Applications of Braid Theory

Applications of Braid Theory

Applications of Braid Theory

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

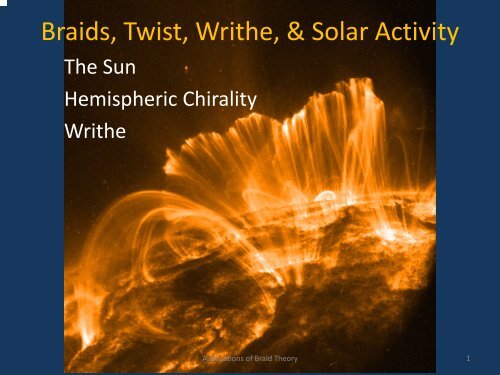

<strong>Braid</strong>s, Twist, Writhe, & Solar Activity<br />

The Sun<br />

Hemispheric Chirality<br />

Writhe<br />

<strong>Applications</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Braid</strong> <strong>Theory</strong> 1

Coronal Heating<br />

Parker model (1983): The interior structure t re <strong>of</strong><br />

coronal loops is braided.<br />

When neighbouring tubes are misaligned by<br />

~ 30 degrees, reconnection removes a<br />

crossing, releasing magnetic energy into<br />

heat – a nan<strong>of</strong>lare.<br />

Linton, Dahlburg and Antiochos 2001<br />

<strong>Applications</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Braid</strong> <strong>Theory</strong> 2

Hemispheric Chirality<br />

Sunspot whorls<br />

Filaments<br />

<strong>Applications</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Braid</strong> <strong>Theory</strong> 3

Coronal Magnetic Structures <strong>of</strong>ten display kinked<br />

or helical structure ….<br />

Yohkoh s<strong>of</strong>t x-ray image<br />

<strong>of</strong> Southern hemisphere<br />

sigmoid<br />

X‐Ray Bi Brightenings i (Sigmoids) id

For closed curves and fields:<br />

Magnetic Helicity<br />

1. For two linked torii <strong>of</strong> flux F 1 and F 2 , and internal twists T 1 and T 2<br />

2. Helicity is an ideal MHD invariant.<br />

<strong>Applications</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Braid</strong> <strong>Theory</strong> 5

Magnetic Helicity <strong>of</strong> a subvolume <strong>of</strong> space<br />

<strong>Applications</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Braid</strong> <strong>Theory</strong> 6

global and regional helicities<br />

Let space be divided into N regions. Let H i be the helicity in region i (relative to vacuum<br />

field). Then for regions separated by parallel planes or concentric spheres,

Helicity between two planes can be expressed as a sum<br />

<strong>of</strong> winding numbers, over all pairs <strong>of</strong> field lines:

What if curves go up and down?<br />

1. Cut the curves into segments at turning points<br />

in height.<br />

2. Sum winding numbers for each<br />

pair <strong>of</strong> segments (if opposite<br />

directions, multiply by ‐1).<br />

Heresegments2and3give<br />

Here segments 2 and 3 give<br />

winding angle <strong>of</strong> ‐4p.

Solar Helicity Observations<br />

Current helicity j z /B z from vector magnetograms<br />

(Abramenko et al 1997; Pevtsov & Latushko 2002)<br />

Effects <strong>of</strong> differential rotation on active regions (van<br />

Ballegooijen et al 1998; B & Ruzmaikin 2000; Devore 2000; Green et al<br />

2002; Nindos et al 2003)<br />

Helicity flow through photosphere (Kusano et al 2002; Tian<br />

2003; Démoulin & B 2003; Chae et al 2004; Kusano et al 2005; Pariat et al<br />

2006; Longcope 2007)<br />

Magnetograms plus best‐fit force‐free free extrapolations<br />

(Démoulin et al 2002; Aulanier et al 2002, 2005)

Sigmoids<br />

S<strong>of</strong>t X‐ray brightenings g first<br />

identified in Yohkoh (Rust &<br />

Kumar 1996).<br />

Most (91%) active regions<br />

containing sigmoids also<br />

display filaments (Pevtsov<br />

2002).<br />

Sigmoids are mostly S shaped in the South and<br />

shaped in the North

Sigmoids are <strong>of</strong>ten precursors <strong>of</strong><br />

Coronal Mass Ejections

Flux Tube Models<br />

Twisted Flux tubes have <strong>of</strong>ten been used in models <strong>of</strong> solar<br />

filaments and Coronal Mass Ejections. Could the Sigmoid x‐ray<br />

brightenings show the shape <strong>of</strong> these tubes?<br />

Low & Berger 2003: magnetostatic solutions with<br />

helical symmetry embedded in external field<br />

Unfortunately, these give<br />

the wrong sign! However,<br />

surrounding current<br />

concentrations can have the<br />

correct sign.

Sideways helical tubes? No! the sign is<br />

wrong! shape for positive helicity<br />

– opposite to hemispheric law.

(2004, 2005)<br />

Kliem & Török simulation<br />

Follow nonlinear evolution <strong>of</strong> kink<br />

instability in Titov – Démoulin model<br />

‐‐‐ Intense currents develop along field<br />

Intense currents develop along field<br />

lines below flux tube which resemble<br />

sigmoids <strong>of</strong> the correct sign.

Gibson & Fan model

Linking, Twist, and Writhe<br />

Calugareanu 1961: Linking number = Twist + Writhe

For closed curves:<br />

Writhe

A trefoil knot and its tantrix curve<br />

Let A = the area enclosed by the tantrix curve.<br />

Then<br />

(Fuller 1971)

Writhe (by popular belief)<br />

Kink instability: internal twist converted to writhe<br />

(Ricca & M<strong>of</strong>fatt 1995, Rust 1996)<br />

Stretch‐Twist‐Fold Dynamos: large scale positive<br />

writhe helicity, small scale negative twist helicity<br />

(Gilbert 2003)<br />

Outer Convection Zone: coriolis force on rising<br />

tubes creates large scale positive writhe helicity,<br />

small scale negative twist helicity (in North)<br />

– ‘bihelical fields’ (Blackman & Brandenburg)<br />

– S effect (Longcope & Pevtsov): helicity source in active<br />

regions?

Helicity Decomposition<br />

Magnetic Helicity for (thin) closed flux tube with axial<br />

flux Φ:<br />

But how do we define the writhe <strong>of</strong> a curve with<br />

endpoints on a boundary plane (or boundary<br />

sphere)?

Answer: write the writhe <strong>of</strong> a framed curve as the<br />

difference between winding number and twist <strong>of</strong> the<br />

curves on the tube.<br />

When averaged over the<br />

tube, this is independent<br />

<strong>of</strong> framing.<br />

<strong>Applications</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Braid</strong> <strong>Theory</strong> 22

This methods divides up a curve into pieces at its maxima and<br />

minima, then computes the “local writhe” <strong>of</strong> each piece<br />

(winding – twist), and the “nonlocal writhes” (just winding)<br />

between pieces. Total writhe = ‐0.752<br />

local writhe<br />

= 0.374<br />

Nonlocal writhe = ‐1.5<br />

local writhe<br />

= 0.374

Example: the tangent to a vertical helix has constant<br />

latitude<br />

The local writhe term equals the area<br />

The local writhe term equals the area<br />

between the tantrix curve and the North pole

Writhe can also be defined for loops by extending the<br />

loop and calculating the corresponding enclosed tantrix<br />

area (same results!)

Normal and Anomalous writhe<br />

How an elastic rod buckles:<br />

Normally,<br />

Negative twist S shape (as seen from above)<br />

Positive twist shape<br />

Solar sigmoids:<br />

Two positive twist sigmoids<br />

anomalous!

Kinked Loop: Sine Height pr<strong>of</strong>ile<br />

heig ght<br />

Sine height pr<strong>of</strong>ile z ∼ SinHπ tL<br />

0.4<br />

0.3<br />

0.2<br />

0.1<br />

0<br />

0 0.2 0.4 0.6 0.8 1<br />

horizontal position<br />

Twisted Sine Shape<br />

0.3<br />

0.2<br />

0.1<br />

Writh he<br />

0<br />

−0.1<br />

−0.2<br />

−0.3<br />

Q=-pê2<br />

Q=-3pê8<br />

Q=-pê4ê<br />

Q=-pê8<br />

0 0.2 0.4 0.6 0.8 1<br />

height Hunits <strong>of</strong> footpoint separationL<br />

h=0.4 Ө = ‐π/4

Two loops with identical Writhe = ‐0.2<br />

Normal<br />

Anomalous<br />

Sigmoids on the sun seem to be <strong>of</strong> the anomalous type