<strong>as</strong> become ubiquitous and artificial lighth<strong>as</strong> replaced daylight <strong>as</strong> the principal illumination.There are, however, importantexceptions to this rule. One such is theHeelis Building at Swindon in southernEngland. This is the headquarters of theNational Trust, the custodian of muchof England’s architectural heritage; thebuilding, completed in 2005, is the workof architects Feilden Clegg Bradley.The building is on the site of formerrailway yards that were first developed<strong>by</strong> the great nineteenth-century engineerIsambard Kingdom Brunel. In itsform it refers to the original industrialbuildings. It h<strong>as</strong> a deep plan covered <strong>by</strong>a series of pitched roofs that provide copiousquantities of daylight and promotenatural ventilation. They also supportarrays of photovoltaic cells to generatevaluable electricity. Beneath the roof,two-storey office wings with mezzaninesalternate with double-height communaland social places. The design intentionw<strong>as</strong> to provide natural light to all theworkplaces. The simple strategy w<strong>as</strong> toensure that every workplace h<strong>as</strong> a directview of the sky. The standard ‘designsky’ used in quantitative design is threetimes brighter at the zenith than at thehorizon. This means that ‘skylight’ is abetter source than side lighting. In additionit is a well-understood empiricalfact of daylighting under the English skythat a view of the sky provides adequateillumination for most practical purposes.These principles are elegantly applied atthe Heelis building, where daylight factorsrange from 3 per cent beneath themezzanine floors to an average of 9 percent on the mezzanines. In the doubleheight spaces, the light is allowed freerein and is animated <strong>by</strong> patches of sunlightthat play over surfaces and bring adynamic connection with outside natureinto the heart of this deep plan building.In its practicality and artfulness the buildingbecomes an appropriate symbol of theNational Trust’s mission.Each of these buildings addresses specificand often specialised needs, be theyacts of Christian worship, dwelling in thenineteenth-century city, the display andconservation of rare neo-cl<strong>as</strong>sical sculpture,the public display of British art inAmerica, the protection of fragile Romanremains, or the practical and social needsof corporate headquarters. In every c<strong>as</strong>eobjective needs of shelter, protection andillumination are met, but what drawsthem to our attention is the manner inwhich the ordinary is made extraordinary<strong>by</strong> acts of architectural imagination.However, this process is equally relevantin designing buildings that maybe thought to be ‘everyday’. There is almostno function in a building, institution,workplace or home, that may not be improved<strong>by</strong> taking place in a room in whichquantitative adequacy is complemented<strong>by</strong> carefully conceived gradations of lightand shade, an awareness of the daily andse<strong>as</strong>onal cycles of the sun or the rich interplaybetween light and the form andmateriality of a room. These are thetools <strong>by</strong> which the imagination may helpus bridge the gap between Louis Kahn’sme<strong>as</strong>urable and unme<strong>as</strong>urable. It is thusthat buildings may become works of architecture.Dean Hawkes (b. 1938) is an architect and teacher.He is emeritus professor of architectural designat the Welsh School of <strong>Architecture</strong>, Cardiff Universityand emeritus fellow of Darwin College,University of Cambridge. His books include TheEnvironmental Imagination (2008) and <strong>Architecture</strong>and Climate (to be published in 2011).His buildings have won four RIBA <strong>Architecture</strong>Awards. In 2011, he received the RIBA’s internationalbiennial Annie Spink Award for excellencein architectural education.38 D&A SPRING 2011 Issue 15

cd/m 220105,42,81,40,750,390,2

In search of ananthropologyof daylightFor centuries, architects havebeen working on ways of capturingthe magic of daylight inbuildings. They are supported inthis <strong>by</strong> a continually expandingrange of building materials.In contemporary urban environments, daylight is incre<strong>as</strong>inglybeing restricted and supplemented with artificial light, resultingin a loss of connectedness to the natural environment. If ourphysiological and the psychological expectations are to be met,architecture will need to develop fresh techniques in workingwith daylight, <strong>as</strong> well <strong>as</strong> create a closer dialogue with science,in order to achieve a true state of well-being in people.By Brent RichardsPhotography <strong>by</strong> Gerry JohanssonTOWARDS THE LIGHT<strong>Daylight</strong> from a human perspective isgoverned <strong>by</strong> an intrinsic need to be in thelight and not the dark, to be in the warmthof sunlight and not the cool of shadows.This need is also governed <strong>by</strong> an innatedesire for physical and emotional interactionwith daylight. These interactions canrange from the haptic response of feelingdaylight on our skin, or sensing the pathof daylight from sunrise to sunset, to theperception of seeing the light of the skyabove or the vista beyond. 1 <strong>Daylight</strong> notonly influences the sensorial <strong>as</strong>pects inrelation to our mood – it also affects ourbehaviour and overall sense of well-being,subject to time of day and geographicalcontext.Prior to man dwelling in caves, heroamed the savannah living a nomadiclifestyle in the open, reliant on daylight tofind food and for safety from wild animals.Humans inhabited a natural world governedprecisely <strong>by</strong> the pattern of day andnight. This light and dark cycle framed theflow of daily activities and established afundamental relationship between the“<strong>Daylight</strong> does not behave in alinear f<strong>as</strong>hion, but forever playsrecurrent games of days and of these<strong>as</strong>ons <strong>as</strong> the earth rotates on itsaxis and follows its orbit aroundthe sun”Ole Boumanphysiological and psychological rhythmsof man to his habitat. In many culturesthis relationship w<strong>as</strong> the b<strong>as</strong>is for mysticismand religious worship – and light w<strong>as</strong>considered sacred.When humans evolved to constructingearly buildings, they sought to reinforcethe connection with the outside world <strong>by</strong>positioning primitive openings and windows.These purpose-built apertures providednot only access to daylight and freshair but also a symbolic interface betweeninside and outside. Furthermore, they attunedhuman dwelling habits to the dailyrituals of living and to sleep-wake cycles,synchronising the rhythms of light to thetwenty-four hour cycle.Given this fundamental symbiosisbetween humans and daylight, the languageof architecture h<strong>as</strong> exploited theinterplay between the built environmentand the naturally-lit interior. <strong>Architecture</strong>h<strong>as</strong> become adept at maximisingthe comfort-giving qualities of light, emph<strong>as</strong>isingthe visual focus and connection,whilst contributing to the sense ofwell-being. <strong>Architecture</strong>’s objective h<strong>as</strong>been to capture, enhance and articulatedaylight using the building’s componentsto filter, reflect, mediate and redirectlight. In doing so, architects achievedcontrol over the luminosity, brightnessand contr<strong>as</strong>t of light between outside andinside, <strong>as</strong> well <strong>as</strong> the relationship of lightto interior functions. This relationship todaylight h<strong>as</strong> remained a strong elementthroughout the history of architecture,“The allure of daylight is that itbecomes the most enduring ofmemories, which touches ourdeepest perception and emotions,and affects our notion of time andplace. Light falling on the object ofarchitecture does not tell thewhole story; it creates an emergentand transient state thatdraws a veil over architecture’sform. Notions of space, transparency,lightness and darkness, solidand void, all emanate from thismemoryscape that stirs the sensesand brings equilibrium to ourbeing.”Brent Richards43