The Spirit in Human Evolution - Waldorf Research Institute

The Spirit in Human Evolution - Waldorf Research Institute

The Spirit in Human Evolution - Waldorf Research Institute

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

<strong>The</strong> S<br />

pirit <strong>in</strong><br />

<strong>Human</strong> <strong>Evolution</strong><br />

M a r t y n R a w s o n

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Spirit</strong><br />

<strong>in</strong><br />

<strong>Human</strong><br />

<strong>Evolution</strong><br />

by<br />

Martyn Rawson<br />

3

Published by:<br />

<strong>The</strong> Association of <strong>Waldorf</strong> Schools of North America<br />

38 Ma<strong>in</strong> Street<br />

Chatham, NY 12037<br />

© 2003, 2012 by AWSNA Publications<br />

Title: <strong>The</strong> <strong>Spirit</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Evolution</strong><br />

Author: Martyn Rawson<br />

ISBN # 1-888365-45-5<br />

Pr<strong>in</strong>ted <strong>in</strong> the United States of America<br />

Editor: David Mitchell<br />

Proofreader: Ann Erw<strong>in</strong><br />

Graphics Assistant: Ben Hess<br />

Cover: Martyn Rawson and Hallie Wootan<br />

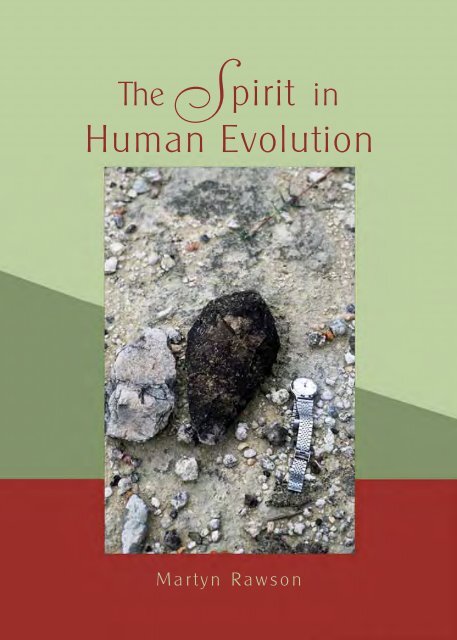

Cover Photo: Martyn Rawson took the photo at Ologorsaile <strong>in</strong> Kenya at noon.<br />

It shows a classic biface handaxe, a core, and a wristwatch to show the scale.<br />

Curriculum Series<br />

<strong>The</strong> Publications Committee of AWSNA is pleased to br<strong>in</strong>g forward this publication<br />

as part of its Curriculum Series. <strong>The</strong> thoughts and ideas rep resented<br />

here<strong>in</strong> are solely those of the au thor and do not necessarily rep re sent any implied<br />

criteria set by AWSNA. It is our <strong>in</strong>tention to stimulate as much writ<strong>in</strong>g<br />

and th<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g as possible about our curriculum, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g di verse views. Please<br />

contact us with feedback on this publication as well as requests for future work.<br />

David S. Mitchell<br />

For AWSNA Publications<br />

4

Table of Contents<br />

Foreword . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 7<br />

Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 11<br />

Chapter 1<br />

Self-Knowledge, Truth and Goodness . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 21<br />

Chapter 2<br />

Contextual Th<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g versus Reductionist Th<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 37<br />

Chapter 3<br />

Anthroposophical Anthropology and the Develop<strong>in</strong>g <strong>Human</strong> Be<strong>in</strong>g. . . . 67<br />

Chapter 4<br />

First Steps . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 95<br />

Chapter 5<br />

Lucy, Flatface and Friends . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 119<br />

Chapter 6<br />

Work<strong>in</strong>g Man . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 169<br />

Chapter 7<br />

<strong>The</strong> Ancients: An Overview . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 213<br />

Chapter 8<br />

<strong>The</strong> Moderns. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 239<br />

Chapter 9<br />

Postscript. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 309<br />

Glossary of Terms . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 311<br />

Bibliography . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 317<br />

5

Foreword<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Evolution</strong> of a Book<br />

A childhood visit to the caves at Altamira left a life-long impression. My feel<strong>in</strong>gs<br />

for the creations of our human ancestors have gradually moved from wonder, through<br />

hobby to serious scientific <strong>in</strong>terest, without ever los<strong>in</strong>g that sense of wonder. I still get a<br />

feel<strong>in</strong>g of awed excitement when I visit a museum of prehistory and even more so when<br />

I get the opportunity to visit prehistoric sites.<br />

My family has got used to my pok<strong>in</strong>g around the edges of ploughed fields, sift<strong>in</strong>g<br />

silt newly washed out among rocks at the entrance to caves, <strong>in</strong> search of pieces of worked<br />

fl<strong>in</strong>t. An uncanny sense draws me to likely sites, a ledge overlook<strong>in</strong>g the curve <strong>in</strong> a river,<br />

an overhang of rock on the side of a valley, the proximity of a spr<strong>in</strong>g. No doubt much of<br />

this is vivid imag<strong>in</strong>ation. Nevertheless, on occasion I have found a scatter<strong>in</strong>g of worked<br />

stone where I expected to. Once while visit<strong>in</strong>g friends <strong>in</strong> southern Germany I came across<br />

a build<strong>in</strong>g site excavation and <strong>in</strong> the pour<strong>in</strong>g ra<strong>in</strong> dug away <strong>in</strong> a trench until the sides<br />

threatened to cave <strong>in</strong>. I came home, covered from head to foot <strong>in</strong> mud, with a piece of<br />

horn scored with rows of notches and several worked stones. Our friends were horrified.<br />

I have collected stone tools for decades. My proudest f<strong>in</strong>d was a wonderful<br />

Acheulean biface/handaxe and a large fossilized tibia of a hippopotamus, which I came<br />

across <strong>in</strong> a spoil heap just outside the compound of the famous site of Olorgesailie <strong>in</strong> the<br />

Kenyan Rift Valley. In full knowledge that the removal of such artifacts is specifically<br />

forbidden, I debated long and hard with myself whether I should take the biface with<br />

me and smuggle it out of the country. I satisfied myself with a photograph and left the<br />

beauty <strong>in</strong> the fork of a small acacia tree for the next archaeologist or pass<strong>in</strong>g tourist to<br />

f<strong>in</strong>d.<br />

I possess a large collection of trac<strong>in</strong>gs and sketches of prehistoric rock art, many<br />

of which I have made <strong>in</strong> situ or <strong>in</strong> museums. Whenever the Rawson family moves house<br />

we take with us large bundles of trac<strong>in</strong>g paper conta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g an extensive record (runn<strong>in</strong>g<br />

<strong>in</strong>to dozens of meters <strong>in</strong> length) await<strong>in</strong>g a suitable display space!<br />

This life-long hobby took on a new dimension when I took a couple of years out<br />

of teach<strong>in</strong>g to do the high school tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g at the <strong>Waldorf</strong> Teacher Tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g Sem<strong>in</strong>ar <strong>in</strong><br />

Stuttgart. <strong>The</strong>re I had the great fortune to have as tutor Wolfgang Schad, now professor<br />

of human evolution at Herdecke University <strong>in</strong> Germany. As an <strong>in</strong>domitable collector<br />

Professor Schad has accumulated an impressive collection of stone tools, casts of hom<strong>in</strong>id<br />

fossils and casts of many works of Ice Age art, to which I had free access. Professor Schad<br />

has moved on but his collection has returned to Stuttgart, and I look forward to renew<strong>in</strong>g<br />

my acqua<strong>in</strong>tance with it when I return <strong>in</strong> the com<strong>in</strong>g year to take up a teach<strong>in</strong>g post at<br />

what is now the Freie Hochschule für <strong>Waldorf</strong> Pädagogik (Independent University for<br />

<strong>Waldorf</strong> Education). <strong>The</strong> reader will f<strong>in</strong>d Professor Schad frequently quoted <strong>in</strong> this book.<br />

7

8<br />

Indeed, given my approach, it would be hard not to. No one has done more <strong>in</strong> this field<br />

than he has. I learned much both from the rigor of his <strong>in</strong>tellect and the warmth of his<br />

enthusiasm. Over the years he has supported and encouraged this present work and<br />

has offered valuable criticism. Over ten years ago I started to compile <strong>in</strong>formation on<br />

human evolution that might be of use to teachers. I was encouraged by the late Georg<br />

Kniebe, who led the Pedägogische Forschungstelle (Educational <strong>Research</strong> Department)<br />

<strong>in</strong> Stuttgart, a position I will shortly have the great honor to assume. He asked me to<br />

draw up a monograph with a bibliography as resource material for High School teachers<br />

<strong>in</strong>terested <strong>in</strong> br<strong>in</strong>g<strong>in</strong>g aspects of human evolution <strong>in</strong>to their lessons. I came as far as<br />

mak<strong>in</strong>g a lengthy presentation to colleagues <strong>in</strong> Stuttgart, but pressure of work prevented<br />

me from produc<strong>in</strong>g the planned resource book. That collection expanded, contracted,<br />

metamorphosed and f<strong>in</strong>ally became someth<strong>in</strong>g quite different.<br />

S<strong>in</strong>ce the literature <strong>in</strong> this field is enormous and more appears all the time, I have<br />

been <strong>in</strong> doubt constantly as to whether there was any po<strong>in</strong>t <strong>in</strong> attempt<strong>in</strong>g to summarize<br />

it. <strong>The</strong> second major concept was to produce a critical review of Rudolf Ste<strong>in</strong>er’s work<br />

on the question of human evolution. What seemed worth attempt<strong>in</strong>g was a comparison<br />

of his work with the results of contemporary research. After a number of years of work, I<br />

eventually produced a massive manuscript conta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g extensive quotations from Ste<strong>in</strong>er<br />

with suggestions as to how this might be <strong>in</strong>terpreted <strong>in</strong> the light of modern anthropology.<br />

<strong>The</strong> publishers sent this to several specialist readers, and Nick Thomas, General Secretary<br />

of the Anthroposophical Society <strong>in</strong> the United K<strong>in</strong>gdom, worked through the text with a<br />

f<strong>in</strong>e-tooth comb. <strong>The</strong> anthroposophical readers found it too scientific, the scientists found<br />

the anthroposophical arguments unconv<strong>in</strong>c<strong>in</strong>g. One reader thought it would make a<br />

good Ph.D. thesis but a bor<strong>in</strong>g book s<strong>in</strong>ce it was so closely argued and supported with<br />

countless references. Such is the process of evolution; “hopeful monsters” have little<br />

chance of survival. An organism either creates a niche for itself or f<strong>in</strong>ds one that suits its<br />

characteristics. This hopeful monster f<strong>in</strong>ally became ext<strong>in</strong>ct as the consequence of a fatal<br />

computer crash, one of those periodic catastrophes that seem to have such an impact on<br />

evolution!<br />

At which po<strong>in</strong>t I decided that what was needed was a totally new approach.<br />

Out went most of the Ste<strong>in</strong>er. In came the <strong>in</strong>tention of mak<strong>in</strong>g the case for anthropology<br />

tak<strong>in</strong>g the human spirit seriously.<br />

It was not vanity or ambition nor, I believe, folly (though elements of all three<br />

can certa<strong>in</strong>ly be found if I look hard enough) that led to the writ<strong>in</strong>g of this book. It<br />

was rather more of a grudg<strong>in</strong>g sense of responsibility. I knew it would be hard work. I<br />

knew I had other more press<strong>in</strong>g responsibilities. I knew it might probably end up <strong>in</strong> a<br />

drawer somewhere, as <strong>in</strong> fact several versions did! I kept hop<strong>in</strong>g that someone better<br />

qualified than I would write what I had to say, thus reliev<strong>in</strong>g me of this obligation. I<br />

would have been disappo<strong>in</strong>ted to have failed by simply runn<strong>in</strong>g out of steam but happy<br />

that the po<strong>in</strong>t had been made. So far I have yet to come across that other book (though<br />

I did get a shock when I saw that Ian Tattersall had published a book called Becom<strong>in</strong>g<br />

<strong>Human</strong>, which had long been my work<strong>in</strong>g title). I readily acknowledge that <strong>in</strong> most<br />

respects I am wholly unqualified to tackle this subject, hav<strong>in</strong>g no academic tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g<br />

<strong>in</strong> any of the fields associated with human evolution, except, that is, education. My<br />

credentials are those of the enthusiastic amateur (a figure not unknown <strong>in</strong> the history<br />

of paleoanthropology). I write this book as a practic<strong>in</strong>g schoolteacher and university<br />

lecturer (<strong>in</strong> child development and education), not as an academic researcher. Teach<strong>in</strong>g<br />

cultural history and human evolution to 14- to 18-year-olds <strong>in</strong> a Ste<strong>in</strong>er <strong>Waldorf</strong> school

and education studies to university students forces one to wrestle daily with some fairly<br />

fundamental questions about the nature of human development. Many of the questions<br />

that led to this book and some of its <strong>in</strong>sights come straight from the classroom.<br />

Along the way many people have helped me <strong>in</strong> large and small ways. I have<br />

mentioned Wolfgang Schad, Georg Kniebe and Nick Thomas. I must add the name of my<br />

mother, Wilma Rawson, who read through the manuscript with her usual constructive<br />

but critical comments. Her scepticism <strong>in</strong> all matters of the spirit made some of this book<br />

a hard read for her but her comments were all the more useful for that.<br />

My thanks also go to the Margaret Wilk<strong>in</strong>son Science Foundation who, long ago<br />

now, provided me with f<strong>in</strong>ancial assistance for some of the research. I would also like<br />

to thank Maria Bargurdjian, Mike Eichner, Freddie Freije, Marianne Harman, Susanne<br />

Ma<strong>in</strong>zer, Richard Masters of the Hermes Trust, Ivor Revere, Rose Schneider and Richard<br />

Zienko, all of whom supported the creation of this book f<strong>in</strong>ancially. My family paid a<br />

price: “Daddy is work<strong>in</strong>g at the computer aga<strong>in</strong>.” But I th<strong>in</strong>k they are proud of me.<br />

David Mitchell at AWSNA Publications also deserves my profound thanks too.<br />

Alongside the countless other tasks he shoulders, he is one of the most creative publishers<br />

with whom I have had the privilege to work. This guy really gets th<strong>in</strong>gs done!<br />

F<strong>in</strong>ally, my thanks go to Nic Poole at Camphill Press, Botton, who first gave me<br />

a computer, a desk and long term encouragement and spiritual support.<br />

– Martyn Rawson<br />

Forest Row, Sussex<br />

Easter 2003<br />

9

Introduction<br />

<strong>The</strong> topic of human evolution has become one of the most excit<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> science. It<br />

also produces a regular stream of popular science books and television series. <strong>The</strong> story<br />

is compell<strong>in</strong>g, the arguments between the ma<strong>in</strong> protagonists vigorous and sometimes<br />

acrimonious. <strong>The</strong> theories beh<strong>in</strong>d this science sw<strong>in</strong>g to and fro with the <strong>in</strong>terpretation<br />

of each new fossil f<strong>in</strong>d to such an extent, that it can bewilder the <strong>in</strong>terested observer.<br />

Yet every new theory has one th<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> common with all the others. <strong>The</strong>y are all bound<br />

with<strong>in</strong> a strictly materialistic paradigm. <strong>The</strong>re is no spiritual <strong>in</strong>terpretation. <strong>The</strong>re is no<br />

spiritual dimension to the issue. Materialism or creationism, or materialistic creationist?<br />

In the other camp, the creationists are marshall<strong>in</strong>g an ever more comprehensive<br />

arsenal of arguments and pseudo-evidence. <strong>The</strong>ir cause is surpris<strong>in</strong>gly popular, as<br />

the strength of the creationist movement <strong>in</strong> the United States demonstrates. Grow<strong>in</strong>g<br />

creationist movements can also be found <strong>in</strong> the Netherlands, Canada, Australia and<br />

New Zealand. Many Islamic countries, of course, have their own version of creationism. 1<br />

In many ways it is hard to understand this, given the rationalist approach we apply to<br />

so many other aspects of life. Of course, there are many shades of creationism, not all<br />

of which are as easy to dismiss from a scientific perspective as fundamentalist Bible<br />

literalism. Creationists often tend to equate Darw<strong>in</strong>ian evolutionary theory with science,<br />

thus polariz<strong>in</strong>g the arguments even further.<br />

Modern creationism has, I th<strong>in</strong>k, emerged (one is tempted to say evolved) <strong>in</strong><br />

response to two basic problems aris<strong>in</strong>g out of the scientific revolution: how to deal with<br />

the question of morality and how to expla<strong>in</strong> God. If humanity has evolved by natural<br />

means from animals, what prevents us from behav<strong>in</strong>g like animals? <strong>The</strong> theological<br />

answer has always been that we were created <strong>in</strong> God’s image and therefore we have some<br />

form of access to div<strong>in</strong>e knowledge, guidance or grace. <strong>The</strong> precondition for receiv<strong>in</strong>g<br />

this gift is faith. Without this we would have no more basis for morality than animals.<br />

<strong>The</strong> second problem is the reverse. Natural laws provid<strong>in</strong>g full explanation of evolution<br />

leave no room for God. If one acknowledges natural evolution, it is not logically possible<br />

to believe <strong>in</strong> a div<strong>in</strong>e creator because such a be<strong>in</strong>g would be entirely redundant.<br />

<strong>The</strong> materialistic view leaves spirituality, let alone div<strong>in</strong>ity, entirely out of<br />

the picture. Creationism on the other hand is an exclusive view that seeks to base all<br />

knowledge on revelation. It says, <strong>in</strong> effect, either believe <strong>in</strong> science or religion.<br />

This is, <strong>in</strong> its way, a totally fatalistic denial of what I would see as the creative,<br />

<strong>in</strong>telligent human spirit. It is true that many people (forty percent of Americans) believe<br />

_________________________<br />

1<br />

See New Scientist, April 22, 2000, for several articles on the subject of creationism as a challenge<br />

to the scientific approach.<br />

11

12<br />

<strong>in</strong> evolution and creationism by argu<strong>in</strong>g that evolution was God’s way of creat<strong>in</strong>g<br />

the world. Yet this is a self‐defeat<strong>in</strong>g argument because it falls back on the old dualist<br />

argument, which says <strong>in</strong> effect, spirit and nature are two parallel universes; we can either<br />

live <strong>in</strong> the one or the other but not both at the same time. So most people believe <strong>in</strong> God<br />

but live their lives accord<strong>in</strong>g to materialistic pr<strong>in</strong>ciples and practice. <strong>The</strong>y live apparently<br />

easily with<strong>in</strong> this paradox.<br />

I would argue that the problem with both of these positions is their <strong>in</strong>ability to see<br />

that spirit and nature are one <strong>in</strong>tegrated unity. This is to say that biology and culture are<br />

not parallel universes and that evolution and history are not consecutive, that is, history<br />

does not take over where evolution ends for all <strong>in</strong>tent and purposes. Phylogeny, the<br />

evolution of species, and ontogeny, the maturation of <strong>in</strong>dividuals, are both expressions<br />

of a developmental process. Nor do nature (<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g human be<strong>in</strong>gs) and knowledge<br />

have to be seen as separate worlds but can be thought of as <strong>in</strong>tegrated, the latter be<strong>in</strong>g<br />

a state of the former (or vice versa).<br />

My purpose here is to go beyond all dualistic approaches of m<strong>in</strong>d and matter<br />

and to seek a path towards the possibility of understand<strong>in</strong>g the universe as an <strong>in</strong>tegrated<br />

whole. As I see it, there are two fundamental obstacles to this path.<br />

<strong>The</strong> first is materialism (especially <strong>in</strong> its mechanistic/reductionist form), the<br />

second is any form of dualism, either based on faith <strong>in</strong> div<strong>in</strong>e creation or based on the<br />

philosophical cop-out summarized <strong>in</strong> the Lat<strong>in</strong> word ignorabimbus (we cannot know)<br />

<strong>in</strong> other words, the m<strong>in</strong>d can never know own its true nature. Our means of know<strong>in</strong>g<br />

this unity are, and have to be, scientific, but a scientific method that does not preclude<br />

a recognition of spiritual factors. <strong>The</strong> ma<strong>in</strong> argument of this book is that recogniz<strong>in</strong>g<br />

spiritual factors is important if our understand<strong>in</strong>g of human nature and human evolution<br />

is to make sense of who we are. Only the spiritual dimension can complete the picture<br />

provided by genetics, psychology and anthropology. I argue that the image of the human<br />

be<strong>in</strong>g currently provided by materialistic science is fragmented and fails to provide us<br />

with an adequate basis for any real sense of mean<strong>in</strong>g. As a teacher I am concerned with<br />

giv<strong>in</strong>g young people a range of options, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g the possibility that humank<strong>in</strong>d can<br />

and does develop out of its <strong>in</strong>ner resources. By tak<strong>in</strong>g a developmental approach, we<br />

can overcome the problem of mechanistic reductionism and, I believe, beg<strong>in</strong> to deal with<br />

dualism. Only through the recognition of truly developmental processes can we beg<strong>in</strong><br />

to f<strong>in</strong>d an objectively possible basis to th<strong>in</strong>k about spiritual factors. Briefly my argument<br />

will be as follows: the human be<strong>in</strong>g (<strong>in</strong>deed any organism) has a history of growth and<br />

development with<strong>in</strong> a context. That context comprises an entire field of relationships. <strong>The</strong><br />

<strong>in</strong>dividual is the locus of development with such a field. <strong>The</strong> field <strong>in</strong>cludes relationships<br />

not only with the external environment, physical, biological and social—but also the<br />

<strong>in</strong>ternal environment—genetic, biological, psychological—and, I argue, the spiritual<br />

environment, which has its personal and universal aspects.<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>in</strong>dividual (and this goes for fruit flies, beavers and humans alike) is not<br />

merely the sum of an unfold<strong>in</strong>g predeterm<strong>in</strong>ed plan nor the product of environmental<br />

<strong>in</strong>fluences but possesses a real history (or rather biography) and yet bears with<strong>in</strong> it the<br />

scope for future potential. <strong>The</strong> <strong>in</strong>dividual is always translat<strong>in</strong>g its real past history <strong>in</strong>to<br />

its own future <strong>in</strong> context. <strong>The</strong> differences between fruit fly, beaver and human lie <strong>in</strong> the<br />

degree to which the <strong>in</strong>dividual can respond to the challenges of translat<strong>in</strong>g the past <strong>in</strong>to<br />

the future. <strong>The</strong>y lie <strong>in</strong> the scope for self-determ<strong>in</strong>ed development.

<strong>Spirit</strong>ual Selection<br />

<strong>The</strong>re is an alternative way of view<strong>in</strong>g human development and evolution<br />

that recognizes more than bl<strong>in</strong>d natural selection and selfish genes. This also goes<br />

beyond even the subtleties of the gene-environment feedback loop or the possibilities<br />

of gene-culture co-evolution. It <strong>in</strong>cludes the possibility that the <strong>in</strong>dividual can override<br />

such determ<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g factors and <strong>in</strong>fluence his or her own development <strong>in</strong> unique ways.<br />

For humanity as a whole this alternative view suggests a spiritual-<strong>in</strong>dividualiz<strong>in</strong>g<br />

selection parallel to and <strong>in</strong>teract<strong>in</strong>g with the forces of natural selection. This “spiritual<br />

selection” is at the same time a progressive trend towards the emancipation of the<br />

<strong>in</strong>dividual from all forms of determ<strong>in</strong>ism. As an evolutionary dynamic it has always<br />

been and rema<strong>in</strong>s a trend towards the expression and revelation of potential. This<br />

potential does not have its orig<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong> a predeterm<strong>in</strong>ed model but <strong>in</strong> a lived past, <strong>in</strong><br />

a history. Ultimately it is also a trend that creates the possibility for the <strong>in</strong>dividual<br />

human be<strong>in</strong>g to free him- or herself from the all cultural imperatives. It is a path of<br />

freedom and ethical <strong>in</strong>dividualism.<br />

This approach sees development itself as someth<strong>in</strong>g more than mere change,<br />

adaptation and growth. It sees development as the progressive emergence of an <strong>in</strong>ner<br />

determ<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g pr<strong>in</strong>ciple encounter<strong>in</strong>g and striv<strong>in</strong>g to <strong>in</strong>dividualize what it has <strong>in</strong>herited<br />

and what it meets <strong>in</strong> the world <strong>in</strong> order to come to ever more coherent form, to ever more<br />

complete expression. This pr<strong>in</strong>ciple of be<strong>in</strong>g exists <strong>in</strong> the form of potential. It can only<br />

come to realized form by virtue of natural means. Be<strong>in</strong>g can only become through life<br />

and life can only manifest <strong>in</strong> physical, biological form.<br />

This <strong>in</strong>ner pr<strong>in</strong>ciple is spirit. <strong>Spirit</strong> comes to <strong>in</strong>dividualized form through the birth<br />

and development of human be<strong>in</strong>gs. We see this <strong>in</strong> the development of each <strong>in</strong>dividual<br />

child. It is the manifest reality of the <strong>in</strong>dividual human spirit that gives us the clue to<br />

human evolution. Here is no simplistic form of recapitulation theory, nor a version of<br />

Haeckel’s’s biogenetic law 2 that states that ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny. <strong>The</strong> l<strong>in</strong>k<br />

between the development of the <strong>in</strong>dividual and the species is the concept of development<br />

I have sketched above. In both cases there is an <strong>in</strong>ner pr<strong>in</strong>ciple seek<strong>in</strong>g to come <strong>in</strong>to be<strong>in</strong>g.<br />

That means the existence of <strong>in</strong>tention act<strong>in</strong>g with<strong>in</strong> both development and evolution,<br />

though not necessarily consciously. <strong>The</strong> nature of such <strong>in</strong>tention is ak<strong>in</strong> to a natural law<br />

of be<strong>in</strong>g.<br />

I can see evolutionists chok<strong>in</strong>g on this idea of <strong>in</strong>tention <strong>in</strong> nature. However,<br />

what is the will or <strong>in</strong>st<strong>in</strong>ct to live and reproduce if it is not a k<strong>in</strong>d of motivat<strong>in</strong>g, though<br />

unconscious, <strong>in</strong>tention? As soon as the environment or the ecological context changes,<br />

that <strong>in</strong>tention to survive becomes a selective pressure. That is naturally not the same as an<br />

organism <strong>in</strong>fluenc<strong>in</strong>g the emergence of any new trait. No amount of will can do that. Yet<br />

an organism’s capacity to change, through whatever mechanism, is a form of plasticity.<br />

This plasticity already implies that the organism possesses greater potential than it has<br />

thus far manifested <strong>in</strong> actual forms or behavioral traits.<br />

Life is imbued with be<strong>in</strong>g and therefore with <strong>in</strong>tention. In the case of organisms<br />

striv<strong>in</strong>g to live, grow and reproduce, one could call this bl<strong>in</strong>d <strong>in</strong>tention. All liv<strong>in</strong>g be<strong>in</strong>gs<br />

possess greater (bl<strong>in</strong>d) potential than can be realized at any given moment. Were this<br />

_________________________<br />

2<br />

Pioneer biologist Ernst Haeckel (1834–1909) became a champion of Darw<strong>in</strong>’s theory of evolution.<br />

His work on morphology and anatomy led him to def<strong>in</strong>e his biogenetic law. Ontogeny is the<br />

developmental history of the <strong>in</strong>dividual organism (dur<strong>in</strong>g embryogenesis); phylogeny is the<br />

evolutionary history of the species.<br />

13

not the case development could not occur. <strong>The</strong> liv<strong>in</strong>g world uses many mechanisms<br />

to express this <strong>in</strong>tention of development; the best known of these is that of adaptation<br />

through natural selection. We tend to forget the other side to the natural selection co<strong>in</strong>,<br />

namely that of nature’s abundance. Were nature not fecund, full of potential, there would<br />

be no scope for natural selection to function. With<strong>in</strong> this process are many subtleties,<br />

certa<strong>in</strong>ly not all of which have been discovered and recognized by biology. As our<br />

understand<strong>in</strong>g of the vastly complex nature of biodiversity, ecology and evolution<br />

expands, so too will our recognition of the variety of mechanisms by which organisms<br />

develop.<br />

Change and Potential<br />

Change creates developmental opportunity. <strong>The</strong> fact that naturally generated<br />

organisms are not clones and cont<strong>in</strong>uously br<strong>in</strong>g forth variation—an expression not only<br />

of vitality but of potential—means that the potential for development, through adaptation<br />

or exaptation (discussed <strong>in</strong> Chapter 2), is an active <strong>in</strong>ner pr<strong>in</strong>ciple. Complexity has the<br />

tendency to leap beyond itself, to become more than the sum of its parts. <strong>The</strong> appearance<br />

of all the major organs and traits that have contributed to the story of human evolution,<br />

upright bipedal walk<strong>in</strong>g, tool mak<strong>in</strong>g, cognitive development, language, even the eye<br />

and ear, reveal this quality of becom<strong>in</strong>g someth<strong>in</strong>g qualitatively more than the sum of<br />

their parts.<br />

Long processes of evolution from simple to complex have borne with<strong>in</strong> them<br />

latent qualities that have emerged, often suddenly at certa<strong>in</strong> critical po<strong>in</strong>ts. It is these<br />

emergent qualities that we need to identify if we wish to grasp what I am referr<strong>in</strong>g to<br />

as <strong>in</strong>tention. Perhaps we will discover this when the laws of the developmental history<br />

of the <strong>in</strong>dividual organism (dur<strong>in</strong>g its embryogenesis) and phylogeny, the evolutionary<br />

history of the species complexity, are more fully grasped. I would suggest that this<br />

complexity has <strong>in</strong>herently emergent properties.<br />

<strong>Human</strong> be<strong>in</strong>gs certa<strong>in</strong>ly conform to all the known laws of biological evolution.<br />

But we have also evolved abilities not possessed by other organisms, and these make it<br />

possible for human development and human evolution to <strong>in</strong>fluence the process <strong>in</strong> unique<br />

ways. Foremost of these abilities are the faculties of speech, th<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g, self-consciousness<br />

and free will. <strong>The</strong>se abilities have contributed to what we generally term culture, and<br />

culture is a formative process, which, whatever biological underp<strong>in</strong>n<strong>in</strong>g it also possesses,<br />

is essentially a product of the human spirit. Culture, as an expression of and a medium<br />

for the human spirit, is no longer bl<strong>in</strong>d <strong>in</strong>tention. Culture has obviously become a means<br />

by which human be<strong>in</strong>gs evolve and develop.<br />

<strong>Spirit</strong> Made Flesh<br />

<strong>Human</strong> evolution reveals the progressive emergence of faculties <strong>in</strong> human<br />

ancestors that led to an <strong>in</strong>dividualization process <strong>in</strong> which the human spirit arose <strong>in</strong> and<br />

through hom<strong>in</strong>id “flesh,” that is to say spirit <strong>in</strong>carnated <strong>in</strong> matter. This process reveals<br />

itself <strong>in</strong> stages of emancipation from a purely biological to an <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>gly cultural<br />

determ<strong>in</strong>ation. Yet rather than try to reduce the orig<strong>in</strong>s of cultural evolution to genetically<br />

prescribed behaviors selected by factors of population mechanics, we should see culture<br />

and nature <strong>in</strong> a far more <strong>in</strong>tegrated way. That is, not <strong>in</strong> the reductionist way of Neo-<br />

Darw<strong>in</strong>ist biology, evolutionary psychology and anthropology. This way can expla<strong>in</strong> a<br />

lot about this process of transformation, but not all.<br />

While important aspects of human nature and behavior can be expla<strong>in</strong>ed by the<br />

methods of these sciences, there are limits to their scope. <strong>The</strong> reason for this is that human<br />

14

nature itself has outgrown the realms that such methods can <strong>in</strong>vestigate. Nor does the<br />

story end here because human be<strong>in</strong>gs now have the further potential to <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>gly<br />

emancipate themselves even from cultural determ<strong>in</strong>ants through their own <strong>in</strong>ner<br />

endeavors. <strong>The</strong> develop<strong>in</strong>g human be<strong>in</strong>g can atta<strong>in</strong> a state of relative <strong>in</strong>ner freedom. I do<br />

not have to follow the dictates of my selfish genes, nor even be swayed by my <strong>in</strong>st<strong>in</strong>ctive<br />

reactions of fear and loath<strong>in</strong>g, though unfortunately, I can and clearly do follow them at<br />

times. I can love my neighbor—or at least aspire to.<br />

Rudolf Ste<strong>in</strong>er<br />

In develop<strong>in</strong>g this tra<strong>in</strong> of thought I follow the ideas of Rudolf Ste<strong>in</strong>er (1860–<br />

1924), the Austrian philosopher, spiritual teacher, and founder of the worldwide<br />

educational movement usually referred to as Ste<strong>in</strong>er or <strong>Waldorf</strong> education. Ste<strong>in</strong>er’s work<br />

also forms the basis for a complementary medical approach with many hospitals, cl<strong>in</strong>ics<br />

and therapeutic centres, the biodynamic agriculture movement, <strong>in</strong>fluential organizational<br />

development consultancies and many other fields of human endeavour.<br />

Ste<strong>in</strong>er taught that by follow<strong>in</strong>g a modern path of spiritual development, the<br />

<strong>in</strong>dividual can atta<strong>in</strong> degrees of freedom from <strong>in</strong>ner and outer determ<strong>in</strong>ation. Know<strong>in</strong>g<br />

that this is possible is essential if we are to f<strong>in</strong>d not only hope but also mean<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> our<br />

lives. Only out of some degree of <strong>in</strong>ner freedom can a human be<strong>in</strong>g make the k<strong>in</strong>d of<br />

choices that are essential to social and ecological stability, if not actually to harmony. That<br />

is the goal. As I see it, only a conscious recognition and understand<strong>in</strong>g of the spiritual<br />

potential <strong>in</strong> each person can release the potential to do good. And the world needs us to<br />

do good. Faith alone no longer helps. We must th<strong>in</strong>k it through on the basis of our own<br />

observations. We must base our actions on <strong>in</strong>sight.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Right Methods and the Right Questions<br />

How are we to recognize this spiritual-<strong>in</strong>dividual factor? Indeed how do we<br />

know at all what it is to be human? Here lies a key problem of methodology that poses<br />

epistemological questions. To understand the soul-spiritual aspect of human nature<br />

requires a different methodology than that appropriate for observ<strong>in</strong>g the bodily processes<br />

and <strong>in</strong>st<strong>in</strong>cts. Ultimately we can only know the human be<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>tuitively through direct<br />

mutual recognition. However this does not preclude our form<strong>in</strong>g pictures of the qualities<br />

that come to expression through the human be<strong>in</strong>g.<br />

Attempt<strong>in</strong>g to understand human nature <strong>in</strong> the same way that we try to<br />

understand other natural phenomena, that is by <strong>in</strong>terpret<strong>in</strong>g what is revealed through<br />

the senses (and their <strong>in</strong>strumental extensions), is too limited an approach. It is like try<strong>in</strong>g<br />

to understand a pa<strong>in</strong>t<strong>in</strong>g by analyz<strong>in</strong>g the chemistry of the pa<strong>in</strong>t and the physical forces<br />

that cause the pa<strong>in</strong>t to b<strong>in</strong>d to the canvas. <strong>The</strong> pa<strong>in</strong>t<strong>in</strong>g is of a pictorial nature. This means<br />

that its content, its iconography, its message, its aura, the overall impression it makes on<br />

us <strong>in</strong> a holistic way, is not sense perceptible. It has to be <strong>in</strong>tuitively and imag<strong>in</strong>atively<br />

grasped.<br />

When we observe a human be<strong>in</strong>g, the physical appearance and behavior reveal<br />

only certa<strong>in</strong> aspects of the <strong>in</strong>ner nature of that <strong>in</strong>dividual, not the whole be<strong>in</strong>g. What we<br />

perceive are symptoms. Unlike a pa<strong>in</strong>t<strong>in</strong>g, a human be<strong>in</strong>g is cont<strong>in</strong>uously <strong>in</strong> a state of<br />

change. <strong>The</strong> picture revealed to our <strong>in</strong>sight is not a static one but one cont<strong>in</strong>ually <strong>in</strong> the<br />

process of becom<strong>in</strong>g. Individuals develop, which, as we have seen above, means that<br />

they are <strong>in</strong> a process <strong>in</strong> which their <strong>in</strong>ner nature is actively seek<strong>in</strong>g to come to expression<br />

or, depend<strong>in</strong>g on the circumstances, withdraw<strong>in</strong>g. Furthermore, beh<strong>in</strong>d what comes<br />

15

to expression <strong>in</strong> the develop<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>dividual is a creative process of formative forces. In<br />

our metaphor 3 of the pa<strong>in</strong>t<strong>in</strong>g, this would be like stand<strong>in</strong>g before a blank canvas with<br />

pa<strong>in</strong>ts and brushes ready for use and observ<strong>in</strong>g the artist <strong>in</strong> the process of conceiv<strong>in</strong>g<br />

the picture. <strong>The</strong> creative activity implicit <strong>in</strong> such a situation is equivalent to human<br />

<strong>in</strong>tentions.<br />

If we are to understand the human be<strong>in</strong>g, we can only do so by recogniz<strong>in</strong>g this<br />

iconic aspect of human nature and proceed accord<strong>in</strong>gly. We can “read” the human be<strong>in</strong>g<br />

only <strong>in</strong> the form of images, of pictures that express processes not visible to us. <strong>The</strong> same<br />

is true if I wish to recognize general processes with<strong>in</strong> groups of people at particular times<br />

<strong>in</strong> history or prehistory. Perceiv<strong>in</strong>g the soul-spirit nature of the human be<strong>in</strong>g requires<br />

quite different abilities than observ<strong>in</strong>g physical or biological processes. We have to ask<br />

not only how did this come to be but also what comes to expression.<br />

To answer these questions we are likely to get further with our <strong>in</strong>tuition than with<br />

our rational <strong>in</strong>tellect. In a way it does seem odd to have to try to justify recognition of the<br />

spiritual <strong>in</strong> the human m<strong>in</strong>d. One could simply list dozens of great artists and ask, Are<br />

their achievements <strong>in</strong> their chosen media biologically or physically explicable? What is<br />

art about, if not the spiritual? What is creativity anyway, whether <strong>in</strong> science or art? Does<br />

it not <strong>in</strong>volve some level of <strong>in</strong>tuitive, spiritual activity? But I realize that argument does<br />

not help bridge the gulf between <strong>in</strong>tuitive and rational th<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g, because the hard l<strong>in</strong>e<br />

reductionist would only see the mach<strong>in</strong>e and not the ghost.<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>in</strong>teraction between soma and psyche, body and soul-spirit, requires that<br />

we build a bridge between several methods of understand<strong>in</strong>g. Of course if you deny<br />

the reality of what I am call<strong>in</strong>g here the soul-spirit dimension, explanations are much<br />

easier but, I would suggest, therefore also partial. Accord<strong>in</strong>g to Noam Chomsky, there<br />

is still a huge gap between current understand<strong>in</strong>g of the bra<strong>in</strong> and the mental aspects of<br />

the world for which the bra<strong>in</strong> sciences are try<strong>in</strong>g to account. His view is that the m<strong>in</strong>dbody<br />

problem exists only because we have no coherent view of body. As he put it <strong>in</strong> a<br />

recent <strong>in</strong>terview, 4 the problem is that many contemporary th<strong>in</strong>kers have still not really<br />

understood the significance of Newton’s discovery of gravity: “<strong>The</strong> possibility of affect<strong>in</strong>g<br />

objects without touch<strong>in</strong>g them just exploded physicalism and materialism. It has been<br />

common <strong>in</strong> recent years to ridicule Descartes’ ‘ghost <strong>in</strong> the mach<strong>in</strong>e’ <strong>in</strong> postulat<strong>in</strong>g m<strong>in</strong>d<br />

as dist<strong>in</strong>ct from body. Well, Newton came along and he did not exorcise the ghost <strong>in</strong> the<br />

mach<strong>in</strong>e: he exorcised the mach<strong>in</strong>e and left the ghost <strong>in</strong>tact. So now the ghost is there<br />

and the mach<strong>in</strong>e isn’t there. And the m<strong>in</strong>d has mystical properties.”<br />

<strong>The</strong> bone I have to pick with current scientific th<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g is that it precludes the<br />

option that the m<strong>in</strong>d or soul-spiritual part of the human be<strong>in</strong>g can and should be taken<br />

<strong>in</strong>to account. It washes its hands of the real issues and stubbornly turns a bl<strong>in</strong>d eye to half<br />

of life by reduc<strong>in</strong>g everyth<strong>in</strong>g ultimately to bl<strong>in</strong>d mechanical forces. I seek to challenge<br />

current anthropology to get out of its materialistic Catch-22 and th<strong>in</strong>k contextually and<br />

imag<strong>in</strong>atively about the <strong>in</strong>teraction of causes and effects, the mutual feedback of such<br />

processes and the <strong>in</strong>fluence of progressive self determ<strong>in</strong>ation <strong>in</strong> both evolution and<br />

development. In short I ask that it take the reality of the mental or soul-spiritual side of<br />

human nature (what else is the m<strong>in</strong>d, if not a soul-spiritual pr<strong>in</strong>ciple?), as existent <strong>in</strong> its<br />

own right and not merely as a product of physical forces.<br />

_________________________<br />

3<br />

I take this metaphor from an essay by Rudolf Ste<strong>in</strong>er, “Über die Bildnatur des Menschen,” <strong>in</strong><br />

Anthroposophische Leitsätze, May 18, 1924.<br />

4<br />

Guardian Education, Tuesday, April 18, 2000.<br />

16

<strong>Spirit</strong>ual Science<br />

Ste<strong>in</strong>er called his approach spiritual science, but not all who follow his path take<br />

the scientific part as seriously as they should. I also challenge anthroposophists, that is<br />

those who follow and work with ideas of Rudolf Ste<strong>in</strong>er, to break out of the <strong>in</strong>trospection<br />

of Ste<strong>in</strong>er exegesis and take note of the significance of the highly diverse approaches<br />

and data that modern science provides. What Ste<strong>in</strong>er left as his greatest legacy were a<br />

methodology and a practical theory of knowledge. This, rather than the results of his<br />

research, is essentially what we have to work with.<br />

<strong>The</strong> results of his spiritual research exemplify the methodology and are most<br />

usefully taken as such. It is the <strong>in</strong>dividualized application of Ste<strong>in</strong>er’s methodology that<br />

is the real challenge. To attempt to construct a body of knowledge out of such fragments<br />

<strong>in</strong>volves the k<strong>in</strong>d of mentality best suited to archivists and <strong>in</strong>terpreters.<br />

<strong>The</strong> largest (and without doubt valuable) part of anthroposophical secondary<br />

literature consists of compilations and analysis of what Ste<strong>in</strong>er said on this or that topic.<br />

I myself have also contributed to this body of work <strong>in</strong> the field of education. In recent<br />

years I have attempted to relate Ste<strong>in</strong>er’s approach to the discoveries of contemporary<br />

science. 5 I have tried to do so critically and not merely <strong>in</strong> an attempt to justify Ste<strong>in</strong>er by<br />

highlight<strong>in</strong>g the ways <strong>in</strong> which science has tended to confirm the views he expressed.<br />

This book is an elaboration of this process.<br />

One of the difficulties we have to overcome when we take an anthroposophical<br />

perspective is to avoid the wrong k<strong>in</strong>d of anthropomorphism. This is a great temptation<br />

when deal<strong>in</strong>g with concepts such “man as symphony of the creative Logos” or the<br />

human be<strong>in</strong>g as prototype for the animal k<strong>in</strong>gdom. When we live with the metaphor of<br />

the animal k<strong>in</strong>gdom like a fan spread out, each species represent<strong>in</strong>g a different facet and<br />

the human be<strong>in</strong>g as the whole fan, how do we actually imag<strong>in</strong>e this? Does this mean<br />

that the human be<strong>in</strong>g is the end or summit of biological evolution? When Ste<strong>in</strong>er spoke<br />

of Atlanteans and Lemurians as earlier stages <strong>in</strong> human evolution, what did he imag<strong>in</strong>e<br />

archaeologists and paleoanthropologists would f<strong>in</strong>d? Unfortunately it is too easy to<br />

merely assume Ste<strong>in</strong>er must have (somehow) been right, and that poor old scientists<br />

simply don’t get it! I have stumbled across this attitude frequently when giv<strong>in</strong>g lectures<br />

on the subject of this book. Even some anthroposophical publishers have made much<br />

the same po<strong>in</strong>t.<br />

Sadly that is the k<strong>in</strong>d of response that gives anthroposophy a bad name. I am also<br />

fairly certa<strong>in</strong>, given Ste<strong>in</strong>er’s deep respect for the scientific approach, that he would have<br />

found such attitudes disappo<strong>in</strong>t<strong>in</strong>g. He was, after all, a university tra<strong>in</strong>ed scientist. We<br />

are called upon to apply both <strong>in</strong>tuitive and rational, analytical faculties to understand<strong>in</strong>g<br />

our place <strong>in</strong> nature, past and present. As Ste<strong>in</strong>er himself put it,<br />

<strong>Spirit</strong>ual science can only base itself on what the developed soul faculties can<br />

discover <strong>in</strong> the form of imag<strong>in</strong>ations and <strong>in</strong>spirations. <strong>Spirit</strong>ual science can only<br />

speak out of what is consciously experienced <strong>in</strong> the soul. In relation to what outer<br />

science can reveal of nature, spiritual science can more or less only exam<strong>in</strong>e the<br />

spiritual part of evolutionary development. 6<br />

_________________________<br />

5<br />

I have essentially done this <strong>in</strong> a series of articles on language development, memory and the<br />

learn<strong>in</strong>g processes, mostly published <strong>in</strong> the journal Paideia.<br />

6<br />

Ste<strong>in</strong>er, R., lecture of May 22, 1921.<br />

17

<strong>The</strong> dist<strong>in</strong>ction is important. For an understand<strong>in</strong>g of the physical, material side<br />

of nature, Ste<strong>in</strong>er was as dependent on his senses as anyone else, to say noth<strong>in</strong>g of the<br />

scientific research of others. Ste<strong>in</strong>er’s own works show what an avid reader of current<br />

science he was.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Challenge<br />

This book attempts to <strong>in</strong>terpret the story of human evolution as described by<br />

modern anthropology <strong>in</strong> the light of the <strong>in</strong>sights provided by Ste<strong>in</strong>er’s anthroposophy,<br />

which he termed a modern science of the spirit. It seeks to add the factor of spiritual<br />

development to all the other factors that the study of human evolution already takes <strong>in</strong>to<br />

account. In so do<strong>in</strong>g I hope to make a contribution towards the <strong>in</strong>tegration of the spiritual<br />

dimension <strong>in</strong>to the picture of the human be<strong>in</strong>g that currently <strong>in</strong>forms the biological and<br />

anthropological sciences.<br />

As a teacher I have a stubborn and urgent need to know where we stand. <strong>The</strong><br />

motivation for writ<strong>in</strong>g this book has come down to just this: an attempt to clear my<br />

own m<strong>in</strong>d <strong>in</strong> a way that might be helpful to others. I hope it provokes others far more<br />

competent than I am to say, “Hang on there, that’s exactly where you go wrong and here<br />

are the reasons.” To simply oversee, overhear, or ignore the argument for tak<strong>in</strong>g the spirit<br />

<strong>in</strong>to account would be negligent. This may not be the best possible case for reconsider<strong>in</strong>g,<br />

but it is a case that needs answer<strong>in</strong>g. Noth<strong>in</strong>g would please me more than if a respected<br />

professional <strong>in</strong> the field took my thesis apart and, perhaps like a good teacher, po<strong>in</strong>ted<br />

out just where I went wrong.<br />

I do not expect professional anthropologists to learn much from this book <strong>in</strong><br />

the way of new facts. I have sought to <strong>in</strong>terpret the facts and hypotheses current <strong>in</strong> the<br />

paleoanthropological discipl<strong>in</strong>es from the po<strong>in</strong>t of view of the spiritual development<br />

of humank<strong>in</strong>d. I th<strong>in</strong>k I can assure the non-expert that the facts I present have, to the<br />

best of my knowledge, a sound basis. <strong>The</strong> many years of research that went <strong>in</strong>to the<br />

background of this book have left me with the greatest respect for all the discipl<strong>in</strong>es that<br />

contribute to the modern science of human evolution. I cannot claim to comprehend <strong>in</strong><br />

detail the wealth of data from this multi-discipl<strong>in</strong>ary field, let alone at how it is arrived.<br />

As a teacher, however, I cont<strong>in</strong>uously have to seek out the essence of the message each<br />

scientific branch and each author is present<strong>in</strong>g.<br />

In my experience, however, one essential aspect is cont<strong>in</strong>uously overlooked, even<br />

systematically removed, from the agenda. <strong>The</strong>re is one factor that up till now could not<br />

be taken <strong>in</strong>to account. Which graduate student could have gone to his or her professor<br />

with a proposal for a doctoral thesis tak<strong>in</strong>g account of the human spirit <strong>in</strong> evolution?<br />

Well, perhaps at the University of Avalon <strong>in</strong> Glastonbury! It is hard to imag<strong>in</strong>e Dr. Chris<br />

Str<strong>in</strong>ger publish<strong>in</strong>g a paper <strong>in</strong> Nature on “<strong>The</strong> gesture of the human spirit <strong>in</strong> hom<strong>in</strong>id<br />

fossils: a survey,” or Professor Tim White “<strong>Spirit</strong>ual implications of Pliocene hom<strong>in</strong>id<br />

postcranial rema<strong>in</strong>s from Awash, Ethiopia” <strong>in</strong> Current Anthropology! This would not be<br />

quite as bad as “Shelley from the Molecular Po<strong>in</strong>t of View” but, <strong>in</strong> the present academic<br />

scientific world, equally impossible. Is it a form of <strong>in</strong>tellectual apartheid that prevents<br />

ma<strong>in</strong>stream scientists from referr<strong>in</strong>g to such work as, for example, Professor Wolfgang<br />

Schad’s (equally scientific and referenced paper) “Gestalt forms <strong>in</strong> Hom<strong>in</strong>id Fossils” <strong>in</strong><br />

Volume 4 of the journal Goetheanistische Naturwissenschaft? Nor is Schad alone. <strong>The</strong>re is<br />

a whole group of researchers who pursue “contextual biology” and others who apply<br />

similar methods to psychology, medic<strong>in</strong>e, pedagogy, cultural history and other fields of<br />

knowledge.<br />

18

And yet the passion that characterizes much of the science of anthropology<br />

betrays the fact that many lead<strong>in</strong>g workers <strong>in</strong> this field are not unaware of the spiritual<br />

dimension implicit <strong>in</strong> their work. <strong>The</strong>ir language often reveals it, not so much <strong>in</strong> their<br />

academic papers but when they come to present<strong>in</strong>g the broader picture <strong>in</strong> books written<br />

for a general readership. Nor is this, I believe, merely rhetoric and metaphor. <strong>The</strong> problem<br />

is, we lack the language and the precision of concepts to articulate such experiences. We<br />

fall back on metaphor rather than exact term<strong>in</strong>ology. <strong>The</strong> results often sound awkward<br />

and even pretentious when authors try to refer to the imponderables of life. But science,<br />

<strong>in</strong> common with art and the quest for the spiritual, has its true roots <strong>in</strong> awe, wonder and<br />

reverence.<br />

Wonder is an experience we have when we seek or recognize higher mean<strong>in</strong>g.<br />

Here and there we catch glimpses from beh<strong>in</strong>d the scenes of the unfold<strong>in</strong>g public<br />

drama that the scientific search for human orig<strong>in</strong>s has become, which reveal that some<br />

of these scientists acknowledge that the materialistic paradigm is not absolute. Richard<br />

Leakey and Roger Lew<strong>in</strong> admitted <strong>in</strong> their book Orig<strong>in</strong>s Reconsidered how deeply<br />

personal the search for human orig<strong>in</strong>s is. Perhaps more than other scientific discipl<strong>in</strong>es<br />

paleoanthropology is, as they put it, “<strong>in</strong> a sense extra-scientific, more philosophical<br />

and metaphysical, and it addresses questions that arise from our need to understand<br />

the nature of humanity and our place <strong>in</strong> the world.” 7 Nor is this confession from two<br />

<strong>in</strong>fluential scientists <strong>in</strong> the field unique. 8 Let me add the voice of Dr. Donald Johanson,<br />

discoverer of the famous hom<strong>in</strong>id fossil “Lucy” and President of the <strong>Institute</strong> of <strong>Human</strong><br />

Orig<strong>in</strong>s <strong>in</strong> Berkeley, California. In the epilogue of his book Lucy’s Child, Johanson declares,<br />

Any effort to get the truth out about who we really are and where we fit <strong>in</strong>to<br />

the rhythms of the earth seems to me passionately worthwhile. I would like to<br />

th<strong>in</strong>k that my vocation, the search for our orig<strong>in</strong>s, is a part of that truth-quest.<br />

Our shared curiosity about our beg<strong>in</strong>n<strong>in</strong>gs is the emanation of a deeper urge,<br />

felt as wonder, to discover the true humanity that lies beneath and beyond the<br />

old deceptions, the outmoded beliefs. 9<br />

In fact this tone of reverence and respect for the nature of the human be<strong>in</strong>g and our<br />

ancestors can be perceived <strong>in</strong> many such books. I am not sure how all those respected<br />

scientists would expla<strong>in</strong> it. My guess is that most of them would expla<strong>in</strong> it away.<br />

<strong>The</strong> central theme is to ask, Is there mean<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> human development and human<br />

evolution? If so, what is it and how can this be established? All the other questions that<br />

the book addresses relate back to these.<br />

I do not pretend that this book will lead to a paradigm shift but I do expect a<br />

serious refutal. I try to present <strong>in</strong> what follows the case for recognition of the spirit as a<br />

factor <strong>in</strong> evolution. <strong>The</strong> reader will have to judge for himself or herself whether I have<br />

<strong>in</strong> any part succeeded.<br />

_________________________<br />

7<br />

Leakey, R. and R. Lew<strong>in</strong>, 1992, XVI prologue.<br />

8<br />

I quote several with<strong>in</strong> the text. <strong>The</strong>ir articles will be listed <strong>in</strong> the Bibliography. I would simply<br />

like to name Andreas Suchantke, Craig Holdrege, Dr. Ernst-Michael Kranich, Jochen Bockelmühl,<br />

Professor Brian Goodw<strong>in</strong>, Friedrich Kipp, Arm<strong>in</strong> Husemann, M.D., and Jos Verhulst.<br />

9<br />

Johanson, D. and J. Shreeve, 1989, p290.<br />

19

Chapter 1<br />

Self-Knowledge, Truth and Goodness<br />

Discover<strong>in</strong>g where we came from reveals much about who we are, and know<strong>in</strong>g<br />

ourselves helps us understand our orig<strong>in</strong>s. As creative be<strong>in</strong>gs we are always <strong>in</strong> a state of<br />

becom<strong>in</strong>g, which is why evolution and <strong>in</strong>dividual development are aspects of a s<strong>in</strong>gle<br />

dynamic process. <strong>The</strong> questions of human orig<strong>in</strong>s and the nature of the human be<strong>in</strong>g are<br />

<strong>in</strong>extricably woven together. How mank<strong>in</strong>d came to be the dom<strong>in</strong>ant species on earth<br />

is a story that tells us what k<strong>in</strong>d of be<strong>in</strong>gs we are. Conversely, understand<strong>in</strong>g what k<strong>in</strong>d<br />

of be<strong>in</strong>gs we are sheds light on how we have come to our unique position with<strong>in</strong> the<br />

ecology of the earth.<br />

Furthermore, the self-knowledge we ga<strong>in</strong> through study<strong>in</strong>g our orig<strong>in</strong>s is not<br />

merely of personal <strong>in</strong>terest but also has a significance for the rest of world. <strong>The</strong> fact is,<br />

the dest<strong>in</strong>y of life on earth is bound up with this human quest for self knowledge. <strong>The</strong><br />

unique and wondrous abilities of human be<strong>in</strong>gs and how they arose are the subject of<br />

this book, and I will be explor<strong>in</strong>g them <strong>in</strong> detail. But let it be said at the outset that we<br />

have a duty to attempt to understand these faculties <strong>in</strong> as comprehensive and honest<br />

a way we can because of the shadows they cast on the world that susta<strong>in</strong>s us. We<br />

experience this darkness most drastically <strong>in</strong> the ecological consequences of modern<br />

technology which is, after all, the most potent expression of human <strong>in</strong>telligence. So<br />

significant are the consequences of this <strong>in</strong>telligence for the planet that they can hardly<br />

be exaggerated. Let it suffice to list a few of the most familiar (though far from fully<br />

understood) concerns: chemical and radioactive pollution, advanced destruction of the<br />

ozone layer, global warm<strong>in</strong>g, the loss of natural habitats with local and global impact,<br />

dim<strong>in</strong>ish<strong>in</strong>g biodiversity, and human overpopulation. Furthermore, we must add to<br />

our ecological deficits a heavy balance of <strong>in</strong>tra-personal, social, cultural, economic and<br />

political helplessness, of fear and uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty which comes to expression <strong>in</strong> all manner<br />

of social woes.<br />

Whatever we hold to be the significance of the end of one millennium and the<br />

start of another, we have reason enough to reflect on what humanity has become and<br />

what it may become. <strong>The</strong> past century closed with a deep frown of concern on its brow.<br />

A century of <strong>in</strong>credible progress, the most rapid period of fundamental change <strong>in</strong> the<br />

whole of human history, leaves us dangl<strong>in</strong>g, disoriented, faced by paradox where- ever<br />

we turn. Let us be honest and admit to a primal uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty. Who really knows what it all<br />

means? I could fill this chapter with a frighten<strong>in</strong>g story of seem<strong>in</strong>gly <strong>in</strong>tractable problems<br />

and impossible challenges, <strong>in</strong>terpreted by a Babel of compet<strong>in</strong>g theories and therapies.<br />

It is no wonder that we are so drawn to tales of the weird and mysterious on the one<br />

hand and prone to gett<strong>in</strong>g away from it all (self-gratification, endless enterta<strong>in</strong>ment,<br />

consum<strong>in</strong>g, drugs, alcohol and anyth<strong>in</strong>g else that seems to take the pa<strong>in</strong> away) on the<br />

other. It is unnecessary to attempt a scholarly analysis of the symptoms of the times and<br />

21

the challenges they pose for us. One need only leaf through a Sunday newspaper (all ten<br />

sections plus travel supplement) to see not only the crises of the week but the tragedy<br />

of our times. Of course there are shafts of redemptive light pierc<strong>in</strong>g the gloom, but they<br />

only serve to re<strong>in</strong>force the darkness and rem<strong>in</strong>d us that the search for mean<strong>in</strong>g is, as it<br />

always has been, existential.<br />

All these problems flow causally from human activity driven by the human<br />

will, motivated and conceived by the human m<strong>in</strong>d. Presumably this has been the case<br />

for a very long time. I take the view that our history of ecologically harmful behavior<br />

goes back a long way. Just how long is a topic I will be discuss<strong>in</strong>g later. <strong>The</strong> difference,<br />

of course, is that we now possess the means to translate our th<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>to deeds that<br />

are <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itely more powerful than ever before and therefore the stakes are that much<br />

higher. <strong>The</strong> fact is, modern, materialistic, reductionist th<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g (some would add the<br />

epithets, predom<strong>in</strong>antly white, male and Western to the damn<strong>in</strong>g list) has compounded<br />

the morally shallow, greedy, exploitative and destructive side of human behavior and<br />

that even our recently acquired ecological conscience has done little to change <strong>in</strong> terms<br />

of practical consequences.<br />

<strong>The</strong> balance on the other side is noble; the best achievements of modern medic<strong>in</strong>e,<br />

as well as the many technological advances that make life safer, more comfortable, that<br />

give us so much more mobility, access to <strong>in</strong>formation and so on, cannot be glossed over<br />

by doom-laden backward look<strong>in</strong>g pessimism. I owe the life of one of my children to<br />

medical skills that were not available <strong>in</strong> my childhood. That there is (and has been) much<br />

good <strong>in</strong> the world is the po<strong>in</strong>t we need to dwell on because that good is not just there<br />

by chance or because <strong>in</strong> a random scatter of behaviors, some are bound from various<br />

perspectives to be perceived as good. No, they are good by <strong>in</strong>tention, not by chance or<br />

self-<strong>in</strong>terested calculation. Nor does the good arise as an accumulative aggregate of bl<strong>in</strong>d<br />

progress, along the pr<strong>in</strong>ciple that the process of trial and error will result <strong>in</strong> some good<br />

because good is what works. <strong>The</strong> fact that there is good <strong>in</strong> the world, that good th<strong>in</strong>gs<br />

happen, that good th<strong>in</strong>gs are discovered (and sometimes rediscovered), is crucial to our<br />

understand<strong>in</strong>g of ourselves because goodness, its presence and absence, implies that<br />

there is mean<strong>in</strong>g.<br />

This assertion may strike the reader as hopelessly naïve or as well <strong>in</strong>tentioned, if<br />

deluded piety. I hope I can show that it is neither. As I shall try to argue, a human be<strong>in</strong>g<br />

is capable of do<strong>in</strong>g the good th<strong>in</strong>g out of <strong>in</strong>sight and free will. No one can deny that a<br />

human be<strong>in</strong>g can do evil, often <strong>in</strong>advertently but also <strong>in</strong>tentionally. It would be foolish<br />

to claim otherwise. Yet what makes the deeds of human be<strong>in</strong>gs either good or bad is not<br />

absolute but relative. But, relative does not mean random. Th<strong>in</strong>gs or events of themselves<br />

do not have mean<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> the abstract, but only <strong>in</strong> context. It is the same with goodness.<br />

Goodness is always <strong>in</strong> context. Evil, its antithesis, which comes <strong>in</strong> all shades, is always <strong>in</strong><br />

some way out of context. One could also say out of balance. What makes the difference<br />

is mean<strong>in</strong>g.<br />

<strong>The</strong> search for mean<strong>in</strong>g is <strong>in</strong>tr<strong>in</strong>sic to the process of knowledge. But for<br />

knowledge to have mean<strong>in</strong>g it must be as complete as possible, which is to say it must<br />

be contextual, it must be embedded <strong>in</strong> a context. <strong>The</strong> context gives the knowledge its<br />

mean<strong>in</strong>g. <strong>The</strong> greater the context, the greater the knowledge and its mean<strong>in</strong>g.<br />

Ways of Know<strong>in</strong>g<br />

<strong>The</strong>re are different ways of know<strong>in</strong>g th<strong>in</strong>gs. We can know about th<strong>in</strong>gs. This<br />

preposition implies a circl<strong>in</strong>g at a certa<strong>in</strong> distance from the po<strong>in</strong>t. This makes a spatial<br />

22

dist<strong>in</strong>ction between knower and known, what we call <strong>in</strong> grammatical terms, subject and<br />

object. <strong>The</strong> predicate describes what we do to the object. This k<strong>in</strong>d of knowledge always<br />

means do<strong>in</strong>g someth<strong>in</strong>g to or with the object of our knowledge. We can also, however,<br />

know someth<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> the sense “I know her,” which is different from “I know about her.”<br />

<strong>The</strong> difference is one of <strong>in</strong>timacy. <strong>The</strong> Biblical phrase, “Abraham knew Sarah,” makes the<br />

<strong>in</strong>timacy clearer. This second know<strong>in</strong>g implies that we unite ourselves with the object,<br />

or at least <strong>in</strong>tend to approach as closely as we can. Both k<strong>in</strong>ds of know<strong>in</strong>g are stages <strong>in</strong><br />

the act of know<strong>in</strong>g. If the th<strong>in</strong>gs we know about rema<strong>in</strong> th<strong>in</strong>gs, we rema<strong>in</strong> detached, our<br />

sense of responsibility is dim<strong>in</strong>ished, because the mean<strong>in</strong>g of the th<strong>in</strong>g we know about<br />

is <strong>in</strong>significant <strong>in</strong> relation to the totality of its liv<strong>in</strong>g context. When we know someth<strong>in</strong>g<br />

more <strong>in</strong>timately, when we recognize the other as be<strong>in</strong>g, we enter <strong>in</strong>to dialogue with it.<br />

It is a two-way process. In dialogue we give, perhaps even risk, someth<strong>in</strong>g of ourselves;<br />

otherwise it is no true dialogue.<br />

<strong>The</strong> problem arises when our method of know<strong>in</strong>g stops at the “know<strong>in</strong>g about”<br />

stage. This is especially so when our object is the human be<strong>in</strong>g, humanity <strong>in</strong> general, or<br />

simply ourselves, though the tendency is equally true of other objects. If our method<br />

of know<strong>in</strong>g about the human be<strong>in</strong>g filters out aspects of human nature, if we focus on<br />

the parts and ignore, or fail to recognize the other parts, we cannot know the whole, or<br />

even approach it. To be blunt, if we treat the human be<strong>in</strong>g only as a mechanism, however<br />

complex, as a gene mach<strong>in</strong>e, as a collective of biochemical systems, we overlook the<br />

human as be<strong>in</strong>g. This is the ma<strong>in</strong> problem with the materialistic reductionist approach.<br />

It is true whenever this method is exclusively applied to the liv<strong>in</strong>g world as a whole.<br />

Firstly it denies the fundamental quality of be<strong>in</strong>g to liv<strong>in</strong>g organisms or processes, s<strong>in</strong>ce<br />

be<strong>in</strong>g makes no sense to a materialistic po<strong>in</strong>t of view, and secondly, its methods only<br />

allow us to know about th<strong>in</strong>gs.<br />

To some extent this is understandable. It is difficult to take the whole context <strong>in</strong>to<br />

account, it is much easier to start with parts. In focus<strong>in</strong>g on one po<strong>in</strong>t, <strong>in</strong> try<strong>in</strong>g to p<strong>in</strong> it<br />

down, other po<strong>in</strong>ts of reference recede and go out of focus. <strong>The</strong> object becomes dislocated<br />

or displaced from its context, from the ordered whole with which we started.<br />

Each attempt to ga<strong>in</strong> clarity sooner or later fails. Th<strong>in</strong>gs lose their mean<strong>in</strong>g when<br />

they lose their context. Faced with complexity (Is there anyth<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> the liv<strong>in</strong>g world<br />

that is not complex?) the scientist seeks to simplify, remove as many factors as possible,<br />

except what they consider to be the essential, and establish norms for comparison. With<br />

each attempt to establish norms, general structures or predictable patterns (which we<br />

hope will provide us with security), we permanently risk distort<strong>in</strong>g or los<strong>in</strong>g the very<br />

phenomena be<strong>in</strong>g studied. Why? Because each case on closer exam<strong>in</strong>ation turns out to<br />

be different, to vary from the norm <strong>in</strong> ways which make generalization a largely fruitless<br />

and often semantic task. Thus the phenomenon may have to be altered so that we can<br />

deal with it. This is very obvious <strong>in</strong> the whole field of the sciences that try to understand<br />

the human be<strong>in</strong>g. <strong>The</strong> complexity we discover threatens to overwhelm the means we<br />