- Page 1 and 2: This content is copyright Flat Worl

- Page 3 and 4: Government Policy End-of-Chapter Ma

- Page 5 and 6: may never take another economics co

- Page 7 and 8: see small groups of people sitting

- Page 9 and 10: CHECKING YOUR UNDERSTANDING 1. List

- Page 11 and 12: you something about how to make bet

- Page 13 and 14: all the different things you like b

- Page 15 and 16: As the game was drawing to a close,

- Page 17 and 18: pollution in Mexico City is in part

- Page 19 and 20: In Conclusion Our book is built aro

- Page 21 and 22: We start with the decision about ho

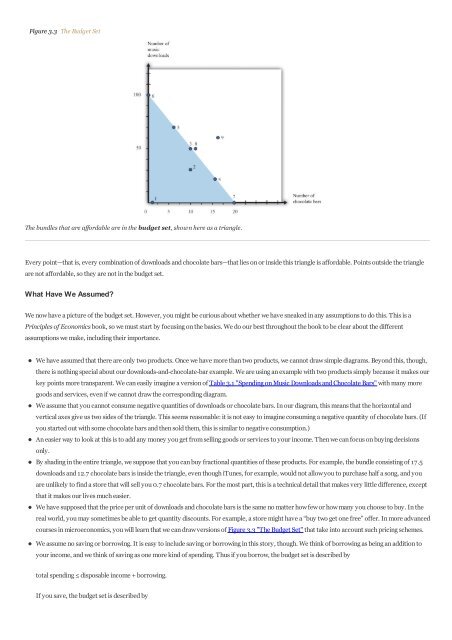

- Page 23: Bundle 6 shows that, if you chose t

- Page 27 and 28: Economists don’t pretend to know

- Page 29 and 30: point. We see what people do, not t

- Page 31 and 32: CHECKING YOUR UNDERSTANDING 1. Supp

- Page 33 and 34: smaller quantity of instant noodles

- Page 35 and 36: Figure 3.9 The Demand Curve Table 3

- Page 37 and 38: example: if the price of CDs increa

- Page 39 and 40: You have a similar decision rule fo

- Page 41 and 42: Figure 3.13 The Valuation of a Car

- Page 43 and 44: CHECKING YOUR UNDERSTANDING 1. Thin

- Page 45 and 46: So Figure 3.14 "The Time Budget Con

- Page 47 and 48: Toolkit: Section 17.3 "The Labor Ma

- Page 49 and 50: CHECKING YOUR UNDERSTANDING 1. If y

- Page 51 and 52: 9. (Advanced) Suppose the governmen

- Page 53 and 54: LEARNING OBJECTIVES 1. What is your

- Page 55 and 56: Figure 4.2 The Budget Line with Two

- Page 57 and 58: The Position of the Budget Line Whe

- Page 59 and 60: Toolkit: Section 17.4 "Choices over

- Page 61 and 62: Saving and Borrowing Your preferred

- Page 63 and 64: Toolkit: Section 17.5 "Discounted P

- Page 65 and 66: Figure 4.8 Individual Loan Supply F

- Page 67 and 68: Similarly, the discounted present v

- Page 69 and 70: are added over one’s lifetime. Se

- Page 71 and 72: years. Cars and kitchen appliances

- Page 73 and 74: Table 4.8 Coin-Flipping Experiment

- Page 75 and 76:

Diversification of Risk In many cas

- Page 77 and 78:

jobs. The unemployment rate is the

- Page 79 and 80:

Figure 4.11 Work Fatalities in the

- Page 81 and 82:

Lottery Games Odds Calculator,” a

- Page 83 and 84:

EXERCISES 1. Explain why an increas

- Page 85 and 86:

Figure 5.1 The eBay Home Page In or

- Page 87 and 88:

Road Map The chapter falls naturall

- Page 89 and 90:

Figure 5.3 The Buyer’s Valuation

- Page 91 and 92:

Figure 5.5 Buyer and Seller Valuati

- Page 93 and 94:

1. The seller knows the buyer’s v

- Page 95 and 96:

You participate as a buyer in an eB

- Page 97 and 98:

transferred from someone who values

- Page 99 and 100:

Double Oral Auctions In a double or

- Page 101 and 102:

Figure 5.11 Obtaining the Market Su

- Page 103 and 104:

Figure 5.13 Supply and Demand When

- Page 105 and 106:

Figure 5.15 Surplus in Equilibrium

- Page 107 and 108:

Inspired by the craigslist posts th

- Page 109 and 110:

Toolkit: Section 17.12 "Production

- Page 111 and 112:

Figure 5.20 Hannah’s Production P

- Page 113 and 114:

Figure 5.22 Julio and Hannah’s Pr

- Page 115 and 116:

frontier has slope −3/2, as Hanna

- Page 117 and 118:

EXERCISES 1. Would you expect to ge

- Page 119 and 120:

6.1 The Goal of a Firm LEARNING OBJ

- Page 121 and 122:

Figure 6.3 The Profits of a Firm We

- Page 123 and 124:

Price ($) Quantity 0 100 2 90 4 80

- Page 125 and 126:

Figure 6.6 The Elasticity of Demand

- Page 127 and 128:

Figure 6.8 Finding the Demand Curve

- Page 129 and 130:

Figure 6.10 Revenues Gained and Los

- Page 131 and 132:

Figure 6.12 Marginal Revenue and De

- Page 133 and 134:

CHECKING YOUR UNDERSTANDING 1. Earl

- Page 135 and 136:

Figure 6.15 An Example of a Cost Fu

- Page 137 and 138:

Figure 6.17 Setting the Price or Se

- Page 139 and 140:

4. If the optimal price is less tha

- Page 141 and 142:

6.5 The Supply Curve of a Competiti

- Page 143 and 144:

Table 6.5 Costs of Production: Incr

- Page 145 and 146:

EXERCISES 1. We suggested that a gr

- Page 147 and 148:

Tigers’ Merchandise Off to Roarin

- Page 149 and 150:

One way to summarize this behavior

- Page 151 and 152:

We typically expect that marginal c

- Page 153 and 154:

Figure 7.5 Market Equilibrium In a

- Page 155 and 156:

Figure 7.6 A Shift in the Supply Cu

- Page 157 and 158:

Comparative Statics The approach th

- Page 159 and 160:

the conclusion that the news should

- Page 161 and 162:

But this is exactly what happens in

- Page 163 and 164:

The example in Table 7.4 "Calculati

- Page 165 and 166:

Figure 7.15 Surplus Away from the M

- Page 167 and 168:

The demand for credit decreases as

- Page 169 and 170:

Toolkit: Section 17.3 "The Labor Ma

- Page 171 and 172:

KEY TAKEAWAYS The supply-and-demand

- Page 173 and 174:

Figure 7.21 An Increase in Marginal

- Page 175 and 176:

KEY TAKEAWAYS Even if markets are n

- Page 177 and 178:

The supply-and-demand framework can

- Page 179 and 180:

Figure 8.2 Walmart: Growing Jobs? S

- Page 181 and 182:

demand in the labor market. In the

- Page 183 and 184:

Figure 8.5 The Technology of a Firm

- Page 185 and 186:

marginal product of labor. In creat

- Page 187 and 188:

Figure 8.8 The Cost Function The co

- Page 189 and 190:

We can see from this equation that

- Page 191 and 192:

Figure 8.12 The Effect of a Change

- Page 193 and 194:

Figure 8.14 The Effect of a Change

- Page 195 and 196:

Production" are based on the follow

- Page 197 and 198:

Suppose you ask this question just

- Page 199 and 200:

Specifically, we can divide entry c

- Page 201 and 202:

to a job offer is very important fo

- Page 203 and 204:

Another source of bargaining power

- Page 205 and 206:

Steven J. Davis, John C. Haltiwange

- Page 207 and 208:

EXERCISES 1. A statistic called “

- Page 209 and 210:

Road Map This chapter begins with a

- Page 211 and 212:

stocks traded in an exchange that s

- Page 213 and 214:

The Foreign Exchange Market Further

- Page 215 and 216:

Toolkit: Section 17.5 "Discounted P

- Page 217 and 218:

Outcome (Number of Oranges) Probabi

- Page 219 and 220:

KEY TAKEAWAYS The value of an asset

- Page 221 and 222:

The supply side is shown in part (a

- Page 223 and 224:

We have also discovered that, in ge

- Page 225 and 226:

There are a couple of possible answ

- Page 227 and 228:

caution: even if markets are not al

- Page 229 and 230:

Figure 9.9 Equilibrium Asset Prices

- Page 231 and 232:

EXERCISES 1. List the factors you t

- Page 233 and 234:

Burger King in Georgia or Arby’s

- Page 235 and 236:

Road Map Because the minimum wage s

- Page 237 and 238:

The first increment of the proposal

- Page 239 and 240:

wage or the real equilibrium quanti

- Page 241 and 242:

Inflation and the Minimum Wage Alth

- Page 243 and 244:

In part (a) of Figure 10.9 "Deadwei

- Page 245 and 246:

Figure 10.11 The Employment Effect

- Page 247 and 248:

To talk about distribution, we need

- Page 249 and 250:

Figure 10.14 Effects of an Increase

- Page 251 and 252:

LEARNING OBJECTIVES 1. How do econo

- Page 253 and 254:

adults.) Figure 10.18 "Teenage Unem

- Page 255 and 256:

economists, particularly because th

- Page 257 and 258:

EXERCISES 1. List three jobs you th

- Page 259 and 260:

some value. In addition, if the mar

- Page 261 and 262:

29, 2007, accessed January 29, 2011

- Page 263 and 264:

Toolkit: Section 17.11 "Efficiency

- Page 265 and 266:

possible to start bringing supplies

- Page 267 and 268:

Suppose you want to purchase a book

- Page 269 and 270:

In part (a) of Figure 11.9 "Tax Inc

- Page 271 and 272:

looked at. Figure 11.12 The Differe

- Page 273 and 274:

Figure 11.13 The Production Possibi

- Page 275 and 276:

Tariffs Where quotas are the equiva

- Page 277 and 278:

unable to migrate, then the equilib

- Page 279 and 280:

“Hiding in the Shadows: The Growt

- Page 281 and 282:

EXERCISES 1. List three additional

- Page 283 and 284:

including taxes on the income peopl

- Page 285 and 286:

Figure 12.2 The Lorenz Curve The mo

- Page 287 and 288:

Table 12.4 "Gini Coefficient over T

- Page 289 and 290:

Measure 1989 Quintile 1994 Quintile

- Page 291 and 292:

KEY TAKEAWAYS The Lorenz curve show

- Page 293 and 294:

skills, but these are much more com

- Page 295 and 296:

Economic forces can mitigate discri

- Page 297 and 298:

CHECKING YOUR UNDERSTANDING 1. Draw

- Page 299 and 300:

Toolkit: Section 17.6 "The Credit M

- Page 301 and 302:

means that the total number of choc

- Page 303 and 304:

Incentives Redistribution is more t

- Page 305 and 306:

Not all transfers are public; some

- Page 307 and 308:

EXERCISES 1. Draw a Lorenz curve fo

- Page 309 and 310:

the Cuyahoga River in Ohio was so p

- Page 311 and 312:

We will get to Mexico City shortly.

- Page 313 and 314:

Social Dilemma Air pollution and se

- Page 315 and 316:

the time of other drivers on the ro

- Page 317 and 318:

associated with production by a fir

- Page 319 and 320:

permits from others. A firm with mo

- Page 321 and 322:

egulators simply need to calculate

- Page 323 and 324:

In 1999, the United Nations held an

- Page 325 and 326:

price of oil will increase. This is

- Page 327 and 328:

I am not at all prepared to dismiss

- Page 329 and 330:

excludable, then a modified version

- Page 331 and 332:

EXERCISES 1. In the example about s

- Page 333 and 334:

Busting Up Monopolies Working for A

- Page 335 and 336:

Figure 14.1 The Competitive Market

- Page 337 and 338:

When a firm is maximizing its profi

- Page 339 and 340:

Standard Oil Trust in 1911.Justia.c

- Page 341 and 342:

A jury trial led to an award of $4.

- Page 343 and 344:

monopoly profits. Notice that a fir

- Page 345 and 346:

current prices. This problem is esp

- Page 347 and 348:

demand curve. If firm A sets a pric

- Page 349 and 350:

Figure 14.7 The Payoffs (Profits) f

- Page 351 and 352:

Figure 14.9 The Demand Curve Facing

- Page 353 and 354:

Figure 14.12 The Markets for Both F

- Page 355 and 356:

authorities are too permissive in a

- Page 357 and 358:

EXERCISES 1. Suppose you have two t

- Page 359 and 360:

One hundred years ago, our knowledg

- Page 361 and 362:

lies further to the left than the s

- Page 363 and 364:

Our diet also affects our probabili

- Page 365 and 366:

jobs are in service occupations. Th

- Page 367 and 368:

Figure 15.4 Payments to Hospitals a

- Page 369 and 370:

Toolkit: Section 17.7 "Expected Val

- Page 371 and 372:

Adverse Selection One complication

- Page 373 and 374:

more than you would if you had to p

- Page 375 and 376:

firms to earn a return on this inve

- Page 377 and 378:

KEY TAKEAWAYS Government interventi

- Page 379 and 380:

EXERCISES 1. Is health insurance a

- Page 381 and 382:

delay the purchase of a new car, ch

- Page 383 and 384:

(There is a subtlety you may be won

- Page 385 and 386:

Figure 16.3 "The Incidence of a Tax

- Page 387 and 388:

Figure 16.4 Idealized Effect of Goo

- Page 389 and 390:

What was the sticker price of the c

- Page 391 and 392:

Pricing is only one of many decisio

- Page 393 and 394:

pattern of trade is quite normal: m

- Page 395 and 396:

didn’t warn you.” When you see

- Page 397 and 398:

United States in 1978 and ultimatel

- Page 399 and 400:

Key Links GM: http://www.gm.com/cor

- Page 401 and 402:

Chapter 17 Microeconomics Toolkit I

- Page 403 and 404:

Figure 17.1 Individual Demand The M

- Page 405 and 406:

Figure 17.2 Labor Market Equilibriu

- Page 407 and 408:

next year” is $100. The value of

- Page 409 and 410:

For example, suppose you are offere

- Page 411 and 412:

Chapter 12 "Superstars" Chapter 16

- Page 413 and 414:

Chapter 15 "A Healthy Economy" 17.1

- Page 415 and 416:

market. Tax incidence is the way in

- Page 417 and 418:

Key Insights The production possibi

- Page 419 and 420:

Figure 17.11 Cost Measures Figure 1

- Page 421 and 422:

Comparative statics is a tool used

- Page 423 and 424:

Key Insights The production functio

- Page 425 and 426:

The Main Uses of This Tool Chapter

- Page 427 and 428:

Key Insights As the exchange rate i

- Page 429:

The concept of correlation is quite