Deliverance to the - Charles Bethea

Deliverance to the - Charles Bethea

Deliverance to the - Charles Bethea

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

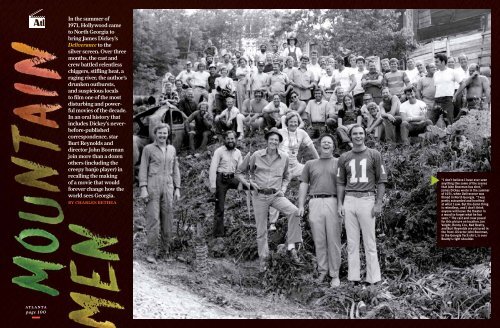

In <strong>the</strong> summer of<br />

1971, Hollywood came<br />

<strong>to</strong> North Georgia <strong>to</strong><br />

bring James Dickey’s<br />

<strong>Deliverance</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

silver screen. Over three<br />

months, <strong>the</strong> cast and<br />

crew battled relentless<br />

chiggers, stifling heat, a<br />

raging river, <strong>the</strong> author’s<br />

drunken outbursts,<br />

and suspicious locals<br />

<strong>to</strong> film one of <strong>the</strong> most<br />

disturbing and powerful<br />

movies of <strong>the</strong> decade.<br />

In an oral his<strong>to</strong>ry that<br />

includes Dickey’s neverbefore-published<br />

correspondence, star<br />

Burt Reynolds and<br />

direc<strong>to</strong>r John Boorman<br />

join more than a dozen<br />

o<strong>the</strong>rs (including <strong>the</strong><br />

creepy banjo player) in<br />

recalling <strong>the</strong> making<br />

of a movie that would<br />

forever change how <strong>the</strong><br />

world sees Georgia.<br />

by charles be<strong>the</strong>a<br />

“I don’t believe I have ever seen<br />

anything like some of <strong>the</strong> scenes<br />

that John Boorman has shot,”<br />

James Dickey wrote in <strong>the</strong> summer<br />

of 1971, when <strong>Deliverance</strong> was<br />

filmed in North Georgia. “I was<br />

pretty as<strong>to</strong>unded and horrified<br />

at what I saw. But <strong>the</strong> damn thing<br />

is relentless, and I don’t think<br />

anyone will leave <strong>the</strong> <strong>the</strong>ater in<br />

a mood <strong>to</strong> forget what he has<br />

seen.” The cast and crew posed<br />

for this picture on location. Jon<br />

Voight, Ronny Cox, Ned Beatty,<br />

and Burt Reynolds are pictured in<br />

<strong>the</strong> front. Direc<strong>to</strong>r John Boorman,<br />

in <strong>the</strong> Georgia Tech shirt, is over<br />

Beatty’s right shoulder.<br />

atlanta<br />

page 100

It’s near<br />

impossible<br />

<strong>to</strong> float down<br />

a river in Georgia<br />

without<br />

someone<br />

referencing<br />

<strong>Deliverance</strong>,<br />

usually exclaiming, in an exaggerated drawl, “Squeal like a pig!”<br />

That many of <strong>the</strong>se giddy rivergoers—almost always from <strong>the</strong> Big<br />

City—have never seen <strong>the</strong> film or read James Dickey’s 1970 novel,<br />

much less considered <strong>the</strong> horrific act that line conjures, is <strong>the</strong><br />

point: Movie lines live a life of <strong>the</strong>ir own. Just visit squeallikeapig.<br />

com, <strong>the</strong> personal website of ac<strong>to</strong>r Bill McKinney, who uttered it.<br />

Or spend a few minutes on a summer Sunday watching <strong>the</strong> rafts<br />

plunge down Bull Sluice, <strong>the</strong> Chat<strong>to</strong>oga River’s main event, and<br />

listen for <strong>the</strong> jokes straining over <strong>the</strong> roar of <strong>the</strong> rapids. Is it <strong>the</strong><br />

river that made <strong>the</strong> film, or <strong>the</strong> film that made <strong>the</strong> river? James<br />

Dickey wrote a dark, muscular novel, which became an even<br />

darker, more unsettling film. It’s about a canoe trip gone wrong on<br />

a remote river in North Georgia, but it’s also about “<strong>the</strong> measures<br />

that decent people may—or must—take against <strong>the</strong> amoral human<br />

monsters that are constantly amongst us, whe<strong>the</strong>r in <strong>the</strong> woods<br />

of North Georgia or on <strong>the</strong> streets of New York,” as Dickey wrote<br />

<strong>to</strong> William F. Buckley in September of 1972. When I first read <strong>the</strong><br />

book, at seventeen, it felt like a portal <strong>to</strong> manhood. <strong>Deliverance</strong> is<br />

a product of <strong>the</strong> male ego: <strong>the</strong> egos of <strong>the</strong> alcoholic-poet-turnednovelist<br />

(when <strong>the</strong> film was being made, Dickey wrote in a journal,<br />

“It seems <strong>to</strong> me that I am <strong>the</strong> bearer of some kind of immortal<br />

message <strong>to</strong> humankind”), a fearless English direc<strong>to</strong>r, and, not<br />

least of all, a B-movie ac<strong>to</strong>r who grew up in Waycross, Georgia,<br />

whose name was Bur<strong>to</strong>n Leon Reynolds Jr. And <strong>the</strong>n, still, <strong>the</strong><br />

fictional egos of <strong>the</strong> four men in <strong>the</strong> two canoes who, led by <strong>the</strong><br />

possessed Lewis, go down <strong>the</strong> fictional Cahulawassee “because<br />

it’s <strong>the</strong>re.” There for now, that is. It’s a disappearing river, about <strong>to</strong><br />

be dammed <strong>to</strong> generate power for <strong>the</strong> civilized folks from Atlanta.<br />

Instead of Roman Polanski or Sam<br />

Peckinpah, who were both discussed,<br />

Warner Bro<strong>the</strong>rs chose <strong>the</strong> lesser-known<br />

John Boorman <strong>to</strong> direct. He was a direc<strong>to</strong>r<br />

on <strong>the</strong> rise, having done Point Blank and<br />

Hell in <strong>the</strong> Pacific—both starring Lee Marvin—in<br />

<strong>the</strong> previous four years. Warren<br />

Beatty, Robert Redford, Charl<strong>to</strong>n Hes<strong>to</strong>n,<br />

Paul Newman, Jack Nicholson, Marlon<br />

Brando, Gene Hackman, and George C.<br />

Scott were all considered for parts that<br />

went <strong>to</strong> newcomers Jon Voight and Burt<br />

Reynolds. Nearly half <strong>the</strong> cast were local<br />

mountain people. It is something of a miracle,<br />

you begin <strong>to</strong> realize, that this bunch<br />

made a Hollywood film on a wild river that<br />

almost no one had canoed, in a state where<br />

movies weren’t made, and that it became<br />

one of <strong>the</strong> most lasting depictions—<strong>to</strong> say<br />

nothing of its accuracy—of <strong>the</strong> rural South,<br />

and North Georgia in particular.<br />

It also set in motion four decades of<br />

film production in Georgia. Reynolds ultimately<br />

appeared in eight films made in <strong>the</strong><br />

state (see page 87). For fiscal year 2011, <strong>the</strong><br />

impact of <strong>the</strong> film industry in Georgia was<br />

$2.4 billion. How did this start? To compile<br />

this oral his<strong>to</strong>ry of Georgia’s cinematic big<br />

bang, Atlanta magazine interviewed more<br />

than twenty people who helped bring<br />

<strong>Deliverance</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> big screen, and quoted<br />

from some of <strong>the</strong> memoirs and letters associated<br />

with <strong>the</strong> production.<br />

///////////////////////////<br />

james dickey was born at Crawford<br />

Long hospital on February 2, 1923. Though<br />

he wanted <strong>to</strong> be a fighter pilot—and later<br />

said he was—Dickey was a flight naviga<strong>to</strong>r<br />

and weapons officer in World War II.<br />

He became an advertising executive and<br />

celebrated poet before publishing his first<br />

novel, <strong>Deliverance</strong>, in 1970. In Summer of<br />

<strong>Deliverance</strong>: A Memoir of Fa<strong>the</strong>r and Son,<br />

Dickey’s oldest son, Chris<strong>to</strong>pher, described<br />

his fa<strong>the</strong>r as “<strong>the</strong> advertising man by day,<br />

<strong>the</strong> poet by night, <strong>the</strong> archer and canoer<br />

and tennis player on <strong>the</strong> weekends. He was<br />

<strong>the</strong> fa<strong>the</strong>r in <strong>the</strong> armchair on Westminster<br />

Excerpts from James Dickey’s letters and pho<strong>to</strong>graphs<br />

reprinted with permission from <strong>the</strong> Estate<br />

of James Dickey and <strong>the</strong> Manuscript, Archives,<br />

and Rare Book Library, Emory University.<br />

Above, left: James Dickey, who played <strong>the</strong> sheriff, and his son Chris<strong>to</strong>pher. Above, right:<br />

Burt Reynolds. Below: Billy Redden was just a teenager when he was cast as <strong>the</strong> banjo player,<br />

even though he didn’t play <strong>the</strong> instrument. He still doesn’t. Pho<strong>to</strong>graphed in Clay<strong>to</strong>n on July 30.<br />

1 0 2 | at l a n ta | s e p t e m b e r 2 0 1 1<br />

r e d d e n : p h o t o g r a p h b y j a s o n m a r i s

Above, Jon Voight’s climactic climb up <strong>the</strong> gorge had <strong>the</strong> cast and crew on<br />

edge. Below, James Dickey and John Boorman. Right, <strong>the</strong> harrowing rape scene<br />

required makeup <strong>to</strong> show an attacker impaled with an arrow.<br />

Jon [Voight]<br />

was in a very<br />

depressed state.<br />

He wanted <strong>to</strong><br />

give up acting.<br />

He says that<br />

I saved his life<br />

and <strong>the</strong>n spent<br />

<strong>the</strong> whole<br />

film trying <strong>to</strong><br />

kill him.<br />

—John Boorman<br />

[Circle], <strong>the</strong> half-rebellious son at Sunday<br />

dinners on West Wesley. He was lifting<br />

weights, still, in <strong>the</strong> carport, and cruising<br />

<strong>the</strong> Buckhead strip malls in <strong>the</strong> MGA<br />

sports car his mo<strong>the</strong>r bought him . . . He<br />

wanted <strong>to</strong> try everything.”<br />

lewis king, eighty-three, was a friend<br />

of James Dickey’s and a technical adviser for<br />

<strong>the</strong> film. He lives in Sautee-Nacoochee. Dickey<br />

dedicated <strong>the</strong> book <strong>to</strong> me because I <strong>to</strong>ok<br />

him canoeing. He enjoyed it, but he wasn’t<br />

much of a paddler.<br />

doug woodward, seventy-four, was a<br />

cofounder of Sou<strong>the</strong>astern Expeditions guiding<br />

service and a technical adviser for <strong>the</strong> film.<br />

He lives in Franklin, North Carolina. From his<br />

memoir, Wherever Waters Flow: Dickey<br />

was an imposing figure of a man, and his<br />

presence filled <strong>the</strong> room. But it was much<br />

more than physical. There was a mystique<br />

about him—of things hidden, perhaps ominous—that<br />

he enjoyed perpetuating. There<br />

were references <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> canoe trip which he<br />

and King had taken years before . . . Dickey<br />

would not describe details of that canoe<br />

trip. With a knowing smile, he would<br />

simply say, “There’s a lot more truth in <strong>the</strong><br />

s<strong>to</strong>ry [<strong>Deliverance</strong>] than you might think.”<br />

king I had <strong>to</strong> go far<strong>the</strong>r down <strong>the</strong> river<br />

<strong>to</strong> wait. I met a young guy and his fa<strong>the</strong>r.<br />

The fa<strong>the</strong>r said, “Stay with him, boy.” I<br />

think he probably had a still down <strong>the</strong>re.<br />

We waited. The man thought I shouldn’t<br />

have been snooping around with a bunch<br />

of maps. I think Jim used that.<br />

burt reynolds, seventy-five, played<br />

Lewis Medlock in <strong>the</strong> film. He now lives in<br />

Jupiter, Florida. Dickey and I didn’t see<br />

eye <strong>to</strong> eye on a lot of things, but I did love<br />

<strong>the</strong> book. He said, “You know, it really<br />

happened. We didn’t get <strong>the</strong>re in time <strong>to</strong><br />

kill <strong>the</strong> guy.” I didn’t ask him fur<strong>the</strong>r. Do<br />

I think it’s true? I don’t know. Dickey was<br />

one of <strong>the</strong> great s<strong>to</strong>rytellers ever. And I<br />

don’t mean liars.<br />

chris dickey, sixty, was a stand-in.<br />

He lives in Paris, where he is <strong>the</strong> Paris bureau<br />

chief and Middle East regional edi<strong>to</strong>r for<br />

Newsweek. From Summer of <strong>Deliverance</strong>:<br />

<strong>Deliverance</strong> was just one of his projects,<br />

something <strong>to</strong> talk through on our long<br />

drives across two continents. And as I read<br />

it that night after my marriage, in a motel<br />

on <strong>the</strong> New Jersey Turnpike, I had <strong>to</strong> admit<br />

it was very damn good. Much as I wanted<br />

<strong>to</strong>, I couldn’t put it down.<br />

Dickey wrote a screenplay, which was heavily<br />

revised by direc<strong>to</strong>r John Boorman. The revisions<br />

would be <strong>the</strong> subject of much acrimony.<br />

james dickey Letter <strong>to</strong> Eric Wallace,<br />

April 27, 1971: I first did a long “treatment”<br />

very heavily influenced by James<br />

Agee, and I thought it was very good, but it<br />

turned out <strong>to</strong> run about seven hours.<br />

woodward From Wherever Waters<br />

Flow: In King’s living room, [Dickey]<br />

held a copy in his hand. He turned <strong>to</strong> me,<br />

motioning with <strong>the</strong> script, and asked, “It’s<br />

a good book, don’t you think? Do you really<br />

like it?” . . . As he <strong>to</strong>ssed down more alcohol<br />

and <strong>the</strong> evening wore on, <strong>the</strong> question was<br />

repeated, until it became embarrassing.<br />

james dickey Letter <strong>to</strong> Edwin Peeples,<br />

January 1, 1971: I have a good direc<strong>to</strong>r,<br />

though an Englishman, John Boorman. I<br />

<strong>to</strong>ok him over in<strong>to</strong> North Georgia about six<br />

weeks ago, looking for locations, and damn<br />

near got him bit by a big copperhead. Now<br />

that would have been a <strong>to</strong>uch of “au<strong>the</strong>nticity.”<br />

Imagine having an Englishman filming<br />

a novel about North Georgia in North<br />

Georgia, his veins full of North Georgia<br />

copperhead poison.<br />

We have a good script, which I did,<br />

which John redid, and which I redid his<br />

redoing of. Anyway, we feel that we can<br />

legitimately claim equal credit, and that we<br />

have something which satisfies us both,<br />

which I guess is <strong>the</strong> point anyway.<br />

john boorman, seventy-eight, lives<br />

near Dublin, Ireland. He had a great sense<br />

of fantasy. When I first talked <strong>to</strong> him about<br />

<strong>the</strong> film, he said, “I’m going <strong>to</strong> tell you<br />

something that I’ve never <strong>to</strong>ld a living soul:<br />

Everything in that book happened <strong>to</strong> me.”<br />

He <strong>to</strong>ld everyone else <strong>the</strong> same thing. Of<br />

course, nothing in that book actually happened<br />

<strong>to</strong> him. Continued on page 118<br />

s e p t e m b e r 2 0 1 1 | at l a n ta | 1 0 5

Mountain Men<br />

Continued from page 105<br />

sarah rickman, eighty-five, was married<br />

<strong>to</strong> Frank Rickman, now deceased, who built<br />

sets and found filming locations in North Georgia.<br />

She lives in Clay<strong>to</strong>n. John Boorman had<br />

pink knitting thread holding his glasses. He<br />

was English and his wife was German.<br />

boorman I was pretty hot at <strong>the</strong> time. I<br />

read <strong>the</strong> manuscript and knew exactly how<br />

<strong>to</strong> do it. Burt and Jon were both not very hot<br />

at <strong>the</strong> time. Burt had done three TV series,<br />

which had all failed. Living in Ireland, I<br />

didn’t realize that.<br />

Voight had been in Midnight Cowboy, but<br />

little else of note. Reynolds had been in movies<br />

that, by his own account, “made you run out of<br />

<strong>the</strong> <strong>the</strong>ater screaming if you saw <strong>the</strong>m twice.”<br />

These included Caine and Skullduggery.<br />

Voight and Reynolds were joined by two Shakespearean<br />

ac<strong>to</strong>rs who’d never done movies: Ned<br />

Beatty and Ronny Cox. The film’s budget was<br />

$1.8 million.<br />

chris dickey Burt wanted respect. He<br />

wasn’t coming from <strong>the</strong> stage, or from an<br />

Academy Award–winning film. He was a<br />

former stuntman, and he wanted <strong>to</strong> be a star.<br />

reynolds I was crazy and young and<br />

thought I was <strong>to</strong>tally indomitable. <strong>Deliverance</strong><br />

saved me in terms of being thought of<br />

as a serious ac<strong>to</strong>r.<br />

ed spivia, seventy, was <strong>the</strong> state’s first<br />

film commissioner and is now chairman of <strong>the</strong><br />

Georgia Film, Video, and Music Advisory Commission.<br />

He lives on Lake Lanier. Dickey kept<br />

slapping Burt on <strong>the</strong> back and calling him<br />

Lewis. I think Burt punched him out.<br />

reynolds He was about six foot seven,<br />

240. He didn’t want <strong>to</strong> get physical with me.<br />

He was big, but I was crazy. After fighting<br />

<strong>the</strong> river, Dickey would have been a cinch.<br />

The Chat<strong>to</strong>oga was a dangerous, largely<br />

unknown river forty years ago. And <strong>the</strong> men<br />

expected <strong>to</strong> paddle down it were novices in<br />

canoes.<br />

boorman It was a location film, and<br />

I chose <strong>the</strong> river. It was <strong>the</strong> most suitable<br />

place <strong>to</strong> shoot, so we did it <strong>the</strong>re. I’ve filmed<br />

in more remote places, like <strong>the</strong> Amazon.<br />

reynolds I hadn’t paddled a river until<br />

we did <strong>the</strong> movie. None of us had. At that<br />

time, no one had done <strong>the</strong> Chat<strong>to</strong>oga in a<br />

canoe. Just rafts that crashed and burned.<br />

buzz williams, sixty-one, was an early<br />

paddler of <strong>the</strong> Chat<strong>to</strong>oga. Now <strong>the</strong> executive<br />

direc<strong>to</strong>r of <strong>the</strong> Chat<strong>to</strong>oga Conservancy, he lives<br />

in Long Creek, South Carolina. In 1968 I was<br />

a high school senior in Pendle<strong>to</strong>n, South<br />

Carolina. A couple fellas were transferred<br />

<strong>to</strong> a mill down here, and <strong>the</strong>y had kayaks.<br />

Nobody here knew what a kayak was. They<br />

found this great river and asked me <strong>to</strong> go<br />

with <strong>the</strong>m. It was <strong>the</strong> Chat<strong>to</strong>oga.<br />

reynolds The first day <strong>the</strong> four of us<br />

went out, I had Ned Beatty in <strong>the</strong> front of<br />

my boat—which was not a good idea—and<br />

Jon had Ronny in <strong>the</strong> front of his boat and<br />

we were in this little pond and <strong>the</strong> boats<br />

tipped over. I remember two old paddlers<br />

sitting on <strong>the</strong> beach saying, “This is going<br />

<strong>to</strong> be a long summer.”<br />

claude terry, seventy-four, was a<br />

technical adviser and body double for Jon<br />

Voight. He cofounded American Rivers and<br />

Sou<strong>the</strong>astern Expeditions guiding service. He<br />

lives in Atlanta. They had me up for a day<br />

<strong>to</strong> teach canoeing, and Burt wouldn’t come.<br />

They had Fred Bear teach archery, and Burt<br />

wouldn’t do that ei<strong>the</strong>r.<br />

williams You could get seriously lost,<br />

or killed. It was one of <strong>the</strong> few remaining<br />

wild places in <strong>the</strong> sou<strong>the</strong>rn Appalachians.<br />

james dickey Letter <strong>to</strong> Larry DuBois,<br />

April 8, 1971: This is going <strong>to</strong> be some thing,<br />

and some movie. If we just don’t get everybody’s<br />

brains knocked out on those rocks!<br />

They are pure murder, I can tell you.<br />

woodward From Wherever Waters<br />

Flow: We might be called on for technical<br />

advice, such as, “Where can we find a rock<br />

face with a swift current running past,<br />

that Jon Voight can be clawing at for a<br />

finger hold—and where we don’t lose him<br />

down river!” Thus <strong>the</strong> naming of “<strong>Deliverance</strong><br />

Rock.”<br />

kyle weisbrod, thirty-two, guided<br />

Sou<strong>the</strong>astern Expeditions raft trips in 2000 and<br />

2001. He lives in Seattle. Most of <strong>the</strong> Chat<strong>to</strong>oga<br />

shots were from <strong>Deliverance</strong> Rock<br />

and Screaming Left Hand Turn. They use<br />

Screaming Left Hand Turn three or four<br />

times. They didn’t <strong>to</strong>uch Bull Sluice.<br />

The set was a diverse place, as many of <strong>the</strong><br />

smaller roles were filled by mountain people in<br />

North Georgia.<br />

betsy fowler, seventy-six, was married<br />

<strong>to</strong> John Fowler, now deceased; in <strong>the</strong> film,<br />

he played a doc<strong>to</strong>r who tends <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> injured<br />

canoers. She has lived in Rabun County for <strong>the</strong><br />

past forty-eight years. Boorman <strong>to</strong>ld Frank<br />

Rickman <strong>to</strong> go out and find all <strong>the</strong> people in<br />

Rabun County who were challenged in any<br />

way—physically and mentally.<br />

boorman Frank was a bulldozer man.<br />

spivia Frank knew those mountains and<br />

rivers better than anybody. His fa<strong>the</strong>r was<br />

sheriff of Rabun County and used him as a<br />

catch dog for moonshiners. Frank found <strong>the</strong><br />

buck dancer at <strong>the</strong> gas station. And he’s <strong>the</strong><br />

one that put <strong>the</strong> pig-squealing in it. Governor<br />

Carter ended up appointing him <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

film commission.<br />

rickman They wanted a snake <strong>to</strong> swim<br />

through <strong>the</strong> river and hold its head up.<br />

Frank knew exactly which snake <strong>to</strong> get.<br />

Frank didn’t go <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> movies, but he liked<br />

making <strong>the</strong>m.<br />

spivia He was a red-clay Michelangelo.<br />

Billy Redden, fifteen years old at <strong>the</strong> time,<br />

played Lonnie, <strong>the</strong> creepy boy in <strong>the</strong> dueling<br />

banjos scene.<br />

billy redden, fifty-six, lives in Dillard,<br />

Georgia, and works at Walmart. A couple<br />

casting direc<strong>to</strong>rs came in<strong>to</strong> our school and<br />

<strong>the</strong>y picked me out. They just said, “Sit<br />

<strong>the</strong>re and be natural.” There was ano<strong>the</strong>r<br />

local boy behind me, Mike Atlas, playing <strong>the</strong><br />

banjo. I just had two scenes: sitting on <strong>the</strong><br />

porch, <strong>the</strong>n <strong>the</strong> bridge. The rest of <strong>the</strong> movie<br />

I don’t know nothing about. I left.<br />

boorman [Redden] didn’t play <strong>the</strong><br />

banjo, you know. That was ano<strong>the</strong>r boy,<br />

reaching through his sleeve. We didn’t put<br />

him in <strong>the</strong> credits.<br />

The set attracted a lot of attention; much of it<br />

came from Reynolds’s harem of women, but<br />

<strong>the</strong>re were also <strong>to</strong>urism officials interested in<br />

promoting <strong>the</strong> state.<br />

spivia I was edi<strong>to</strong>r of a little state publication<br />

called Georgia Progress. I went up <strong>to</strong><br />

Clay<strong>to</strong>n <strong>to</strong> see what <strong>the</strong>y were doing with<br />

<strong>Deliverance</strong>. I nosed around and found out<br />

<strong>the</strong>y were buying property along <strong>the</strong> river,<br />

and hotels, and food. Helping <strong>the</strong> community.<br />

It was an eye-opening experience.<br />

Georgia was having a downtime, and I<br />

thought more films would be a good way <strong>to</strong><br />

get more money spent on Georgia.<br />

woodward From Wherever Waters<br />

Flow: Nightlife in Rabun County revolved<br />

around <strong>the</strong> Clay<strong>to</strong>n Dairy Queen and <strong>the</strong><br />

Tiger Drive-in Theatre. The Tiger showed<br />

grade-B films that were so bad <strong>the</strong>y were<br />

actually good entertainment.<br />

reynolds I went <strong>to</strong> Atlanta a lot. I was<br />

dating a lovely lady and driving back at four<br />

in <strong>the</strong> morning <strong>to</strong> work on <strong>the</strong> weekends.<br />

Jon, he probably was out being a horticulturalist.<br />

I think he was testing plants. He’s<br />

always trying <strong>to</strong> fur<strong>the</strong>r his brain.<br />

rickman I was stacking wood out on <strong>the</strong><br />

carport and Burt drove up. I said, “Hold on,<br />

Burt, don’t come and don’t try <strong>to</strong> kiss me,<br />

I’m all sweaty.” He said, “I don’t care.”<br />

terry We went in<strong>to</strong> his house and I<br />

looked over and <strong>the</strong>re’s a big stack of pho<strong>to</strong>graphs<br />

of Burt in a wet suit <strong>to</strong>p. He said,<br />

“Those are for au<strong>to</strong>graphs.”<br />

The direc<strong>to</strong>r and principal ac<strong>to</strong>rs stayed at Kingwood<br />

Country Club & Resort during <strong>the</strong> production,<br />

while <strong>the</strong> crew lodged at <strong>the</strong> Heart of Rabun<br />

Motel. Dickey and Boorman began <strong>to</strong> butt heads.<br />

chris dickey From Summer of<br />

<strong>Deliverance</strong>: My fa<strong>the</strong>r had been handed<br />

<strong>the</strong> shooting script that he thought he’d<br />

approved. But this one started with a terse<br />

note: “Scenes 1–19 omit.” This was going <strong>to</strong><br />

be an action movie that began and ended on<br />

<strong>the</strong> river. Real clean. Real simple.<br />

boorman Film is different from a novel.<br />

terry We were at Kingwood, having<br />

drinks. I was talking <strong>to</strong> Boorman and Jim<br />

1 1 8 | at l a n ta | s e p t e m b e r 2 0 1 1 s e p t e m b e r 2 0 1 1 | at l a n ta | 1 1 9

Dickey comes in drunk. He flops down<br />

and says, “God, <strong>the</strong>y’re ruining my fucking<br />

movie, ain’t <strong>the</strong>y? They’re not doing my<br />

book.” I said, “I don’t know, Jim.” I look at<br />

Boorman, and Jim repeats, “They’re ruining<br />

my book, ain’t <strong>the</strong>y?” Jim grabs me by <strong>the</strong><br />

shoulders and says, “You look at me when I<br />

talk <strong>to</strong> you.”<br />

boorman He was drunk a lot, and he<br />

had become very overbearing with <strong>the</strong><br />

ac<strong>to</strong>rs. Eventually I had <strong>to</strong> ask him <strong>to</strong> leave.<br />

We carried on.<br />

reynolds From his au<strong>to</strong>biography: I just<br />

couldn’t handle his act—his Jim Bowie knife<br />

on his belt, cowboy hat, and fringed jacket.<br />

rickman Boorman and his wife, Christel,<br />

rented a house down at Kingwood, and<br />

boy, she threw <strong>the</strong> best parties. She’d go <strong>to</strong><br />

Atlanta and get a complete hoop of blue<br />

cheese. She also bought all <strong>the</strong> lemons in<br />

<strong>to</strong>wn and made bowls of fresh lemonade<br />

that she <strong>to</strong>ok <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> set. She rode around<br />

Clay<strong>to</strong>n in a yellow convertible.<br />

Conflict with locals began <strong>to</strong> brew. It became<br />

clear that <strong>the</strong> film wasn’t going <strong>to</strong> be a pretty<br />

postcard from North Georgia.<br />

fowler Every character, with <strong>the</strong> exception<br />

of my husband [who played <strong>the</strong> doc<strong>to</strong>r]<br />

and <strong>the</strong> four men going down <strong>the</strong> river, was<br />

portrayed as very limited. And that didn’t<br />

make us feel good.<br />

or something. It was a very happy shoot in<br />

my recollection. Everybody was very collegial.<br />

The locals were extremely helpful.<br />

woodward From Wherever Waters<br />

Flow: Warner Bro<strong>the</strong>rs had found <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

“perfect” backwoods cabin and gas pump<br />

location for shooting <strong>the</strong> “That river don’t<br />

go <strong>to</strong> Aintree” scene. When <strong>the</strong>y returned a<br />

week later, <strong>the</strong>y were met by <strong>the</strong> owner who<br />

quickly sent <strong>the</strong>m packing with, “I just read<br />

<strong>the</strong> book and you’re not shooting that filthy<br />

s<strong>to</strong>ry on my place!”<br />

king The two things that really made<br />

<strong>Deliverance</strong> last are <strong>the</strong> concept of <strong>the</strong> modern<br />

man with <strong>the</strong> primitive weapon against<br />

<strong>the</strong> primitive man with <strong>the</strong> modern weapon.<br />

It was also an unprovoked attack by a rural<br />

element against an urban element.<br />

chris dickey The book and <strong>the</strong> movie<br />

played with <strong>the</strong> tension between <strong>the</strong> new<br />

South and <strong>the</strong> old South. The new South<br />

was Atlanta. The old South up in <strong>the</strong> mountains<br />

was a whole different world. You<br />

didn’t have <strong>to</strong> drive far <strong>to</strong> hit it.<br />

williams The whole his<strong>to</strong>ry of <strong>the</strong><br />

sou<strong>the</strong>rn Appalachians is of impoverished<br />

people in a land that was just abused and<br />

worn out and overrun. That’s why <strong>the</strong>y’re<br />

suspicious. Then, on <strong>to</strong>p of all that suffering,<br />

<strong>to</strong> have someone come in and make fun<br />

of you? They deeply resented it.<br />

boorman Most of <strong>the</strong> people who lived<br />

up <strong>the</strong>re were like that.<br />

chris dickey From Summer of <strong>Deliverance</strong>:<br />

Hollywood paid <strong>the</strong>se people and<br />

treated <strong>the</strong>m as gently as it knew how <strong>to</strong> do,<br />

but it was hard <strong>to</strong> get over <strong>the</strong> feeling as <strong>the</strong><br />

lights went on and <strong>the</strong> cameras rolled that<br />

souls were being s<strong>to</strong>len here.<br />

As <strong>the</strong> production wore on, <strong>the</strong> risk-taking and<br />

off-set drama intensified. Voight climbed hundreds<br />

of feet above Tallulah Gorge, and Reynolds<br />

voluntarily slid down a waterfall.<br />

boorman Jon was in a very depressed<br />

state when I found him; he wanted <strong>to</strong> give<br />

up acting. He says that I saved his life and<br />

<strong>the</strong>n spent <strong>the</strong> whole film trying <strong>to</strong> kill him.<br />

james dickey Letter <strong>to</strong> Jacques de Spoelberch,<br />

who edited <strong>Deliverance</strong> <strong>the</strong> novel, June<br />

26, 1971: Yesterday we were filming <strong>the</strong><br />

part where Ed climbs <strong>the</strong> rock-face, and if<br />

<strong>the</strong>re was ever a harrowing piece of filmmaking,<br />

this was it. Jon Voight did as much<br />

of <strong>the</strong> actual climbing as he was able <strong>to</strong>, and<br />

wanted <strong>to</strong> do more, but Boorman was as<br />

frightened for his life as I was.<br />

I am deathly afraid that somebody will<br />

get hurt on this film, because <strong>the</strong>re is no<br />

doubt that it is <strong>the</strong> most dangerous one ever<br />

made. If we can just get out of <strong>the</strong> gorge.<br />

king The woods represented a sort of<br />

mystery <strong>to</strong> Jim. He wasn’t very comfortable.<br />

They <strong>to</strong>ld me if I got caught in <strong>the</strong> hydro<br />

flow, swim <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> bot<strong>to</strong>m and it’ll shoot you<br />

out. They didn’t tell me that it would shoot<br />

me like a submarine <strong>to</strong>rpedo! They couldn’t<br />

find me for five minutes. A mile down <strong>the</strong><br />

river, <strong>the</strong>y saw this nude man stumbling,<br />

crawling <strong>to</strong>wards <strong>the</strong>m. I’d had on <strong>the</strong>se<br />

high boots and <strong>the</strong>y were gone, <strong>the</strong> pants<br />

were gone, <strong>the</strong> underwear was gone, <strong>the</strong><br />

jacket was gone. I said <strong>to</strong> Boorman, “How’s<br />

it look, John?” He said, “Like a dummy<br />

going over <strong>the</strong> waterfall.”<br />

rickman Frank had built a walkway<br />

and put strong poles and a large rope along<br />

<strong>the</strong> sides of <strong>the</strong> gorge for you <strong>to</strong> hold on <strong>to</strong>.<br />

So <strong>the</strong>re were some precautions.<br />

chris dickey From Summer of <strong>Deliverance</strong>:<br />

To shoot that scene, a little deer was<br />

brought in from an animal park, and heavily<br />

tranquilized so it could be controlled.<br />

There was never any question of hurting<br />

it in any way. But it died. It had been given<br />

an overdose. Boorman and his assistants<br />

were in a quiet panic. “This is all we need,”<br />

I remember one of <strong>the</strong>m saying.<br />

reynolds You think that right in <strong>the</strong><br />

middle of <strong>the</strong> fact that you may be drowning,<br />

somebody’s going <strong>to</strong> say “cut” and<br />

you’re going <strong>to</strong> be all right. I don’t know if<br />

you could find four ac<strong>to</strong>rs quite that crazy<br />

<strong>to</strong> do it now. And Boorman was right <strong>the</strong>re<br />

with us most of <strong>the</strong> time.<br />

terry There were hours of hanging<br />

on <strong>the</strong> branch above a big rapid “waiting<br />

for cloud.” The cinema<strong>to</strong>grapher wanted<br />

everything overcast and <strong>the</strong>n put a brownish<br />

wash on <strong>the</strong> film <strong>to</strong> make it even darker.<br />

It seemed dark enough.<br />

Filming <strong>the</strong> scene in which Ned Beatty’s character<br />

is raped <strong>to</strong>ok more than a day. The set was closed.<br />

chris dickey From Summer of <strong>Deliverance</strong>:<br />

It was a rain forest, right here in <strong>the</strong><br />

mountains of Georgia. Its floor was so shadowed<br />

that small plants found it impossible <strong>to</strong><br />

grow in <strong>the</strong> thick loam of <strong>the</strong> rotting leaves.<br />

The mountain laurel was not shrubbery but<br />

a collection of trees twisted like gnarled fingers<br />

reaching for <strong>the</strong> light. The whole effect<br />

was beautiful and threatening. This was<br />

where <strong>the</strong> rape scene was going <strong>to</strong> be filmed.<br />

The script called it “Resting Place.”<br />

woodward From Wherever Waters<br />

Flow: [Chris] was <strong>to</strong> “stand-in” for Beatty<br />

at all <strong>the</strong> critical marks—climbing <strong>the</strong> leafy<br />

bank, bending over <strong>the</strong> log.<br />

chris dickey Nobody was sure how<br />

far it would go, or how convincing it would<br />

be. I wasn’t in my underwear. I was fully<br />

clo<strong>the</strong>d. But it was a very unpleasant sensation,<br />

lying over a log with your ass up in<br />

<strong>the</strong> air in a scene that’s eventually going <strong>to</strong><br />

be a rape.<br />

rickman Frank [<strong>the</strong> local location scout]<br />

did say that was <strong>the</strong> thing <strong>to</strong> do. And <strong>the</strong>y did<br />

it. Oh gosh. He was proud of it. He thought<br />

saying “squeal like a pig” was real funny.<br />

chris dickey Herbert “Cowboy” Coward<br />

[who plays <strong>the</strong> “Toothless Man” in <strong>the</strong><br />

rape scene] was not an ac<strong>to</strong>r at all. He’d try<br />

<strong>to</strong> get in<strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> role and he would say <strong>the</strong><br />

most ridiculous things. He ends up saying,<br />

“He’s got a real pretty mouth, don’t he?”<br />

williams There was already conflict<br />

between <strong>the</strong> people that traditionally used<br />

<strong>the</strong> river and people coming in from <strong>the</strong><br />

outside. <strong>Deliverance</strong> was like dropping an<br />

a<strong>to</strong>mic bomb on <strong>the</strong> whole thing.<br />

boorman When I was looking for locations<br />

up <strong>the</strong>re, before we shot <strong>the</strong> film, I ran<br />

in<strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> odd guy aiming a shotgun at me.<br />

But on <strong>the</strong> whole, <strong>the</strong>y were very helpful.<br />

chris dickey Life magazine asked my<br />

fa<strong>the</strong>r <strong>to</strong> write something about <strong>the</strong> making<br />

of <strong>the</strong> movie, and he said, “Have my son<br />

write it.” I was nineteen and thought it was<br />

a great chance. So I <strong>to</strong>ok <strong>to</strong>ns of notes and<br />

sat down and wrote a few thousand words.<br />

They didn’t publish it, but I kept <strong>the</strong> notes.<br />

boorman Chris was fourteen years old<br />

I couldn’t get<br />

through <strong>to</strong> my<br />

fa<strong>the</strong>r. All of a<br />

sudden everybody’s<br />

encouraging<br />

you <strong>to</strong><br />

be crazy, harddrinking,<br />

eccentric<br />

. . . you do<br />

that. And he did.<br />

—Chris Dickey<br />

reynolds I was Sou<strong>the</strong>rn, and <strong>the</strong><br />

rest of <strong>the</strong> crew weren’t. I had a real <strong>to</strong>uch<br />

with those people. And not because I was<br />

trying <strong>to</strong> talk like Erskine Caldwell. There<br />

was no way we could have made that movie<br />

without <strong>the</strong>ir permission. They let us shoot.<br />

They weren’t above blowing up canoes.<br />

james dickey Letter <strong>to</strong> Jacques de Spoelberch,<br />

June 26, 1971: Burt Reynolds, who<br />

plays Lewis, cascades down about ninety<br />

feet of hurricane-rushing water. Burt did<br />

this, and <strong>the</strong> shots of him doing it are hairraising<br />

indeed.<br />

reynolds They sent a dummy over<br />

<strong>the</strong> waterfall and it looked like shit, like a<br />

dummy. So I went over <strong>the</strong> waterfall and<br />

hit a rock about a quarter of <strong>the</strong> way down<br />

and cracked my hip bone and my coccyx.<br />

1 2 0 | at l a n ta | s e p t e m b e r 2 0 1 1 s e p t e m b e r 2 0 1 1 | at l a n ta | 1 2 1

But <strong>the</strong> first time <strong>the</strong>y were blocking <strong>the</strong><br />

scene, it was, “I’m gonna lay a big, long<br />

d--- right in your mouth.” Voight laughed.<br />

He looks around and says, “God? Burt?<br />

Somebody?”<br />

reynolds There must be some phallic<br />

thing here: The guy who did <strong>the</strong> raping was<br />

a tree-trimmer.<br />

rickman I didn’t much care for that<br />

scene.<br />

chris dickey From Summer of <strong>Deliverance</strong>:<br />

It was becoming what <strong>the</strong> movie<br />

was about, it was <strong>the</strong> thing everybody was<br />

going <strong>to</strong> remember. Not Lewis’s survivalism,<br />

not <strong>the</strong> climb up <strong>the</strong> cliff, not Ed’s conquest<br />

of his own fear.<br />

terry Chris was put through abuse <strong>to</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> point where when he left for France he<br />

said he’d never come back except <strong>to</strong> see his<br />

stepsister.<br />

chris dickey It was a miserable time<br />

in my life. And my fa<strong>the</strong>r didn’t understand.<br />

james dickey Interview with Playboy,<br />

1973: John turned <strong>to</strong> me and said, “Jim, we<br />

all want you <strong>to</strong> play <strong>the</strong> sheriff.” I said I’d<br />

never acted in my life. “You can do it,” he<br />

said. So I just played myself dressed up in a<br />

sheriff’s uniform. After we made that scene,<br />

I wore <strong>the</strong> uniform back <strong>to</strong> where we were<br />

staying and had dinner. Somebody said <strong>to</strong><br />

me, “Does your sheriff’s outfit fit you OK?”<br />

I said, “Yeah, I haven’t had it off all day. In<br />

fact, ever since I’ve had it on, I’ve been going<br />

around collecting graft from every whorehouse<br />

in Rabun County. And that isn’t all I<br />

got, ei<strong>the</strong>r.”<br />

boorman When I <strong>to</strong>ld him <strong>to</strong> leave, I<br />

said he could come back <strong>to</strong> play <strong>the</strong> sheriff.<br />

He said, “Get yourself ano<strong>the</strong>r boy.” But he<br />

came back, of course. And did very well.<br />

reynolds No, we didn’t take any precautions.<br />

It was crazy. Absolutely crazy. But<br />

we did it and I’m glad we did it. Would I do<br />

it again? Not for three million dollars.<br />

<strong>Deliverance</strong> opened <strong>the</strong> Atlanta International<br />

Film Festival on August 11, 1972, taking <strong>the</strong> <strong>to</strong>p<br />

award, <strong>the</strong> Golden Phoenix. It went on <strong>to</strong> be<br />

nominated for numerous o<strong>the</strong>r awards, includ-<br />

ing an Oscar for Best Picture, Best Film Editing,<br />

and Best Direc<strong>to</strong>r.<br />

williams The book was big. But nobody<br />

had a clue whe<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong> movie would flop. It<br />

just came like a bombshell out of <strong>the</strong> sky.<br />

rickman We went <strong>to</strong> Atlanta for <strong>the</strong><br />

premiere. Frank was in<strong>to</strong> it so deeply, it was<br />

strange for him watching <strong>the</strong> movie. I liked<br />

<strong>the</strong> scenery. But <strong>the</strong> s<strong>to</strong>ry . . .<br />

fowler I still can’t watch it all <strong>the</strong> way<br />

through.<br />

williams The first thing that struck me<br />

was <strong>the</strong> night sounds. What it sounded like<br />

on film was just like walking outside our<br />

house at night.<br />

rickman People said it put a bad picture<br />

of Rabun County <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> world. Like that<br />

rape in <strong>the</strong> woods. I don’t think mountain<br />

people do that.<br />

chris dickey My fa<strong>the</strong>r’s sympathy<br />

with <strong>the</strong>m was much greater than it comes<br />

across in <strong>the</strong> movie.<br />

stan darnell, sixty-two, is <strong>the</strong> head of<br />

<strong>the</strong> Rabun County Board of Commissioners.<br />

He lives in Rabun County. Everybody up here<br />

was kind of up in arms. They didn’t expect<br />

that one scene <strong>to</strong> be in <strong>the</strong>re. But we got <strong>the</strong><br />

rafting industry, and quite a few o<strong>the</strong>r movies<br />

came here and helped real estate, and<br />

o<strong>the</strong>r businesses around.<br />

spivia At <strong>the</strong> premiere, I sat behind Mr.<br />

and Mrs. Carter and Miss Lillian. When<br />

<strong>the</strong> ac<strong>to</strong>r lets out, “Yahoo, that’s <strong>the</strong> wildest<br />

fucking river in <strong>the</strong> world,” I went under<br />

my seat. Jimmy thought it was fine, though.<br />

He always said not <strong>to</strong> inject our feelings<br />

about anybody’s movie. We were <strong>the</strong>re <strong>to</strong><br />

help <strong>the</strong>m.<br />

john dillard, sixty-six, worked for<br />

<strong>the</strong> Dillard Mo<strong>to</strong>r Lodge in Clay<strong>to</strong>n, which<br />

catered for <strong>the</strong> film set. His family now runs <strong>the</strong><br />

Dillard House restaurant in Dillard, Georgia.<br />

Some people that didn’t go <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> trouble of<br />

understanding what Dickey was trying <strong>to</strong><br />

portray may have been offended. He was<br />

showing how people’s character, true character,<br />

comes out when placed in a different<br />

environment, a dangerous environment. It<br />

made for a great s<strong>to</strong>ry.<br />

james dickey Letter <strong>to</strong> William F. Buckley<br />

Jr., September 18, 1972: Have you seen our<br />

movie yet? Has it been reviewed in National<br />

Review? If it hasn’t, I have a suggestion or<br />

two. Most of <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r reviewers have taken<br />

it as a critique of “machismo.” But this<br />

needn’t be <strong>the</strong> case. It can equally be taken<br />

as a political fable: law and order, or un-law<br />

and order (of a sort).<br />

reynolds I’ve always been amazed that<br />

he never wrote ano<strong>the</strong>r book as good. My<br />

<strong>the</strong>ory is that he didn’t have ano<strong>the</strong>r s<strong>to</strong>ry<br />

in him that really happened that dramatic.<br />

james dickey Letter <strong>to</strong> John Boorman,<br />

September 22, 1972: When you see Burt in<br />

London, please have him <strong>to</strong>ne down some<br />

of <strong>the</strong> public remarks he is making about<br />

me. I may be mythical <strong>to</strong> Burt in some way<br />

that has <strong>to</strong> do with his own psychological<br />

condition . . . I don’t think Burt is doing<br />

any of us any good by his creation of this<br />

mythical character he refers <strong>to</strong> under <strong>the</strong><br />

unlikely name of James Dickey. But tell <strong>the</strong><br />

guy that I’m very high on him, for his guts<br />

and talent.<br />

reynolds It <strong>to</strong>tally changed my career.<br />

It changed my life. It changed everything.<br />

james dickey Letter <strong>to</strong> John Foster West,<br />

Oc<strong>to</strong>ber 20, 1972: You could say ei<strong>the</strong>r that<br />

<strong>the</strong> four main characters are more or less<br />

based on people I knew—and still know.<br />

But it would probably be even more true <strong>to</strong><br />

say that <strong>the</strong>y are all aspects of myself.<br />

chris dickey From Summer of <strong>Deliverance</strong>:<br />

The smell of alcohol would ooze<br />

from his pores. And he would stand in <strong>the</strong><br />

long lines—even walk up and down <strong>the</strong><br />

lines—as people waited for tickets. “You see<br />

that?” he’d say. “That’s my movie.”<br />

boorman I was very proud <strong>to</strong> have<br />

made it.<br />

fowler My husband worked one day,<br />

and I still get residuals of $6.14, two or three<br />

times a year.<br />

According <strong>to</strong> U.S. Forest Service statistics,<br />

seventeen people were killed on <strong>the</strong> Chat<strong>to</strong>oga<br />

in <strong>the</strong> four years after <strong>Deliverance</strong> came out.<br />

Raft companies also began sending people down<br />

<strong>the</strong> river.<br />

williams It was referred <strong>to</strong> as “<strong>Deliverance</strong><br />

Syndrome.” Everybody saw <strong>the</strong> movie<br />

and wanted <strong>to</strong> go do what Lewis did. They<br />

came up here ill-prepared and got on a very<br />

dangerous river in a very remote place, and<br />

<strong>the</strong>y got killed in droves; <strong>the</strong>y didn’t have<br />

on life jackets or had no skill whatsoever.<br />

Some died of hypo<strong>the</strong>rmia. I love <strong>the</strong> river,<br />

and I love that people have <strong>the</strong> opportunity<br />

<strong>to</strong> enjoy it. But those brochures call it “The<br />

<strong>Deliverance</strong> River.” Every time I see that,<br />

and all <strong>the</strong> trash, I get nauseated.<br />

dillard Billy Redden, it sort of made a<br />

permanent celebrity out of him.<br />

redden People recognize me in <strong>the</strong><br />

s<strong>to</strong>re. I’ve had people from all over send me<br />

mail. After me and my wife divorced, I had<br />

my address changed, and I ain’t got a check<br />

from Warner Bro<strong>the</strong>rs since. That was<br />

six years ago. They were giving me about<br />

twenty bucks a month. I just want <strong>to</strong> find<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir main office and get my address fixed.<br />

Twenty dollars is a lot, but it’s not worth<br />

fighting my ex-wife for it.<br />

reynolds I wanted <strong>to</strong> hurry up and<br />

get <strong>the</strong> shot before my arms went down<br />

one day. I was pumping iron like crazy, and<br />

Billy came up and said, “Stud, my neighbor<br />

died.” And I said, “Well, I’m sorry, Billy.”<br />

And he said, “She ain’t dead, ’cause I love<br />

her.” And I thought, that’s as good as it gets.<br />

I hope he liked us. We cherished him.<br />

redden He wasn’t that nice. I tried <strong>to</strong><br />

get along with him, but he was kind of a<br />

smart-ass.<br />

chris dickey I couldn’t get through<br />

<strong>to</strong> my fa<strong>the</strong>r anymore, and wouldn’t until<br />

more than twenty years later. If you’re a<br />

writer, your ego is a big part of what you do.<br />

And if all of a sudden everybody’s encouraging<br />

you <strong>to</strong> be crazy, hard-drinking, eccentric<br />

. . . you do that. And he did.<br />

boorman He was appreciative of my<br />

help, and he professed <strong>to</strong> be very happy<br />

with <strong>the</strong> film. He used <strong>to</strong> say <strong>to</strong> people it was<br />

better than <strong>the</strong> book. Later on, he felt that<br />

I, in some ways, had betrayed <strong>the</strong> book. In<br />

<strong>the</strong> late eighties, he tried <strong>to</strong> get Hollywood <strong>to</strong><br />

remake <strong>the</strong> film with his screenplay.<br />

williams He would often say that he<br />

had tremendous regrets about <strong>the</strong> impact of<br />

that book on <strong>the</strong> river that we all loved. The<br />

last thing he said <strong>to</strong> me was, “Say goodbye<br />

<strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> river for me.” And I said, “Why?”<br />

And he never answered.<br />

james dickey Interview with Playboy,<br />

1973: I want <strong>to</strong> be buried on <strong>the</strong> west bank<br />

of <strong>the</strong> Chat<strong>to</strong>oga River—if <strong>the</strong> state will<br />

allow it. Just dumped in<strong>to</strong> a hole with no<br />

coffin. On a plain <strong>to</strong>mbs<strong>to</strong>ne, <strong>the</strong>re’ll be this:<br />

JAMES DICKEY, 1923 TO 19 WHATEVER,<br />

AMERICAN POET AND NOVELIST,<br />

HERE SEEKS HIS DELIVERANCE.<br />

James Dickey died on January 19, 1997, of complications<br />

of lung disease. He was seventy-three.<br />

He is buried on Pawleys Island, South Carolina.<br />

His <strong>to</strong>mbs<strong>to</strong>ne includes <strong>the</strong> final line from his<br />

poem “In <strong>the</strong> Tree House at Night.” It reads, “I<br />

move at <strong>the</strong> heart of <strong>the</strong> world.” n<br />

1 2 2 | at l a n ta | s e p t e m b e r 2 0 1 1 s e p t e m b e r 2 0 1 1 | at l a n ta | 1 2 3