addressing gender-based violence through usaid's health ... - IGWG

addressing gender-based violence through usaid's health ... - IGWG

addressing gender-based violence through usaid's health ... - IGWG

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

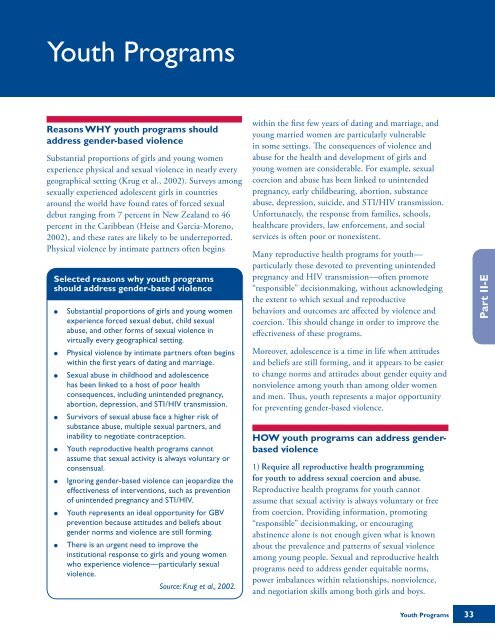

Youth Programs<br />

Reasons WHY youth programs should<br />

address <strong>gender</strong>-<strong>based</strong> <strong>violence</strong><br />

Substantial proportions of girls and young women<br />

experience physical and sexual <strong>violence</strong> in nearly every<br />

geographical setting (Krug et al., 2002). Surveys among<br />

sexually experienced adolescent girls in countries<br />

around the world have found rates of forced sexual<br />

debut ranging from 7 percent in New Zealand to 46<br />

percent in the Caribbean (Heise and Garcia-Moreno,<br />

2002), and these rates are likely to be underreported.<br />

Physical <strong>violence</strong> by intimate partners often begins<br />

Selected reasons why youth programs<br />

should address <strong>gender</strong>-<strong>based</strong> <strong>violence</strong><br />

●<br />

●<br />

●<br />

●<br />

●<br />

●<br />

●<br />

●<br />

Substantial proportions of girls and young women<br />

experience forced sexual debut, child sexual<br />

abuse, and other forms of sexual <strong>violence</strong> in<br />

virtually every geographical setting.<br />

Physical <strong>violence</strong> by intimate partners often begins<br />

within the first years of dating and marriage.<br />

Sexual abuse in childhood and adolescence<br />

has been linked to a host of poor <strong>health</strong><br />

consequences, including unintended pregnancy,<br />

abortion, depression, and STI/HIV transmission.<br />

Survivors of sexual abuse face a higher risk of<br />

substance abuse, multiple sexual partners, and<br />

inability to negotiate contraception.<br />

Youth reproductive <strong>health</strong> programs cannot<br />

assume that sexual activity is always voluntary or<br />

consensual.<br />

Ignoring <strong>gender</strong>-<strong>based</strong> <strong>violence</strong> can jeopardize the<br />

effectiveness of interventions, such as prevention<br />

of unintended pregnancy and STI/HIV.<br />

Youth represents an ideal opportunity for GBV<br />

prevention because attitudes and beliefs about<br />

<strong>gender</strong> norms and <strong>violence</strong> are still forming.<br />

There is an urgent need to improve the<br />

institutional response to girls and young women<br />

who experience <strong>violence</strong>—particularly sexual<br />

<strong>violence</strong>.<br />

Source: Krug et al., 2002.<br />

within the first few years of dating and marriage, and<br />

young married women are particularly vulnerable<br />

in some settings. The consequences of <strong>violence</strong> and<br />

abuse for the <strong>health</strong> and development of girls and<br />

young women are considerable. For example, sexual<br />

coercion and abuse has been linked to unintended<br />

pregnancy, early childbearing, abortion, substance<br />

abuse, depression, suicide, and STI/HIV transmission.<br />

Unfortunately, the response from families, schools,<br />

<strong>health</strong>care providers, law enforcement, and social<br />

services is often poor or nonexistent.<br />

Many reproductive <strong>health</strong> programs for youth—<br />

particularly those devoted to preventing unintended<br />

pregnancy and HIV transmission—often promote<br />

“responsible” decisionmaking, without acknowledging<br />

the extent to which sexual and reproductive<br />

behaviors and outcomes are affected by <strong>violence</strong> and<br />

coercion. This should change in order to improve the<br />

effectiveness of these programs.<br />

Moreover, adolescence is a time in life when attitudes<br />

and beliefs are still forming, and it appears to be easier<br />

to change norms and attitudes about <strong>gender</strong> equity and<br />

non<strong>violence</strong> among youth than among older women<br />

and men. Thus, youth represents a major opportunity<br />

for preventing <strong>gender</strong>-<strong>based</strong> <strong>violence</strong>.<br />

HOW youth programs can address <strong>gender</strong><strong>based</strong><br />

<strong>violence</strong><br />

1) Require all reproductive <strong>health</strong> programming<br />

for youth to address sexual coercion and abuse.<br />

Reproductive <strong>health</strong> programs for youth cannot<br />

assume that sexual activity is always voluntary or free<br />

from coercion. Providing information, promoting<br />

“responsible” decisionmaking, or encouraging<br />

abstinence alone is not enough given what is known<br />

about the prevalence and patterns of sexual <strong>violence</strong><br />

among young people. Sexual and reproductive <strong>health</strong><br />

programs need to address <strong>gender</strong> equitable norms,<br />

power imbalances within relationships, non<strong>violence</strong>,<br />

and negotiation skills among both girls and boys.<br />

Part II-E<br />

Youth Programs<br />

33