CROW

CROW

CROW

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Two canvas pieces—one white, one burgundy—meet<br />

at the corner of the living room<br />

walls. Across them are sprawled the words<br />

‘Split Decision—no one can do it for you.’<br />

Shae Therrien’s artwork echoes his state of<br />

mind, pulling in two directions, one dark,<br />

one light. An artist, boxer and writer, Therrien struggles<br />

with bipolar depression, characterized by extreme shifts<br />

in mood, behaviour and energy. Over the years he’s<br />

sought relief in everything from alcohol to electroshock<br />

on a journey that has brought both pain and inspiration.<br />

The journey began in 1998 in Armstrong, British<br />

Columbia, where Therrien worked at a fiberglass<br />

plant. He had been awake for three days straight. No<br />

matter how hard he worked out, or how exhausted his<br />

body was, his mind wouldn’t rest. It wouldn’t shut off.<br />

He stopped going to work and avoided his friends. Finally,<br />

after three weeks, he dialed his sister for help.<br />

“He said he had a knife and he was going to<br />

hurt himself,” Corrie Atkinson McLeod recalls.<br />

She acted fast, calling on a girlfriend who lived in<br />

Armstrong to stay with Therrien until she got there.<br />

She was on the next flight out to British Columbia from<br />

Saskatchewan. When she got there Therrien was clearly<br />

not himself. He seemed “flat,” speaking little. Tears ran<br />

down his cheeks. She drove him back to Saskatchewan<br />

and brought him to the Souris Valley Hospital in Weyburn,<br />

formerly known as the Weyburn Mental Hospital.<br />

For the next six months, Therrien called the hospital<br />

home. He was put on anti-depressants and sleep<br />

aid pills to help him stabilize. The medical staff also<br />

tried electro-convulsive therapy—electroshock—and it<br />

seemed to help. Slowly he climbed out of the depression.<br />

But Therrien wasn’t ready to accept his illness.<br />

“My sister told me that after I left (the hospital),<br />

‘You have to take these pills, this could happen<br />

again.’ And I just had no interest in that,” Therrien<br />

recalls. “As soon as I left Saskatchewan, I<br />

chucked my pills out the car window and drove.”<br />

He headed west, finding work on Alberta’s<br />

oil rigs. But his illness wasn’t so easily<br />

cast aside. He tried to ignore it by partying.<br />

“I found a lot of purpose in booze and drugs…<br />

Sometimes I would stay up for three or four<br />

days drinking and doing drugs, simply because<br />

I couldn’t sleep,” Therrien remembers.<br />

In 2003 Therrien had an accident on the rigs. In retrospect,<br />

he says it was the best thing that ever happened to<br />

him. He quit his job and headed back to Saskatchewan,<br />

mentally and physically battered. There he cleaned up,<br />

got off drugs and reunited with his family. He was taking<br />

his medicine again, and things seemed to improve.<br />

Then the manic side of bipolar hit. Years later,<br />

he wrote it was like being in rush hour traffic in<br />

New York but without streetlights and traffic signs:<br />

“Imagine complete chaos but everyone is happy.”<br />

He decided to become a healer, and that all he<br />

would have to do was touch people to heal them.<br />

Then he thought he would become God. Then he<br />

thought he was God. He ended up in a psych ward<br />

again, mind racing, thoughts snowballing out<br />

of control. Suddenly bliss turned into darkness.<br />

Although Therrien had resumed taking his anti-depressants,<br />

medicine alone wasn’t enough to<br />

keep depression at bay. Therrien’s doctor suggested<br />

he try electro-convulsive therapy again.<br />

ECT is a therapy cloaked in stigma, according to Rob<br />

Wekerle, program nurse at the Regina Qu’Appelle<br />

Health Region’s ECT clinic. Most people imagine<br />

scenes from Ken Kesey’s novel One Flew Over the<br />

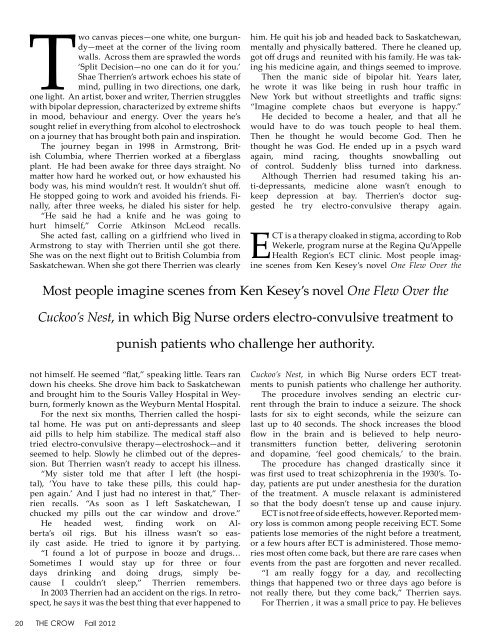

Most people imagine scenes from Ken Kesey’s novel One Flew Over the<br />

Cuckoo’s Nest, in which Big Nurse orders electro-convulsive treatment to<br />

punish patients who challenge her authority.<br />

Cuckoo’s Nest, in which Big Nurse orders ECT treatments<br />

to punish patients who challenge her authority.<br />

The procedure involves sending an electric current<br />

through the brain to induce a seizure. The shock<br />

lasts for six to eight seconds, while the seizure can<br />

last up to 40 seconds. The shock increases the blood<br />

flow in the brain and is believed to help neurotransmitters<br />

function better, delivering serotonin<br />

and dopamine, ‘feel good chemicals,’ to the brain.<br />

The procedure has changed drastically since it<br />

was first used to treat schizophrenia in the 1930’s. Today,<br />

patients are put under anesthesia for the duration<br />

of the treatment. A muscle relaxant is administered<br />

so that the body doesn’t tense up and cause injury.<br />

ECT is not free of side effects, however. Reported memory<br />

loss is common among people receiving ECT. Some<br />

patients lose memories of the night before a treatment,<br />

or a few hours after ECT is administered. Those memories<br />

most often come back, but there are rare cases when<br />

events from the past are forgotten and never recalled.<br />

“I am really foggy for a day, and recollecting<br />

things that happened two or three days ago before is<br />

not really there, but they come back,” Therrien says.<br />

For Therrien , it was a small price to pay. He believes<br />

the therapy gave him a second chance in life. “It’s like a<br />

reset button for my brain,” he says. He continues the treatments<br />

to this day. But ECT is not his only line of defense.<br />

Therrien hit the gym, joining the Regina Boxing<br />

Club in 2003. Boxing offered routine in the form<br />

of group calisthenics<br />

and timed workouts on a<br />

punching bag. It demanded<br />

focus, settling racing thoughts.<br />

Nowadays he leads the workouts<br />

every Monday and Friday<br />

evening. He greets the<br />

club members with jokes and<br />

laughter—and then begins<br />

yelling at them like a drill sergeant,<br />

driving them through<br />

laps around the gym. Later,<br />

he wraps his hands in tape,<br />

pulls on some bag gloves and<br />

settles into his own routine. Sweat drips down his<br />

forehead and the smack of his gloves on the heavy<br />

bag falls faster and faster with each ring of the bell.<br />

He sees his illness as a tricky opponent: to win, you<br />

need to devise a plan and stick to it. His art is part of the<br />

battle, too. Paintings fill his apartment, colourful works<br />

of eyes, pyramids and geometric shapes. Even his kitch-<br />

Therrien leads a workout at the boxing<br />

club. Below: The ECT treatment room<br />

at Regina’s General Hospital.<br />

en cabinets are an art project, sanded down and torched<br />

for a rustic look. His latest piece lies half assembled on<br />

the living room floor. Using small pieces of bamboo, he<br />

is tying together sticks to spell a quote from William<br />

Lyon Phelps: “This is the final test of a gentleman, his respect<br />

for those who can be of no possible service to him.”<br />

“This one is going to take a while,” he laughs and<br />

lights the second half of his<br />

Blackstone Cherry cigar.<br />

“The moment is all we have,”<br />

he says as he takes a drag<br />

and examines the letters.<br />

Bi-polar has taught him not<br />

to take anything for granted.<br />

For the last year Therrien has<br />

journaled daily. It has helped<br />

him come to terms with what<br />

it means to live a fulfilling life,<br />

and what that life looks like for<br />

him. Now Therrien is looking<br />

for a publisher so that his experiences<br />

and words can help someone else struggling<br />

with bi-polar. His manuscript, titled Interrupted with Bipolar,<br />

offers this signpost of hope for others on the road:<br />

My recovery, that I am continuing to believe I am never<br />

out of, shows me that those little setbacks can put me down for<br />

the depression 10-count, but I know I am never out of the<br />

fight. Never.<br />

20 THE <strong>CROW</strong> Fall 2012 Fall 2012 THE <strong>CROW</strong> 21