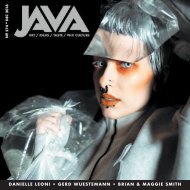

Java.FEB.2017

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

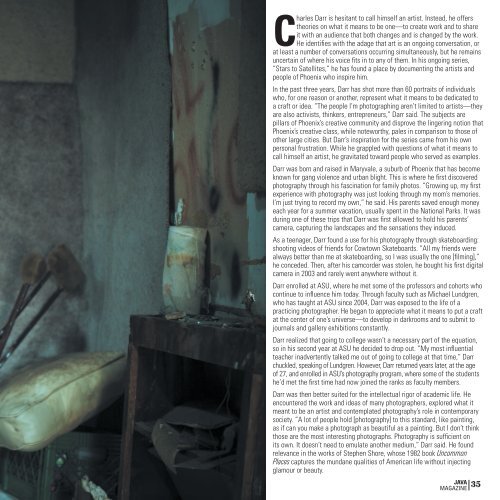

Charles Darr is hesitant to call himself an artist. Instead, he offers<br />

theories on what it means to be one—to create work and to share<br />

it with an audience that both changes and is changed by the work.<br />

He identifies with the adage that art is an ongoing conversation, or<br />

at least a number of conversations occurring simultaneously, but he remains<br />

uncertain of where his voice fits in to any of them. In his ongoing series,<br />

“Stars to Satellites,” he has found a place by documenting the artists and<br />

people of Phoenix who inspire him.<br />

In the past three years, Darr has shot more than 60 portraits of individuals<br />

who, for one reason or another, represent what it means to be dedicated to<br />

a craft or idea. “The people I’m photographing aren’t limited to artists—they<br />

are also activists, thinkers, entrepreneurs,” Darr said. The subjects are<br />

pillars of Phoenix’s creative community and disprove the lingering notion that<br />

Phoenix’s creative class, while noteworthy, pales in comparison to those of<br />

other large cities. But Darr’s inspiration for the series came from his own<br />

personal frustration. While he grappled with questions of what it means to<br />

call himself an artist, he gravitated toward people who served as examples.<br />

Darr was born and raised in Maryvale, a suburb of Phoenix that has become<br />

known for gang violence and urban blight. This is where he first discovered<br />

photography through his fascination for family photos. “Growing up, my first<br />

experience with photography was just looking through my mom’s memories.<br />

I’m just trying to record my own,” he said. His parents saved enough money<br />

each year for a summer vacation, usually spent in the National Parks. It was<br />

during one of these trips that Darr was first allowed to hold his parents’<br />

camera, capturing the landscapes and the sensations they induced.<br />

As a teenager, Darr found a use for his photography through skateboarding:<br />

shooting videos of friends for Cowtown Skateboards. “All my friends were<br />

always better than me at skateboarding, so I was usually the one [filming],”<br />

he conceded. Then, after his camcorder was stolen, he bought his first digital<br />

camera in 2003 and rarely went anywhere without it.<br />

Darr enrolled at ASU, where he met some of the professors and cohorts who<br />

continue to influence him today. Through faculty such as Michael Lundgren,<br />

who has taught at ASU since 2004, Darr was exposed to the life of a<br />

practicing photographer. He began to appreciate what it means to put a craft<br />

at the center of one’s universe—to develop in darkrooms and to submit to<br />

journals and gallery exhibitions constantly.<br />

Darr realized that going to college wasn’t a necessary part of the equation,<br />

so in his second year at ASU he decided to drop out. “My most influential<br />

teacher inadvertently talked me out of going to college at that time,” Darr<br />

chuckled, speaking of Lundgren. However, Darr returned years later, at the age<br />

of 27, and enrolled in ASU’s photography program, where some of the students<br />

he’d met the first time had now joined the ranks as faculty members.<br />

Darr was then better suited for the intellectual rigor of academic life. He<br />

encountered the work and ideas of many photographers, explored what it<br />

meant to be an artist and contemplated photography’s role in contemporary<br />

society. “A lot of people hold [photography] to this standard, like painting,<br />

as if can you make a photograph as beautiful as a painting. But I don’t think<br />

those are the most interesting photographs. Photography is sufficient on<br />

its own. It doesn’t need to emulate another medium,” Darr said. He found<br />

relevance in the works of Stephen Shore, whose 1982 book Uncommon<br />

Places captures the mundane qualities of American life without injecting<br />

glamour or beauty.<br />

JAVA 35<br />

MAGAZINE