Download - Opera Gallery

Download - Opera Gallery

Download - Opera Gallery

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

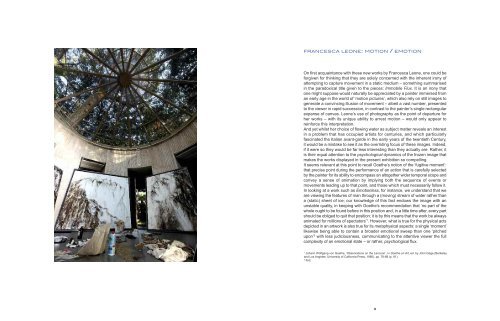

FRANCESCA LEONE: MOTION / EMOTION<br />

On first acquaintance with these new works by Francesca Leone, one could be<br />

forgiven for thinking that they are solely concerned with the inherent irony of<br />

attempting to capture movement in a static medium – something summarised<br />

in the paradoxical title given to the pieces: Immobile Flux. It is an irony that<br />

one might suppose would naturally be appreciated by a painter immersed from<br />

an early age in the world of ‘motion pictures’, which also rely on still images to<br />

generate a convincing illusion of movement – albeit a vast number, presented<br />

to the viewer in rapid succession, in contrast to the painter’s single rectangular<br />

expanse of canvas. Leone’s use of photography as the point of departure for<br />

her works – with its unique ability to arrest motion – would only appear to<br />

reinforce this interpretation.<br />

And yet whilst her choice of flowing water as subject matter reveals an interest<br />

in a problem that has occupied artists for centuries, and which particularly<br />

fascinated the Italian avant-garde in the early years of the twentieth Century,<br />

it would be a mistake to see it as the overriding focus of these images. Indeed,<br />

if it were so they would be far less interesting than they actually are. Rather, it<br />

is their equal attention to the psychological dynamics of the frozen image that<br />

makes the works displayed in the present exhibition so compelling.<br />

It seems relevant at this point to recall Goethe’s notion of the ‘fugitive moment’:<br />

that precise point during the performance of an action that is carefully selected<br />

by the painter for its ability to encompass an altogether wider temporal scope and<br />

convey a sense of animation by implying both the sequence of events or<br />

movements leading up to that point, and those which must necessarily follow it.<br />

In looking at a work such as Emotionless, for instance, we understand that we<br />

are viewing the features of man through a (moving) stream of water rather than<br />

a (static) sheet of ice; our knowledge of this fact endows the image with an<br />

unstable quality, in keeping with Goethe’s recommendation that ‘no part of the<br />

whole ought to be found before in this position and, in a little time after, every part<br />

should be obliged to quit that position; it is by this means that the work be always<br />

animated for millions of spectators’ 1 . However, what is true for the physical acts<br />

depicted in an artwork is also true for its metaphysical aspects: a single ‘moment’<br />

likewise being able to contain a broader emotional sweep than one ‘pitched<br />

upon’ 2 with less judiciousness, communicating to the attentive viewer the full<br />

complexity of an emotional state – or rather, psychological flux.<br />

1<br />

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, ‘Observations on the Laocoon’, in Goethe on Art, ed. by John Gage (Berkeley<br />

and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1980), pp. 78-88 (p. 81).<br />

2<br />

Ibid.<br />

9