Culture and the Self: Implications for Cognition, Emotion, and ... - iacmr

Culture and the Self: Implications for Cognition, Emotion, and ... - iacmr

Culture and the Self: Implications for Cognition, Emotion, and ... - iacmr

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

CULTURE AND THE SELF 243<br />

14 r-<br />

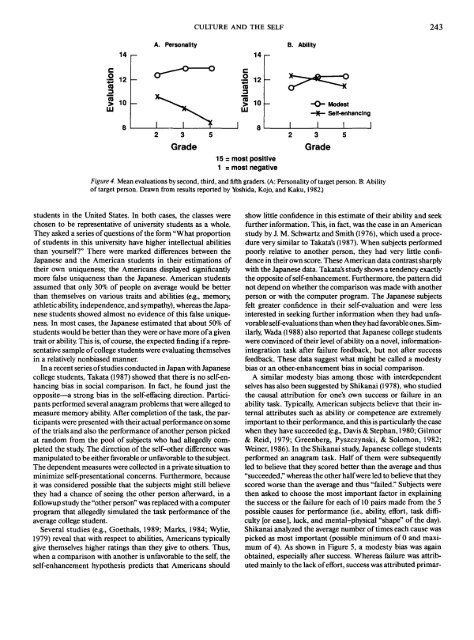

A. Personality B. Ability<br />

14 r-<br />

CO<br />

"ca<br />

10<br />

I «<br />

CO<br />

I 10<br />

Ul<br />

-O- Modest<br />

—K— <strong>Self</strong>-enhancing<br />

I I I<br />

Grade<br />

15 = most positive<br />

1 = most negative<br />

Grade<br />

Figure 4. Mean evaluations by second, third, <strong>and</strong> fifth graders. (A: Personality of target person. B: Ability<br />

of target person. Drawn from results reported by Yoshida, Kojo, <strong>and</strong> Kaku, 1982.)<br />

students in <strong>the</strong> United States. In both cases, <strong>the</strong> classes were<br />

chosen to be representative of university students as a whole.<br />

They asked a series of questions of <strong>the</strong> <strong>for</strong>m "What proportion<br />

of students in this university have higher intellectual abilities<br />

than yourself?" There were marked differences between <strong>the</strong><br />

Japanese <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> American students in <strong>the</strong>ir estimations of<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir own uniqueness; <strong>the</strong> Americans displayed significantly<br />

more false uniqueness than <strong>the</strong> Japanese. American students<br />

assumed that only 30% of people on average would be better<br />

than <strong>the</strong>mselves on various traits <strong>and</strong> abilities (e.g., memory,<br />

athletic ability, independence, <strong>and</strong> sympathy), whereas <strong>the</strong> Japanese<br />

students showed almost no evidence of this false uniqueness.<br />

In most cases, <strong>the</strong> Japanese estimated that about 50% of<br />

students would be better than <strong>the</strong>y were or have more of a given<br />

trait or ability. This is, of course, <strong>the</strong> expected finding if a representative<br />

sample of college students were evaluating <strong>the</strong>mselves<br />

in a relatively nonbiased manner.<br />

In a recent series of studies conducted in Japan with Japanese<br />

college students, Takata (1987) showed that <strong>the</strong>re is no self-enhancing<br />

bias in social comparison. In fact, he found just <strong>the</strong><br />

opposite—a strong bias in <strong>the</strong> self-effacing direction. Participants<br />

per<strong>for</strong>med several anagram problems that were alleged to<br />

measure memory ability. After completion of <strong>the</strong> task, <strong>the</strong> participants<br />

were presented with <strong>the</strong>ir actual per<strong>for</strong>mance on some<br />

of <strong>the</strong> trials <strong>and</strong> also <strong>the</strong> per<strong>for</strong>mance of ano<strong>the</strong>r person picked<br />

at r<strong>and</strong>om from <strong>the</strong> pool of subjects who had allegedly completed<br />

<strong>the</strong> study. The direction of <strong>the</strong> self-o<strong>the</strong>r difference was<br />

manipulated to be ei<strong>the</strong>r favorable or unfavorable to <strong>the</strong> subject.<br />

The dependent measures were collected in a private situation to<br />

minimize self-presentational concerns. Fur<strong>the</strong>rmore, because<br />

it was considered possible that <strong>the</strong> subjects might still believe<br />

<strong>the</strong>y had a chance of seeing <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r person afterward, in a<br />

followup study <strong>the</strong> "o<strong>the</strong>r person" was replaced with a computer<br />

program that allegedly simulated <strong>the</strong> task per<strong>for</strong>mance of <strong>the</strong><br />

average college student.<br />

Several studies (e.g., Goethals, 1989; Marks, 1984; Wylie,<br />

1979) reveal that with respect to abilities, Americans typically<br />

give <strong>the</strong>mselves higher ratings than <strong>the</strong>y give to o<strong>the</strong>rs. Thus,<br />

when a comparison with ano<strong>the</strong>r is unfavorable to <strong>the</strong> self, <strong>the</strong><br />

self-enhancement hypo<strong>the</strong>sis predicts that Americans should<br />

show little confidence in this estimate of <strong>the</strong>ir ability <strong>and</strong> seek<br />

fur<strong>the</strong>r in<strong>for</strong>mation. This, in fact, was <strong>the</strong> case in an American<br />

study by J. M. Schwartz <strong>and</strong> Smith (1976), which used a procedure<br />

very similar to Takata's (1987). When subjects per<strong>for</strong>med<br />

poorly relative to ano<strong>the</strong>r person, <strong>the</strong>y had very little confidence<br />

in <strong>the</strong>ir own score. These American data contrast sharply<br />

with <strong>the</strong> Japanese data. Takata's study shows a tendency exactly<br />

<strong>the</strong> opposite of self-enhancement. Fur<strong>the</strong>rmore, <strong>the</strong> pattern did<br />

not depend on whe<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong> comparison was made with ano<strong>the</strong>r<br />

person or with <strong>the</strong> computer program. The Japanese subjects<br />

felt greater confidence in <strong>the</strong>ir self-evaluation <strong>and</strong> were less<br />

interested in seeking fur<strong>the</strong>r in<strong>for</strong>mation when <strong>the</strong>y had unfavorable<br />

self-evaluations than when <strong>the</strong>y had favorable ones. Similarly,<br />

Wada (1988) also reported that Japanese college students<br />

were convinced of <strong>the</strong>ir level of ability on a novel, in<strong>for</strong>mationintegration<br />

task after failure feedback, but not after success<br />

feedback. These data suggest what might be called a modesty<br />

bias or an o<strong>the</strong>r-enhancement bias in social comparison.<br />

A similar modesty bias among those with interdependent<br />

selves has also been suggested by Shikanai (1978), who studied<br />

<strong>the</strong> causal attribution <strong>for</strong> one's own success or failure in an<br />

ability task. Typically, American subjects believe that <strong>the</strong>ir internal<br />

attributes such as ability or competence are extremely<br />

important to <strong>the</strong>ir per<strong>for</strong>mance, <strong>and</strong> this is particularly <strong>the</strong> case<br />

when <strong>the</strong>y have succeeded (e.g., Davis & Stephan, 1980; Gilmor<br />

& Reid, 1979; Greenberg, Pyszczynski, & Solomon, 1982;<br />

Weiner, 1986). In <strong>the</strong> Shikanai study, Japanese college students<br />

per<strong>for</strong>med an anagram task. Half of <strong>the</strong>m were subsequently<br />

led to believe that <strong>the</strong>y scored better than <strong>the</strong> average <strong>and</strong> thus<br />

"succeeded," whereas <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r half were led to believe that <strong>the</strong>y<br />

scored worse than <strong>the</strong> average <strong>and</strong> thus "failed." Subjects were<br />

<strong>the</strong>n asked to choose <strong>the</strong> most important factor in explaining<br />

<strong>the</strong> success or <strong>the</strong> failure <strong>for</strong> each of 10 pairs made from <strong>the</strong> 5<br />

possible causes <strong>for</strong> per<strong>for</strong>mance (i.e., ability, ef<strong>for</strong>t, task difficulty<br />

[or ease], luck, <strong>and</strong> mental-physical "shape" of <strong>the</strong> day).<br />

Shikanai analyzed <strong>the</strong> average number of times each cause was<br />

picked as most important (possible minimum of 0 <strong>and</strong> maximum<br />

of 4). As shown in Figure 5, a modesty bias was again<br />

obtained, especially after success. Whereas failure was attributed<br />

mainly to <strong>the</strong> lack of ef<strong>for</strong>t, success was attributed primar-