New Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain

New Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain

New Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

The <str<strong>on</strong>g>New</str<strong>on</strong>g><str<strong>on</strong>g>Drawing</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong><strong>Right</strong> <strong>Side</strong> <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong> <strong>Brain</strong>

Also by <strong>the</strong> author:<str<strong>on</strong>g>Drawing</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> Artist Within

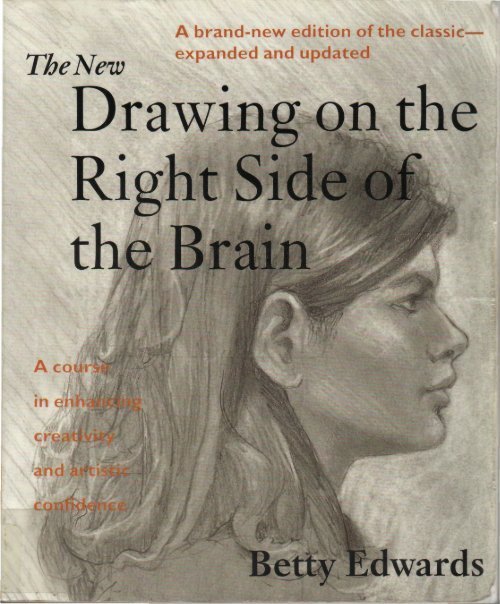

The <str<strong>on</strong>g>New</str<strong>on</strong>g><str<strong>on</strong>g>Drawing</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong><strong>Right</strong> <strong>Side</strong> <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong> <strong>Brain</strong>Betty EdwardsJeremy P. Tarcher/Putnama member <strong>of</strong>Penguin Putnam Inc.<str<strong>on</strong>g>New</str<strong>on</strong>g> York

Most Tarcher/Putnam books are available at special quantity discounts for bulkpurchase for sales promoti<strong>on</strong>s, premiums, fund-raising, and educati<strong>on</strong>al needs.Special books or book excerpts also can be created to fit specific needs. For details,write Putnam Special Markets, 375 Huds<strong>on</strong> Street, <str<strong>on</strong>g>New</str<strong>on</strong>g> York, NY 10014.Jeremy P. Tarcher/Putnama member <strong>of</strong>Penguin Putnam Inc.375 Huds<strong>on</strong> Street<str<strong>on</strong>g>New</str<strong>on</strong>g> York, NY 10014www.penguinputnam.comCopyright © 1979,1989,1999 by Betty EdwardsAll rights reserved. This book, or parts <strong>the</strong>re<strong>of</strong>, may not be reproduced in any formwithout permissi<strong>on</strong>.Published simultaneously in CanadaLibrary <strong>of</strong> C<strong>on</strong>gress Cataloging-in-Publicati<strong>on</strong> DataEdwards, Betty.The new drawing <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> right side <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> brain / Betty Edwards.—Rev. and expanded ed.p. cm.Rev. and expanded ed. <strong>of</strong>: <str<strong>on</strong>g>Drawing</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> right side <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> brain.Includes bibliographical references.ISBN 0-87477-419-5 (hardcover). — ISBN 0-87477-424-1 (pbk.)1. <str<strong>on</strong>g>Drawing</str<strong>on</strong>g>—Technique. 2. Visual percepti<strong>on</strong>. 3. Cerebral dominance.I. Edwards, Betty. <str<strong>on</strong>g>Drawing</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> right side <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> brain. II. Title. III. Title:<str<strong>on</strong>g>Drawing</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> right side <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> brain.NC.730.E34 199999-35809 CIP741.2—dc2iCover drawing: Betty EdwardsInstructi<strong>on</strong>al drawings: Betty Edwards and Brian BomeislerDesign:Joe MolloyTypeset in M<strong>on</strong>otype Jans<strong>on</strong> by M<strong>on</strong>do Typo, Inc.Printed in <strong>the</strong> United States <strong>of</strong> America40 39 38 37 36 35 34 33This book is printed <strong>on</strong> acid-free paper. ®

To <strong>the</strong> memory <strong>of</strong> my fa<strong>the</strong>r,who sharpened my drawing pencilswith his pocketknifewhen I was a child

C<strong>on</strong>tentsPrefaceXIntroducti<strong>on</strong>XVII1. <str<strong>on</strong>g>Drawing</str<strong>on</strong>g> and <strong>the</strong> Art <strong>of</strong> Bicycle RidingI2: The <str<strong>on</strong>g>Drawing</str<strong>on</strong>g> Exercises: One Step at a TimeII3. Your <strong>Brain</strong>: The <strong>Right</strong> and Left <strong>of</strong> It274. Crossing Over: Experiencing <strong>the</strong> Shift from Left to <strong>Right</strong>495. <str<strong>on</strong>g>Drawing</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> Memories: Your History as an Artist676. Getting Around Your Symbol System: Meeting Edges and C<strong>on</strong>tours877. Perceiving <strong>the</strong> Shape <strong>of</strong> a Space: The Positive Aspects <strong>of</strong> Negative Space115

8. Relati<strong>on</strong>ships in a <str<strong>on</strong>g>New</str<strong>on</strong>g> Mode: Putting Sighting in Perspective1379. Facing Forward: Portrait <str<strong>on</strong>g>Drawing</str<strong>on</strong>g> with Ease16110. The Value <strong>of</strong> Logical Lights and Shadows19311. <str<strong>on</strong>g>Drawing</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> Beauty <strong>of</strong> Color22912. The Zen <strong>of</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Drawing</str<strong>on</strong>g>: <str<strong>on</strong>g>Drawing</str<strong>on</strong>g> Out <strong>the</strong> Artist Within247Afterword: Is Beautiful Handwriting a Lost Art?253Postscript267Glossary275Bibliography279 .Index 283

PrefaceTwenty years have passed since <strong>the</strong> first publicati<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Drawing</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong><strong>the</strong> <strong>Right</strong> <strong>Side</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Brain</strong> in July 1979. Ten years ago, in 1989,I revised <strong>the</strong> book and published a sec<strong>on</strong>d editi<strong>on</strong>, bringing it upto date with what I had learned during that decade. Now, in 1999,I am revising <strong>the</strong> book <strong>on</strong>e more time. This latest revisi<strong>on</strong> representsa culminati<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong> my lifel<strong>on</strong>g engrossment in drawing as aquintessentially human activity.How I came to write this bookOver <strong>the</strong> years, many people have asked me how I came to writethis book. As <strong>of</strong>ten happens, it was <strong>the</strong> result <strong>of</strong> numerous chanceevents and seemingly random choices. First, my training andbackground were in fine arts—drawing and painting, not in arteducati<strong>on</strong>. This point is important, I think, because I came toteaching with a different set <strong>of</strong> expectati<strong>on</strong>s.After a modest try at living <strong>the</strong> artist's life, I began giving privateless<strong>on</strong>s in painting and drawing in my studio to help pay <strong>the</strong>bills. Then, needing a steadier source <strong>of</strong> income, I returned toUCLA to earn a teaching credential. On completi<strong>on</strong>, I beganteaching at Venice High School in Los Angeles. It was a marvelousjob. We had a small art department <strong>of</strong> five teachers andlively, bright, challenging, and difficult students. Art was <strong>the</strong>irfavorite subject, it seemed, and our students <strong>of</strong>ten swept up manyawards in <strong>the</strong> <strong>the</strong>n-popular citywide art c<strong>on</strong>tests.At Venice High, we tried to reach students in <strong>the</strong>ir first year,quickly teach <strong>the</strong>m to draw well, and <strong>the</strong>n train <strong>the</strong>m up, almostlike athletes, for <strong>the</strong> art competiti<strong>on</strong>s during <strong>the</strong>ir junior andsenior years. (I now have serious reservati<strong>on</strong>s about student c<strong>on</strong>-XPREFACE

tests, but at <strong>the</strong> time <strong>the</strong>y provided great motivati<strong>on</strong> and, perhapsbecause <strong>the</strong>re were so many winners, apparently caused littleharm.)Those five years at Venice High started my puzzlement aboutdrawing. As <strong>the</strong> newest teacher <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> group, I was assigned <strong>the</strong>job <strong>of</strong> bringing <strong>the</strong> students up to speed in drawing. Unlike manyart educators who believe that ability to draw well is dependent<strong>on</strong> inborn talent, I expected that all <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> students would learn todraw. I was ast<strong>on</strong>ished by how difficult <strong>the</strong>y found drawing, nomatter how hard I tried to teach <strong>the</strong>m and <strong>the</strong>y tried to learn.I would <strong>of</strong>ten ask myself, "Why is it that <strong>the</strong>se students, whoI know are learning o<strong>the</strong>r skills, have so much trouble learning todraw something that is right in fr<strong>on</strong>t <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir eyes?" I would sometimesquiz <strong>the</strong>m, asking a student who was having difficulty drawinga still-life setup, "Can you see in <strong>the</strong> still-life here <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> tablethat <strong>the</strong> orange is in fr<strong>on</strong>t <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> vase?" "Yes," replied <strong>the</strong> student,"I see that." "Well," I said, "in your drawing, you have <strong>the</strong> orangeand <strong>the</strong> vase occupying <strong>the</strong> same space." The student answered,"Yes, I know. I didn't know how to draw that." "Well," I would saycarefully, "you look at <strong>the</strong> still-life and you draw it as you see it.""I was looking at it," <strong>the</strong> student replied. "I just didn't know howto draw that." "Well," I would say, voice rising, "you just look atit..." The resp<strong>on</strong>se would come, "I am looking at it," and so <strong>on</strong>.Ano<strong>the</strong>r puzzlement was that students <strong>of</strong>ten seemed to "get"how to draw suddenly ra<strong>the</strong>r than acquiring skills gradually.Again, I questi<strong>on</strong>ed <strong>the</strong>m: "How come you can draw this weekwhen you couldn't draw last week?" Often <strong>the</strong> reply would be, "Id<strong>on</strong>'t know. I'm just seeing things differently." "In what way differently?"I would ask. "I can't say—just differently." I would pursue<strong>the</strong> point, urging students to put it into words, without success.Usually students ended by saying, "I just can't describe it."In frustrati<strong>on</strong>, I began to observe myself: What was I doingwhen I was drawing? Some things quickly showed up—that Icouldn't talk and draw at <strong>the</strong> same time, for example, and thatI lost track <strong>of</strong> time while drawing. My puzzlement c<strong>on</strong>tinued.PREFACEXI

One day, <strong>on</strong> impulse, I asked <strong>the</strong> students to copy a Picassodrawing upside down. That small experiment, more than anythingelse I had tried, showed that something very different isgoing <strong>on</strong> during <strong>the</strong> act <strong>of</strong> drawing. To my surprise, and to <strong>the</strong>students' surprise, <strong>the</strong> finished drawings were so extremely welld<strong>on</strong>e that I asked <strong>the</strong> class, "How come you can draw upsidedown when you can't draw right-side up?" The studentsresp<strong>on</strong>ded, "Upside down, we didn't know what we were drawing."This was <strong>the</strong> greatest puzzlement <strong>of</strong> all and left me simplybaffled.During <strong>the</strong> following year, 1968, first reports <strong>of</strong> psychobiologistRoger W. Sperry's research <strong>on</strong> human brain-hemispherefuncti<strong>on</strong>s, for which he later received a Nobel Prize, appeared in<strong>the</strong> press. Reading Sperry's work caused in me something <strong>of</strong> anAh-ha! experience. His stunning finding, that <strong>the</strong> human brainuses two fundamentally different modes <strong>of</strong> thinking, <strong>on</strong>e verbal,analytic, and sequential and <strong>on</strong>e visual, perceptual, and simultaneous,seemed to cast light <strong>on</strong> my questi<strong>on</strong>s about drawing. Theidea that <strong>on</strong>e is shifting to a different-from-usual way <strong>of</strong> thinking/seeingfitted my own experience <strong>of</strong> drawing and illuminatedmy observati<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong> my students.Avidly, I read everything I could find about Sperry's work anddid my best to explain to my students its possible relati<strong>on</strong>ship todrawing. They too became interested in <strong>the</strong> problems <strong>of</strong> drawingand so<strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong>y were achieving great advances in <strong>the</strong>ir drawingskills.I was working <strong>on</strong> my master's degree in Art at <strong>the</strong> time andrealized that if I wanted to seriously search for an educati<strong>on</strong>alapplicati<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong> Sperry's work in <strong>the</strong> field <strong>of</strong> drawing, I would needfur<strong>the</strong>r study. Even though by that time I was teaching full time atLos Angeles Trade Technical College, I decided to return yetagain to UCLA for a doctoral degree. For <strong>the</strong> following threeyears, I attended evening classes that combined <strong>the</strong> fields <strong>of</strong> art,psychology, and educati<strong>on</strong>. The subject <strong>of</strong> my doctoral dissertati<strong>on</strong>was "Perceptual Skills in <str<strong>on</strong>g>Drawing</str<strong>on</strong>g>," using upside-downdrawing as an experimental variable. After receiving my doctoraldegree in 1976, I began teaching drawing in <strong>the</strong> art department otXIIPREFACE

California State University, L<strong>on</strong>g Beach. I needed a drawing texthookthat included Sperry's research. During <strong>the</strong> next three yearsI wrote <str<strong>on</strong>g>Drawing</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Right</strong> <strong>Side</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Brain</strong>.Since <strong>the</strong> book was first published in 1979, <strong>the</strong> ideas I expressedabout learning to draw have become surprisingly widespread,much to my amazement and delight. I feel h<strong>on</strong>ored by <strong>the</strong> manyforeign language translati<strong>on</strong>s <strong>of</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Drawing</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Right</strong> <strong>Side</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><strong>Brain</strong>. Even more surprising, individuals and groups working infields not remotely c<strong>on</strong>nected with drawing have found ways touse <strong>the</strong> ideas in my book. A few examples will indicate <strong>the</strong> diversity:nursing schools, drama workshops, corporate training seminars,sports-coaching schools, real-estate marketing associati<strong>on</strong>s,psychologists, counselors <strong>of</strong> delinquent youths, writers, hair stylists,even a school for training private investigators. College anduniversity art teachers across <strong>the</strong> nati<strong>on</strong> also have incorporatedmany <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> techniques into <strong>the</strong>ir teaching repertoires.Public-school teachers are also using my book. After twentyfiveyears <strong>of</strong> budget cuts in schools' arts programs, I am happy toreport that state departments <strong>of</strong> educati<strong>on</strong> and public schoolboards <strong>of</strong> educati<strong>on</strong> are starting to turn to <strong>the</strong> arts as <strong>on</strong>e way tohelp repair our failing educati<strong>on</strong>al systems. Educati<strong>on</strong>al administrators,however, tend to be ambivalent about <strong>the</strong> purpose <strong>of</strong>including <strong>the</strong> arts, <strong>of</strong>ten still relegating arts educati<strong>on</strong> to "enrichment."This term's hidden meaning is "valuable but not essential."My view, in c<strong>on</strong>trast, is that <strong>the</strong> arts are essential for trainingspecific, visual, perceptual ways <strong>of</strong> thinking, just as <strong>the</strong> "3 R's" areessential for training specific, verbal, numerical, analytical ways<strong>of</strong> thinking. I believe that both thinking modes—<strong>on</strong>e to comprehend<strong>the</strong> details and <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r to "see" <strong>the</strong> whole picture, forexample, are vital for critical-thinking skills, extrapolati<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong>meaning, and problem solving.To help public-school administrators see <strong>the</strong> utility <strong>of</strong> artseducati<strong>on</strong>, I believe we must find new ways to teach students howto transfer skills learned through <strong>the</strong> arts to academic subjectsand problem solving. Transfer <strong>of</strong> learning is traditi<strong>on</strong>allyregarded as a most difficult kind <strong>of</strong> instructi<strong>on</strong> and, unfortunately,transfer is <strong>of</strong>ten left to chance. Teachers hope that students willSUGGESTED DESIGNFOR U.S. CAPITOL3. WORKINC DRAWING FROMWHICH THE ORIGINALPHONOCRAPH WAS BUILTIn <strong>the</strong> history <strong>of</strong> inventi<strong>on</strong>s, manycreative ideas began with smallsketches. The examples above areby Galileo, Jeffers<strong>on</strong>, Faraday, andEdis<strong>on</strong>.Henning Nelms, Thinking With aPencil, <str<strong>on</strong>g>New</str<strong>on</strong>g> York: Ten Speed Press,1981, p. xiv.PREFACEXIII

"get" <strong>the</strong> c<strong>on</strong>necti<strong>on</strong>, say, between learning to draw and "seeing"soluti<strong>on</strong>s to problems, or between learning English grammar andlogical, sequential thinking.Corporate training seminars"Analog" drawings are purelyexpressive drawings, with no namableobjects depicted, using <strong>on</strong>ly <strong>the</strong>expressive quality <strong>of</strong> line—or lines.Unexpectedly, pers<strong>on</strong>s untrained inart are able to use this language—that is, produce expressive drawings—andare also able to read <strong>the</strong>drawings for meaning. The drawingless<strong>on</strong>s <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> seminar's first segmentare used mainly to increaseartistic self-c<strong>on</strong>fidence and c<strong>on</strong>fidencein <strong>the</strong> efficacy <strong>of</strong> analogdrawing.My work with various corporati<strong>on</strong>s represents, I believe, <strong>on</strong>easpect <strong>of</strong> transfer <strong>of</strong> learning, in this instance, from drawing skillsto a specific kind <strong>of</strong> problem solving sought by corporate executives.Depending <strong>on</strong> how much corporate time is available, atypical seminar takes three days: a day and a half focused <strong>on</strong>developing drawing skills and <strong>the</strong> remaining time devoted tousing drawing for problem solving.Groups vary in size but most <strong>of</strong>ten number about twenty-five.Problems can be very specific ("What is_________________?"—a specific chemical problem that had troubled a particular companyfor several years) or very general ("What is our relati<strong>on</strong>shipwith our customers?") or something in between specific and general("How can members <strong>of</strong> our special unit work toge<strong>the</strong>r moreproductively?").The first day and a half <strong>of</strong> drawing exercises includes <strong>the</strong>less<strong>on</strong>s in this book through <strong>the</strong> drawing <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> hand. The tw<strong>of</strong>oldobjective <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> drawing less<strong>on</strong>s is to present <strong>the</strong> five perceptualstrategies emphasized in <strong>the</strong> book and to dem<strong>on</strong>strate eachparticipant's potential artistic capabilities, given effective instructi<strong>on</strong>.The problem-solving segment begins with exercises in usingdrawing to think with. These exercises, called analog drawings,are described in my book <str<strong>on</strong>g>Drawing</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> Artist Within. Participantsuse <strong>the</strong> so-called "language <strong>of</strong> line," first to draw out <strong>the</strong> problemand <strong>the</strong>n to make visible possible soluti<strong>on</strong>s. These expressivedrawings become <strong>the</strong> vehicle for group discussi<strong>on</strong> and analysis,guided, but not led, by me. Participants use <strong>the</strong> c<strong>on</strong>cepts <strong>of</strong> edges(boundaries), negative spaces (<strong>of</strong>ten called "white spaces" in businessparlance), relati<strong>on</strong>ships (parts <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> problem viewed proporti<strong>on</strong>allyand "in perspective"), lights and shadows (extrapolati<strong>on</strong>from <strong>the</strong> known to <strong>the</strong> as-yet unknown), and <strong>the</strong> gestaltXIVPREFACE

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> problem (how <strong>the</strong> parts fit—or d<strong>on</strong>'t fit—toge<strong>the</strong>r).The problem-solving segment c<strong>on</strong>cludes with an extendedsmall drawing <strong>of</strong> an object, different for each participant, whichhas been chosen as somehow related to <strong>the</strong> problem at hand. Thisdrawing, combining perceptual skills with problem solving,evokes an extended shift to an alternate mode <strong>of</strong> thinking which Ihave termed "R-mode," during which <strong>the</strong> participant focuses <strong>on</strong><strong>the</strong> problem under discussi<strong>on</strong> while also c<strong>on</strong>centrating <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong>drawing. The group <strong>the</strong>n explores insights derived from thisprocess.The results <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> seminars have been sometimes startling,sometimes almost amusing in terms <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> obviousness <strong>of</strong> engenderedsoluti<strong>on</strong>s. An example <strong>of</strong> a startling result was a surprisingrevelati<strong>on</strong> experienced by <strong>the</strong> group working <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> chemicalproblem. It turned out that <strong>the</strong> group had so enjoyed <strong>the</strong>ir specialstatus and favored positi<strong>on</strong> and <strong>the</strong>y were so intrigued by <strong>the</strong> fascinatingproblem that <strong>the</strong>y were in no hurry to solve it. Also, solving<strong>the</strong> problem would mean breaking up <strong>the</strong> group andreturning to more humdrum work. All <strong>of</strong> this showed up clearlyin <strong>the</strong>ir drawings. The curious thing was that <strong>the</strong> group leaderexclaimed, "I thought that might be what was going <strong>on</strong>, but I justdidn't believe it!" The soluti<strong>on</strong>? The group realized that <strong>the</strong>yneeded—and welcomed—a serious deadline and assurance thato<strong>the</strong>r, equally interesting problems awaited <strong>the</strong>m.Ano<strong>the</strong>r surprising result came in resp<strong>on</strong>se to <strong>the</strong> questi<strong>on</strong>about customer relati<strong>on</strong>s. Participants' drawings in that seminarwere c<strong>on</strong>sistently complex and detailed. Nearly every drawingrepresented customers as small objects floating in large emptyspaces. Areas <strong>of</strong> great complexity excluded <strong>the</strong>se small objects.The ensuing discussi<strong>on</strong> clarified <strong>the</strong> group's (unc<strong>on</strong>scious) indifferencetoward and inattenti<strong>on</strong> to customers. That raised o<strong>the</strong>rquesti<strong>on</strong>s: What was in all <strong>of</strong> that empty negative space, and howcould <strong>the</strong> complex areas (identified in discussi<strong>on</strong> as aspects <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>work that were more interesting to <strong>the</strong> group) make c<strong>on</strong>necti<strong>on</strong>with customer c<strong>on</strong>cerns? This group planned to explore <strong>the</strong>problem fur<strong>the</strong>r.PREFACExv

Krishnamurti: "So where doessilence begin? Does it begin whenthought ends? Have you ever triedto end thought?"Questi<strong>on</strong>er: "How do you do it?"Krishnamurti: "I d<strong>on</strong>'t know, buthave you ever tried it? First <strong>of</strong> all,who is <strong>the</strong> entity who is trying tostop thought?"Questi<strong>on</strong>er: "The thinker."Krishnamurti: "It's ano<strong>the</strong>r thought,isn't it? Thought is trying to stopitself, so <strong>the</strong>re is a battle between<strong>the</strong> thinker and <strong>the</strong> thought....Thought says, 'I must stop thinkingbecause <strong>the</strong>n I shall experience amarvelous state.'... One thought istrying to suppress ano<strong>the</strong>r thought,so <strong>the</strong>re is c<strong>on</strong>flict. When I see thisas a fact, see it totally, understandit completely, have an insight intoit... <strong>the</strong>n <strong>the</strong> mind is quiet. Thiscomes about naturally and easilywhen <strong>the</strong> mind is quiet to watch, tolook, to see."—J. KrishnamurtiYou Are <strong>the</strong> World, 1972The group seeking more productive ways <strong>of</strong> workingtoge<strong>the</strong>r came to a c<strong>on</strong>clusi<strong>on</strong> that was so obvious <strong>the</strong> groupactually laughed about it. Their c<strong>on</strong>clusi<strong>on</strong> was that <strong>the</strong>yneeded to improve communicati<strong>on</strong> within <strong>the</strong> group. Memberswere nearly all scientists holding advanced degrees in chemistryand physics. Apparently, each pers<strong>on</strong> had a specificassignment for <strong>on</strong>e part <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> whole task, but <strong>the</strong>y worked indifferent buildings with different groups <strong>of</strong> associates and <strong>on</strong>individual time schedules. For more than twenty-five years<strong>the</strong>y had never met toge<strong>the</strong>r as a group until we held ourthree-day seminar.I hope <strong>the</strong>se examples give-at least some flavor <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> corporateseminars. Participants, <strong>of</strong> course, are highly educated,successful pr<strong>of</strong>essi<strong>on</strong>als. Working as I do with a different way <strong>of</strong>thinking, <strong>the</strong> seminars seem to enable <strong>the</strong>se highly trainedpeople to see things differently. Because <strong>the</strong> participants <strong>the</strong>mselvesgenerate <strong>the</strong> drawings, <strong>the</strong>y provide real evidence torefer to. Thus, insights are hard to dismiss and <strong>the</strong> discussi<strong>on</strong>sstay very focused.I can <strong>on</strong>ly speculate why this process works effectively toget at informati<strong>on</strong> that is <strong>of</strong>ten hidden or ignored or "explainedaway" by <strong>the</strong> language mode <strong>of</strong> thinking. I think it's possiblethat <strong>the</strong> language system (L-mode, in my terminology) regardsdrawing—especially analog drawing—as unimportant, even asjust a form <strong>of</strong> doodling. Perhaps, L-mode drops out <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> task,putting its censoring functi<strong>on</strong> <strong>on</strong> hold. Apparently, what <strong>the</strong>pers<strong>on</strong> knows but doesn't know at a verbal, c<strong>on</strong>scious level<strong>the</strong>refore comes pouring out in <strong>the</strong> drawings. Traditi<strong>on</strong>al executives,<strong>of</strong> course, may regard this informati<strong>on</strong> as "s<strong>of</strong>t," butI suspect that <strong>the</strong>se unspoken reacti<strong>on</strong>s do have some effect <strong>on</strong><strong>the</strong> ultimate success and failure <strong>of</strong> corporati<strong>on</strong>s. Broadlyspeaking, a glimpse <strong>of</strong> underlying affective dynamics probablyhelps more than it hinders.XVIPREFACE

Introducti<strong>on</strong>The subject <strong>of</strong> how people learn to draw has never lost its charmand fascinati<strong>on</strong> for me. Just when I begin to think I have a grasp<strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> subject, a whole new vista or puzzlement opens up. Thisbook, <strong>the</strong>refore, is a work in progress, documenting my understandingat this time.<str<strong>on</strong>g>Drawing</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Right</strong> <strong>Side</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Brain</strong>, I believe, was <strong>on</strong>e <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>first practical educati<strong>on</strong>al applicati<strong>on</strong>s <strong>of</strong> Roger Sperry's pi<strong>on</strong>eeringinsight into <strong>the</strong> dual nature <strong>of</strong> human thinking—verbal, analyticthinking mainly located in <strong>the</strong> left hemisphere, and visual,perceptual thinking mainly located in <strong>the</strong> right hemisphere.Since 1979, many writers in o<strong>the</strong>r fields have proposed applicati<strong>on</strong>s<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> research, each in turn suggesting new ways toenhance both thinking modes, <strong>the</strong>reby increasing potential forpers<strong>on</strong>al growth.During <strong>the</strong> past ten years, my colleagues and I have polishedand expanded <strong>the</strong> techniques described in <strong>the</strong> original book. Wehave changed some procedures, added some, and deleted some.My main purpose in revising <strong>the</strong> book and presenting this thirdediti<strong>on</strong> is to bring <strong>the</strong> work up-to-date again for my readers.As you will see, much <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> original work is retained, havingwithstood <strong>the</strong> test <strong>of</strong> time. But <strong>on</strong>e important organizing principlewas missing in <strong>the</strong> original text, for <strong>the</strong> curious reas<strong>on</strong> thatI couldn't see it until after <strong>the</strong> book was published. I want toreemphasize it here, because it forms <strong>the</strong> overall structure withinwhich <strong>the</strong> reader can see how <strong>the</strong> parts <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> book fit toge<strong>the</strong>r t<strong>of</strong>orm a whole. This key principle is: <str<strong>on</strong>g>Drawing</str<strong>on</strong>g> is a global or"whole" skill requiring <strong>on</strong>ly a limited set <strong>of</strong> basic comp<strong>on</strong>ents.This insight came to me about six m<strong>on</strong>ths after <strong>the</strong> book waspublished, right in <strong>the</strong> middle <strong>of</strong> a sentence while teaching aINTRODUCTIONXVII

Please note that I am referring to<strong>the</strong> learning stage <strong>of</strong> basic realisticdrawing <strong>of</strong> a perceived image.There are many o<strong>the</strong>r kinds <strong>of</strong>drawing: abstracti<strong>on</strong>, n<strong>on</strong>objectivedrawing, imaginative drawing,mechanical drawing, and so forth.Also, drawing can be defined inmany o<strong>the</strong>r ways—by mediums,historic styles, or <strong>the</strong> artist's intent.group <strong>of</strong> students. It was <strong>the</strong> classic Ah-ha! experience, with <strong>the</strong>strange physical sensati<strong>on</strong>s <strong>of</strong> rapid heartbeat, caught breath, anda sense <strong>of</strong> joyful excitement at seeing everything fall into place. Ihad been reviewing with <strong>the</strong> students <strong>the</strong> set <strong>of</strong> skills described inmy book when it hit me that this was it, <strong>the</strong>re were no more, andthat <strong>the</strong> book had a hidden c<strong>on</strong>tent <strong>of</strong> which I had been unaware.I checked <strong>the</strong> insight with my colleagues and drawing experts.They agreed.Like o<strong>the</strong>r global skills—for example, reading, driving, skiing,and walking—drawing is made up <strong>of</strong> comp<strong>on</strong>ent skills thatbecome integrated into a whole skill. Once you have learned <strong>the</strong>comp<strong>on</strong>ents and have integrated <strong>the</strong>m, you can draw—just as<strong>on</strong>ce you have learned to read, you know how to read for life;<strong>on</strong>ce you have learned to walk, you know how to walk for life. Youd<strong>on</strong>'t have to go <strong>on</strong> forever adding additi<strong>on</strong>al basic skills. Progresstakes <strong>the</strong> form <strong>of</strong> practice, refinement <strong>of</strong> technique, and learningwhat to use <strong>the</strong> skills for.This was an exciting discovery because it meant that a pers<strong>on</strong>can learn to draw within a reas<strong>on</strong>ably short time. And, in fact, mycolleagues and I now teach a five-day seminar, f<strong>on</strong>dly known asour "Killer Class," which enables students to acquire <strong>the</strong> basiccomp<strong>on</strong>ent skills <strong>of</strong> realistic drawing in five days <strong>of</strong> intense learning.Five basic skills <strong>of</strong> drawingThe global skill <strong>of</strong> drawing a perceived object, pers<strong>on</strong>, landscape(something that you see "out <strong>the</strong>re") requires <strong>on</strong>ly five basic comp<strong>on</strong>entskills, no more. These skills are not drawing skills. Theyare perceptual skills, listed as follows:One:Two:<strong>the</strong> percepti<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong> edges<strong>the</strong> percepti<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong> spacesThree: <strong>the</strong> percepti<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong> relati<strong>on</strong>shipsFour: <strong>the</strong> percepti<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong> lights and shadowsFive:<strong>the</strong> percepti<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> whole, or gestaltXVIIIINTRODUCTION

I am aware, <strong>of</strong> course, that additi<strong>on</strong>al basic skills are requiredfor imaginative, expressive drawing leading to "Art with a capitalA." Of <strong>the</strong>se, I have found two and <strong>on</strong>ly two additi<strong>on</strong>al skills:drawing from memory and drawing from imaginati<strong>on</strong>. And <strong>the</strong>reremain, naturally, many techniques <strong>of</strong> drawing—many ways <strong>of</strong>manipulating drawing mediums and endless subject matter, forexample. But, to repeat, for skillful realistic drawing <strong>of</strong> <strong>on</strong>e's percepti<strong>on</strong>s,using pencil <strong>on</strong> paper, <strong>the</strong> five skills I will teach you inthis book provide <strong>the</strong> required perceptual training.Those five basic skills are <strong>the</strong> prerequisites for effective use <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong> two additi<strong>on</strong>al "advanced" skills, and <strong>the</strong> set <strong>of</strong> seven mayc<strong>on</strong>stitute <strong>the</strong> entire basic global skill <strong>of</strong> drawing. Many books <strong>on</strong>drawing actually focus mainly <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> two advanced skills. Therefore,after you complete <strong>the</strong> less<strong>on</strong>s in this book, you will findample instructi<strong>on</strong> available to c<strong>on</strong>tinue learning.I need to emphasize a fur<strong>the</strong>r point: Global or whole skills,such as reading, driving, and drawing, in time become automatic.As I menti<strong>on</strong>ed above, basic comp<strong>on</strong>ent skills become completelyintegrated into <strong>the</strong> smooth flow <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> global skill. But in acquiringany new global skill, <strong>the</strong> initial learning is <strong>of</strong>ten a struggle,first with each comp<strong>on</strong>ent skill, <strong>the</strong>n with <strong>the</strong> smooth integrati<strong>on</strong><strong>of</strong> comp<strong>on</strong>ents. Each <strong>of</strong> my students goes through this process,and so will you. As each new skill is learned, you will merge itwith those previously learned until, <strong>on</strong>e day, you are simplydrawing—just as, <strong>on</strong>e day, you found yourself simply drivingwithout thinking about how to do it. Later, <strong>on</strong>e almost forgetsabout having learned to read, learned to drive, learned to draw.In order to attain this smooth integrati<strong>on</strong> in drawing, all fivecomp<strong>on</strong>ent skills must be in place. I'm happy to say that <strong>the</strong> fifthskill, <strong>the</strong> percepti<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> whole, or gestalt, is nei<strong>the</strong>r taught norlearned but instead seems to emerge as a result <strong>of</strong> acquiring <strong>the</strong>o<strong>the</strong>r four skills. But <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> first four, n<strong>on</strong>e can be omitted, just as •learning how to brake or steer cannot be omitted when learningto drive.In <strong>the</strong> original book, I believe I explained sufficiently well <strong>the</strong>first two skills, <strong>the</strong> percepti<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong> edges and <strong>the</strong> percepti<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong>spaces. The importance <strong>of</strong> sighting (<strong>the</strong> third skill <strong>of</strong> perceivingThe global skill <strong>of</strong> drawingINTRODUCTIONXIX

elati<strong>on</strong>ships) however, needed greater emphasis and clearerexplanati<strong>on</strong>, because students <strong>of</strong>ten tend to give up too quickly<strong>on</strong> this complicated skill. And <strong>the</strong> fourth skill, <strong>the</strong> percepti<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong>lights and shadows, also needed expanding. Most <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> c<strong>on</strong>tentchanges for this new editi<strong>on</strong>, <strong>the</strong>refore, are in <strong>the</strong> last chapters."You have two brains: a left and aright. Modern brain scientists nowknow that your left brain is yourverbal and rati<strong>on</strong>al brain; it thinksserially and reduces its thoughts t<strong>on</strong>umbers, letters, and words....Your right brain is your n<strong>on</strong>-verbaland intuitive brain; it thinks in patterns,or pictures, composed <strong>of</strong>'whole things,' and does not comprehendreducti<strong>on</strong>s, ei<strong>the</strong>r numbers,letters, or words."From The Fabric <strong>of</strong> Mind, by <strong>the</strong>eminent scientist and neurosurge<strong>on</strong>Richard Bergland. <str<strong>on</strong>g>New</str<strong>on</strong>g> York:Viking Penguin, Inc., 1985, p. 1.A basic strategy for accessing R-modeIn this editi<strong>on</strong>, I again reiterate a basic strategy for gaining accessat c<strong>on</strong>scious level to R-mode, my term for <strong>the</strong> visual, perceptualmode <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> brain. I c<strong>on</strong>tinue to believe that this strategy is probablymy main c<strong>on</strong>tributi<strong>on</strong> to educati<strong>on</strong>al aspects <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> "righ<strong>the</strong>mispherestory" that began with Roger Sperry's celebratedscientific work. The strategy is stated as follows:In order to gain access to <strong>the</strong> subdominant visual, perceptualR-mode <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> brain, it is necessary to present <strong>the</strong> brain with a jobthat <strong>the</strong> verbal, analytic L-mode will turn down.For most <strong>of</strong> us, L-mode thinking seems easy, normal, andfamiliar (though perhaps not for many children and dyslexicindividuals). The perverse R-mode strategy, in c<strong>on</strong>trast, mayseem difficult and unfamiliar—even "<strong>of</strong>f-<strong>the</strong>-wall." It must belearned in oppositi<strong>on</strong> to <strong>the</strong> "natural" tendency <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> brain t<strong>of</strong>avor L-mode because, in general, language dominates. By learningto c<strong>on</strong>trol this tendency for specific tasks, <strong>on</strong>e gains access topowerful brain functi<strong>on</strong>s <strong>of</strong>ten obscured by language.All <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> exercises in this book, <strong>the</strong>refore, are based <strong>on</strong> twoorganizing principles and major aims. First, to teach <strong>the</strong> readerfive basic comp<strong>on</strong>ent skills <strong>of</strong> drawing and, sec<strong>on</strong>d, to providec<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong>s that facilitate making cognitive shifts to R-mode, <strong>the</strong>thinking/seeing mode specialized for drawing.In short, in <strong>the</strong> process <strong>of</strong> learning to draw, <strong>on</strong>e also learns toc<strong>on</strong>trol (at least to some degree) <strong>the</strong> mode by which <strong>on</strong>e's ownbrain handles informati<strong>on</strong>. Perhaps this explains in part why mybook appeals to individuals from such diverse fields. Intuitively,<strong>the</strong>y see <strong>the</strong> link to o<strong>the</strong>r activities and <strong>the</strong> possibility <strong>of</strong> seeingthings differently by learning to access R-mode at c<strong>on</strong>sciouslevel.xxINTRODUCTION

Color in drawingChapter Eleven, "<str<strong>on</strong>g>Drawing</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> Beauty <strong>of</strong> Color," was a newchapter in <strong>the</strong> 1989 editi<strong>on</strong>, written in resp<strong>on</strong>se to many requestsfrom my readers. The chapter focuses <strong>on</strong> using color in drawing—afine transiti<strong>on</strong>al step toward painting. Over <strong>the</strong> pastdecade, my teaching staff and I have developed a five-day intensivecourse <strong>on</strong> basic color <strong>the</strong>ory, a course that is still a "work inprogress." I am still using <strong>the</strong> c<strong>on</strong>cepts in <strong>the</strong> chapter <strong>on</strong> color, soI have not revised it for this editi<strong>on</strong>.I believe <strong>the</strong> logical progressi<strong>on</strong> for a pers<strong>on</strong> starting out inartistic expressi<strong>on</strong> should be as follows:From Line to Value to Color to PaintingFirst, a pers<strong>on</strong> learns <strong>the</strong> basic skills <strong>of</strong> drawing, which provideknowledge <strong>of</strong> line (learned through c<strong>on</strong>tour drawing <strong>of</strong>edges, spaces, and relati<strong>on</strong>ships) and knowledge <strong>of</strong> value (learnedthrough rendering lights and shadows). Skillful use <strong>of</strong> colorrequires first <strong>of</strong> all <strong>the</strong> ability to perceive color as value. This abilityis difficult, perhaps impossible, to acquire unless <strong>on</strong>e haslearned to perceive <strong>the</strong> relati<strong>on</strong>ships <strong>of</strong> lights and shadowsthrough drawing. I hope that my chapter introducing color indrawing will provide an effective bridge for those who want toprogress from drawing to painting.HandwritingFinally, I am retaining <strong>the</strong> brief secti<strong>on</strong> <strong>on</strong> handwriting. In manycultures, writing is regarded as an art form. Americans <strong>of</strong>tendeplore <strong>the</strong>ir handwriting but are at a loss as to how to improve it.Handwriting, however, is a form <strong>of</strong> drawing and can be improved.I regret to say that many California schools are still usinghandwriting-instructi<strong>on</strong>al methods that were failing in 1989 andare still failing today. My suggesti<strong>on</strong>s in this regard appear in <strong>the</strong>Afterword.INTRODUCTIONXXI

An empirical basis for my <strong>the</strong>oryThe underlying <strong>the</strong>ory <strong>of</strong> this revised editi<strong>on</strong> remains <strong>the</strong> same:to explain in basic terms <strong>the</strong> relati<strong>on</strong>ship <strong>of</strong> drawing to visual,perceptual brain processes and to provide methods <strong>of</strong> accessingand c<strong>on</strong>trolling <strong>the</strong>se processes. As a number <strong>of</strong> scientists havenoted, research <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> human brain is complicated by <strong>the</strong> factthat <strong>the</strong> brain is struggling to understand itself. This three-poundorgan is perhaps <strong>the</strong> <strong>on</strong>ly bit <strong>of</strong> matter in <strong>the</strong> universe—at least asfar as we know—that is observing itself, w<strong>on</strong>dering about itself,trying to analyze itself, and attempting to gain better c<strong>on</strong>trol <strong>of</strong>its own capabilities. This paradoxical situati<strong>on</strong> no doubt c<strong>on</strong>tributes—atleast in part—to <strong>the</strong> deep mysteries that still remain,despite rapidly expanding scientific knowledge about <strong>the</strong> brain.One questi<strong>on</strong> scientists are studying intensely is where <strong>the</strong>two major thinking modes are specifically located in <strong>the</strong> humanbrain and how <strong>the</strong> organizati<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong> modes can vary from individualto individual. While <strong>the</strong> so-called locati<strong>on</strong> c<strong>on</strong>troversy c<strong>on</strong>tinuesto engage scientists, al<strong>on</strong>g with myriad o<strong>the</strong>r areas <strong>of</strong> brainresearch, <strong>the</strong> existence in every brain <strong>of</strong> two fundamentally differentcognitive modes is no l<strong>on</strong>ger c<strong>on</strong>troversial. Corroboratingresearch since Sperry's original work is overwhelming. Moreover,even in <strong>the</strong> midst <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> argument about locati<strong>on</strong>, most scientistsagree that for a majority <strong>of</strong> individuals, informati<strong>on</strong>-processingbased primarily <strong>on</strong> linear, sequential data is mainly located in <strong>the</strong>left hemisphere, while global, perceptual data is mainlyprocessedin <strong>the</strong> right hemisphere.Clearly, for educators like myself, <strong>the</strong> precise locati<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong>se modes in <strong>the</strong> individual brain is not an important issue.What is important is that incoming informati<strong>on</strong> can be handled intwo fundamentally different ways and that <strong>the</strong> two modes canapparently work toge<strong>the</strong>r in a vast array <strong>of</strong> combinati<strong>on</strong>s. Since<strong>the</strong> late 1970s, I have used <strong>the</strong> terms L-mode and R-mode to try toavoid <strong>the</strong> locati<strong>on</strong> c<strong>on</strong>troversy. The terms are intended to differentiate<strong>the</strong> major modes <strong>of</strong> cogniti<strong>on</strong>, regardless <strong>of</strong> where <strong>the</strong>yare located in <strong>the</strong> individual brain.Over <strong>the</strong> past decade or so, a new interdisciplinary field <strong>of</strong>XXIIINTRODUCTION

ain-functi<strong>on</strong> study has become formally known as cognitiveneuroscience. In additi<strong>on</strong> to <strong>the</strong> traditi<strong>on</strong>al discipline <strong>of</strong> neurology,cognitive neuroscience encompasses study <strong>of</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r highercognitive processes such as language, memory, and percepti<strong>on</strong>.Computer scientists, linguists, neuroimaging scientists, cognitivepsychologists, and neurobiologists are all c<strong>on</strong>tributing to a growingunderstanding <strong>of</strong> how <strong>the</strong> human brain functi<strong>on</strong>s.Interest in "right brain, left brain" research has subsidedsomewhat am<strong>on</strong>g educators and <strong>the</strong> general public since RogerSperry first published his research findings. Never<strong>the</strong>less, <strong>the</strong> fact<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> pr<strong>of</strong>ound asymmetry <strong>of</strong> human brain functi<strong>on</strong>s remains,becoming ever more central, for example, am<strong>on</strong>g computer scientiststrying to emulate human mental processes. Facial recogniti<strong>on</strong>,a functi<strong>on</strong> ascribed to <strong>the</strong> right hemisphere, has been soughtfor decades and is still bey<strong>on</strong>d <strong>the</strong> capabilities <strong>of</strong> most computers.Ray Kurzweil, in his recent book The Age <strong>of</strong> Spiritual Machines(Viking, 1999) c<strong>on</strong>trasted human and computer capability in patternseeking (as in facial recogniti<strong>on</strong>) and sequential processing(as in calculati<strong>on</strong>):The human brain has about 100 billi<strong>on</strong> neur<strong>on</strong>s. With an estimatedaverage <strong>of</strong> <strong>on</strong>e thousand c<strong>on</strong>necti<strong>on</strong>s between each neur<strong>on</strong> and itsneighbors, we have about 100 trilli<strong>on</strong> c<strong>on</strong>necti<strong>on</strong>s, each capable <strong>of</strong> asimultaneous calculati<strong>on</strong>. That's ra<strong>the</strong>r massive parallel processing,and <strong>on</strong>e key to <strong>the</strong> strength <strong>of</strong> human thinking. A pr<strong>of</strong>ound weakness,however, is <strong>the</strong> excruciatingly slow speed <strong>of</strong> neural circuitry, <strong>on</strong>ly 200calculati<strong>on</strong>s per sec<strong>on</strong>d. For problems that benefit from massive parallelism,such a neural-net-based pattern recogniti<strong>on</strong>, <strong>the</strong> humanbrain does a great job. For problems that require extensive sequentialthinking, <strong>the</strong> human brain is <strong>on</strong>ly mediocre, (p. 103)In 1979, I proposed that drawing required a cognitive shift toR-mode, now postulated to be a massively parallel mode <strong>of</strong> processing,and away from L-mode, postulated to be a sequentialprocessing mode. I had no hard evidence to support my proposal,<strong>on</strong>ly my experience as an artist and a teacher. Over <strong>the</strong> years, Ihave been criticized occasi<strong>on</strong>ally by various neuroscientists foroverstepping <strong>the</strong> boundaries <strong>of</strong> my own field—though not byIn a c<strong>on</strong>versati<strong>on</strong> with his friendAndre Marchand, <strong>the</strong> French artistHenri Matisse described <strong>the</strong>process <strong>of</strong> passing percepti<strong>on</strong>sfrom <strong>on</strong>e way <strong>of</strong> looking toano<strong>the</strong>r:"Do you know that a man has <strong>on</strong>ly<strong>on</strong>e eye which sees and registerseverything; this eye, like a superbcamera which takes minute pictures,very sharp, tiny—and withthat picture man tells himself:'This time I know <strong>the</strong> reality <strong>of</strong>things,' and he is calm for amoment. Then, slowly superimposingitself <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> picture,ano<strong>the</strong>r eye makes its appearance,invisibly, which makes an entirelydifferent picture for him."Then our man no l<strong>on</strong>ger seesclearly, a struggle begins between<strong>the</strong> first and sec<strong>on</strong>d eye, <strong>the</strong> fight isfierce, finally <strong>the</strong> sec<strong>on</strong>d eye has<strong>the</strong> upper hand, takes over andthat's <strong>the</strong> end <strong>of</strong> it. Now it hascommand <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> situati<strong>on</strong>, <strong>the</strong> sec<strong>on</strong>deye can <strong>the</strong>n c<strong>on</strong>tinue its workal<strong>on</strong>e and elaborate its own pictureaccording to <strong>the</strong> laws <strong>of</strong> interiorvisi<strong>on</strong>. This very special eye isfound here," says Matisse, pointingto his brain.Marchand didn't menti<strong>on</strong> whichside <strong>of</strong> his brain Matisse pointedto.—J. FlamMatisse <strong>on</strong> Art, 1973INTRODUCTIONXXIII

A recent article in an educati<strong>on</strong>aljournal summarizes neuroscientists'objecti<strong>on</strong>s to "brain-basededucati<strong>on</strong>.""The fundamental problem with <strong>the</strong>right-brain versus left-brain claimsthat <strong>on</strong>e finds in educati<strong>on</strong>al literatureis that <strong>the</strong>y rely <strong>on</strong> our intuiti<strong>on</strong>sand folk <strong>the</strong>ories about <strong>the</strong>brain, ra<strong>the</strong>r than <strong>on</strong> what brainscience is actually able to tell us.Our folk <strong>the</strong>ories are too crudeand imprecise to have any scientificpredictive or instructi<strong>on</strong>alvalue. What modern brain scienceis telling us—and what brain-basededucators fail to appreciate—isthat it makes no scientific sense tomap gross, unanalyzed behaviorsand skills—reading, arithmetic,spatial reas<strong>on</strong>ing—<strong>on</strong>to <strong>on</strong>e brainhemisphere or ano<strong>the</strong>r."But <strong>the</strong> author also states:"Whe<strong>the</strong>r or not [brain-based]educati<strong>on</strong>al practices should beadopted must be determined <strong>on</strong><strong>the</strong> basis <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> impact <strong>on</strong> studentlearning."—John T. Bruer"In Search <strong>of</strong>...<strong>Brain</strong>-Based Educati<strong>on</strong>,"Phi Delta Kappan, May1999, p. 603Roger Sperry, who believed that my applicati<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong> his researchwas reas<strong>on</strong>able.What kept me working at my "folk" <strong>the</strong>ory (see <strong>the</strong> marginexcerpt) was that, when put into practice, <strong>the</strong> results were inspiring.Students <strong>of</strong> all ages made significant gains in drawing abilityand, by extensi<strong>on</strong>, in perceptual abilities, since drawing welldepends <strong>on</strong> seeing well. <str<strong>on</strong>g>Drawing</str<strong>on</strong>g> ability has always beenregarded as difficult to acquire, and has nearly always been additi<strong>on</strong>allyburdened by <strong>the</strong> noti<strong>on</strong> that it is an extraordinary, not anordinary, skill. If my method <strong>of</strong> teaching enables people to gain askill <strong>the</strong>y previously thought closed <strong>of</strong>f to <strong>the</strong>m, is it <strong>the</strong> neurologicalexplanati<strong>on</strong> that makes <strong>the</strong> method work, or is it somethingelse that I may not be aware <strong>of</strong>?I know that it is not simply my style <strong>of</strong> teaching that causes<strong>the</strong> method to work, since <strong>the</strong> hundreds <strong>of</strong> teachers who havereported equal success using my methods obviously have widelydiffering teaching styles. Would <strong>the</strong> exercises work without <strong>the</strong>neurological rati<strong>on</strong>ale? It's possible, but it would be very difficultto persuade people to accede to such unlikely exercises asupside-down drawing without some reas<strong>on</strong>able explanati<strong>on</strong>. Is it,<strong>the</strong>n, just <strong>the</strong> fact <strong>of</strong> giving people a rati<strong>on</strong>ale—that any rati<strong>on</strong>alewould do? Perhaps, but I have always been struck by <strong>the</strong> fact thatmy explanati<strong>on</strong> seems to make sense to people at a subjectivelevel. The <strong>the</strong>ory seems to fit <strong>the</strong>ir experience, and certainly <strong>the</strong>ideas derive from my own subjective experience with drawing.In each editi<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong> this book I have made <strong>the</strong> following statement:The <strong>the</strong>ory and methods presented in my book have provenempirically successful. In short, <strong>the</strong> method works, regardless <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong> extent to which future science may eventually determineexact locati<strong>on</strong> and c<strong>on</strong>firm <strong>the</strong> degree <strong>of</strong> separati<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong> brain functi<strong>on</strong>sin <strong>the</strong> two hemispheres.I hope that eventually scholars using traditi<strong>on</strong>al researchmethods will help answer <strong>the</strong> many questi<strong>on</strong>s I have myself aboutthis work. It does appear that recent research tends to corroboratemy basic ideas. For example, new findings <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> functi<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>huge bundle <strong>of</strong> nerve fibers c<strong>on</strong>necting <strong>the</strong> two hemispheres, <strong>the</strong>XXIVINTRODUCTION

corpus callosum, indicate that <strong>the</strong> corpus callosum can inhibit <strong>the</strong>passage <strong>of</strong> informati<strong>on</strong> from hemisphere to hemisphere when <strong>the</strong>task requires n<strong>on</strong>interference from <strong>on</strong>e or <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r hemisphere.Meanwhile, <strong>the</strong> work appears to bring a great deal <strong>of</strong> joy tomy students, whe<strong>the</strong>r or not we fully understand <strong>the</strong> underlyingprocess.A fur<strong>the</strong>r complicati<strong>on</strong>One fur<strong>the</strong>r complicati<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong> seeing needs menti<strong>on</strong>ing. The eyesga<strong>the</strong>r visual informati<strong>on</strong> by c<strong>on</strong>stantly scanning <strong>the</strong> envir<strong>on</strong>ment.But visual data from "out <strong>the</strong>re," ga<strong>the</strong>red by sight, is not<strong>the</strong> end <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> story. At least part, and perhaps much <strong>of</strong> what wesee is changed, interpreted, or c<strong>on</strong>ceptualized in ways thatdepend <strong>on</strong> a pers<strong>on</strong>'s training, mind-set, and past experiences. Wetend to see what we expect to see or what we decide we have seen.This expectati<strong>on</strong> or decisi<strong>on</strong>, however, <strong>of</strong>ten is not a c<strong>on</strong>sciousprocess. Instead, <strong>the</strong> brain frequently does <strong>the</strong> expecting and <strong>the</strong>deciding, without our c<strong>on</strong>scious awareness, and <strong>the</strong>n alters orrearranges—or even simply disregards—<strong>the</strong> raw data <strong>of</strong> visi<strong>on</strong>that hits <strong>the</strong> retina. Learning percepti<strong>on</strong> through drawing seemsto change this process and to allow a different, more direct kind <strong>of</strong>seeing. The brain's editing is somehow put <strong>on</strong> hold, <strong>the</strong>reby permitting<strong>on</strong>e to see more fully and perhaps more realistically.This experience is <strong>of</strong>ten moving and deeply affecting. Mystudents' most frequent comments after learning to draw are"Life seems so much richer now" and "I didn't realize how much<strong>the</strong>re is to see and how beautiful things are." This new way <strong>of</strong> seeingmay al<strong>on</strong>e be reas<strong>on</strong> enough to learn to draw."The artist is <strong>the</strong> c<strong>on</strong>fidant <strong>of</strong>nature. Flowers carry <strong>on</strong> dialogueswith him through <strong>the</strong> gracefulbending <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir stems and <strong>the</strong> harm<strong>on</strong>iouslytinted nuances <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>irblossoms. Every flower has a cordialword which nature directstowards him."— Auguste RodinINTRODUCTIONxxv

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Drawing</str<strong>on</strong>g> and<strong>the</strong> Art <strong>of</strong> BicycleRiding

DRAWING is A CURIOUS PROCESS, so intertwined with seeingthat <strong>the</strong> two can hardly be separated. Ability to drawdepends <strong>on</strong> ability to see <strong>the</strong> way an artist sees, and this kind <strong>of</strong>seeing can marvelously enrich your life.In many ways, teaching drawing is somewhat like teachingsome<strong>on</strong>e to ride a bicycle. It is very difficult to explain in words.In teaching some<strong>on</strong>e to ride a bicycle, you might say, "Well, youjust get <strong>on</strong>, push <strong>the</strong> pedals, balance yourself, and <strong>of</strong>f you'll go."Of course, that doesn't explain it at all, and you are likelyfinally to say, "I'll get <strong>on</strong> and show you how. Watch and see how Ido it."And so it is with drawing. Most art teachers and drawing textbookauthors exhort beginners to "change <strong>the</strong>ir ways <strong>of</strong> looking atthings" and to "learn how to see." The problem is that this differentway <strong>of</strong> seeing is as hard to explain as how to balance a bicycle,and <strong>the</strong> teacher <strong>of</strong>ten ends by saying, in effect, "Look at <strong>the</strong>seexamples and just keep trying. If you practice a lot, eventuallyyou may get it." While nearly every<strong>on</strong>e learns to ride a bicycle,many individuals never solve <strong>the</strong> problems <strong>of</strong> drawing. To put itmore precisely, most people never learn to see well enough todraw.Fig. I-I. Bellowing Bis<strong>on</strong>. Paleolithiccave painting from Altamira, Spain.<str<strong>on</strong>g>Drawing</str<strong>on</strong>g> by Brevil. Prehistoricartists were probably thought tohave magic powers.<str<strong>on</strong>g>Drawing</str<strong>on</strong>g> as a magical abilityBecause <strong>on</strong>ly a few individuals seem to possess <strong>the</strong> ability to seeand draw, artists are <strong>of</strong>ten regarded as pers<strong>on</strong>s with a rare Godgiventalent. To many people, <strong>the</strong> process <strong>of</strong> drawing seems mysteriousand somehow bey<strong>on</strong>d human understanding.Artists <strong>the</strong>mselves <strong>of</strong>ten do little to dispel <strong>the</strong> mystery. If youask an artist (that is, some<strong>on</strong>e who draws well as a result <strong>of</strong> ei<strong>the</strong>rl<strong>on</strong>g training or chance discovery <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> artist's way <strong>of</strong> seeing),"How do you draw something so that it looks real—say a portraitor a landscape?" <strong>the</strong> artist is likely to reply, "Well, I just have a giftfor it, I guess," or "I really d<strong>on</strong>'t know. I just start in and workthings out as I go al<strong>on</strong>g," or "Well, I just look at <strong>the</strong> pers<strong>on</strong> (or <strong>the</strong>landscape) and I draw what I see." The last reply seems like alogical and straightforward answer. Yet, <strong>on</strong> reflecti<strong>on</strong>, it clearly2THE NEW DRAWING ON THE RIGHT SIDE OF THE BRAIN

doesn't explain <strong>the</strong> process at all, and <strong>the</strong> sense that <strong>the</strong> skill <strong>of</strong>drawing is a vaguely magical ability persists (Figure I-I).While this attitude <strong>of</strong> w<strong>on</strong>der at artistic skill causes people toappreciate artists and <strong>the</strong>ir work, it does little to encourage individualsto try to learn to draw, and it doesn't help teachersexplain to students <strong>the</strong> process <strong>of</strong> drawing. Often, in fact, peopleeven feel that <strong>the</strong>y shouldn't take a drawing course because <strong>the</strong>yd<strong>on</strong>'t know already how to draw. This is like deciding that youshouldn't take a French class because you d<strong>on</strong>'t already speakFrench, or that you shouldn't sign up for a course in carpentrybecause you d<strong>on</strong>'t know how to build a house.<str<strong>on</strong>g>Drawing</str<strong>on</strong>g> as a learnable, teachable skillYou will so<strong>on</strong> discover that drawing is a skill that can be learnedby every normal pers<strong>on</strong> with average eyesight and average eyehandcoordinati<strong>on</strong>—with sufficient ability, for example, to threada needle or catch a baseball. C<strong>on</strong>trary to popular opini<strong>on</strong>, manualskill is not a primary factor in drawing. If your handwriting isreadable, or if you can print legibly, you have ample dexterity todraw well.We need say no more here about hands, but about eyes wecannot say enough. Learning to draw is more than learning <strong>the</strong>skill itself; by studying this book you will learn how to see. That is,you will learn how to process visual informati<strong>on</strong> in <strong>the</strong> specialway used by artists. That way is differentirom <strong>the</strong> way you usuallyprocess visual informati<strong>on</strong> and seems to require that you use yourbrain in a different way than you ordinarily use it.You will be learning, <strong>the</strong>refore, something about how yourbrain handles visual informati<strong>on</strong>. Recent research has begun tothrow new scientific light <strong>on</strong> that marvel <strong>of</strong> capability and complexity,<strong>the</strong> human brain. And <strong>on</strong>e <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> things we are learning ishow <strong>the</strong> special properties <strong>of</strong> our brains enable us to draw pictures<strong>of</strong> our percepti<strong>on</strong>s.Roger N. Shepard, pr<strong>of</strong>essor <strong>of</strong>psychology at Stanford University,recently described his pers<strong>on</strong>almode <strong>of</strong> creative thought duringwhich research ideas emerged inhis mind as unverbalized, essentiallycomplete, l<strong>on</strong>g-sought soluti<strong>on</strong>sto problems."That in all <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se sudden illuminati<strong>on</strong>smy ideas took shape in aprimarily visual-spatial form without,so far as I can introspect, anyverbal interventi<strong>on</strong> is in accordancewith what has always beenmy preferred mode <strong>of</strong> thinking....Many <strong>of</strong> my happiest hours havesince childhood been spentabsorbed in drawing, in tinkering,or in exercises <strong>of</strong> purely mentalvisualizati<strong>on</strong>."— Roger N . ShepardVisual Learning, Thinking,and Communicati<strong>on</strong>, 1978"Learning to draw is really amatter <strong>of</strong> learning to see—to seecorrectly—and that means a gooddeal more than merely lookingwith <strong>the</strong> eye."— Kim<strong>on</strong> NicolaidesThe Natural Way to Draw,1941DRAWING AND THE ART OF BICYCLE RIDING 3

Gertrude Stein asked <strong>the</strong> Frenchartist Henri Matisse whe<strong>the</strong>r, wheneating a tomato, he looked at it <strong>the</strong>way an artist would. Matissereplied:"No, when I eat a tomato I look at it<strong>the</strong> way any<strong>on</strong>e else would. Butwhen I paint a tomato, <strong>the</strong>n I see itdifferently."— Gertrude SteinPicasso, 1938"The painter draws with his eyes,not with his hands. Whatever hesees, if he sees it clear, he can putdown. The putting <strong>of</strong> it downrequires, perhaps, much care andlabor, but no more muscular agilitythan it takes for him to write hisname. Seeing clear is <strong>the</strong> importantthing."— Maurice GrosserThe Painter's Eye, 1951"It is in order to really see, to seeever deeper, ever more intensely,hence to be fully aware and alive,that I draw what <strong>the</strong> Chinese call'The Ten Thousand Things'around me. <str<strong>on</strong>g>Drawing</str<strong>on</strong>g> is <strong>the</strong> disciplineby which I c<strong>on</strong>stantly rediscover<strong>the</strong> world."I have learned that what I have notdrawn, I have never really seen,and that when I start drawing anordinary thing, I realize how extraordinaryit is, sheer miracle."— Frederick FranckThe Zen <strong>of</strong> Seeing, 1973<str<strong>on</strong>g>Drawing</str<strong>on</strong>g> and seeingThe magical mystery <strong>of</strong> drawing ability seems to be, in part atleast, an ability to make a shift in brain state to a different mode <strong>of</strong>seeing/perceiving. When you see in <strong>the</strong> special way in which experiencedartists see, <strong>the</strong>n you can draw. This is not to say that <strong>the</strong> drawings<strong>of</strong> great artists such as Le<strong>on</strong>ardo da Vinci or Rembrandt arenot still w<strong>on</strong>drous because we may know something about <strong>the</strong>cerebral process that went into <strong>the</strong>ir creati<strong>on</strong>. Indeed, scientificresearch makes master drawings seem even more remarkablebecause <strong>the</strong>y seem to cause a viewer to shift to <strong>the</strong> artist's mode <strong>of</strong>perceiving. But <strong>the</strong> basic skill <strong>of</strong> drawing is also accessible toevery<strong>on</strong>e who can learn to make <strong>the</strong> shift to <strong>the</strong> artist's mode andsee in <strong>the</strong> artist's way.The artist's way <strong>of</strong> seeing: A tw<strong>of</strong>old process<str<strong>on</strong>g>Drawing</str<strong>on</strong>g> is not really very difficult. Seeing is <strong>the</strong> problem, or, tobe more specific, shifting to a particular way <strong>of</strong> seeing. You maynot believe me at this moment. You may feel that you are seeingthings just fine and that it's <strong>the</strong> drawing that is hard. But <strong>the</strong> oppositeis true, and <strong>the</strong> exercises in this book are designed to help youmake <strong>the</strong> mental shift and gain a tw<strong>of</strong>old advantage. First, to openaccess by c<strong>on</strong>scious voliti<strong>on</strong> to <strong>the</strong> visual, perceptual mode <strong>of</strong> thinkingin order to experience a focus in your awareness, and sec<strong>on</strong>d,to see things in a different way. Both will enable you to draw well.Many artists have spoken <strong>of</strong> seeing things differently whiledrawing and have <strong>of</strong>ten menti<strong>on</strong>ed that drawing puts <strong>the</strong>m into asomewhat altered state <strong>of</strong> awareness. In that different subjectivestate, artists speak <strong>of</strong> feeling transported, "at <strong>on</strong>e with <strong>the</strong> work,"able to grasp relati<strong>on</strong>ships that <strong>the</strong>y ordinarily cannot grasp.Awareness <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> passage <strong>of</strong> time fades away and words recedefrom c<strong>on</strong>sciousness. Artists say that <strong>the</strong>y feel alert and aware yetare relaxed and free <strong>of</strong> anxiety, experiencing a pleasurable,almost mystical activati<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> mind.4THE NEW DRAWING ON THE RIGHT SIDE OF THE BRAIN

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Drawing</str<strong>on</strong>g> attenti<strong>on</strong> to states <strong>of</strong> c<strong>on</strong>sciousnessThe slightly altered c<strong>on</strong>sciousness state <strong>of</strong> feeling transported,which most artists experience while drawing, painting, sculpting,or doing any kind <strong>of</strong> art work, is a state probably not altoge<strong>the</strong>runfamiliar to you. You may have observed in yourself slight shiftsin your state <strong>of</strong> c<strong>on</strong>sciousness while engaged in much more ordinaryactivities than artwork.For example, most people are aware that <strong>the</strong>y occasi<strong>on</strong>allyslip from ordinary waking c<strong>on</strong>sciousness into <strong>the</strong> slightly alteredstate <strong>of</strong> daydreaming. As ano<strong>the</strong>r example, people <strong>of</strong>ten say thatreading takes <strong>the</strong>m "out <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>mselves." And o<strong>the</strong>r kinds <strong>of</strong> activitieswhich apparently produce a shift in c<strong>on</strong>sciousness state aremeditati<strong>on</strong>, jogging, needlework, typing, listening to music, and,<strong>of</strong> course, drawing itself.Also, I believe that driving <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> freeway probably induces aslightly different subjective state that is similar to <strong>the</strong> drawingstate. After all, in freeway driving we deal with visual images,keeping track <strong>of</strong> relati<strong>on</strong>al, spatial informati<strong>on</strong>, sensing complexcomp<strong>on</strong>ents <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> overall traffic c<strong>on</strong>figurati<strong>on</strong>. Many people findthat <strong>the</strong>y do a lot <strong>of</strong> creative thinking while driving, <strong>of</strong>ten losingtrack <strong>of</strong> time and experiencing a pleasurable sense <strong>of</strong> freedomfrom anxiety. These mental operati<strong>on</strong>s may activate <strong>the</strong> sameparts <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> brain used in drawing. Of course, if driving c<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong>sare difficult, if we are late or if some<strong>on</strong>e sharing <strong>the</strong> ridetalks with us, <strong>the</strong> shift to <strong>the</strong> alternative state doesn't occur. Thereas<strong>on</strong>s for this we'll take up in Chapter Three.The key to learning to draw, <strong>the</strong>refore, is to set up c<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong>sthat cause you to make a mental shift to a different mode <strong>of</strong> informati<strong>on</strong>processing—<strong>the</strong> slightly altered state <strong>of</strong> c<strong>on</strong>sciousness—that enables you to see well. In this drawing mode, you will beable to draw your percepti<strong>on</strong>s even though you may never havestudied drawing. Once <strong>the</strong> drawing mode is familiar to you, youwill be able to c<strong>on</strong>sciously c<strong>on</strong>trol <strong>the</strong> mental shift."If a certain kind <strong>of</strong> activity, such aspainting, becomes <strong>the</strong> habitualmode <strong>of</strong> expressi<strong>on</strong>, it may followthat taking up <strong>the</strong> painting materialsand beginning work with <strong>the</strong>mwill act suggestively and sopresently evoke a flight into <strong>the</strong>higher state."— Robert HenriThe Art Spirit, 1923DRAWING AND THE ART OF BICYCLE RIDING5

My students <strong>of</strong>ten report thatlearning to draw makes <strong>the</strong>m feelmore creative. Obviously, manyroads lead to creative endeavor:<str<strong>on</strong>g>Drawing</str<strong>on</strong>g> is <strong>on</strong>ly <strong>on</strong>e route. HowardGardner, Harvard pr<strong>of</strong>essor <strong>of</strong>psychology and educati<strong>on</strong>, refersto this linkage:"By a curious twist, <strong>the</strong> words artand creativity have become closelylinked in our society."From Gardner's book CreatingMinds, 1993.Samuel Goldwyn <strong>on</strong>ce said:"D<strong>on</strong>'t pay any attenti<strong>on</strong> to <strong>the</strong>critics. D<strong>on</strong>'t even ignore <strong>the</strong>m."Quoted in Being Digital by NicolasNegrop<strong>on</strong>te, 1995.<str<strong>on</strong>g>Drawing</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> your creative selfI see you as an individual with creative potential for expressingyourself through drawing. My aim is to provide <strong>the</strong> means forreleasing that potential, for gaining access at a c<strong>on</strong>scious level toyour inventive, intuitive, imaginative powers that may have beenlargely untapped by our verbal, technological culture and educati<strong>on</strong>alsystem. I am going to teach you how to draw, but drawing is<strong>on</strong>ly <strong>the</strong> means, not <strong>the</strong> end. <str<strong>on</strong>g>Drawing</str<strong>on</strong>g> will tap <strong>the</strong> special abilitiesthat are right for drawing. By learning to draw you will learn tosee differently and, as <strong>the</strong> artist Rodin lyrically states, to become ac<strong>on</strong>fidant <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> natural world, to awaken your eye to <strong>the</strong> lovelylanguage <strong>of</strong> forms, to express yourself in that language.In drawing, you will delve deeply into a part <strong>of</strong> your mind too<strong>of</strong>ten obscured by endless details <strong>of</strong> daily life. From this experienceyou will develop your ability to perceive things freshly in<strong>the</strong>ir totality, to see underlying patterns and possibilities for newcombinati<strong>on</strong>s. Creative soluti<strong>on</strong>s to problems, whe<strong>the</strong>r pers<strong>on</strong>alor pr<strong>of</strong>essi<strong>on</strong>al, will be accessible through new modes <strong>of</strong> thinkingand new ways <strong>of</strong> using <strong>the</strong> power <strong>of</strong> your whole brain.<str<strong>on</strong>g>Drawing</str<strong>on</strong>g>, pleasurable and rewarding though it is, is but a keyto open <strong>the</strong> door to o<strong>the</strong>r goals. My hope is that <str<strong>on</strong>g>Drawing</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong><strong>Right</strong> <strong>Side</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Brain</strong> will help you expand your powers as anindividual through increased awareness <strong>of</strong> your own mind and itsworkings. The multiple effects <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> exercises in this book areintended to enhance your c<strong>on</strong>fidence in decisi<strong>on</strong> making andproblem solving. The potential force <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> creative, imaginativehuman brain seems almost limitless. <str<strong>on</strong>g>Drawing</str<strong>on</strong>g> may help you cometo know this power and make it known to o<strong>the</strong>rs. Through drawing,you are made visible. The German artist Albrecht Dürersaid, "From this, <strong>the</strong> treasure secretly ga<strong>the</strong>red in your heart willbecome evident through your creative work."Keeping <strong>the</strong> real goal in mind, let us begin to fashi<strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> key.6THE NEW DRAWING ON THE RIGHT SIDE OF THE BRAIN