Using a Lifeline to Give Rational Number a

Using a Lifeline to Give Rational Number a

Using a Lifeline to Give Rational Number a

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

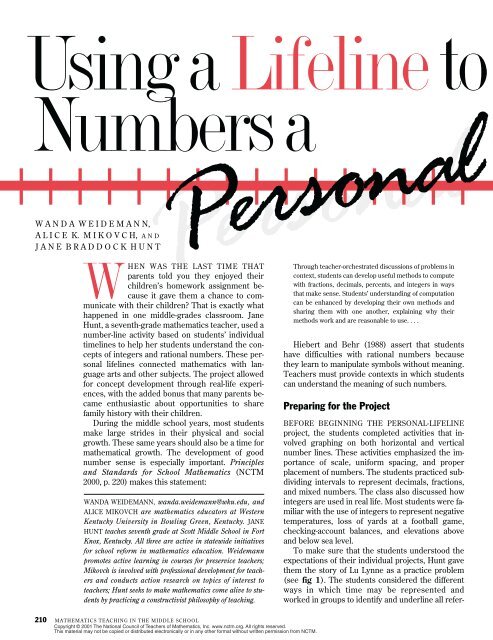

<strong>Using</strong> a <strong>Lifeline</strong> <strong>to</strong><strong>Number</strong>s aPersonalTPersonalW A N D A W E I D E M A N N,A L I C E K. M I K O V C H, A N DJ A N E B R A D D O C K H U NWHEN WAS THE LAST TIME THATparents <strong>to</strong>ld you they enjoyed theirchildren’s homework assignment becauseit gave them a chance <strong>to</strong> communicatewith their children? That is exactly whathappened in one middle-grades classroom. JaneHunt, a seventh-grade mathematics teacher, used anumber-line activity based on students’ individualtimelines <strong>to</strong> help her students understand the conceptsof integers and rational numbers. These personallifelines connected mathematics with languagearts and other subjects. The project allowedfor concept development through real-life experiences,with the added bonus that many parents becameenthusiastic about opportunities <strong>to</strong> sharefamily his<strong>to</strong>ry with their children.During the middle school years, most studentsmake large strides in their physical and socialgrowth. These same years should also be a time formathematical growth. The development of goodnumber sense is especially important. Principlesand Standards for School Mathematics (NCTM2000, p. 220) makes this statement:WANDA WEIDEMANN, wanda.weidemann@wku.edu, andALICE MIKOVCH are mathematics educa<strong>to</strong>rs at WesternKentucky University in Bowling Green, Kentucky. JANEHUNT teaches seventh grade at Scott Middle School in FortKnox, Kentucky. All three are active in statewide initiativesfor school reform in mathematics education. Weidemannpromotes active learning in courses for preservice teachers;Mikovch is involved with professional development for teachersand conducts action research on <strong>to</strong>pics of interest <strong>to</strong>teachers; Hunt seeks <strong>to</strong> make mathematics come alive <strong>to</strong> studentsby practicing a constructivist philosophy of teaching.Through teacher-orchestrated discussions of problems incontext, students can develop useful methods <strong>to</strong> computewith fractions, decimals, percents, and integers in waysthat make sense. Students’ understanding of computationcan be enhanced by developing their own methods andsharing them with one another, explaining why theirmethods work and are reasonable <strong>to</strong> use. . . .Hiebert and Behr (1988) assert that studentshave difficulties with rational numbers becausethey learn <strong>to</strong> manipulate symbols without meaning.Teachers must provide contexts in which studentscan understand the meaning of such numbers.Preparing for the ProjectBEFORE BEGINNING THE PERSONAL-LIFELINEproject, the students completed activities that involvedgraphing on both horizontal and verticalnumber lines. These activities emphasized the importanceof scale, uniform spacing, and properplacement of numbers. The students practiced subdividingintervals <strong>to</strong> represent decimals, fractions,and mixed numbers. The class also discussed howintegers are used in real life. Most students were familiarwith the use of integers <strong>to</strong> represent negativetemperatures, loss of yards at a football game,checking-account balances, and elevations aboveand below sea level.To make sure that the students unders<strong>to</strong>od theexpectations of their individual projects, Hunt gavethem the s<strong>to</strong>ry of Lu Lynne as a practice problem(see fig 1). The students considered the differentways in which time may be represented andworked in groups <strong>to</strong> identify and underline all refer-210 MATHEMATICS TEACHING IN THE MIDDLE SCHOOLCopyright © 2001 The National Council of Teachers of Mathematics, Inc. www.nctm.org. All rights reserved.This material may not be copied or distributed electronically or in any other format without written permission from NCTM.

<strong>Give</strong> <strong>Rational</strong>Touchences <strong>to</strong> time in the sample problem. They were encouraged<strong>to</strong> look for such phrases as “about thesame time”; “21 months older”; “last year”; “September20, 1986”; “3 months before”; “5 years, 3months”; and “at Christmas.” Hunt emphasized thatthe s<strong>to</strong>ry of Lu Lynne is not a good example of afamily his<strong>to</strong>ry because it lacks organization andsound grammatical structure. The purpose of thepractice problem was <strong>to</strong> help the students considerthe many ways in which one can refer <strong>to</strong> time and<strong>to</strong> notice that some times are exact, whereas othersare approximate.The students were then instructed <strong>to</strong> use 0 <strong>to</strong>represent the month of Lu Lynne’s birth. They were<strong>to</strong> find points on the number line that corresponded<strong>to</strong> the times that they had underlined in the sampleproblem. Before completing that activity, the studentsfirst needed <strong>to</strong> become accus<strong>to</strong>med <strong>to</strong> using aparticular month as the origin. Middle-grades studentstended <strong>to</strong> think of 1 January as 0, rather thanSeptember 1986. Another difficulty that studentsfaced was the tendency <strong>to</strong> label the number linewith just the years (1985, 1986, 1987, 1988, etc.)while neglecting <strong>to</strong> label the points with integers(–1, 0, 1, 2, etc.). One benefit of this project was thatstudents began <strong>to</strong> understand the importance of theorigin and the relationships of all other numbers <strong>to</strong>the origin.The students quickly realized that not all thedates could be represented by integers. This discoveryprompted a discussion about the practicalityof different representations. For example, a decimalnumeral is not a particularly good choice for representingtwo months. The students also discoveredthat some common fractions are more useful thanothers for representing time. For example, theyfound that halves, thirds, fourths, sixths, andtwelfths are useful for representing numbers ofmonths as parts of the year.Instructions: Below is a sample of a biography that might havebeen submitted by a student as part of her <strong>Lifeline</strong> Project.Work with your group <strong>to</strong> underline all of the phrases that makereferences <strong>to</strong> time. <strong>Using</strong> 0 <strong>to</strong> represent Lu Lynne’s birth date,work with your group <strong>to</strong> find points on the number line thatrepresent the times of the events you have underlined.Lu Lynne’s BiographyLu Lynne’s birthday was Sept. 20, 1986. Her brother, Billy,was 21 months older than she. Lu Lynne began <strong>to</strong> walk whenshe was 9 months old. Her family moved <strong>to</strong> Kansas when shewas about 3 years old. Her dad had graduated from school therein January of 1981 so he was glad <strong>to</strong> move back. Six monthsafter his graduation, he and Lu Lynne’s mother were married inAustin, Texas. They bought their first home in March of the followingyear. They didn’t sell that house until December of 1990.Billy was hospitalized 3 months before the house sold. He wasvery sick and had surgery at that time. Lu Lynne was the starpoint guard for her basketball team when she was 10 1/2. Shehad only begun playing the year before. Before that she had hadno interest in sports. When she was younger all she wanted <strong>to</strong>do was read. She won an award for reading at the honors’ programin May, 1994. Reading a book about basketball is whatbegan <strong>to</strong> interest her in sports. Lu Lynne’s mother graduatedfrom nursing school in June of 1997. She had had <strong>to</strong> postponecompletion of her degree because Kiki, Lu Lynne’s little brother, is5 years 3 months younger than Lu Lynne. Once Kiki enteredschool, Lu Lynne’s mother was able <strong>to</strong> finish her training. Thefamily celebrated her graduation with a trip <strong>to</strong> Disney World inAugust of the year following her graduation. They had begunsaving for vacation at Christmas in 1995.Fig. 1 Lu Lynne’s s<strong>to</strong>ryVOL. 7, NO. 4 . DECEMBER 2001 211

Hunt then placed a large number line on theboard and asked students <strong>to</strong> label and positionsticky notes on the number line <strong>to</strong> represent eachof the times in Lu Lynne’s biography. The studentshad particular difficulty in representing negativenumbers that included fractions. For example, inthe s<strong>to</strong>ry, Billy was 21 months older than Lu Lynne.The students had <strong>to</strong> determine that 21 monthsbefore Lu Lynne’s birth would be represented aseither –1 9/12 or –1 3/4. A common mistake thatstudents made was <strong>to</strong> place –1 3/4 between 0 and–1 rather than between –2 and –1.The Personal-<strong>Lifeline</strong> ProjectAFTER THE STUDENTS HAD SOME EXPERIENCEplacing rational numbers on a number line, Huntassigned the task in figure 2. She used the practiceproblem <strong>to</strong> illustrate that personal lifelines aremore interesting if they include events that happenat various times. In their projects, the studentswere required <strong>to</strong> include events that had happenedbefore and after they were born and at variousMake a personal lifeline (number line) using the month andyear of your birth as 0. Dates of events that occurred prior <strong>to</strong>your birth will be represented with negative numbers, andthose afterward will be represented with positive numbers.You may include any events and as many as you like, althoughthe minimum number (including your birth) is ten. At leastthree of those events must have occurred 3 <strong>to</strong> 5 years beforeyour birth. For example, suppose that your parents were married5 years before you were born. That event would be placedon the number line at –5 (negative 5). Or suppose that youmoved <strong>to</strong> El Paso when you were 3 years old. That event wouldbe placed on the number line at +3 (positive 3).Events should be recorded showing your mathematical power.For example, if you began <strong>to</strong> crawl at 9 months old, you wouldplace that event on the number line at 3/4, since 9 months ou<strong>to</strong>f 12 months would be the fraction 9/12, which simplifies <strong>to</strong>3/4. Choosing such events as the births of siblings, when youbegan <strong>to</strong> walk, when you learned <strong>to</strong> ride a bike, when your parentsmet, when you cut your first <strong>to</strong>oth, and so on, should befun for your family. Please do not include obvious events, suchas your first birthday (at +1), your second birthday (at +2), andso on. You should label each point with words or pictures thatcommunicate the event.Finally, you should include a reflection concerning the mathematicsyou learned or strengthened by doing this task, as wellas your thoughts concerning the task.Fig. 2 Personal-lifeline promptName of Classmate: ___________________________ Measured accurately______ At least 3 <strong>to</strong> 5 years on negative sideof lifeline______ From 12 <strong>to</strong> 14 years on positive sideof lifeline______ Positive and negative sides of lifelinein correct places______ Illustrations and labels for eachgraphed event______ At least 3 events before your birth(negative events) and 7 events afteryour birth (positive events)______ Birth as 0______ Correct numerical representation foreach point______ Used mixed numbers and a varietyof common fractions (other than justhalves, fourths, and thirds)______ Dots in proper place for each pointgraphed______ Points graphed in appropriate placeconsidering the time stated______ Integer labels above yearly tickmarks______ Year intervals divided in<strong>to</strong> useful,uniform partitions______ Other ________________________________ Other ________________________________ Other __________________________Fig. 3 Personal-lifeline student critiquetimes during the year. The students were encouraged<strong>to</strong> choose events other than those representedby whole numbers, such as first birthday, secondbirthday, and so on. The students brains<strong>to</strong>rmedpossible events that they might include in their personallifelines. The students who objected <strong>to</strong> submittingpersonal information were allowed <strong>to</strong>choose his<strong>to</strong>rical, rather than personal, events fortheir lifelines.Some events that interested students were theirparents’ first meeting or marriage, the births ofsiblings, cutting or losing a first <strong>to</strong>oth, saying firstwords, learning <strong>to</strong> ride a bike, moving <strong>to</strong> a newhome, and special vacations or celebrations, alongwith important his<strong>to</strong>rical events and births anddeaths of famous people. The students used thislist as a starting point but were encouraged <strong>to</strong> interviewfamily members and choose interestingevents in the his<strong>to</strong>ries of their families. The assignmen<strong>to</strong>ffered opportunities for earnest communicationbetween adolescents and adult familymembers.212 MATHEMATICS TEACHING IN THE MIDDLE SCHOOL

Fig. 5 Section of a student’s lifelineFig. 4 Students in conference about their lifelinesPHOTOGRAPH COURTESY OF DICK THORNTON, FORT KNOX COMMUNITY SCHOOLS; ALL RIGHTS RESERVEDThe next step was <strong>to</strong> create individual lifelines.To successfully accomplish this goal, the studentshad <strong>to</strong> make two important decisions. First, theyhad <strong>to</strong> decide what kinds of representations theywould use for the events that they had chosen.Some students chose magazine pictures, othersused pho<strong>to</strong>graphs or drawings, and some usedcombinations of two or more of these types of illustrations<strong>to</strong> represent events in their personal his<strong>to</strong>ries.Second, the students had <strong>to</strong> determine themanner in which they would represent time, especiallydivisions of time that were less than one year.Those decisions were based on the events that theyhad chosen. Hunt shared the scoring criteria in theform of a student critique sheet (see fig. 3).The students next constructed rough drafts oftheir lifelines. <strong>Using</strong> the personal-lifeline studentcritiqueform, the students met in pairs <strong>to</strong> providefeedback <strong>to</strong> each other. Some students were able <strong>to</strong>pinpoint such difficulties as misplacement of numbers,inappropriate use of scale and labels, and lackof correspondence between labels and points onthe lifeline. After these conferences, the studentsrevised their personal lifelines (see fig. 4). Theycorrected errors, added detail, and designed theiredited copies on fanfold computer paper. The studentsthen submitted their final copies for grading(see fig. 5).The last step in the project was <strong>to</strong> write a summaryof the mathematics used in creating the personallifelines. The summary was <strong>to</strong> include a descriptionof what the students had learned aboutpositive and negative rational numbers. The studentswere <strong>to</strong> explain the representations that theychose for intervals on the lifeline. In addition, theywere <strong>to</strong> describe the things that they learned fromthe project and the areas that gave them particulardifficulty.To extend this project in conjunction with alanguage-arts class, students might be asked <strong>to</strong>write family his<strong>to</strong>ries that include the events in theirpersonal lifelines. In preparation for the familyhis<strong>to</strong>rywriting task, the language arts teachermight have students as a class rewrite Lu Lynne’sbiography in a more organized sequence. This extensionwould help students transfer the symboliclifeline representation <strong>to</strong> a narrative format andwould serve as an appropriate culminating activity.The teacher’s scoring guide for the personallifelineproject appears in figure 6. In addition, thestudents displayed their final projects on the classroomwalls (see fig. 7). Other students were allowed<strong>to</strong> place sticky notes on the finished projects<strong>to</strong> make positive comments noting the differencesin the lifelines.VOL. 7, NO. 4 . DECEMBER 2001 213

CRITERIONLEVEL 4LEVEL 3LEVEL 2LEVEL 1MathematicalplacementAccurate scale withclear labeling;accurate placemen<strong>to</strong>f eventsAccurate scale;accurate placemen<strong>to</strong>f events with minorerrorsIntegers and somefractions correctlyplacedLittle attention <strong>to</strong>scale; limitedaccuracy in placemen<strong>to</strong>f eventsChoice ofeventsIncludes a varietyof significant eventsand meets criteriaoutlined in lifelinestudent critique;choice of events useswide varietyof fractionalrepresentationsIncludes eventsoutlined in lifelinestudent critique;several fractions areused but are limited<strong>to</strong> those that areeasily represented(1/2, 1/3, 1/4)Includes a limitedvariety of events oruses mainly positiveand negative integers;only basic fractionsusedIncludes a limitedvariety of events;most events correspond<strong>to</strong> positiveintegersVisualpresentationCreative representationsof events;visually appealingChoice of symbolsaccurately representsevents; visuallyappealingChoice of symbols orwords accurately representsmost events;little attention <strong>to</strong>neatnessLittle attention <strong>to</strong>visual detailWritingcomponentShows clear understandingof positiveand negative rationalnumbers, with clearrationale for choice ofintervals; insightfulself-assessmentShows clear understandingof positiveand negative rationalnumbers and goodrationale for choiceof intervals; lists (withexamples) someareas of learning ordifficultyShows basic progressin learning aboutpositive and negativeintegers and choiceof intervals; listssome areas oflearning or difficultyShows little understandingof positiveand negative integersand choice of intervals;gives littleattention <strong>to</strong> areas oflearning or difficultyFamily his<strong>to</strong>ry(optional)Well sequenced andorganized; grammaticallycorrect; givesinteresting overviewof family lifeWell sequenced andorganized; only minorgrammatical errors;events accuratelydescribedSome attention <strong>to</strong>organization andsequencing; somegrammatical errors;events accuratelydescribedLittle attention <strong>to</strong>organization andsequencing; manygrammatical errors;little detail in descriptionof eventsFig. 6 Scoring guide for personal-lifeline taskConnectionsTHIS ACTIVITY CAN EASILY BE ADAPTED TO BEcomepart of an interdisciplinary unit on his<strong>to</strong>rical,community, or governmental events. For example,<strong>to</strong> connect the personal timeline with his<strong>to</strong>ry, the 0coordinate might represent the signing of the Declarationof Independence. Events leading up <strong>to</strong> independencewould be represented by negativenumbers, whereas events that occurred after thesigning of the document would be represented bypositive numbers. Another project might use 0 <strong>to</strong>represent 1900 and show pictures depicting inventionsthat affect the lives of students <strong>to</strong>day in transportation,communications, and other fields.For community events, the coordinate for 0might represent the date that the school wasopened. Events before the building of the schoolmight include the charter of the <strong>to</strong>wn, the constructionof important his<strong>to</strong>rical buildings, and importantmiles<strong>to</strong>nes in the his<strong>to</strong>ry of the <strong>to</strong>wn. Recent eventsmight include school awards, major athletic competitions,or community celebrations.Governmental connections could include the inaugurationof presidents, the granting of statehood,and the passing of important pieces of legislation.The choice of the event represented by 0 is not significant;the placement of the events on the numberline will reveal students’ understanding of the mathematicalpart of the interdisciplinary assignment.214 MATHEMATICS TEACHING IN THE MIDDLE SCHOOL

Fig. 7 A display of student lifelinesConclusionPHOTOGRAPH COURTESY OF DICK THORNTON, FORT KNOX COMMUNITY SCHOOLS; ALL RIGHTS RESERVEDabout one another and help establish a sense of“family” among students.Another advantage of this task is that it can beadapted <strong>to</strong> many different learning levels. The taskcan be used <strong>to</strong> introduce graphing on the positivenumber line. Younger students can label their lifelineswith years only, using a specific year as the origin.For more advanced students, this activity mightbe used <strong>to</strong> review graphing on the number line beforemoving on <strong>to</strong> graphing in the coordinate plane.In short, this activity not only presents a practicalapplication of important mathematical conceptsbut also encourages the development of socialskills that are essential in the middle grades andprovides a link between the school and the family.Most important, however, the activity is fun andmeaningful for students, families, and teachers.ReferencesTHIS PROJECT PROVED TO BE REWARDING INmany ways. The students strengthened their understandingof positive and negative numbers, especiallythose involving fractions; learned <strong>to</strong> pay attention<strong>to</strong> scale and <strong>to</strong> measure accurately; andenhanced their graphing skills on the number line.This activity changed the emphasis inthis unit from following a procedure <strong>to</strong> placenumbers on a number line <strong>to</strong> completing anapplication task. The students used problemsolving <strong>to</strong> determine scale, <strong>to</strong> choose methodsfor representing numbers, and <strong>to</strong> understandthat the origin can represent any specificpoint in time. Valuable connectionscould be established between mathematicsand language arts with the addition of therequirement of a written his<strong>to</strong>ry of the timeframes represented by the number line.The most powerful, unexpected benefi<strong>to</strong>f the lifeline project was parental enthusiasmfor the activity. Adult family memberswere delighted <strong>to</strong> have opportunities <strong>to</strong>share important events in their personal his<strong>to</strong>rieswith their adolescent children. Oneparent remarked that he had, in essence, introducedfamily members <strong>to</strong> his child asthey worked <strong>to</strong>gether <strong>to</strong> choose events thathappened before the child’s birth. Anotherparent commented that the student had <strong>to</strong>explain the placement of negative numbers.The students enjoyed learning about theirown families and the families of others. Becausefamilies and teams are important inthe middle school environment, this activitywas used near the beginning of the schoolyear <strong>to</strong> give students a chance <strong>to</strong> learnHiebert, James, and Merlyn J. Behr, eds. <strong>Number</strong> Conceptsand Operations in the Middle Grades. Hillsdale,N.J.: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1988.National Council of Teachers of Mathematics (NCTM).Principles and Standards for School Mathematics.Res<strong>to</strong>n, Va.: NCTM, 2000. CVOL. 7, NO. 4 . DECEMBER 2001 215