Open - IHDP - United Nations University

Open - IHDP - United Nations University

Open - IHDP - United Nations University

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Indentifying the Poor in Cities<br />

There is an uncontrolled influx of people from rural<br />

regions to the megacity of Dhaka (BEguM 1999), yet this in-<br />

flux or city in-migration, is not accompanied by growth of<br />

urban infrastructure and supply. Thus, many migrants move<br />

into marginal areas already in critical situations, and result<br />

in the persistent and increasing resource pressure in these<br />

settlements. Insufficient water supply, waste disposal and<br />

waste water treatment as well as traumatic hygienic conditions<br />

and lack of access to basic services mark the living conditions<br />

in these slums. Slum dwellers, on average, have poorer<br />

health and are more vulnerable to disasters such as floods<br />

(uN MILLENNIuM ProjECt 2005). At present, about one third<br />

of Dhaka’s population lives in marginal settlements or slums<br />

(BurkArt Et AL. 2008).<br />

A further problem is that of environmental pollution<br />

as a result of poorly developed infrastructure. Soil, air and<br />

water pollution occurs through the burning of wastes such<br />

as plastics and through a lack of sanitation. A rudimentary<br />

suburban traffic system does not offer<br />

alternatives and people thus use small motorcycles<br />

and cars for mobility. The constantly growing<br />

traffic that results with its associated emissions<br />

adds to the contamination of urban air.<br />

The three large rivers systems, the Gangha,<br />

Brahmaputra and Meghna, flood each year, since<br />

the artificially installed drainage systems cannot<br />

handle the water masses sufficiently. The result<br />

is an amplified surface discharge during the<br />

monsoon season in particular, which lasts from<br />

March until October. The slums, with all their<br />

shanties, are thus seasonally threatened by such<br />

floods, exacerbating the already precarious situation<br />

faced by the inhabitants (CALdwELL 2004;<br />

khAN 2007).<br />

In the current investigation on the structure<br />

of slum settlements in Dhaka, Bangladesh,<br />

the goal is to prepare a vegetation-index (NDVI)<br />

based analysis exploiting Quickbird VHR satellite<br />

data in an object oriented classification scheme<br />

and further GIS analysis to investigate the living<br />

conditions and health endangerment for the inhabitants<br />

in the slums of Karail and Badda. The<br />

informal settlement of Karail has been choosen<br />

due to its prominent status as largest marginal<br />

quarter in Dhaka. (sEE FIg. 1). The vast majority<br />

of Karail was mapped as slum area, and on closer<br />

inspection of the original Quickbird data, an extremely<br />

high building density was uncovered. The<br />

land-use/land-cover classification and the NDVI<br />

mapping shown in Figure 2 highlight the tremendous differences<br />

in land-use patterns which can be found in Dhaka on<br />

a very large scale, showing an extreme lack of vegetation in<br />

poor areas and dispersed green spaces for middle and upper<br />

class areas. The slum area of Karail is located in the west of<br />

the map shown and identified as the one with the smallest<br />

NDVI-values. On the island in between the water bodies,<br />

there are upper middle to upper class residential neighbourhoods,<br />

including some residents with diplomatic status.<br />

These neighbourhoods show dispersed, multi-storey apartment<br />

buildings and a high proportion of green and open<br />

spaces. Again, this area contrasts with the urban area in the<br />

east of this study, where one can find a land-use mosaic of<br />

different building densities with a mix of rapidly changing<br />

apartment blocks and shanties.<br />

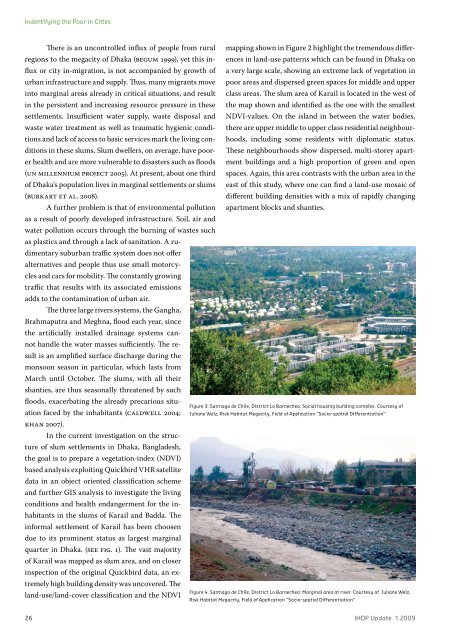

Figure 3: Santiago de Chile, District Lo Barnechea: Social housing building complex. Courtesy of<br />

Juliane Welz, Risk Habitat Megacity, Field of Application “Socio-spatial Differentiation”<br />

Figure 4: Santiago de Chile, District Lo Barnechea: Marginal area at river. Courtesy of Juliane Welz,<br />

Risk Habitat Megacity, Field of Application “Socio-spatial Differentiation”<br />

26 <strong>IHDP</strong> Update 1.2009