1hmPUyl

1hmPUyl

1hmPUyl

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

BUSINESSOFGOVERNMENT.ORG SPRING 2014<br />

The Business of Government<br />

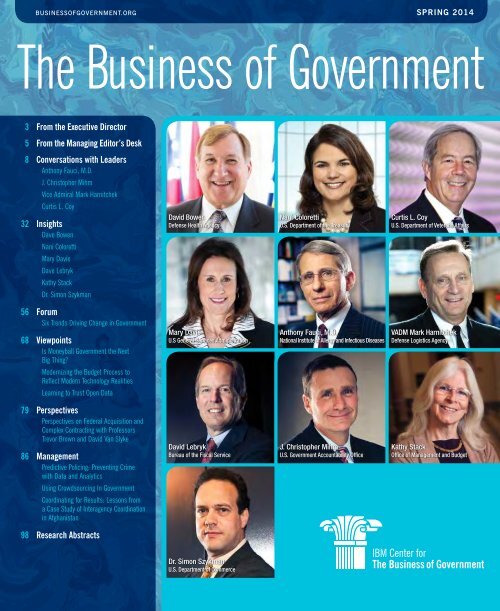

3 From the Executive Director<br />

5 From the Managing Editor’s Desk<br />

8 Conversations with Leaders<br />

Anthony Fauci, M.D.<br />

J. Christopher Mihm<br />

Vice Admiral Mark Harnitchek<br />

Curtis L. Coy<br />

32 Insights<br />

Dave Bowen<br />

David Bowen<br />

Defense Health Agency<br />

Nani Coloretti<br />

U.S. Department of the Treasury<br />

Curtis L. Coy<br />

U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs<br />

Nani Coloretti<br />

Mary Davie<br />

Dave Lebryk<br />

Kathy Stack<br />

Dr. Simon Szykman<br />

56 Forum<br />

Six Trends Driving Change in Government<br />

68 Viewpoints<br />

Is Moneyball Government the Next<br />

Big Thing?<br />

Mary Davie<br />

U.S General Services Administration<br />

Anthony Fauci, M.D.<br />

National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases<br />

VADM Mark Harnitchek<br />

Defense Logistics Agency<br />

Modernizing the Budget Process to<br />

Reflect Modern Technology Realities<br />

Learning to Trust Open Data<br />

79 Perspectives<br />

Perspectives on Federal Acquisition and<br />

Complex Contracting with Professors<br />

Trevor Brown and David Van Slyke<br />

86 Management<br />

Predictive Policing: Preventing Crime<br />

with Data and Analytics<br />

David Lebryk<br />

Bureau of the Fiscal Service<br />

J. Christopher Mihm<br />

U.S. Government Accountability Office<br />

Kathy Stack<br />

Office of Management and Budget<br />

Using Crowdsourcing In Government<br />

Coordinating for Results: Lessons from<br />

a Case Study of Interagency Coordination<br />

in Afghanistan<br />

98 Research Abstracts<br />

Dr. Simon Szykman<br />

U.S. Department of Commerce

INFORMATIVE<br />

INSIGHTFUL<br />

IN-DEPTH<br />

THE BUSINESS OF<br />

GOVERNMENT HOUR<br />

• Conversations with government executives<br />

• Sharing management insights, advice, and best practices<br />

• Changing the way government does business<br />

ON THE AIR<br />

Mondays at 11:00 am<br />

Wednesdays at Noon<br />

Federal News Radio,<br />

WFED (1500 AM)* or at<br />

federalnewsradio.com<br />

ANYWHERE, ANYTIME<br />

Download current and archived shows:<br />

businessofgovernment.org<br />

* Washington, D.C. area only

Table of Contents<br />

From the Executive Director<br />

By Daniel Chenok.....................................................................................3<br />

From the Managing Editor’s Desk<br />

By Michael J. Keegan.................................................................................5<br />

Conversations with Leaders<br />

Anthony Fauci, M.D.<br />

Director, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases ................. 8<br />

J. Christopher Mihm<br />

Managing Director, Strategic Issues<br />

Government Accountability Office ........................................................ 14<br />

Vice Admiral Mark Harnitchek<br />

Director, Defense Logistics Agency ........................................................ 20<br />

Curtis L. Coy<br />

Deputy Under Secretary for Economic Opportunity, Veterans<br />

Benefits Administration, U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs .................. 26<br />

Insights<br />

Pursuing IT Standardization and Consolidation:<br />

Insights from Dave Bowen, Director of Health Information<br />

Technology and Chief Information Officer, Defense Health Agency<br />

U.S. Department of Defense.......................................................................... 32<br />

Managing Resources in an Era of Fiscal Constraint and Reform:<br />

Insights from Nani Coloretti, Assistant Secretary of the Treasury for<br />

Management, U.S. Department of the Treasury ............................................ 36<br />

Maximizing the Value of Government IT: Insights from Mary Davie<br />

Assistant Commissioner, Office of Integrated Technology Services<br />

Federal Acquisition Service, U.S General Services Administration...............40<br />

Promoting the Financial Integrity of the U.S. Government: Insights<br />

from Dave Lebryk, Commissioner, Bureau of the Fiscal Service<br />

U.S. Department of the Treasury ................................................................... 44<br />

Harnessing Evidence and Evaluation: Insights from Kathy Stack<br />

Advisor, Evidence-Based Innovation, Office of Management and Budget .......48<br />

Data and Information as Strategic Assets:<br />

Insights from Dr. Simon Szykman, Chief Information Officer<br />

U.S. Department of Commerce .................................................................... 52<br />

Forum<br />

Six Trends Driving Change in Government.............................................. 56<br />

SPRING 2014 IBM Center for The Business of Government 1

Table of Contents (continued)<br />

Viewpoints<br />

Is Moneyball Government the Next Big Thing?<br />

By John M. Kamensky.............................................................................68<br />

Modernizing the Budget Process to Reflect Modern Technology<br />

Realities<br />

By Daniel Chenok...................................................................................73<br />

Learning to Trust Open Data<br />

By Gadi Ben-Yehuda...............................................................................76<br />

Perspectives<br />

Introduction: Perspectives on Federal Acquisition and Complex<br />

Contracting<br />

By Michael J. Keegan...............................................................................79<br />

Perspectives on Federal Acquisition and Complex Contracting<br />

with Professors Trevor Brown and David Van Slyke<br />

By Michael J. Keegan...............................................................................80<br />

Management<br />

Predictive Policing: Preventing Crime with Data and Analytics<br />

By Jennifer Bachner.................................................................................86<br />

Using Crowdsourcing In Government<br />

By Daren C. Brabham.............................................................................91<br />

Coordinating for Results: Lessons from a Case Study of Interagency<br />

Coordination in Afghanistan<br />

By Andrea Strimling Yodsampa................................................................95<br />

Research Abstracts<br />

Realizing the Promise of Big Data.......................................................... 98<br />

Engaging Citizens in Co-Creation in Public Services................................. 98<br />

Eight Actions to Improve Defense Acquisition........................................ 98<br />

Incident Reporting Systems: Lessons from the Federal Aviation<br />

Administration’s Air Traffic Organization................................................ 99<br />

Cloudy with a Chance of Success: Contracting for the Cloud in<br />

Government........................................................................................... 99<br />

Using Crowdsourcing In Government.................................................... 99<br />

Federal Ideation Programs: Challenges and Best Practices.................... 100<br />

Six Trends Driving Change in Government........................................... 100<br />

Coordinating for Results: Lessons from a Case Study of<br />

Interagency Coordination in Afghanistan.............................................. 100<br />

Predictive Policing: Preventing Crime with Data and Analytics............ 101<br />

Collaboration Between Government and Outreach Organizations:<br />

A Case Study of the Department of Veterans Affairs.............................. 101<br />

A Guide for Agency Leaders on Federal Acquisition............................... 101<br />

The Business of Government<br />

A Publication of the IBM Center for The Business of Government<br />

Daniel Chenok<br />

Executive Director<br />

John M. Kamensky<br />

Senior Fellow<br />

Michael J. Keegan<br />

Managing Editor<br />

The Business of Government magazine and<br />

Host/Producer, The Business of Government Hour<br />

Ruth Gordon<br />

Business and Web Manager<br />

Gadi Ben-Yehuda<br />

Innovation and Social Media Director<br />

IBM Center for The Business of Government<br />

600 14th Street, NW, Second Floor<br />

Washington, DC 20005<br />

For subscription information, call (202) 551-9342. Web page:<br />

www.businessofgovernment.org. Copyright 2014 IBM Global<br />

Business Services. All rights reserved. No part of this<br />

publication may be reproduced in any form, by microfilm,<br />

xerography, or otherwise, without the written permission<br />

of the copyright owner. This publication is designed to<br />

provide accurate information about its subject matter, but<br />

is distributed with the understanding that the articles do not<br />

constitute legal, accounting, or other professional advice.<br />

How to Order Recent Publications.......................................................102<br />

2<br />

www.businessofgovernment.org<br />

The Business of Government

From the Executive Director<br />

Six Trends Driving Change in Government: Examples of<br />

Agencies Leveraging Change<br />

Since the creation of the IBM Center for The Business of Government over 15 years ago,<br />

it has been our goal to help public sector leaders and managers address real-world problems<br />

by sponsoring independent, third-party research from top minds in academe and the<br />

nonprofit sector.<br />

Daniel Chenok is Executive<br />

Director of the IBM Center for<br />

The Business of Government.<br />

His e-mail: chenokd@us.ibm.com.<br />

We aim to produce research and analysis that help government leaders respond more<br />

effectively to their mission and management challenges. The IBM Center is named “The<br />

Business of Government” because we focus on the management and operation of government,<br />

not the policies of government. Public sector leaders and managers need the best,<br />

most practical advice available when it comes to delivering the business of government.<br />

We seek to bridge the gap between research and practice by helping to stimulate and<br />

accelerate the production of research that points to actionable recommendations.<br />

Over the past several months, the Center for the Business of Government has been examining<br />

trends in six different areas that are driving government to approach mission and<br />

business challenges differently, pointing to the need for further analysis and recommendations<br />

on how to effect change across these six areas. The Center reviewed these trends<br />

and released a special report, Six Trends Driving Change in Government. The Forum in this<br />

edition offers a primer on each of the six trends and the insights that can help gov ernment<br />

executives respond more effectively to their mission and management chal lenges. The<br />

Center’s research agenda is informed by these trends, but some federal agencies have<br />

already started down a positive path of change in each trend area, and their ideas can<br />

serve as models for others to adapt as appropriate.<br />

Such examples include:<br />

Performance. The Department of Education has created a What Works Clearinghouse of<br />

successful policies, programs, and practices that provide educators in the field with the<br />

best information available so they can make evidence-based decisions regarding curriculum<br />

and other education-based initiatives.<br />

Risk. The Internal Revenue Service established a new Chief Risk Officer to help agency<br />

leaders understand risks in advance, and develop strategies that support the delivery of<br />

taxpayer services that account for, communicate, and mitigate risks.<br />

Innovation. The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) has introduced a portal<br />

called the Project Catalyst, through which they achieve three of the goals laid out in this<br />

section. The CFPB allows visitors to the site to (1) “Pitch a Pilot,” (2) “Run a Disclosure<br />

Trial,” and (3) “Use Our Data.” They are doing so in order to “engage with the innovator<br />

community; participate in initiatives that inform our policy work; and stay on top of<br />

emerging trends to remain a forward-looking organization.”<br />

SPRING 2014 IBM Center for The Business of Government 3

From the Executive Director<br />

Efficiency. The General Services Administration has saved over $1 billion through actions<br />

taken by its Information Technology Service to create a marketplace that will provide<br />

agencies with buying options, access to data and information, access to expertise, and<br />

an improved buying experience.<br />

Mission and Leadership. Mission support chiefs within the Departments of Veterans Affairs<br />

and Agriculture convene on a regular basis to share their progress on various initiatives<br />

and to identify ways to work together, for example on telework strategies and reducing<br />

their real estate footprints. Success in any of these initiatives often involves leaders collaborating<br />

with multiple mission-support organizations in order to be successful.<br />

This issue highlights successful actions being taken throughout government to meet challenges<br />

of ever-increasing complexity, and sparks thinking among government leaders and<br />

stakeholders about how best to forge new paths forward. ¥<br />

4<br />

www.businessofgovernment.org<br />

The Business of Government

From the Managing Editor’s Desk<br />

By Michael J. Keegan<br />

In meeting varied missions, government executives confront significant challenges.<br />

Responding properly to them must be guided and informed by the harsh fiscal and<br />

budgetary realities of the day. It can no longer be simply a wishful platitude that government<br />

do more with less. Leaders need to change the way government does business to<br />

make smarter use of increasingly limited resources—leveraging technology and innovation<br />

to be more efficient, effective, anticipatory, adaptive, and evidence-based in delivering<br />

missions and securing the public trust.<br />

Michael J. Keegan is Managing<br />

Editor of The Business of<br />

Government magazine and<br />

Host/Producer of The Business<br />

of Government Hour. His<br />

e-mail: michael.j.keegan@<br />

us.ibm.com.<br />

Government executives, however, must also avoid the tyranny of the present or the next<br />

budget cycle, and recognize that the challenges of today often morph into the hazards of<br />

tomorrow. So anticipating the future—getting ahead of events rather than being subsumed<br />

by them—becomes integral to positioning, resourcing, and preparing an agency for what<br />

may come, while always keeping focused on primary responsibilities.<br />

This edition of The Business of Government magazine underscores the importance of<br />

correlating short-term decision-making with long-range consequences. We highlight the<br />

latest trends and best practices for improving government effectiveness by introducing you<br />

to key government executives, detailing the work of public management practitioners, and<br />

offering insights from leading academics.<br />

Forum on Six Trends Driving Change in Government<br />

Fiscal austerity, citizen expectations, the pace of technology and innovation, and a new<br />

role for governance make for trying times. These challenges influence how government<br />

executives lead today, and more important, how they can prepare for the future. It is anticipating<br />

the future—using foresight in government—that can deepen our understanding of<br />

the forces driving change.<br />

In a special report, Six Trends Driving Change in Government, the IBM Center for The<br />

Business of Government has identified trends that correspond to these challenges and<br />

drive government change. Separately and in combination, they paint a path forward in<br />

responding to the ever-increasing complexity government faces.<br />

The areas covered by Six Trends are performance, risk, innovation, mission, efficiency,<br />

and leadership. Focusing on these has the potential to change the way government does<br />

business. This forum reflects our sense of what lies ahead, providing an excerpt of the<br />

Six Trends special report. We hope these insights are instructive and ultimately helpful to<br />

today’s government leaders and managers. For a more in-depth exploration of each trend,<br />

download or order a free copy of the full report at businessofgovernment.org.<br />

Conversations with Leaders<br />

Throughout the year, I have the pleasure of speaking with key government executives and<br />

public sector leaders about their agencies, accomplishments, and vision of government in<br />

the 21st Century. The four profiled manifest the leadership and strategic foresight needed<br />

to meet their varied missions.<br />

SPRING 2014 IBM Center for The Business of Government 5

From the Managing Editor’s Desk<br />

• Dr. Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases,<br />

leads an agency that has for 60 years been at the forefront of research in infectious<br />

and immune mediated diseases, microbiology, and immunology. Dr. Fauci outlines<br />

his agency’s strategic priorities, how NIAID accelerates basic research into health care<br />

practice, and the lessons learned from studying emerging and reemerging infectious<br />

diseases.<br />

• Chris Mihm, managing director for strategic issues at the U.S. Government<br />

Accountability Office, describes his group’s work in three broad areas—oversight,<br />

insight, and foresight. His oversight mission focuses on making sure that funds are<br />

expended for their intended purposes. Mihm also offers insights into what works, identifying<br />

best practices that can be leveraged and adopted, where appropriate, across<br />

government. Finally, what he calls foresight involves pinpointing emerging trends,<br />

making Congress aware of them, and informing them of the trends’ possible implications<br />

for public policy and governance.<br />

• Vice Admiral Mark Harnitchek, director of the Defense Logistics Agency, is charged<br />

with providing full-spectrum logistical support to the armed services and civilians<br />

around the world every day and for every major conflict over the past five decades.<br />

Logistics is a cost driver that must be managed with deliberate precision. Admiral<br />

Harnitchek recognizes that the very nature of envisioned threats and conflicts over the<br />

next decade, combined with increased fiscal challenges, demand an agile, joint logistics<br />

response marked by innovation and best practices.<br />

• Curtis Coy, deputy under secretary for economic opportunity within the U.S.<br />

Department of Veterans Affairs, manages a portfolio of educational and job training<br />

services for eligible veterans to enhance their economic opportunity and successful<br />

transition. With some one million veterans likely to separate or retire in the next<br />

five years and many young veterans unemployed, Coy discusses how VA promotes<br />

employment and educational opportunities for veterans and what VA is doing to<br />

enhance opportunities for veterans to obtain knowledge and skills to properly transition<br />

to civilian life.<br />

Insights from Leaders<br />

Over the past six months, I also had an opportunity to speak with public servants pursuing<br />

innovative approaches to mission achievement and citizen services. Six government executives<br />

provide insights into how they are changing the ways government does business.<br />

• Dave Bowen, chief information officer at the Defense Health Agency, shares his<br />

insights into the information technology strategy for DOD’s Defense Health Agency,<br />

how the DHA will enhance IT efforts to deliver care anytime, anywhere, and how<br />

DHA is modernizing its technology infrastructure and working toward a robust, integrated<br />

electronic health record.<br />

• Nani Coloretti, assistant secretary of the Treasury for management, offers her insights<br />

on Treasury’s management performance agenda, what her department is doing to<br />

consolidate its office space and right-size its operational footprint, and how it is<br />

working to transform the way it does business.<br />

• Mary Davie, assistant commissioner, U.S. General Services Administration’s Office of<br />

Integrated Technology Services, describes how ITS is increasing government IT’s value<br />

while lowering its cost. She identifies her office’s strategic priorities and how she is<br />

improving its operations, becoming more efficient and agile.<br />

6<br />

www.businessofgovernment.org<br />

The Business of Government

From the Managing Editor’s Desk<br />

• Dave Lebryk, commissioner, Bureau of the Fiscal Service, U.S. Department of the<br />

Treasury, outlines his insights on how the Fiscal Service transforms the way the federal<br />

government manages its financial services, what Fiscal Service does to promote<br />

the financial integrity and operational efficiency of the federal government, and<br />

how Lebryk is seeking to realize efficiency, better transparency, and dependable<br />

accountability.<br />

• Kathy Stack, advisor for evidence-based innovation at the Office of Management and<br />

Budget (OMB), describes program evaluation and how evidence and rigorous evaluation<br />

can be integrated into decision-making. She details her insights on the importance<br />

of using evidence to inform program delivery and how agencies conduct rigorous<br />

program evaluations on a tight budget.<br />

• Dr. Simon Szykman, chief information officer at the U.S. Department of Commerce,<br />

highlights the department’s information technology strategy, how it has changed the<br />

way it does IT, the challenge of cybersecurity, and much more.<br />

Perspectives on Federal Acquisition and Complex Contracting<br />

In fiscal year 2012, the federal government contracted for $517 billion in products.<br />

Complex products require more sophisticated contracting approaches. Why do federal<br />

agencies need to acquire and procure goods and services? What are the basic phases of the<br />

federal acquisition lifecycle? What are the challenges of acquiring complex products? What<br />

lessons can be learned from the Coast Guard’s Deepwater program? How can government<br />

executives most effectively manage complex acquisitions? We explore these questions and<br />

more with Professor Trevor Brown of the John Glenn School of Public Affairs at The Ohio<br />

State University, and Professor David Van Slyke of the Maxwell School of Citizenship and<br />

Public Affairs at Syracuse University.<br />

Viewpoints<br />

John Kamensky ponders whether “moneyball government” is the next big thing. Dan<br />

Chenok explores the need to modernize the budget process to reflect modern technology,<br />

and Gadi Ben-Yehuda provides his viewpoint on learning to trust open data.<br />

I close this edition with overviews of several recent Center reports. If you have not read<br />

these reports, we encourage you to do so by going to businessofgovernment.org. We hope<br />

you enjoy this edition of The Business of Government magazine. Please let us know what<br />

you think by contacting me at michael.j.keegan@us.ibm.com. I look forward to hearing<br />

from you. ¥<br />

SPRING 2014 IBM Center for The Business of Government 7

Conversations with Leaders<br />

A Conversation with Anthony Fauci, M.D.<br />

Director, National Institute of Allergy and<br />

Infectious Diseases<br />

For more than six decades, the National Institute of Allergy<br />

and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) has been at the forefront of<br />

research in infectious and immune mediated diseases, microbiology,<br />

immunology, and related disciplines. It conducts and<br />

supports basic and applied research to better understand,<br />

diagnose, prevent, and treat infectious diseases including<br />

HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis, and malaria, as well as immune<br />

mediated disorders such as lupus and asthma. This work has<br />

led to new vaccines, therapeutics, diagnostics, and other<br />

technologies that have improved health and saved millions<br />

of lives in the United States and around the world.<br />

What are the strategic priorities of NIAID? How is NIAID<br />

accelerating findings from basic research into health care<br />

practice? What have we learned from the study of emerging<br />

and reemerging infectious diseases? What’s on the horizon<br />

for NIAID? Dr. Anthony Fauci, Director of the National<br />

Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, joined me on<br />

The Business of Government Hour to explore these questions<br />

and more. The following provides an edited excerpt<br />

from our interview. – Michael J. Keegan<br />

On the Strategic Priorities for NIAID<br />

The four major areas of emphasis are:<br />

• HIV/AIDS<br />

• Infectious diseases other than HIV/AIDS, which include<br />

the standard established infections, emerging and reemerging<br />

infections, and even bio-defense such as having<br />

defense against anthrax or other attacks<br />

• Basic and clinical research into the immune system—<br />

understanding how it works, diseases of aberrant function<br />

of the immune system, or deficiency of the immune system<br />

• Global health, focusing on a vision of where we want to go<br />

Regarding HIV/AIDS, three-plus decades since the [recorded<br />

manifestation] of this devastating pandemic, we have the<br />

scientific basis for development of prevention modalities and<br />

treatment that’s highly effective. We are also on a quest for<br />

a vaccine. We feel we can turn around the trajectory of the<br />

pandemic, and within a reasonable period of time, we’ll see<br />

an AIDS-free generation, where the number of new infections<br />

is less than the number of people who are put on therapy.<br />

The strategic vision for tackling emerging and reemerging<br />

infectious diseases involves developing platforms of vaccines<br />

and drugs that would have universal applicability, rather than<br />

trying to chase everything that might emerge. With regard<br />

to immunology, it’s just fundamentally good, sound basic<br />

research to understand the mechanisms of immune function<br />

to properly understand how we might suppress aberrant<br />

mechanisms and enhance deficient mechanisms.<br />

8<br />

www.businessofgovernment.org<br />

The Business of Government

Conversations with Leaders<br />

It’s becoming quite evident that we live in a “global community”<br />

[with] certain consequences. The idea that we worry<br />

about certain diseases and there are diseases other people<br />

worry about is antiquated.<br />

On Challenges Facing NIAID<br />

We live in an era of constrained resources [and unprecedented]<br />

scientific opportunities. This is a real challenge:<br />

how do you get the best bang for the buck? How do we<br />

pursue groundbreaking research that will ultimately benefit<br />

public health under tight budgets? We meet this challenge<br />

by prioritization, which is essential because there are a lot<br />

of good ideas, but in an era of fiscal constraint you can’t<br />

pursue them all.<br />

The next significant challenge we face is particular to<br />

NIAID’s unique mission—anticipating the unexpected! Most<br />

institutes at NIH, including NIAID, are responsible for the<br />

basic and clinical research in a particular area, whether it’s<br />

focusing on heart, lung, blood, kidney, etc. For us, it’s infectious<br />

diseases and immunology. In addition to that predictable<br />

translation from a basic concept to an applied clinical<br />

concept, NIAID must also always be ready for the unexpected.<br />

At a moment’s notice we may need to respond to a<br />

completely new infection.<br />

This is exactly what we faced in the summer of 1981. At<br />

that time, the CDC’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report<br />

reported the first five cases of pneumocystis pneumonia in<br />

gay men from Los Angeles. One month later, an additional<br />

26 young gay men from New York, San Francisco, and LA<br />

presented with this strange disease. Immediately, it was our<br />

task to figure what it was and what can be done. This need<br />

to deal with the unexpected and unpredictable presents a<br />

unique challenge for NIAID. It isn’t every week that a new<br />

cancer is discovered or a new form of heart disease, but at<br />

any given time we could face a brand new infectious disease.<br />

On the Characteristics of Infectious Diseases<br />

Infectious diseases have a number of unique characteristics.<br />

Microbes have the capability, through mutations, of changing<br />

characteristics in minutes to days because of their replication<br />

capability. Microbes like HIV replicate thousands of<br />

times per day. When you’re talking about infectious diseases,<br />

it’s a constant evolution. You have a disease. It spreads. You<br />

develop a drug. You treat a person, and then all of a sudden<br />

after a period of years, the virus or the bacteria develops<br />

resistance and you have to come in with another drug. It’s<br />

a constant, dynamic, emerging world of microbes that we’ll<br />

never completely wipe out; microbes constantly adapt for<br />

their own survival. We need to stay a step ahead of it all with<br />

our intervention, therapies, vaccines, or diagnostics.<br />

It’s a constant state of surprise given the extraordinary capability<br />

of microbes, viruses, bacteria, and parasites to evolve,<br />

emerge newly, or reemerge in a different setting and under<br />

different circumstances. I gave the example of HIV/AIDS<br />

emerging in 1981 as a truly new infection. In addition, we<br />

also face reemerging infections; these are infections that have<br />

historically existed that may be dominant, but reemerge either<br />

in a different form or a different location. For example, we<br />

have drug-resistant malaria. For years, we were able to treat<br />

malaria easily, and then drug-resistant forms emerged. We<br />

have diseases that have been around a long time, but not in<br />

our backyard. A classic example of that is West Nile Virus,<br />

which was in the Middle East and in Africa for centuries, but<br />

only within the last couple of decades has come to the U.S.<br />

It’s not so much a state of surprise, but [a] constant state of<br />

the unexpected.<br />

On the Pursuit of Progress: HIV/AIDS<br />

HIV<br />

In the mid-80s and early 90s, the median survival of my<br />

patients with HIV/AIDS was six to eight months, meaning<br />

SPRING 2014 IBM Center for The Business of Government 9

Conversations with Leaders<br />

that 50 percent of the patients would be dead in six to eight<br />

months, which is horrible. By applying fundamental basic<br />

research that involves understanding the replication cycle,<br />

targeting the vulnerable components of that replication<br />

cycle, and designing a drug therapy … fast-forward 30 years<br />

[to] today, we now have more than 30 FDA-approved antiretroviral<br />

drugs. When we use these drugs in combination, a<br />

recently infected person could [possibly] live an additional<br />

50 years. That’s a dramatic turnaround over a 30-year period.<br />

Along with these anti-retroviral drugs, we have effective lowtech<br />

forms of prevention.<br />

In addition, we’re actively pursuing the development of an<br />

HIV vaccine. The question is, can we cure people? Can we<br />

get to the point where you suppress the virus enough that<br />

you could stop the drug and the virus won’t rebound? I don’t<br />

know … but it’s certainly … worth trying …. Over the last<br />

three years, the advance … toward a vaccine is much more<br />

than what we had seen in the previous 15 to 20 years.<br />

On Bringing Tuberculosis (TB) Research into the<br />

21st Century<br />

Tuberculosis<br />

Tuberculosis is one of these enduring global health issues.<br />

It has been neglected because of a good dose of complacency—that<br />

it’s somebody else’s problem, not a problem for<br />

the developed world. One-third of the world’s population<br />

is infected with latent tuberculosis. That’s over two billion<br />

people. Though they’re not sick, they have latent TB, with<br />

about eight million new cases a year and about 1.3 million<br />

deaths per year.<br />

Our goal is to bring the science of tuberculosis into the 21st<br />

century. Until recently, we haven’t had a new drug for tuberculosis<br />

in over 40 years. Just this past year, we had the first<br />

drug that was specifically approved only for TB.<br />

We have a very ineffective tuberculosis vaccine. We have<br />

diagnostics that are antiquated. We don’t have enough drugs<br />

and the drugs we do have require six months to a year to<br />

suppress the disease. We need to play serious catch-up.<br />

We’re doing that by aggressively applying modern techniques<br />

such as the ability to rapidly sequence strains of TB, identify<br />

vulnerable parts of the microbacteria susceptible to drugs,<br />

and code for antigens that might be used for a vaccine. We<br />

have ways of not only diagnosing TB, but also determining<br />

at the point of care whether we’re dealing with a resistant<br />

tuberculosis.<br />

About 10 percent of the two billion-plus who are latently<br />

infected with TB will, during their lifetime, manifest active<br />

TB. We don’t understand this mechanism. We don’t understand<br />

the fundamental pathogenesis of tuberculosis or the<br />

systems biology of the immune system. Why doesn’t the<br />

immune system completely eradicate tuberculosis? Why<br />

do you always have a little bit that remains and is latent?<br />

What is the proper immune response to protect you? We<br />

are applying microbial genomic sequencing technologies,<br />

investing in the basic science underlying point-of-care<br />

diagnostics, supporting research to develop vaccine candidates,<br />

and engaging in public-private partnerships for drug<br />

development.<br />

On the Development of a Universal Influenza<br />

Vaccine<br />

We have made significant progress toward the production<br />

of vaccines, but for me and my colleagues in the field, the<br />

real goal is to develop what we call a universal influenza<br />

vaccine. This would obviate the need for annual influenza<br />

vaccination and enhance our ability to respond to … influenza<br />

pandemics. A universal flu vaccine induces a response<br />

against that component of the influenza virus that doesn’t<br />

change or changes very little from season to season. We are<br />

getting closer to this goal, so the exciting thing in influenza<br />

research is to develop a truly effective influenza vaccine that<br />

you may need to give once or two or three times throughout<br />

the lifetime to protect you against all strains.<br />

On Combating Drug Resistance<br />

Influenza<br />

MRSA<br />

It is a fact of life that microbes, given their replicative and<br />

mutational capability, adapt to whatever you throw at them.<br />

When you treat a patient with an antibiotic or an antiviral,<br />

10<br />

www.businessofgovernment.org<br />

The Business of Government

“It’s a constant state of surprise given the extraordinary capability of microbes,<br />

virus, bacteria, and parasites to evolve, emerge newly, or reemerge in a<br />

different setting and under different circumstances.”<br />

unless you completely eliminate that bacteria or that virus,<br />

it will naturally select for the mutation that is resistant to<br />

getting killed. When you are infected with a virus or bacteria<br />

it isn’t a single homogenous microbe. Mutations occur that<br />

can make a microbe resistant. If you inadequately treat<br />

the sensitive microbes, resistant ones might emerge and<br />

dominate.<br />

Therefore … if you use antibiotics when you don’t need them<br />

or use them at the incorrect dose, you will inadvertently<br />

select for resistant microbes. The overuse and inappropriate<br />

use of antibiotics is a surefire way to help the microbe select<br />

for resistance, leading to drug-resistant forms.<br />

In an outbreak of a disease, using sequencing and computational<br />

biology, we can very rapidly know whether we are<br />

dealing with a microbe, for example a virus. We can then<br />

identify the class of virus: checking databases, we assess<br />

whether there is a virus that absolutely matches it. If this<br />

virus doesn’t match anything we’ve seen before, then wow,<br />

we’re dealing with a brand-new virus. Once you identify<br />

it and sequence it, you can actually create it and then<br />

On Technological Advancement and the Use of<br />

Scientific Technology<br />

From the standpoint of infectious diseases, there are a<br />

number of technologies, but let me pick out one that is<br />

really transformative. It is the ability to rapidly sequence the<br />

genome of the microbes. To give you a sense of the transformation,<br />

when the first microbe was sequenced decades ago<br />

it took about a year and about $40 million. Today, we can<br />

do it in a few hours for a couple of dollars. It’s just breathtaking<br />

what you can do. We refer to it as next generation<br />

sequencing, NGS, or deep sequencing where you could take<br />

a quasi-species of viruses and sequence every single one<br />

of them and know the signatures of resistance, transmissibility,<br />

and pathogenesis. This is the application of genomics,<br />

proteomics, and informatics. These are technically the most<br />

transforming advances that we’ve been able to make.<br />

From a basic research perspective, we are able to better<br />

understand how the microbe works—all the genetic determinants<br />

of its functions. You arrive at a genotype and a phenotype.<br />

Genotype is what the genes are and the phenotype<br />

is how the microbe acts, what it does. To be able to make<br />

that correlation between genotype and phenotype instantaneously,<br />

as opposed to waiting, is phenomenal. From an<br />

applied research standpoint, the progress is breathtaking.<br />

SPRING 2014 IBM Center for The Business of Government 11

Conversations with Leaders<br />

“ The strategic vision for tackling<br />

emerging and reemerging<br />

infectious diseases involves<br />

developing platforms of vaccines<br />

and drugs that would have<br />

universal applicability, rather than<br />

trying to chase after everything<br />

that might emerge.”<br />

12<br />

www.businessofgovernment.org<br />

The Business of Government

Conversations with Leaders<br />

manipulate it. This enables you to target drugs against it.<br />

These are activities that can be done today almost instantaneously,<br />

which years ago took months, if not a year or<br />

longer.<br />

On the Evolving Strategies in Biodefense<br />

Our biodefense strategy has evolved since the mid-2000s,<br />

[when] we were developing vaccines and drugs for threats<br />

we knew. It became clear that it was futile to try and make<br />

an intervention against each and every single potential<br />

microbe. We started to focus on what we call broad multiuse<br />

platforms for vaccines, antibiotics, and antivirals. We<br />

could have an antiviral that would be effective against<br />

multiple different classes of viruses.<br />

This shift in strategies has been transformative for the entire<br />

field of microbiology. It allows us to develop sustainable<br />

interventions against microbes that someone might deliberately<br />

release, namely bioterrorism. It also helps us prepare<br />

against the more likely scenario and that is nature itself.<br />

The evolutions of microbes that have devastated civilizations<br />

are naturally occurring events. In the quest to protect<br />

and develop interventions against deliberately released<br />

microbes, we’ve come a long way to enhance our capability<br />

of responding to naturally occurring events.<br />

On the Future<br />

We can expect extraordinary, breathtaking opportunities<br />

in science. From the standpoint of infectious diseases and<br />

immunology, it is being able to unlock the intricacies and<br />

the secrets of the immune system. How might we control<br />

it when it’s aberrant and supplement it when it’s deficient?<br />

With regard to microbes, we remain ever vigilant for any<br />

emerging infectious disease. We also seek, beyond just an<br />

aspiration, to send HIV/AIDS, malaria, and tuberculosis the<br />

way of smallpox. We pursue these goals, and our mission,<br />

in an era of constrained resources at a time when some<br />

view scientific research as a discretionary component of the<br />

federal budget. Personally, I don’t think science should be a<br />

discretionary component. It should be a mandatory component<br />

of what we do. ¥<br />

To learn more about the National Institute of Allergy and<br />

Infectious Diseases, go to www.niaid.nih.gov/Pages/default.aspx.<br />

To hear The Business of Government Hour’s interview with Dr. Anthony<br />

Fauci, go to the Center’s website at www.businessofgovernment.org.<br />

To download the show as a podcast on your computer or MP3 player,<br />

from the Center’s website at www.businessofgovernment.org, right<br />

click on an audio segment, select Save Target As, and save the file.<br />

To read the full transcript of The Business of Government Hour’s<br />

interview with Dr. Anthony Fauci, visit the Center’s website at<br />

www.businessofgovernment.org.<br />

SPRING 2014 IBM Center for The Business of Government 13

Conversations with Leaders<br />

A Conversation with J. Christopher Mihm<br />

Managing Director, Strategic Issues<br />

Government Accountability Office<br />

Governments today face serious public management challenges<br />

that go to the core of effective governance and leadership,<br />

testing the very form, structure, and capacity required<br />

to meet these challenges head on. These challenges run the<br />

gamut—national security, the aging population, mounting<br />

fiscal pressures, and a host of others. Given these challenges,<br />

government leaders need to reassess and reprioritize<br />

how they do business. For these leaders it is ultimately about<br />

delivering meaningful results and being solid stewards of the<br />

public trust.<br />

In many ways the U.S. Government Accountability Office<br />

(GAO) provides the oversight, the insight and the foresight<br />

that can assist today’s government leaders to better manage<br />

resources, enhance program performance, and forge a path<br />

to a more sustainable future. What are the fiscal, management<br />

and performance challenges facing today’s government<br />

executive? What is the goal of GAO’s High Risk Series? How<br />

are performance data being used to drive decisions in the<br />

federal government? How can agencies change the way they<br />

do business to respond effectively to 21st century governance<br />

challenges?<br />

Chris Mihm, GAO’s Managing Director for Strategic Issues,<br />

joined me on The Business of Government Hour to explore<br />

these questions and more. The following provides an edited<br />

excerpt from our interview. – Michael J. Keegan<br />

On the History and Mission of GAO<br />

The General Accounting Office was formed in 1921. In 2004,<br />

it was renamed the Government Accountability Office to<br />

more accurately reflect the work we do today. Our mission<br />

is to support the U.S. Congress in meeting its constitutional<br />

responsibilities. We are a congressional agency that focuses<br />

on helping to improve the performance and ensure the<br />

accountability of the American government for the benefit of<br />

the American people. In recent years, we have done between<br />

800 and 900 products a year. Most of those are performance<br />

audits with probably 90% performed at the request of<br />

Congress or written into legislation.<br />

Our audit work falls into three broad areas—oversight,<br />

insight, and foresight. Our oversight mission focuses on<br />

compliance and making sure that funds are properly<br />

expended for their intended purposes. Our work also offers<br />

insights into what works, identifying best practices that can<br />

be leveraged and adopted, where appropriate, across government.<br />

Finally, what we call foresight involves pinpointing<br />

emerging trends, making Congress aware of them, and<br />

informing them of the possible implications of these trends<br />

for public policy and governance.<br />

We pursue our mission with an approximate budget of $546<br />

million a year. Like most other federal agencies, we have had<br />

a decline during the [recent] period of austerity. Our staffing<br />

is at about 2,900 today, which is among the lowest since the<br />

1930s. We’re organized here in Washington, D.C., with 11<br />

field offices across the country. About 70% of the GAO staff<br />

is located in D.C.<br />

14<br />

www.businessofgovernment.org<br />

The Business of Government

Conversations with Leaders<br />

On Leading GAO’s Strategic Issues Portfolio<br />

There are 14 teams within GAO. For the most part, these<br />

teams are programmatically organized. For example, we<br />

have a team that focuses on defense issues, another on<br />

natural resources, and still another that concerns itself with<br />

the physical infrastructure of the U.S. However, some of<br />

the teams are crosscutting in nature. The team that I lead,<br />

Strategic Issues, is one of the crosscutting teams. Our focus<br />

is more functional and less programmatic. We look at functional<br />

issues that span across government and programs.<br />

GAO’s Strategic Issues team supports the agency’s third strategic<br />

goal, which is to help transform the federal government<br />

to address national challenges. We have responsibility<br />

for a broad set of crosscutting governance issues encompassing<br />

performance planning, strategic planning, regulatory<br />

policy, and strategic human capital management. We’re<br />

also concerned with how the government funds itself, which<br />

entails looking at the tax system in terms of tax policy,<br />

administration, as well as budgeting. We perform our own<br />

engagements—audits that typically culminate in reports. Just<br />

as importantly, we work with and support our colleagues<br />

from other teams within GAO. For example, if the GAO<br />

Defense Group perhaps identifies a human capital issue,<br />

then we are there to provide them the latest thinking and<br />

best practices to address this issue.<br />

On Challenges and Changes<br />

We work in a very challenging environment. We face what<br />

I refer to as a supply-demand imbalance. Congress’ need<br />

for independent, objective, and timely information, as well<br />

as assessments on how to improve government performance,<br />

has grown markedly and continues to grow. At the<br />

same time, our budget has been going down. This situation<br />

requires us to work very closely with our clients to understand<br />

their needs and set clear expectations. The only thing<br />

worse than bad news is bad news that comes late or bad<br />

news that is unexpected.<br />

I also want our auditing techniques to be top-tier, and that<br />

the questions we’re asking are suited to the problems we’re<br />

addressing. For example, when we do a performance audit<br />

of a government program, these audits have followed a traditional<br />

logic model approach. We would assess a program’s<br />

inputs (e.g., resources expended) and outputs (e.g., products<br />

produced) and determine its effectiveness. Increasingly,<br />

the focus is shifting away from program outputs and more<br />

towards outcomes. This approach changes the unit analysis,<br />

given we are now concerned with an outcome and working<br />

back, which is a distinctly different approach than the typical<br />

logical model that starts with a program and works through<br />

its specific inputs, activities, and outputs.<br />

Given that government is confronting increasingly complex,<br />

wicked challenges, this shift in focus toward outcomes and<br />

results may present a more suitable approach to effective<br />

governance. It also rests on the recognition that the outcomes<br />

being sought today are not going to be possible by one organization<br />

using one program strategy, operating on its own.<br />

They are going to be achieved by a variety of programs<br />

working together in a coordinated way to achieve results. This<br />

notion of complexity and network management is certainly a<br />

big change requiring a new way of doing business.<br />

The pace at which decision-makers need and must have<br />

information has changed significantly. Where we used to<br />

have time to pilot-test something or shake out the bugs,<br />

today the impetus has changed. Technology and social media<br />

have really pushed this change.<br />

On the Importance of GAO’s High Risk Series<br />

In 1990, GAO began a program to report on government<br />

operations that it identified as high risk. The High Risk Series<br />

was designed to highlight major program areas that are most<br />

vulnerable to waste, fraud, abuse, mismanagement or in<br />

need of broad-based transformation. Since then, GAO has<br />

reported on the progress to address high-risk areas. In our<br />

last report, two areas were removed from the high-risk designation:<br />

management of interagency contracting and IRS business<br />

systems modernization. Two areas were added: limiting<br />

SPRING 2014 IBM Center for The Business of Government 15

Conversations with Leaders<br />

LOGIC MODELS<br />

OUTCOMES<br />

OUTPUTS<br />

ACTIVITIES<br />

INPUTS<br />

Long term|Intermediate|Short<br />

Benefits or changes for<br />

participants during or<br />

after program activities<br />

The direct<br />

products of<br />

program<br />

activities<br />

What the<br />

program does<br />

with inputs<br />

to fulfill its<br />

mission<br />

Resources<br />

dedicated to<br />

or consumed<br />

by the<br />

program<br />

INPUTS<br />

OUTPUTS<br />

ACTIVITIES<br />

OUTCOMES<br />

Resources<br />

dedicated to<br />

or consumed<br />

by the<br />

program<br />

The direct<br />

products of<br />

program<br />

activities<br />

What the<br />

program does<br />

with inputs<br />

to fulfill its<br />

mission<br />

Short|Intermediate|Long term<br />

Benefits or changes for<br />

participants during or<br />

after program activities<br />

Logic models can strengthen the development of program outcomes, validate underlying program logic, and explain the purpose and operation of the program to<br />

others. Logic model is one among a number of planning and evaluation tools that provide a structured approach to clarifying activities and intended outcomes.<br />

When used as planning tool, the logic model “starts with the end” in mind by focusing on desired outcomes. It then requires the identification of outputs that contribute<br />

to those outcomes, activities that produce those outputs, and the inputs necessary to achieve these outcomes.<br />

When used as an evaluative tool, it starts with inputs working through desired outcomes; it identifies measures that will be used to determine whether desired outcomes<br />

have been achieved as well as the sources of data required to support the measurement of those outcomes.<br />

the federal government’s fiscal exposure by better managing<br />

climate change risks and mitigating gaps in weather satellite<br />

data. These changes bring GAO’s 2013 High Risk List<br />

to a total of 30 areas. Overall, GAO’s high risk program has<br />

served to identify and help resolve serious weaknesses in<br />

areas that involve substantial resources and provide critical<br />

services to the public.<br />

Our next report is scheduled for release in February 2015<br />

inclusive of updates, additional [high risk areas], and<br />

hopefully removals. We do that because it helps shape the<br />

congressional oversight agenda. As Justice Brandeis said,<br />

sunshine is the best disinfectant. Since the high-risk program<br />

began, the government has taken high-risk problems seriously<br />

and has made long-needed progress toward correcting them.<br />

On the Promises of the GPRA Modernization Act<br />

of 2010<br />

One of the greatest accomplishments of the original GPRA<br />

Act of 1993 was putting in place a performance infrastructure<br />

that required agencies to do strategic plans, annual<br />

performance plans, performance reporting with focus<br />

outcomes, and performance measures. It was lacking in two<br />

very important areas. The original GPRA was unsuccessful in<br />

getting agencies to work effectively on specific issues across<br />

organizational boundaries. It also generated volumes of<br />

performance information that was available but rarely being<br />

used to inform decision-making.<br />

The GPRA Modernization Act of 2010 was designed to<br />

address these two limitations and more. It sought to craft a<br />

16<br />

www.businessofgovernment.org<br />

The Business of Government

“Our audit work falls into three broad areas—oversight, insight, and foresight. Our<br />

oversight mission focuses on compliance and making sure that funds are properly<br />

expended for their intended purposes. Our work also offers insights into what works,<br />

identifying best practices that can be leveraged and adopted, where appropriate,<br />

across government. Finally, what we call foresight involves pinpointing emerging<br />

trends, making Congress aware of them, and informing them of the possible<br />

implications of those trends for public policy and governance.”<br />

more integrated and crosscutting approach to federal performance<br />

and push for the expanded use of performance<br />

information. This law established a variety of requirements<br />

and mechanisms to make this happen (i.e., the establishment<br />

of agency priority goals and cross-agency priority goals).<br />

Under the GPRA Modernization Act, we have a statutory<br />

responsibility to do periodic reviews of its implementation<br />

among federal agencies. GAO issued its latest report in June<br />

2013 and found that agencies had been pretty successful<br />

designating the number two in the agency or the deputies to<br />

be the chief operating officers. There are chief performance<br />

officers within agencies and goal leaders that have been<br />

designated as well. Putting this infrastructure in place is a<br />

positive and important development.<br />

The report did identify weaknesses: agencies need to ensure<br />

that performance information is useful and being used by<br />

federal managers to improve results, they need to pursue<br />

additional opportunities to address crosscutting issues,<br />

present performance information that could better meet<br />

users’ needs, and provide performance information that is<br />

useful to congressional decision-making. We’ve made progress,<br />

but we need to keep pushing this crosscutting issue with<br />

agencies and OMB. It’s key in realizing greater effectiveness<br />

and cost savings.<br />

GAO Featured Reports<br />

Duplication & Cost Savings:<br />

GAO’s yearly report on areas where<br />

the federal government could reduce<br />

duplication and achieve cost savings.<br />

High Risk Series:<br />

GAO’s list of programs that need<br />

continued attention due to high risk<br />

factors.<br />

Managing for Results in Government:<br />

Effective performance management<br />

helps the federal government to<br />

improve outcomes in areas that affect<br />

nearly every aspect of Americans’ lives,<br />

from education, health care, and housing<br />

to national and homeland security.<br />

SPRING 2014 IBM Center for The Business of Government 17

Conversations with Leaders<br />

“ GAO’s Strategic Issues team<br />

supports the agency’s third<br />

strategic goal, which is to help<br />

transform the federal government<br />

to address national challenges.<br />

We have responsibility for a broad<br />

set of crosscutting governance<br />

issues encompassing performance<br />

planning, strategic planning,<br />

regulatory policy, and strategic<br />

human capital management across<br />

the federal government.”<br />

18<br />

www.businessofgovernment.org<br />

The Business of Government

Conversations with Leaders<br />

On Opportunities to Reduce Fragmentation,<br />

Overlap, and Duplication<br />

GAO issues an annual report on overlap, duplication, and<br />

fragmentation in government programs. We have identified<br />

over 380 actions that the administration and Congress<br />

can take to address fragmentation, overlap, and duplication.<br />

GAO’s 2013 annual report identifies 31 new areas where<br />

agencies may be able to achieve greater efficiency or effectiveness;<br />

17 involve fragmentation, overlap, or duplication.<br />

The number of program areas where there’s pure overlap—<br />

same programs, same tools, going to the same beneficiary or<br />

target population—is relatively infrequent. Far more frequent<br />

is overlap, which is the same population, but use of different<br />

tools or program strategies. Even more frequent is fragmentation,<br />

which is a variety of different programs using different<br />

strategies that are all trying to achieve a common outcome.<br />

On duplication and overlap, we’ll find success when we<br />

eliminate low-performing or ineffective programs and move<br />

money to better-performing programs that will net better<br />

outcomes. Regarding fragmentation, the solution is very often<br />

getting agencies to work better together; this is absolutely<br />

essential.<br />

We also found other cost savings or revenue enhancement<br />

opportunities. For example, we should do a better job<br />

reducing the net tax gap of $385 billion. The tax gap is the<br />

annual difference between what is legally owed and what<br />

is actually collected by IRS. Over the last few years, my<br />

group has focused on how the IRS can pursue the right mix<br />

of enforcement strategies and citizen service strategies to<br />

reduce that tax gap.<br />

Addressing fragmentation, overlap, and duplication will<br />

require continued attention by the executive branch agencies<br />

and targeted oversight by Congress.<br />

On the Future<br />

The country faces long-term fiscal issues requiring some<br />

fundamental decisions. We support the Congress as it<br />

ponders reprioritization and rethinking to address these fiscal<br />

issues. Since we’re fundamentally interested in improving<br />

performance of government, the way we’re going to do it<br />

is by improving the connections across organizations more<br />

than simply eking out another one or two percent of productivity<br />

out of any individual agency.<br />

I think the Center’s special report, Six Trends Driving Change<br />

in Government, contributes to a better understanding. I<br />

was very pleased to have participated in some of the initial<br />

brainstorming associated with its development. When we’re<br />

looking at drivers such as risk, innovation, mission, performance,<br />

efficiency, and leadership, there are certainly things<br />

individual organizations need to do in each of those areas.<br />

Fundamentally, at the end of the day, to improve the way<br />

organizations work across boundaries, we must recognize<br />

that risk management is more than how I manage my risk in<br />

my four walls. It also includes how my partners, whom I am<br />

absolutely dependent upon, manage their risk; how do we<br />

foster innovation across a network? What does leadership<br />

look like across a network? What does performance look like<br />

across a network? Individual agency improvement efforts are<br />

paying real dividends, but huge improvements are going to<br />

come in working better across organizations.<br />

We’re working on very difficult issues. Given budget realities,<br />

this may require GAO to perform fewer jobs, but the<br />

quality of our work will never be sacrificed; that is nonnegotiable.<br />

Given the speed of the decision-making, we need<br />

to make sure the work we’re doing is sufficient to answer<br />

the questions posed, so that we get the information to the<br />

decision-makers in the time and format they need. A beautiful,<br />

well-crafted report that comes in one day after the decision<br />

was made is essentially an historical document. With<br />

the speed of decision-making, social media, and all the rest,<br />

we need to find ways to radically streamline how we get our<br />

information out. We have an initiative underway in GAO<br />

that’s designed to do just this. ¥<br />

To learn more about the Government Accountability Office,<br />

go to www.gao.gov.<br />

To hear The Business of Government Hour’s interview with J. Christopher<br />

Mihm, go to the Center’s website at www.businessofgovernment.org.<br />

To download the show as a podcast on your computer or MP3 player,<br />

from the Center’s website at www.businessofgovernment.org, right<br />

click on an audio segment, select Save Target As, and save the file.<br />

To read the full transcript of The Business of Government Hour’s<br />

interview with J. Christopher Mihm, visit the Center’s website at<br />

www.businessofgovernment.org.<br />

SPRING 2014 IBM Center for The Business of Government 19

Conversations with Leaders<br />

A Conversation with Vice Admiral Mark Harnitchek<br />

Director, Defense Logistics Agency<br />

The Defense Logistics Agency (DLA) provides full-spectrum<br />

logistical support to soldiers, sailors, airmen, Marines, and<br />

civilians around the world every day and for every major<br />

conflict over the past five decades. Logistics is a cost driver<br />

that must be managed with deliberate precision. DLA’s readiness<br />

to respond to warfighter needs is built on an integrated<br />

supply chain that must be efficient and effective. As stewards<br />

of the Department of Defense’s resources, the agency must<br />

go beyond simply responding to demands to more effectively<br />

anticipating them.<br />

Over the next decade, DLA will find its comprehensive logistics<br />

services needed more than ever in new and challenging<br />

ways. The very nature of envisioned threats and conflicts,<br />

combined with increased fiscal challenges, demands an agile,<br />

joint logistics response marked by innovation and best practices.<br />

What are DLA’s strategic priorities? How is DLA working<br />

to reduce cost while improving support of the warfighter?<br />

What about DLA’s role in providing humanitarian assistance<br />

and disaster relief support? Vice Admiral Mark Harnitchek,<br />

Director of the Defense Logistics Agency, joined me on The<br />

Business of Government Hour to explore these questions<br />

and more. The following provides an edited excerpt from<br />

our interview. — Michael J. Keegan<br />

On the Mission and Operations of the Defense<br />

Logistics Agency<br />

DLA was established on October 1, 1961, and was known<br />

as the Defense Supply Agency before officially changing<br />

to its present name in 1977. It was conceived in the 1960s<br />

as a more efficient way to provide armed services with<br />

supplies. The agency has evolved over time to provide a full<br />

spectrum of logistics, acquisition and technical services …<br />

sourcing and providing almost every consumable item used<br />

by our military forces worldwide—food, medicines, medical<br />

surgical equipment, fuel, construction equipment, construction<br />

supplies, uniforms, and all the things used in the field.<br />

DLA also supplies more than 84 percent of the military’s<br />

spare parts. In addition, we manage reutilization of military<br />

equipment, provide catalogs and other logistics information<br />

products, and offer document automation and production.<br />

DLA has 27,000 people working across 30 countries and 48<br />

states to meet its mission. We are indeed a global organization.<br />

The primary source of financing is our revolving fund,<br />

the Defense Working Capital Fund. We sell to our service<br />

customers the products and services they need. They reimburse<br />

us and those funds go into our working capital fund—<br />

basically, our activity is financed with the funded orders<br />

placed by our customers.<br />

We are required to keep a certain amount of cash on hand<br />

to pay our bills. We are right around $40 billion in sales and<br />

about $5 billion to $6 billion in cost of operations. Our two<br />

biggest financial lines of operation are the things that we buy<br />

and the cost of our operations, which includes staff, infrastructure,<br />

and transportation.<br />

20<br />

www.businessofgovernment.org<br />

The Business of Government

Conversations with Leaders<br />

Fuel is our largest commodity purchase, equaling about<br />

half of that $40 billion. We’re in the same league as Delta<br />

and Northwest in the amount of fuel we buy. It’s about 130<br />

million barrels a year. Food is another big ticket item, at<br />

around $4 billion to $5 billion. Pharmaceuticals are in the<br />

$4 billion to $5 billion range as well, with uniforms, repair<br />

parts, construction equipment, etc., rounding out the last $10<br />

billion of our purchases.<br />

On the Importance of Understanding our<br />

Customers<br />

I am very focused on understanding my customers’ needs,<br />

requirements, and operational outcomes. We take that as<br />

understanding the array of required products and services<br />

while responding to the needs of our customers and assisting<br />

them to achieve mission outcomes. For example, our support<br />

in Afghanistan is to have the requisite amount of food and<br />

fuel on hand to meet the operational commanders’ needs,<br />

whatever those are, and then have all those other supply<br />

chains positioned to do that.<br />

From a 50,000-foot perspective, it’s not all that difficult. It’s<br />

understanding what it is your customers want, the outcome<br />

you’re trying to achieve, and then figuring out on the back<br />

end how to achieve it in the most efficient and cost-effective<br />

manner. Given our service customers pay us for these goods<br />

U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist 3rd Class Lacordrick Wilson<br />

and services, we’re very focused on getting the best value<br />

for our money and passing that on to our customers. So if<br />

I can sell something for 10 percent less this year than I did<br />

the year before while getting the same operational outcome,<br />

then that’s exactly what we want to do. This is, in a nutshell,<br />

my responsibility and that of the 27,000 military and civilian<br />

folks who work for DLA.<br />

On DLA’s Strategic Vision: “13 in 6”<br />

Since I arrived at DLA, [I have] focused on significantly<br />

improving our performance while dramatically reducing<br />

cost. It is all about putting our customers first, and being a<br />

warfighter-focused, globally responsive, fiscally responsible<br />

supply chain leader.<br />

To make this strategic vision a reality, I introduced my<br />

10-in-5 strategy, which means saving $10 billion over the<br />

next five years by focusing on five core priorities: decrease<br />

direct material costs, decrease operating costs, right-size<br />

inventory, improve customer service, and achieve audit readiness.<br />

But the targets get more aggressive as we go forward.<br />

We’ve upped 10-in-5 to create even more savings; our new<br />

goal [is to] slash $13 billion in operating and material costs<br />

over the next six years. DLA will deliver improved performance<br />

for $13 billion less.<br />

On decreasing direct material costs, we are to be smart<br />

buyers of the right stuff through a combination of reverse<br />

auctions, commercial-type contract terms, substantial<br />

industry partnerships, performance-based logistics and prime<br />

SPRING 2014 IBM Center for The Business of Government 21

Conversations with Leaders<br />

vendor contracts, and significantly reduced lead times. We<br />

are reducing operating costs through a combination of eliminating,<br />

consolidating, and co-locating infrastructure, optimizing<br />

the global distribution network, enhancing retail<br />

industrial support, incorporating process improvements, and<br />

going green at DLA operating locations.<br />

An integral aspect of achieving the 13-in-6 strategy centers<br />

on cleaning out the attic. This involves right-sizing both<br />

war reserves and operational inventory by reviewing and<br />

adjusting strategic requirements, leveraging commercial<br />

supply chains without redundancy, and improving planning<br />

and forecasting accuracy. Our short-term goal is to reduce<br />

excess inventory by $6 billion by the end of 2014 without<br />

sacrificing military readiness.<br />

In the end, our customers must be front and center, so<br />

improving customer service is a key strategic objective. As<br />

with all DoD components, we need to make sure our organization<br />

achieves audit readiness, demonstrating our commitment<br />

to transparency and accountability through our culture<br />

of judiciousness.<br />

On improving performance, you have to give everybody<br />

a target and then you have to fully empower them to start<br />

improving performance and dramatically reducing cost.<br />

This is not something we define; it’s something our service<br />

customers define. Improving performance is not all that difficult<br />

if you stick to the basics. We are an acquisition machine.<br />

You have to buy enough. You have to buy it on time, and<br />

then you have to make sure it gets where it needs to go.<br />

On Reducing Costs Using Reverse Auctions<br />

DLA has substantially increased its reverse auction opportunities,<br />

which has led to savings of more than $1.6 billion. To<br />

put a fine point on it, our energy area achieved $400 million<br />

in savings in fiscal year 2013 by using reverse auctions<br />

to get better prices and increase competition in awarding<br />

fuel contracts. We had another contract that we ran as an<br />

auction for a medical prime vendor for medical supplies. It’s<br />

a 10-year contract worth about $10 billion. We saved five<br />

percent. Five percent of $10 billion is a big number leading<br />

to significant savings. So how do they work?<br />

Instead of a sealed bid or a best and final that we negotiate<br />

with each of the suppliers, reverse auctions run online<br />

and the reverse auction pricing tool should be used for all<br />

competitive purchases over $150,000. Reverse auctions<br />

involve contractors placing a bid lower than an earlier bid,<br />

which fosters intense competition and drives down prices.<br />

Typically, the bidding process lasts about an hour and<br />

auctions are held almost daily by DLA units.<br />

On Right-Sizing Infrastructure and Achieving<br />

Optimization<br />

We manage 26 distribution centers worldwide. To achieve<br />

our 13-in-6 vision, it is important to optimize warehouse<br />

operations and reduce distribution infrastructure. Since we<br />

need to decrease operating costs, we’re going to keep the<br />

inventory we need and store it in our most cost-effective,<br />

advantageously located distribution centers.<br />

Last year, 40 percent of DLA’s inventory was in more than<br />

one place. If you talk to FedEx, they’ll tell you they can<br />