here - The Chartered Society of Physiotherapy

here - The Chartered Society of Physiotherapy

here - The Chartered Society of Physiotherapy

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

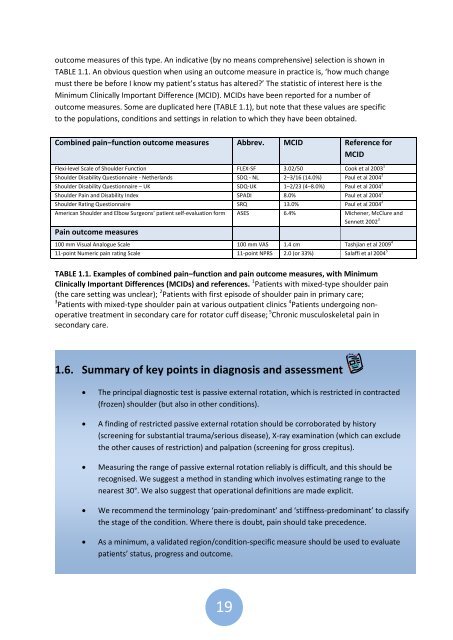

outcome measures <strong>of</strong> this type. An indicative (by no means comprehensive) selection is shown in<br />

TABLE 1.1. An obvious question when using an outcome measure in practice is, ‘how much change<br />

must t<strong>here</strong> be before I know my patient’s status has altered?’ <strong>The</strong> statistic <strong>of</strong> interest <strong>here</strong> is the<br />

Minimum Clinically Important Difference (MCID). MCIDs have been reported for a number <strong>of</strong><br />

outcome measures. Some are duplicated <strong>here</strong> (TABLE 1.1), but note that these values are specific<br />

to the populations, conditions and settings in relation to which they have been obtained.<br />

Combined pain‒function outcome measures Abbrev. MCID Reference for<br />

MCID<br />

Flexi-level Scale <strong>of</strong> Shoulder Function FLEX-SF 3.02/50 Cook et al 2003 1<br />

Shoulder Disability Questionnaire - Netherlands SDQ - NL 2‒3/16 (14.0%) Paul et al 2004 2<br />

Shoulder Disability Questionnaire – UK SDQ-UK 1‒2/23 (4‒8.0%) Paul et al 2004 2<br />

Shoulder Pain and Disability Index SPADI 8.0% Paul et al 2004 2<br />

Shoulder Rating Questionnaire SRQ 13.0% Paul et al 2004 2<br />

American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons’ patient self-evaluation form ASES 6.4% Michener, McClure and<br />

Sennett 2002 3<br />

Pain outcome measures<br />

100 mm Visual Analogue Scale 100 mm VAS 1.4 cm Tashjian et al 2009 4<br />

11-point Numeric pain rating Scale 11-point NPRS 2.0 (or 33%) Salaffi et al 2004 5<br />

TABLE 1.1. Examples <strong>of</strong> combined pain‒function and pain outcome measures, with Minimum<br />

Clinically Important Differences (MCIDs) and references. 1 Patients with mixed-type shoulder pain<br />

(the care setting was unclear); 2 Patients with first episode <strong>of</strong> shoulder pain in primary care;<br />

3 Patients with mixed-type shoulder pain at various outpatient clinics 4 Patients undergoing nonoperative<br />

treatment in secondary care for rotator cuff disease; 5 Chronic musculoskeletal pain in<br />

secondary care.<br />

1.6. Summary <strong>of</strong> key points in diagnosis and assessment<br />

<strong>The</strong> principal diagnostic test is passive external rotation, which is restricted in contracted<br />

(frozen) shoulder (but also in other conditions).<br />

A finding <strong>of</strong> restricted passive external rotation should be corroborated by history<br />

(screening for substantial trauma/serious disease), X-ray examination (which can exclude<br />

the other causes <strong>of</strong> restriction) and palpation (screening for gross crepitus).<br />

Measuring the range <strong>of</strong> passive external rotation reliably is difficult, and this should be<br />

recognised. We suggest a method in standing which involves estimating range to the<br />

nearest 30°. We also suggest that operational definitions are made explicit.<br />

We recommend the terminology ‘pain-predominant’ and ‘stiffness-predominant’ to classify<br />

the stage <strong>of</strong> the condition. W<strong>here</strong> t<strong>here</strong> is doubt, pain should take precedence.<br />

As a minimum, a validated region/condition-specific measure should be used to evaluate<br />

patients’ status, progress and outcome.<br />

19