Diet of chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes schweinfurthii) at Ngogo ...

Diet of chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes schweinfurthii) at Ngogo ...

Diet of chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes schweinfurthii) at Ngogo ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

8 / W<strong>at</strong>ts et al.<br />

fruit in most years, whereas masting events, during<br />

which virtually all trees produced large fruit crops<br />

and the fruit domin<strong>at</strong>ed the chimpanzee diet for<br />

several months, occurred in 2000, 2005, and 2010<br />

(and 2011; d<strong>at</strong>a not included here: D. W<strong>at</strong>ts, personal<br />

observ<strong>at</strong>ion); each event started in July or August<br />

and continued for several months.<br />

Temporal Vari<strong>at</strong>ion in <strong>Diet</strong><br />

Feeding time devoted to individual species<br />

The proportion <strong>of</strong> feeding time th<strong>at</strong> the <strong>Ngogo</strong><br />

<strong>chimpanzees</strong> devoted to all ripe nonfig fruit varied<br />

positively with the RFSnff [W<strong>at</strong>ts et al., 2011]. The<br />

same result held for the individual major nonfig fruit<br />

foods in the diet. The species-specific RFS significantly<br />

predicted monthly feeding time for all 13<br />

major nonfig fruit foods included in the phenology<br />

sample (Table II; we did not include Pterygota<br />

mildbraedii because the <strong>chimpanzees</strong> mostly e<strong>at</strong><br />

seeds from unripe fruit <strong>of</strong> this species and leaves<br />

from saplings [Potts et al., 2011; W<strong>at</strong>ts et al., 2011;<br />

below]. Species-specific RFSs also significantly predicted<br />

the proportion <strong>of</strong> feeding time devoted to the<br />

four major species <strong>of</strong> figs in the diet (Table II; we did<br />

not include F. cy<strong>at</strong>histipula or F. exasper<strong>at</strong>a).<br />

Rel<strong>at</strong>ive foraging effort, defined as the extent to<br />

which the <strong>chimpanzees</strong> concentr<strong>at</strong>ed on a particular<br />

kind <strong>of</strong> fruit in rel<strong>at</strong>ion to its abundance, depended<br />

partly on how long fruit were available, on the<br />

frequency <strong>of</strong> fruiting events, and on the extent <strong>of</strong><br />

within-species fruiting synchrony. Overall, it was<br />

high for species th<strong>at</strong> infrequently produced fruit<br />

crops available for short periods (e.g., A. altissima,<br />

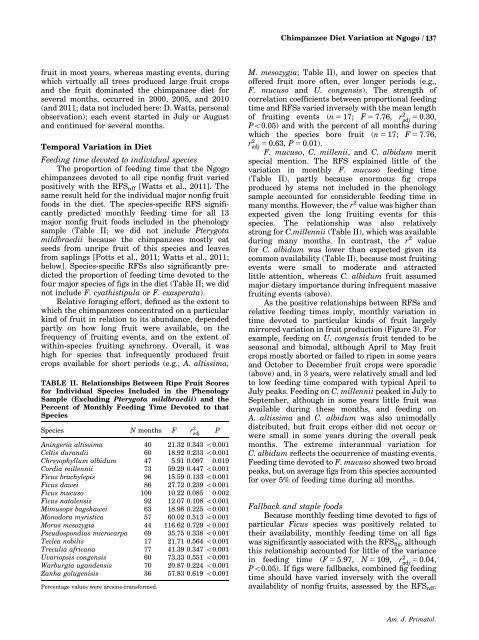

TABLE II. Rel<strong>at</strong>ionships Between Ripe Fruit Scores<br />

for Individual Species Included in the Phenology<br />

Sample (Excluding Pterygota mildbraedii) and the<br />

Percent <strong>of</strong> Monthly Feeding Time Devoted to th<strong>at</strong><br />

Species<br />

Species N months F r 2 adj P<br />

Aningeria altissima 40 21.32 0.343 o0.001<br />

Celtis durandii 60 18.92 0.233 o0.001<br />

Chrsyophyllum albidum 47 5.91 0.097 0.019<br />

Cordia millennii 73 59.29 0.447 o0.001<br />

Ficus brachylepis 96 15.59 0.133 o0.001<br />

Ficus dawei 86 27.72 0.239 o0.001<br />

Ficus mucuso 100 10.22 0.085 0.002<br />

Ficus n<strong>at</strong>alensis 92 12.07 0.108 o0.001<br />

Mimusops bagshawei 63 18.98 0.225 o0.001<br />

Monodora myristica 57 60.02 0.513 o0.001<br />

Morus mesozygia 44 116.62 0.729 o0.001<br />

Pseudospondias microcarpa 69 35.75 0.338 o0.001<br />

Teclea nobilis 17 21.71 0.564 o0.001<br />

Treculia africana 77 41.39 0.347 o0.001<br />

Uvariopsis congensis 60 73.33 0.551 o0.001<br />

Warburgia ugandensis 70 20.87 0.224 o0.001<br />

Zanha golugenisis 36 57.83 0.619 o0.001<br />

Percentage values were arcsine-transformed.<br />

Am. J. Prim<strong>at</strong>ol.<br />

Chimpanzee <strong>Diet</strong> Vari<strong>at</strong>ion <strong>at</strong> <strong>Ngogo</strong> /<br />

137<br />

M. mesozygia; Table II), and lower on species th<strong>at</strong><br />

<strong>of</strong>fered fruit more <strong>of</strong>ten, over longer periods (e.g.,<br />

F. mucuso and U. congensis). The strength <strong>of</strong><br />

correl<strong>at</strong>ion coefficients between proportional feeding<br />

time and RFSs varied inversely with the mean length<br />

<strong>of</strong> fruiting events (n 5 17; F 5 7.76, r2 adj 5 0.30,<br />

Po0.05) and with the percent <strong>of</strong> all months during<br />

which the species bore fruit (n 5 17; F 5 7.76,<br />

r2 adj 5 0.63, P 5 0.01).<br />

F. mucuso, C. millenii, and C. albidum merit<br />

special mention. The RFS explained little <strong>of</strong> the<br />

vari<strong>at</strong>ion in monthly F. mucuso feeding time<br />

(Table II), partly because enormous fig crops<br />

produced by stems not included in the phenology<br />

sample accounted for considerable feeding time in<br />

many months. However, the r 2 value was higher than<br />

expected given the long fruiting events for this<br />

species. The rel<strong>at</strong>ionship was also rel<strong>at</strong>ively<br />

strong for C.millennii (Table II), which was available<br />

during many months. In contrast, the r 2 value<br />

for C. albidum was lower than expected given its<br />

common availability (Table II), because most fruiting<br />

events were small to moder<strong>at</strong>e and <strong>at</strong>tracted<br />

little <strong>at</strong>tention, whereas C. albidum fruit assumed<br />

major dietary importance during infrequent massive<br />

fruiting events (above).<br />

As the positive rel<strong>at</strong>ionships between RFSs and<br />

rel<strong>at</strong>ive feeding times imply, monthly vari<strong>at</strong>ion in<br />

time devoted to particular kinds <strong>of</strong> fruit largely<br />

mirrored vari<strong>at</strong>ion in fruit production (Figure 3). For<br />

example, feeding on U. congensis fruit tended to be<br />

seasonal and bimodal, although April to May fruit<br />

crops mostly aborted or failed to ripen in some years<br />

and October to December fruit crops were sporadic<br />

(above) and, in 3 years, were rel<strong>at</strong>ively small and led<br />

to low feeding time compared with typical April to<br />

July peaks. Feeding on C. millennii peaked in July to<br />

September, although in some years little fruit was<br />

available during these months, and feeding on<br />

A. altissima and C. albidum was also unimodally<br />

distributed, but fruit crops either did not occur or<br />

were small in some years during the overall peak<br />

months. The extreme interannual vari<strong>at</strong>ion for<br />

C. albidum reflects the occurrence <strong>of</strong> masting events.<br />

Feeding time devoted to F. mucuso showed two broad<br />

peaks, but on average figs from this species accounted<br />

for over 5% <strong>of</strong> feeding time during all months.<br />

Fallback and staple foods<br />

Because monthly feeding time devoted to figs <strong>of</strong><br />

particular Ficus species was positively rel<strong>at</strong>ed to<br />

their availability, monthly feeding time on all figs<br />

was significantly associ<strong>at</strong>ed with the RFSfig, although<br />

this rel<strong>at</strong>ionship accounted for little <strong>of</strong> the variance<br />

in feeding time (F 5 5.97, N 5 109, r2 adj 5 0.04,<br />

Po0.05). If figs were fallbacks, combined fig feeding<br />

time should have varied inversely with the overall<br />

availability <strong>of</strong> nonfig fruits, assessed by the RFSnff. Am. J. Prim<strong>at</strong>ol.