Criminology Law & Society Research Newsletter

owcwytp

owcwytp

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Volume 1• Issue 1<br />

November 2016<br />

<strong>Criminology</strong>, <strong>Law</strong>, & <strong>Society</strong> <strong>Research</strong> <strong>Newsletter</strong><br />

Click to share the newsletter!<br />

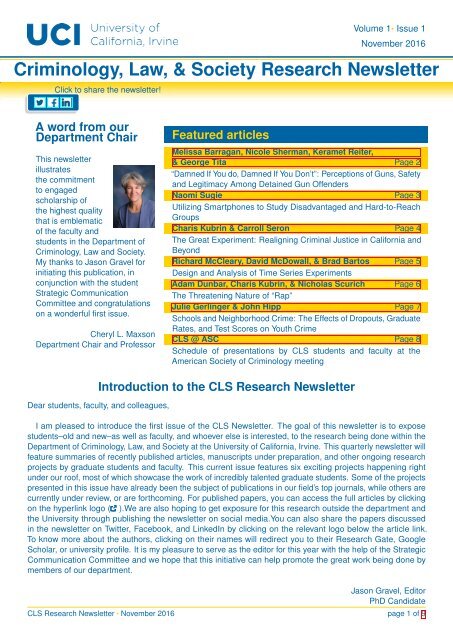

A word from our<br />

Department Chair<br />

This newsletter<br />

illustrates<br />

the commitment<br />

to engaged<br />

scholarship of<br />

the highest quality<br />

that is emblematic<br />

of the faculty and<br />

students in the Department of<br />

<strong>Criminology</strong>, <strong>Law</strong> and <strong>Society</strong>.<br />

My thanks to Jason Gravel for<br />

initiating this publication, in<br />

conjunction with the student<br />

Strategic Communication<br />

Committee and congratulations<br />

on a wonderful first issue.<br />

Cheryl L. Maxson<br />

Department Chair and Professor<br />

Featured articles<br />

Melissa Barragan, Nicole Sherman, Keramet Reiter,<br />

& George Tita Page 2<br />

“Damned If You do, Damned If You Don’t”: Perceptions of Guns, Safety<br />

and Legitimacy Among Detained Gun Offenders<br />

Naomi Sugie Page 3<br />

Utilizing Smartphones to Study Disadvantaged and Hard-to-Reach<br />

Groups<br />

Charis Kubrin & Carroll Seron Page 4<br />

The Great Experiment: Realigning Criminal Justice in California and<br />

Beyond<br />

Richard McCleary, David McDowall, & Brad Bartos Page 5<br />

Design and Analysis of Time Series Experiments<br />

Adam Dunbar, Charis Kubrin, & Nicholas Scurich Page 6<br />

The Threatening Nature of “Rap”<br />

Julie Gerlinger & John Hipp Page 7<br />

Schools and Neighborhood Crime: The Effects of Dropouts, Graduate<br />

Rates, and Test Scores on Youth Crime<br />

CLS @ ASC Page 8<br />

Schedule of presentations by CLS students and faculty at the<br />

American <strong>Society</strong> of <strong>Criminology</strong> meeting<br />

Dear students, faculty, and colleagues,<br />

Introduction to the CLS <strong>Research</strong> <strong>Newsletter</strong><br />

I am pleased to introduce the first issue of the CLS <strong>Newsletter</strong>. The goal of this newsletter is to expose<br />

students–old and new–as well as faculty, and whoever else is interested, to the research being done within the<br />

Department of <strong>Criminology</strong>, <strong>Law</strong>, and <strong>Society</strong> at the University of California, Irvine. This quarterly newsletter will<br />

feature summaries of recently published articles, manuscripts under preparation, and other ongoing research<br />

projects by graduate students and faculty. This current issue features six exciting projects happening right<br />

under our roof, most of which showcase the work of incredibly talented graduate students. Some of the projects<br />

presented in this issue have already been the subject of publications in our field’s top journals, while others are<br />

currently under review, or are forthcoming. For published papers, you can access the full articles by clicking<br />

on the hyperlink logo ( ).We are also hoping to get exposure for this research outside the department and<br />

the University through publishing the newsletter on social media.You can also share the papers discussed<br />

in the newsletter on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn by clicking on the relevant logo below the article link.<br />

To know more about the authors, clicking on their names will redirect you to their <strong>Research</strong> Gate, Google<br />

Scholar, or university profile. It is my pleasure to serve as the editor for this year with the help of the Strategic<br />

Communication Committee and we hope that this initiative can help promote the great work being done by<br />

members of our department.<br />

Jason Gravel, Editor<br />

PhD Candidate<br />

CLS <strong>Research</strong> <strong>Newsletter</strong> • November 2016 page 1 of 9

Volume 1• Issue 1<br />

November 2016<br />

“Damned If You do, Damned If You Don’t”:<br />

Perceptions of Guns, Safety and Legitimacy Among Detained Gun<br />

Offenders<br />

Melissa Barragan 1 , Nicole Sherman, Keramet Reiter, & George E. Tita<br />

Barragan, M., et al. (2016). Criminal Justice & Behavior, 43(1),140-155.<br />

1 barragm1@uci.edu<br />

Understanding the factors that motivate illicit gun<br />

behavior is necessary for shaping gun policies<br />

that will effectively deter future gun offenders<br />

and maintain public safety. Although some studies<br />

suggest that negative perceptions of the law and<br />

safety concerns can influence gun offending patterns,<br />

few have examined how such perceptions develop<br />

and, importantly, how these legal and extra-legal<br />

factors interact to shape individual compliance and<br />

the legitimacy of gun law more generally. To address<br />

these gaps in the literature, this paper draws upon<br />

140 in-depth interviews with gun offenders detained in<br />

Los Angeles County Jails. By leveraging the voices of<br />

serious gun offenders, this paper critically interrogates<br />

the theorized relationship between both guns and<br />

safety and legitimacy and compliance.<br />

Methodology<br />

The data presented in this paper were collected<br />

as part of a multi-city project examining illegal<br />

gun markets from the perspective of detained gun<br />

offenders. Interviews were conducted at four Los<br />

Angeles County Jails between January and October<br />

of 2014. Participants were randomly selected from<br />

a list of detainees held on gun-related charges (e.g.,<br />

felon in possession of a firearm), excluding only those<br />

with safety or mental health designations.<br />

In total,<br />

we interviewed 140 people and 75 refused, for a<br />

final participation rate of 65%. A modified grounded<br />

theory approach was used to develop analytic codes<br />

inductively from the interview data [1].<br />

Results & Conclusions<br />

Findings suggest that the legitimacy-compliance<br />

association is a non-linear, multi-faceted process,<br />

conditioned by a variety of experiences and<br />

perspectives. At the heart of this relationship is<br />

perceived safety. A majority of respondents live<br />

in violence-ridden communities, have been witness<br />

to or been victims of gun violence, and have<br />

experienced myriad abuses at the hands of the law.<br />

Under such circumstances, guns offered respondents<br />

an immediate and reasonable safety-management<br />

strategy.<br />

Yet willingness to subvert the law did not mean<br />

that respondents disavowed the law completely.<br />

Respondents typically perceived the public safety<br />

function of gun law as legitimate, and agreed that<br />

the law should regulate gun possession among those<br />

who inflict the most harm (e.g., violent offenders and<br />

the mentally unstable). Respondents also generally<br />

agreed that the police play an important role in<br />

maintaining community safety.<br />

Unfortunately, the collective, protective utility of both<br />

gun laws and the police appeared to be compromised<br />

by adverse experiences with community violence<br />

and police. Regardless of engagement in criminal<br />

activity, most respondents feared that they would<br />

fall victim violence, and particularly gang violence, if<br />

they did not have a gun. Repeated experiences with<br />

police harassment and abuse further enhanced these<br />

feelings of physical insecurity by tainting respondents’<br />

willingness to trust and cooperate with the authorities.<br />

Taken together, what we have is a ripple effect: if safety<br />

is tenuous, so too is the legitimacy of gun law and, thus,<br />

compliance.<br />

These findings have important implications for both<br />

theory and policy. <strong>Research</strong> shows that gun policies<br />

are generally crafted according deterrence principles.<br />

Although this article did not explore perceptions<br />

of certainty or celerity, respondents’ willingness to<br />

circumvent the law in spite of punitive restrictions<br />

suggests that severity alone is not sufficient to deter<br />

gun offenders. For our sample, fear of crime and<br />

victimization–both by gang members and the police<br />

alike–outweighed fear of punishment. Failure to<br />

address these underlying fears and realities within<br />

communities highly effected by gun risks undermining<br />

the legitimacy and impact of well-intentioned gun<br />

policies.<br />

CLS <strong>Research</strong> <strong>Newsletter</strong> • November 2016 page 2 of 9

Utilizing Smartphones to Study Disadvantaged<br />

and Hard-to-Reach Groups<br />

Naomi F. Sugie 1<br />

Sugie, N. F. (2016). Sociological Methods & <strong>Research</strong>. Published online.<br />

Volume 1• Issue 1<br />

November 2016<br />

1 nsugie@uci.edu<br />

Mobile technologies, specifically smartphones,<br />

offer social scientists a potentially powerful<br />

approach to examine the social world. They<br />

enable researchers to collect information that was<br />

previously unobservable or difficult to measure,<br />

expanding the realm of empirical investigation.<br />

For research that concerns resource-poor and<br />

hard-to-reach groups, smartphones may be<br />

particularly advantageous by lessening sample<br />

selection and attrition and by improving measurement<br />

quality of irregular and unstable experiences. At the<br />

same time, smartphones are nascent social science<br />

tools, particularly with less advantaged populations<br />

that may have different phone usage patterns and<br />

privacy concerns.<br />

Methodology<br />

This article discusses the strengths and potential<br />

challenges of utilizing smartphones as research tools<br />

among hard-to-reach groups with less technology<br />

experience. I focus on four main issues of<br />

concern for researchers considering smartphone<br />

studies with similar groups: sample selection and<br />

attrition, measurement of irregular and changeable<br />

patterns, missing data, and researcher effects. I<br />

also discuss several lessons learned that describe<br />

specific strategies for gaining participant trust and<br />

protecting privacy, methods to address heterogeneous<br />

technological skills of participants, and questions to<br />

consider when assessing options for phones and data<br />

plans. I illustrate all of these topics with findings from<br />

the Newark Smartphone Reentry Project (NSRP). The<br />

NSRP sampled participants from a complete census of<br />

eligible men recently released from prison and under<br />

supervision with the New Jersey Parole Board. 135<br />

men received smartphones and phone plans and were<br />

followed via the phones for three months. A smaller<br />

group was also followed with interviews for comparison<br />

purposes.<br />

Results<br />

One of the main advantages of using smartphones<br />

to collect data was that participants seemed to prefer<br />

the use of phones, as opposed to interviews. This<br />

finding was demonstrated both by participants’ higher<br />

initial take-up rate and their statements about the<br />

convenience of smartphone surveys. For groups<br />

that are typically hard to reach, this is a clear<br />

advantage compared to interview or survey methods.<br />

Smartphones also facilitate the collection of detailed<br />

behavioral measures that are often not possible to<br />

obtain with other methods, such as measures of<br />

everyday geographic mobility and social networks.<br />

Moreover, they enable the collection of frequent<br />

self-report answers, which is a particular benefit<br />

for researchers studying groups, topics, or contexts<br />

that are characterized by irregular or changeable<br />

experiences. For researchers considering smartphone<br />

projects, however, the potential Hawthorne effects of<br />

frequent surveys, as well as the provision of phones<br />

and data plans, should be assessed within the scope<br />

and aims of the specific project. As I found in the<br />

NSRP, participants believed that the project provided<br />

benefits during their job search and that their job<br />

search changed as a result of their participation. At<br />

the same time, however, participants in the interview<br />

group also voiced similar beliefs at similar rates.<br />

Conclusions<br />

Social science researchers might consider<br />

capitalizing on researcher effects by incorporating<br />

smartphone-based interventions or experimental<br />

designs to test theories of social behavior; these types<br />

of smartphone-based interventions are increasingly<br />

prominent in other disciplines, particularly health. As<br />

social and communication tools, smartphones are well<br />

suited to social science interventions.<br />

CLS <strong>Research</strong> <strong>Newsletter</strong> • November 2016 page 3 of 9

Volume 1• Issue 1<br />

November 2016<br />

The Great Experiment:<br />

Realigning Criminal Justice in California and Beyond<br />

Charis E. Kubrin 1 , & Carroll Seron<br />

Kubrin, C. E., & Seron, C. (2016). Special issue of the ANNALS of the American<br />

Academy of Political and Social Science, 664.<br />

1 ckubrin@uci.edu<br />

Until recently, the state of California was home<br />

to the nation’s largest state prison system.<br />

California’s prison population peaked at 173,000<br />

in 2006, despite the fact that its prisons were designed<br />

to hold a maximum of 79,858 people. In 2011,<br />

the Supreme Court decided that prison conditions<br />

in California were tantamount to cruel and unusual<br />

punishment and required the State to bring its prison<br />

population down to 137.5 percent of design capacity<br />

by reducing the rolls by some 33,000 inmates over a<br />

two-year timeframe. In response, California enacted<br />

a controversial law -Public Safety Realignment -<br />

which transferred responsibility for lower-level felony<br />

offenders from the state correctional system to 58<br />

county jail and probation systems. Today, there are<br />

146,000 fewer Californians supervised either in prison,<br />

jail, parole, or probation than there were prior to<br />

Realignment. The realignment of California corrections<br />

has been described as “the biggest criminal justice<br />

experiment ever conducted in America.” How did<br />

California end up in the Supreme Court? How has<br />

Realignment been implemented in the State? Is the<br />

Realignment experiment working? Going forward,<br />

what can we learn from California?<br />

Objectives<br />

With funding from the National Science Foundation,<br />

the University of California Office of the President, and<br />

the University of California, Irvine, we held a two-day<br />

workshop on prison downsizing and criminal justice<br />

reform at UCI in October of 2014. The goal of the<br />

workshop was to catalyze an interdisciplinary research<br />

agenda to address a series of questions about<br />

Realignment and its impact and to produce findings<br />

that can be valuable to an array of stakeholders,<br />

from the Governor to local officials charged with<br />

implementing Realignment. We conceived of this as a<br />

discussion of the arc of Realignment, from the “cause<br />

lawyering” initiative and the Constitutional questions at<br />

play to its impact on crime and criminal justice policy<br />

and practice. Findings were published in a special<br />

issue of the ANNALS. This volume of The ANNALS<br />

is the first systematic, scientific analysis of the recent<br />

realignment of California corrections.<br />

Results & Conclusions<br />

New historical research describes the social<br />

conditions that undergirded California’s prison buildup,<br />

a politics of avoidance and passing the buck that<br />

influenced decades of policy choices about crime<br />

and punishment, and the role of public interest<br />

lawyers in developing and sustaining the legal<br />

claims that led to the 2011 Supreme Court decision.<br />

Reductions in California incarcerations were neither<br />

politically expedient nor particularly popular. Years<br />

of sustained (and barely funded) “cause lawyering”<br />

was necessary to shepherd change. Historical<br />

analysis also suggests that humanitarian and legal<br />

challenges to hyper-incarceration were aided by the<br />

Great Recession; an extraordinary need for austerity<br />

and financial prudence set the stage for difficult policy<br />

decision-making.<br />

The great shift in responsibility for low-level<br />

offenders from the state to the counties is a remarkable<br />

(and rare) example of devolution of power and<br />

authority. Implementation of Realignment has varied<br />

considerably across counties:some have chosen to<br />

reduce prison populations by adding more bed space<br />

in jails, while others have elected to place more<br />

individuals on probation, and still others have provided<br />

greater rehabilitative services to parolees. Despite<br />

this variation, it is clear that California has progressed<br />

rapidly toward its goal of reducing its prison population<br />

and complying with the Supreme Court order.<br />

Is California becoming more dangerous because<br />

of Realignment? The empirical work published here<br />

suggests that it is not. New research on crime<br />

in the aftermath of Realignment shows that prison<br />

downsizing has had negligible consequences for crime,<br />

one way or another. As one expert puts it, the<br />

criminogenic consequences of Realignment “have<br />

been so far both modest and benign.” County-level<br />

analyses suggest that the release of low-level felony<br />

offenders from state to local governments may actually<br />

improve recidivism outcomes, depending on the<br />

approach that local governments take. Counties that<br />

put resources into reentry services and programs have<br />

seen better recidivism outcomes than those that put<br />

money into more police, sheriffs, or jail beds.<br />

CLS <strong>Research</strong> <strong>Newsletter</strong> • November 2016 page 4 of 9

Design and Analysis of Time Series Experiments<br />

Richard McCleary, David McDowall 1 , & Brad Bartos 2<br />

Volume 1• Issue 1<br />

November 2016<br />

McCleary, R., et al. (Forthcoming, 2017). Oxford University Press.<br />

1 SUNY Albany 2 bbartos@uci.edu<br />

Design and Analysis of Time Series Experiments<br />

develops a comprehensive set of models and<br />

methods for drawing causal inferences from<br />

time series. Situations where the added expense<br />

of a time series design is warranted fall into two<br />

overlapping categories. The first category consists<br />

of situations where the nature of the underlying<br />

phenomenon is obscured by trends and cycles.<br />

A well-constructed time series model may reveal<br />

the nature of the underlying phenomenon. The<br />

second category consists of situations where a known<br />

intervention and an appropriate control time series<br />

are available. In those situations, a well-designed<br />

time series experiment can support explicitly causal<br />

inferences that are not supported by less expensive<br />

before-after designs. Example analyses of social,<br />

behavioral, and biomedical time series illustrate a<br />

general strategy for building AutoRegressive Integrated<br />

Moving Average (ARIMA) impact models.<br />

Forecasting<br />

While the ”best” ARIMA model will outperform other<br />

forecasting models in the short and medium-run,<br />

long-horizon ARIMA forecasts grow increasingly<br />

inaccurate with diminished utility to the forecaster.<br />

Although the principles of forecasting help provide<br />

deeper insight into the nature of ARIMA models and<br />

modeling, the forecasts themselves are ordinarily of<br />

limited practical value. Forecasting can provide useful<br />

guidance to analysts choosing between two competing<br />

univariate models.<br />

While forecasting accuracy is<br />

only one of many criteria that might be considered,<br />

other things being equal, it is fair to say that a<br />

statistically adequate model of a process should<br />

provide reasonable forecasts of the future.<br />

ARIMA Modeling<br />

The general ARIMA model can be written as the sum<br />

of noise and exogenous components. If an exogenous<br />

impact is trivially small, the noise component can<br />

be identified with the conventional modeling strategy.<br />

If the impact is non-trivial or unknown, the sample<br />

AutoCorrelation Function (ACF) will be distorted in<br />

unknown ways. Although this problem can be solved<br />

most simply when the outcome of interest time series<br />

is long and well-behaved, these time series are<br />

unfortunately uncommon. The preferred alternative<br />

requires that the structure of the intervention is known,<br />

allowing the noise function to be identified from the<br />

residualized time series. Although few substantive<br />

theories specify the ”true” structure of the intervention,<br />

most specify the dichotomous onset and duration of an<br />

impact. The classic Box-Jenkins-Tiao model-building<br />

strategy is supplemented with recent auxiliary tests for<br />

transformation, differencing and model selection.<br />

Validity & Causal Inference<br />

The validity of causal inferences is approached<br />

from two complementary directions. The four-validity<br />

system of Cook and Campbell relies on ruling out<br />

discrete threats to statistical conclusion, internal,<br />

construct and external validity. The common threats to<br />

statistical conclusion validity or, ”validity of inferences<br />

about the correlation (covariance) between treatment<br />

and outcome”, can arise or become plausible through<br />

either model misspecification or through hypothesis<br />

testing.<br />

Rubin Causality & Synthetic Controls<br />

Under the assumption that subjects were randomly<br />

assigned to the treatment and control groups, Rubin’s<br />

causal model allows one to estimate the unobserved<br />

causal parameter from observed data. The Rubin<br />

system causal model relies on the identification<br />

of a control time series chosen so as to render<br />

plausible threats to internal validity implausible.<br />

An appropriate control time series may not exist,<br />

however, an ideal time series may be possible to<br />

construct. The two approaches to causal validity<br />

are shown to be complementary and are illustrated<br />

with a construction of a synthetic control time series.<br />

Synthetic Control Group models construct a control<br />

time series that optimally recreates the treated unit’s<br />

pre-intervention trend using a combination of untreated<br />

donor pool units. Example analyses make optimal<br />

use of graphical illustrations. Mathematical methods<br />

used in the example analyses are explicated in<br />

technical appendices, including expectation algebra,<br />

sequences and series, maximum likelihood, Box-Cox<br />

transformation analyses and probability<br />

CLS <strong>Research</strong> <strong>Newsletter</strong> • November 2016 page 5 of 9

The Threatening Nature of “Rap”<br />

Adam Dunbar 1 , Charis E. Kubrin, & Nicholas Scurich<br />

Volume 1• Issue 1<br />

November 2016<br />

Dunbar, A., et al. (2016). Psychology, Public Policy, and <strong>Law</strong>, 22(3), 280-292.<br />

1 dunbara@uci.edu<br />

In 2013, university student and aspiring rapper,<br />

Olutosin Oduwole, was charged with making a<br />

terrorist threat after the police found a slip of paper<br />

in his car. The paper had multiple rap verses on one<br />

side and unrhymed lyrics on the other side, lyrics<br />

which described a “murderous rampage similar to<br />

the Virginia Tech shooting.” Even though Oduwole<br />

explained that the verses were simply notes for a new<br />

rap song he was working on and even though he did<br />

not communicate a threat to anyone, he was charged<br />

with communicating a terrorist threat. Some years<br />

later, a jury found him guilty and he was sentenced<br />

to five years in prison. Oduwole’s case reflects a new<br />

disturbing trend–police and prosecutors are treating<br />

rap lyrics as an admission of guilt or evidence of intent<br />

to commit a crime, rather than as art or entertainment.<br />

These cases typically involve aspiring rappers–nearly<br />

all of whom are young black men from impoverished<br />

communities–who are mimicking the lyrical style and<br />

content of more famous rappers. Critics fear that<br />

prosecutors adopt this strategy because jurors may<br />

not understand the history and genre conventions of<br />

rap music, and instead, may rely on stereotypes when<br />

evaluating the threatening and autobiographical nature<br />

of the lyrics. Next to no research has directly tested<br />

the impact of rap music stereotypes on evaluations of<br />

violent lyrics. The current study addresses this gap in<br />

the literature.<br />

Methodology<br />

This study presents 3 experiments that examine the<br />

impact of genre-specific stereotypes on the evaluation<br />

of violent song lyrics by manipulating the musical<br />

genre while holding constant the actual lyrics. In<br />

•Adam Dunbar, PhD Candidate, received the 2016 Student Paper<br />

Award from the Division of Experimental <strong>Criminology</strong> of the American<br />

<strong>Society</strong> of <strong>Criminology</strong> for his work on ”The Threatening Nature of<br />

Rap Music.”<br />

•Professor Charis Kubrin gave a TEDx talk about her work on the use<br />

of rap lyrics in the courtroom. Click here to watch.<br />

study 1, participants were randomly assigned to one<br />

of two conditions, which experimentally manipulated<br />

the genre of the lyrics (rap or country). However, all<br />

participants read the same violent lyrics. After reading<br />

the lyrics, participants evaluated them by responding<br />

to 14 different items related to the offensiveness of the<br />

lyrics, the threatening nature of the lyrics, the literality<br />

of the lyrics (or how true the lyrics were perceived to<br />

be by respondents), and the need for the song to be<br />

regulated. Study 2 was a conceptual replication of<br />

study 1, wherein the same study design was employed<br />

but with a different set of lyrics. Study 3 experimentally<br />

manipulated the genre label of the lyrics as well as the<br />

race of the author of the lyrics in order to disentangle<br />

the genre label effect with any potential race effect.<br />

The third study also added a control condition where<br />

no genre label was noted in order to test whether the<br />

country label engenders positive or neutral evaluations<br />

and rap negative evaluations.<br />

Results & Conclusions<br />

Study 1 found that participants deemed identical<br />

lyrics more literal, offensive, and in greater need<br />

of regulation when they were characterized as rap<br />

rather than country. Study 2 again detected this effect<br />

with a different set of violent lyrics, underscoring the<br />

robustness of the effect. For study 3, a main effect<br />

was detected for the genre, with rap evaluated more<br />

negatively than country and the “no label” control<br />

condition. However, no effects were found for the race<br />

of the lyrics’ author nor were interactions detected.<br />

Collectively, these findings highlight the possibility that<br />

rap lyrics could inappropriately impact jurors when<br />

admitted as evidence to prove guilt.<br />

Additional information<br />

CLS <strong>Research</strong> <strong>Newsletter</strong> • November 2016 page 6 of 9

Volume 1• Issue 1<br />

November 2016<br />

Schools and Neighborhood Crime:<br />

The Effects of Dropouts, Graduate Rates, and Test Scores on Youth<br />

Crime<br />

Julie Gerlinger 1 , & John R. Hipp<br />

Gerlinger, J., & Hipp, J. R. Manuscript under review.<br />

1 jgerlinger@uci.edu<br />

From a criminological perspective, attachment to<br />

school indicates a commitment to conventional<br />

beliefs and goals and is a means of deviance<br />

avoidance. Studies on the effects of schools on<br />

neighborhood crime have generally focused on the<br />

simple presence of or distance to a school rather than<br />

individual school characteristics. Additionally, previous<br />

work utilizes crime, as opposed to juvenile crime, to<br />

investigate this phenomenon–a practice we call into<br />

question<br />

Objectives<br />

We focus on three school characteristics that,<br />

according to social disorganization and routine activity<br />

theories, might affect local crime. More specifically,<br />

we use negative binomial and logistic regression<br />

models to estimate the effects of high school<br />

dropouts, graduate rates, and test scores on juvenile<br />

crime using Orange County, CA as a research site.<br />

crosswalk provided by CDE. Demographic data come<br />

from Census and the American Community Survey<br />

(ACS), and point crime data were collected from the<br />

Orange County Sheriff’s Department. For block-level<br />

data that were not provided by Census or ACS, these<br />

data were imputed using information about the block<br />

groups. We generate a two-mile spatial buffer with<br />

an inverse distance decay function for each school<br />

characteristic so that any school within these buffers<br />

is associated with the focal block.<br />

Figure 1: Public High Schools in the Orange County<br />

Sheriff’s Department Patrol Area<br />

Methods<br />

We combine a number of datasets to create<br />

block-level data from 2000 to 2012. Several school<br />

datasets were retrieved from the California Department<br />

of Education (CDE), which we merge with geographic<br />

identifiers from Common Core for Data using a<br />

Figure 2: Two-Mile Spatial Buffer Example<br />

Results<br />

We find that areas with a higher number of dropouts<br />

are associated with increased juvenile crime (i.e.,<br />

aggravated assault, burglary, and robbery), but schools<br />

with high graduate rates or test scores seem to have<br />

no significant effect on local crime. We also compare<br />

models that predict juvenile crime with models that<br />

predict crime, generally, and argue that juvenile crime<br />

is the theoretically appropriate crime measure.<br />

Conclusions<br />

Our study’s findings, in conjunction with the<br />

numerous long-term socioeconomic benefits reported<br />

for those who complete high school, stresses the<br />

importance of keeping students engaged in school.<br />

We encourage schools to attempt to detect early<br />

warning signs while the student is in middle school and<br />

intervene before it results in serious problem behaviors.<br />

To interrupt this process is to provide the student, the<br />

student’s family, and the community with an opportunity<br />

for a safer and brighter future.<br />

CLS <strong>Research</strong> <strong>Newsletter</strong> • November 2016 page 7 of 9

CLS @ ASC<br />

Volume 1• Issue 1<br />

November 2016<br />

American <strong>Society</strong> of <strong>Criminology</strong> Annual Meeting, New Orleans, LA, November 16-19th, 2016<br />

Time Title Authors Place<br />

Wednesday, November 16th<br />

8:00 to 9:20am Can At-Risk Youth be Diverted from Crime? A Meta-Analysis of<br />

Jennifer Wong, Jessica Bouchard, Jason Gravel, Cambridge, 2nd Level<br />

Restorative Diversion Programs<br />

Martin Bouchard, and Carlo Morselli<br />

8:00 to 9:20am Policing the Mentally Ill in Los Angeles Natalie A. Pifer Marlborough B, 2nd Level<br />

8:00 to 9:20am Prison Displacements and Life After Mass Incarceration for the Elderly Anjuli C. Verma Marlborough B, 2nd Level<br />

9:30 to 10:50am A Call for Action: Examining How Residents Mobilize to Effectively James Wo<br />

Prince of Wales, 2nd Level<br />

Combat Crime<br />

9:30 to 10:50am Slumcare and the Fail-State Kenneth A. Cruz Quarterdeck A, Riverside Complex<br />

11:00 to 12:20pm The Varying Effects of Incarceration, Conviction, and Arrest on Wealth Michelle Maroto, and Bryan Sykes<br />

Grand Salon 9, 1st Level<br />

Outcomes Among Young Adults<br />

12:30 to 1:50pm Police Brutality and the Ungendering of Black Women Afiya Browne Fulton, 3rd Level<br />

12:30 to 1:50pm White-Collar Crime and Garland’s Culture of Control Puma Shen Port, Riverside Complex<br />

2:00 to 3:20pm Gang Identity, Performance, and Conflict Transformation in the Online Jenny West-Fagan<br />

Grand Ballroom A, 1st Level<br />

World<br />

2:00 to 3:20pm Frank Tannenbaum: The Making of a Convict Criminologist Elliott Currie Grand Salon 10, 1st Level<br />

2:00 to 3:20pm Progressive Punishment: Job Loss, Jail Growth and the Neoliberal Logic Keramet Reiter<br />

Steering, Riverside Complex<br />

of Carceral Expansion<br />

3:30 to 4:50pm <strong>Criminology</strong> so white? How race/ethnicity is represented, presented, Amanda M. Petersen, and Jody Sundt<br />

Steering, Riverside Complex<br />

and discussed in criminology and criminal justice research<br />

3:30 to 4:50pm Wrongful Conviction Reforms in the United States and the United C. Ronald Huff, and Michael Naughton Grand Salon 12, 1st Level<br />

Kingdom: Taking Stock<br />

3:30 to 4:50pm The Wrong Crowd Effect: Is Police Targeting Contagious? Jason Gravel Marlborough A, 2nd Level<br />

3:30 to 4:50pm Future-Proofing, Collateral Hardening and Decreasing Room for Error in Lori Sexton, Keramet Reiter, and Jennifer Grand Salon 6, 1st Level<br />

Danish Prisons<br />

Sumner<br />

3:30 to 4:50pm Crack as Proxy: Aggressive Federal Prosecutions as Institutional Marisa Omori, and Mona Lynch<br />

Grand Ballroom B, 1st Level<br />

Racism?<br />

5:00 to 6:20pm Aid-in-Dying Legal Reform: An Analysis of Three Countries John Dombrink Grand Ballroom A, 1st Level<br />

Thursday, November 17th<br />

8:00 to 9:20am Aiyana Stanley-Jones Jasmine Montgomery Grand Salon 24, 1st Level<br />

8:00 to 9:20am Discourse, Logic, and Decision-Making in Parole Eligibility Hearings Kristen Maziarka, and Emma Conner Grand Salon 18, 1st Level<br />

9:30 to 10:50am Dog Whistles No More: (R)(E)Racing Borders and the Preservation of Kasey C. Ragan, and Raymond Michalowski Grand Salon 9, 1st Level<br />

the Wages of Whiteness<br />

9:30 to 10:50am How Does the Spatial Distribution of Urban Growth Impact Crime Across Kevin Kane, and John R. Hipp<br />

Grand Ballroom C, 1st Level<br />

Cities?<br />

9:30 to 10:50am Whither Park or Withering Park? Extending <strong>Research</strong> on the Nicholas Branic, Charis Kubrin, and John R. Grand Ballroom C, 1st Level<br />

Parks-Crime Relationship<br />

Hipp<br />

9:30 to 10:50am Different than the Sum of its Parts: Examining the Unique Impacts of Charis Kubrin, John R. Hipp, and Young-An Kim Grand Ballroom C, 1st Level<br />

Immigrant Groups on Neighborhood Crime Rates<br />

9:30 to 10:50am Third Places and the Development of Social Cohesion across Seth Williams<br />

Grand Ballroom C, 1st Level<br />

Neighborhood Types<br />

12:30 to 1:50pm Unleashing the Power of Open Government Datasets in <strong>Criminology</strong> Christopher Jay Bates, and John R. Hipp Chequers, 2nd Level<br />

12:30 to 1:50pm Addressing Myths Associated with Sex Crimes and Sex Offenders Donna Vandiver, and Jeremy Braithwaite Warwick, 3rd Level<br />

12:30 to 1:50pm Discount or Tax? A Real World Conceptualization of Plea Bargaining Mona Lynch Fulton, 3rd Level<br />

12:30 to 1:50pm The Fair Fight: Contextualizing Procedural Justice in a Veterans Nicole Sherman<br />

Grand Salon 3, 1st Level<br />

Treatment Court<br />

12:30 to 1:50pm Miami Vice: Unpacking the Drug Activity and Neighborhood Violent Christopher Contreras, and John R. Hipp Chequers, 2nd Level<br />

Crime Nexus’<br />

12:30 to 1:50pm Building a Crime Prediction Model: Distinguishing between fast and slow John R. Hipp, and Christopher Jay Bates Chequers, 2nd Level<br />

dynamics over various contexts<br />

12:30 to 1:50pm Living on the Edges: Examining Crime Patterns of Street Segments on Young-An Kim, and John R. Hipp<br />

Chequers, 2nd Level<br />

the Spatial Boundaries<br />

3:30 to 4:50pm Eating Their Own: Police Responses to Excessive Use of Force Peter A. Hanink, Geoff Ward, and Anjuli C. Grand Salon 16, 1st Level<br />

Verma<br />

3:30 to 4:50pm How Rural California Counties Have Been Impacted by California’s Susan Turner<br />

Grand Salon 22, 1st Level<br />

Public Safety Realignment<br />

3:30 to 4:50pm Crook County: Racism and Injustice in America’s Largest Criminal Court Dallas Augustine Chart A, Riverside Complex<br />

5:00 to 6:20pm A Correctional Culture of Masculinity or Survival? Gendered Daniel Scott, Amy M. Magnus, and Cheryl Quarterdeck A, Riverside Complex<br />

Perspectives of Violence Involvement Among Incarcerated Youth Maxson<br />

5:00 to 6:20pm Twenty-Two Years After the Passage of VAWA: A Comparative Case Fei Yang<br />

Bridge, Riverside Complex<br />

Study on Domestic Violence<br />

6:00 to 7:00pm Spatially Diverse Policing: An Examination of Police Typologies across John R. Hipp<br />

Grand Ballroom A, 1st Level<br />

Space and Time<br />

6:00 to 7:00pm Medical Marijuana and Motor Vehicle Fatalities: A Synthetic Control Bradley Bartos, and Richard M. McCleary Grand Ballroom A, 1st Level<br />

Approach to Californias Compassionate Use Act<br />

6:00 to 7:00pm Equality and Inequality in the News: Gender differences in Print Media Kelsey Gushue, Jennifer Wong, and Jason Grand Ballroom A, 1st Level<br />

Portrayal of Homicide Perpetrators<br />

Gravel<br />

6:00 to 7:00pm Predicting Image Inclusion and Image Type in Newspaper Homicide Walter Works, Jennifer Wong, and Jason Gravel Grand Ballroom A, 1st Level<br />

Reports Using Established Crime Reporting Themes<br />

7:15 to 8:15pm Exploring the Relationship Between Airbnb and Neighborhood Crime Michelle D. Mioduszewski, and Christopher Jay Grand Ballroom A, 1st Level<br />

Bates<br />

7:15 to 8:15pm Examining Privileged Drug Use: An Analysis of Congressional Hearings<br />

on Ecstasy<br />

Sofia Laguna<br />

Grand Ballroom A, 1st Level<br />

CLS <strong>Research</strong> <strong>Newsletter</strong> • November 2016 page 8 of 9

Time Title Authors Place<br />

Friday November 18th<br />

8:00 to 9:20am The Internalized Effects of a Criminal Record: The Impact of<br />

Volume 1• Issue 1<br />

November 2016<br />

Dallas Augustine<br />

Jackson, 3rd Level<br />

Incarceration on Job-Seeking and Desistance from Crime after Prison<br />

9:30 to 10:50am Violent Crime and Immigrant Revitalization and Influx in the South: James Bernard Pratt<br />

Grand Salon 3, 1st Level<br />

Contending with a Southern Culture of Violence and Exclusion<br />

9:30 to 10:50am A Tribute to the Scholarship and Spirit of the Late Nicole Hahn Rafter Geoff Ward Port, Riverside Complex<br />

11:00 to 12:20pm The Patterns and Prevalence of Civil Gang Injunctions in the United Alyssa M. Heckmann<br />

Grand Salon 7, 1st Level<br />

States in 2012<br />

11:00 to 12:20pm Crossing Over or Crossing Out America’s Youth? Specialized Courts,<br />

Specialized Justice, and the Realities of Dual-Involvement in the Child<br />

Welfare and Juvenile Delinquency Systems<br />

Amy M. Magnus<br />

Jefferson Ballroom, 3rd Level<br />

11:00 to 12:20pm The Social and Passive Nature of Illegal Gun Transactions in Los<br />

Angeles<br />

George Tita, Keramet Reiter, Natalie A.<br />

Pifer, Jason Gravel, Nicole Sherman, Melissa<br />

Barragan, and Kelsie Chestnut<br />

Elliott Currie<br />

Grand Salon 21, 1st Level<br />

12:30 to 1:50pm Critical <strong>Criminology</strong> in Unjust Times (Organized by Division on Critical<br />

<strong>Criminology</strong>)<br />

Chart A, Riverside Complex<br />

12:30 to 1:50pm The Crime of All Crimes: Toward a <strong>Criminology</strong> of Genocide Geoff Ward Grand Salon 15, 1st Level<br />

2:00 to 3:20pm The Deportability of the Central American Undocumented Community: Jose Alfredo Torres<br />

Grand Salon 4, 1st Level<br />

Immigrant Right Advocates Perceptions, Experiences, and Realities<br />

2:00 to 3:20pm Teaching Race From a Place of Privilege Jaimee Limmer, and Kasey C. Ragan Warwick, 3rd Level<br />

2:00 to 3:20pm Do Uniforms Matter? Experimental Evidence from the Police Officer Rylan Simpson<br />

Grand Ballroom B, 1st Level<br />

Perception Project (POPP)<br />

2:00 to 3:20pm Youth Mobilization and School Criminalization: An Ethnographic Case Analicia Mejia Mesinas<br />

Grand Salon 4, 1st Level<br />

Study of Student Activism in Los Angeles<br />

2:00 to 3:20pm Reclaiming Indigeneity Amongst Chicano Prison Inmates Anna Diaz Villela Grand Salon 4, 1st Level<br />

3:30 to 4:50pm Suicide Rates in Happy Places: Is There a Paradox? Tim Wadsworth, Philip Pendergast, and Charis Jefferson Ballroom, 3rd Level<br />

Kubrin<br />

3:30 to 4:50pm A Replication Study of Police-Involved Homicides Employing Unofficial, Matthew Renner, and Peter A. Hanink<br />

Grand Salon 3, 1st Level<br />

Crowd-Sourced Data<br />

7:00 to 9:00pm University of California, Irvine Reception<br />

River, Riverside Complex<br />

Saturday, November 19th<br />

8:00 to 9:20am Exclusionary Discipline and Neighborhood Crime Julie Gerlinger Quarterdeck C, Riverside Complex<br />

8:00 to 9:20am The Great Experiment: Realigning Criminal Justice in California and Charis Kubrin<br />

Steering, Riverside Complex<br />

Beyond<br />

8:00 to 9:20am The Great Experiment: Realigning Criminal Justice in California and Carroll Seron<br />

Steering, Riverside Complex<br />

Beyond<br />

11:00 to 12:20pm The Threatening Nature of Rap Adam Dunbar, Charis Kubrin, and Nicholas Parish, 3rd Level<br />

Scurich<br />

11:00 to 12:20pm Arts-in-Corrections: Beyond Traditional Rehabilitative Programming Emma Conner, Gabriela Gonzalez, Marina Bell,<br />

and Laura Pecenco<br />

Newberry, 3rd Level<br />

CLS <strong>Research</strong> <strong>Newsletter</strong> • November 2016 page 9 of 9