View - School of Geosciences

View - School of Geosciences

View - School of Geosciences

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Multiple deformation around Taemas Bridge 831<br />

appear to be restricted to the Currowong Syncline (Lyons<br />

et al. 2000; Glen et al. 2002; Packham) and Jesse Syncline<br />

(Glen & Watkins 1999) and grade into sub-concordance<br />

north and south, respectively, along strike. Consistent, very<br />

gentle to gentle, tilts over many kilometres (plus or minus<br />

some faulting: Glen & Watkins 1999) seem much more<br />

prevalent. The Warrumba Volcanics and Dulladerry<br />

Volcanics are clear examples representing the early Late<br />

Devonian phase <strong>of</strong> the unconformity movement in the<br />

Cowra Trough area. These upper Middle to lowermost<br />

Upper Devonian (Packham) volcanics thicken continuously<br />

from 0 m to up to ~2500 m over about 20 km northwards<br />

beneath the Hervey Group (after mapping by<br />

Conolly 1965; Raymond & Pogson 1998; Raymond et al.<br />

2001). The data indicate tilt components <strong>of</strong> ~6 and ~8 for<br />

the respective volcanics to the north. Significantly, the<br />

discordance components across strike <strong>of</strong> the dominant<br />

sub-meridional folds are similar or less and are likewise<br />

consistently orientated, implying no folding <strong>of</strong> the<br />

volcanics prior to deposition <strong>of</strong> the Upper Devonian.<br />

(5) Sub-upper Middle Devonian unconformity Nonconformable<br />

relationships <strong>of</strong> the Dulladerry Volcanics and<br />

coeval Comerong Volcanics/Boyd Volcanic Complex with<br />

underlying Emsian–Eifelian and Early Devonian granites<br />

(Packham) represent a further and older erosion phase,<br />

some time within the early Eifelian to early Givetian<br />

interval. Angularity cannot be assessed from these<br />

relations and so must be sought elsewhere. The sites<br />

involving Upper Silurian to lower Middle Devonian strata<br />

mentioned in point (1) would incorporate any movement <strong>of</strong><br />

this age. These, together with known conformable<br />

relations <strong>of</strong> lower Middle Devonian Hatchery Creek<br />

Conglomerate (discussed in Hood & Durney 2002) and<br />

Boogledie Formation (Packham) with underlying Lower<br />

Devonian limestones, suggest generally low to no angularity<br />

for this phase.<br />

(6) Moura Formation The single case <strong>of</strong> consistently<br />

higher discordance angle noted by Packham—the gentle to<br />

moderate 26 and 42 local-means <strong>of</strong> Powell et al. (1980)<br />

between the ?Siluro-Devonian Moura Formation and<br />

Upper Devonian in the Parkes Syncline—may not<br />

represent ca Middle Devonian movement as the tilting<br />

may have occurred prior to or during intrusion <strong>of</strong> the<br />

late Early Devonian Eugowra Granite.<br />

What are the relationships between folds in Upper<br />

Devonian and Lower to Middle Devonian strata?<br />

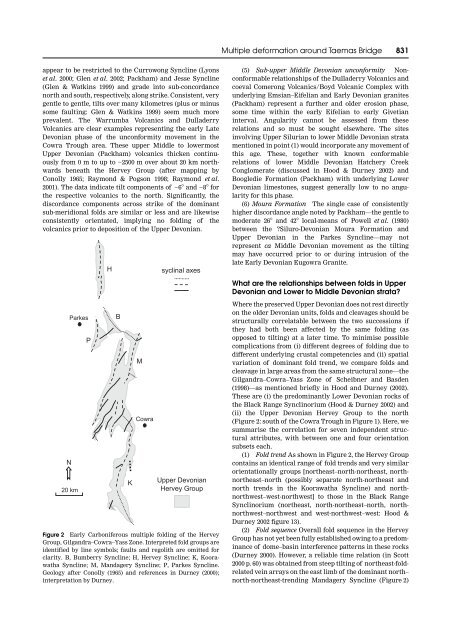

Figure 2 Early Carboniferous multiple folding <strong>of</strong> the Hervey<br />

Group, Gilgandra–Cowra–Yass Zone. Interpreted fold groups are<br />

identified by line symbols; faults and regolith are omitted for<br />

clarity. B, Bumberry Syncline; H, Hervey Syncline; K, Koorawatha<br />

Syncline; M, Mandagery Syncline; P, Parkes Syncline.<br />

Geology after Conolly (1965) and references in Durney (2000);<br />

interpretation by Durney.<br />

Where the preserved Upper Devonian does not rest directly<br />

on the older Devonian units, folds and cleavages should be<br />

structurally correlatable between the two successions if<br />

they had both been affected by the same folding (as<br />

opposed to tilting) at a later time. To minimise possible<br />

complications from (i) different degrees <strong>of</strong> folding due to<br />

different underlying crustal competencies and (ii) spatial<br />

variation <strong>of</strong> dominant fold trend, we compare folds and<br />

cleavage in large areas from the same structural zone—the<br />

Gilgandra–Cowra–Yass Zone <strong>of</strong> Scheibner and Basden<br />

(1998)—as mentioned briefly in Hood and Durney (2002).<br />

These are (i) the predominantly Lower Devonian rocks <strong>of</strong><br />

the Black Range Synclinorium (Hood & Durney 2002) and<br />

(ii) the Upper Devonian Hervey Group to the north<br />

(Figure 2: south <strong>of</strong> the Cowra Trough in Figure 1). Here, we<br />

summarise the correlation for seven independent structural<br />

attributes, with between one and four orientation<br />

subsets each.<br />

(1) Fold trend As shown in Figure 2, the Hervey Group<br />

contains an identical range <strong>of</strong> fold trends and very similar<br />

orientationally groups [northeast–north-northeast, northnortheast–north<br />

(possibly separate north-northeast and<br />

north trends in the Koorawatha Syncline) and northnorthwest–west-northwest]<br />

to those in the Black Range<br />

Synclinorium (northeast, north-northeast–north, northnorthwest–northwest<br />

and west-northwest–west: Hood &<br />

Durney 2002 figure 13).<br />

(2) Fold sequence Overall fold sequence in the Hervey<br />

Group has not yet been fully established owing to a predominance<br />

<strong>of</strong> dome–basin interference patterns in these rocks<br />

(Durney 2000). However, a reliable time relation (in Scott<br />

2000 p. 60) was obtained from steep tilting <strong>of</strong> northeast-foldrelated<br />

vein arrays on the east limb <strong>of</strong> the dominant north–<br />

north-northeast-trending Mandagery Syncline (Figure 2)