Download this document - Institute for Agriculture and Trade Policy

Download this document - Institute for Agriculture and Trade Policy

Download this document - Institute for Agriculture and Trade Policy

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

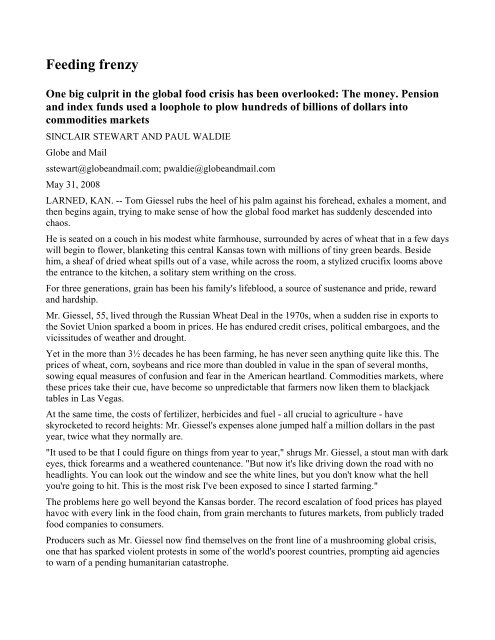

Feeding frenzy<br />

One big culprit in the global food crisis has been overlooked: The money. Pension<br />

<strong>and</strong> index funds used a loophole to plow hundreds of billions of dollars into<br />

commodities markets<br />

SINCLAIR STEWART AND PAUL WALDIE<br />

Globe <strong>and</strong> Mail<br />

sstewart@globe<strong>and</strong>mail.com; pwaldie@globe<strong>and</strong>mail.com<br />

May 31, 2008<br />

LARNED, KAN. -- Tom Giessel rubs the heel of his palm against his <strong>for</strong>ehead, exhales a moment, <strong>and</strong><br />

then begins again, trying to make sense of how the global food market has suddenly descended into<br />

chaos.<br />

He is seated on a couch in his modest white farmhouse, surrounded by acres of wheat that in a few days<br />

will begin to flower, blanketing <strong>this</strong> central Kansas town with millions of tiny green beards. Beside<br />

him, a sheaf of dried wheat spills out of a vase, while across the room, a stylized crucifix looms above<br />

the entrance to the kitchen, a solitary stem writhing on the cross.<br />

For three generations, grain has been his family's lifeblood, a source of sustenance <strong>and</strong> pride, reward<br />

<strong>and</strong> hardship.<br />

Mr. Giessel, 55, lived through the Russian Wheat Deal in the 1970s, when a sudden rise in exports to<br />

the Soviet Union sparked a boom in prices. He has endured credit crises, political embargoes, <strong>and</strong> the<br />

vicissitudes of weather <strong>and</strong> drought.<br />

Yet in the more than 3½ decades he has been farming, he has never seen anything quite like <strong>this</strong>. The<br />

prices of wheat, corn, soybeans <strong>and</strong> rice more than doubled in value in the span of several months,<br />

sowing equal measures of confusion <strong>and</strong> fear in the American heartl<strong>and</strong>. Commodities markets, where<br />

these prices take their cue, have become so unpredictable that farmers now liken them to blackjack<br />

tables in Las Vegas.<br />

At the same time, the costs of fertilizer, herbicides <strong>and</strong> fuel - all crucial to agriculture - have<br />

skyrocketed to record heights: Mr. Giessel's expenses alone jumped half a million dollars in the past<br />

year, twice what they normally are.<br />

"It used to be that I could figure on things from year to year," shrugs Mr. Giessel, a stout man with dark<br />

eyes, thick <strong>for</strong>earms <strong>and</strong> a weathered countenance. "But now it's like driving down the road with no<br />

headlights. You can look out the window <strong>and</strong> see the white lines, but you don't know what the hell<br />

you're going to hit. This is the most risk I've been exposed to since I started farming."<br />

The problems here go well beyond the Kansas border. The record escalation of food prices has played<br />

havoc with every link in the food chain, from grain merchants to futures markets, from publicly traded<br />

food companies to consumers.<br />

Producers such as Mr. Giessel now find themselves on the front line of a mushrooming global crisis,<br />

one that has sparked violent protests in some of the world's poorest countries, prompting aid agencies<br />

to warn of a pending humanitarian catastrophe.

In the search <strong>for</strong> answers, pundits have attempted to pin the blame on the usual suspects: rising dem<strong>and</strong><br />

from China <strong>and</strong> India, bad crop conditions <strong>and</strong> booming ethanol production.<br />

Yet one major culprit behind these gyrating markets <strong>and</strong> unprecedented price spikes has been largely<br />

overlooked: the deep-pocketed pension <strong>and</strong> index funds upon which most Canadians <strong>and</strong> Americans<br />

depend <strong>for</strong> their retirements.<br />

These funds have plowed tens of billions of dollars into agricultural commodities as a way to diversify<br />

their assets <strong>and</strong> improve returns <strong>for</strong> their investors.<br />

The amount of fund money invested in commodity indexes has climbed from just $13-billion (U.S.) in<br />

2003 to a staggering $260-billion in March, 2008, according to calculations based on regulatory filings.<br />

Michael Masters, a veteran U.S. hedge fund manager, warned a Senate hearing <strong>this</strong> month that <strong>this</strong><br />

number could easily quadruple to $1-trillion, if pension funds allocate a greater portion of their<br />

portfolio to commodities, as some consultants suggest they are poised to do. Because agricultural<br />

markets are small - relative to stock markets - the amount of cash pouring in gives these funds<br />

substantial clout. Mr. Masters estimated that that these big institutional investors control enough wheat<br />

futures to supply the needs of American consumers <strong>for</strong> the next two years, <strong>and</strong> blamed the "dem<strong>and</strong><br />

shock" from these recent entrants to the commodities markets as arguably the primary factor behind the<br />

sudden take-off in food prices.<br />

"If immediate action is not taken, food <strong>and</strong> energy prices will rise higher still," he told the hearing.<br />

"This could have catastrophic economic effects on millions of already stressed U.S. consumers. It<br />

literally could mean starvation <strong>for</strong> millions of the world's poor."<br />

The massive influx of cash has only occurred in the past few years. But its roots stretch back to the<br />

Reagan era, when a court battle over oil price manipulation set off a domino effect that would<br />

ultimately trans<strong>for</strong>m the arcane world of commodities trading.<br />

Beginning with the energy market, regulators made a series of far-reaching decisions that gradually<br />

loosened oversight of complex commodity derivatives <strong>and</strong> created loopholes <strong>for</strong> large speculators,<br />

allowing them to trade virtually unlimited amounts of corn, wheat <strong>and</strong> other food futures.<br />

Only now, nearly two decades later, are the full consequences of those decisions being felt.<br />

Any more<br />

For months, governments <strong>and</strong> international bodies have been struggling to avert catastrophe. The<br />

United Nations created a special task <strong>for</strong>ce on food security <strong>and</strong> called <strong>for</strong> emergency donations.<br />

Leaders of the world's wealthiest countries are expected to make the food crisis a priority when they<br />

gather <strong>for</strong> a G8 summit in July.<br />

And the U.S. Congress has convened hearings into the matter, as have various other governmental <strong>and</strong><br />

regulatory bodies around the world, all in an attempt to underst<strong>and</strong> how markets <strong>and</strong> prices careened<br />

out of control.<br />

They would do well to ask Fowler West. At a pivotal moment almost 20 years ago, Mr. West warned<br />

that a series of rapid-fire moves to deregulate commodities trading could wreak unintended - <strong>and</strong><br />

perhaps calamitous - effects on these markets.<br />

His alarms went unheeded.<br />

In the early 1990s, Mr. West held a seat as a commissioner on the Commodity Futures Trading<br />

Commission, the U.S. regulator charged with overseeing trading in hundreds of staple items, from corn<br />

<strong>and</strong> wheat to oil <strong>and</strong> cotton. Mr. West was a lifelong Democrat; his boss, CFTC chair Wendy Gramm,

was a devout Republican <strong>and</strong> a believer in the laissez-faire, free-market philosophy espoused by<br />

president Ronald Reagan, who once described her as his "favourite economist."<br />

In the fall of 1990, the two clashed over the CFTC's response to a New York court decision involving a<br />

little-known Bermuda energy company called Transnor Ltd.<br />

Long <strong>for</strong>gotten by most, Transnor paved the way <strong>for</strong> wide-ranging deregulation of commodities<br />

trading, an ef<strong>for</strong>t that helped to spur the rise of Enron Corp. <strong>and</strong> which has enabled the stampede of<br />

large fund speculators into food markets.<br />

In the winter of 1986, Transnor filed suit against some of the world's largest oil companies, alleging<br />

that they manipulated prices on the Brent market, an in<strong>for</strong>mal oil trading system that at the time<br />

determined the daily price of oil.<br />

At first, few paid attention to the lawsuit. That all changed on April 18, 1990, when Judge William<br />

Conner delivered a stunning ruling midway through the trial.<br />

The case hinged on drawing a key distinction: Were the 15-day oil contracts that traded on the Brent<br />

market "<strong>for</strong>ward contracts" or "futures contracts"?<br />

In a <strong>for</strong>ward contract, the buyer <strong>and</strong> seller agree to the price of a commodity <strong>and</strong> a fixed date <strong>for</strong><br />

delivery. A farmer enters into a <strong>for</strong>ward contract with a food company by promising to deliver a certain<br />

amount of grain on a certain date at a certain price. Lawmakers have shied away from regulating<br />

<strong>for</strong>ward contracts under commodity trading laws because they are a fundamental part of how farmers<br />

<strong>and</strong> food companies do business - <strong>and</strong> each agreement is unique.<br />

A futures contract is the same basic agreement, but it trades on an exchange, <strong>and</strong> the buyer rarely - if<br />

ever - takes delivery of the commodities. Instead, futures contracts are used mainly by farmers <strong>for</strong><br />

hedging <strong>and</strong> by investors <strong>for</strong> speculating. These contracts have historically been regulated.<br />

In the Brent case, the difference was crucial, since the Brent market contracts did not trade on any<br />

exchange <strong>and</strong>, in the U.S., were not regulated by the CFTC.<br />

The oil companies, hoping to protect their cozy market, <strong>and</strong> avoid the red tape <strong>and</strong> transparency<br />

requirements of regulation, argued they were <strong>for</strong>ward contracts.<br />

Judge Conner ruled against the companies, effectively rendering all Brent trading in the U.S. illegal.<br />

Within days, international oil companies stopped trading with U.S. companies <strong>and</strong> the entire Brent<br />

market was verging on collapse.<br />

In Washington, oil industry lobbyists descended on the CFTC, seeking to get the regulator to mitigate<br />

Judge Conner's ruling. They found a receptive ear in Ms. Gramm, the commission chair. Ms. Gramm<br />

served as a director at the Office of Management <strong>and</strong> Budget, spearheading a variety of industry<br />

deregulation ef<strong>for</strong>ts be<strong>for</strong>e President Reagan placed her in charge of the CFTC in 1988.<br />

She arrived with other political credentials: her husb<strong>and</strong>, Phil, who is now a senior economic adviser to<br />

presidential c<strong>and</strong>idate John McCain, was a Republican senator from Texas.<br />

Even be<strong>for</strong>e the Transnor case, Ms. Gramm had started pursuing a deregulation agenda at the CFTC. A<br />

year earlier, in 1989, the commission quietly issued a policy statement on swap transactions, deals in<br />

which a buyer of commodities such as a pension fund acts through a middleman or a swap dealer -<br />

usually a bank. The CFTC declared that it wouldn't regulate swap dealers.<br />

The Transnor case represented another crucial win <strong>for</strong> financial speculators such as swap dealers.<br />

When the court decision was h<strong>and</strong>ed down, Ms. Gramm moved quickly to soften the blow to the

energy sector, <strong>and</strong> turned the Transnor decision from an obscure footnote in the history of oil trading<br />

into a critical launching pad <strong>for</strong> a wide-ranging redrawing of the rules of commodities markets.<br />

On Sept. 25, 1990, a policy confirming that the Brent contracts were <strong>for</strong>ward contracts - <strong>and</strong> there<strong>for</strong>e,<br />

outside the scope of CFTC regulation - was put to a vote among CFTC commissioners.<br />

It passed 3 to 1.<br />

Ms. Gramm faced one vocal critic in her push to keep the Brent market unregulated: Fowler West, the<br />

lone 'no' vote.<br />

"It was the way we were doing it, the speed with which we were doing it," Mr. West recalled in an<br />

interview. "It was that kind of an attitude that did open the door up <strong>for</strong> a lot of problems."<br />

Ms. Gramm defends the CFTC's actions, <strong>and</strong> says the commission faced pressure from Congress to act.<br />

Senior CFTC staff, as well as a majority of commissioners, agreed with the interpretation concerning<br />

<strong>for</strong>ward contracts, she noted.<br />

"I don't think it was done too quickly," Ms. Gramm, who now chairs the Regulatory Studies Program at<br />

George Mason University's Mercatus Center, told The Globe <strong>and</strong> Mail in an interview.<br />

Mr. West, meanwhile, wasn't merely outvoted. He was muzzled.<br />

Although he wrote an official dissent after the vote, Ms. Gramm <strong>and</strong> the other commissioners blocked<br />

his views from being published in the CFTC's official record.<br />

Furious, Mr. West retaliated by voicing his concern about the CFTC's moves to the New York State<br />

Bar Association. The regulator, he told the lawyers' group, "may soon be paying a price <strong>for</strong> its<br />

politically expedient statutory interpretation. I doubt that its new <strong>for</strong>ward contract exemption can be<br />

restricted to large international oil <strong>and</strong> trading firms represented by influential lawyers."<br />

He concluded with an ominous warning: "The public, down the road, will suffer from <strong>this</strong> fit of<br />

deregulation, no matter how well intentioned."<br />

Mr. West's remarks were published in a law journal, <strong>and</strong> the ef<strong>for</strong>ts by the CFTC to quiet him stirred a<br />

furor in D.C. legal circles.<br />

Two years later, Congress amended the Commodity Exchange Act to require the CFTC to publish<br />

dissenting opinions.<br />

Into the promised l<strong>and</strong> of deregulation<br />

Much as Mr. West predicted, the Transnor case proved to be a watershed event. The CFTC's embrace<br />

of a narrow definition of a futures contract built on the regulator's earlier promise that it would not<br />

police swap transactions.<br />

Together, these moves opened up a new frontier of commodity trading, enabling financial speculators<br />

to buy <strong>and</strong> sell complex derivatives away from the prying eyes of regulators <strong>and</strong> exchanges.<br />

For these dealers in the late 1980s <strong>and</strong> 1990s, the shrinking CFTC rulebook created a "virtually<br />

regulation-free promised l<strong>and</strong>," Philip McBride Johnson, who was CFTC chairman from 1981 to 1983,<br />

later told a congressional committee.<br />

The vast majority of <strong>this</strong> trading boom occurred in the oil <strong>and</strong> energy markets, both of which are<br />

sufficiently large <strong>and</strong> liquid to accommodate legions of traders.<br />

It wasn't long be<strong>for</strong>e dealers began gravitating toward the smaller agricultural commodities markets as<br />

well.

To get exposure to a broad array of commodities, many institutional investors preferred to invest in an<br />

index that tracked the futures market. These indexes typically comprise a basket of products, from oil<br />

<strong>and</strong> gas to wheat, cotton, <strong>and</strong> precious metals, each given a weighting according to the size of its<br />

individual market.<br />

As funds began making more <strong>and</strong> more index investments, their ownership of food futures increased<br />

correspondingly.<br />

Yet the food markets are a somewhat different beast, with a different set of rules, <strong>and</strong> it wasn't long<br />

be<strong>for</strong>e <strong>this</strong> infusion of money hit another regulatory snag.<br />

For almost 75 years, the CFTC has imposed limits on how much of certain agricultural commodities,<br />

including wheat, cotton, soybean, soybean meal, corn, <strong>and</strong> oats, can be traded by non-commercial<br />

players - that is, investors who are not part of the food industry. So-called "commercial hedgers," like<br />

farmers or food processors, can trade unlimited amounts in order to manage their risk.<br />

The limits were designed to prevent manipulation <strong>and</strong> distortion in what are relatively small markets,<br />

<strong>and</strong> at the same time to allow <strong>for</strong> a small amount of speculative activity, in order to provide liquidity<br />

<strong>for</strong> trading.<br />

For decades, the restrictions didn't pose much of a problem. And then, in 1991, as new money began<br />

pouring in, the playing field suddenly shifted.<br />

Emboldened by the CFTC's laissez-faire approach, a bank approached the regulator <strong>and</strong>, <strong>for</strong> the first<br />

time, requested an exemption from speculative trading limits in an agricultural commodity.<br />

The unnamed bank was acting as a "swap dealer" <strong>for</strong> a pension fund: Essentially, it was a middleman<br />

who helped the pension fund get exposure to commodities. A spokesman <strong>for</strong> the regulator declined to<br />

identify the bank or the pension plan, citing confidentiality requirements.<br />

Underst<strong>and</strong>ing how a swap transaction like <strong>this</strong> works is critical to grasping why the CFTC ultimately<br />

granted an exemption to <strong>this</strong> bank - <strong>and</strong> in so doing, opened a loophole that has since allowed hundreds<br />

of billions of dollars worth of fund money to rush into the commodities markets.<br />

Let's say a pension fund wants to make a large investment in commodities, but the size of that<br />

investment would violate the trading limits on wheat. Rather than invest directly in the futures market,<br />

the fund can invest its money with a middleman, such as a bank, in what is called a swap transaction.<br />

The bank might agree to pay the fund a return on a commodity index - if the index rises 10 per cent in<br />

the next year, the bank will pay out that 10 per cent. But the bank doesn't want to be on the hook <strong>for</strong> 10<br />

per cent, so it hedges its risk by wading into the commodities market, <strong>and</strong> using the fund's money to<br />

buy futures. Essentially, it is buying futures to mirror the per<strong>for</strong>mance of the index, so that if prices<br />

rise, it can pass that gain along to the fund without digging into its own pocket.<br />

It is <strong>this</strong> notion of a middleman that swayed the CFTC. Had the pension fund invested all of its money<br />

directly in futures, it would not be allowed to exceed the trading threshold.<br />

But the swap dealer was a different story. The CFTC ruled that it was only buying futures to hedge its<br />

risk with the pension fund client; there<strong>for</strong>e, much like a food industry hedger, it deserved to be exempt<br />

too.<br />

The move was further evidence of the regulator's h<strong>and</strong>s-off approach under Ms. Gramm. Since that<br />

time, the regulator confirmed it has approved 20 additional exemptions <strong>for</strong> swap dealers, some of<br />

whom may strike agreements with multiple funds.<br />

"The underlying philosophy seemed to be that the big guy could take care of himself <strong>and</strong> there was no<br />

need <strong>for</strong> a lot of regulation," Mr. West recalled.

"It was actually told to me by the chairwoman that these [big companies] don't need us regulating them<br />

<strong>and</strong> hampering them, because they can take care of themselves. That missed the point. The point was,<br />

sure they can take care of themselves - but it wasn't them I was worried about."<br />

Still, despite <strong>this</strong> apparently favourable treatment, many swap dealers <strong>and</strong> derivatives traders remained<br />

nervous: Although the CFTC had provided welcome assurances, the regulator did not have the <strong>for</strong>mal<br />

power to enshrine these exemptions as binding rules.<br />

Brokerage firms, energy traders <strong>and</strong> other financial players aggressively lobbied Congress on the issue,<br />

<strong>and</strong> in 1992, the U.S. government passed new legislation that enabled the CFTC to determine which<br />

derivatives could be considered <strong>for</strong>ward contracts <strong>and</strong> receive exemptions.<br />

Armed with <strong>this</strong> new power, the CFTC quickly h<strong>and</strong>ed out nine different exemptions <strong>for</strong> certain energy<br />

contracts. One of the recipients was a Houston-based pipeline entity called Enron Corp. that was<br />

branching out into the energy trading arena.<br />

In January 1993, just as President Bill Clinton was being inaugurated, Ms. Gramm left the CFTC. Five<br />

weeks later she joined the board of Enron.<br />

Congress, however, wasn't done. In 2000, it introduced an array of exemptions, including one <strong>for</strong><br />

electronic trading of energy contracts. This new rule, which prompted the creation of numerous overthe-counter<br />

trading systems allowing buyers <strong>and</strong> sellers to avoid scrutiny, was later given a nickname:<br />

the Enron Loophole.<br />

Beyond the Enron Loophole<br />

Oddly enough, the CFTC's decision to exempt swap dealers from trading limits did not incite an<br />

immediate rush of fund money into agricultural commodities.<br />

Many pension plans, in particular, were still inherently conservative <strong>and</strong> viewed commodities as a<br />

high-risk playground better suited to speculators.<br />

One of the earliest funds to venture into commodities futures was the Ontario Teachers' Pension Plan. It<br />

began with a tentative $100-million (Canadian) investment in 1997, <strong>and</strong> is now one of the world's<br />

larger commodities investors, with about $3-billion committed.<br />

Not long after Teachers made its first commodities investment, Leo de Bever, then a vice-president<br />

with the fund, acknowledged in a speech at a New York conference that the strategy was<br />

unconventional <strong>for</strong> a fund like his. "We are probably an exception, rather than the rule in North<br />

America," he said.<br />

That didn't last long. Throughout the 1990s, pension funds from Japan to Canada began accumulating<br />

assets at a furious clip. Around the world, the bulging baby boom demographic was contributing record<br />

amounts of new money into pension plans <strong>and</strong> retirement funds. At the same time, pension funds were<br />

freed from the traditional shackles of fixed-income investments, like bonds, which produce low returns,<br />

<strong>and</strong> began depositing cash in stock markets, infrastructure <strong>and</strong> real estate.<br />

This boosted returns, <strong>and</strong> added further bulk to their growing assets. Worldwide institutional fund<br />

assets have soared from around $200-billion (U.S.) in 1980 to over $20-trillion today.<br />

But that growth didn't come without setbacks. The dot-com crash in 2001 wiped out billions of dollars<br />

worth of value, <strong>and</strong> offered a painful lesson in the need <strong>for</strong> further diversification. Suddenly,<br />

commodities emerged as a logical vehicle to help pension plans spread around their risk, <strong>and</strong> at the<br />

same time get a measure of protection against inflation.

It didn't hurt that when pension <strong>and</strong> index funds descended en masse into these markets, they found<br />

ready-made loopholes that enabled them to make much larger investments than they would otherwise<br />

have been able to.<br />

Consider the scale of the increase over the past seven years.<br />

In 2000, long-only speculative investors - that is, investors like these funds who are only betting that<br />

prices will climb higher - had committed about $4.7-billion to commodities, according to figures<br />

compiled by Gresham Investments, a New York firm specializing in commodities. That number has<br />

almost doubled every year since, hitting $80-billion in 2005, <strong>and</strong> $175-billion in 2007. As of today,<br />

most estimates peg total fund investment at approximately a quarter of a trillion dollars. Indeed, a study<br />

<strong>this</strong> month by Greenwich Associates found that almost 40 per cent of commodities investors have only<br />

been active in these markets <strong>for</strong> the past three years.<br />

Meanwhile, as <strong>this</strong> fund money stormed in <strong>and</strong> dem<strong>and</strong> rose, prices <strong>for</strong> a range of food staples, such as<br />

wheat, soybeans <strong>and</strong> corn, began escalating. Between 2000 <strong>and</strong> 2007, the price of wheat increased 147<br />

per cent on the Chicago Board of <strong>Trade</strong>. Over the same period, corn increased 79 per cent <strong>and</strong> soybeans<br />

72 per cent. In the past year, in particular, the price moves have been dramatic.The CFTC's moves to<br />

deregulate the sector, meanwhile, only inspired calls <strong>for</strong> more deregulation. As more funds piled in,<br />

stoking dem<strong>and</strong> <strong>for</strong> agricultural futures contracts, speculators began clamouring <strong>for</strong> more flexibility<br />

with trading limits.<br />

In 2005, the CFTC obliged by exp<strong>and</strong>ing trading limits on the amount of wheat, corn, oats <strong>and</strong><br />

soybeans that traders could buy or sell at any one time on the futures markets.<br />

Then, in 2006, Deutsche Bank <strong>and</strong> another undisclosed index fund operator asked the CFTC to exempt<br />

them from all trading limits, much as it had done <strong>for</strong> swap dealers.<br />

The CFTC didn't provide an outright exemption, but gave these two funds pretty much the same thing:<br />

a "no-action letter," assuring the funds that they would not be subject to penalties if they breached the<br />

limits.<br />

Last fall, after other funds began jockeying <strong>for</strong> similar treatment, the regulator issued a proposal to<br />

offer index <strong>and</strong> pension funds full exemptions, meaning they wouldn't have to go through a swap dealer<br />

to circumvent trading limits. The CFTC also asked <strong>for</strong> comments on a proposal to once again raise<br />

trading limits <strong>for</strong> speculative investors, such as hedge funds.<br />

For many in the food industry, who had begun to suspect a strong link between the market's wild<br />

swings <strong>and</strong> <strong>this</strong> influx of new fund money, <strong>this</strong> was the last straw.<br />

The One Hundred Years War<br />

On a Tuesday morning in late April, a group of more than 100 people shoehorned themselves into a<br />

cramped conference room in the Washington headquarters of the CFTC. There were farmers <strong>and</strong><br />

bakers, brokers <strong>and</strong> stock exchange officials, pension fund executives, professors, <strong>and</strong> even cotton<br />

growers, all convening <strong>for</strong> what was, by any measure, an extraordinary meeting: In the midst of<br />

skyrocketing prices <strong>for</strong> food <strong>and</strong> unheard of gyrations in futures contracts, the chief commodities<br />

regulator was trying to figure out whether the markets it oversees still worked properly.<br />

Almost immediately, fault lines emerged between the "commercial" players - farmers, grain elevators,<br />

processors, <strong>and</strong> anyone else directly involved in the food chain - <strong>and</strong> "speculators" - index funds,<br />

pension plans, hedge funds, <strong>and</strong> other investors who buy futures to bet on price movements, but who<br />

never intend to take physical possession of the commodity.

One by one, the commercials took their turn at the microphone, ticking off a laundry list of grievances:<br />

Prices were moving too quickly <strong>and</strong> unpredictably; grain elevators were at their credit limit, depriving<br />

farmers of a primary source of hedging risk.<br />

And, <strong>for</strong> some mysterious reason, the price of the futures contract was not converging with the<br />

underlying price of the cash commodity it represented when that contract drew close to expiration.<br />

Can a market be trusted if prices soar the same day reports come out showing that there is an<br />

oversupply of that product, they asked. Is the market sound when prices shoot up 85 per cent in a<br />

matter of days <strong>and</strong> then fall back down again <strong>for</strong> no apparent reason? Almost to a person, these<br />

commercials laid a large portion of the blame at the feet of investment funds, particularly the pensions<br />

<strong>and</strong> indexers who are able to skirt trading limits.<br />

Many in the food industry complained that these index funds don't behave like traditional speculators in<br />

commodity markets. Unlike hedge funds, which actively buy <strong>and</strong> sell contracts, <strong>and</strong> make bets on price<br />

increases <strong>and</strong> decreases, index funds are passive investors. They take positions in various commodities<br />

<strong>and</strong> hang on <strong>for</strong> extended periods, betting that prices will continue to go up. Critics claim that <strong>this</strong> has<br />

resulted in a kind of hoarding, <strong>and</strong> that the market no longer reacts the way it should to supply <strong>and</strong><br />

dem<strong>and</strong> factors.<br />

"It's the National Corn Growers Association's opinion that large funds have an overwhelming influence<br />

in these markets," Gary Niemeyer, a representative <strong>for</strong> the NCGA, told the roundtable. "This thing is<br />

just getting totally out of h<strong>and</strong>. The money is unreal."<br />

Few were more pointed in their criticisms than the cotton growers. Cotton isn't part of the global food<br />

crisis, nor is it suffering from diminished supplies. Yet in one 90-minute stretch <strong>this</strong> spring, the futures<br />

<strong>for</strong> <strong>this</strong> commodity jumped a full 25 per cent, confounding just about everyone in the industry.<br />

Cotton volatility was held up as one of the clearest signs to date that soft commodity prices have<br />

become unhinged from market fundamentals, <strong>and</strong> may instead be reacting to the moves of large fund<br />

traders.<br />

"This makes no sense," complained Billy Dunavunt, the long-time chairman of Dunavunt Enterprises,<br />

<strong>and</strong> the closest thing to a living legend the industry possesses. "The market is broken, it's out of whack,<br />

<strong>and</strong> someone has got to step in <strong>and</strong> give some relief."<br />

The funds, not surprisingly, dismissed these charges as baseless, <strong>and</strong> argued their involvement added<br />

liquidity to the market, enabling farmers <strong>and</strong> food producers to offload unwanted risk.<br />

"I did not see a convincing case that index money has changed the stated objectives of <strong>this</strong> market,"<br />

insisted Bob Grier, a fund manager at Pimco, one of the biggest players in the agricultural commodities<br />

market.<br />

The odd thing is, <strong>this</strong> meeting could have occurred 150 years ago, <strong>and</strong> it wouldn't have seemed out of<br />

place.<br />

The modern-day commodities market was born in 1848, when 82 merchants b<strong>and</strong>ed together to create<br />

the Chicago Board of <strong>Trade</strong>. Until that point, the grain trade was unpredictable, at best, <strong>and</strong> utter chaos,<br />

at worse.<br />

Buying did not take place in any organized fashion, <strong>and</strong> individual farmers tended to transact with<br />

separate parties, leading to wide discrepancies in pricing. Because farmers typically sold their wares<br />

after harvest, the glut of grain often resulted in low prices.<br />

Chicago, with its nascent railway lines <strong>and</strong> proximity to the Great Lakes <strong>and</strong> Midwestern farming<br />

country, was a natural place to bring everyone together. For the first time, farmers could manage their

isk in a systematic way: They would agree with a buyer to deliver grain, at some specific date in the<br />

future, at a specific price.<br />

This was a <strong>for</strong>ward contract. But it wasn't until almost 20 years later, in 1865, that a proper futures<br />

market took shape.<br />

So popular did these contracts become in the late 19th century that hundreds of exchanges began<br />

popping up across the United States, specializing in everything from butter <strong>and</strong> eggs to wheat, cotton<br />

<strong>and</strong> livestock.<br />

Soon, speculators began to pour into the market, making bets on whether commodities would rise or<br />

fall in value. They never had to take possession of the commodity, but could buy a future at one price,<br />

<strong>and</strong> then sell it days, weeks, or months later.<br />

Almost from the start, there was controversy. "There was an orgy of speculation <strong>and</strong> market<br />

manipulation during the Civil War," Dan Morgan wrote in his book the Merchants of Grain. "The<br />

Board printed rules governing trading in 1869, but abuses of all kinds continued - fraud, bribery of<br />

telegraph operators to obtain confidential in<strong>for</strong>mation (until coded messages were used), <strong>and</strong> the<br />

spreading of false rumours to influence prices. Outside the trading floor at Jackson <strong>and</strong> La Salle streets,<br />

bucket shops, not much different from bookie joints or other gambling establishments, flourished."<br />

In Canada, meanwhile, farmers were so upset they pushed the government to create a national cooperative<br />

in order to avoid selling grain through futures markets altogether. Those ef<strong>for</strong>ts led to the<br />

<strong>for</strong>mation of the Canadian Wheat Board in 1935.<br />

Even today, North American farmers view speculators as gamblers, exchanging pieces of paper in<br />

hopes that prices will move the way they want them to, but never getting their h<strong>and</strong>s dirty with the<br />

physical product.<br />

Yet, despite <strong>this</strong> uneasy symbiosis, most would agree that speculation per<strong>for</strong>ms a vital role in the<br />

markets: If farmers or food producers want to hedge against their risk by selling a futures contract -<br />

say, to deliver wheat a year from now at $8 a bushel - they need speculators who are willing to buy the<br />

contract in a bet that prices will rise by the delivery date.<br />

The question, going back to the infancy of the markets, was one of balance: How much speculation was<br />

necessary to allow the markets to function smoothly?<br />

After the First World War, when wheat prices plunged, the farming industry blamed the speculators,<br />

accusing them of using short-selling tactics to drive down the market. Widespread instances of market<br />

manipulation, meanwhile, incited Congress to introduce bills attempting to eliminate futures trading<br />

altogether.<br />

Although they were narrowly defeated, problems in the market highlighted the need <strong>for</strong> improved<br />

regulation, leading first to the Grain Futures Act of 1922, <strong>and</strong> then to the Commodities Exchange Act<br />

of 1936. The latter exp<strong>and</strong>ed the scope of regulation to cover other commodities, including cotton, <strong>and</strong><br />

<strong>for</strong> the first time imposed limits on speculators to prevent manipulation or distortion of the market.<br />

In other words, non-commercial traders in the futures market could only buy a certain amount of wheat,<br />

corn <strong>and</strong> other products covered under the act.<br />

The measures were put in place to protect farmers, who have a couple of ways to manage their risk:<br />

They can participate directly in the futures market, or they can enter into a <strong>for</strong>ward contract with a<br />

grain elevator, who promises to buy their crop at a certain price. (Canadian farmers sell most of their<br />

wheat through the wheat board, but they use a similar system <strong>for</strong> selling other crops, including canola).

Directly trading in futures isn't all that popular <strong>for</strong> farmers, owing both to the complexity of the futures<br />

market <strong>and</strong> the capital required to manage a trading position.<br />

Most farmers, like Mr. Giessel in Kansas, choose to enter <strong>for</strong>ward contracts with grain elevators. Last<br />

September, <strong>for</strong> instance, he struck an agreement with a local co-op to sell a third of his 2008 wheat<br />

crop at $5.30 a bushel: a price that looked good at the time, <strong>and</strong> that looked horrible in the spring, when<br />

wheat moved close to $13. The grain elevator, once armed with <strong>this</strong> agreement, immediately sells<br />

futures in the market at roughly the same price to minimize its risk.<br />

But here's the rub: Every time the futures price rises, the elevator must post an equivalent amount of<br />

money in the <strong>for</strong>m of margin - a kind of goodwill bond in case the farmer has a problem delivering the<br />

physical crop.<br />

That's fine if the price of wheat nudges up a few nickels. But when an elevator sells a futures contract<br />

at $6 a bushel, <strong>and</strong> that price doubles, it must then post an additional $6 worth of margin on every<br />

bushel. That means going to the bank <strong>for</strong> a very big loan, which is easier said than done in today's<br />

credit environment.<br />

"A year ago, we're sitting here with a $7-million line of credit," said Kim Barnes, a hulking man who<br />

works as an assistant manager with the Pawnee County Co-op. "Now it's over $19.5-million. And our<br />

interest costs have gone from $7-million last year to $14-million <strong>this</strong> year. Last year, because we were<br />

in uncharted waters, the banks allowed you to come back to the well. But we've all been told <strong>this</strong> year<br />

that you've got to live within your means."<br />

Translation? Most elevators will only accept futures contracts <strong>for</strong> <strong>this</strong> year, <strong>and</strong> won't offer contracts to<br />

farmers looking to lock in prices <strong>for</strong> their 2009 or 2010 crop, depriving them of a common risk<br />

management tool. Some elevators are only offering contracts 60 days out, while a few unlucky ones<br />

have fallen into insolvency, unable to meet margin calls as prices accelerated to record levels.<br />

As if <strong>this</strong> unpredictability weren't bad enough, key input costs like fertilizer, fuel <strong>and</strong> herbicide have<br />

soared, affecting farmers on both sides of the border. These inputs are a bit like taxes: Once they go up,<br />

they stay up, regardless of whether commodity prices fall again, as they have already done in the wheat<br />

market. That can take a big bite out of profit if the commodities don't remain at their current high<br />

levels.<br />

For farmers, <strong>this</strong> sudden unpredictability is proof that commodities markets are no longer doing what<br />

they were supposed to do. "The commodity market was designed to provide a <strong>for</strong>ward pricing tool to<br />

protect ourselves," said Ian Wishart, a farmer in western Manitoba, "not to provide an opportunity <strong>for</strong><br />

someone else to make profits."<br />

In the lead up to the April meeting in Washington, the CFTC resisted the idea that ballooning fund<br />

investments were responsible <strong>for</strong> the dramatic upswing in commodity prices.<br />

Yet given the outpouring of concern from farmers, the regulator wasn't taking any chances. At the<br />

meeting, acting chairman Walt Lukken said the CFTC would temporarily shelve plans to move ahead<br />

with two proposals: Raising the limits, once again, <strong>for</strong> speculative traders like hedge funds, <strong>and</strong><br />

<strong>for</strong>malizing an exemption from any trading limits <strong>for</strong> index funds.<br />

"I will be very cautious about moving <strong>for</strong>ward with such initiatives at <strong>this</strong> time," Mr. Lukken said. "I<br />

believe that be<strong>for</strong>e acting, <strong>this</strong> agency must be certain that additional speculative pressures will not<br />

exacerbate the anomalies we are experiencing in these markets."<br />

All Roads Lead to Rome

Next week, international leaders will gather in Rome <strong>for</strong> the High-Level Conference on World Food<br />

Security, hosted by the UN Food <strong>and</strong> <strong>Agriculture</strong> Organization, in an ef<strong>for</strong>t to bring the spiralling food<br />

crisis under control.<br />

In a report leading up to the summit, the UN warned that 22 countries, including Eritrea, Niger,<br />

Comoros, Haiti <strong>and</strong> Liberia, are particularly vulnerable to the recent rise in food prices, <strong>and</strong> the agency<br />

is calling <strong>for</strong> urgent measures to ensure the world's poorest citizens have af<strong>for</strong>dable access to food.<br />

The UN has also acknowledged that the speculative money flowing into commodities markets could be<br />

wreaking havoc with prices, joining officials from other international bodies, including the World<br />

Bank, in drawing attention to the problem.<br />

In the face of stiff criticism from U.S. agriculture <strong>and</strong> <strong>this</strong> widening concern abroad, current <strong>and</strong> <strong>for</strong>mer<br />

CFTC officials have insisted the massive movement of investors into commodities has not distorted the<br />

markets.<br />

Ms. Gramm claimed that deregulation <strong>and</strong> changes to the futures market have nothing to do with<br />

today's rising food prices. That notion, she said, "is just plain flat wrong."<br />

"Volatility in the futures market doesn't cause prices [to rise]," she said. "Futures markets are an<br />

indicator of what's going on in the cash market, not vice versa."<br />

Senator Carl Levin, a Michigan Democrat who heads a subcommittee that is probing commodities<br />

prices, disputes <strong>this</strong> point of view. The CFTC, he said <strong>this</strong> week, hasn't addressed the issue of how <strong>this</strong><br />

influx of money into futures markets has affected price.<br />

"You monitor, you update, you study, <strong>and</strong> then you don't do a darn thing about it," Mr. Levin said.<br />

Amid <strong>this</strong> controversy, there remains a growing sense that the CFTC will have to implement some<br />

measure of added regulation to address concerns about soaring prices.<br />

In the aftermath of the subprime mortgage debacle, U.S. lawmakers are trying to usher in a new era of<br />

regulation <strong>and</strong> scrutiny - one that dem<strong>and</strong>s far greater transparency on exotic derivative instruments,<br />

whether they be tied to the housing bubble or the commodities markets.<br />

This month, the Senate passed legislation aimed at closing the Enron loopholes <strong>and</strong> bringing electronic<br />

energy trading under the purview of the CFTC. Facing growing pressure to rein in soaring prices, the<br />

CFTC announced Thursday that it is investigating possible manipulation of crude oil prices by traders.<br />

More than one farmer has pointed to the Federal Reserve's assistance in helping JPMorgan to buy<br />

troubled brokerage firm Bear Stearns, <strong>and</strong> openly wondered why the U.S. government couldn't make a<br />

similar intervention in the food market. Many would say the stakes are higher, <strong>and</strong> carry with them<br />

something of a moral obligation.<br />

"The tsunami they refer to as the food crisis should be the wake-up call to all of us that we have to get<br />

our priorities right," said Diana Klemme, a vice-president <strong>and</strong> grain division director at Grain Service<br />

Corp., an Atlanta firm that advises farmers on risk management.<br />

"It's not just about the Kansas wheat crop, or the Iowa corn crop," she said. "This is about the world.<br />

And it's hard <strong>for</strong> us to step back <strong>and</strong> say we have to put <strong>this</strong> in context."<br />

Even farmers like Mr. Giessel, preoccupied as they are with pressing concerns at home, readily<br />

acknowledge that the problems with commodities trading resonate far beyond the heartl<strong>and</strong>.<br />

"We're commoditizing everything, <strong>and</strong> losing sight that it's food, that it's something people need," he<br />

said. "We're trading lives."<br />

TIMELINE

1848<br />

82 businessmen <strong>for</strong>m the Chicago Board of <strong>Trade</strong> (CBOT) <strong>for</strong> producers, buyers <strong>and</strong> sellers of grain.<br />

1865<br />

CBOT develops futures contracts <strong>for</strong> grains. Hundreds of other futures markets spring up across the<br />

U.S., including the Butter <strong>and</strong> Cheese Exchange in New York (which later became the New York<br />

Mercantile Exchange) <strong>and</strong> Chicago Butter <strong>and</strong> Egg Board (later changed to Chicago Mercantile<br />

Exchange).<br />

1887<br />

Winnipeg Grain <strong>and</strong> Produce Exchange founded (renamed Winnipeg Commodity Exchange in 1972).<br />

Operated as a cash market only <strong>for</strong> the first 18 years be<strong>for</strong>e becoming a futures market.<br />

1905<br />

Grain Growers Grain Co. Ltd. created in Saskatchewan as a co-operative <strong>for</strong> farmers.<br />

1917<br />

Wheat futures trading suspended on the Winnipeg exchange, leading the federal government to create<br />

the Canadian Wheat Board two years later.<br />

1920<br />

Canadian Wheat Board disb<strong>and</strong>ed.<br />

1922<br />

U.S. passes Grain Futures Act in response to widespread manipulation in the futures markets. The law<br />

cracked down on "excessive speculation" <strong>and</strong> established a framework <strong>for</strong> regulated commodity<br />

exchanges.<br />

1923<br />

Wheat pools created in Alberta, Saskatchewan <strong>and</strong> Manitoba to market grain <strong>for</strong> farmers.<br />

1935<br />

Canadian Wheat Board re-established by the federal government to market grain.<br />

1936<br />

U.S. enacts Commodity Exchange Act to broaden regulations to include trading in other agricultural<br />

commodities, including cotton, butter <strong>and</strong> eggs.<br />

1943<br />

The CWB is granted a monopoly to sell prairie farmer's wheat; wheat trading on the Winnipeg<br />

exchange suspended.<br />

1958<br />

Agricultural Stabilization Board created in Canada to provide price support to farmers in various<br />

commodities.<br />

1972<br />

Farm Products Marketing Agencies Act enacted in Canada, leads to the creation of marketing boards<br />

<strong>for</strong> dairy <strong>and</strong> poultry products.

1974<br />

U.S. government creates the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) to regulate commodity<br />

exchanges.<br />

1989<br />

CFTC issues a "swaps policy statement," saying it would not seek to regulate over-the-counter swap<br />

transactions.<br />

1990<br />

Transnor decision prompts CFTC to rule that Brent North Sea contracts are <strong>for</strong>ward contracts <strong>and</strong> not<br />

subject to regulation.<br />

1997<br />

Ontario Teachers' Pension Plan becomes one of the first pension plans to invest in commodities, with a<br />

$100-million investment.<br />

2000<br />

Commodity Futures Modernization Act in the U.S. codifies exemptions <strong>and</strong> exclusions <strong>for</strong> various<br />

energy <strong>and</strong> financial derivatives from CFTC oversight.<br />

Intercontinental Exchange created in Atlanta as an electronic energy trading plat<strong>for</strong>m.<br />

2005<br />

CFTC exp<strong>and</strong>s position limits in wheat, corn <strong>and</strong> soybean trading <strong>for</strong> speculators.<br />

2006<br />

CFTC grants index funds exemptions from position limits imposed on speculators.<br />

2008<br />

In February, prices <strong>for</strong> some wheat contracts surge 85 per cent on Minneapolis Grain Exchange.<br />

Trading is so heavy the contract hits daily limits 12 times, <strong>for</strong>cing the exchange to exp<strong>and</strong> them.<br />

Paul Waldie