You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Nex t <strong>Stage</strong> Resource Guide<br />

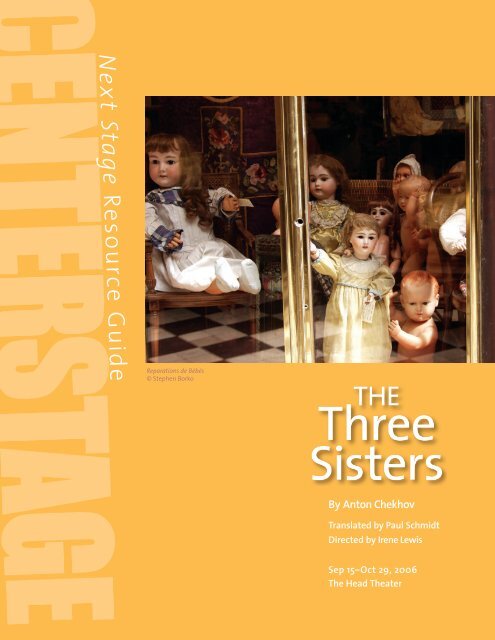

Reparations de Bébés<br />

© Stephen Borko<br />

<strong>By</strong> <strong>Anton</strong> <strong>Chekhov</strong><br />

Translated by Paul Schmidt<br />

Directed by Irene Lewis<br />

Sep 15–Oct 29, 2006<br />

The Head Theater

Irene Lewis Artistic Director<br />

Michael Ross Managing Director<br />

Contents<br />

Setting the <strong>Stage</strong> 2<br />

Cast/Director’s Note 3<br />

<strong>Chekhov</strong> 4<br />

Writing with Light 5<br />

Snapshots Out of Time 10<br />

“Love” Letters 13<br />

Glossary 14<br />

Annotated Bibliography 18<br />

The Next <strong>Stage</strong> Resource Guide<br />

is published by: CENTERSTAGE Associates<br />

700 North Calvert Street<br />

Baltimore, Maryland 21202<br />

Editor Aaron Heinsman<br />

Contributors Dina Epshteyn, Kathryn Leiby, Irene<br />

Lewis, Steve Lichtenstein, Gavin Witt<br />

Art Direction/Design Bill Geenen<br />

Design Jason Gembicki<br />

Government Support<br />

Anne Arundel County Executive and County Council<br />

Baltimore County Commission on Arts and Sciences<br />

Carroll County Government<br />

The City of Baltimore and Baltimore Office of Promotions<br />

& The Arts<br />

Harford County Executive and County Council<br />

Howard County Government and Howard County<br />

Arts Council<br />

Maryland State Arts Council<br />

Corporate Support<br />

CitiFinancial and Citigroup Foundation<br />

Legg Mason<br />

M&T Bank<br />

Procter & Gamble Cosmetics Foundation<br />

Provident Bank<br />

T. Rowe Price Associates Foundation, Inc.<br />

Verizon<br />

Wal-Mart<br />

Washington Gas<br />

Foundation & INDIVIDUAL Support<br />

Anonymous<br />

The Helen P. Denit Charitable Trust<br />

The Goldsmith Family Foundation<br />

Lockhart Vaughan Foundation<br />

The Macht Philanthropic Fund<br />

Jeanne Murphy<br />

The Nellie Mae Education Foundation<br />

The Jim & Patty Rouse Charitable Foundation<br />

The Sheridan Foundation<br />

The Aaron Straus & Lillie Straus Foundation<br />

VSA arts and MetLife Foundation<br />

The Three Sisters<br />

<strong>By</strong> <strong>Anton</strong> <strong>Chekhov</strong><br />

Translated by Paul Schmidt<br />

Irene Lewis Director<br />

Robert Israel Scenic Designer<br />

Candice Donnelly Costume Designer<br />

Mimi Jordan Sherin Lighting Designer<br />

Eric Svejcar Composer/Music Director<br />

David Budries Sound Designer<br />

John Carrafa Choreographer<br />

J. Allen Suddeth Fight Director<br />

Gavin Witt Production Dramaturg<br />

Dina Epshteyn Associate Production Dramaturg<br />

Harriet Bass Casting Director<br />

Sponsored by<br />

CENTERSTAGE operates under an<br />

agreement between LORT and<br />

Actors’ Equity Association, the<br />

union of professional actors and<br />

stage managers in the United<br />

States.<br />

The Director and Choreographer are<br />

members of the Society of <strong>Stage</strong><br />

Directors and Choreographers, Inc.,<br />

an independent national labor union.<br />

The scenic, costume, lighting, and<br />

sound designers in LORT theaters<br />

are represented by United Scenic<br />

Artists, Local USA-829 of the IATSE.<br />

<strong>Center</strong><strong>Stage</strong> is a constituent of Theatre Communications<br />

Group (TCG), the national organization for the nonprofit<br />

professional theater, and is a member of the League of<br />

Resident Theatres (LORT), the national collective bargaining<br />

organization of professional regional theaters.<br />

Presented by special arrangement with Helen Merrill LLC.<br />

The 2006–07 Season is dedicated to Nancy Keen Roche.

Set ting the <strong>Stage</strong><br />

The Three Sisters by <strong>Anton</strong> <strong>Chekhov</strong><br />

by Kathryn Leiby, Community Programs & Education Intern<br />

Characters:<br />

Andrey Sergeiyevitch Prozorov<br />

Natasha Ivanovna—his fiancée, later his wife<br />

Olga, Masha, and Irina—his sisters<br />

Fyodor Ilyitch Kulygin—Masha’s husband, a teacher<br />

Alexander Ignateyevitch Vershinin—lieutenant-colonel<br />

Baron Tuzenbach—lieutenant in the army<br />

Vassily Vassilyevitch Solyony—captain<br />

Ivan Romanovitch Chebutykin—army doctor<br />

Alexei Petrovitch Fedotik—second lieutenant<br />

Vladimir Carlovitch Rohde—second lieutenant<br />

Ferapont—janitor at County Council offices<br />

Anfisa—the Prózorovs’ nurse<br />

Setting:<br />

Act 1: Spring (May 5)<br />

Act 2: Winter—1.5 years later<br />

Act 3: Summer—1.5 years later<br />

Act 4: Fall—3 months later<br />

For the Prozorov family, May 5 th is a day of celebration and sadness. It is Irina Prozorov’s birthday, which<br />

is always a cause of festivity. This year, though, it also marks the one-year anniversary of her father’s<br />

death. Nonetheless, Irina is happy to shed her mourning black for a white party dress. Her sisters, Olga<br />

and Masha, and her brother, Andrey, are doing their best to throw her a party. Guests include officers from<br />

the regiment garrisoned in town; Masha’s husband Kulygin, the local schoolteacher; and Natasha, the local<br />

girl that Andrey’s sweet on. Each member of this eclectic group seems to have a different idea of how the<br />

afternoon’s merriment should proceed; and, even in the joyous atmosphere of good spirits and laughter, the<br />

ties of family and friendship may not be enough to prevail.<br />

Set in a Russian provincial city at the turn of the last century, <strong>Anton</strong> <strong>Chekhov</strong>’s The Three Sisters shows a<br />

family aching for change. <strong>Chekhov</strong> viewed life as a struggle between who we were and who we become.<br />

He showed us a world filled with people who want more than their lives can give them and know that they<br />

may never be able to attain it.<br />

After spending their childhood years in Moscow, the Prozorov siblings moved with their father, a general,<br />

to what seems to them like the ends of the earth. Since the general’s death, the family has done their best<br />

to keep life as he would have wanted it, but have had some bumps on the way. Brother Andrey was to be<br />

a famous scholar, but has begun to let himself go. Olga teaches unhappily at the local girls’ school, Masha<br />

married too young, and Irina hopes that hard work might fill her life with purpose. She is surrounded<br />

by doting military men, from earnest Baron Tuzenbach to rebellious Captain Solyony, from the paternal<br />

Chebutykin to the gentle and inseparable Lieutenants Fedotik and Rohde. When Colonel Vershinin, the<br />

regiment’s new commander, arrives with his tales of the capital, the sisters press endlessly for information,<br />

living vicariously through his stories and continuously dreaming of their return to Moscow. Hope may<br />

blossom brightly, but disappointment looms with it. ●<br />

Next <strong>Stage</strong>: The Three Sisters | 2

The Three Sisters<br />

C ast<br />

(in alphabetical order)<br />

David Adkins* Vershinin<br />

Christine Marie Brown* Masha<br />

Willy Conley Fedotik<br />

Gene Farber* Solyony<br />

Kristin Fiorella* Natasha<br />

Mary Fogarty* Anfisa<br />

Joe Hickey* Kulygin<br />

Mahira Kakkar* Irina<br />

Laurence O’Dwyer* Chebutykin<br />

Andy Paterson* Rohde/Voice of Fedotik<br />

Stacy Ross* Olga<br />

Matt Bradford Sullivan* Tuzenbach<br />

Evan Thompson* Ferapont<br />

Tony Ward* Andrey<br />

Alina Lightchaser Musician/Servant<br />

Bradley Wayne Smith Musician/Servant<br />

Debra Acquavella* <strong>Stage</strong> Manager<br />

Mike Schleifer* Assistant <strong>Stage</strong> Manager<br />

* Member of Actors’ Equity Association<br />

Set ting<br />

Place: The Prozorov’s home in the<br />

Russian Provinces, ca. 1900<br />

Time:<br />

Act I: Spring<br />

Act II: Winter, 18 months later<br />

15-minute intermission<br />

Act III: Summer, 18 months later<br />

Act IV: Autumn, 3 months later<br />

Olga Knipper, 1899. The photograph prompted<br />

<strong>Chekhov</strong> to comment: “There’s a little demon lurking<br />

behind your modest expression of quiet sadness.”<br />

<strong>Chekhov</strong> wrote the<br />

role of Masha in Three<br />

Sisters for Olga Knipper,<br />

then his lover and soon to be his wife. It became<br />

her signature role, so much so that the final words<br />

she spoke onstage, at a benefit for her 90 th birthday,<br />

were lines of Masha’s that she’d made almost<br />

legendary—lines of poetry from Pushkin’s Ruslan<br />

and Ludmilla that Masha repeats throughout the<br />

play. That said, you won’t hear those particular<br />

verses in our production. While millions of Russian<br />

school kids, then and now, might memorize and<br />

recognize those lines, they are alien, not familiar, to<br />

us. Where the author had counted on recognition<br />

from his audience, we’d find only incomprehension.<br />

So much of <strong>Chekhov</strong> is about looking into his plays<br />

and seeing yourself, yet how many of us would hear<br />

that quotation and know its source, or recognize<br />

the subtle evocations of thwarted love suggested<br />

by images of a golden chain and an educated cat?<br />

So instead of making <strong>Chekhov</strong> exotic and<br />

distant, I’m hoping this production will<br />

help make him more immediate and<br />

alive. You’ll hear quotations that you<br />

might recognize. And we can all share<br />

a chuckle that <strong>Chekhov</strong> decided to give<br />

Andrey’s first-born son a name you’d<br />

only give to a dog.<br />

— Irene Lewis, Director<br />

Next <strong>Stage</strong>: The Three Sisters | 3

<strong>Chekhov</strong><br />

1860–1904<br />

<strong>By</strong> Gavin Witt, Production Dramaturg<br />

When <strong>Anton</strong> <strong>Chekhov</strong> was born in the Black expanse of the steppes. The population surged to the cities<br />

Sea backwater of Taganrog, anywhere from<br />

20 to 40 million Russians lived in slavery as<br />

serfs, the legal property of landowners, the<br />

imperial family, or the Church. The czar freed the<br />

serfs by proclamation in 1861, two years before four million<br />

“You ask ‘What is life?’<br />

That is the same as asking<br />

‘What is a carrot?’<br />

A carrot is a carrot and<br />

we know nothing more.”<br />

in search of work. There were conflicts of expansion with<br />

Turkey, Japan, and China; and there continued a diplomatic<br />

and military quadrille of shifting allegiances with the nations<br />

of Europe. There were wild swings from political reform—or<br />

the semblance of reform—to reactionary repression. While an<br />

American slaves gained their freedom. Russia, mired in tradition,<br />

harnessed to a rigidly stratified society, governed by an imperial<br />

autocracy, and entrenched in a centuries-old agricultural<br />

economy, embarked on an all-out effort to industrialize and<br />

compete. Webs of railways were thrown across the infinite<br />

elite of about 100,000 enjoyed a steadily rising standard of<br />

living and all modern luxuries, many of Russia’s 120 million or so<br />

citizens lived in nearly medieval conditions. As for the serfs, they<br />

emerged from slavery into a poverty made even more abject by<br />

the burden of debt. >>><br />

Next <strong>Stage</strong>: The Three Sisters | 4

“Any idiot can face a crisis — it’s day-to-day living that wears you out.”<br />

It was an era of contradictions, juxtapositions,<br />

and astonishing transformation.<br />

Writing with Light<br />

It is noteworthy<br />

that, throughout<br />

The Three Sisters,<br />

Lieutenant Fedotik<br />

is rarely without<br />

his camera.<br />

by Gavin Witt, Production Dramaturg<br />

The shutterbug snapping candids has<br />

become a thoroughly modern figure, yet<br />

it is one with a long provenance. When<br />

<strong>Chekhov</strong> conceived and wrote his play, in<br />

those years around 1900, photography<br />

as a pastime and amateur enjoyment<br />

had exploded. Photography moved in a<br />

mere lifetime from the arcane specialty<br />

of scientists and professionals to the<br />

inescapable clutches of the hobbyists.<br />

Technical advances, cheap access, and<br />

successful marketing made cameras<br />

Next <strong>Stage</strong>: The Three Sisters | 5

“Nothing lulls and inebriates like money; when you have a lot,<br />

the world seems a better place than it actually is.”<br />

>>><br />

<strong>Chekhov</strong>’s lifetime witnessed Russia’s emergence from a<br />

benighted past towards some measure of modernity. Scientific,<br />

cultural, medical, philosophical, literary, musical, technological<br />

progress all battled with stagnation—a deeply conservative<br />

resistance to change of any kind. Railways crisscrossed the<br />

interior, but industrial progress was slow to follow. In addition<br />

to emancipation, there were other gestures of political reform.<br />

But for every step toward moderation and inclusion, harsh<br />

repression would follow—and by 1900 Marx was not the only<br />

one insisting that a specter haunted the monarchies of Europe.<br />

Idealistic calls for a better world, led by the noblesse oblige of<br />

Tolstoy and his circle, merely decorated the surface of a boiling<br />

cauldron of resentment, steeped in poverty and seething with<br />

the threat of imminent revolution—which bubbled over in<br />

violence only a year after <strong>Chekhov</strong>’s death. >>><br />

popular with middle class families from<br />

America to Russia, where everyone from<br />

provincial families to the Grand Duchess<br />

Anastasia quickly became inseparable<br />

from a Kodak Brownie. Today’s incessant<br />

snapping of camera phones is the logical<br />

descendant of the process <strong>Chekhov</strong><br />

wryly records in his play. And so, to<br />

document the many juxtapositions and<br />

wide gulfs of life in <strong>Chekhov</strong>’s Russia, we<br />

have an abundance of photographs—<br />

amateur and professional alike.<br />

The word photography itself—a combination of Greek<br />

words meaning to write with light —appeared around<br />

1839. Written in light. Inscribed with lightning. An apt<br />

name—and an apt image for <strong>Chekhov</strong>’s delicate,<br />

mournful comedy: momentary, revealing,<br />

potentially shattering, and just as ephemeral. ●<br />

Next <strong>Stage</strong>: The Three Sisters | 6

“The only reviewer who ever made an impression on me was Skabichevsky,<br />

who prophesied that I would die drunk in the bottom of a ditch.”<br />

>>><br />

Cultured Russians looked to Germany and France, while the<br />

populace at large clung to folk traditions. Like the imperial<br />

double-headed eagle, Russia looked both East and West at the<br />

same time; a division embodied in another duality of Moscow<br />

and St. Petersburg. Moscow: Russian, “Eastern,” chaotic,<br />

dingy; Petersburg: European, “Western,” tidy, orderly. The<br />

broad bourgeois boulevards of St. Petersburg, thronged with<br />

gladsome gadding gallants, contrasted with the noisome tangle<br />

of Moscow’s winding alleys, narrow lanes, and onion domes.<br />

And the countryside, so placid beneath the brush of the painter<br />

Ilya Repin and so ruthlessly chronicled in <strong>Chekhov</strong>’s short<br />

stories, offered along with its majestic landscapes a panoply<br />

of superstition, corruption, misery, poverty, cruelty, laziness,<br />

incompetence, and ignorance.<br />

Amidst these changes and these oppositions, <strong>Chekhov</strong>’s own<br />

life offered comparable contrasts and, in a mere 44 years,<br />

transformations as remarkable. Regarded by the time of his<br />

death as a master of Russian literature and a pioneer of modern<br />

drama, his funeral attended by tens of thousands, <strong>Chekhov</strong> was<br />

one of six children born to a barely solvent grocer—himself the<br />

son of a former serf—in a town most of the way to nowhere. At<br />

16, <strong>Anton</strong> was left to fend for himself when his father, bankrupt,<br />

took the rest of the family and fled to Moscow. In fact, he had to<br />

fend for the whole family: while finishing school, the teenager<br />

tutored and sold off the family’s meager remaining possessions<br />

in order to send money to his parents and siblings.<br />

<strong>By</strong> 19, having won a scholarship to medical school, <strong>Chekhov</strong><br />

followed the others to Moscow and became the head of his<br />

family. There, he not only gained his degree as a doctor and<br />

started to show the first symptoms of tuberculosis, he also<br />

continued supporting his entire family—making money writing<br />

short, mostly comic, stories for publication. As an enviable<br />

and lucrative writing career took shape, however, <strong>Chekhov</strong><br />

the scientific humanist asserted himself as well. He made a<br />

remarkable voyage of thousands of miles to a prison camp on<br />

the Siberian island of Sakhalin, where he personally interviewed<br />

10,000 prisoners. The results, published, became a rallying cry<br />

for prison reform and established his credentials as a champion<br />

Next <strong>Stage</strong>: The Three Sisters | 7

“We go to great pains to alter life for the happiness of our descendants<br />

and our descendants will say as usual:<br />

things used to be so much better, life today is worse than it used to be.”<br />

of the downtrodden—as did his volunteering as a doctor during<br />

cholera epidemics, famines, and other crises. Yet he also stood<br />

resolutely by his friend and publisher Suvorin, among the most<br />

viciously reactionary men in the land.<br />

With medicine as his wife and writing as his mistress—as he<br />

phrased it—<strong>Chekhov</strong> pursued a punishing schedule. He wrote<br />

incessantly, championed causes, traveled the world, and carried<br />

on multiple affairs with besotted women who pursued him<br />

in vain. At the same time, he was almost misanthropic in his<br />

hunger for solitude; and as his fame and popularity grew, so<br />

did his aversion to being celebrated in any way. He was gentle<br />

and kind to animals, children, or the sick, but was also a coarse<br />

practical jokester—who loved best to laugh at his own expense.<br />

He sought privacy, but bought and built property, the grocer’s<br />

son no more. His intimates were nobility, literary and cultural<br />

leaders, the cream of society; yet he also sought out the needy<br />

and the overlooked, using his medical skill to tend impoverished<br />

peasants for free.<br />

Gradually, comic squibs gave way to more ambivalent and<br />

ambitious stories, and the early vaudeville sketches to fulllength<br />

dramas—unheralded at first, as <strong>Chekhov</strong> struggled to<br />

reconcile, or serve, competing impulses of tone and outlook.<br />

After the disastrous premiere of The Seagull, he even vowed to<br />

give up writing theater entirely. But then came one of those rare<br />

moments of world-changing alchemy and a partnership that<br />

altered everything. The fledgling Moscow Art Theater sought to<br />

spearhead a new approach to theater—to apply new, modern<br />

ideas to create a new drama for a new age. To accompany<br />

their radical new approach to acting and staging they required<br />

new writing to embody their ideals. Mr. Stanislavsky, meet Mr.<br />

<strong>Chekhov</strong>. The theater remounted The Seagull, triumphantly,<br />

and fresh horizons beckoned. <strong>Chekhov</strong>, Stanislavsky, and the<br />

Moscow Art Theater came to be associated inseparably, yet they<br />

were often at odds over the plays, which <strong>Chekhov</strong> insisted be<br />

played as farces while Stanislavsky, he complained, turned them<br />

all into plangent tragedy. >>><br />

Next <strong>Stage</strong>: The Three Sisters | 8

“A writer is not a confectioner, a cosmetic dealer, or an entertainer.<br />

He is a man who has signed a contract<br />

with his conscience and his sense of duty.”<br />

>>><br />

Another partnership that emerged from the association was<br />

<strong>Chekhov</strong>’s relationship with the actress Olga Knipper, for whom<br />

he wrote the role of Masha in The Three Sisters and whom he<br />

finally married. After decades of dalliances and hesitations and<br />

reluctance and furtive affairs, <strong>Chekhov</strong> succumbed to wedded<br />

bliss. Only, of course, to introduce new contradictions by<br />

spending more time away from his wife than with her. No easy<br />

domesticity for this pair, as she remained in Moscow rehearsing<br />

and performing while he sought healthy climates and a cure. It<br />

was a distance both seemed to accept as conveniently imposed.<br />

For haunting each of <strong>Chekhov</strong>’s achievements, perhaps driving<br />

his unflagging efforts, was the terrible, undeniable medical<br />

reality of his consumption. Long before an official diagnosis, long<br />

before he brought himself to admit it or accepted care, <strong>Chekhov</strong><br />

had suffered from an advancing case of tuberculosis that<br />

was increasingly accompanied by a host of other debilitating<br />

ailments, inside and out. Of course, he was sufficiently a man<br />

of science to know his death sentence for precisely what it<br />

was; lest he have any doubts, he had watched his brother die<br />

of the same wasting scourge. But on he forged, only gradually<br />

giving way to the bloody coughs and the urgent need to rest in<br />

a warm, dry climate. So having conquered Moscow artistically,<br />

and immortalized his adopted city in The Three Sisters, he first<br />

retired to the house he built in Yalta, then retreated to a German<br />

spa. It was there, with a final sip of champagne, that he died<br />

in 1904. Ever the centerpiece of odd juxtapositions, ever alive<br />

to the absurd, ever the cynical optimist, ever the most private<br />

of public figures, how <strong>Chekhov</strong> would have loved his final<br />

accidental gestures. Shipped back to Moscow for burial in a<br />

refrigerated train car marked “Oysters,” his coffin was confused<br />

with that of a dead general and the throngs who came to mourn<br />

him followed the wrong cortège.<br />

In his maturity, <strong>Chekhov</strong> was hailed as a standard-bearer of<br />

literary Naturalism—the objective, quasi-scientific observation,<br />

dissection, and recording of human behavior in literature. And<br />

in some ways, so he was. Of course, he always insisted on the<br />

comic, farcical elements of his plays—even, or especially, in<br />

the unexpected and out-of-the-way little accidental gestures<br />

Next <strong>Stage</strong>: The Three Sisters | 9

“Medicine is my lawful wife and literature my mistress;<br />

when I get tired of one, I spend the night with the other.”<br />

everyone else overlooked. His theatrical writing rejected the<br />

careful plotting of the well-made play so in fashion in his<br />

day and rejected even the basic linear structures of classical<br />

theater. He wrote quite proudly of these rejections, in fact.<br />

True to his many contradictions—as writer-doctor, comedianclinician,<br />

reformer-misanthrope, philanderer-misogynist, and<br />

a faithful skeptic—his writing balanced contrasting impulses;<br />

elements of Naturalism could co-exist with aspects of<br />

Symbolism.<br />

Whatever the category, there’s no trouble discerning in<br />

<strong>Chekhov</strong>’s writing the seeds of what would become so much<br />

modern drama, from Ionesco to Beckett, Maeterlinck to Mamet,<br />

O’Neill to Shepard. Freudian subtext, psychological realism,<br />

Absurdism, Existentialism, and more—they are all there.<br />

Nothing happens, or seems to happen. Nothing happens, and<br />

everything happens. Just life, unexpected and incomplete. ●<br />

“Do you know for how many<br />

years I shall be read?”<br />

asked <strong>Chekhov</strong>. “Seven.”<br />

“Why seven?”<br />

asked Ivan Bunin.<br />

“Well,” <strong>Chekhov</strong> answered,<br />

“seven and a half then.”<br />

Above left: <strong>Chekhov</strong>’s birthplace.<br />

Above right: crowds of mourners at his funeral.<br />

Next <strong>Stage</strong>: The Three Sisters | 10

“It is time for writers to admit that nothing in this world makes sense.<br />

Only fools and charlatans think they know and understand everything.”<br />

Snapshots Out of Time<br />

Army Life and Codes of Honor<br />

Writing about The Three Sisters, <strong>Chekhov</strong> mentioned that he<br />

wanted to avoid caricatures of two things: provincial life, and<br />

military officers. Historically, service—or the desire to avoid<br />

service—in the czar’s army might have accounted for more<br />

emigration from imperial Russia than any other factor. Until 1874,<br />

draftees served basically for life. Officers had become notorious<br />

for being incompetent and brutal. When not fighting wars of<br />

imperial expansion, the army was regularly pressed into service<br />

to repress domestic uprisings and impose security on their own<br />

countrymen. Instead of this negative stereotype, or the empty<br />

cliché of spur-jingling heel-clickers, <strong>Chekhov</strong> implored his actors<br />

“to play the parts of simple, charming, decent people.” As he<br />

wrote the company, “The services have changed, you know.<br />

They’ve become more cultured, and many of them are even<br />

beginning to understand that their peace-time role is to carry<br />

culture into out-of-the way places.”<br />

While conditions in the army may have improved by 1900,<br />

the need for soldiers never slackened. Draftees were tattooed<br />

or branded to prevent their escape from service. And the idea<br />

of a deaf officer was not unlikely at all—especially in the<br />

artillery. Enlisted and officer alike were not necessarily invalided<br />

out of service, and many continued to serve even missing eyes<br />

or limbs.<br />

Next <strong>Stage</strong>: The Three Sisters | 11

“They say that in the end truth will triumph, but it’s a lie.”<br />

“Laevsky cocked his pistol when the time came to do so,<br />

and raised the cold, heavy weapon with the barrel upwards. He forgot to<br />

unbutton his overcoat, and it felt very tight over his shoulder and under<br />

his arm, and his arm rose as awkwardly as though the sleeve had been<br />

cut out of tin. Fearing that the bullet might somehow hit [his opponent]<br />

by accident, he raised the pistol higher and higher, and felt that this too<br />

obvious magnanimity was indelicate and anything but magnanimous….<br />

Thank God, [Laevsky thought,] everything would be over directly, and all<br />

that he had to do was to press the trigger rather hard….”<br />

From The Duel, by <strong>Chekhov</strong><br />

Memoirs of a Russian Maiden<br />

Another reality of military life<br />

was the duel. Made legal in 1894 when Nicholas II<br />

became czar, dueling formed as much a part of the military<br />

regime as it did the heart of a literary trope. With time on their<br />

hands, an overblown sense of their own importance, a code<br />

of honor to uphold, and drinking and gambling the common<br />

preoccupations, officers would challenge one another to pistol<br />

duels with some regularity. These were often quite harmless,<br />

as <strong>Chekhov</strong> amusingly recorded in his short story, The Duel;<br />

and when fought between fellow officers, the penalties were<br />

minimal. In the case of a soldier dueling a civilian, matters were<br />

more serious and could result in imprisonment.<br />

After the army detachment had gone, and with it<br />

most of the officers, [town] grew quiet again. The<br />

military band left by steamer…and our dear old Fedor<br />

once again sat on his chair in the middle of the club<br />

and filled the room with the resounding arpeggios<br />

of his accordion…. And so the hustle and bustle came<br />

to an end; peace and quiet came…once again. Many<br />

of our ladies began to complain of boredom. As for<br />

myself, [I was] glad that all the commotion was<br />

over and that the glamorous officers were no longer<br />

coming to the island. Mama also needed a break from<br />

the endless receptions. I began to dream more often<br />

of going to Petersburg…. But how could I get there? I<br />

had no answer to that question.<br />

From <strong>By</strong>gone Days, the memoirs of Emiliia Pimenova<br />

Next <strong>Stage</strong>: The Three Sisters | 12

“Love” Letters<br />

To Mikhail <strong>Chekhov</strong> [his brother]<br />

Yalta<br />

26 October, 1898<br />

Dear Michel,<br />

[…]As for your insistence on marriage, what can I say? Marriage<br />

for love is the only kind of marriage that’s interesting. Marrying<br />

a girl only because she’s nice is like buying something you don’t<br />

need at a market merely because it is pretty. The point around<br />

which family life revolves is love, sexual attraction, one flesh.<br />

Everything else is dreary and unreliable, no matter how cleverly<br />

it is calculated. Therefore, the point is one of finding a girl you<br />

love, not one you think is nice. As you see, a mere bagatelle is all<br />

that’s holding us back.<br />

<strong>Anton</strong> and Olga<br />

Yours,<br />

A. <strong>Chekhov</strong><br />

To <strong>Anton</strong> <strong>Chekhov</strong><br />

Yalta<br />

24 May, 1901<br />

Dear Antosha,<br />

I will now permit myself to state my opinion about<br />

your marriage. To my mind, the whole business of<br />

weddings is appalling! And you would be much better<br />

off without all that unnecessary fuss. If a certain<br />

person loves you, she’s not going to leave you and<br />

there is no sacrifice entailed on her part, nor the<br />

slightest selfishness on yours. How could you ever think<br />

such a thing?...You can always get hitched later on. Tell<br />

that to your Knippschütz [Olga] from me…. In any case,<br />

do what you think is right; it might well be that I am<br />

being partial in this particular case. But you yourself<br />

brought me up not to have any prejudices.<br />

Yours,<br />

Maria<br />

To Maria <strong>Chekhov</strong>a [his sister]<br />

Axyonovo<br />

4 June, 1901<br />

Dear Masha,<br />

The letter in which you advised me not to get married was<br />

forwarded to me…and I received it here yesterday. I don’t know<br />

if I’ve made a mistake or not, but I got married mainly because,<br />

first, I’m over forty; second, Olga comes from a highly moral<br />

family; and third, if we have to separate, I’ll do so without<br />

the least hesitation, as if I had never gotten married. Another<br />

important consideration is that my marriage has not in the<br />

least changed either my way of life or the way of life of those<br />

who lived and are living around me. Everything, absolutely<br />

everything will remain just as it was, and I’ll go on living alone<br />

in Yalta as before.<br />

Yours,<br />

<strong>Anton</strong><br />

Next <strong>Stage</strong>: The Three Sisters | 14

Glossary<br />

Compiled by Gavin Witt, Production Dramaturg<br />

“forget thy wrath, Aleko”—Solyony quotes from, and refers to<br />

the hero of—The Gypsies, an epic poem by legendary Russian<br />

poet Alexander Pushkin—who, incidentally, died in a duel.<br />

Aleko is a hot-blooded youth who falls in love with a very<br />

pretty—and very married—young gypsy woman. She cannot<br />

resist the handsome Aleko, and their illicit affair comes to an<br />

abrupt and violent conclusion at the hands of her husband.<br />

In 1893, at 19, then-student Sergei Rachmaninoff composed<br />

an opera, Aleko, based on The Gypsies. See Pushkin entry in<br />

additional material on page 16.<br />

“Balzac was married in Berdichev”—Balzac was an influential<br />

French novelist and one of the founders of literary Realism in<br />

Europe. In 1850, already dying, he did indeed travel to Berdichev<br />

(or Berdyczow) in Poland, where he married a wealthy woman<br />

with whom he’d long corresponded. He died three months<br />

later. Merely a coincidence, no doubt.<br />

“Our new battery commander”—Lt. Col. Vershinin commands<br />

an artillery battery—a group of field guns and their support,<br />

about 285 men—the equivalent of an infantry company within<br />

the larger regiment.<br />

“Moscow burned down too”—When Napoleon invaded Russia<br />

in 1812, the Russians burned everything to deprive the French<br />

troops of their conquest. When they finally burned Moscow as<br />

well, Napoleon’s army began its disastrous and deadly retreat<br />

back to France.<br />

Carnival—pre-Lenten festivities much like Mardi Gras,<br />

celebrated in Russian folk tradition with parties, music, and<br />

costume parades.<br />

Copernicus—15 th -century astronomer and mathematician who,<br />

studying the solar system, first suggested that the sun and<br />

not the earth was the center of the cosmic dance. With Galileo,<br />

one of the founders of modern astronomy. Vershinin equates<br />

Copernicus with Columbus for the latter’s part in disproving<br />

the flat-earth theories of his day.<br />

Dobrolyubov—influential Russian liberal, a literary and social<br />

critic in the mid-19 th Century.<br />

epidemic—widespread outbreak of a highly contagious<br />

disease simultaneously affecting a large number of people<br />

in a community or region. As a doctor, <strong>Chekhov</strong> several times<br />

helped provide medical care during regional epidemics—most<br />

notably of cholera.<br />

Gogol—Russian master of satirical comedy, most famous for<br />

The Inspector General and his absurdist short stories.<br />

highfalutin—pretentious or fancy; pompous<br />

Lermontov—Solyony fancies himself in the mold of the Russian<br />

Romantic poet Mikhail Lermontov, a <strong>By</strong>ronic figure who died in<br />

a duel before he was 30. <strong>Chekhov</strong>, however, was quite clear in<br />

his notes that any resemblance to Lermontov was entirely in<br />

Solyony’s head. See additional material on page 17.<br />

Moscow—the principal city of eastern, or Slavic, Russia, as<br />

distinguished from the western, or European, St. Petersburg.<br />

Unlike St. Petersburg’s regular street plan, broad boulevards,<br />

and urbane sophistication, Moscow in <strong>Chekhov</strong>’s day was<br />

notoriously unkempt, disordered, and chaotic.<br />

naphtha—A highly volatile, flammable liquid distilled from<br />

petroleum, coal tar, and natural gas and used as fuel or as a<br />

solvent—a fairly dangerous choice of hair-care products.<br />

rubles—basic unit of currency in Russia (consisting of 100<br />

kopeks per ruble). In 1901, a generous annual salary was 150<br />

rubles; the money Andrey has lost gambling represents a very<br />

hefty sum.<br />

samovar—a metal urn with a spigot, heated by spirits or coals,<br />

traditionally used to heat water for tea. The gift Chebutykin<br />

presents is inappropriately elaborate, embarrassing Irina.<br />

sophistry—an intentionally false but logically plausible<br />

argument usually intended to deceive someone.<br />

“there’s a storm coming”—Only four years after the premiere<br />

of The Three Sisters, the 1905 Revolution broke out all over<br />

Russia in response to the dire need for social and economic<br />

reform at all levels. Tuzenbach alludes to the fairly obvious<br />

stirrings of revolt, which ultimately led to the Bolshevik<br />

Revolution and the overthrow of the czar in 1917.<br />

“wearing a white dress”—as distinguished from the mourning<br />

black Irina would have been wearing for the past year in honor<br />

of her father’s death. See additional material on page 15.<br />

“don’t whistle like that”—Superstition held that by whistling<br />

inside the house, you might “whistle your money away.”<br />

Eugene Onegin—In the midst of <strong>Chekhov</strong>’s Act III, Vershinin<br />

sings a passage from Tchaikovsky’s opera Eugene Onegin—the<br />

famous basso aria sung in the opera’s own third act by Prince<br />

Gremin, who has married Onegin’s true love, Tatiana. “Love<br />

is appropriate to any age,” Gremin sings; “its delights are<br />

beneficent.” The opera, one of Tchaikovsky’s masterworks,<br />

was based on the poem of the same name by Pushkin.<br />

Next <strong>Stage</strong>: The Three Sisters | 14

Glossary<br />

Continued<br />

>>><br />

Additional Allusions and Expanded Context<br />

Mourning<br />

The opening scene of The Three Sisters presents not only<br />

youngest sister Irina’s birthday celebration, but the one-year<br />

anniversary of the death of the sisters’ father—a significant<br />

landmark in the highly structured language of mourning at<br />

the time.<br />

The mourning for parents ranks next to that of<br />

widows. It lasts in either case twelve months—<br />

six months in crape trimmings, three in plain<br />

black, and three in half mourning. It is, however,<br />

better to continue the plain black to the end<br />

of the year, and wear half-mourning for three<br />

months longer.<br />

cities, St. Petersburg and Moscow, in 1851. It took a year and a<br />

half to build the 402-mile route between the two cities, one<br />

of the straightest railways in the world. The first train to try<br />

the new line set off from St. Petersburg and spent almost 22<br />

hours en route to Moscow. In 1891, Czar Nicholas II inaugurated<br />

the construction of the Trans-Siberian Railway, the longest<br />

continuous railway on the earth. In 1901, the nearly 800-mile<br />

railway journey to Moscow from Perm, the likely setting of The<br />

Three Sisters, would have been a considerable journey in time<br />

and logistics alone.<br />

At the end of the six months crape can be put<br />

aside, and plain black, such as cashmere, worn,<br />

trimmed with silk if liked, but not satin for that<br />

is…never worn by those who strictly attend to<br />

mourning etiquette.<br />

Many persons think it is in better taste not<br />

to commence half-mourning until after the<br />

expiration of a year, except in the case of young<br />

children, who are rarely kept in mourning<br />

beyond the twelve months.<br />

—Victorian Mourning Customs from Collier’s<br />

Cyclopedia, 1901<br />

Railways in Russia<br />

Russia includes an enormous expanse of territory that, even<br />

today, takes eight days to cross by rail. Like the United States,<br />

much of Russia was made accessible only when the country’s<br />

rail system was built in the 19 th Century. The first Russian<br />

train started from the then-capital St. Petersburg on October<br />

30, 1837. The first national railroad was just 19 miles long,<br />

connecting St. Petersburg with the suburb of Tsarskoye Selo.<br />

The first Russian main line connected the country’s two leading<br />

Dueling in 19 th -century Russia<br />

In a typical duel, each party acted through a partner or<br />

associate known as the second. The second’s primary duties<br />

were to deliver the challenge for the offended party, oversee<br />

the logistics of the actual duel (place, time, and weapons)—<br />

and at least to go through the motions of trying to reconcile<br />

the parties without violence.<br />

Once a challenge was issued, the offending party had the<br />

option to apologize, in which case the matter was honorably<br />

resolved. If he elected to fight, he was entitled to choose<br />

the weapons, the time, and the place of the encounter. Most<br />

duels in Russia in the 19 th Century were fought with muzzleloading<br />

dueling pistols, with the duelists taking turns firing at<br />

a measured distance. Up until combat began, apologies could<br />

be given and the duel stopped. After combat began, it could be<br />

stopped at any point after honor had been satisfied.<br />

Until 1894, duels were illegal; participants were, at least<br />

technically, guilty of attempted murder if everyone survived, or<br />

murder if anyone was killed. This included not only the duelists<br />

themselves, but seconds and anyone else taking part. Officers<br />

taking part in duels could be demoted and have to wear a<br />

white fatigue uniform cap denoting their punishment; some<br />

lesser-ranking officers were known to dress to pretend they<br />

had been in duels, to impress the ladies. >>><br />

Next <strong>Stage</strong>: The Three Sisters | 15

Glossary<br />

Continued<br />

>>><br />

Duels were a popular part of literature at the time. Pushkin<br />

published one story, The Shot, that offered a perspective on<br />

the action:<br />

I was calmly enjoying my reputation, when<br />

a young man belonging to a wealthy and<br />

distinguished family joined our regiment. Never<br />

in my life have I met with such a fortunate<br />

fellow! Imagine to yourself youth, wit, beauty,<br />

unbounded gaiety, the most reckless bravery,<br />

a famous name, untold wealth. My supremacy<br />

was shaken. I took a hatred to him. His success<br />

in the regiment and in the society of ladies<br />

brought me to the verge of despair. I began to<br />

seek a quarrel with him. At last, at a ball, seeing<br />

him the object of the attention of all the ladies…<br />

I whispered some grossly insulting remark in his<br />

ear. He flamed up and gave me a slap in the face.<br />

We grasped our swords; the ladies fainted; we<br />

were separated; and that same night we set out<br />

to fight.<br />

[…]”Don’t you agitate yourself,” laughed Von<br />

Koren. “You can set your mind at rest; the duel<br />

will end in nothing. Laevsky will magnanimously<br />

fire into the air—he can do nothing else; and I<br />

daresay I shall not fire at all. To be arrested and<br />

lose my time on his account–the game’s not<br />

worth the candle.”<br />

“<strong>By</strong> the way, what is the punishment for<br />

dueling?”<br />

“Arrest, and in the case of the death of<br />

your opponent a maximum of three years’<br />

imprisonment in the fortress.”<br />

“The fortress of St. Peter and St. Paul?”<br />

“No, in a military fortress, I believe.”<br />

“Though this fine gentleman ought to have a<br />

lesson!”<br />

The dawn was just breaking. I was standing<br />

at the appointed place with my three seconds<br />

[when] I saw him coming in the distance. We<br />

advanced to meet him. The seconds measured<br />

twelve paces for us. …It was decided that we<br />

should cast lots. The first number fell to him,<br />

the constant favorite of fortune. He took aim,<br />

and his bullet went through my cap. It was now<br />

my turn. His life at last was in my hands….<br />

—from The Shot by Pushkin<br />

And from <strong>Chekhov</strong>’s own pen:<br />

Whether he killed Von Koren next day or left<br />

him alive, it would be just the same, equally<br />

useless and uninteresting. Better to shoot him<br />

in the leg or hand, wound him, then laugh at<br />

him, and let him, like an insect with a broken leg<br />

lost in the grass–let him be lost with his obscure<br />

sufferings in the crowd of insignificant people<br />

like himself.<br />

Laevsky went to Sheshkovsky, told him all<br />

about it, and asked him to be his second; then<br />

they both went to the superintendent of the<br />

postal telegraph department, and asked him,<br />

too, to be a second, and stayed to dinner with<br />

him. At dinner there was a great deal of joking<br />

and laughing. Laevsky made jests at his own<br />

expense, saying he hardly knew how to fire off<br />

a pistol, calling himself a royal archer and<br />

William Tell. “We must give this gentleman a<br />

lesson” he said.<br />

Pushkin<br />

Aleksandr Sergeyevich Pushkin was born in Moscow in 1799,<br />

the great-grandson of an African who had emigrated to Russia<br />

and served Czar Peter the Great. His first published poem<br />

appeared in 1814, before he’d even graduated. >>><br />

Next <strong>Stage</strong>: The Three Sisters | 16

Glossary<br />

Continued<br />

>>><br />

After graduating, he continued to write and made a name for<br />

himself among liberal circles with poems touting freedom and<br />

revolution. He also began work on his first major work, Ruslan<br />

and Ludmila—based on Russian folktales he’d heard as a young<br />

man. <strong>By</strong> 1820, his political poems led to exile to South Russia,<br />

where he started what would become his monumental novel<br />

in verse, Eugene Onegin.<br />

Transferred to Odessa in 1823, he joined the social whirl and<br />

engaged in love affairs with two married women. There he<br />

also began what would become the epic poem The Gypsies.<br />

However, his political views got him exiled again, to his family’s<br />

estate in north Russia.<br />

He remained under surveillance in this new exile for two more<br />

years, all the while continuing his literary pursuits—including<br />

writing Boris Godunov. Despite being implicated indirectly in<br />

the Decembrist Uprising of 1825, Pushkin ultimately won the<br />

Czar’s reprieve—though his freedom was constrained and each<br />

word he wrote overseen by police censors.<br />

Despite these constraints, Pushkin continued to write and<br />

publish, and even managed to get married. His wife’s beauty<br />

won her many admirers, the Czar included, and Pushkin<br />

became increasingly jealous. He had good reason, for, in 1834,<br />

his wife met a handsome French royalist émigré in Russian<br />

service, named D’Anthes, who pursued her so openly that,<br />

after two years, it had become a very public scandal. After<br />

challenging D’Anthes, Pushkin met him for a duel on January 27,<br />

1837. D’Anthes fired first, and Pushkin was mortally wounded.<br />

He died two days later.<br />

Pushkin works adapted into operas include: Ruslan and<br />

Ludmila (Glinka); The Gypsies (Alek, Rachmaninov); Eugene<br />

Onegin and The Queen of Spades (Tchaikovsky); Boris Godunov<br />

(Mussorgsky); and The Golden Cockerel (Rimsky-Korsakov).<br />

Lermontov<br />

Mikhail Yurevich Lermontov was a Russian poet and novelist<br />

born in 1814, son of a retired army captain. Taken up after his<br />

mother’s death by his wealthy grandmother, who stood by him<br />

through the rest of his life, Lermontov began writing poetry<br />

as a teenager at an elite boarding school for nobility. He later<br />

attended the notoriously liberal Moscow University.<br />

While his early verses mostly imitated English Romantic poet<br />

<strong>By</strong>ron, Lermontov first won public attention with his poem<br />

“On the Death of the Poet,” written to protest Pushkin’s death.<br />

For his poem, which accused the government of complicity, he<br />

was exiled to the Caucasus, where he had recuperated from<br />

illness as a child. While there, he was inspired by much of the<br />

exotic and alien land—writing, drawing, and absorbing the<br />

Caucasian milieu.<br />

As a result of zealous intercession by his grandmother,<br />

Lermontov was allowed to return to the capital in 1838. He<br />

cultivated a skeptical, devil-may-care attitude, while his<br />

published poems and his political views earned him favor<br />

among writers, journalists, and society women. His 1840 novel,<br />

A Hero of our Time, was partly autobiographical, telling of a<br />

disenchanted and bored nobleman devoted only to seeking<br />

new sensations—including a deadly climactic duel. The novel<br />

became an overnight sensation, and cemented Lermontov’s<br />

literary reputation.<br />

Also in 1840, however, Lermontov was tried and sentenced<br />

for his duel with the son of the French ambassador; he was<br />

sent, on the Czar’s orders, to an infantry regiment preparing<br />

for dangerous military operations. Forced to take part in<br />

bloody hand-to-hand battles, Lermontov distinguished himself<br />

admirably and was allowed leave for medical treatment.<br />

While on leave, he quarreled and was challenged to another<br />

duel—where the 26-year-old poet was shot and killed, just like<br />

his hero Pushkin. His death won from Czar Nicholas I the curt<br />

response, “a dog’s death for a dog.” The natural enemy of the<br />

Crown and the State, Lermontov was beloved by many for his<br />

embrace of freedom both personal and political. ●<br />

Next <strong>Stage</strong>: The Three Sisters | 17

Annotated Bibliogr aphy<br />

Compiled by Dina Epshteyn, Associate Production Dramaturg<br />

For more information on <strong>Anton</strong> <strong>Chekhov</strong>, his life and work:<br />

Bartlett, Rosamund. <strong>Chekhov</strong>: Scenes from a Life. London, UK: The Free Press, 2005.<br />

—An impressionistic sketch of <strong>Chekhov</strong>’s life and environment.<br />

Rayfield, Donald. <strong>Anton</strong> <strong>Chekhov</strong>: A Life. New York, NY: Henry Holt and Company, 1997.<br />

—A newer, full biography including the latest information released from Soviet archives.<br />

Troyat, Henri. <strong>Chekhov</strong>. New York, NY: E.P. Dutton, 1986.<br />

—The first truly comprehensive American biography of <strong>Chekhov</strong>.<br />

<strong>Anton</strong> <strong>Chekhov</strong> and His Times. Edited by Andrei Turkov. Translated from the Russian by Cynthia Carlile and Sharon McKee.<br />

Fayetteville, AR: University of Arkansas Press, 1995.<br />

—Provides first-hand material as well as commentary on <strong>Chekhov</strong> from his contemporaries.<br />

Letters of <strong>Anton</strong> <strong>Chekhov</strong>. Edited by Simon Karlinsky. Translated by Michael Henry Heim. New York,<br />

NY: Harper & Row, Publishers, 1973.<br />

—<strong>Chekhov</strong>’s life in the first person: a selection of his letters to various friends, family members, and colleagues.<br />

For more information on Russian culture and history:<br />

Figes, Orlando. Natasha’s Dance: A Cultural History of Russia. New York, NY: Metropolitan Books, Henry Holt and Company, 2002.<br />

—A thorough cultural history of Russia from 1700 to 1970. Includes glossary and chronology.<br />

Hasler, Joan. The Making of Russia: From Prehistory to Modern Times. New York, NY: Delacorte Press, 1969.<br />

—A history of Russia with great sections on everyday life, the social classes, and politics.<br />

Hosking, Geoffrey. Russia: People and Empire. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1997.<br />

—An extremely detailed history of Imperial Russia, exploring all aspects of cultural and political life from 1552 to 1917.<br />

Before the Revolution: St. Petersburg in Photographs: 1890-1914. Compiled by Mikhail P. Iroshnikov, Liudmila A. Protsai, and Yury B.<br />

Shelayev. New York, NY: Harry N. Abrams, 1991.<br />

—Striking photographic record of St. Petersburg around the time of The Three Sisters, with commentary.<br />

A Portrait of Tsarist Russia: Unknown Photographs from the Soviet Archives. New York, NY: Pantheon Books, 1989.<br />

—A photo record of Imperial Russia with explanatory text.<br />

Russia Through Women’s Eyes: Autobiographies from Tsarist Russia. Edited by Toby W. Clyman and Judith Vowles. New Haven, CT:<br />

Yale University Press, 1996.<br />

—First-hand accounts from women about their lives in 19th-century Russia.<br />

If you have any trouble using this study guide—or for more<br />

information on CENTERSTAGE’s education programs—call us<br />

at 410.986.4050. Student group rates start at just $15. Call<br />

Group Sales at 410.986.4008 for more information, or visit<br />

www.centerstage.org.<br />

Material in our Next <strong>Stage</strong> resource guide is made available free of charge for<br />

legitimate educational and research purposes only. Selective use has been made<br />

of previously published information and images whose inclusion here does<br />

not constitute license for any further re-use of any kind. All other material is<br />

the property of CENTERSTAGE, and no copies or reproductions of this material<br />

should be made for further distribution, other than for educational purposes,<br />

without express permission from the authors and CENTERSTAGE.<br />

Next <strong>Stage</strong>: Next <strong>Stage</strong>: The Three The Three Sisters Sisters | 18 | 19