The Rapture of the Deep - Bronwen Dickey

The Rapture of the Deep - Bronwen Dickey

The Rapture of the Deep - Bronwen Dickey

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

TRAVEL<br />

by <strong>Bronwen</strong> <strong>Dickey</strong><br />

44 THE OXFORD AMERICAN } <strong>The</strong> Best <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> South 2011<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Rapture</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Deep</strong><br />

diving <strong>the</strong> sunken south.<br />

NOTICE IS HEREBY GIVEN BY DUKE POWER COMPANY…THAT THE PROPOSED KEOWEE-TOXAWAY PROJECT WILL<br />

FLOOD CERTAIN BURIAL GROUNDS AND GRAVES WITHIN THE AREA.<br />

—<strong>The</strong> Keowee Courier, South Carolina, June 8, 1967<br />

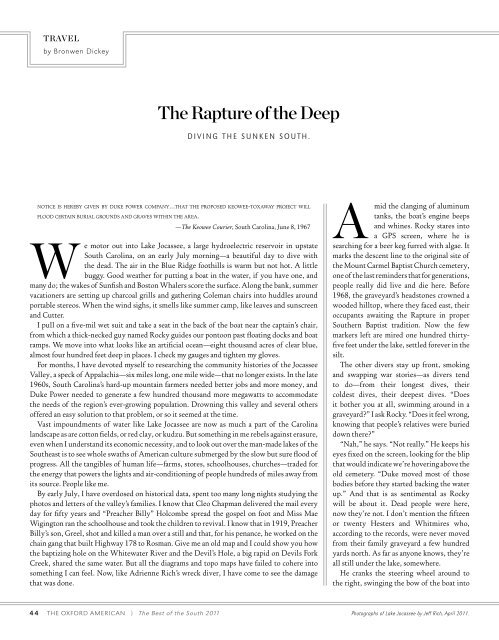

We motor out into Lake Jocassee, a large hydroelectric reservoir in upstate<br />

South Carolina, on an early July morning—a beautiful day to dive with<br />

<strong>the</strong> dead. <strong>The</strong> air in <strong>the</strong> Blue Ridge foothills is warm but not hot. A little<br />

buggy. Good wea<strong>the</strong>r for putting a boat in <strong>the</strong> water, if you have one, and<br />

many do; <strong>the</strong> wakes <strong>of</strong> Sunfish and Boston Whalers score <strong>the</strong> surface. Along <strong>the</strong> bank, summer<br />

vacationers are setting up charcoal grills and ga<strong>the</strong>ring Coleman chairs into huddles around<br />

portable stereos. When <strong>the</strong> wind sighs, it smells like summer camp, like leaves and sunscreen<br />

and Cutter.<br />

I pull on a five-mil wet suit and take a seat in <strong>the</strong> back <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> boat near <strong>the</strong> captain’s chair,<br />

from which a thick-necked guy named Rocky guides our pontoon past floating docks and boat<br />

ramps. We move into what looks like an artificial ocean—eight thousand acres <strong>of</strong> clear blue,<br />

almost four hundred feet deep in places. I check my gauges and tighten my gloves.<br />

For months, I have devoted myself to researching <strong>the</strong> community histories <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Jocassee<br />

Valley, a speck <strong>of</strong> Appalachia—six miles long, one mile wide—that no longer exists. In <strong>the</strong> late<br />

1960s, South Carolina’s hard-up mountain farmers needed better jobs and more money, and<br />

Duke Power needed to generate a few hundred thousand more megawatts to accommodate<br />

<strong>the</strong> needs <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> region’s ever-growing population. Drowning this valley and several o<strong>the</strong>rs<br />

<strong>of</strong>fered an easy solution to that problem, or so it seemed at <strong>the</strong> time.<br />

Vast impoundments <strong>of</strong> water like Lake Jocassee are now as much a part <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Carolina<br />

landscape as are cotton fields, or red clay, or kudzu. But something in me rebels against erasure,<br />

even when I understand its economic necessity, and to look out over <strong>the</strong> man-made lakes <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

Sou<strong>the</strong>ast is to see whole swaths <strong>of</strong> American culture submerged by <strong>the</strong> slow but sure flood <strong>of</strong><br />

progress. All <strong>the</strong> tangibles <strong>of</strong> human life—farms, stores, schoolhouses, churches—traded for<br />

<strong>the</strong> energy that powers <strong>the</strong> lights and air-conditioning <strong>of</strong> people hundreds <strong>of</strong> miles away from<br />

its source. People like me.<br />

By early July, I have overdosed on historical data, spent too many long nights studying <strong>the</strong><br />

photos and letters <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> valley’s families. I know that Cleo Chapman delivered <strong>the</strong> mail every<br />

day for fifty years and “Preacher Billy” Holcombe spread <strong>the</strong> gospel on foot and Miss Mae<br />

Wigington ran <strong>the</strong> schoolhouse and took <strong>the</strong> children to revival. I know that in 1919, Preacher<br />

Billy’s son, Greel, shot and killed a man over a still and that, for his penance, he worked on <strong>the</strong><br />

chain gang that built Highway 178 to Rosman. Give me an old map and I could show you how<br />

<strong>the</strong> baptizing hole on <strong>the</strong> Whitewater River and <strong>the</strong> Devil’s Hole, a big rapid on Devils Fork<br />

Creek, shared <strong>the</strong> same water. But all <strong>the</strong> diagrams and topo maps have failed to cohere into<br />

something I can feel. Now, like Adrienne Rich’s wreck diver, I have come to see <strong>the</strong> damage<br />

that was done.<br />

A<br />

mid <strong>the</strong> clanging <strong>of</strong> aluminum<br />

tanks, <strong>the</strong> boat’s engine beeps<br />

and whines. Rocky stares into<br />

a GPS screen, where he is<br />

searching for a beer keg furred with algae. It<br />

marks <strong>the</strong> descent line to <strong>the</strong> original site <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> Mount Carmel Baptist Church cemetery,<br />

one <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> last reminders that for generations,<br />

people really did live and die here. Before<br />

1968, <strong>the</strong> graveyard’s headstones crowned a<br />

wooded hilltop, where <strong>the</strong>y faced east, <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

occupants awaiting <strong>the</strong> <strong>Rapture</strong> in proper<br />

Sou<strong>the</strong>rn Baptist tradition. Now <strong>the</strong> few<br />

markers left are mired one hundred thirtyfive<br />

feet under <strong>the</strong> lake, settled forever in <strong>the</strong><br />

silt.<br />

<strong>The</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r divers stay up front, smoking<br />

and swapping war stories—as divers tend<br />

to do—from <strong>the</strong>ir longest dives, <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

coldest dives, <strong>the</strong>ir deepest dives. “Does<br />

it bo<strong>the</strong>r you at all, swimming around in a<br />

graveyard?” I ask Rocky. “Does it feel wrong,<br />

knowing that people’s relatives were buried<br />

down <strong>the</strong>re?”<br />

“Nah,” he says. “Not really.” He keeps his<br />

eyes fixed on <strong>the</strong> screen, looking for <strong>the</strong> blip<br />

that would indicate we’re hovering above <strong>the</strong><br />

old cemetery. “Duke moved most <strong>of</strong> those<br />

bodies before <strong>the</strong>y started backing <strong>the</strong> water<br />

up.” And that is as sentimental as Rocky<br />

will be about it. Dead people were here,<br />

now <strong>the</strong>y’re not. I don’t mention <strong>the</strong> fifteen<br />

or twenty Hesters and Whitmires who,<br />

according to <strong>the</strong> records, were never moved<br />

from <strong>the</strong>ir family graveyard a few hundred<br />

yards north. As far as anyone knows, <strong>the</strong>y’re<br />

all still under <strong>the</strong> lake, somewhere.<br />

He cranks <strong>the</strong> steering wheel around to<br />

<strong>the</strong> right, swinging <strong>the</strong> bow <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> boat into<br />

Photographs <strong>of</strong> Lake Jocassee by Jeff Rich, April 2011.