You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

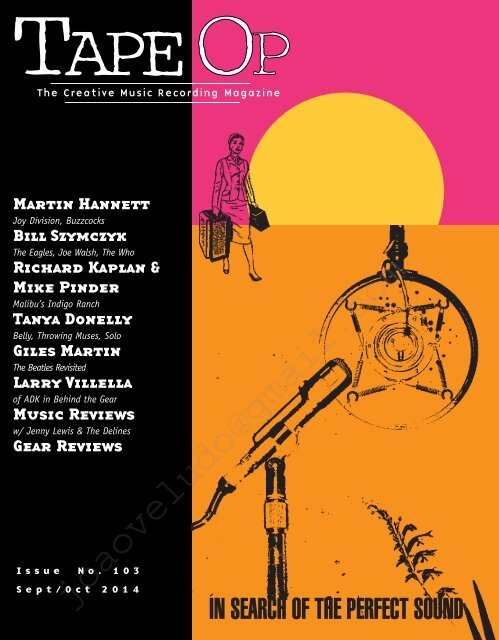

The Creative Music Recording Magazine<br />

Martin Hannett<br />

Joy Division, Buzzcocks<br />

Bill Szymczyk<br />

The Eagles, Joe Walsh, The Who<br />

Richard Kaplan &<br />

Mike Pinder<br />

Malibu’s Indigo Ranch<br />

Tanya Donelly<br />

Belly, Throwing Muses, Solo<br />

Giles Martin<br />

The Beatles Revisited<br />

Larry Villella<br />

of ADK in Behind the Gear<br />

Music Reviews<br />

w/ Jenny Lewis & The Delines<br />

Gear Reviews<br />

Issue No. 103<br />

Sept/Oct 2014<br />

<strong>joaoveludo@gmail</strong>.<strong>com</strong><br />

IN SEARCH OF THE PERFECT SOUND

<strong>joaoveludo@gmail</strong>.<strong>com</strong>

<strong>joaoveludo@gmail</strong>.<strong>com</strong>

<strong>joaoveludo@gmail</strong>.<strong>com</strong>

<strong>joaoveludo@gmail</strong>.<strong>com</strong>

<strong>joaoveludo@gmail</strong>.<strong>com</strong>

Hello and<br />

wel<strong>com</strong>e to<br />

12 Letters<br />

14 Larry Villella in Behind the Gear<br />

18 Tanya Donelly<br />

24 Bill Szymczyk<br />

32 Martin Hannett<br />

42 Richard Kaplan<br />

48 Giles Martin<br />

54 Gear Reviews<br />

80 Music Reviews<br />

82 The Recording Game<br />

Bonus Content:<br />

Richard Kaplan on Bing Crosby’s Tapes<br />

Online Only Feature:<br />

K-Mack<br />

A “Poor Man’s Neve”<br />

Refurbing a Cadac J-type<br />

p a g e<br />

Tape Op<br />

#103!<br />

I arrived at the profession of being<br />

an engineer and producer via being<br />

a fan. Experiences as a listener and music lover sent me on<br />

this path, and certain bits of music pushed me forward. The<br />

tangible feeling I got the first time I heard the masterful<br />

production of Joy Division’s song “Atmosphere” rumbling<br />

through a giant stereo system at a friend’s house sent me on<br />

a quest to absorb more of their music, as well as a desire to<br />

learn how they were made. See our excerpts from Chris<br />

Hewitt’s book on Martin Hannett in this issue for insight<br />

into these iconic Joy Division recordings, and more. A<br />

music fan also has opinions, and while I’ve be<strong>com</strong>e more<br />

relaxed in some of my stances, I still abhor the Eagles.<br />

But I do love Joe Walsh and The Who, so check out our<br />

interview with Bill Szymczyk in these pages! And what<br />

fan doesn’t love The Beatles? Check out the interview<br />

here with Giles Martin, and see how he struggled with<br />

his father’s legacy, Sir George Martin, while proceeding<br />

to make a name for himself. There’s far more in this<br />

issue (did I mention I’m a big Tanya Donelly fan?),<br />

so dig in and enjoy the mag! But first put on some<br />

music you love… - Larry Crane, Editor<br />

<strong>joaoveludo@gmail</strong>.<strong>com</strong><br />

c Don Lewis<br />

right hand LPs courtesy Scott Colburn

<strong>joaoveludo@gmail</strong>.<strong>com</strong>

<strong>joaoveludo@gmail</strong>.<strong>com</strong>

10/Tape Op#103/Masthead<br />

The Creative Music Recording Magazine<br />

Editor<br />

Larry Crane<br />

Publisher &Graphic Design<br />

John Baccigaluppi<br />

Online Publisher<br />

Dave Middleton<br />

Gear Reviews Editor<br />

Andy “Gear Geek” Hong<br />

Production Manager & Assistant Gear Reviews Editor<br />

Scott McChane<br />

Contributing Writers &Photographers<br />

Cover by JB, with endless props to John Van Hamersveld and Bruce Brown.<br />

Garrett Haines, Kraig Mason, Jake Brown Lisi Szymczyk, Chris Hewitt, Gary Lipton,<br />

Jeff Slate, Geoff Stanfield, Eli Crews, Alan Tubbs, Dave Hidek, Dave Cerminara,<br />

Scott Evans, Roy Silverstein, Greg Calbi, Adam Kagan, Adam Monk, Mike Jasper,<br />

Dusty Wakeman, Steve Silverstein and Brandon Miller.<br />

www.tapeop.<strong>com</strong><br />

Dave Middleton and Hillary Johnson<br />

Editorial and Office Assistants<br />

Jenna Crane (proofreading), Thomas Danner (transcription),<br />

Lance Jackman (accounting@tapeop.<strong>com</strong>)<br />

Tape Op Book distribution<br />

c/o www.halleonard.<strong>com</strong><br />

Disclaimer<br />

TAPE OP magazine wants to make clear that the opinions expressed within reviews, letters and<br />

articles are not necessarily the opinions of the publishers. Tape Op is intended as a forum to<br />

advance the art of recording, and there are many choices made along that path.<br />

Editorial Office<br />

(for submissions, letters, CDs for review. CDs for review are also<br />

reviewed in the Sacramento office, address below)<br />

P.O. Box 86409, Portland, OR 97286 voicemail 503-208-4033<br />

editor@tapeop.<strong>com</strong><br />

All unsolicited submissions and letters sent to us be<strong>com</strong>e the property of Tape Op.<br />

Advertising<br />

Pro Audio, Studios & Record Labels: John Baccigaluppi<br />

(916) 444-5241, (john@tapeop.<strong>com</strong>)<br />

Pro Audio & Ad Agencies:<br />

Laura Thurmond/Thurmond Media<br />

512-529-1032, (laura@tapeop.<strong>com</strong>)<br />

Marsha Vdovin<br />

415-420-7273, (marsha@tapeop.<strong>com</strong>)<br />

Printing: Matt Saddler<br />

@ Democrat Printing, Little Rock, AR<br />

Subscriptions are free in the USA:<br />

Subscribe online at tapeop.<strong>com</strong><br />

(Notice: We sometimes rent our subscription list to our advertisers.)<br />

Canadian & Foreign subscriptions, see instructions at www.tapeop.<strong>com</strong><br />

Circulation, Subscription and Address Changes<br />

will be accepted by email or mail only. Please do not telephone. We<br />

have an online change of address form or you can email<br />

or send snail mail to<br />

PO Box 160995. Sacramento, CA 95816<br />

See tapeop.<strong>com</strong> for Back Issue ordering info<br />

Postmaster and all general inquiries to:<br />

Tape Op Magazine, PO Box 160995, Sacramento, CA 95816<br />

(916) 444-5241 | tapeop.<strong>com</strong><br />

Tape Op is published by Single Fin, Inc. (publishing services)<br />

and Jackpot! Recording Studio, Inc. (editorial services)<br />

<strong>joaoveludo@gmail</strong>.<strong>com</strong>

<strong>joaoveludo@gmail</strong>.<strong>com</strong><br />

Please Support Our Advertisers/Tape Op#103/11

I love Tape Op. I can’t believe you got<br />

Al [Schnier, of moe., Tape Op #102]. I was at a<br />

music festival a few weeks ago and somebody<br />

mistook me for Al because we have the<br />

same receding hairline. Thank you.<br />

Tommy McKaughan <br />

My wife and I drove 18 hours back from our<br />

vacation in Florida to our home in Ohio. We got in<br />

at 3 a.m. Our son had put the mail on the floor, and<br />

before we went to bed I saw the newest issue of<br />

Tape Op. My wife said, “Come on, we have been up<br />

for 20 hours.” I said, “I will be in there in a little<br />

bit.” I couldn’t put the latest issue down! I read it<br />

from beginning to end, and finally crawled into bed<br />

at 5 a.m. Honestly, that was my favorite issue yet,<br />

and I am going to do some recording tomorrow.<br />

Thanks for the inspiration!<br />

Kevin R. Bowdler <br />

On the one hand, I <strong>com</strong>pletely agree with Mr.<br />

Baccigaluppi’s recent back page. I am constantly<br />

ranting that I want Cubase and Pro Tools finished,<br />

goddamnit! I want them to be like real musical<br />

instruments: perfected. Sure, one violin or piano<br />

sounds different from the next, and there’s always<br />

room for improvement; but they all work the same<br />

way. Same goes for everything, from Stratocasters to<br />

drill presses. At some point, the consensus was, “This<br />

thing is fully baked.” On the other hand? I can’t<br />

stand where DAW is today. None of them are what I<br />

imagined when I started 15 years ago... which is a<br />

desktop music publisher. None of them are as flexible<br />

as video or desktop publishing programs, in terms of<br />

simply manipulating objects the way Word, InDesign,<br />

or Finale let one cut/copy/paste. None have<br />

particularly great undo. None have version control.<br />

None have an import/export worth a shit. And none<br />

offer any reasonable guarantee that you’ll be able to<br />

open an older project cleanly. I think we are still<br />

stuck in this mental paradigm (which your magazine<br />

promulgates) of “mixer,” “engineer,” and “musician.”<br />

Sound is acquired in one discrete step, mixed in<br />

another, and then mastered in a third. No author in<br />

any other medium thinks in such a formal way<br />

anymore. We’re all constantly creating and editing, all<br />

at the same time. But DAWs continue to be modeled<br />

after tape recorders and mixing desks. In short, I look<br />

forward to the day when there is a simple DAW that<br />

allows me the same flexibility with audio, MIDI, and<br />

notation that I have with words in Microsoft Word;<br />

something that isn’t held back by the look and feel<br />

of a mixing desk.<br />

JC Harris <br />

12/Tape Op#103/Letters/(Fin.)<br />

While I too dream of a<br />

DAW that needs no<br />

upgrades and stays<br />

stable for decades, I<br />

disagree on the criticism<br />

of the “mental<br />

paradigm” that you<br />

believe we “promulgate”<br />

with Tape Op. I think that<br />

many times the division of labor on a recording project<br />

can be a good thing. Sure, a blurring of the lines<br />

constantly occurs (I regularly engineer, produce, mix,<br />

and perform on my studio sessions); but when it <strong>com</strong>es<br />

to the tasks involved in record making, often hiring an<br />

expert can vastly improve the project. Bringing in a<br />

better guitarist than myself is an obvious win. Hiring a<br />

mixing or mastering engineer with more experience<br />

than oneself can improve tracks immensely. Sometimes<br />

records are made in isolation by a single person, and<br />

this can lead to some fantastic, unique results or it can<br />

result in an unbridled mess. Some records are made by<br />

selecting the proper group of talented individuals. But<br />

even inferring that there is only one way to record<br />

music is to miss the point of all the opportunities that<br />

are out there. -LC<br />

I enjoyed John Baccigaluppi’s hammer analogy.<br />

[“Give Me a Hammer” Tape Op #102] I would only<br />

add that the carpenter’s clients probably don’t ask<br />

which brand of hammer he uses...<br />

Frank Dickinson <br />

Issue #102 showed up in my email yesterday. I<br />

love your gear reviews, so I went there first. In my<br />

latest project I have been struggling with two<br />

guitars recorded through a Line 6 Pod 2.0 amp<br />

simulator that seemed okay when I cut the tracks,<br />

but are harsh sounding as I mix. I can barely tame<br />

the sound with <strong>com</strong>pression, EQ, and de-essers. It’s<br />

either too harsh, or too dull, plus the rhythm and<br />

lead guitar have the same frequency range of<br />

splatter and were tough to balance. I read the<br />

review on bx_refinement and within the hour it was<br />

downloaded and in operation. Even my wife could<br />

hear the difference. While I’ll be wary of using the<br />

Pod in the future, I now have a valuable tool that<br />

can really clean things up. Thanks for the<br />

heads up on a great product. It came<br />

along at the right time to rescue my mix.<br />

Jer Hill <br />

I adore this plug-in, and have been using it a lot<br />

to help my recent mixes, even on some tracks I’ve<br />

cut myself. I’m very happy to have turned anyone<br />

on to this fine product. I recently met bx’s<br />

developer, Gebre Waddell, at Summer NAMM, and<br />

am glad to report that he’s an awesome and<br />

interesting person to boot. Expect more miracles<br />

from him in the future. -LC<br />

Send Letters & Questions<br />

to: editor@tapeop.<strong>com</strong><br />

I read several issues ago about Larry Crane<br />

wishing that CDs came with credits in the metadata<br />

for the engineer, producer, studio, etc. When I<br />

create a PMCD [PreMaster CD] for pressing purposes<br />

there is no place except the <strong>com</strong>ments block to add<br />

this information, which is character limited, so<br />

only a fraction of the info I edit in is retained. Also<br />

other info, such as publishing, copywriter, etc. is<br />

not retained after burning the PMCD (I use<br />

MediaMonkey). Is there any other way to add this<br />

info to the metadata that will be retained after<br />

burning the disc? Or am I just pissing up a rope?<br />

Jeffrey Simpson <br />

You are not alone in wondering about metadata on<br />

CDs. Although it is possible to add credits in the <strong>com</strong>ment<br />

section, there are some limitations to this approach. First,<br />

CD Text data is only seen when a disc is played in a CD<br />

Text-enabled car or home player. Portable players and<br />

<strong>com</strong>puters do not read information from the disc (they<br />

pull data from databases, such as Gracenote). The<br />

second, and perhaps more important concern, is that<br />

there is no guarantee that a disc manufacturer will “carry<br />

forward” all of the metadata from the submitted master.<br />

While many plants do pass CD Text through to the<br />

production copies, it is not a universal practice. Even if<br />

you manage to stuff all the <strong>com</strong>ments in, it may not<br />

make it to the finished copies. Presently there is no ideal<br />

solution. This explains some of the recent attempts to<br />

launch album credit sites. The best advice I have is to find<br />

someone who is a Gracenote partner and have them enter<br />

the data for you. Some labels, mastering engineers, and<br />

publishers have enhanced access to production fields in<br />

the Gracenote Database. While anyone can submit song<br />

titles and artists names, via applications like iTunes,<br />

Gracenote Partners have enhanced access to data fields<br />

(e.g. native language, band website, record label, subgenres,<br />

etc.). In particular, we can enter musician,<br />

engineering, writing, and production credits for entire<br />

albums, or even individual songs (very useful on a<br />

<strong>com</strong>pilation release). I believe feeding production credits<br />

into Gracenote is currently our best bet. Even if AES,<br />

NARAS, or some other body manages to push standards<br />

through, online vendors such as Apple, Pono, or Streamerdu-Jour<br />

will more than likely want to pull from an<br />

established data source. In summary: not only are you<br />

pissing up a rope, but you have to get in line to do so.<br />

But so do the rest of us.<br />

Garrett Haines <br />

As always, I was delighted to get the<br />

latest Tape Op [#102]! Right away it flipped open to that<br />

super-sexy shot of Tom Werman standing in front of those<br />

[3M] M79s.Hell yeah! But I'm really writing to express<br />

how impressed I am to see the cover of Family Fun In Tape<br />

Recording used with your opening editorial! This was an<br />

extremely important book for me – please see attached<br />

the review I wrote in 1965 inside the front cover.<br />

“This is a great book! Given November 15, 1965 on my<br />

11th birthday.”<br />

Mitch Easter <br />

<strong>joaoveludo@gmail</strong>.<strong>com</strong>

<strong>joaoveludo@gmail</strong>.<strong>com</strong>

ADK Microphones began in 1997 as<br />

the dream of Larry Villella – recording<br />

engineer, piano expert, and vintage mic<br />

collector – to build quality microphones<br />

for his friends. ADK’s extensive line of<br />

microphones now ranges from very affordable<br />

to top-of-the-line hand-built creations.<br />

I met up with Larry at SuperDigital in<br />

Portland, one of his earliest distributors.<br />

What’s your history with microphones?<br />

In ‘71 I went to recording school in Boston. Eli Lilly’s<br />

grandson, George Lilly, was building Renaissance<br />

Recording Studios in Boston. He went around and<br />

found some academics to create a recording school,<br />

and to teach him how to use all this equipment that<br />

he’d bought. He had a big MCI board and eight brand<br />

new Neumann U 87s mics. They taught us the basics<br />

of recording. We’d take this 8-track Scully [tape deck]<br />

and drag it to old churches to record pipe organs,<br />

harpsichords, and pianos. The instructor came in to<br />

class one day and said, “We’re going to spend the<br />

whole week at The Jazz Workshop recording this new<br />

guy.” We spent five nights with Chick Corea. Jazz<br />

piano recording sort of set my life in motion.<br />

Chick Corea on acoustic piano?<br />

It was the Circle group, which was his avant-garde<br />

group with Anthony Braxton, Dave Holland, and<br />

Barry Altschul.<br />

Some amazing players.<br />

Yeah. In the last three years Dave Holland, Anthony<br />

Braxton, and Chick Corea have all recorded on ADK mics.<br />

Yeah, it <strong>com</strong>es back around!<br />

Forty years later. My life is <strong>com</strong>plete. Chick did a<br />

recording that’s <strong>com</strong>ing out soon with Jazz at Lincoln<br />

Center, and they used a pair of our 3 Zigma lipstick<br />

mics; the SD-C cardioids.<br />

That must be an honor.<br />

If I ever run into Chick Corea again, I’m going to tell<br />

him that he set my life in motion. It’s an honor to<br />

hear some of these tracks, and to know that was what<br />

set out to be my life’s work.<br />

What happened after that?<br />

I moved from Boston to Phoenix, and I worked at the<br />

Electronic Music Labs at Arizona State University. I<br />

had an ARP 2600, a Hagstrom guitar, and a Tandberg<br />

half-track with sel sync. I used to sit there and<br />

strum guitar chords on one channel, dump that track<br />

Behind The Gear<br />

This Issue’s Creator of Capsules<br />

Larry Villella<br />

14/Tape Op#103/Mr. Villella/(continued on page 16)<br />

by Larry Crane<br />

over with some synthesizer lead on the second<br />

channel, and then erase the first channel. I had a<br />

little ad agency where I went around and sold<br />

people ads. I made the music beds, wrote the copy,<br />

and did the voiceover. It actually led to a late-night<br />

FM jazz show I hosted.<br />

When did you move to the Portland area?<br />

I moved to Portland about 15 years ago.<br />

What brought that on?<br />

My wife got a scholarship at Lewis & Clark [College] to<br />

go to graduate school. She now teaches there. We had<br />

really young kids at the time. So I went from working<br />

at the Sherman Clay [Pianos] store in Seattle to<br />

working for the affiliate here in Portland. I sold<br />

Steinways for almost 20 years. By day I was selling<br />

Steinways, and by night I was recording them. In<br />

1997, I just felt like I needed something new that was<br />

all me. I decided to build some microphones for a few<br />

of my friends.<br />

Recording a grand piano is such a<br />

pleasure, and a task.<br />

It’s a daunting task. On five different occasions I<br />

recorded Vladimir Horowitz’s nine-foot concert<br />

Steinway. That was part of the inspiration right<br />

there, trying to figure out how to record a concert<br />

grand piano. I recorded Tom Grant doing jazz, and I<br />

recorded some of the piano professors in Seattle<br />

doing classical.<br />

What was the impetus to build, or<br />

design, your own mics?<br />

There was a Wall Street Journal article. At the time I’d<br />

been collecting mics for 30 years. In a single day, my<br />

[Neumann] U 47 went up $4,000 and the Wall Street<br />

Journal suddenly called them collectable investments.<br />

I had a guy who was going to sell me a [Telefunken]<br />

Ela M 251 for $11,000 and the article said they were<br />

worth $18,000. I called him and said I’d give him<br />

$11,000 for his, but he said, “No. The price went up.”<br />

I got mad. I said that it shouldn’t have to cost $5,000<br />

or $10,000 dollars to have a good sounding mic. I<br />

went to the NAMM show and met some guys in Hall E<br />

that were trying to sell microphones from China. I<br />

took a mic home, and it sounded awful. I literally got<br />

on a plane and flew for 26 hours to meet these guys<br />

in Shanghai. I said, “Listen, this sounds bad. This is<br />

what I want it to sound like.” I showed them a<br />

response curve of a [Neumann] U 67. They sent me a<br />

prototype, and I said, “No.” Three prototypes later,<br />

they were starting to get close. I said, “Okay, build<br />

100 of those.” Rob Schrock [Electronic Musician]<br />

reviewed our initial A-51, and he said, “I was<br />

reminded of a U 67.” We were off to the races. Of<br />

course, a year later the big marketing giants jumped<br />

in and copied our first mic.<br />

What was the price point on that mic?<br />

I think it was $400.<br />

So it was really affordable.<br />

At the time, when I was only buying 100 mics, that was<br />

what it had to be. Now it’s under $200. All of our<br />

designs are proprietary. There’s nothing off the shelf.<br />

We’ve moved from $200 or $300 mics into $1,000,<br />

$2,000, or even $3,000 mics.<br />

You had started out with very affordable mics and<br />

then branched into the higher-end. It seems like a<br />

different trajectory.<br />

If you’re a high-end boutique <strong>com</strong>pany that started out<br />

with a $10,000 mic and then you want to migrate<br />

down into the $1,500 or $2,000 mics, you have the<br />

credibility of your name. But if you’re a little humble<br />

<strong>com</strong>pany, like ADK, starting out with a $300 or $400<br />

mic and you suddenly start to build high-end mics,<br />

credibility is difficult to achieve. Everybody used to<br />

say that it was a great mic for the money. Now, Chuck<br />

Ainlay [Tape Op #97], Bernie Becker, the late Mike<br />

Shipley, all said, “Hey, it’s flat-out good. Period.”<br />

Marketing defies me. People don’t know where to<br />

pigeonhole us. They go, “Who is ADK?” Our $200 mic<br />

sounds good! I don’t build anything I wouldn’t<br />

personally use. I have had people say that they<br />

bought the Thor mic for $400, and if I have anything<br />

better than that, they don’t want to know about it.<br />

Okay, fine! Am I the best bang for the buck under<br />

$500? Am I the surprise in the boutique market? I’ll<br />

let the public and the A-list engineers tell you.<br />

You don’t have a background as an<br />

electrical engineer?<br />

Right. I hire that.<br />

Where do you find people?<br />

I have a mic wizard in Belgium, JP Gerard, who’s my<br />

lead design engineer. He hired an aerospace engineer<br />

PhD from Australia to develop the capsule technology.<br />

I was the middleman, with years of emails going back<br />

and forth. The Australian PhD would say that the spec<br />

was perfect, but JP said that it didn’t sound right, so<br />

he had him do it over. He’s just this little ball of<br />

energy and will not suffer fools gladly. It’s got to be<br />

spot-on. It took us five years to develop the capsule<br />

technology, and then we actually spent another two<br />

and a half years testing which transformer matched<br />

up with which of the five capsules.<br />

Donny Wright here at SuperDigital<br />

showed me the case that has all of the<br />

different 3 Zigma heads and bodies<br />

that you can swap out. He said that<br />

sometimes people will take that<br />

overnight and try to find the <strong>com</strong>bo<br />

that they want for a certain<br />

instrument.<br />

<strong>joaoveludo@gmail</strong>.<strong>com</strong>

<strong>joaoveludo@gmail</strong>.<strong>com</strong><br />

Please Support Our Advertisers/Tape Op#103/15

16/Tape Op#103/Mr. Villella/(Fin.)<br />

Right. The 3 Zigma line has been on the road with Wynton Marsalis for three and a half years<br />

now. They’ve been battle-tested on tour. Our C-LOL-67 lollipop won his quest for the best<br />

saxophone mic. There are about five factories in China putting out about 90 percent of the<br />

microphones in the world today. They may have different brands, but it’s pretty much off<br />

the shelf. ADK doesn’t do business with any of those factories. If you open our microphones<br />

up, you see those giant Wima capacitors. If you look at our high-end mics, we designed the<br />

capsules for them. We put the DNA of the five greatest historical mics into that capsule<br />

design. You don’t need a bunch of extra EQ circuitry to get a tone.<br />

Some mics definitely pull out details in the high-end range that<br />

add clarity, without being shrill.<br />

Right. The real key that we’ve found in our five year saga of developing a capsule is that, with most<br />

everything <strong>com</strong>ing from China, if you put it on a high resolution response curve you see these<br />

little peaky, jagged, sawtooth looking things. It’s not a smooth curve. That’s hell when you’re trying<br />

to EQ, because you want to boost somewhere around 10 kHz, and this one little peak just<br />

skyrockets. There’s that grainy, tizzy, harsh, edgy thing. That’s why we spend all that time<br />

developing our own capsules, to get broadband bell curves, without the jagged edges. That’s why,<br />

if you want a brilliant mic, our C 12 and 251 flavors are brilliant, without harshness. I think that’s<br />

the key. That’s really the heart and soul of what I try to do, to have the microphones be musical.<br />

So how does the <strong>com</strong>pany work, at this point?<br />

We have three factories. There’s the factory that we had built for our high-end 3 Zigma in Asia.<br />

We have a factory that builds our entry-level mics; it’s ISO 9000 and so clean you could eat<br />

off the floor. We also have a small factory near Seattle where we build our high-end products.<br />

The mic you have [Z-67] was handcrafted in the USA. Eighty-five percent of the <strong>com</strong>ponents,<br />

and 90 percent of the labor, is American or European.<br />

People might not know this.<br />

It’s handcrafted in the USA, and by dollars, 85 percent of the <strong>com</strong>ponents in there (like the<br />

Lundahl transformer from Sweden) are European, American, or British.<br />

With three different manufacturing locations, is there a<br />

warehouse somewhere? How do you deal with quality control<br />

and shipping?<br />

I have a warehouse in Ta<strong>com</strong>a, WA. I ship almost everything from there.<br />

What makes ADK unique?<br />

If I have achieved anything, it’s because I’ve been open to criticism. As I said, with Chuck<br />

Ainlay, I gave him mics for 15 years and got criticism and feedback. If I’ve got any strength,<br />

it’s that I’m just a little guy at the hub of a big wheel with spokes going in many directions.<br />

I’m trying to do what I was trained to do in 1971 as a recording engineer – listen. r<br />

<br />

<strong>joaoveludo@gmail</strong>.<strong>com</strong>

<strong>joaoveludo@gmail</strong>.<strong>com</strong>

Tanya Donelly<br />

by Kraig Mason<br />

In 1985, when I was 15 years old, my best friend’s older brother gave<br />

me a cassette tape that said “Throwing Muses Demo” on the label. The<br />

first time I played it I was <strong>com</strong>pletely blown away - it was like nothing<br />

that I had ever heard before. But somehow the fact that the people<br />

that made the music on the tape lived two towns away made it seem<br />

tangible. I was already a home 4-tracker and budding songwriter,<br />

but the existence of this tape made it seem that I could make<br />

“real” music someday as well. Some 28 years later, through<br />

many serendipitous connections, I have had the pleasure of<br />

working with Throwing Muses co-founder Tanya Donelly as a<br />

producer, engineer, and collaborator. Beyond Throwing<br />

Muses, Tanya has been involved in the seminal bands The<br />

Breeders and Belly and has an illustrious solo career.<br />

Can you give me an overview of the Swan<br />

Song Series?<br />

Swan Song Series is a collection of EPs released digitally<br />

through my site and Bandcamp. They are<br />

collaborations, primarily with friends from over the<br />

years, but also with people that I reached out to, such<br />

as authors and other musicians that I admired but<br />

didn’t know. I reached out to them to either write with<br />

me, or play on the music that I was making. There were<br />

also producers that I wanted to work with, such as<br />

yourself. Basically, the inspiration for this came from<br />

the Cabinet of Wonders that my friend John Wesley<br />

Harding puts together. At the end of those nights,<br />

people were reaching out to each other, saying, “ Let’s<br />

write something together.” I followed up on those<br />

conversations almost immediately. The songs I wrote<br />

with Wes, Mary Gaitskill, and Rick Moody came from<br />

those events. From that point I just kept the ball<br />

rolling. That’s where that was all born from.<br />

Were you surprised how the results<br />

came out?<br />

I was, and I wasn’t, surprised. I went into it wanting to<br />

push my own boundaries and do something that felt<br />

more like a village of people making music together.<br />

That came exactly as I expected. I think that what<br />

surprised me was just the fact that when I went into<br />

it, I told everyone not to send me a song that they<br />

thought would sound like me. That was one of my<br />

prerequisites. I’m <strong>com</strong>ing to these people because I<br />

like what they do, so I told them to send me what<br />

they do, not to try to tailor it to what they thought<br />

18/Tape Op#103/Ms. Donelly/(continued on page 20)<br />

might fit me. Everybody pretty much rose to that,<br />

which was a happy surprise for me. I think it made<br />

the whole thing much more joyful and fun. For<br />

instance, if someone sent me words, I wrote music<br />

that I wouldn’t have written in my own lyrical style.<br />

If someone sent me music, then the words that came<br />

out of me would not have <strong>com</strong>e out otherwise. The<br />

whole process was really wonderful and engaging for<br />

me, in a way that I hadn’t really felt in a while. Oddly,<br />

even though it was a massive project with dozens<br />

and dozens of people involved, it ended up feeling<br />

like a real <strong>com</strong>munity project in a way. It feels like a<br />

giant band to me. That’s been really wonderful.<br />

Do you think that the process itself<br />

created results that wouldn’t have<br />

happened, had you gone in a more<br />

traditional direction?<br />

Yes. Part of that is the fact that I wasn’t just writing with<br />

other people. It was also the process of recording<br />

with so many of them. Sometimes I’m in the room<br />

when things are being recorded, and sometimes I’m<br />

not. That was a very different experience. I think<br />

there was more trust. For instance, Jacob Valenzuela<br />

from Calexico plays trumpet on a song called “Making<br />

Light.” He came back with this beautiful, perfect<br />

part. That happened over and over again, and I feel<br />

like it was a very opening experience for me. I think<br />

it’s difficult sometimes, as a songwriter and musician,<br />

to just say, “Here’s my song. Do what you’re going to<br />

do with it and I’ll accept it!” There was not one case<br />

where I did that and was disappointed. I was just<br />

amazed by, and happy with, everything that came<br />

back. It ended up being a very successful experiment.<br />

In a lot of ways, you had to act like a<br />

general contractor for these sessions,<br />

keeping tabs on the songs in<br />

different stages of <strong>com</strong>pletion in<br />

different studios.<br />

I like that. That should be an official musical title.<br />

“General Contractor.” It did feel like that.<br />

You would send me an email and say,<br />

“Hey, are you available on this day?<br />

We’ll do this piece.” Sometimes it was<br />

even for pieces that we weren’t<br />

working on directly.<br />

I will say that the people that I worked with - you, [Paul<br />

Q.] Kolderie [Tape Op #22], and Scott Janovitz - were<br />

people that I already trusted implicitly from the<br />

production and engineering end of things. By putting<br />

it into the hands of engineers and producers who I<br />

could trust, and who I knew were going to get me<br />

something of great quality, I took less risk in that<br />

department.<br />

How many different studios were part of<br />

the project?<br />

Tons of them. A lot of people worked with their home<br />

studios as well and sent tracks in from their homes;<br />

like Chris Ewen did everything at home. It was really<br />

kind of all over the place. Probably eight or nine<br />

studios, at the end of the day. [See sidebar]<br />

What was your methodology for keeping<br />

all of it organized and on time?<br />

<strong>joaoveludo@gmail</strong>.<strong>com</strong>

<strong>joaoveludo@gmail</strong>.<strong>com</strong>

I didn’t have any methodology at all. Any time constraints<br />

were of my own making, so it was very flexible. There<br />

were several times that I delayed a release because I<br />

was waiting for something to be mixed or mastered.<br />

The methodology was all over the place. It really went<br />

song by song. It depended on who was responsible for<br />

what, who was contributing what, and if we were<br />

waiting on a musician to finish a part and send the<br />

track. Every step of the way was just a very daily,<br />

organic process.<br />

No project management software? No<br />

spreadsheets?<br />

None. Nothing like that. Everything came together at Q<br />

Division [Studios], where I mastered half the stuff, and<br />

with Eric Masunaga [Modulus Studios] who mastered half.<br />

I think the tightest one was something like,<br />

“I need this by Saturday.” You were here<br />

on a Thursday, so I still had to mix what<br />

we did with Gail Greenwood [of Belly].<br />

Oh, yeah. The one with Gail was the tightest one. It was<br />

hard to get Gail and I into the room at the same time<br />

for a while. Scheduling wise, not emotionally!<br />

Something you mentioned once stuck<br />

with me. With all the time that you<br />

spent at Fort Apache, it was more than<br />

just a studio. It was like a creative<br />

homebase, and a <strong>com</strong>munity. Was this<br />

a way for you to recreate that?<br />

I hadn’t thought about that; but yes, I think that’s it<br />

exactly. My ideal music making is like the zocalo at the<br />

end of the night, when the whole village <strong>com</strong>es together<br />

and everybody plays at whatever level of talent and<br />

enthusiasm that they are able. I love that feeling. It’s<br />

even greater than being on a team. That’s how the Fort<br />

felt to me. There were so many people invested in it, in<br />

and out of those doors, and I do miss that. That was part<br />

of this too, to pull all those threads together.<br />

As an artist, do you feel that the studio<br />

experience lends itself to your creative<br />

process?<br />

Absolutely. I think that when the Muses were very young<br />

and we were just getting started working with Gary<br />

Smith, in particular, and later [Paul Q.] Kolderie and<br />

[Sean] Slade [Tape Op #22], it was the training ground<br />

for us. Fort Apache was where all the pre-production<br />

happened. That’s where the inspiration came, from<br />

being in the same room, with the same people, day in<br />

and day out, for weeks at a time. It absolutely adds<br />

something. The model of working with another pair of<br />

ears is really important to me. Almost every producer or<br />

engineer we ever worked with was as much a part of<br />

making those albums as we were. We were very open to<br />

suggestions. We started understanding how important<br />

the placement of a mic was, or how you can play with<br />

equipment outside of your own personal gear. That was<br />

illuminating. I absolutely am old school, in terms of<br />

how I feel about studios; as well as the people that<br />

work in them and bring their extra level and layer of<br />

inspiration to a project. I think that <strong>com</strong>es directly from<br />

Gary Smith, I have to say. He’s just very egalitarian<br />

about how he produces, in terms of listening to<br />

everyone in the room. I think that set a template for us<br />

and what we expected from that relationship.<br />

20/Tape Op#103/Ms. Donelly/(continued on page 22)<br />

What you did for Swan Song Series is a lot<br />

different than what you did in the<br />

past, especially with the bands you<br />

were in. Making a Throwing Muses or a<br />

Belly recording, you’re in one place<br />

for a specific amount of time and had<br />

to <strong>com</strong>plete a record.<br />

Right. It’s totally different. This project is not an album. I<br />

never meant for it to be as cohesive and thematic, or for it<br />

to have the same feeling. In fact, I wanted it to be as<br />

scattershot as possible. I feel like with albums, that little<br />

microcosm of both space and time is really important for<br />

making something that sounds and feels like an album.<br />

Clearly this is an arguable point of view, but I personally<br />

feel like the albums that I love as a listener - and the<br />

albums I love that I’ve made - have been this finite thing<br />

where we’re going from one place to another place, we’re<br />

going with these people, and it’s going to be in this room.<br />

You hear that. It’s a whole, enclosed piece when you make<br />

it that way. You have a cohesive thing, as opposed to a<br />

bunch of songs put in one place to listen to. It’s bigger<br />

than that. I think the downside is that you can have<br />

weaker songs that are supported by the stronger one. Now<br />

I feel like the songs really have to be stronger. If you’re<br />

doing everything piece-by-piece, or putting out one song<br />

at a time, they have to be stronger. I’ve been guilty of filler.<br />

It’s like, “Oh, we only have 12 songs. We should have 14.”<br />

“What’s that other song you’ve got?”<br />

“What’s that awful thing that we hated? Let’s do that.”<br />

You’ve worked with some “big name<br />

producers.” Paul Q. Kolderie, Glyn Johns,<br />

Gil Norton, Gary Smith, and Dennis<br />

Herring [Tape Op #48]. Does working with<br />

somebody that is also a star in the<br />

recording world make a difference?<br />

Yes. I think those were all like blind date situations. We<br />

were absolutely set up. I think that it worked out,<br />

particularly with Glyn, who I absolutely love as a<br />

person and a producer. That was a very good match for<br />

us in every way; personality-wise and work-wise. He<br />

brought Jack Joseph [Puig] with him too, which was<br />

great. They were an amazing team, because they<br />

totally <strong>com</strong>plemented each other stylistically. It was<br />

just a great experience.<br />

That record, Belly’s King, was banged<br />

out live?<br />

When we were auditioning and meeting with producers,<br />

Glyn was the only one who said that he thought we<br />

should make a live record. We thought that was<br />

exciting. He said that he’d seen us live and that we<br />

were a great live band. Of course there are layers to<br />

that one somewhat, but for the most part King is<br />

<strong>com</strong>pletely and entirely live. That really appealed to us.<br />

And we were smitten with him, I’ll admit.<br />

Just from your meetings?<br />

From his history, the meetings, and the potential storytelling<br />

hours. I know some people find him prickly, but the way<br />

it translates to me is that he’s honest. He doesn’t pull<br />

punches, but he’s certainly not an unkind man. He never<br />

rubbed me the wrong way at all, not for a second.<br />

That goes back to what you were saying<br />

about having another set of ears that<br />

will be honest with you.<br />

Yes. His pre-production was brutal and necessary. It was<br />

eye-opening. It was interesting to work with someone<br />

who was <strong>com</strong>ing from the perspective of wanting you<br />

to have everything ready to go when you <strong>com</strong>e into the<br />

studio. We spent as much pre-production time with him<br />

as we did recording time. It was really fun, for one<br />

thing. It felt like we were building something. He came<br />

at it looking at whether or not we needed a part, or<br />

whether something was essential. As writers, it’s like,<br />

“Yes, of course it’s essential! That’s the part where I do<br />

this, and that’s so important!” In terms of<br />

craftsmanship, he’s the master. I mean it in the best<br />

possible way. He’s a songwriter’s producer.<br />

What about other producers?<br />

Gil Norton was awesome. He’s wonderful and was a friend<br />

of ours for years on the back of that. I feel that we<br />

[Throwing Muses] went into it quite armored. We were<br />

anxious about what the big, fancy producer was going<br />

to do to us. We were teenagers, so we were nervous.<br />

It’s funny. We just felt like he was trying to<br />

overproduce, putting bells and whistles on. But when I<br />

listen to that record now [Throwing Muses’ self-titled<br />

debut], I think it sounds so much like us. It’s so raw<br />

<strong>com</strong>pared to other stuff. Part of that was us fighting<br />

things that he wanted to do, but a lot of it is because<br />

he was dealing with four very right-out-of-the-cradle<br />

musicians. We were extremely defensive of what we<br />

were doing, as we should have been; but I think that<br />

we overreacted sometimes to certain things. Like<br />

reverb. We were rubbing up against reverb. Now I’m<br />

like, “Juice it up!” At the time, we were also anxious<br />

about everything. But he’s a wonderful producer,<br />

clearly. I don’t think that has to be said.<br />

One of the techniques that you learned,<br />

and have used, is the “rule of four...”<br />

The rule of four! A backup for backups. That was the Kolderie<br />

and Slade trick, where you sing it four times, don’t worry<br />

about what’s <strong>com</strong>ing out, and then listen to all four<br />

together. Most of the time when you blend them it works<br />

out. The edges smooth themselves out, miraculously.<br />

It really does work.<br />

I’ve done it ever since. Another trick that Jack Joseph and<br />

Glyn taught me was that you sing in the control room<br />

with the speakers just perfectly aligned, so that it’s out<br />

of phase where you can’t hear the track in the mic. That<br />

way I don’t have to sing with headphones. I prefer not<br />

to sing with headphones. It depends on the song, but<br />

for the most part I like to hear myself in the room.<br />

That’s a trick I learned from them that I’ve since<br />

applied, but it’s not always the best.<br />

You’ve got to show me how to do that.<br />

Oh god, I don’t know how to do it myself. Talk to Scott<br />

Janovitz. He figured it out for me. You get a tiny bit of<br />

bleed, but I’m willing to sacrifice a little bit of that for<br />

a good vocal, of course.<br />

You like it because you feel like you’re<br />

more in the music itself?<br />

Yes, and because I’m not alone, standing in a room behind<br />

glass. Which is fine too. When I’m singing anything<br />

super personal... everything I do is somewhat<br />

personal... but if I’m singing something that ‘s<br />

potentially upsetting to me, I prefer to be behind glass,<br />

in another room with the headphones on. But<br />

<strong>joaoveludo@gmail</strong>.<strong>com</strong>

<strong>joaoveludo@gmail</strong>.<strong>com</strong>

22/Tape Op#103/Ms. Donelly/(Fin.)<br />

particularly for songs that I have to sing out and really<br />

push, I want to be in the room, with the people, and<br />

have the music in the room with me.<br />

You’d say that we were going to do vocals,<br />

line by line. You’d have specific ideas<br />

about how you wanted to do sessions<br />

going in. As an engineer, that makes<br />

it so easy.<br />

That’s nice to hear.<br />

And then I’d make the face if I thought<br />

that what you were doing was out of<br />

tune.<br />

Yep, every producer’s got a face they make, or a physical<br />

quirk that ac<strong>com</strong>panies that.<br />

You were saying, “I need to be able to see<br />

you so that I know when you don’t like<br />

what I’m doing.”<br />

Exactly!<br />

For the distribution of Swan Song Series<br />

you’re using social media, the<br />

website, and Bandcamp. How is that<br />

working?<br />

I love it. I’ve had many calls for vinyl, but really just a<br />

handful for CDs. I’d be happy to do that, at some<br />

point. I like it because it’s the first time I’ve ever had<br />

product control myself. I don’t mean that in any kind<br />

of micromanaging way. It’s just like having a<br />

boutique. It makes the floating of everything easier<br />

for me. I can budget myself. I know what I’m able to<br />

do and what I’m not. There’s a direct connection to<br />

the people. I love the fact that someone will be like,<br />

“Here’s $5 for the new EP,” and then they can write<br />

me a note! It’s just so folksy and sweet. There’s<br />

something really nice about reading those. I like that<br />

personal transaction. It feels more gratifying to me<br />

right now, at this stage of my life.<br />

Swan Song Series’<br />

Studios Used<br />

Appleman Studio, Stoneham, MA<br />

Plan of a Boy, Providence, RI<br />

Seaside Lounge, Brooklyn, NY<br />

Urban Geek Studio, Brooklyn, NY<br />

Praxis Studio, Athens, Greece<br />

Camp Street Studios, Cambridge, MA<br />

Moontower Studio, Somerville, MA<br />

Q Division Studios, Somerville, MA<br />

Mad Oak Studios, Allston, MA<br />

Modulus Studios, Boston, MA<br />

One Ring Zero Studio, Brooklyn, NY<br />

We need vinyl!<br />

Yeah, vinyl would be cool. And wouldn’t Sue McNally’s<br />

paintings look amazing? That’s 60 percent of why I<br />

want to do vinyl - to get Sue McNally’s paintings in a<br />

tangible form. She’s one of my favorite artists. I think<br />

it would look beautiful.<br />

In my formative years I’d listen to the<br />

music and I’d look at the cover.<br />

Artwork was so important. That’s another way of pulling<br />

people in from your <strong>com</strong>munity that you admire.<br />

Something that broadens the music. Talking about the<br />

artwork was one of my favorite parts of putting an<br />

album together. I have felt like that with the Swan<br />

Song Series. While I’ve felt that satisfaction in having<br />

her piece ac<strong>com</strong>pany each [digital] EP, I would also<br />

like to hold it in my hands.<br />

You’re playing live with Throwing Muses<br />

again. How is that?<br />

It’s been amazing. It’s just been so much fun. It’s this<br />

utopian situation for me, because I get to play my new<br />

stuff, some Belly songs, and then some solo songs. I<br />

get to do this set before the Muses’ set, which is half<br />

catalog and half new stuff, and then I get to play a set<br />

with the Muses! I feel like every night is this<br />

retrospective thing for me. It’s been gratifying. For so<br />

long I avoided playing older songs, or songs that were<br />

too connected to some time in my life that I was still<br />

struggling with. Certain songs represented something<br />

inaccurate, or some inaccurate representation to me.<br />

It’d be too cheesy to do one song, too soon to do<br />

another, or too late to do another. Now I have none of<br />

that baggage left at all, so I’ll play whatever song I<br />

feel like playing. That’s been really wonderful. Playing<br />

with Kristin [Hersh], Dave [Narcizo], and Bernie<br />

[Georges] has been wonderful. I love the people in my<br />

solo band too, so top to bottom it’s been a good<br />

experience. I think that’s what’s nice about it for us is<br />

that it’s a very good balance of everybody<br />

acknowledging that there’s a little bit of nostalgia<br />

involved; but primarily the Muses are playing new<br />

songs, and so am I. We’re feeling like when we do play<br />

the old stuff, it fits in a very nice way and brings the<br />

room together. I think that we have a balance,<br />

material-wise, that makes everyone happy.<br />

You can hear the song itself, but you<br />

can approach it the way that you want<br />

to now.<br />

Yeah. Right. For that reason, I feel like the old stuff fits<br />

in. These old ones are just part of a lifetime’s body of<br />

work. So are the new ones. It just feels good. And<br />

personally, it couldn’t be more fun hanging out with<br />

those guys again.<br />

You’re entering 30 years in the music<br />

business.<br />

I know. What the hell?<br />

What advice to you have for anyone<br />

making music right now?<br />

My advice has always been the same, which is to trust<br />

your instincts and surround yourself with people that<br />

you love and trust. I think you should make sure that<br />

you’re paying attention to your personal muse, as well<br />

as being open to influences that are going to enhance<br />

that; but not to the point where you lose the original<br />

voice. I feel like that advice is timeless. r<br />

<br />

Kraig is at <br />

<strong>joaoveludo@gmail</strong>.<strong>com</strong>

<strong>joaoveludo@gmail</strong>.<strong>com</strong>

Legendary record producer Bill<br />

Szymczyk helped dial in sounds for The<br />

Eagles, Joe Walsh, The James Gang, The Who, Elvin<br />

Bishop, and The J. Geils Band. Many have argued<br />

that AOR [Album-Orientated Rock] radio was<br />

launched on a handful of producers’ – including<br />

Szymczyk’s – watch. His many hits for The Eagles<br />

only add weight to that theory.<br />

Bill’s first big break into the<br />

business as a producer would <strong>com</strong>e courtesy of his<br />

late 1960’s collaboration with blues legend B.B.<br />

King. “The Thrill is Gone’s” title may have<br />

advertised a somber mood, but working side by side<br />

with B.B., Szymczyk remembers the studio vibe as<br />

being just the opposite. “He had a big smile on his face<br />

the first time he heard the first rundown of the mix. This<br />

was following a call I’d made to him at 2 o’clock in the<br />

morning. I’d dialed him up and said, ‘I want to put strings<br />

on this.’ And he said, ‘What?’ Then he said, ‘Well, okay.<br />

I’ll try it.’ Because he believed in me. So I had Bert de<br />

Coteaux, who was my arranger at the time, write a nice<br />

string chart for it. The only thing I told Burt was, ‘I want<br />

it to be dark. I want it to be not joyful in any way; the thrill<br />

is gone. I want it to be a dark string chart.’ He brought it<br />

in and it was hypnotic. B.B. said, ‘I want to <strong>com</strong>e to the<br />

session,’ and I said, ‘Of course, <strong>com</strong>e.’ I was engineering<br />

the string overdubs, and glanced over at him. When he<br />

started smiling, I thought, ‘Okay, I’m good now.’ ”<br />

“When we started recording ‘The Thrill is Gone,’ the<br />

basic track for that was cut as the last tune on maybe a 7 to<br />

11 p.m. session. I think B.B. was playing [his guitar] Lucille<br />

through a Fender amp, and he recorded vocals while he was<br />

playing guitar. I only overdubbed him vocally on one cut,<br />

and that was years later on ‘Hummingbird.’ On B.B.’s<br />

vocal for ‘The Thrill is Gone,’ and others, I tended to use<br />

some echo and some reverb; but nothing like we would do<br />

nowadays, with delays and whatnot. Ahead of the session<br />

starting, we’d sat down in the studio with the players and<br />

worked out the arrangement. He said, ‘Okay, I like this.’<br />

He was all for it, and we did the whole album with my<br />

musicians. ‘The Thrill is Gone’ became one of his biggest<br />

hits. I was just flipping out over that. Working with B.B., I<br />

was thrilled at being able to record a legend, and have<br />

success doing it!”<br />

Following success with B.B. King,<br />

it was the producer’s kindred collaboration with lead<br />

guitarist Joe Walsh and his group The James Gang that<br />

first launched Szymczyk onto ‘70s rock radio. Looking back<br />

by Jake Brown<br />

photo by Lisi Szymczyk<br />

decades later on the sheer serendipity of it all, he hones in<br />

on his central role in discovering, and helping to shape,<br />

the solo career of Joe Walsh; something he counts among<br />

his proudest moments as a producer. “Once I’d had success<br />

with B.B., the record <strong>com</strong>pany said, ‘Maybe you do know<br />

what you’re doing,’ I kept telling them, ‘I want to sign my<br />

own band, because I’m not just a blues guy. I want to make<br />

a rock ‘n’ roll record.’ They said, ‘Okay, go out and find<br />

somebody, and sign them.’ I had a friend of mine who used<br />

to be a roommate in New York, named Dick Korn, who<br />

had moved to Cleveland and was working as the<br />

manager/head bartender at this rock club called Otto’s<br />

Grotto. It was in the basement of the Statler Hotel. He said,<br />

‘Man, there’re a bunch of great acts <strong>com</strong>ing through here.<br />

You’ve gotta <strong>com</strong>e and check some of them out!’ So I<br />

started going to Cleveland, and in the course of three or<br />

four visits, a band called The Tree Stumps – which was an<br />

awful name – came through. The lead singer was Michael<br />

Stanley, and I really liked his tunes and his voice. I signed<br />

them and changed their name to Silk. The next group I<br />

signed was a three-piece, power trio called The James<br />

Gang. I made records with both of them. Silk barely<br />

cracked the charts, but The James Gang got played a lot and<br />

that was the beginning of their career.”<br />

Bill l l Szymczyk Looks l o okS<br />

Back<br />

<strong>joaoveludo@gmail</strong>.<strong>com</strong>

In the early ‘70s, between the James<br />

Gang’s breakout hit “Funk #49,” and later Joe Walsh<br />

solo smashes like “Rocky Mountain Way,” Szymczyk<br />

and Walsh set up shop at the studios of Caribou<br />

Ranch in Colorado. “Joe moved out to Denver just<br />

shortly after I did. He actually moved up to Nederland,<br />

Colorado. We’d heard [producer] Jimmy Guercio – who<br />

I had met a couple times, but not gotten to know very well<br />

– was living just outside Nederland on a huge ranch and<br />

building a studio. Walsh and I went over there and were<br />

astounded at how it looked; it was under construction and<br />

not quite <strong>com</strong>plete. They had a little MCI 400 console<br />

and a 16-track reel machine. There was about a two-year<br />

run where I was up there. It was like inmates running the<br />

asylum, because there was nobody around. If something<br />

broke, we had to fix it – me, my assistant, and whoever the<br />

band was.” Along with recording hits like Rick<br />

Derringer’s “Rock & Roll Hoochie Koo,” Szymczyk’s<br />

personal highlight was the recording of the Walsh’s<br />

“Rocky Mountain Way,” an audio adventure that had<br />

actually begun “when Joe was producing himself at<br />

Criteria [Studios, Miami], where he had done the drums.<br />

He’d done this shuffle track by himself that eventually<br />

turned into ‘Rocky Mountain Way.’ He brought it back<br />

L-R: Bill Szymczyk, B.B. King, Phil Ramone,<br />

backstage at The Village Gate, NY, 1968<br />

and basically we stripped everything off, except the drums,<br />

and started over again – all the bass, kick, piano, the<br />

guitars, and everything. By then he’d had the words, but<br />

when he first cut the track, he was thinking, ‘Let’s just do<br />

this blues-shuffle thing.’ Two to three months later, when<br />

we were working at Caribou, he had the song done, so we<br />

knew exactly how to go about finishing it. Joe liked to layer<br />

his guitar tracks; there’re like six or seven guitars of various<br />

kinds, and the talk box.”<br />

In 1974, Bill caught the ears of the fastrising<br />

group the Eagles. The band recruited<br />

Szymczyk in an effort to shed their softer, country-leaning<br />

side for a harder-edged sound. This was an ambition the<br />

group made obvious from their first introductory meeting,<br />

“Irving Azoff [the Eagles’ manager] set up a meeting<br />

between me and the band. We had dinner and they asked<br />

me questions about rock. I was hesitant about doing it – I<br />

didn’t want to do a ‘cowboy’ band; I wanted to do a rock ‘n’<br />

roll band. When they said, ‘We wanna rock!’ I said, ‘Well<br />

good. If you wanna rock, I’m your man!’ One thing led to<br />

another, and we started working together.”<br />

From session one Szymczyk recalled that “with<br />

the Eagles, my M.O. was to try and keep everything light,<br />

happy, and moving forward, as well as eliminate as much<br />

hassle as possible from outside the control room, and<br />

inside the control room.” From the very first track the<br />

team cut together, “Already Gone,” it was obvious<br />

the chemistry was working, with Bill proudly<br />

pointing to the chart-topper as “the very first cut I did<br />

with them. That was a Jack Tempchin song they brought<br />

in. They said, ‘We’ve been playing around with this for a<br />

while.’ It was a case of, ‘Well, let’s just turn it up and go!’<br />

Glenn Frey had the opportunity to play lead guitar, which<br />

[former producer] Glyn Johns would never let him do,<br />

because it was always Bernie [Leadon]. Bernie was the<br />

country player, and Johns gravitated towards that, as<br />

opposed to Glenn Frey. Frey was not as gifted a musician,<br />

at the time, as Bernie was; but he really had the desire to<br />

rock, so I took a lot of time with him on the guitar solos,<br />

as well as the sounds of the rhythm guitars, and we were off.<br />

I would maybe use one of three different mics on a guitar<br />

amp: a [Shure] SM57, an AKG C414, and a Sennheiser.<br />

I wasn’t double-mic’ing anything in those days, and I<br />

always tracked everybody in the same room, but I would<br />

gobo the amps off from one another. We were recording<br />

at Record Plant Studio A in L.A. – the original 3rd Street<br />

Record Plant. We were recording on a Quad Eight 16-<br />

channel console.”<br />

Mr. Szymczyk/(continued on page 26)/Tape Op#103/25<br />

<strong>joaoveludo@gmail</strong>.<strong>com</strong>

Following the success of albums On<br />

the Border and One of These Nights (a Grammy<br />

winner for Album of the Year in 1975), Szymczyk<br />

and the group – who now included longtime<br />

collaborator Joe Walsh – would embark on their<br />

most ambitious studio adventure yet, as they<br />

headed in to record an album that went on to sell<br />

a staggering 32 million copies. The musical mythos<br />

of Hotel California would revolve around everything<br />

one could expect from the making of an epic album,<br />

beginning with the now legendarily lengthy writing<br />

sessions. “We’d work for three weeks, then take a month<br />

off. During that month off is when Don [Henley] and<br />

Glenn would write lyrics. They had innate talent as<br />

songwriters, and fed off each other brilliantly, much like<br />

Lennon and McCartney. They’d go to each other’s<br />

houses, and then <strong>com</strong>e back to the studio for the next<br />

session with, ‘Well, here it is.’ Glenn and Don, by that<br />

point, both knew who was going to sing lead on what song,<br />

and they would always have decided that prior to cutting<br />

the lead vocal.”<br />

The iconic title track, “Hotel<br />

California,” began after Szymczyk first heard the riff<br />

off, “a cassette of a bunch of Don Felder riffs and ideas.<br />

Don Henley picked up on that. He didn’t have any idea<br />

what the song was going to be about, but said, ‘Let’s work<br />

on this riff for a while.’ During the acoustic introduction<br />

of the song, where Don Felder opens with his signature<br />

riff, he was playing a 12-string, which I recorded with three<br />

mics. My go-to mic for recording acoustic guitar was a<br />

Neumann KM 84 – I’ve used the same one since before<br />

‘Hotel California,’ and I still use it to this day. But Don<br />

had a pickup in his guitar, off to a pair of small Orange<br />

amps, and I mic’d them in stereo. The initial opening<br />

guitar intro is acoustic guitar in the middle, and an amp<br />

on both sides, with a chorus that is flowing back and forth<br />

between the two amps.”<br />

Eventually the producer discovered that to reach<br />

sonic perfection, the song would be recorded by the<br />

band three full times before everyone felt they had<br />

finally gotten the perfect take. He confirms, “We<br />

indeed recorded that track three times! The first time we<br />

did it was too fast, but you’re doing a track, and you have<br />

no idea what the words are, or where they’re going to be.<br />

When Don would start to get an idea about what to write<br />

about, he said, ‘Well, this is going to be too fast. We’ve got<br />

to cut it again.’ So we cut it again. Then he progressed<br />

further with the song’s writing, and next decided it was in<br />

Bill Szymczyk, B.B. King at The Record Plant, L.A., 1970<br />

26/Tape Op#103/Mr. Szymczyk/(continued on page 28)<br />

the wrong key. The third time’s the charm, and that’s the<br />

version that everybody knows. By then, he pretty much had<br />

90% of the lyrics done.”<br />

By the time he was ready to team Felder and<br />

Walsh up as a stereo pair on the song’s outro solo,<br />

the producer remembered feeling Joe’s greatest<br />

assets as a player shone brilliantly alongside<br />

Felder’s own, one that went down over, “a two-day<br />

period working at Criteria Studios. We ran lines out to the<br />

amplifiers in the studio, but they were both performing in<br />

the control room. I was in the middle, Joe Walsh was on<br />

one side, Don Felder was on the other side, and we just<br />

attacked this ending blend of solos. It took us two days, but<br />

it is still one of the highlights of my career. There was a lot<br />

of stop/start and, ‘Let’s try this,’ and, ‘That didn’t work,’<br />

‘Well, if we did this with that, maybe that would work.’<br />

Piece by piece by piece until before it was done. They were<br />

equal gunfighters, Joe and Don.”<br />

Bill joked throughout the process that, “the<br />

console was my weapon.” By the time the team had<br />

declared victory and neared the album’s finish line,<br />

a final flash of inspiration arrived when Walsh and<br />

Henley took the wheel, co-writing “Life in the Fast<br />

Lane.” One of rock radio’s most rotated classics, the<br />

<strong>joaoveludo@gmail</strong>.<strong>com</strong>

<strong>joaoveludo@gmail</strong>.<strong>com</strong>

producer instantly recognized the potential of<br />

Walsh’s riff. “That was Joe’s tune. He brought that lick<br />

in, and Henley wrote the words. By that point in my<br />

working relationship with Joe, when I heard a riff of his, I<br />

could tell when it was a hit riff, and we all jumped on that<br />

one. Most of the lead solo overdubs were done in the<br />

control room, but the original basic track would have been<br />

done with everybody in the studio. Once we started<br />

overdubbing guitars, they would <strong>com</strong>e in one at a time.<br />

But for ‘Life in the Fast Lane,’ that’s all Joe; even though<br />

Felder played some rhythm parts and doubled the lead lick<br />

an octave higher, it was all support to what Joe was doing<br />

on guitar.”<br />

As he wrapped production on what would go on<br />

to be<strong>com</strong>e one of the best-selling rock albums of all<br />

time, Szymczyk had already set his sights on<br />

recording Joe Walsh’s third solo studio album, But<br />

Seriously, Folks... “Life’s Been Good” features<br />

another one of Walsh’s infectious hooks, and the<br />

song was a summary of all the glorious excess of<br />

stardom the Eagles had reached by that point. “To<br />

get the album underway, we rented a 72-foot yacht out of<br />

Miami and went down to the [Florida] Keys with a 4-track<br />

machine and all their instruments. We spent a week down<br />

in the Keys hashing these tunes out. Pretty much<br />

everything on the album was rehearsed on that boat. ‘Life’s<br />

Been Good’ was one of them.”<br />

Bill favored the Neumann U 87 as his, “basic goto<br />

vocal mic, at that point. To me, it was a very high-quality<br />

microphone. Mostly I did not have access to the old U 47s<br />

and the classic Neumanns. I never had any of those, but an<br />

87 was basically a U 67, just with transistors instead of<br />

tubes. It worked great with Joe. There are a bunch of<br />

effects on his vocals for ‘Life’s Been Good.’ On the verses,<br />

there’s a digital delay that’s left and right that is maybe 40<br />

milliseconds on one side, 80 milliseconds on the other.<br />

Then I take that off on the choruses and put a [Cooper]<br />

Time Cube on him.”<br />

In what could have be<strong>com</strong>e one of rock’s greatest<br />

travesties, the producer revealed that the song almost<br />

didn’t make it on the album. “We got back to my studio,<br />

which by this point was set up at Bayshore [Recording<br />

Studios] in Miami. All the way through making the record,<br />

he was getting more and more hesitant about putting this<br />

song out, because he thought the public would take it the<br />

wrong way lyrically. I was the one who was just on him<br />

constantly, saying, ‘No.’ At one point he wasn’t even going<br />

to finish it. I told him, ‘You must finish this. This is a killer<br />

record!’ Finally he agreed, and the rest is history. I did<br />

change a couple of melody lines in it, so it made it easier for<br />

him to sing and gave it more of a lighthearted feeling.<br />

Initially it was (singing in low, slow tone) ‘Life’s been good<br />

to me so far.’ It was a real kind of down and dour, and I<br />

said, ‘You’ve gotta be exuberant there. LIFE’S BEEN<br />

GOOD TO ME SO FAR!’”<br />

It was the end of the 1970s,<br />

and Szymczyk‘s run of successful collaborations<br />

with the Eagles proved true the adage that all good<br />

things must <strong>com</strong>e to an end. The Long Run would<br />

be<strong>com</strong>e the band’s last studio album for almost 25<br />

years. “All the way through the making of Hotel California<br />

everybody was getting along pretty good. But <strong>com</strong>ing off<br />

the heels of the success of Hotel California, among the band<br />

there were a lot of expectations. Everybody was like, ‘How<br />

are we going to top that?’ According to the critics we<br />

didn’t, but in my mind it was a very, very good album – it<br />

just took forever to get done. The pressure was seriously<br />

high, and everybody was getting a little antsy with each<br />

other. That’s when the dissension in the ranks started.<br />

Instead of the old all-for-one/one-for-all, it was, ‘What<br />

about me?’ and a lot of that attitude. They were still a<br />

team, but instead of everybody riding in the same car,<br />

eating together, and staying in the same house, it was two<br />

or three different houses, everybody had their own car,<br />

and it was more standoffish, if you will. But when they got<br />

into the studio, 90 percent of the time we all got along<br />

good and did our work. We would always track together.<br />

We might replace one thing if it didn’t fit later on, but we<br />

would do five-piece, live off the floor all the time.”<br />

One pleasure the producer took great satisfaction in<br />

with the making of The Long Run came with the fact that<br />

he was working on his own turf this time around, allowing<br />

him to maintain a sonic order of sorts. “We recorded that<br />

record mostly at my studio. There were some things done<br />

at Record Plant in L.A, but we did most of it in Miami,<br />

which was the first one we’d recorded at my studio. Hotel<br />

California was done at Criteria and Record Plant. Right as<br />

we were finishing I was building my studio, Bayshore<br />

Recording. It had a relatively dead room, about the same<br />

size as Record Plant Studio A. It was not a huge room, but<br />

it worked really, really well for how I wanted the studio to<br />

sound; regardless of who I was recording. Studios are<br />

people’s personal taste and, at that time, in 1976, we<br />

weren’t doing a lot of live-room stuff; things were still<br />

pretty much dead. It wasn’t until about ten years later that<br />

the big live-room drum sound came into being and<br />

everybody was changing to that. The studio had all the<br />

equipment I wanted as far as outboard gear, which<br />

included a bunch of [Urie] LA-3a and 1176 [limiting<br />

amplifiers], a couple Eventide digital delays and<br />

Harmonizers (which were really, really new at the time),<br />

my old trusty Cooper Time Cube, as well as a MCI<br />

JH-500 Series console. I had a little help in designing<br />

that one, because MCI was right up the street, in<br />

Fort Lauderdale.”<br />

But there was a looming question:<br />

“How do you top Hotel California? That’s the thing I<br />

remember most about The Long Run. Initially it was going<br />

to be a double album. They figured, ‘What if we give<br />

them a double album, and really stretch out?’ We would<br />

cut track, after track, after track. The songwriting modus<br />

operandi was that the music would <strong>com</strong>e first; the lyrics<br />

would <strong>com</strong>e later, to be written to the track. We had<br />

roughly under 20 tracks, but they were in certain stages<br />

of <strong>com</strong>pletion. We were into this album about a year<br />

when they realized, ‘Well, hell, we’re never going to get a<br />

double album.’ So they just concentrated on the ones<br />

that were the most fully lyrically done, and that’s what<br />

turned out to be the final track listing. There are about<br />

eight or nine tracks that are floating around, left over.”<br />

The album satisfied fans, as well as the band’s appetite<br />

for one last go-around, selling seven million copies and<br />

producing three Top 10 singles with “Heartache<br />

Tonight,” “The Long Run,” and “I Can’t Tell You Why.” It’s<br />

a perfect swan song for Bill and the band.<br />

As the 1980’s dawned, Pete<br />

Townshend came knocking on Bill<br />

Szymczyk’s door, offering him what would have<br />

sounded like any producer’s dream gig: producing<br />

The Who’s Face Dances LP. In truth, the band was<br />

having a hard time escaping the dark shadow cast<br />

over them by the recent death of their longtime<br />

drummer, placing their new producer in the<br />

unenviable position of making, “their first album after<br />

Keith Moon had passed away. Kenney Jones was the<br />

drummer, so he and I were the ‘new kids.’ There were the<br />

usual band rifts going on. For instance, they didn’t want to<br />

be around when Roger [Daltrey] was doing vocals, and<br />

Roger never showed up when we were cutting tracks. I’d<br />

have to do each one of them individually, almost. That was<br />

the hardest record I ever had to produce. I worked my ass<br />

off on that.”<br />

“Pete was the reason I did that album. He’s the one that<br />

wanted to hire me.” Szymczyk was able to throw the<br />

notion of a “concept album” out the window. “Pete<br />

brought songs in, and because he did not have a cohesive<br />