F&N Bulletin Vol 23 No 1b - United Nations University

F&N Bulletin Vol 23 No 1b - United Nations University

F&N Bulletin Vol 23 No 1b - United Nations University

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

28<br />

tion in public schools, at the same time as nutrition<br />

education and physical activity programs to prevent<br />

increasing obesity in private schools are apparently<br />

called for.<br />

The study also showed a decreasing Z score in<br />

height-for-age and weight-for-age with age from 8<br />

to 10 years in both public and private schools. This<br />

trend was also reflected in the increasing prevalence<br />

of stunting and underweight with age from 8 to 10<br />

years, particularly in public schools. If this trend is real,<br />

it may have important programmatic implications.<br />

However, it may reflect, at least in part, the start of<br />

puberty and the influence of ethnicity affecting the<br />

significance of the differences from NCHS standards.<br />

As Flegal [9] pointed out, no valid comparisons in<br />

prevalence among age and sex groups may be made<br />

using statistical approaches in defining nutritional<br />

status, because variability among these groups may<br />

be constrained by the assumptions built into the<br />

cutoffs used. Thus, in contrast to public schoolchildren<br />

where thinness (BMI less than the 5th percentile)<br />

increased with age, thinness generally decreased with<br />

age among private schoolchildren. There is a need<br />

either to examine the reference standards for use in<br />

Filipino preadolescent and adolescent children or to<br />

validate the cutoff points used.<br />

Private schoolchildren had a greater relative change<br />

in height and weight Z scores from 8 to 10 years of<br />

age than public schoolchildren, resulting in a larger<br />

increase in BMI with age. The increase in BMI with<br />

age has also been noted among American children<br />

[8]. However, the increase should be interpreted with<br />

caution because of limitations of BMI as a measure<br />

of nutritional status in older schoolchildren due to<br />

changing body composition and degree of maturity<br />

with age and the influence of ethnicity.<br />

There was an increasing prevalence of underweight<br />

and stunting with age from 8 to 10 years, but a generally<br />

decreasing prevalence of overweight, in spite of<br />

the generally increasing BMI. However, further study<br />

is needed to determine whether these trends and differences<br />

are real and not due to reference standards<br />

and cutoff points.<br />

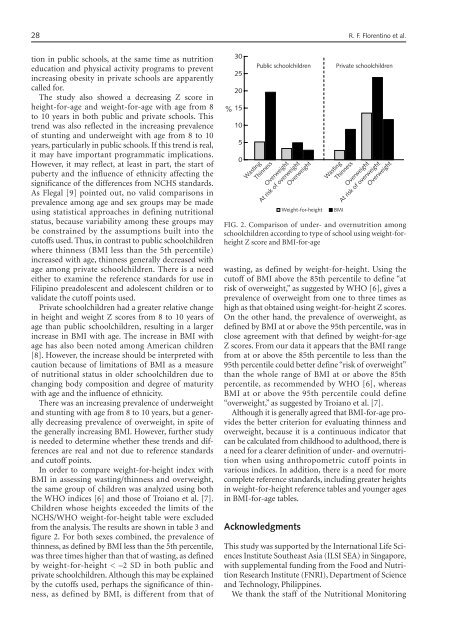

In order to compare weight-for-height index with<br />

BMI in assessing wasting/thinness and overweight,<br />

the same group of children was analyzed using both<br />

the WHO indices [6] and those of Troiano et al. [7].<br />

Children whose heights exceeded the limits of the<br />

NCHS/WHO weight-for-height table were excluded<br />

from the analysis. The results are shown in table 3 and<br />

figure 2. For both sexes combined, the prevalence of<br />

thinness, as defined by BMI less than the 5th percentile,<br />

was three times higher than that of wasting, as defined<br />

by weight-for-height < –2 SD in both public and<br />

private schoolchildren. Although this may be explained<br />

by the cutoffs used, perhaps the significance of thinness,<br />

as defined by BMI, is different from that of<br />

30<br />

25<br />

20<br />

% 15<br />

10<br />

5<br />

0<br />

Public schoolchildren<br />

Wasting<br />

Thinness<br />

Overweight<br />

At risk of overweight<br />

Overweight<br />

FIG. 2. Comparison of under- and overnutrition among<br />

schoolchildren according to type of school using weight-forheight<br />

Z score and BMI-for-age<br />

wasting, as defined by weight-for-height. Using the<br />

cutoff of BMI above the 85th percentile to define “at<br />

risk of overweight,” as suggested by WHO [6], gives a<br />

prevalence of overweight from one to three times as<br />

high as that obtained using weight-for-height Z scores.<br />

On the other hand, the prevalence of overweight, as<br />

defined by BMI at or above the 95th percentile, was in<br />

close agreement with that defined by weight-for-age<br />

Z scores. From our data it appears that the BMI range<br />

from at or above the 85th percentile to less than the<br />

95th percentile could better define “risk of overweight”<br />

than the whole range of BMI at or above the 85th<br />

percentile, as recommended by WHO [6], whereas<br />

BMI at or above the 95th percentile could define<br />

“overweight,” as suggested by Troiano et al. [7].<br />

Although it is generally agreed that BMI-for-age provides<br />

the better criterion for evaluating thinness and<br />

overweight, because it is a continuous indicator that<br />

can be calculated from childhood to adulthood, there is<br />

a need for a clearer definition of under- and overnutrition<br />

when using anthropometric cutoff points in<br />

various indices. In addition, there is a need for more<br />

complete reference standards, including greater heights<br />

in weight-for-height reference tables and younger ages<br />

in BMI-for-age tables.<br />

Acknowledgments<br />

Weight-for-height<br />

Private schoolchildren<br />

Wasting<br />

Thinness<br />

Overweight<br />

At risk of overweight<br />

Overweight<br />

This study was supported by the International Life Sciences<br />

Institute Southeast Asia (ILSI SEA) in Singapore,<br />

with supplemental funding from the Food and Nutrition<br />

Research Institute (FNRI), Department of Science<br />

and Technology, Philippines.<br />

We thank the staff of the Nutritional Monitoring<br />

BMI<br />

R. F. Florentino et al.