The Scythians: nomad goldsmiths of the open steppes; The ...

The Scythians: nomad goldsmiths of the open steppes; The ...

The Scythians: nomad goldsmiths of the open steppes; The ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

L years, and it was Herodotus' ambi-'<br />

' tion to write <strong>the</strong> history <strong>of</strong> that war.<br />

Obviously, <strong>the</strong> <strong>Scythians</strong> must come<br />

into <strong>the</strong> story.<br />

<strong>The</strong>re were a great number <strong>of</strong><br />

people in Olbia who had spent <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

lives in <strong>the</strong> <strong>steppes</strong>, who had tra¬<br />

velled <strong>the</strong> length and breadth <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

lands north <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Black Sea, and<br />

who had many a tale to tell about<br />

<strong>the</strong> world <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Scythians</strong>, so dif¬<br />

ferent from that <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Greeks.<br />

Herodotus was an attentive listen¬<br />

er, and <strong>the</strong> contrasts with <strong>the</strong> way<br />

<strong>of</strong> life which he had known at home<br />

fascinated him. He wanted to<br />

write about all things unusual,<br />

leaving nothing out, and so he col¬<br />

lected all <strong>the</strong>se talesincluding <strong>the</strong><br />

unlikely onesfrom his Greek and<br />

Scythian informants, one <strong>of</strong> whom,<br />

a certain Tymnes, had actually been<br />

a man <strong>of</strong> confidence <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Scythian<br />

king Ariapei<strong>the</strong>s.<br />

What Herodotus saw for himself<br />

in Olbia, and what he heard, formed<br />

a colourful patchwork picture <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

Scythian world and Scythian ways,<br />

in which <strong>the</strong> past and <strong>the</strong> present,<br />

<strong>the</strong> important and <strong>the</strong> insignificant,<br />

<strong>the</strong> possible and <strong>the</strong> highly improb¬<br />

able jostled for space, and which<br />

he would incorporate in <strong>the</strong> pages<br />

<strong>of</strong> his History.<br />

Thus, <strong>the</strong> first record <strong>of</strong> its kind,<br />

by <strong>the</strong> man who has been called <strong>the</strong><br />

"Fa<strong>the</strong>r <strong>of</strong> History", would contain<br />

an account <strong>of</strong> one <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> first peoples<br />

identifiable by name to have inhabi¬<br />

ted what is now part <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Soviet<br />

Union.<br />

Herodotus was in Olbia in or<br />

about <strong>the</strong> year 450 B.C. Five years<br />

later, he was reading parts <strong>of</strong> his<br />

manuscript to <strong>the</strong> citizens <strong>of</strong> A<strong>the</strong>ns,<br />

who were so impressed that <strong>the</strong>y<br />

<strong>of</strong>fered him a grant <strong>of</strong> money to<br />

continue with his project.<br />

Let us listen with <strong>the</strong>m now to<br />

<strong>the</strong> words <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> narrator: "<strong>The</strong>ir land<br />

is level, well-watered, and abound¬<br />

ing in pasture"... "Having nei<strong>the</strong>r<br />

cities nor forts, and carrying <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

dwellings with <strong>the</strong>m wherever <strong>the</strong>y<br />

go; accustomed, moreover, one and<br />

all <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>m, to shoot from horse¬<br />

back; and living not by husbandry<br />

but <strong>the</strong>ir cattle, <strong>the</strong>ir waggons <strong>the</strong><br />

only homes that <strong>the</strong>y possess..."<br />

Thus Herodotus describes <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>nomad</strong>ic life <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Scythians</strong>,<br />

roaming in hordes over <strong>the</strong> "vastness<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> great plain" between <strong>the</strong><br />

Danube and <strong>the</strong> Don, women and<br />

children in <strong>the</strong> waggons and <strong>the</strong> men<br />

on horseback, ready at any moment<br />

to defend <strong>the</strong>ir families and <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

herds with <strong>the</strong>ir spears and with <strong>the</strong><br />

bows and arrows which <strong>the</strong>y handled<br />

with such skill.<br />

Being "entirely bare <strong>of</strong> trees", <strong>the</strong><br />

land <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Scythians</strong> was "utterly<br />

barren <strong>of</strong> firewood." <strong>The</strong>y stuffed<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir meat, haggis-wise, into <strong>the</strong><br />

stomach <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> animal, and cooked<br />

it in cauldrons over a fire made<br />

with <strong>the</strong> animal's own bones. In<br />

10<br />

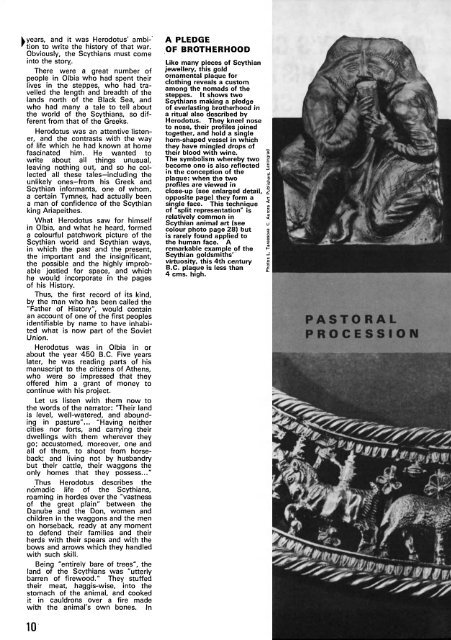

A PLEDGE<br />

OF BROTHERHOOD<br />

Like many pieces <strong>of</strong> Scythian<br />

jewellery, this gold<br />

ornamental plaque for<br />

clothing reveals a custom<br />

among <strong>the</strong> <strong>nomad</strong>s <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>steppes</strong>. It shows two<br />

<strong>Scythians</strong> making a pledge<br />

<strong>of</strong> everlasting bro<strong>the</strong>rhood in<br />

a ritual also described by<br />

Herodotus. <strong>The</strong>y kneel nose<br />

to nose, <strong>the</strong>ir pr<strong>of</strong>iles joined<br />

toge<strong>the</strong>r, and hold a single<br />

horn-shaped vessel in which<br />

<strong>the</strong>y have mingled drops <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong>ir blood with wine.<br />

<strong>The</strong> symbolism whereby two<br />

become one is also reflected<br />

in <strong>the</strong> conception <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

plaque: when <strong>the</strong> two<br />

pr<strong>of</strong>iles are viewed in<br />

close-up (see enlarged detail,<br />

opposite page) .<strong>the</strong>y form a<br />

single face. This technique<br />

<strong>of</strong> "split representation" is<br />

relatively common in<br />

Scythian animal art (see<br />

colour photo page 28) but<br />

is rarely found applied to<br />

<strong>the</strong> human face. A<br />

remarkable example <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

Scythian <strong>goldsmiths</strong>'<br />

virtuosity, this 4th century<br />

B.C. plaque is less than<br />

4 cms. high.