The origins of nominal affixes in Austroasiatic and ... - Roger Blench

The origins of nominal affixes in Austroasiatic and ... - Roger Blench

The origins of nominal affixes in Austroasiatic and ... - Roger Blench

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Nom<strong>in</strong>al <strong>affixes</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Austroasiatic</strong> <strong>and</strong> S<strong>in</strong>o-Tibetan <strong>Roger</strong> <strong>Blench</strong> Circulation draft<br />

<strong>The</strong>re is strong evidence for borrow<strong>in</strong>g between phyla; for example, one <strong>of</strong> the ‘animal’ classifiers <strong>in</strong><br />

<strong>Austroasiatic</strong> is probably a borrow<strong>in</strong>g from Daic. Classifiers <strong>of</strong>ten have a transparent etymological orig<strong>in</strong>,<br />

typically grammaticalised body parts (see e.g. Becker 1975 for Burmese), <strong>and</strong> this process <strong>of</strong><br />

grammaticalisation has been similarly documented for noun-class <strong>affixes</strong> <strong>in</strong> African languages.<br />

Both <strong>Austroasiatic</strong> <strong>and</strong> S<strong>in</strong>o-Tibetan may orig<strong>in</strong>ally have had simple stems, with no <strong>affixes</strong> mark<strong>in</strong>g number,<br />

case, semantics or gender. Nom<strong>in</strong>al classifiers, usually CV(C) syllables with semantic assignations, <strong>and</strong><br />

were put together with nouns, usually preced<strong>in</strong>g them, as is still very much the situation <strong>in</strong> Daic languages.<br />

It is possible that S<strong>in</strong>o-Tibetan <strong>and</strong> <strong>Austroasiatic</strong> <strong>nom<strong>in</strong>al</strong> classifiers became bound to the root <strong>and</strong> reduced<br />

to C with an epenthetic vowel follow<strong>in</strong>g, hence the transformation <strong>in</strong>to <strong>affixes</strong>. Although this occurred to a<br />

greater or lesser extent <strong>in</strong> different languages, consciousness <strong>of</strong> their separateness was reta<strong>in</strong>ed. As a<br />

consequence, they can be shifted to the end <strong>of</strong> the root, deleted <strong>in</strong> some languages <strong>and</strong> a new prefix added,<br />

elsewhere a new prefix was added <strong>in</strong> front <strong>of</strong> the exist<strong>in</strong>g prefix. Meanwhile, dist<strong>in</strong>ct <strong>nom<strong>in</strong>al</strong> classifiers<br />

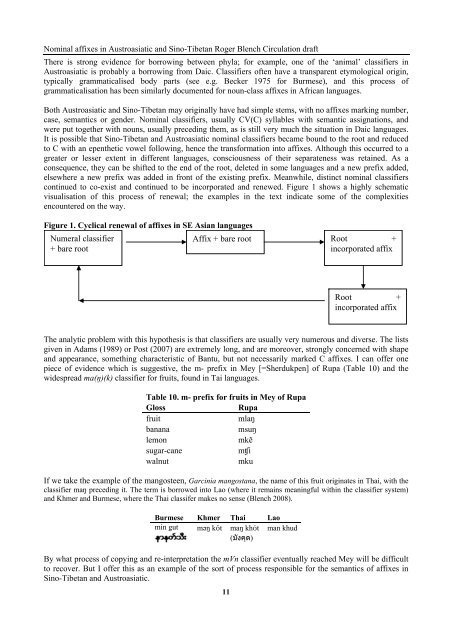

cont<strong>in</strong>ued to co-exist <strong>and</strong> cont<strong>in</strong>ued to be <strong>in</strong>corporated <strong>and</strong> renewed. Figure 1 shows a highly schematic<br />

visualisation <strong>of</strong> this process <strong>of</strong> renewal; the examples <strong>in</strong> the text <strong>in</strong>dicate some <strong>of</strong> the complexities<br />

encountered on the way.<br />

Figure 1. Cyclical renewal <strong>of</strong> <strong>affixes</strong> <strong>in</strong> SE Asian languages<br />

Numeral classifier<br />

+ bare root<br />

Affix + bare root Root +<br />

<strong>in</strong>corporated affix<br />

Root +<br />

<strong>in</strong>corporated affix<br />

<strong>The</strong> analytic problem with this hypothesis is that classifiers are usually very numerous <strong>and</strong> diverse. <strong>The</strong> lists<br />

given <strong>in</strong> Adams (1989) or Post (2007) are extremely long, <strong>and</strong> are moreover, strongly concerned with shape<br />

<strong>and</strong> appearance, someth<strong>in</strong>g characteristic <strong>of</strong> Bantu, but not necessarily marked C <strong>affixes</strong>. I can <strong>of</strong>fer one<br />

piece <strong>of</strong> evidence which is suggestive, the m- prefix <strong>in</strong> Mey [=Sherdukpen] <strong>of</strong> Rupa (Table 10) <strong>and</strong> the<br />

widespread ma(ŋ)(k) classifier for fruits, found <strong>in</strong> Tai languages.<br />

Table 10. m- prefix for fruits <strong>in</strong> Mey <strong>of</strong> Rupa<br />

Gloss<br />

Rupa<br />

fruit<br />

mlaŋ<br />

banana<br />

msuŋ<br />

lemon<br />

mkẽ<br />

sugar-cane<br />

mʧi<br />

walnut<br />

mku<br />

If we take the example <strong>of</strong> the mangosteen, Garc<strong>in</strong>ia mangostana, the name <strong>of</strong> this fruit orig<strong>in</strong>ates <strong>in</strong> Thai, with the<br />

classifier maŋ preced<strong>in</strong>g it. <strong>The</strong> term is borrowed <strong>in</strong>to Lao (where it rema<strong>in</strong>s mean<strong>in</strong>gful with<strong>in</strong> the classifier system)<br />

<strong>and</strong> Khmer <strong>and</strong> Burmese, where the Thai classifer makes no sense (<strong>Blench</strong> 2008).<br />

Burmese Khmer Thai Lao<br />

m<strong>in</strong> gut məŋ kʊ̌ t maŋ khʊ́ t man khud<br />

(มังคุด)<br />

By what process <strong>of</strong> copy<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> re-<strong>in</strong>terpretation the mVn classifier eventually reached Mey will be difficult<br />

to recover. But I <strong>of</strong>fer this as an example <strong>of</strong> the sort <strong>of</strong> process responsible for the semantics <strong>of</strong> <strong>affixes</strong> <strong>in</strong><br />

S<strong>in</strong>o-Tibetan <strong>and</strong> <strong>Austroasiatic</strong>.<br />

11