Shift-work disorder - myCME.com

Shift-work disorder - myCME.com

Shift-work disorder - myCME.com

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

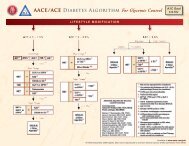

Figure 2 <strong>Shift</strong>-related factors likely to affect attrition in the emergency medical professions<br />

Risk of accidents of<br />

self-harm at <strong>work</strong>, eg,<br />

percutaneous injury<br />

Insomnia<br />

Increased risk of <strong>com</strong>orbidities,<br />

eg, GI <strong>disorder</strong>s, CVD,<br />

depression, and cancer<br />

Risk of traffic accidents,<br />

particularly during the <strong>com</strong>mute<br />

home from <strong>work</strong><br />

<strong>Shift</strong>-related factors<br />

leading to high rates of<br />

attrition in the medical<br />

professions<br />

On-call stress<br />

Excessive sleepiness<br />

Sleep deprivation<br />

Reductions in social<br />

interactions, particularly time<br />

with the family<br />

CVD, cardiovascular disease; GI, gastrointestinal.<br />

Studies of patients with insomnia of unspecified<br />

etiology reveal the extent of the cost burden of this<br />

symptom. An observational US study found that average<br />

6-month total costs (ie, direct and indirect costs) were<br />

approximately $1253 higher for an adult (age 18–64<br />

years) with insomnia than for a matched control without<br />

insomnia. 94<br />

A recently reported Canadian study highlighted the<br />

large contribution of indirect costs to the total costs associated<br />

with insomnia. 95 Direct costs included those<br />

for doctors’ visits, transportation to the visits, and prescription<br />

and over-the-counter drugs. Indirect costs associated<br />

with insomnia included those for lost productivity<br />

and job absenteeism; these accounted for 91% of<br />

all costs. On average, the total annual costs incurred by a<br />

patient with insomnia syndrome (defined as those who<br />

used a sleep-promoting agent ≥3 nights per week and/<br />

or were dissatisfied with sleep, had insomnia symptoms<br />

≥3 nights per week for ≥1 month, and experienced<br />

psychological distress or daytime impairment) 95 were<br />

C$5010 (C$293 direct and C$4717 indirect). For a patient<br />

with insomnia symptoms, average annual total<br />

costs were calculated to be C$1431 (C$160 direct and<br />

C$1271 indirect). By <strong>com</strong>parison, a good sleeper (ie, a<br />

study subject who reported being happy with his or her<br />

sleep, did not report symptoms of insomnia, and did not<br />

use sleep-promoting medication) was found to incur<br />

average annual costs of C$421. 95<br />

More detailed assessment is required of the costs<br />

incurred specifically in patients with SWD, but there is<br />

clearly an economic rationale for early diagnosis and<br />

treatment of the symptoms of SWD.<br />

Summary<br />

What is clear from this review is that, while information<br />

on shift <strong>work</strong> is relatively abundant, data concerning<br />

SWD are meager. For example, epidemiologic data on<br />

SWD are sparse, in part because many investigators in<br />

studies of shift <strong>work</strong>ers do not take the seemingly logical<br />

step of assessing SWD in their subjects. However, differentiating<br />

between shift <strong>work</strong>ers who experience transient<br />

symptoms associated with adapting to a new shift<br />

schedule and individuals with SWD is <strong>com</strong>plex and may<br />

lead to underrecognition of this condition. Similarly,<br />

there are few data on the <strong>com</strong>orbidities experienced by<br />

individuals diagnosed with SWD and further studies are<br />

warranted. The increased risk of illness demonstrated<br />

by shift-<strong>work</strong>ing individuals may be even greater in patients<br />

with SWD due to their intrinsic—and poorly understood—vulnerability<br />

to the effects of shift <strong>work</strong>.<br />

The studies described here show that the burden of<br />

SWD is multifactorial, and it includes impairment of patients’<br />

relationships and health and reduces their efficiency<br />

at <strong>work</strong>. 6 Again, there are very few data on the economic<br />

burden of SWD, although reduced productivity and the<br />

cost of accidents in the <strong>work</strong>place and while driving are<br />

likely to be high. Additional research is needed in this area.<br />

<strong>Shift</strong> <strong>work</strong>ers, including public service <strong>work</strong>ers, must<br />

make difficult decisions during times of day when they<br />

Supplement to The Journal of Family Practice • Vol 59, No 1 / January 2010 S