Download - IMPACT Magazine Online!

Download - IMPACT Magazine Online!

Download - IMPACT Magazine Online!

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

COVER<br />

STORY<br />

intergovernmental agencies and leading international human<br />

rights, church, labor, migrant and women’s organizations.<br />

The Steering Committee’s activities at international and national<br />

levels in order to publicize and raise awareness of the<br />

Convention through the Global Campaign led to a salutary<br />

increase in the number of ratifications and signatures.<br />

It is worth nothing that the 29 States parties are principally<br />

sending States, although<br />

some of them are also transit<br />

and receiving States. None of<br />

the major receiving States has<br />

ratified the Convention. When<br />

we consider the geographical<br />

distribution of the States parties,<br />

we note that 12 are from Africa,<br />

9 from Latin America and the<br />

Caribbean, 7 from Asia, and 1<br />

from Central and Eastern Europe.<br />

Another 15 States have signed but<br />

not ratified the Convention. As of<br />

May 2005, no Western State has<br />

signed or ratified the Convention,<br />

although some of them were<br />

actively involved in the Convention’s<br />

drafting process.<br />

Obstacles to Ratification<br />

This brings us to the question of the possible obstacles<br />

to ratification. How is it that the Convention has met with<br />

so little enthusiasm by States, including those States who<br />

are usually quick to champion human rights? UNESCO has<br />

carried out several interesting studies on this matter.<br />

Firstly, it is obvious that the contents of one or other<br />

provision may be unacceptable to some States, for instance<br />

because it would give rights that would go beyond its capacities.<br />

Fortunately, the Convention itself has foreseen<br />

the possibility of entering reservations to the application<br />

of certain articles. This obstacle is therefore one that can<br />

be overcome by a careful study of the compatibility of the<br />

domestic legislation with the rights contained in the Convention,<br />

and the drafting of pertinent<br />

reservations.<br />

Secondly, the Convention has<br />

given rise to many misconceptions.<br />

One of the common misconceptions<br />

is the often expressed opinion<br />

that the Convention favors irregular<br />

migration. It is clear from the<br />

text of the Convention that it does<br />

not and that, on the contrary, the<br />

concept of giving rights to irregular<br />

migrant workers was inspired<br />

not only by the basic principle of<br />

respect for the dignity of all human<br />

beings, but also by the desire to<br />

discourage recourse by employers<br />

to irregular labor by making it<br />

much less advantageous, as unequivocally expressed in the<br />

preamble of the Convention.<br />

Thirdly, many countries fear the high cost of developing<br />

an infrastructure for the implementation of the Convention.<br />

The Convention is a long and complex instrument that provides<br />

many rights in different fields, and the implementation<br />

thereof consequently involves many government departments,<br />

coordination of which may not be an easy task. It<br />

is illustrative in this respect that none of the States parties<br />

© ishamaec.wordpress.com<br />

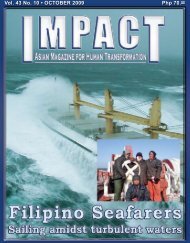

By Fr. Edwin Corros, CS<br />

Joven de la Cruz (not his real name)<br />

was a former overseas Filipino<br />

worker (OFW) from Antipolo, Rizal.<br />

He has sought the assistance of the<br />

Episcopal Commission on Migrants and<br />

Itinerant People (ECMI), complaining<br />

of harassment from the lending agency<br />

that paid his placement fee to get a job<br />

in Taiwan as a factory worker. He was<br />

repatriated when the factory where he<br />

was employed temporarily cut down its<br />

operations due to lesser demand of IT<br />

products in United States and Europe<br />

because of global economic recession.<br />

Afraid of being jailed for not paying his<br />

debts, he sought ECMI’s help.<br />

When he arrived in Taiwan in March<br />

2008, De la Cruz did not find anything<br />

unusual about his employment. Three<br />

months later, his employer announced<br />

that the factory will operate only thrice<br />

a week. This meant that Joven and<br />

other foreign migrant workers would<br />

only work three days weekly, hence, will<br />

also receive a salary that was equivalent<br />

to the three-day job. The company’s<br />

management had explained that it could<br />

not afford to pay all the workers due<br />

to the low demand of their company’s<br />

product. With his salary cut into almost<br />

half of his initial monthly wage, Joven<br />

had to face the consequence of being<br />

unable to pay his debts arising from the<br />

placement fee he had borrowed in the<br />

Philippines. Added to this burden, the<br />

workers also had to pay their board and<br />

lodging on days they were not working.<br />

This unexpected turn of events came as<br />

a big blow to Joven and his co-workers.<br />

All they could do was to wait for their<br />

condition to improve.<br />

Few weeks later, the company offered<br />

the migrant workers the possibility<br />

of repatriation with a free airline ticket.<br />

Realizing that he had just been working<br />

without saving, plus the fact that<br />

his salary was not enough to pay his<br />

debts, Joven had immediately accepted<br />

the offer. Before leaving Taiwan he was<br />

asked to sign a document implying he<br />

had resigned from work. Although he<br />

was not sure of the consequence of<br />

such decision, he decided to sign the<br />

document because he did not have<br />

the chance to seek help from the<br />

Manila Economic and Cultural Office<br />

(MECO) in Taipei, the Philippines de<br />

facto embassy.<br />

A month after his arrival in the country,<br />

Joven started receiving a statement<br />

of account from the lending company<br />

that paid his placement fee for Taiwan.<br />

He called up the lending company explaining<br />

why he was not able to pay his<br />

debt. Unfortunately, after explaining his<br />

incapacity to pay, he received a stronger<br />

letter demanding that he pay his debts<br />

including accumulated interests and<br />

surcharges or else he will be brought to<br />

court. It was this threat of being jailed<br />

that brought Joven to seek ECMI’s help<br />

through the Antipolo Diocesan Commission<br />

for Migrants.<br />

The case of Joven is a usual<br />

example how some overseas Filipino<br />

20<br />

<strong>IMPACT</strong> • February 2010