International Review of Waste Management Policy - Department of ...

International Review of Waste Management Policy - Department of ...

International Review of Waste Management Policy - Department of ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

<strong>International</strong> <strong>Review</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Waste</strong><br />

<strong>Management</strong> <strong>Policy</strong>:<br />

Annexes to Main Report<br />

Authors:<br />

Eunomia (UK), Tobin Consulting Engineers (Ireland),<br />

Öko-Institute (Germany), Arcadis (Belgium), Scuola<br />

Agraria del Parco di Monza (Italy), TBU Engineering<br />

(Austria), Eunomia New Zealand (New Zealand)<br />

29 th September 2009

Report for:<br />

Mr. Michael Layde, <strong>Department</strong> <strong>of</strong> the Environment, Heritage and Local Government, Ireland<br />

Prepared by:<br />

Dr Dominic Hogg, Dr Adrian Gibbs, Ann Ballinger, Andrew Coulthurst, Tim Elliott, Dr Debbie<br />

Fletcher, Simon Russell, Chris Sherrington, Sam Taylor (Eunomia), Duncan Wilson (Eunomia<br />

New Zealand), Sean Finlay, Damien Grehan, Mairead Hogan, Pat O’Neill (Tobin), Martin<br />

Steiner (TBU), Andreas Hermann, Matthias Buchert (Oko Institut), Ilse Laureysens, Mike van<br />

Acoyleyn (Arcadis), Enzo Favoino and Valentina Caimi (Scuola Agraria del Parco di Monza)<br />

Approved by:<br />

………………………………………………….<br />

Joe Papineschi<br />

(Director)<br />

Contact Details<br />

Eunomia Research & Consulting Ltd<br />

62 Queen Square<br />

Bristol<br />

BS1 4JZ<br />

United Kingdom<br />

Tel: +44 (0)117 9450100<br />

Fax: +44 (0)8717 142942<br />

Web: www.eunomia.co.uk<br />

Acknowledgements<br />

We are grateful to the Steering Group for this project and to those who contributed to the<br />

Consultative Group meetings. Several organisations also made submissions in writing and we<br />

are very grateful to them for the time spent doing so, and the insights provided.<br />

Disclaimer<br />

Eunomia Research & Consulting has taken due care in the preparation <strong>of</strong> this document to<br />

ensure that all facts and analysis presented are as accurate as possible within the scope <strong>of</strong><br />

the project. However Eunomia makes no warranty, express or implied, with respect to the use<br />

<strong>of</strong> any information disclosed in this document, or assumes any liabilities with respect to the<br />

use <strong>of</strong>, or damage resulting in any way from the use <strong>of</strong> any information disclosed in this<br />

document.<br />

<strong>International</strong> <strong>Review</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Waste</strong> <strong>Policy</strong>: Annexes

29/09/09

Contents<br />

WASTE WASTE POLICIES POLICIES POLICIES – EXISTING EXISTING FRAMEWORK FRAMEWORK AND AND SOME SOME THEORETICAL THEORETICAL CONSIDERATIONS<br />

CONSIDERATIONS.......<br />

CONSIDERATIONS ....... 1<br />

i<br />

1.0 <strong>Waste</strong> Policies – a <strong>Review</strong> <strong>of</strong> the Existing Framework .....................................................2<br />

2.0 <strong>Policy</strong> Instruments for <strong>Waste</strong> <strong>Management</strong>....................................................................31<br />

KEY KEY KEY INSTITUTIONAL INSTITUTIONAL INSTITUTIONAL ISSUES ISSUES................................<br />

ISSUES ISSUES................................<br />

................................................................<br />

................................ ................................<br />

................................................................<br />

................................ ................................<br />

......................................<br />

................................ ...... ......42 ...... 42 42<br />

3.0 Competition in the Market for <strong>Waste</strong> Collection.............................................................44<br />

4.0 The Role <strong>of</strong> Local Authorities............................................................................................63<br />

5.0 Governance Structures / Responsibilities for Delivery <strong>of</strong> National Strategy ................74<br />

POLICIES POLICIES POLICIES FOR FOR FOR MUNICIPAL MUNICIPAL MUNICIPAL WASTE WASTE................................<br />

WASTE WASTE................................<br />

................................................................<br />

................................ ................................<br />

.............................................................<br />

................................ .............................<br />

.............................84<br />

............................. 84 84<br />

6.0 <strong>Review</strong> <strong>of</strong> Irish <strong>Policy</strong> on Prevention and Recycling........................................................85<br />

7.0 Pay-By-Use - Ireland ....................................................................................................... 103<br />

8.0 Pay-by-use - <strong>International</strong> .............................................................................................. 118<br />

9.0 Pay-by-use – Germany ................................................................................................... 159<br />

10.0 Pay-by-use – Flanders, Belgium................................................................................. 176<br />

11.0 Landfill Levy - Ireland.................................................................................................. 185<br />

12.0 Producer Responsibility, Packaging - Ireland............................................................ 199<br />

13.0 Producer Responsibility, Packaging - <strong>International</strong>.................................................. 229<br />

14.0 Producer Responsibility, Packaging - Germany ........................................................ 253<br />

15.0 Producer Responsibility – Flanders, Belgium........................................................... 263<br />

16.0 Deposit Refund Systems - <strong>International</strong> ................................................................... 297<br />

17.0 Deposit Refund Scheme - Germany .......................................................................... 340<br />

18.0 National <strong>Waste</strong> Prevention Programme - Ireland ..................................................... 350<br />

19.0 Producer Responsibility, WEEE - Ireland................................................................... 362<br />

20.0 Producer Responsibility, WEEE - <strong>International</strong> ......................................................... 376<br />

21.0 Producer Responsibility, WEEE - Germany................................................................ 406<br />

22.0 Producer Responsibility, ELVs - Ireland..................................................................... 417<br />

23.0 Producer Responsibility, ELVs - <strong>International</strong>........................................................... 431<br />

24.0 Producer Responsibility, Batteries - Ireland.............................................................. 448<br />

25.0 Producer Responsibility, Batteries - <strong>International</strong>.................................................... 457<br />

26.0 Producer Responsibility, Batteries - Germany .......................................................... 478<br />

27.0 Plastic Bag Levy - Ireland ........................................................................................... 487<br />

28.0 Packaging Taxes - <strong>International</strong>................................................................................. 498<br />

29.0 Tyre Charge - <strong>International</strong>......................................................................................... 508<br />

30.0 Product Taxes - Belgium............................................................................................. 515<br />

31.0 Plastic Bag Bans – <strong>International</strong> ............................................................................... 525<br />

<strong>International</strong> <strong>Review</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Waste</strong> <strong>Policy</strong>: Annexes

ii<br />

32.0 Levy on <strong>Waste</strong> Paints - <strong>International</strong>......................................................................... 529<br />

33.0 Circular WPPR 17/08 - Ireland .................................................................................. 533<br />

34.0 Minimum Recycling Standards (Household <strong>Waste</strong>) - <strong>International</strong>......................... 543<br />

35.0 Minimum Recycling Standards (Commercial and Industrial <strong>Waste</strong>) - <strong>International</strong><br />

564<br />

36.0 Product Standards: Biowaste Treatment Products - <strong>International</strong>.......................... 570<br />

37.0 Animal By–Products Regulations – Ireland .............................................................. 588<br />

38.0 Policies For Dealing With Junk Mail........................................................................... 598<br />

CONSTRUCTION CONSTRUCTION CONSTRUCTION AND AND AND DEMOLITION DEMOLITION DEMOLITION WASTE WASTE................................<br />

WASTE WASTE................................<br />

................................................................<br />

................................ ................................<br />

.............................................<br />

................................ ............. .............604<br />

............. 604 604<br />

39.0 <strong>Review</strong> <strong>of</strong> Irish <strong>Policy</strong>, Construction & Demolition <strong>Waste</strong> ........................................ 605<br />

40.0 National Construction and Demolition <strong>Waste</strong> Council - Ireland .............................. 608<br />

41.0 Landfill Levy - Ireland.................................................................................................. 616<br />

42.0 C & D <strong>Waste</strong> <strong>Management</strong> Plan Guidelines - Ireland............................................... 626<br />

43.0 Site <strong>Waste</strong> <strong>Management</strong> Plans - <strong>International</strong> ......................................................... 632<br />

44.0 <strong>Waste</strong> Facility Permit Regulations - Ireland .............................................................. 644<br />

45.0 Demolition Protocol - UK ............................................................................................ 650<br />

46.0 Tax on Aggregates - <strong>International</strong> .............................................................................. 653<br />

47.0 Product Standards for Aggregates - <strong>International</strong> .................................................... 667<br />

48.0 Minimum Recycling Standards (Construction and Demolition <strong>Waste</strong>) - <strong>International</strong><br />

673<br />

49.0 Incentives Affecting Construction and Demolition <strong>Waste</strong> - Belgium ....................... 690<br />

50.0 Minimum Recycling Standards (Construction and Demolition <strong>Waste</strong>) - Germany. 691<br />

POLICIES POLICIES FOR FOR RESIDUAL RESIDUAL WASTE WASTE ................................<br />

................................................................<br />

................................<br />

................................<br />

............................................................<br />

................................ ............................<br />

............................693<br />

............................ 693<br />

51.0 The Landfill Directive – Current Situation................................................................. 694<br />

52.0 Policies Aimed at Discouraging Disposal .................................................................. 727<br />

53.0 Landfill Ban (German Case Study)............................................................................. 794<br />

54.0 <strong>Waste</strong> Levies and Bans (Belgium-Flanders Case Study) ......................................... 800<br />

55.0 Landfill Allowance Schemes (UK) .............................................................................. 808<br />

56.0 Proposed <strong>Policy</strong> Changes ........................................................................................... 824<br />

OTHER OTHER POLICIES POLICIES................................<br />

POLICIES POLICIES................................<br />

................................................................<br />

................................ ................................<br />

................................................................<br />

................................ ................................<br />

......................................................<br />

................................ ......................<br />

......................845<br />

...................... 845 845<br />

57.0 Green Public Procurement ......................................................................................... 846<br />

58.0 Ireland and the UNECE / Stockholm Conventions ................................................... 862<br />

TARGET TARGET SETTING SETTING................................<br />

SETTING SETTING................................<br />

................................................................<br />

................................ ................................<br />

................................................................<br />

................................ ................................<br />

.....................................................<br />

................................ .....................<br />

.....................867<br />

..................... 867<br />

59.0 Target Setting.............................................................................................................. 868<br />

GRANT GRANT GRANT FUNDING FUNDING................................<br />

................................................................<br />

................................ ................................<br />

................................................................<br />

................................ ................................<br />

.....................................................<br />

................................ .....................<br />

.....................901<br />

..................... 901<br />

60.0 Grant Funding ............................................................................................................. 902<br />

29/09/09

TECHNICAL TECHNICAL ANNEXES ANNEXES................................<br />

ANNEXES ANNEXES................................<br />

................................................................<br />

................................ ................................<br />

................................................................<br />

................................ ................................<br />

.............................................<br />

................................ ............. ............. 930 930<br />

930<br />

iii<br />

61.0 Appraisal <strong>of</strong> Residual <strong>Waste</strong> Treatment Options...................................................... 931<br />

62.0 Life-cycle Assessment <strong>of</strong> Residual <strong>Waste</strong> Treatment Technologies ....................... 964<br />

63.0 Externalities <strong>of</strong> <strong>Waste</strong> <strong>Management</strong> Options ........................................................... 978<br />

64.0 Costs <strong>of</strong> Household <strong>Waste</strong> Collection .....................................................................1033<br />

<strong>International</strong> <strong>Review</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Waste</strong> <strong>Policy</strong>: Annexes

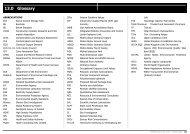

Glossary <strong>of</strong> Acronyms<br />

iv<br />

29/09/09<br />

ABP Belgian Pharmaceutical Association<br />

ADF Advanced disposal fee<br />

AOO Netherlands <strong>Waste</strong> <strong>Management</strong> Council<br />

ARF Advance recycling fees<br />

AVGI Belgian Pharmaceutical Industry Association<br />

B2C Business to consumer<br />

B2B Business to business<br />

BAT Best available techniques<br />

BDMV Belgian Direct Marketing Association<br />

BEBAT Belgian producer responsibility organisation for batteries<br />

BMW Biodegradable municipal waste<br />

BPF Belgian Petrol Federation<br />

BVDU Belgian Association <strong>of</strong> Publishers<br />

C&D Construction and demolition (wastes)<br />

C&I Commercial and industrial (wastes)<br />

CA sites/CAS Civic Amenity Sites<br />

CARE Carpet America Recovery Effort<br />

CCMA City and County Managers Association<br />

CEN European Committee for Standardisation<br />

CIF Construction Industry Federation<br />

CLRTAP Convention on Long-range Transboundary Air Pollution<br />

COP4 Fourth Conference <strong>of</strong> the Parties<br />

CPI Consumer Price Index<br />

CPT Core Prevention Team<br />

Cre Composting Association Ireland<br />

CRT Cathode ray tube<br />

DAFF <strong>Department</strong> for Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry<br />

DIFTAR Differentiated tariffs (pay-by-use)<br />

DfE Design for the Environment<br />

DGRNE-OWD Wallonian Directorate General for Natural Resources and<br />

Environment - Wallonian Office for <strong>Waste</strong><br />

DoEHLG <strong>Department</strong> <strong>of</strong> Environment, Heritage and Local Government<br />

DPG Deutsche Pfandsystem GmbH

v<br />

DSD Duales System Deutschland<br />

DVC Differential and variable charging (pay-by-use)<br />

DVR Differential and variable rate charging (pay-by-use)<br />

EEA European Environment Agency<br />

EfW Energy from waste<br />

ELVs End <strong>of</strong> life vehicles<br />

EMAS Eco-management and Audit Scheme<br />

EPA Environmental Protection Agency<br />

EPR Extended producer responsibility<br />

ESRI Economic and Social Research Institute<br />

EWC European <strong>Waste</strong> Catalogue<br />

FEBELAUTO Belgian confederation gathering the different groupings <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Belgian automotive sector<br />

FEBELGEN Generic pharmaceutical organisation<br />

FEBELGRA Federation <strong>of</strong> the Belgian printing and communication industry<br />

FEDIS Belgian federation <strong>of</strong> distributors<br />

GDP Gross Domestic Product<br />

GHG Greenhouse Gas<br />

HCB Hexachlorobenzene<br />

Hhld Household<br />

IBEC The Irish Business and Employers Confederation<br />

ISO 14001 Environmental management systems<br />

IWMA Irish <strong>Waste</strong> <strong>Management</strong> Association<br />

JCPRA Japan Containers and Packaging Recycling Association<br />

JRC Joint Research Centre (European Commission)<br />

LA Local authority<br />

LAB Association Belgium<br />

LCA Life cycle assessment<br />

MBO Milieubeleidsovereenkomst-environmental policy agreements<br />

with producers<br />

MBT Mechanical biological treatment<br />

MDG Market Development Group<br />

MPC Marginal private costs<br />

MRF Materials recovery facility<br />

MS (EU) Member State<br />

MSC Marginal social costs<br />

<strong>International</strong> <strong>Review</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Waste</strong> <strong>Policy</strong>: Annexes

vi<br />

29/09/09<br />

MSW Municipal solid waste<br />

NAVETEX National Association <strong>of</strong> Textile Retailers<br />

NBWS National biodegradable waste strategy<br />

NGO Non-governmental organization<br />

NFIW National Association <strong>of</strong> Informative Magazines<br />

NIR Near infrared<br />

NVGV National Organisation <strong>of</strong> Pharmaceutical Wholesalers<br />

Octa BDE’ Octa-brominated diphenyl ether<br />

OECD Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development<br />

OEE Office <strong>of</strong> Environmental Enforcement<br />

OFBMW Organic fraction <strong>of</strong> biodegradable municipal waste<br />

OPHACO Belgian Association <strong>of</strong> Pharmaceutical Cooperatives<br />

OVAM The Public Flemish <strong>Waste</strong> Agency<br />

PAHs Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons<br />

PAYT Pay-as-you-throw (pay-by-use)<br />

PBU Pay-by-use<br />

PBUC Pay by use charge<br />

PCBs Polychlorinated biphenyls<br />

Penta BDE’ Penta brominated diphenyl ether<br />

PERN Packaging export recovery note<br />

PET Polyethylene terephthalate<br />

PMD Plastiek, Metaal en Drankverpakkingen (packaging made <strong>of</strong><br />

plastic, metal and drinks cartons)<br />

PPP Public private partnership<br />

POPs Persistent organic pollutants<br />

PRN Packaging recovery note<br />

PRO Producer responsibility organisation<br />

R&D Research and development<br />

RBRC Rechargeable Battery Recycling Corporation<br />

RECUPEL Flemish producer responsibility organisation dealing with waste<br />

electrical and electronic equipment<br />

RECYBAT Flemish producer responsibility organisation dealing with<br />

accumulators.<br />

RIA Regulatory impact assessment<br />

RPS Repak payment system<br />

RWMPs Regional waste management plans

vii<br />

SNIFFER Scotland and Northern Ireland Forum for Environmental Research<br />

UUPP <strong>International</strong> Federation <strong>of</strong> Periodical Press<br />

UN-ECE United Nations Economic Commission for Europe<br />

WEEE <strong>Waste</strong> electrical and electronic equipment<br />

WFD <strong>Waste</strong> framework directive<br />

WFL <strong>Waste</strong> facility levy<br />

WID <strong>Waste</strong> incineration directive<br />

WRAP <strong>Waste</strong> and Resources Action Programme (UK)<br />

VALORLUB Belgian producer responsibility organisation dealing with waste<br />

oils<br />

VDV Association <strong>of</strong> food retailers<br />

VEGRAB Federation <strong>of</strong> printing companies<br />

VLACO The Flemish organisation for promoting composting and compost<br />

use<br />

VLAREA Flemish regulation for waste<br />

VFG Vegetable, fruit and garden (biowaste)<br />

VROM The Netherlands Ministry <strong>of</strong> Housing, Spatial Planning and the<br />

Environment<br />

VUKPP Federation <strong>of</strong> Catholic Periodical Press<br />

<strong>International</strong> <strong>Review</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Waste</strong> <strong>Policy</strong>: Annexes

WASTE POLICIES – EXISTING FRAMEWORK AND<br />

SOME THEORETICAL CONSIDERATIONS<br />

1<br />

<strong>International</strong> <strong>Review</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Waste</strong> <strong>Policy</strong>: Annexes

1.0 <strong>Waste</strong> Policies – a <strong>Review</strong> <strong>of</strong> the Existing<br />

Framework<br />

Irish waste management has made enormous strides over the past decade. The<br />

statistics tell a story <strong>of</strong> impressive improvements in performance in many areas,<br />

whilst some <strong>of</strong> the improvements are not so readily revealed though appeal to<br />

statistics alone (for example, with regard to the effects <strong>of</strong> closing down old ‘dumps’<br />

which posed a threat to the environment).<br />

The changes which Ireland has made have been, to a considerable degree, motivated<br />

by policies emanating from Europe. Much focus tends to fall upon the so-called<br />

Producer Responsibility Directives in this regard, yet the impact <strong>of</strong> changes to the<br />

operation and regulation <strong>of</strong> landfills has also been significant. This has increased the<br />

costs <strong>of</strong> disposal, and thereby increased the benefits associated with avoiding<br />

disposal (through prevention, re-use, recycling and alternative treatments). Recycling,<br />

in particular, is likely to have been incentivised by the escalation in landfill gate fees.<br />

In this Annex, we outline what we believe to be the salient issues in respect <strong>of</strong><br />

European waste policy and legislation as it affects Ireland. It would not be possible to<br />

look at each and every aspect <strong>of</strong> each piece <strong>of</strong> policy. The overview is unashamedly<br />

forward-looking. It looks to the future with a view to understanding the challenges<br />

ahead, rather than seeking to dwell on past achievements.<br />

1.1 The Priority Status <strong>of</strong> <strong>Waste</strong> Prevention<br />

As is well known, waste prevention lies at the top <strong>of</strong> the waste management<br />

hierarchy. The status <strong>of</strong> waste prevention in this respect has been reinforced by the<br />

revised <strong>Waste</strong> Framework Directive (WFD) under Article 4: 1<br />

2<br />

29/09/09<br />

“1. The following waste hierarchy shall apply as a priority order in waste<br />

prevention and management legislation and policy:<br />

a) prevention;<br />

b) preparing for re-use;<br />

c) recycling;<br />

d) other recovery, e.g. energy recovery; and<br />

e) disposal.<br />

2. When applying the waste hierarchy referred to in paragraph 1, Member<br />

States shall take measures to encourage the options that deliver the best<br />

overall environmental outcome. This may require specific waste streams<br />

1 Directive 2008/98/EC <strong>of</strong> the European Parliament and the Council <strong>of</strong> 19 November 2008 on <strong>Waste</strong><br />

and Repealing Certain Directives.

3<br />

departing from the hierarchy where this is justified by life-cycle thinking on the<br />

overall impacts <strong>of</strong> the generation and management <strong>of</strong> such waste.<br />

Member States shall ensure that the development <strong>of</strong> waste legislation and<br />

policy is a fully transparent process, observing existing national rules about<br />

the consultation and involvement <strong>of</strong> citizens and stakeholders.<br />

Member States shall take into account the general environmental protection<br />

principles <strong>of</strong> precaution and sustainability, technical feasibility and economic<br />

viability, protection <strong>of</strong> resources as well as the overall environmental, human<br />

health, economic and social impacts, in accordance with Articles 1 and 13.”<br />

The above suggests that other than where life-cycle thinking suggests otherwise,<br />

prevention and preparing for re-use should be considered priority areas for waste<br />

management policy in future. Indeed, the WFD sets out a requirement for Member<br />

States to develop <strong>Waste</strong> Prevention Programmes under Articles 29 to 31: 2<br />

“Article Article 29<br />

<strong>Waste</strong> prevention programmes<br />

1. Member States shall establish, in accordance with Articles 1 and 4, 4, 4, waste<br />

prevention programmes not later than [five years and 20 days after<br />

publication <strong>of</strong> the WFD in the Official Journal].<br />

Such programmes shall be integrated either into the waste management<br />

plans provided for in Article 28 or into other environmental policy<br />

programmes, as appropriate, or shall function as separate programmes. If any<br />

such programme is integrated into the waste management plan or into other<br />

programmes, the waste prevention measures shall be clearly identified.<br />

2. The programmes provided for in paragraph 1 shall set out the waste<br />

prevention objectives Member States shall describe the existing prevention<br />

measures and evaluate the usefulness <strong>of</strong> the examples <strong>of</strong> measures indicated<br />

in Annex IV or other appropriate measures.<br />

The aim <strong>of</strong> such objectives and measures shall be to break the link between<br />

economic growth and the environmental impacts associated with the<br />

generation <strong>of</strong> waste.<br />

3. Member States shall determine appropriate specific qualitative or<br />

quantitative benchmarks for waste prevention measures adopted in order to<br />

monitor and assess the progress <strong>of</strong> the measures and may determine specific<br />

qualitative or quantitative targets and indicators, other than those referred to<br />

in paragraph 4, for the same purpose.<br />

4. Indicators for waste prevention measures may be adopted in accordance<br />

with the procedure referred to in Article 39 (3).<br />

2 Directive 2008/98/EC <strong>of</strong> the European Parliament and the Council <strong>of</strong> 19 November 2008 on <strong>Waste</strong><br />

and Repealing Certain Directives.<br />

<strong>International</strong> <strong>Review</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Waste</strong> <strong>Policy</strong>: Annexes

4<br />

29/09/09<br />

5. The Commission shall create create create a a a system system system for for for sharing sharing sharing information information on on best best<br />

practice practice regarding regarding waste waste pre prevention pre pre vention and and develop guidelines in order to assist<br />

the Member States in the preparation <strong>of</strong> the Programmes. 3<br />

Article Article 30<br />

30<br />

Evaluation and review <strong>of</strong> plans and programmes<br />

1. 1. Member States shall ensure that the waste management plans and waste<br />

prevention programmes are evaluated at least every sixth year and revised as<br />

appropriate and, where relevant, in accordance with Articles 9 and 11 .<br />

2. The European Environment Agency is invited to include in its annual report<br />

a review <strong>of</strong> progress in the completion and implementation <strong>of</strong> waste<br />

prevention programmes.<br />

Article Article 31<br />

31<br />

Public participation<br />

Member States shall ensure that relevant stakeholders and authorities and<br />

the general public have the opportunity to participate in the elaboration <strong>of</strong> the<br />

waste management plans and waste prevention programmes, and have<br />

access to them once elaborated, in accordance with Directive 2003/35/EC<br />

or, if relevant, Directive 2001/42/EC <strong>of</strong> the European Parliament and <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Council <strong>of</strong> 27 June 2001 on the assessment <strong>of</strong> the effects <strong>of</strong> certain plans<br />

and programmes on the environment. They shall place the plans and<br />

programmes on a publicly available website.”<br />

The measures referred to in Article 29 as being set out in Annex IV are shown in Box 1<br />

below. 4<br />

Box 1: Annex IV <strong>of</strong> the WFD<br />

Examples <strong>of</strong> waste prevention measures referred to in Article 29<br />

Measures that can affect the framework conditions related to the generation <strong>of</strong> waste<br />

1. The use <strong>of</strong> planning measures, or other economic instruments promoting the efficient use <strong>of</strong> resources.<br />

2. The promotion <strong>of</strong> research and development into the area <strong>of</strong> achieving cleaner and less wasteful products<br />

and technologies and the dissemination and use <strong>of</strong> the results <strong>of</strong> such research and development.<br />

3. The development <strong>of</strong> effective and meaningful indicators <strong>of</strong> the environmental pressures associated with<br />

the generation <strong>of</strong> waste aimed at contributing to the prevention <strong>of</strong> waste generation at all levels, from product<br />

comparisons at Community level through action by local authorities to national measures.<br />

Measures that can affect the design and production and distribution phase<br />

4. The promotion <strong>of</strong> eco-design (the systematic integration <strong>of</strong> environmental aspects into product design with<br />

the aim to improve the environmental performance <strong>of</strong> the product throughout its whole life cycle).<br />

5. The provision <strong>of</strong> information on waste prevention techniques with a view to facilitating the implementation<br />

<strong>of</strong> best available techniques by industry.<br />

6. Organise training <strong>of</strong> competent authorities as regards the insertion <strong>of</strong> waste prevention requirements in<br />

permits under this Directive and Directive 96/61/EC.<br />

3 The European Commission has already initiated the process <strong>of</strong> developing these Guidelines.<br />

4 Directive 2008/98/EC <strong>of</strong> the European Parliament and the Council <strong>of</strong> 19 November 2008 on <strong>Waste</strong><br />

and Repealing Certain Directives.

7. The inclusion <strong>of</strong> measures to prevent waste production at installations not falling under Directive 96/61/EC.<br />

Where appropriate, such measures could include waste prevention assessments or plans.<br />

8. The use <strong>of</strong> awareness campaigns or the provision <strong>of</strong> financial, decision making or other support to<br />

businesses. Such measures are likely to be particularly effective where they are aimed at, and adapted to,<br />

small and medium sized enterprises and work through established business networks.<br />

9. The use <strong>of</strong> voluntary agreements, consumer/producer panels or sectoral negotiations in order that the<br />

relevant businesses or industrial sectors set their own waste prevention plans or objectives or correct<br />

wasteful products or packaging.<br />

10. The promotion <strong>of</strong> creditable environmental management systems, including EMAS and ISO 14001.<br />

Measures that can affect the consumption and use phase<br />

11. Economic instruments such as incentives for clean purchases or the institution <strong>of</strong> an obligatory payment<br />

by consumers for a given article or element <strong>of</strong> packaging that would otherwise be provided free <strong>of</strong> charge.<br />

12. The use <strong>of</strong> awareness campaigns and information provision directed at the general public or a specific<br />

set <strong>of</strong> consumers.<br />

13. The promotion <strong>of</strong> creditable eco-labels.<br />

14. Agreements with industry, such as the use <strong>of</strong> product panels such as those being carried out within the<br />

framework <strong>of</strong> Integrated Product Policies or with retailers on the availability <strong>of</strong> waste prevention information<br />

and products with a lower environmental impact.<br />

15. In the context <strong>of</strong> public and corporate procurement, the integration <strong>of</strong> environmental and waste<br />

prevention criteria into calls for tenders and contracts, in line with the Handbook on environmental public<br />

procurement published by the Commission on 29 October 2004.<br />

16. The promotion <strong>of</strong> the reuse and/or repair <strong>of</strong> appropriate discarded products or <strong>of</strong> their components,<br />

notably through the use <strong>of</strong> educational, economic, logistic or other measures such as support to or<br />

establishment <strong>of</strong> accredited repair and reuse-centres and networks especially in densely populated regions.<br />

It is clear from the above – the position <strong>of</strong> waste prevention in the hierarchy, and the<br />

need to develop waste prevention programmes, both flowing from the revised WFD –<br />

that waste prevention is beginning to attract growing attention as an area that needs<br />

to be tackled by policy makers. The concept <strong>of</strong> ‘decoupling’ the level <strong>of</strong> activity in the<br />

economy from the level <strong>of</strong> waste being generated is a prominent one, and reflects<br />

concerns that economic growth is not yet on what might be considered to be a<br />

sustainable trajectory. To this end, the WFD includes provision, under Article 9, for<br />

decoupling objectives to be set: 5<br />

5<br />

“The Commission shall, following the consultation <strong>of</strong> stakeholders, submit to<br />

the European Parliament and the Council the following reports accompanied,<br />

if appropriate, by proposals for measures required in support <strong>of</strong> the prevention<br />

activities and the implementation <strong>of</strong> the waste prevention programmes<br />

referred to in Article 29 covering:<br />

a) by the end <strong>of</strong> 2011 an interim report on the evolution <strong>of</strong> waste generation<br />

and the scope <strong>of</strong> waste prevention;<br />

(aa) by the end <strong>of</strong> 2011 the formulation <strong>of</strong> a product eco-design policy<br />

addressing both the generation <strong>of</strong> waste and the presence <strong>of</strong> hazardous<br />

substances in waste, with a view to promoting technologies focusing on<br />

durable, re-usable and recyclable products;<br />

5 Directive 2008/98/EC <strong>of</strong> the European Parliament and the Council <strong>of</strong> 19 November 2008 on <strong>Waste</strong><br />

and Repealing Certain Directives.<br />

<strong>International</strong> <strong>Review</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Waste</strong> <strong>Policy</strong>: Annexes

6<br />

29/09/09<br />

b) by by by the the the end end end <strong>of</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>of</strong> 2014 2014 2014 the the the setting setting setting <strong>of</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>of</strong> waste waste waste prev prevention prev prevention<br />

ention and and and decoupling decoupling<br />

decoupling<br />

objectives objectives for for 2020, 2020, based based on on on best best available available practices practices including, including, including, if if necessary,<br />

necessary,<br />

a a revision revision <strong>of</strong> <strong>of</strong> the the indicators indicators referred referred to to in in Article Article 29(4) 29(4); 29(4)<br />

c) by the end <strong>of</strong> 2011 the formulation <strong>of</strong> an action plan for further support<br />

measures at European level seeking in particular to change the current<br />

consumption patterns.”<br />

Evidently, if Irish policy and strategy development is to be future-pro<strong>of</strong>ed, the issue <strong>of</strong><br />

waste prevention and decoupling waste generation from economic growth needs to<br />

be considered.<br />

1.2 Definitions<br />

The definition <strong>of</strong> ‘prevention’ has been a matter <strong>of</strong> some debate. The OECD defines<br />

waste prevention as covering the top three elements <strong>of</strong> the standard waste hierarchy,<br />

describing these as: 6<br />

� Strict Strict Strict avoidance avoidance avoidance - the complete prevention <strong>of</strong> waste generation by virtual<br />

elimination <strong>of</strong> hazardous substances or by reducing material or energy<br />

intensity in production, consumption, and distribution.<br />

� Reduction Reduction Reduction at at source source - minimising use <strong>of</strong> toxic or harmful substances and/or<br />

minimising material or energy consumption.<br />

� Product Product Product re re-use re use use - the multiple use <strong>of</strong> a product in its original form, for its original<br />

purpose or for an alternative, with or without reconditioning.<br />

Other studies expand on this definition to include the following examples: 7<br />

“Household waste prevention is minimising the quantity (weight and volume)<br />

and hazardousness <strong>of</strong> household-derived waste generated in a defined<br />

community for collection by any party.<br />

The following activities are included:<br />

Avoidance;<br />

Avoidance;<br />

for example by eliminating hazardous components and substances, by<br />

not purchasing unnecessary goods, by buying services or experiences<br />

rather than goods, by using refill systems and by preventing delivery <strong>of</strong><br />

unwanted mail.<br />

Reduction;<br />

Reduction;<br />

for example by buying less hazardous goods, by purchasing less heavily<br />

packaged goods and goods that are lighter, more compact and more<br />

durable.<br />

6 OECD (2000) Strategic <strong>Waste</strong> Prevention: OECD Reference Manual, Paris: OECD<br />

7 Enviros and Momenta (2005) Towards a UK Framework for Household <strong>Waste</strong> Prevention, Phase 1<br />

Report for the National Resources & <strong>Waste</strong> Forum.

7<br />

Reuse; Reuse;<br />

Reuse;<br />

for example domestic reuse <strong>of</strong> containers, donation <strong>of</strong> goods to<br />

charities, refurbishment and reuse <strong>of</strong> goods (not-for-pr<strong>of</strong>it or<br />

commercially), home and community composting.”<br />

Centralised composting and energy recovery were excluded, but home composting<br />

was included.<br />

These definitions might be considered, for the purposes <strong>of</strong> developing Irish policy, to<br />

have been superseded by what has now been agreed in the new <strong>Waste</strong> Framework<br />

Directive (WFD). Article 3 sets out the following Definitions <strong>of</strong> relevance to ‘waste<br />

prevention’: 8<br />

"‘Prevention’ means measures taken before a substance, material or product<br />

has become waste, that reduce:<br />

(a) the quantity <strong>of</strong> waste, including through the re-use <strong>of</strong> products or the<br />

extension <strong>of</strong> life-span <strong>of</strong> products;<br />

(b) the adverse impacts <strong>of</strong> the generated waste on the environment and<br />

human health; or<br />

(c) the content <strong>of</strong> harmful substances in materials and products;”<br />

Since prevention includes re-use:<br />

"‘Re-use’ means any operation by which products or components that are not<br />

waste are used again for the same purpose for which they were conceived;<br />

‘Preparing for re-use’ means checking, cleaning or repairing recovery<br />

operations, by which products or components <strong>of</strong> products that have become<br />

waste are prepared so that they will be re-used without any other preprocessing;”<br />

Given that Ireland will have to align its legislation with these requirements, it seems<br />

only logical to use the definitions set out in the revised WFD.<br />

It is, <strong>of</strong> course, important to note that a reduction in waste collected by a local<br />

authority does not necessarily imply that ‘waste prevention’ has occurred to an<br />

equivalent degree (for example, where waste is dumped or burnt illegally).<br />

One <strong>of</strong> the previous debates within the context <strong>of</strong> waste prevention related to how<br />

one should consider measures which reduce the hazardousness <strong>of</strong> waste through<br />

increasing the quantity <strong>of</strong> waste (for example, using vitrification, or stabilisation in<br />

cement). The Commission’s definition appears to address this by including the clause<br />

‘measures taken before a substance, material or product has become waste’ In other<br />

words, measures which reduce hazardousness after a waste has been generated<br />

would not be considered ‘waste prevention’.<br />

8 Directive 2008/98/EC <strong>of</strong> the European Parliament and the Council <strong>of</strong> 19 November 2008 on <strong>Waste</strong><br />

and Repealing Certain Directives.<br />

<strong>International</strong> <strong>Review</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Waste</strong> <strong>Policy</strong>: Annexes

1.3 <strong>Waste</strong> Prevention <strong>Policy</strong> – Links to Measurement <strong>of</strong> Success<br />

Our experience <strong>of</strong> assessing waste prevention policy is that the almost universally<br />

agreed ‘priority status’ given to waste prevention, reflected in its place at the top <strong>of</strong><br />

the waste hierarchy, is not reflected in the way policy has been developed. Most <strong>of</strong><br />

the influential policies that are addressed to ‘waste’ are not designed to address<br />

waste prevention directly. Rather, they seek to reduce the quantity <strong>of</strong> waste disposed,<br />

or increase its recycling, and sometimes, its recovery. This experience is reinforced in<br />

the review <strong>of</strong> policy undertaken within this report. As regards policies, waste<br />

prevention has not been given the status it deserves. This may be a reflection <strong>of</strong> the<br />

fact that waste policy is influenced by those associated with the management <strong>of</strong><br />

waste. <strong>Waste</strong> prevention is clearly an activity that diminishes the activity <strong>of</strong> those<br />

involved in ‘managing waste’.<br />

The negotiations around the WFD itself included debates around waste prevention<br />

targets and whether they should be set in the WFD. Notwithstanding the clear<br />

agreement on the place <strong>of</strong> waste prevention at the top <strong>of</strong> the hierarchy, policy<br />

makers’ commitment to establishing targets for this is clearly somewhat weak. The<br />

usual argument, rarely challenged (and hence, even more rarely requiring a sensible<br />

defence) is that waste prevention is ‘not measurable’ because one is seeking to<br />

measure ‘something which is no longer there’.<br />

This absence <strong>of</strong> imagination and creativity in the quest to understand how one might<br />

measure waste prevention perhaps explains, in part, the absence <strong>of</strong> relevant policies<br />

themselves. There is an urgent need, therefore, for more cool-headed and creative<br />

thinking about:<br />

8<br />

1. Indicators for measuring success <strong>of</strong> a programme <strong>of</strong> waste prevention; and<br />

2. Means to evaluate the contribution <strong>of</strong> specific measures.<br />

In the case <strong>of</strong> the former, some discussion is provided below. In the case <strong>of</strong> the latter,<br />

it seems entirely likely that the approach has to be tailored to fit the policy. Otherwise,<br />

similar rules and guidelines apply as for any ex post assessment <strong>of</strong> any policy. Just<br />

because a policy refers to ‘waste prevention’, this does not mean that the only way to<br />

evaluate its effectiveness is to measure ‘what is no longer there’. As with all ex post<br />

evaluations, the real issue relates to devising a mechanism to evaluate the policy<br />

against a relevant counterfactual scenario. ‘What is no longer there’ is then estimated<br />

‘by subtraction’ using the situation as it now stands, and the situation as it would<br />

have been without the policy in place.<br />

1.3.1 Measuring Decoupling<br />

Prevention policies are typically responses to observed pressures, and require<br />

indicators to measure the success <strong>of</strong> the policy in terms <strong>of</strong> the response. There are<br />

different strategies open to understand the impact <strong>of</strong> the policy. However, what is<br />

essential is to understand the link between changes in waste quantities /<br />

hazardousness <strong>of</strong> waste and the policy itself.<br />

Decoupling means that the link between economic growth and the growth <strong>of</strong> the<br />

environmental problem (or pressure) is broken. According to the OECD “relative<br />

decoupling” means that the economy grows faster than the environmental problem,<br />

29/09/09

ut both grow. “Absolute decoupling” means that the economy grows and the<br />

environmental problem declines. “Negative decoupling” implies that the<br />

environmental problem grows faster than the economy (in other words, there is no<br />

decoupling).<br />

The goal <strong>of</strong> prevention ought to be to achieve absolute decoupling, and to achieve a<br />

reduction in environmental pressure so as to ensure that future environmental quality<br />

is safeguarded, and environmental stocks are effectively managed for the long-term.<br />

The latter is not so easy to define. Hence, an important indicator will inevitably be the<br />

assessment <strong>of</strong> the degree <strong>of</strong> decoupling, because <strong>of</strong> the attention paid in Article 9,<br />

Article 29 (see above) and in the preamble (para 40) <strong>of</strong> the new WFD (see above).<br />

Point 3 <strong>of</strong> Annex IV refers to pressure related indicators (see Box 1).<br />

One formulation <strong>of</strong> a decoupling indicator r(t) for a given year t vis-à-vis a given<br />

reference year t0 is as follows: 9<br />

m(<br />

t)<br />

m(<br />

t0)<br />

r ( t)<br />

=<br />

a(<br />

t)<br />

a(<br />

t )<br />

9<br />

0<br />

where m(t) describes the environmental pressure in year t and a(t) describes the<br />

economic variable in year t (and similarly for time t= t0). In circumstances where the<br />

economic indicator is increasing, positive decoupling can be said to occur when the<br />

decoupling indicator is less than one. Absolute decoupling occurs when the<br />

numerator is less than one even where the economic indicator is greater than one.<br />

There is no decoupling when the indicator equals one. When the decoupling indicator<br />

is greater than one, then where the denominator is greater than one, there is negative<br />

decoupling. These rules have to be reconsidered in the context where the economy is<br />

in decline.<br />

In order to take into account the uncertainty factor in the estimations, a hypothesis<br />

test is needed when trying to determine whether or not there is decoupling. The<br />

uncertainty on the data for an individual production year can be relatively high, which<br />

complicates the estimate <strong>of</strong> decoupling. For that reason, the numerator and the<br />

denominator in the equation can be replaced by the inclination <strong>of</strong> a regression line,<br />

which <strong>of</strong>fers greater reliability and robustness than the estimate for a separate year. 10<br />

This methodology has been applied on Flemish data on waste production. Figure 1-1<br />

shows, as an example the decoupling indicator for the total production <strong>of</strong> industrial<br />

waste compared to the GDP for the periods: 1996-2000, 1997-2001, 1998-2002,<br />

1999-2003, 2000-2004, 2001-2005. 11<br />

9 Mike Van Acoleyen (2004) Indicators for <strong>Waste</strong> Prevention - Development <strong>of</strong> a Methodology for, and<br />

Testing <strong>of</strong> OECD Indicators, OVAM: Mechelen.<br />

10 J. Van Dijck (2004) Hypothese testen van indicatoren voor het afvalst<strong>of</strong>beleid, Probabilitas,<br />

Heverlee.<br />

11 OVAM (2008) Bedrijfsafvalst<strong>of</strong>fen: Cijfers en Trends voor Productie, Verwerking, Invoer en Uitvoer,.<br />

<strong>International</strong> <strong>Review</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Waste</strong> <strong>Policy</strong>: Annexes

For each indicator decoupling was calculated by comparing the regression <strong>of</strong> the<br />

pressure indicator (in this case waste production) with the economic indicator (in this<br />

case GDP) over the same period. Confidence intervals have been added to see if the<br />

indicator really is statistically sound above zero, which was the case until 2001. From<br />

2002 onwards, positive decoupling cannot with statistical certainty be proved for the<br />

Flemish region.<br />

Figure 1-1: Decoupling Indicator for Industrial <strong>Waste</strong> in Flanders<br />

In principle, the above formulation might be a little simplistic and a more general form<br />

might be:<br />

r =<br />

10<br />

( ∂m<br />

) ∂t<br />

( ∂a<br />

)<br />

29/09/09<br />

∂t<br />

This effectively compares the rate at which the pressure variable is changing over<br />

time relative to the rate <strong>of</strong> change in the economic variable.<br />

The somewhat hackneyed view that waste prevention ‘cannot be measured’ can be<br />

seen to be little more than an excuse not to act, or not to evaluate policies which,<br />

after all, are the ones which ought to be given the highest priority, both because <strong>of</strong><br />

their potential to reduce the waste <strong>of</strong> ‘other factors <strong>of</strong> production’ (solid wastes are<br />

<strong>of</strong>ten a symptom <strong>of</strong> other forms <strong>of</strong> waste), and because <strong>of</strong> their likely positive impact<br />

in terms <strong>of</strong> the environment and sustainable development. Finally, waste prevention<br />

measures frequently give rise to cost savings to businesses and consumers,<br />

suggesting that policy is failing to move these actors to a situation where waste is<br />

considered to be a variable cost in the production process.

1.4 <strong>Waste</strong> Recycling and Composting / Anaerobic Digestion<br />

The WFD defines ‘recycling’ as follows: 12<br />

11<br />

"recycling" means any recovery operation by which waste materials are<br />

reprocessed into products, materials or substances whether for the original or<br />

other purposes. It includes the reprocessing <strong>of</strong> organic material but does not<br />

include energy recovery and the reprocessing into materials that are to be<br />

used as fuels or for backfilling operations.<br />

As such, for the purposes <strong>of</strong> this report, we consider recycling to include the<br />

composting and anaerobic digestion <strong>of</strong> waste where this leads to the production <strong>of</strong> a<br />

useful output.<br />

Article 4(1), which sets out the waste hierarchy, places recycling below ‘prevention’<br />

and ‘preparing for re-use’, but above ‘other recovery’. Article 4(2) suggests that other<br />

than where life-cycle thinking suggests otherwise, recycling should be encouraged<br />

more strongly than either ‘other recovery’ or ‘disposal’, but not at the expense <strong>of</strong><br />

‘prevention’ and ‘preparing for re-use’.<br />

Article 10 states that:<br />

1. Member States shall take the necessary measures to ensure that waste<br />

undergoes recovery operations, in accordance with Articles 4 and 13.<br />

2. Where necessary to comply with paragraph 1 and to facilitate or improve<br />

recovery, waste shall be collected separately if technically, environmentally<br />

and economically practicable and shall not be mixed with other waste or other<br />

material with different properties.<br />

Whereas this does not establish any specific targets, Article 11, on Re-use and<br />

Recycling, states that:<br />

1. Member States shall take measures as appropriate to promote the re-use<br />

<strong>of</strong> products and preparing for re-use activities, notably through encouraging<br />

the establishment and support <strong>of</strong> re-use and repair networks, the use <strong>of</strong><br />

economic instruments, procurement criteria, quantitative objectives or other<br />

measures.<br />

Member States shall take measures to promote high quality recycling and to<br />

this end they shall set up separate collection <strong>of</strong> waste where technically,<br />

environmentally and economically practicable and appropriate to meet the<br />

necessary quality standards for the relevant recycling sectors.<br />

Subject to Article 10(2), by 2015 separate collection shall be set up for at<br />

least the following: paper, metal, plastic and glass.<br />

2. In order to comply with the objectives <strong>of</strong> this Directive, and to move towards<br />

a European recycling society with a high level <strong>of</strong> resource efficiency, Member<br />

12 Directive 2008/98/EC <strong>of</strong> the European Parliament and the Council <strong>of</strong> 19 November 2008 on <strong>Waste</strong><br />

and Repealing Certain Directives.<br />

<strong>International</strong> <strong>Review</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Waste</strong> <strong>Policy</strong>: Annexes

12<br />

29/09/09<br />

States shall take the necessary measures designed to achieve the following<br />

targets:<br />

a) by 2020 the preparing for re-use and the recycling <strong>of</strong> waste materials such as at<br />

least paper, metal, plastic and glass from households and possibly from other<br />

origins as far as these waste streams are similar to waste from households,<br />

shall be increased to a minimum <strong>of</strong> overall 50% by weight;<br />

b) by 2020 the preparing for re-use, recycling and other material recovery,<br />

including backfilling operations using waste to substitute other materials, <strong>of</strong><br />

non-hazardous construction and demolition waste excluding naturally occurring<br />

material defined in category 17 05 04 in the European <strong>Waste</strong> Catalogue (EWC)<br />

shall be increased to a minimum <strong>of</strong> 70% by weight.<br />

3. The Commission shall, in accordance with the regulatory procedure with<br />

scrutiny referred to in Article 39(2) <strong>of</strong> this Directive, establish detailed rules on<br />

the application and calculation methods for verifying compliance with the<br />

targets set out in paragraph 2 <strong>of</strong> this Article, considering Regulation (EC) No<br />

2150/2002 <strong>of</strong> the European Parliament and <strong>of</strong> the Council <strong>of</strong> 25 November<br />

2002 on waste statistics. These can include transition periods for Member<br />

States with less than 5% recycling in either category in 2008.<br />

4. By 31 December 2014 at the latest, the Commission shall examine the<br />

measures and the targets referred to in paragraph 2 with a view to, if<br />

necessary, reinforcing the targets and consider setting targets for other waste<br />

streams. The report <strong>of</strong> the Commission, accompanied by a proposal if<br />

appropriate, shall be sent to the European Parliament and the Council. In its<br />

report the Commission shall take into account the relevant environmental,<br />

economic and social impacts <strong>of</strong> setting the targets.<br />

5. Every three years, in accordance with Article 37, Member States shall<br />

report to the Commission on their record with regard to meeting the targets. If<br />

targets are not met, this report shall include the reasons for failure and the<br />

actions the Member State intends to take to meet the targets.<br />

Eunomia, as leaders in this study, is involved in work referred to under paragraph 3<br />

above. This is being led by the Oko Institut. For the time being, the Commission has<br />

issued, in response to a request to the United Kingdom, clarification <strong>of</strong> paragraph 2<br />

above (which is far from being unambiguous). The Commission stated: 13<br />

It is also the Commission services' understanding that the 50% target applies<br />

to the totality <strong>of</strong> at least four material waste streams including paper, plastics,<br />

glass and metals originating from households and possibly other sources, and<br />

does not apply individually to each <strong>of</strong> these waste streams. By "the totality" <strong>of</strong><br />

wastes we understand the amount <strong>of</strong> both separately collected and mixed<br />

13 Response from Commisioner, DG Environment, to letter from Roy Hathaway, Defra, dated 31 July<br />

2008.

13<br />

waste from these sources. Member States can add more material waste<br />

streams from household or similar wastes to this target (e.g. biowaste) in<br />

which case the 50% target would apply to the totality <strong>of</strong> all waste streams<br />

included. I would also like to draw your attention to Article 11(3) <strong>of</strong> the draft<br />

revised <strong>Waste</strong> Framework Directive which specifies that any eventual<br />

modalities related to the application and calculation methods for verifying<br />

compliance with the targets need to be elaborated by the Commission and the<br />

Member States in comitology.<br />

The most recent EPA report suggests that recycling rates for the four materials under<br />

consideration paper, metal, plastic, glass, was such that the target would be met for<br />

each <strong>of</strong> metals, paper and glass, but not plastic (see Table 1-1). The target would be<br />

met if one aggregated the figures for all 4 materials.<br />

The picture is quite different if one looks only at household waste (see Table 1-2).<br />

Here, the 50% target is not met for the materials in combination. The target is just<br />

exceeded for paper, it is easily exceeded for glass, but in respect <strong>of</strong> plastics and<br />

metals, the performance is below what is suggested.<br />

Pending the agreement <strong>of</strong> rules described in para 3 above, Ireland would appear to<br />

be already meeting targets for municipal waste, though the hierarchy and Article 10<br />

should still be followed, subject to life-cycle thinking suggesting otherwise. Hence, the<br />

target under the <strong>Waste</strong> Framework Directive should be considered a bare minimum,<br />

and in any case, it may yet be supplemented by a requirement to separate biowaste<br />

at source.<br />

Table 1-1: Recycling Performance for 4 Key WFD Materials, Municipal <strong>Waste</strong><br />

Managed Managed<br />

Managed Landfilled Landfilled<br />

Landfilled Recycled<br />

Recycled Recycled<br />

Recycled<br />

(tonnes)<br />

(tonnes) (tonnes)<br />

(tonnes) (tonnes)<br />

(tonnes) (%)<br />

(%)<br />

Metals 133,500 50,000 83,499 62.5%<br />

Paper 914,069 384,245 529,824 58.0%<br />

Plastic 288,760 223,755 65,005 22.5%<br />

Glass 182,554 48,075 134,479 73.7%<br />

Total 1,518,883 706,075 812,807 53.5%<br />

Source: EPA (2009) National <strong>Waste</strong> Report 2007, Wexford: EPA.<br />

Table 1-2: Recycling Performance for 4 Key WFD Materials, Household <strong>Waste</strong><br />

Managed Managed<br />

Managed Landfilled<br />

Landfilled Recycled<br />

Recycled Recycled<br />

Recycled<br />

(tonnes)<br />

(tonnes) (tonnes) (tonnes)<br />

(tonnes) (tonnes) (tonnes)<br />

(tonnes) (%)<br />

(%)<br />

Metals 48,021 35,577 12,444 25.9%<br />

Paper 385,074 187,350 197,724 51.3%<br />

Plastic 195,881 153,662 42,219 21.6%<br />

Glass 131,300 38,759 92,540 70.5%<br />

Total 760,276 415,348 344,927 45.4%<br />

Source: EPA (2009) National <strong>Waste</strong> Report 2007, Wexford: EPA.<br />

<strong>International</strong> <strong>Review</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Waste</strong> <strong>Policy</strong>: Annexes

As regards the WFD 70% target for re-use, recycling and recovery for construction and<br />

demolition waste, the latest EPA report indicates that Ireland is already achieving this<br />

target. Some caveats are necessary here, however, not least since the EPA Report<br />

highlights problems with the data. This is likely to be true in cases other than Ireland,<br />

and the challenge for many Member States will be to obtain quality data as to their<br />

current performance, not to mention that in the future.<br />

It will be clear that the above targets relate in the main to dry materials. The WFD also<br />

highlights the significance <strong>of</strong> the biowaste stream in Article 22, which states:<br />

14<br />

29/09/09<br />

Member States shall take measures, as appropriate, and in accordance with<br />

Articles 4 and 13, to encourage:<br />

a) the separate collection <strong>of</strong> bio-waste with a view to the composting<br />

and digestion <strong>of</strong> bio-waste;<br />

b) the treatment <strong>of</strong> bio-waste in a way that fulfils a high level <strong>of</strong><br />

environmental protection;<br />

c) the use <strong>of</strong> environmentally safe materials produced from bio-waste.<br />

The Commission shall carry out an assessment on the management <strong>of</strong> biowaste<br />

with a view to submitting a proposal if appropriate.<br />

The assessment shall examine the opportunity <strong>of</strong> setting minimum<br />

requirements for bio-waste management and quality criteria for compost and<br />

digestate from bio-waste, in order to guarantee a high level <strong>of</strong> protection for<br />

human health and the environment.<br />

In respect <strong>of</strong> the Commission’s above commitment, the Commission has already<br />

issued a Green Paper on the <strong>Management</strong> <strong>of</strong> Biowaste in the European Union. This<br />

asks a number <strong>of</strong> questions pertinent to the management <strong>of</strong> biowaste, and ends with<br />

the statement that: 14<br />

In late 2009, the Commission intends to present its analysis <strong>of</strong> the responses<br />

received together with, if appropriate, its proposals and/or initiatives for an EU<br />

strategy on the management <strong>of</strong> bio-waste.<br />

Ireland’s performance in respect <strong>of</strong> biowaste is far worse than on many <strong>of</strong> the dry<br />

recyclables. The latest EPA Report suggests that less than one tenth <strong>of</strong> the estimated<br />

918 thousand tonnes <strong>of</strong> organic waste was recovered. This stream has been the<br />

focus <strong>of</strong> much recent activity in the policy area. Circular WPPR 17/08 on the<br />

Implementation <strong>of</strong> Segregated ‘Brown Bin’ Collection for Biowaste and Home<br />

Composting was issued on 31 July 2008 to all City and County Managers. This affects<br />

the provision <strong>of</strong> separate collection services to households. More recently,<br />

consultation has been launched on a new Statutory Instrument, the <strong>Waste</strong><br />

14 Commission <strong>of</strong> the European Communities (2008) Green Paper on the <strong>Management</strong> <strong>of</strong> Biowaste in<br />

the European Union, COM(2008) 811 Final, Brussels, 3.12.08 (available at http://eurlex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=COM:2008:0811:FIN:EN:PDF).

<strong>Management</strong> (Food <strong>Waste</strong>) Regulations. This would effectively mandate the separate<br />

collection <strong>of</strong> food waste from waste producers, as defined under the instrument.<br />

Another important feature <strong>of</strong> the WFD, which is pertinent to the recycling <strong>of</strong> biowaste,<br />

is Article 6, which concerns the matter <strong>of</strong> whether, and if so, when, waste might cease<br />

to be treated as such (the ‘end <strong>of</strong> waste’ issues). The Article states: 15<br />

15<br />

1. Certain specified waste shall cease to be waste within the meaning <strong>of</strong> point<br />

(1) <strong>of</strong> Article 3 when it has undergone a recovery, , , including including recycling, recycling,<br />

operation and complies with specific criteria to be developed in accordance<br />

with the following conditions:<br />

a) the substance or object is commonly used for specific purposes purposes purposes ;<br />

b) a market or demand exists for such a substance or object;<br />

c) the substance or object fulfils the technical requirements for the<br />

specific purposes purposes and meets the existing legislation and standards<br />

applicable to products; and<br />

d) the use <strong>of</strong> the substance or object will not lead to overall adverse<br />

environmental or human health impacts.<br />

The criteria shall include limit values for pollutants where necessary and and shall<br />

shall<br />

take take into into account account account any any any possible possible advers adverse advers e environmental environmental environmental effects effects effects <strong>of</strong> <strong>of</strong> the<br />

the<br />

substance substance substance or or object object. object<br />

2. The measures relating to the adoption <strong>of</strong> such criteria and specifying the<br />

waste, designed to amend non-essential elements <strong>of</strong> this Directive, by<br />

supplementing it, shall be adopted in accordance with the regulatory<br />

procedure with scrutiny referred to in Article 39 (2). End End-<strong>of</strong> End <strong>of</strong> <strong>of</strong>-waste <strong>of</strong> waste specific<br />

specific<br />

criteria criteria should should be be be considered, considered, among among others, others, at at least least for for aggregates, aggregates, paper,<br />

paper,<br />

glass, glass, glass, metal, metal, metal, tyres tyres and textiles.<br />

3. <strong>Waste</strong> which ceases to be waste in accordance with paragraphs 1 and 2,<br />

shall also cease to be waste for the purpose <strong>of</strong> the recovery and recycling<br />

targets set out in Directives 94/62/EC, 2000/53/EC, 2002/96/EC and<br />

2006/66/EC and other relevant Community legislation when the recycling or or<br />

recovery recovery requirements requirements o<strong>of</strong><br />

o f that legislation are are met met. met<br />

4. Where criteria have not been set at Community level under the procedure<br />

set out in paragraphs 1 and 2, Member States may decide case by case<br />

whether certain waste has ceased to be waste taking into account the<br />

applicable case law. They shall notify the Commission <strong>of</strong> such decisions in<br />

accordance with Directive 98/34/EC <strong>of</strong> the European Parliament and <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Council <strong>of</strong> 22 June 1998 laying down a procedure for the provision <strong>of</strong><br />

information in the field <strong>of</strong> technical standards and regulations and <strong>of</strong> rules on<br />

Information Society services where so required by that Directive.<br />

15 Directive 2008/98/EC <strong>of</strong> the European Parliament and the Council <strong>of</strong> 19 November 2008 on <strong>Waste</strong><br />

and Repealing Certain Directives.<br />

<strong>International</strong> <strong>Review</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Waste</strong> <strong>Policy</strong>: Annexes

The Joint Research Centre (JRC) <strong>of</strong> the European Commission has been leading pilot<br />

studies on end-<strong>of</strong>-waste criteria for aggregates and for biowaste. A report has been<br />

published on the JRC website concerning the study. 16<br />

As far as recycling is concerned, the WFD effectively underpins the Producer<br />

Responsibility Directives already in place. These are:<br />

16<br />

� European Parliament and Council Directive 94/62/EC <strong>of</strong> 20 December 1994<br />

on packaging and packaging waste 17;<br />

� Directive 2000/53/EC <strong>of</strong> the European Parliament and <strong>of</strong> the Council <strong>of</strong><br />

18 September 2000 on end-<strong>of</strong> life vehicles; 18<br />

� Directive 2002/96/EC <strong>of</strong> the European Parliament and <strong>of</strong> the Council <strong>of</strong> 27<br />

January 2003 on waste electrical and electronic equipment<br />

(WEEE); 19http://www.europarl.europa.eu/sides/getDoc.do?pubRef=-<br />

//EP//TEXT+TA+P6-TA-2008-0282+0+DOC+XML+V0//EN&language=EN -<br />

def_2_14#def_2_14 and<br />

� Directive 2006/66/EC <strong>of</strong> the European Parliament and <strong>of</strong> the Council <strong>of</strong><br />

6 September 2006 on batteries and accumulators and waste batteries and<br />

accumulators. 20<br />

Article 8 <strong>of</strong> the WFD, on Extended Producer Responsibility, allows Member States<br />

considerable freedom to develop measures to encourage producers to take<br />

responsibility for their products. The ambition <strong>of</strong> Member State measures is certainly<br />

not restricted to those products already covered by EU Directives. The Article seems<br />

designed to allow Member States to develop their own initiatives in this regard (as<br />

some have done already – see Annex 15.0): 21<br />

29/09/09<br />

1. In order to strengthen the prevention, re-use, recycling and recovery <strong>of</strong><br />

waste, Member States may take legislative or non-legislative measures to<br />

ensure that any natural or legal person who pr<strong>of</strong>essionally develops,<br />

manufactures, processes, treats, sells or imports products (producer <strong>of</strong> the<br />

product) has extended producer responsibility.<br />

16 JRC (2009) End <strong>of</strong> <strong>Waste</strong> Criteria, JRC Scientific and Technical Reports,<br />

http://susproc.jrc.ec.europa.eu/activities/waste/documents/End<strong>of</strong>wastecriteriafinal.pdf<br />

17 OJ L 365, 31.12.1994, p. 10. Directive as last amended by Directive 2005/20/EC (OJ L 70,<br />

16.3.2005, p. 17).<br />

18 OJ L 269, 21.10.2000, p. 34. Directive as last amended by Directive 2008/33/EC <strong>of</strong> the European<br />

Parliament and <strong>of</strong> the Council (OJ L 81, 20.3.2008, p. 62 ).<br />

19 OJ L 37, 13.2.2003, p. 24. Directive as last amended by Directive 2008/34/EC (OJ L 81,<br />

20.3.2008, p. 65).<br />

20 OJ L 266, 26.9.2006, p. 1. Directive as last amended by Directive 2008/12/EC (OJ L 76,<br />

19.3.2008, p. 39).<br />

21 Directive 2008/98/EC <strong>of</strong> the European Parliament and the Council <strong>of</strong> 19 November 2008 on <strong>Waste</strong><br />

and Repealing Certain Directives.

17<br />

Such measures may include an acceptance <strong>of</strong> returned products and <strong>of</strong> the<br />

waste that remains after those products have been used, as well as the<br />

subsequent management <strong>of</strong> the waste and financial responsibility for such<br />