Insights - USC Shoah Foundation - University of Southern California

Insights - USC Shoah Foundation - University of Southern California

Insights - USC Shoah Foundation - University of Southern California

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

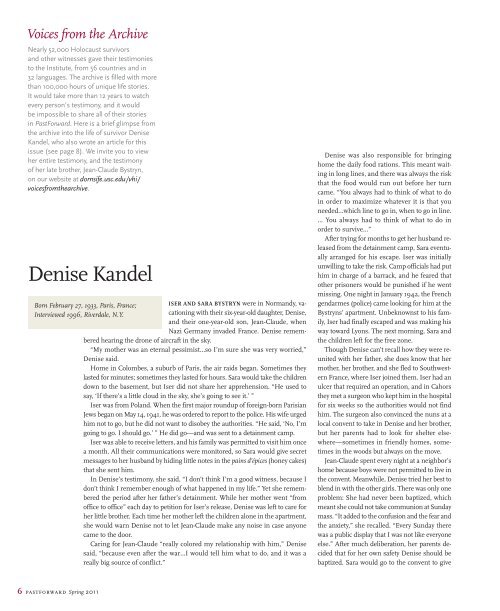

Voices from the Archive<br />

Nearly 52,000 Holocaust survivors<br />

and other witnesses gave their testimonies<br />

to the Institute, from 56 countries and in<br />

32 languages. The archive is filled with more<br />

than 100,000 hours <strong>of</strong> unique life stories.<br />

It would take more than 12 years to watch<br />

every person’s testimony, and it would<br />

be impossible to share all <strong>of</strong> their stories<br />

in PastForward. Here is a brief glimpse from<br />

the archive into the life <strong>of</strong> survivor Denise<br />

Kandel, who also wrote an article for this<br />

issue (see page 8). We invite you to view<br />

her entire testimony, and the testimony<br />

<strong>of</strong> her late brother, Jean-Claude Bystryn,<br />

on our website at dornsife.usc.edu/vhi/<br />

voicesfromthearchive.<br />

Denise Kandel<br />

Born February 27, 1933, Paris, France;<br />

ISER AND SARA BYSTRYN were in Normandy, vacationing<br />

with their six-year-old daughter, Denise,<br />

Interviewed 1996, Riverdale, N.Y.<br />

and their one-year-old son, Jean-Claude, when<br />

Nazi Germany invaded France. Denise remembered<br />

hearing the drone <strong>of</strong> aircraft in the sky.<br />

“My mother was an eternal pessimist…so I’m sure she was very worried,”<br />

Denise said.<br />

Home in Colombes, a suburb <strong>of</strong> Paris, the air raids began. Sometimes they<br />

lasted for minutes; sometimes they lasted for hours. Sara would take the children<br />

down to the basement, but Iser did not share her apprehension. “He used to<br />

say, ‘If there’s a little cloud in the sky, she’s going to see it.’ ”<br />

Iser was from Poland. When the first major roundup <strong>of</strong> foreign-born Parisian<br />

Jews began on May 14, 1941, he was ordered to report to the police. His wife urged<br />

him not to go, but he did not want to disobey the authorities. “He said, ‘No, I’m<br />

going to go. I should go.’ ” He did go—and was sent to a detainment camp.<br />

Iser was able to receive letters, and his family was permitted to visit him once<br />

a month. All their communications were monitored, so Sara would give secret<br />

messages to her husband by hiding little notes in the pains d’épices (honey cakes)<br />

that she sent him.<br />

In Denise’s testimony, she said, “I don’t think I’m a good witness, because I<br />

don’t think I remember enough <strong>of</strong> what happened in my life.” Yet she remembered<br />

the period after her father’s detainment. While her mother went “from<br />

<strong>of</strong>fice to <strong>of</strong>fice” each day to petition for Iser’s release, Denise was left to care for<br />

her little brother. Each time her mother left the children alone in the apartment,<br />

she would warn Denise not to let Jean-Claude make any noise in case anyone<br />

came to the door.<br />

Caring for Jean-Claude “really colored my relationship with him,” Denise<br />

said, “because even after the war…I would tell him what to do, and it was a<br />

really big source <strong>of</strong> conflict.”<br />

Denise was also responsible for bringing<br />

home the daily food rations. This meant waiting<br />

in long lines, and there was always the risk<br />

that the food would run out before her turn<br />

came. “You always had to think <strong>of</strong> what to do<br />

in order to maximize whatever it is that you<br />

needed…which line to go in, when to go in line.<br />

… You always had to think <strong>of</strong> what to do in<br />

order to survive...”<br />

After trying for months to get her husband released<br />

from the detainment camp, Sara eventually<br />

arranged for his escape. Iser was initially<br />

unwilling to take the risk. Camp <strong>of</strong>ficials had put<br />

him in charge <strong>of</strong> a barrack, and he feared that<br />

other prisoners would be punished if he went<br />

missing. One night in January 1942, the French<br />

gendarmes (police) came looking for him at the<br />

Bystryns’ apartment. Unbeknownst to his family,<br />

Iser had finally escaped and was making his<br />

way toward Lyons. The next morning, Sara and<br />

the children left for the free zone.<br />

Though Denise can’t recall how they were reunited<br />

with her father, she does know that her<br />

mother, her brother, and she fled to Southwestern<br />

France, where Iser joined them. Iser had an<br />

ulcer that required an operation, and in Cahors<br />

they met a surgeon who kept him in the hospital<br />

for six weeks so the authorities would not find<br />

him. The surgeon also convinced the nuns at a<br />

local convent to take in Denise and her brother,<br />

but her parents had to look for shelter elsewhere—sometimes<br />

in friendly homes, sometimes<br />

in the woods but always on the move.<br />

Jean-Claude spent every night at a neighbor’s<br />

home because boys were not permitted to live in<br />

the convent. Meanwhile, Denise tried her best to<br />

blend in with the other girls. There was only one<br />

problem: She had never been baptized, which<br />

meant she could not take communion at Sunday<br />

mass. “It added to the confusion and the fear and<br />

the anxiety,” she recalled. “Every Sunday there<br />

was a public display that I was not like everyone<br />

else.” After much deliberation, her parents decided<br />

that for her own safety Denise should be<br />

baptized. Sara would go to the convent to give<br />

6 pastforward Spring 2011