Download this issue as a PDF - Columbia College - Columbia ...

Download this issue as a PDF - Columbia College - Columbia ...

Download this issue as a PDF - Columbia College - Columbia ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

GOOD CHEMISTRY<br />

COLUMBIA COLLEGE TODAY<br />

COLUMBIA COLLEGE TODAY<br />

GOOD CHEMISTRY<br />

ing students more directly <strong>as</strong> in financial aid. That’s a tough position<br />

to put faculty in. And that’s why I argued that the financial sourcing<br />

of financial aid should be matched to the social responsibility — it’s<br />

an institutional responsibility.<br />

You mentioned the restructuring that involved the Faculty<br />

of Arts and Sciences. Let’s turn to that relationship, which is<br />

a complex one but an important one for the <strong>College</strong>. Can you<br />

describe the relationship, and how it might change with your<br />

being part of the new three-person Arts and Sciences executive<br />

committee?<br />

The Faculty of Arts and Sciences w<strong>as</strong> created about the time I came<br />

to <strong>Columbia</strong>. It’s kind of an odd structure, and I use the word<br />

“odd” carefully. We have a collection of schools [<strong>Columbia</strong> <strong>College</strong>,<br />

the School of General Studies, the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences,<br />

the School of the Arts and the School of Continuing Education]<br />

that have students and deans but no specific faculty, and then<br />

we have <strong>this</strong> body called the Faculty of Arts and Sciences, which<br />

contains all the faculty but no students. It’s kind of a curious thing.<br />

This kind of separation between schools and faculty, organizationally,<br />

suggests difference and separation that functionally doesn’t<br />

really exist. I mean, if people go into a cl<strong>as</strong>sroom and teach, you<br />

don’t really think about<br />

whether the students are<br />

in the <strong>College</strong> or General<br />

Studies or wherever. You’re<br />

a faculty member teaching<br />

a bunch of students and developing<br />

a faculty-student<br />

relationship. The fact that<br />

<strong>as</strong> a faculty member you<br />

are a member of the Faculty<br />

of Arts and Sciences, while<br />

the students are enrolled in<br />

a school and not enrolled in<br />

the Faculty of Arts and Sciences,<br />

doesn’t really come<br />

into play. It only comes into<br />

play when you talk about<br />

how you make decisions; it’s an administrative dichotomy that<br />

is not really a functional dichotomy.<br />

And the deans of all the schools have reported to the vice president<br />

[of Arts and Sciences]; that’s what it says in the statutes of<br />

the University. That h<strong>as</strong> certain complications. It inevitably leads<br />

to certain kinds of differences of opinion about what should be<br />

done and how things should be done, because there are different<br />

representations. The vice president represents a different set of interests<br />

from the deans of schools, so there are always going to be<br />

disagreements about what should be done. The structure didn’t<br />

allow for the most effective way to make decisions. So now we’ve<br />

created an Executive Committee of Arts and Sciences, which consists<br />

of the Dean of the Graduate School, the Dean of <strong>Columbia</strong><br />

<strong>College</strong>, who is also the Vice President for Undergraduate Education,<br />

and the Vice President of Arts and Sciences, who also is<br />

the Dean of the Faculty. In my view, that’s a much better way to<br />

make decisions because it combines representation of the three<br />

major constituencies in our enterprise. We have faculty interests,<br />

graduate student interests and undergraduate student interests<br />

— they’re not in opposition, but they’re not identical. So you put<br />

them all together and that group of three people h<strong>as</strong> to come<br />

up with decisions about how to deploy resources, about faculty<br />

appointments, capital projects, budgets, development efforts —<br />

Students learn <strong>as</strong> much or<br />

more from one another <strong>as</strong><br />

they do from professors.<br />

You don’t want everyone<br />

in the <strong>College</strong> to be alike.<br />

You learn by being around<br />

people who have different<br />

points of view, different<br />

life experiences.<br />

all the major things that you need to decide are now made by a<br />

group of people who can effectively represent all the points of<br />

view of all constituencies who make up <strong>this</strong> part of the University.<br />

That’s a much more effective way of making decisions.<br />

It’s been functioning since mid-April, so we don’t know exactly<br />

how it will work out, but so far it’s worked out pretty well.<br />

It might be transitional, it might l<strong>as</strong>t only a short time or it might<br />

l<strong>as</strong>t well beyond my tenure <strong>as</strong> dean. Something else will replace<br />

it someday, something else always does. But I think <strong>this</strong> is much<br />

better than what we had.<br />

It always struck me <strong>as</strong> odd that the Dean of the <strong>College</strong> couldn’t<br />

hire a teacher in the <strong>College</strong> …<br />

Yes, it is odd, isn’t it [laughing]? Well, we started out with a college<br />

and then we added these other schools, and each of them<br />

had a faculty. Functionally, faculty were teaching different students<br />

but had an appointment in one school. That w<strong>as</strong> kind of<br />

awkward, so we created <strong>this</strong> one overall faculty. And that w<strong>as</strong><br />

awkward, too. There were dichotomies that were artificial and<br />

we tried to correct those by having something else that’s slightly<br />

artificial. But you’re gradually trying to remove artificialities. I<br />

have a 170-year-old house in New Jersey that I’m working on all<br />

the time, trying to make it a more functional house. The challenge<br />

isn’t that it’s 170 years old, it’s that people have added things or<br />

changed things all along that weren’t always done so well, so you<br />

gradually try to go back and make it right. That’s essentially what<br />

we’re trying to do here.<br />

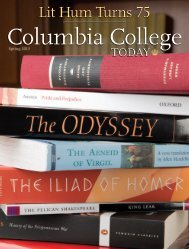

One thing that’s l<strong>as</strong>ted for a while, with changes and additions<br />

along the way, is the Core Curriculum. It’s the <strong>College</strong>’s signature<br />

academic sequence and a bond among alumni. What is<br />

your vision of the place of a core curriculum in a liberal arts<br />

education, and how do you see <strong>Columbia</strong>’s Core evolving?<br />

I’ll answer the l<strong>as</strong>t part first. The Core, with a capital “C,” h<strong>as</strong><br />

existed for almost 100 years but it h<strong>as</strong>n’t existed for all 100<br />

years in exactly the same form. When Contemporary Civilization<br />

started, it used a textbook, written by people at <strong>Columbia</strong>,<br />

which included parts that dealt with industry and agriculture.<br />

Today, we don’t teach anything about industry and agriculture<br />

in Contemporary Civilization, yet everyone views the Core <strong>as</strong> a<br />

permanent part of the <strong>Columbia</strong> educational experience. And it<br />

is. The idea that there is a certain intellectual experience that every<br />

undergraduate is going to have and it’s going to represent a<br />

collection of ide<strong>as</strong> that the faculty feel is really important. That’s<br />

the permanent part.<br />

Exactly what those ide<strong>as</strong> are and what form that takes have<br />

been evolving. I mean, that CC textbook is really interesting. It<br />

is contemporary civilization of 1919; contemporary civilization<br />

of 2012 is a different thing. I think we ought to teach something<br />

about industry and agriculture, but that’s just my view because<br />

students don’t know anything about that and it’s still part of life.<br />

But the curriculum h<strong>as</strong> evolved and it will continue to evolve. We<br />

try things; some don’t work and we replace them. The names get<br />

changed. There w<strong>as</strong> Humanities A and B, <strong>this</strong> became Art Hum<br />

and Music Hum, <strong>this</strong> changed, that changed. There w<strong>as</strong> Major<br />

Cultures and that led to the Global Core, Frontiers of Science w<strong>as</strong><br />

introduced, there w<strong>as</strong> Logic & Rhetoric, now we have University<br />

Writing. Intellectual life moves forward, we learn new things and<br />

new things develop.<br />

The Core, fundamentally, represents a commitment to an idea<br />

that at any one time there is a kind of collective intellectual experience<br />

and a body of knowledge, information, ide<strong>as</strong>, that we want<br />

Professor at heart: Valentini chats with students outside Low Library <strong>this</strong> summer including (top, left to right) Annel Fernandez ’16, Xi<br />

Wang ’16 and Lorenzo Gibson ’16.<br />

PHOTOS: LESLIE JEAN-BART ’76, ’77J<br />

FALL 2012<br />

24<br />

FALL 2012<br />

25